Synergistic Effects of Glass and Flax Fibers Reinforced in Fly Ash Geopolymer Matrix

Highlights

- This study compares fly-ash-based geopolymers reinforced with short glass fibers and flax fibers, as well as hybrid fiber reinforcement, which was not previously studied in the literature.

- Results show that 1 wt% glass fibers effectively enhance compressive performance and matrix densification.

- The fiber addition at the tested dosages does not improve flexural strength.

- Optimizing fiber content/dispersion and interfacial treatment is recommended.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

- A reference sample.

- A geopolymer containing 1% by weight of glass fibers (GFs).

- A geopolymer with 1% by weight of flax fibers (FFs).

- Hybrid geopolymer comprising 0.5% CF and 0.5% FF by weight.

2.2. Methods

2.2.1. X-Ray Diffraction

2.2.2. Compressive and Flexural Strength

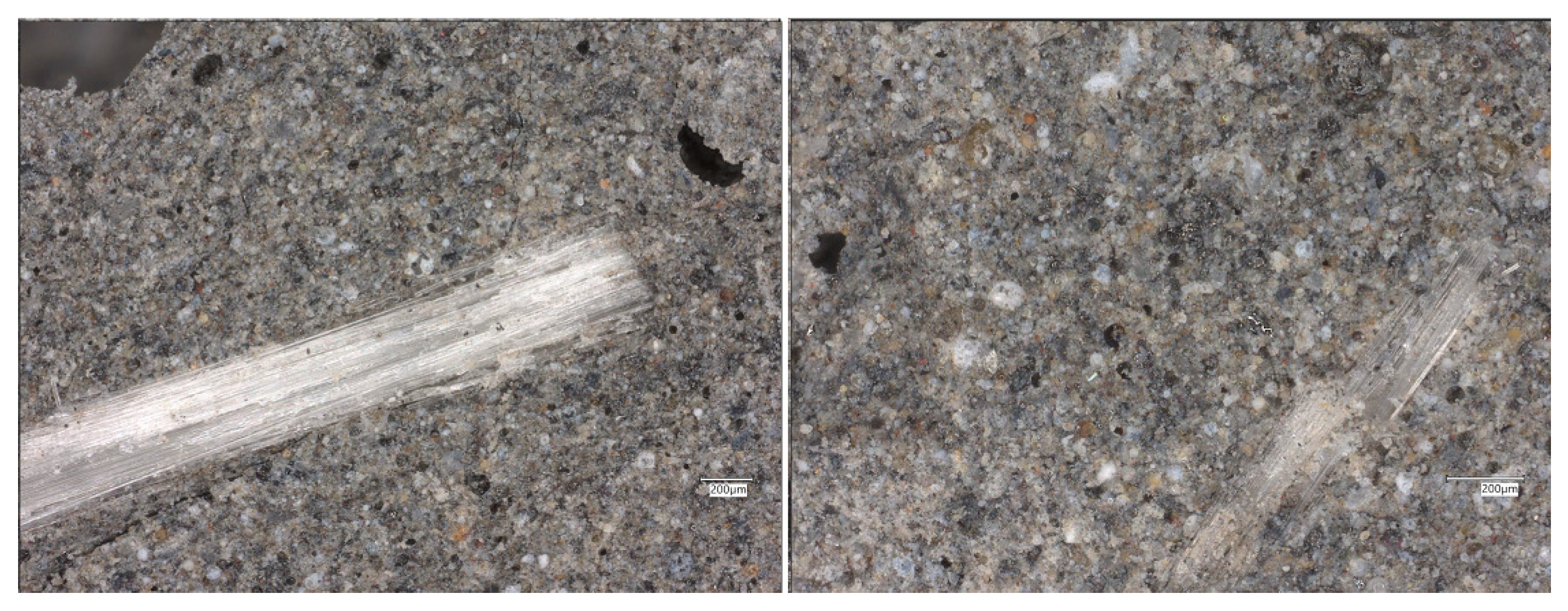

2.2.3. Optical and SEM Microscopy

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. X-Ray Diffraction

3.2. Compressive and Flexural Strength

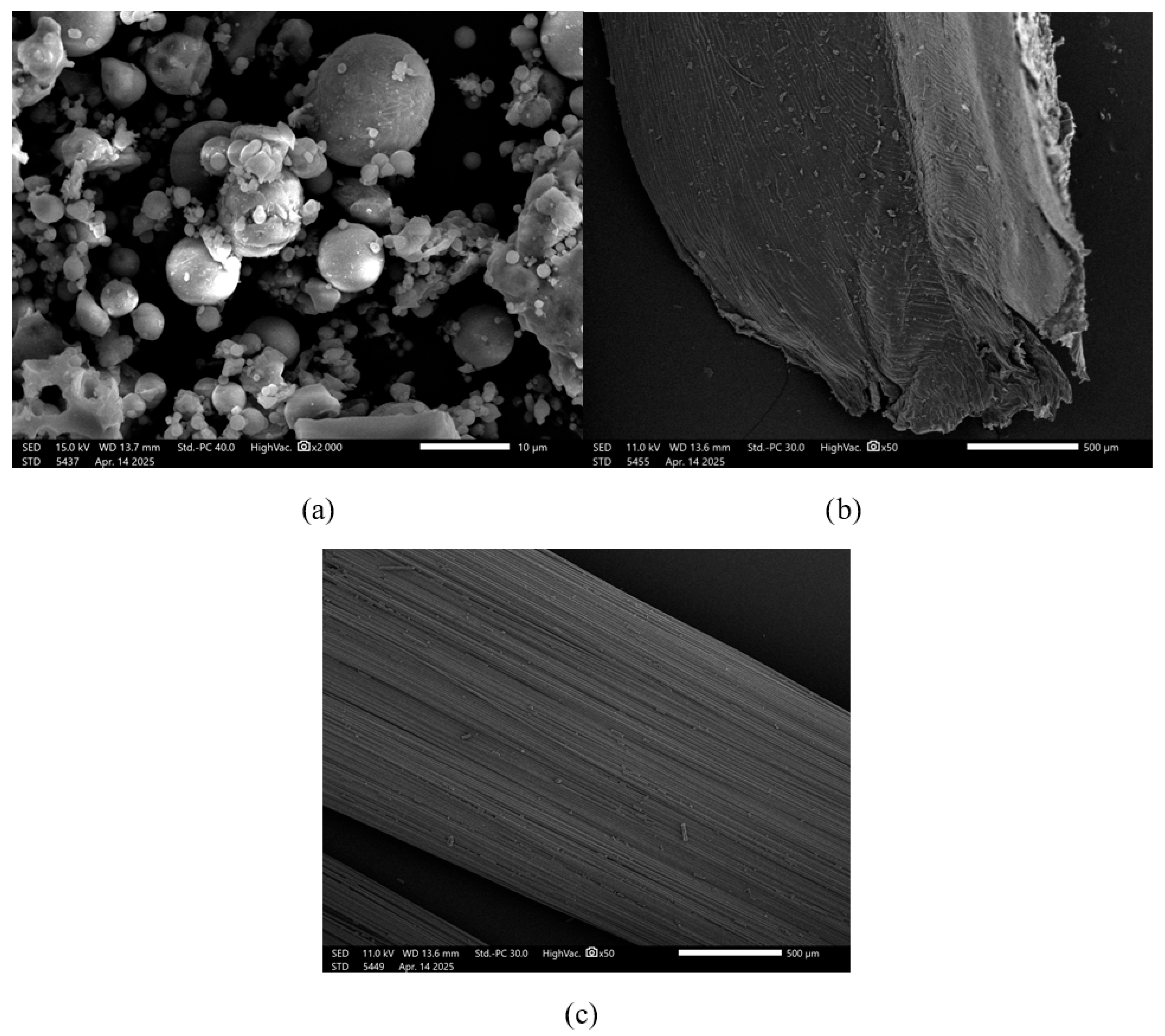

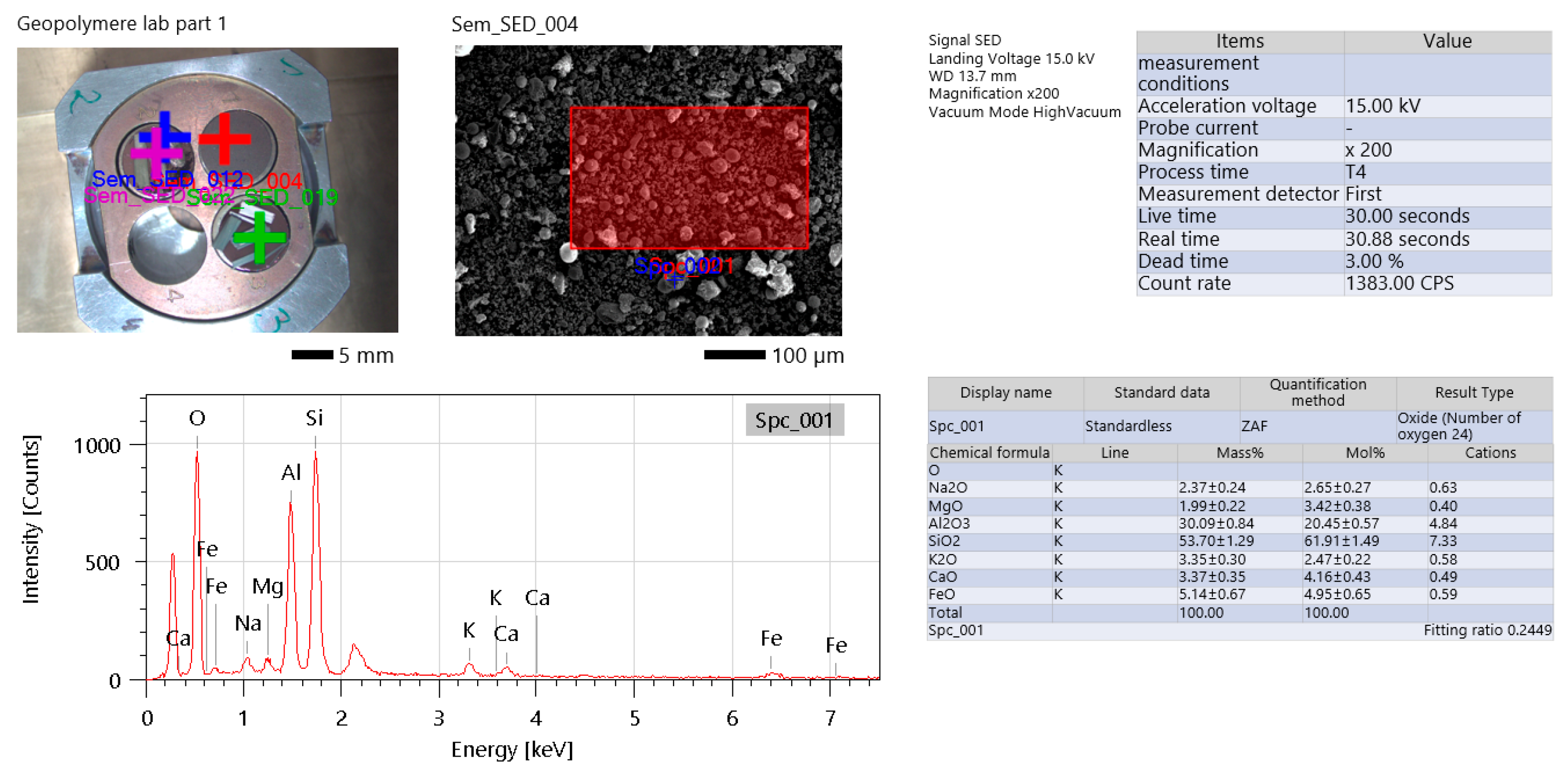

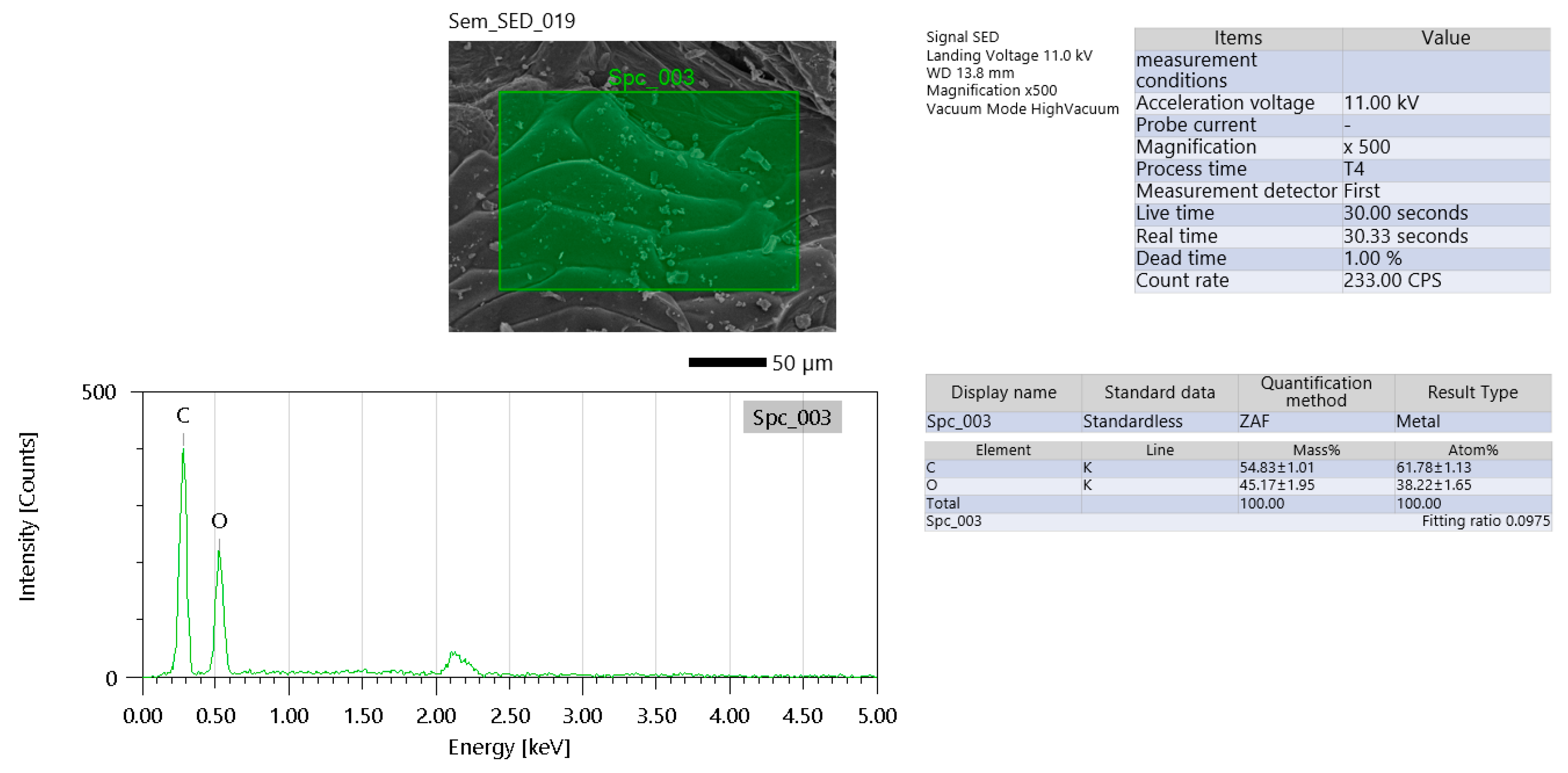

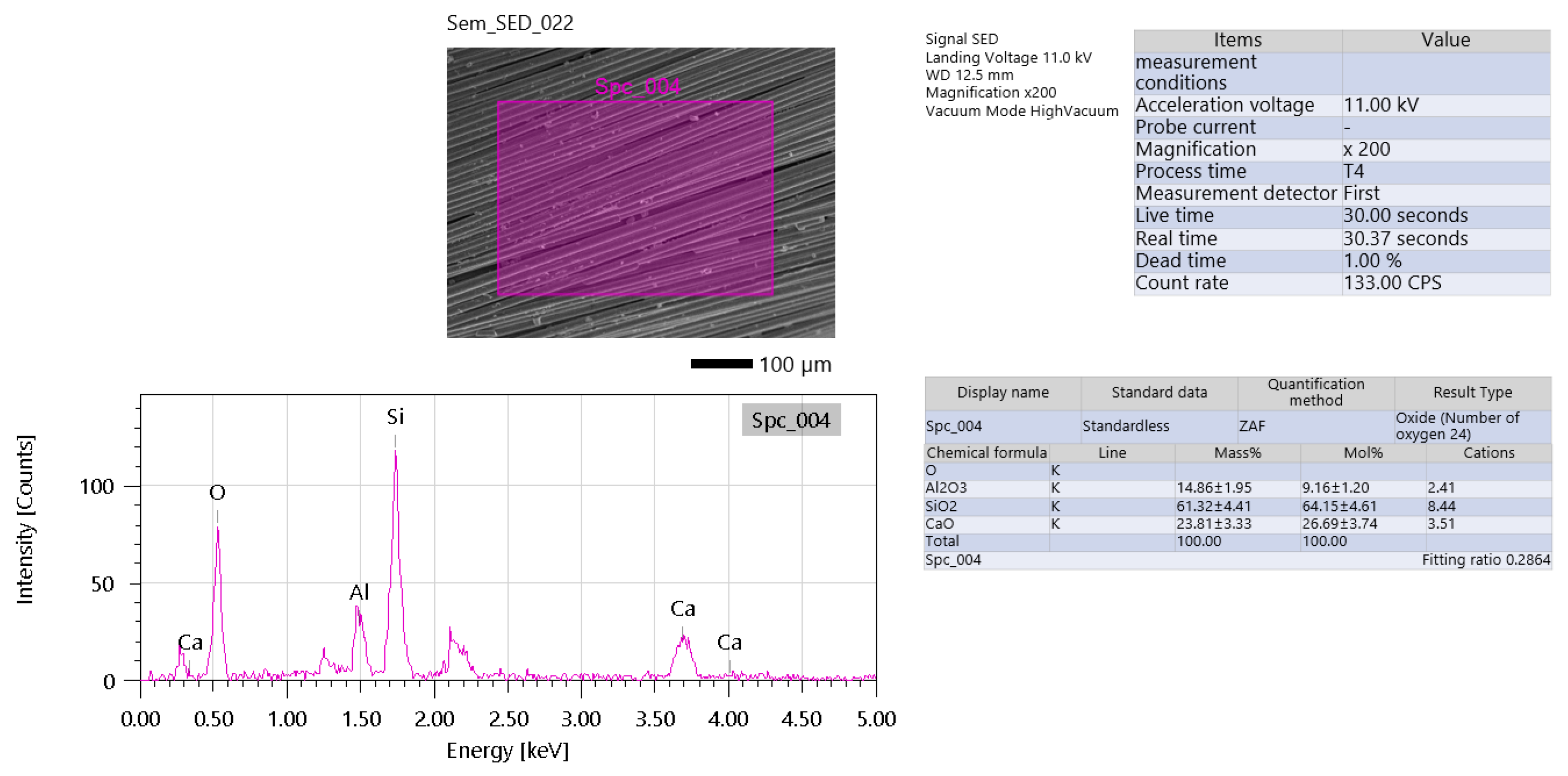

3.3. Optical and SEM Microscopy

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guo, T.; Cheng, Z.; Wang, C.; Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Cheng, Z. Compressive Properties and Microstructure of Hybrid Fiber-Reinforced Fly Ash/Slag-Based Geopolymers at Elevated Temperatures. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdellatief, M.; Elrahman, M.A.; Alanazi, H.; Abadel, A.A.; Tahwia, A. A State-of-the-Art Review on Geopolymer Foam Concrete with Solid Waste Materials: Components, Characteristics, and Microstructure. Innov. Infrastruct. Solut. 2023, 8, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, H.; Zang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Qian, H.; Zong, Z.; Cai, J.; Li, M.; Lin, Y. Comparative Study on Dynamic Compressive Properties and Sustainability Assessment of One-Part Fiber-Reinforced Geopolymer Composites. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mani, S.; Partheeban, P.; Gifta, C.C. A Comprehensive Review on Multilayered Natural-Fibre Composite Reinforcement in Geopolymer Concrete. Clean. Mater. 2025, 16, 100310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, X.; Huang, X.; Zhong, S.; Zhou, J. Advancing toward a Low-Carbon Infrastructure: Emission Reduction Potential of Geopolymer Road Maintenance. Mater. Today Sustain. 2025, 30, 101121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Alouani, M.; Saufi, H.; Aouan, B.; Bassam, R.; Alehyen, S.; Rachdi, Y.; El Hadki, H.; El Hadki, A.; Mabrouki, J.; Belaaouad, S.; et al. A Comprehensive Review of Synthesis, Characterization, and Applications of Aluminosilicate Materials-Based Geopolymers. Environ. Adv. 2024, 16, 100524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freire, A.L.; Da Silva, A.; Della Rocca, D.G.; Da Silveira Salla, J.; Castellã Pergher, S.B.; Rodríguez-Castellón, E.; José, H.J.; De Fátima Peralta Muniz Moreira, R. Synthesis and Characterization of Geopolymers Based on Phosphate Mining Tailings and Its Application for Carbon Dioxide and Nitrogen Adsorption. Ceram. Int. 2025, 51, 8396–8407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, E.; Özen, S. Enhancing Geopolymer Synthesis through Calcination: Increasing the Potential of Natural Material Utilization. Open Ceram. 2025, 22, 100796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, Y.; Cui, H.; Xue, J. Improved Mechanical and Thermal Properties of Sustainable Ultra-High Performance Geopolymer Concrete with Cellulose Nanofibres. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 102, 112068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Figiela, B.; Miernik, K.; Ziejewska, C.; Marczyk, J.; Hebda, M.; Cheng, A.; Lin, W.-T. Mechanical and Fracture Properties of Long Fiber Reinforced Geopolymer Composites. Materials 2021, 14, 5183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, L.; Chouw, N.; Jayaraman, K. Flax Fibre and Its Composites—A Review. Compos. Part B Eng. 2014, 56, 296–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahıskalı, A.; Benli, A.; Ahıskalı, M.; Bayraktar, O.Y.; Kaplan, G. Sustainable Geopolymer Foam Concrete with Recycled Crumb Rubber and Dual Fiber Reinforcement of Polypropylene and Glass Fibers: A Comprehensive Study. Constr. Build. Mater. 2025, 474, 141137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dal Poggetto, G.; D’Angelo, A.; Blanco, I.; Piccolella, S.; Leonelli, C.; Catauro, M. FT-IR Study, Thermal Analysis, and Evaluation of the Antibacterial Activity of a MK-Geopolymer Mortar Using Glass Waste as Fine Aggregate. Polymers 2021, 13, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; He, M.; He, Y.; Ou, Z. The Synergistic Enhancement of Bending and Compression Properties of Glass Fiber Reinforced Phosphate Activated Metakaolin Geopolymer. Case Stud. Constr. Mater. 2025, 22, e04527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, V.S.; Buczkowska, K.E.; Ercoli, R.; Pławecka, K.; Marian, N.M.; Louda, P. Influence of Incorporating Recycled Windshield Glass, PVB-Foil, and Rubber Granulates on the Properties of Geopolymer Composites and Concretes. Polymers 2023, 15, 2122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Łach, M.; Chou, S.-Y.; Lin, W.-T.; Cheng, A.; Hebdowska-Krupa, M.; Gądek, S.; Mikuła, J. Mechanical Properties of Short Fiber-Reinforced Geopolymers Made by Casted and 3D Printing Methods: A Comparative Study. Materials 2020, 13, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xiao, R.; Jiang, X.; Li, W.; Zhu, X.; Huang, B. Effect of Particle Size and Curing Temperature on Mechanical and Microstructural Properties of Waste Glass-Slag-Based and Waste Glass-Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 273, 122970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziejewska, C.; Grela, A.; Mierzwiński, D.; Hebda, M. Influence of Waste Glass Addition on the Fire Resistance, Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Geopolymer Composites. Materials 2023, 16, 6011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazorenko, G.; Kasprzhitskii, A.; Yavna, V.; Mischinenko, V.; Kukharskii, A.; Kruglikov, A.; Kolodina, A.; Yalovega, G. Effect of Pre-Treatment of Flax Tows on Mechanical Properties and Microstructure of Natural Fiber Reinforced Geopolymer Composites. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 20, 101105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, K.; Matsagar, V.A.; Kodur, V.R. Recent Advances in the Use of Natural Fibers in Civil Engineering Structures. Constr. Build. Mater. 2024, 411, 134364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moujoud, Z.; Sair, S.; Ait Ousaleh, H.; Ayouch, I.; El Bouari, A.; Tanane, O. Geopolymer Composites Reinforced with Natural Fibers: A Review of Recent Advances in Processing and Properties. Constr. Build. Mater. 2023, 388, 131666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Liu, J. Alkaline Degradation of Plant Fiber Reinforcements in Geopolymer: A Review. Molecules 2023, 28, 1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozub, B.; Dudek, J.; Melnychuk, M. The Effect of Oil Additives on the Properties of Fly Ash-Based Foamed Geopolymers. Materials 2024, 17, 5819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brugaletta, F.; Becher, A.F.; Rostagno, D.L.; Kim, J.; Fresneda Medina, J.I.; Ziejewska, C.; Marczyk, J.; Korniejenko, K. The Different Properties of Geopolymer Composites Reinforced with Flax Fibers and Carbon Fibers. Materials 2024, 17, 2633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Łach, M.; Mikuła, J. The Influence of Short Coir, Glass and Carbon Fibers on the Properties of Composites with Geopolymer Matrix. Materials 2021, 14, 4599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ionescu, B.A.; Chira, M.; Vermeșan, H.; Hegyi, A.; Lăzărescu, A.-V.; Thalmaier, G.; Neamțu, B.V.; Gabor, T.; Sur, I.M. Influence of Fe2O3, MgO and Molarity of NaOH Solution on the Mechanical Properties of Fly Ash-Based Geopolymers. Materials 2022, 15, 6965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kmiotek, A.; Figiela, B.; Łach, M.; Aruova, L.; Korniejenko, K. An Investigation of Key Mechanical and Physical Characteristics of Geopolymer Composites for Sustainable Road Infrastructure Applications. Buildings 2025, 15, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zvir, Y.; Pimentel, C.; Pina, C.M. The Effect of Stoichiometry, Mg-Ca Distribution, and Iron, Manganese, and Zinc Impurities on the Dolomite Order Degree: A Theoretical Study. Minerals 2021, 11, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obonyo, E.; Kamseu, E.; Lemougna, P.; Tchamba, A.; Melo, U.; Leonelli, C. A Sustainable Approach for the Geopolymerization of Natural Iron-Rich Aluminosilicate Materials. Sustainability 2014, 6, 5535–5553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erunkulu, I.O.; Malumbela, G.; Oladijo, O.P. Feasibility of Geopolymer Synthesis Using Soda Ash in Copper Slag Blended Fly Ash-Based Geopolymer. Mater. Today Proc. 2023, 86, 41–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madirisha, M.M.; Dada, O.R.; Ikotun, B.D. Chemical Fundamentals of Geopolymers in Sustainable Construction. Mater. Today Sustain. 2024, 27, 100842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayerhofer, A.; You, D.; Presoly, P.; Bernhard, C.; Michelic, S.K. Study on the Possible Error Due to Matrix Interaction in Automated SEM/EDS Analysis of Nonmetallic Inclusions in Steel by Thermodynamics, Kinetics and Electrolytic Extraction. Metals 2020, 10, 860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesamoorthy, R.; Suresh, G.; Padmavathi, K.R.; Rajaparthiban, J.; Vezhavendhan, R.; Bharathiraja, G. Experimental Analysis and Mechanical Properties of Fly-Ash Loaded E-Glass Fiber Reinforced IPN (Vinylester/Polyurethane) Composite. Fibers Polym. 2022, 23, 2916–2926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASTM C78/C78M-18; Standard Test Method for Flexural Strength of Concrete (Using Simple Beam with Third-Point Loading). ASTM: West Conshohocken, PA, USA, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Tome, S.; Nana, A.; Tchakouté, H.K.; Temuujin, J.; Rüscher, C.H. Mineralogical Evolution of Raw Materials Transformed to Geopolymer Materials: A Review. Ceram. Int. 2024, 50, 35855–35868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rattanasak, U.; Pankhet, K.; Chindaprasirt, P. Effect of Chemical Admixtures on Properties of High-Calcium Fly Ash Geopolymer. Int. J. Min. Met. Mater. 2011, 18, 364–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amran, Y.H.M.; Alyousef, R.; Alabduljabbar, H.; El-Zeadani, M. Clean Production and Properties of Geopolymer Concrete; A Review. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 251, 119679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amar, M.; Ladduri, B.; Alloul, A.; Benzerzour, M.; Abriak, N.-E. Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of Geopolymers Utilizing Excavated Soils, Metakaolin and Slags. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 86, 108755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbhuiya, S.; Pang, E. Strength and Microstructure of Geopolymer Based on Fly Ash and Metakaolin. Materials 2022, 15, 3732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, X.; Tabil, L.G.; Panigrahi, S. Chemical Treatments of Natural Fiber for Use in Natural Fiber-Reinforced Composites: A Review. J. Polym. Environ. 2007, 15, 25–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neto, J.S.S.; Lima, R.A.A.; Cavalcanti, D.K.K.; Souza, J.P.B.; Aguiar, R.A.A.; Banea, M.D. Effect of Chemical Treatment on the Thermal Properties of Hybrid Natural Fiber-reinforced Composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2019, 136, 47154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korniejenko, K.; Łach, M. Geopolymers Reinforced by Short and Long Fibres—Innovative Materials for Additive Manufacturing. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 2020, 28, 167–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Geopolymer | Fly Ash [g] | Alkaline Solution [g] | Glass Fiber [g] | Flax Fiber [g] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. | 3000 | 1800 | - | - |

| 2. | 3500 | 1800 | 35 | - |

| 3. | 3500 | 1800 | - | 35 |

| 4. | 3500 | 1800 | 17.5 | 17.5 |

| No | Geopolymer Type | Compressive Strength | Flexural Strength | ρ (g/cm3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fly Ash | 16.94 | 5.49 | 1.62 |

| 2 | Fly Ash–Flax Fiber–Glass Fiber | 15.56 | 3.00 | 1.51 |

| 3 | Fly Ash–Flax Fiber | 15.45 | 3.57 | 1.48 |

| 4 | Fly Ash–Glass Fiber | 28.70 | 3.45 | 1.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Oliwa, K.; Efe, S.; Figiela, B.; Korniejenko, K. Synergistic Effects of Glass and Flax Fibers Reinforced in Fly Ash Geopolymer Matrix. Materials 2026, 19, 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010102

Oliwa K, Efe S, Figiela B, Korniejenko K. Synergistic Effects of Glass and Flax Fibers Reinforced in Fly Ash Geopolymer Matrix. Materials. 2026; 19(1):102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010102

Chicago/Turabian StyleOliwa, Kacper, Semanur Efe, Beata Figiela, and Kinga Korniejenko. 2026. "Synergistic Effects of Glass and Flax Fibers Reinforced in Fly Ash Geopolymer Matrix" Materials 19, no. 1: 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010102

APA StyleOliwa, K., Efe, S., Figiela, B., & Korniejenko, K. (2026). Synergistic Effects of Glass and Flax Fibers Reinforced in Fly Ash Geopolymer Matrix. Materials, 19(1), 102. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma19010102