Design and Analysis of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Structural Design and Working Principle of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform

2.1. Platform Structure

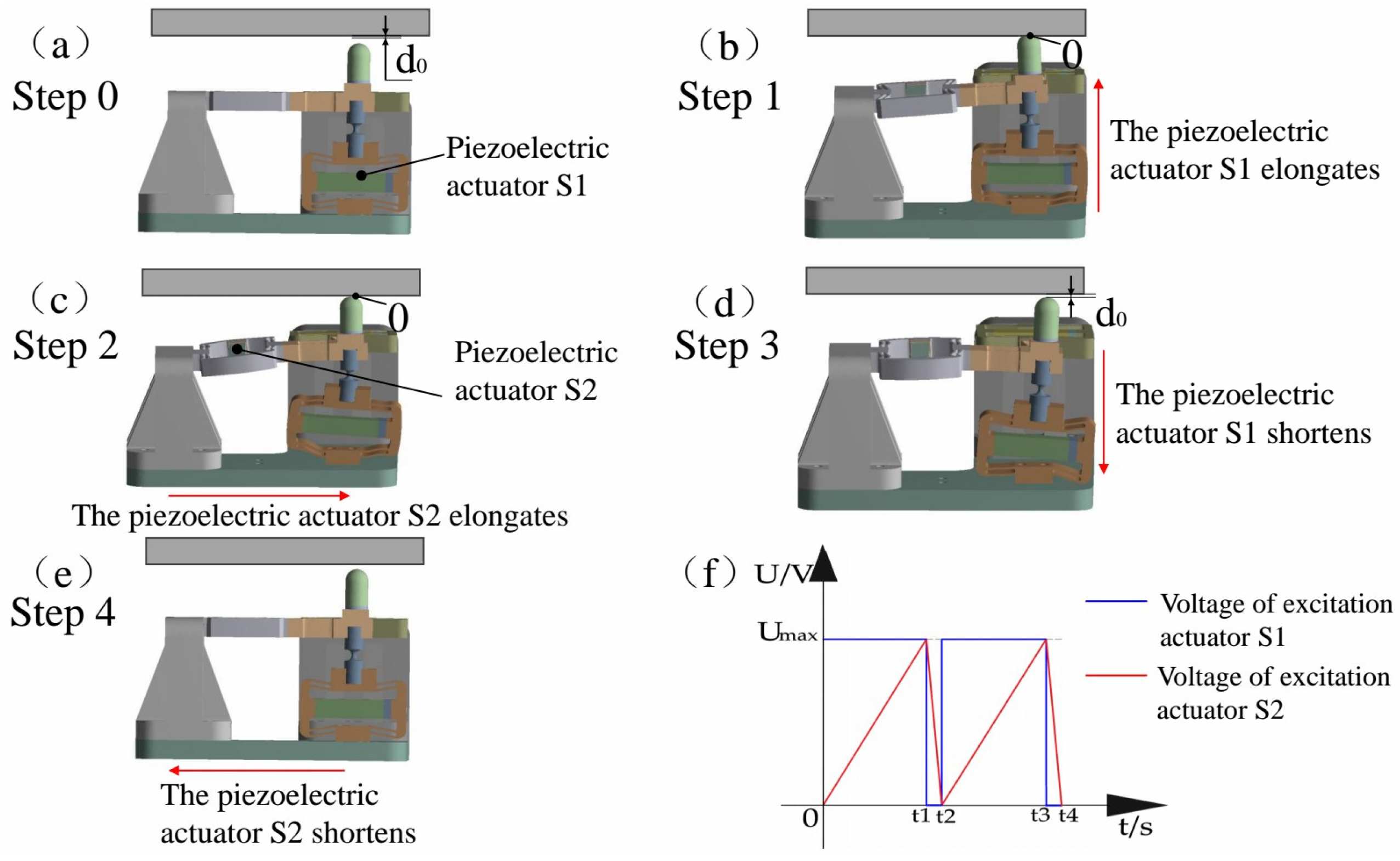

2.2. Platform Working Principle

3. Theoretical Modeling and Simulation of the Driving Stators

3.1. The Establishment of the Output Displacement Model

3.2. Finite Element Analysis of the Stator

4. Experimental Study on Inertial Platforms

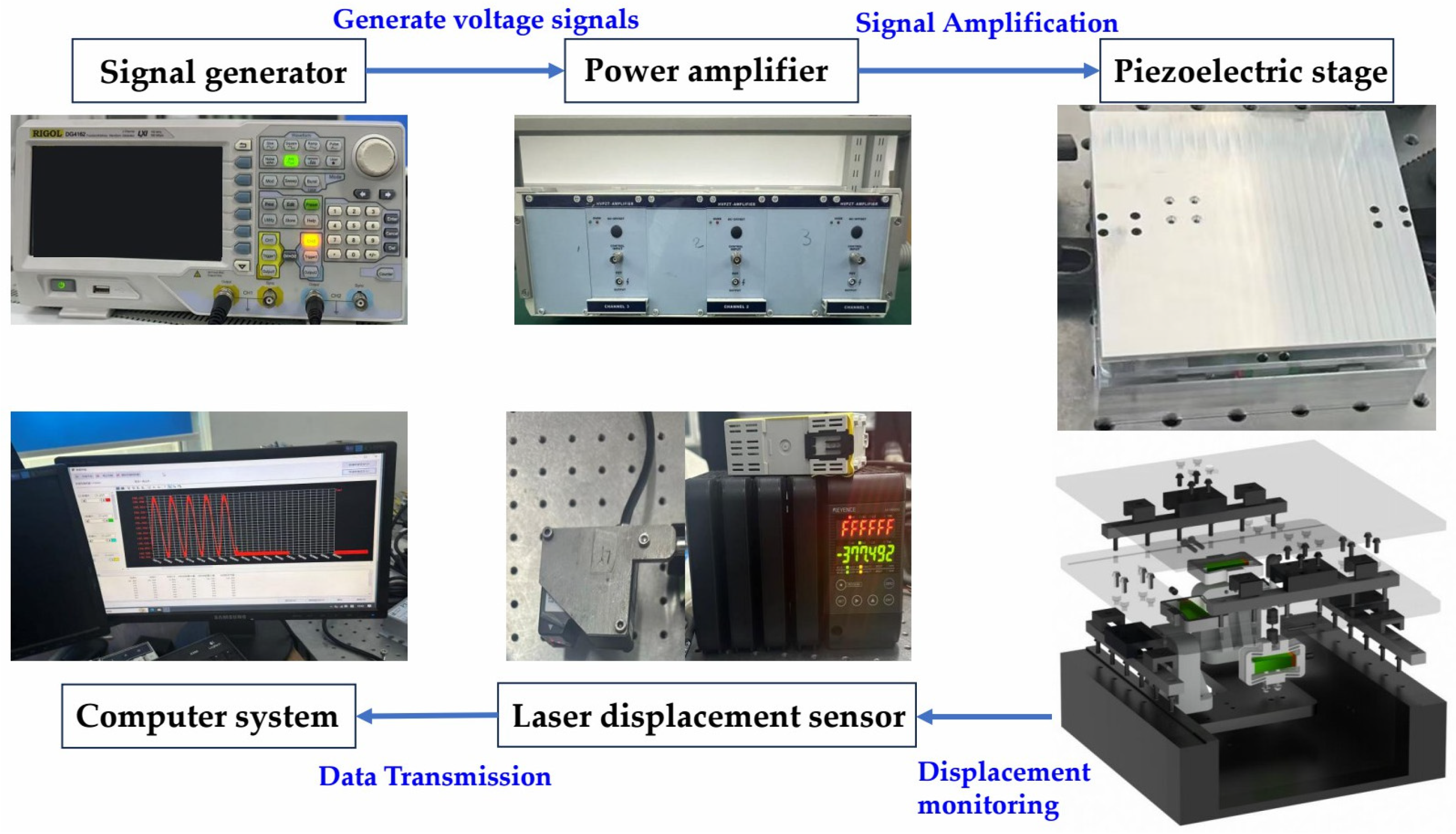

4.1. Construction of the Experimental System

4.2. Displacement Backlash in a Traditional Inertial-Drive Prototype

4.3. Fundamental Experiments on the Proposed Backlash Mitigation Model

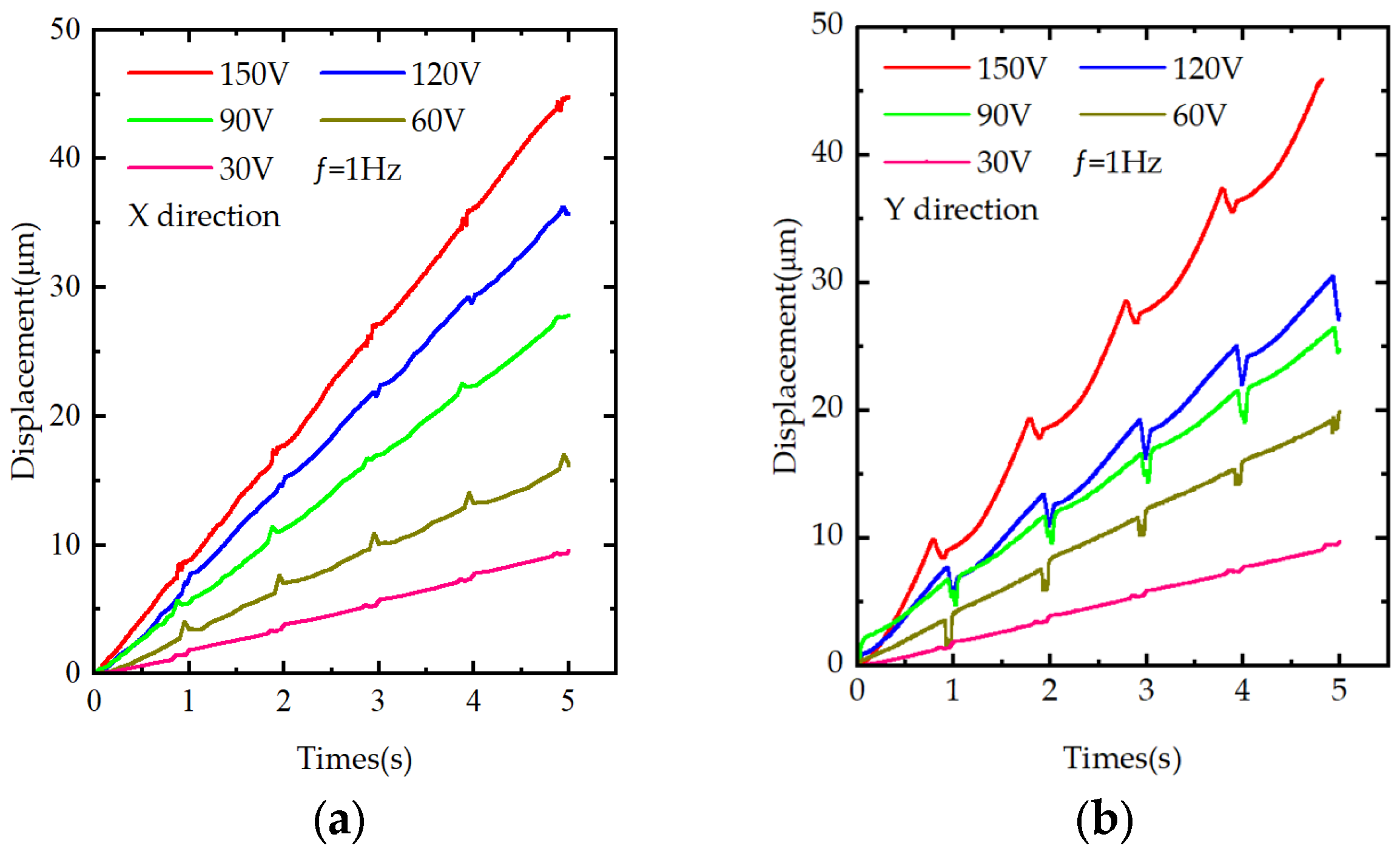

4.3.1. Displacement Experiments

4.3.2. Speed Experiments

4.3.3. Displacement Resolution Experiments

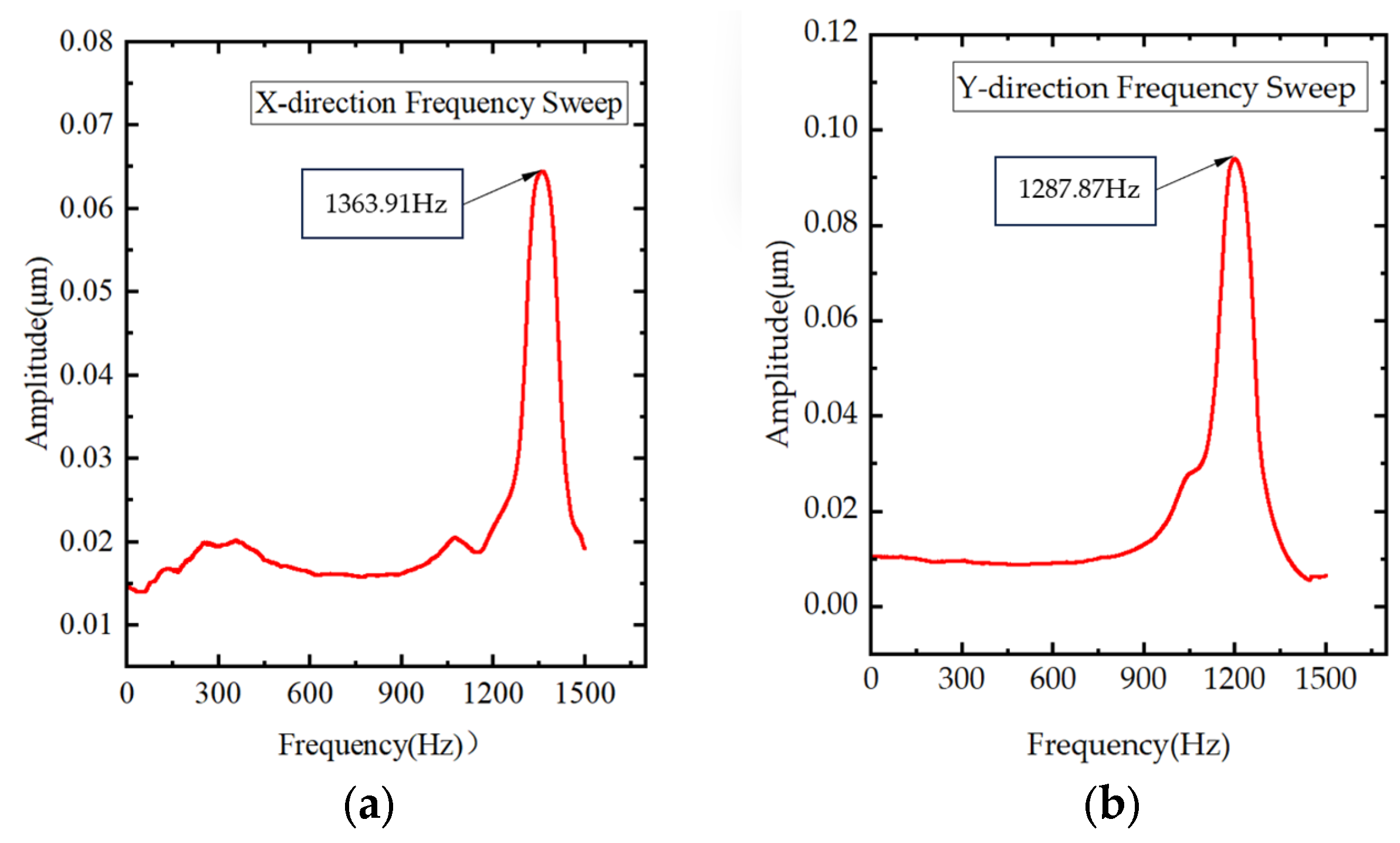

4.3.4. Resonant Frequency Experiments

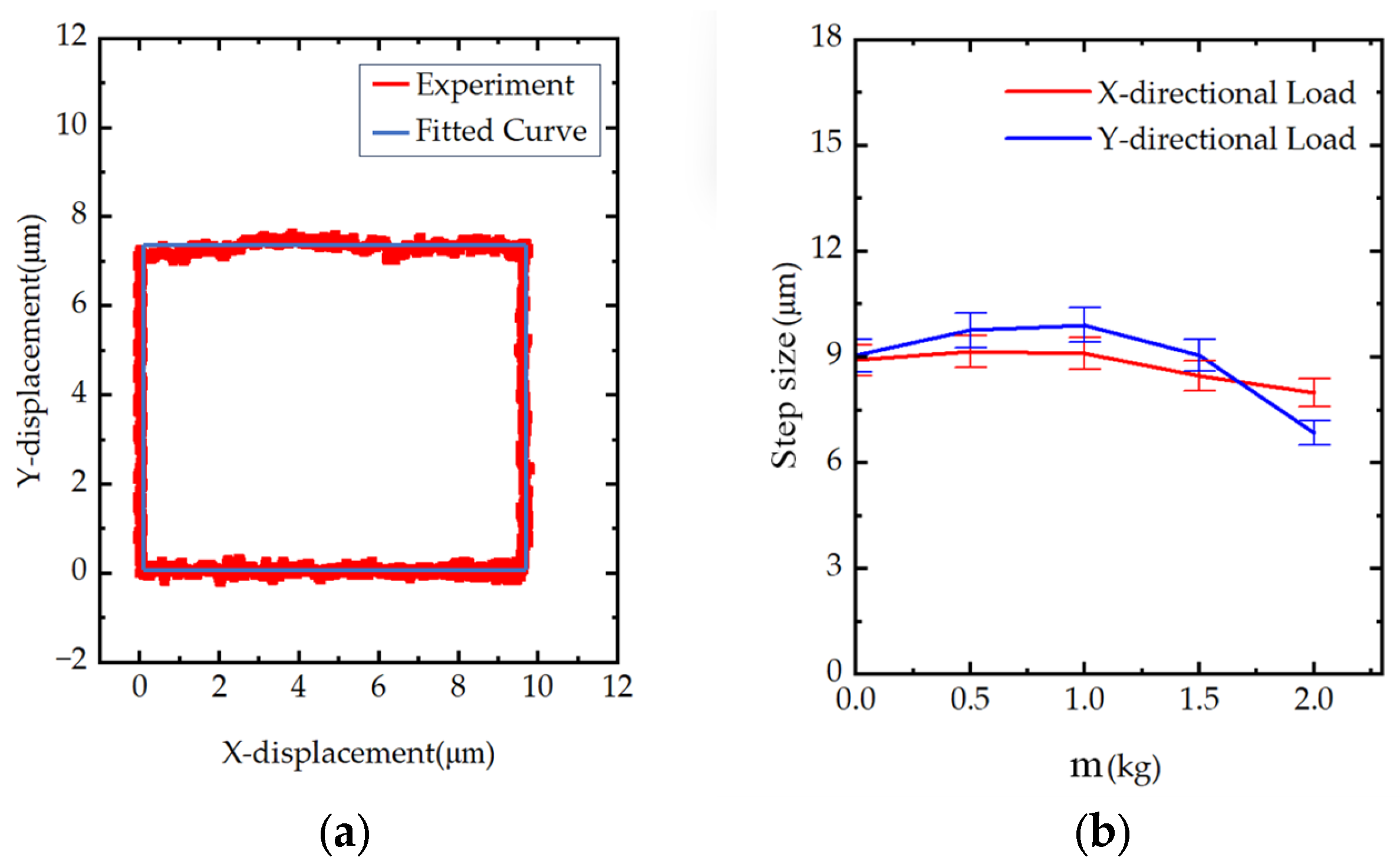

4.3.5. Trajectory Experiments

4.3.6. The Prototype With-Load Experiments

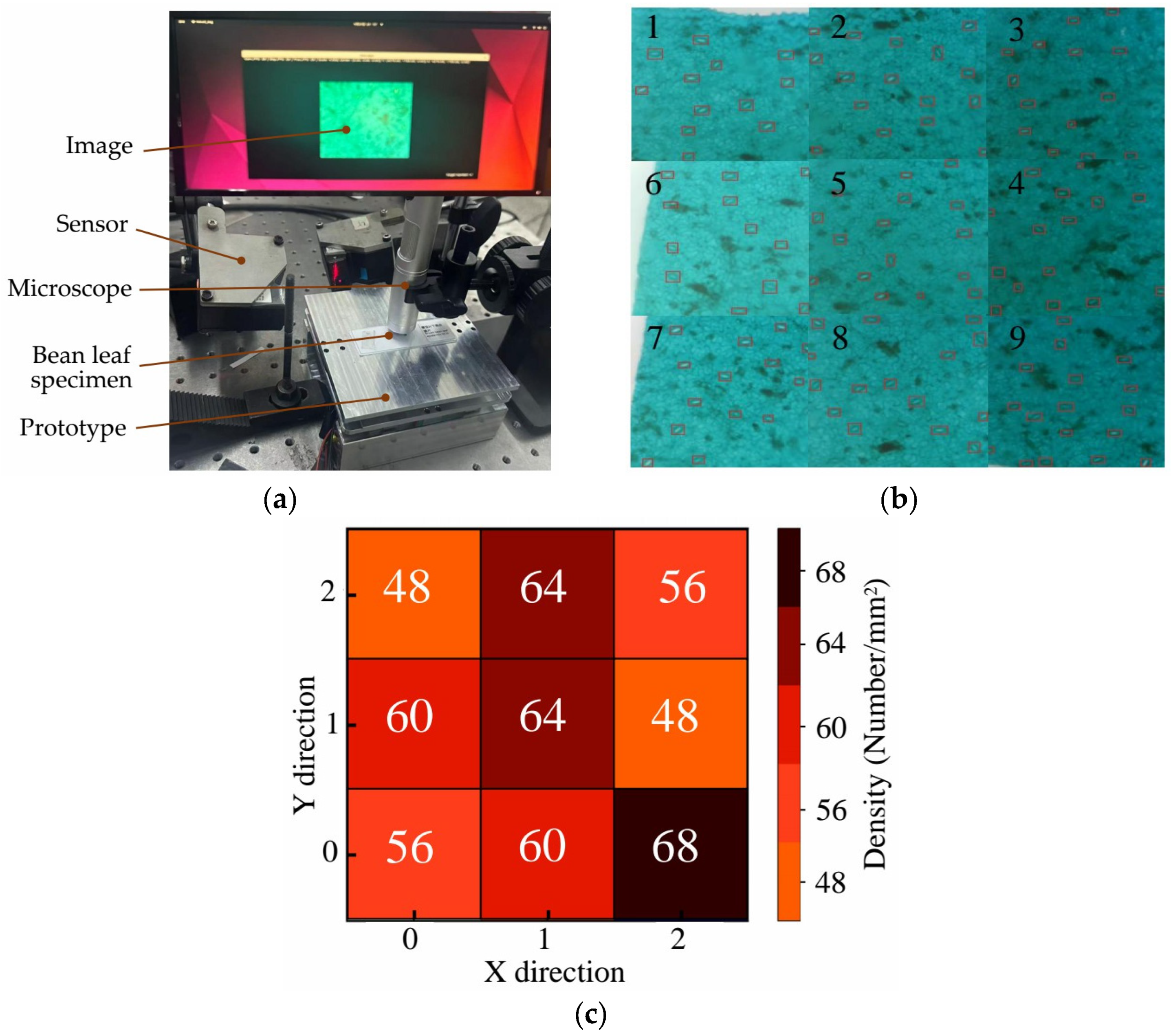

4.3.7. Application Experiments

5. Conclusions

- Compared with traditional piezoelectric positioning platforms, the proposed platform employs a novel three-degree-of-freedom (3-DOF) piezoelectric stator, providing a new approach to addressing backlash in inertial actuation.

- Experimental results show that the motion range of the platform is 15 mm × 15 mm; the displacement backlash rates in the X and Y directions range from 0% to 9.84% and 0% to 28.42%, respectively; the speeds are 177.3 μm/s and 130.4 μm/s, respectively; the displacement resolutions can reach 11.39 nm and 13.61 nm, respectively; the platform can withstand a weight of at least 2 kg or less; and the resonant frequencies in the X and Y directions are 1363.91 Hz and 1287.87 Hz, respectively.

- The application study demonstrates the successful use of the 2-DOF platform for precision motion positioning of plant specimens under an optical microscope and for assisting in the observation of plant stomatal density, indicating its potential for botany-related microscopic observation.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zate, T.T.; Abdurrahmanoglu, C.; Esposito, V.; Haugen, A.B. Textured lead-free piezoelectric ceramics: A review of template effects. Materials 2025, 18, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.H. Microstructure and piezoelectric properties of lead zirconate titanate nanocomposites reinforced with in-situ formed ZrO2 nanoparticles. Materials 2022, 15, 1389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toda, Y.; Tameshige, T.; Tomiyama, M.; Kinoshita, T.; Shimizu, K.K. An affordable image-analysis platform to accelerate stomatal phenotyping during microscopic observation. Front. Plant Sci. 2021, 12, 793369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, X.Y.; Xu, X.C.; Wang, Z.W.; He, L.; Zhang, K.Q.; Liang, B.; Ye, J.L.; Shi, J.W.; Wu, X.; Dai, M.Q.; et al. StomataScorer: A portable and high-throughput leaf stomata trait scorer combined with deep learning and an improved CV model. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2022, 20, 577–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.R.; Lai, Y.L.; Xu, S.Y.; Zhu, M.F.; Sun, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zhao, G. A self-powered controllable microneedle drug delivery system for rapid blood pressure reduction. Nano Energy 2024, 123, 109344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, B.Y.; Xu, G.; Shao, J.Y. Validation, in-depth analysis, and modification of the micropipette aspiration technique. Cell. Mol. Bioeng. 2009, 2, 351–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liu, K.; Jiang, Y.; Hao, M.; Chen, S.L.; Ning, Y.C.; Ning, J.X. Study of cell-trap microfluidic chip for platinum drugs treating cancer cell tests. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE 12th International Conference on Nano/Micro Engineered and Molecular Systems (NEMS), Los Angeles, CA, USA, 9–12 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Fang, T.; Shang, W.H.; Liu, C.; Xu, J.J.; Zhao, D.P.; Liu, Y.Y.; Ye, A.P. Nondestructive identification and accurate isolation of single cells through a chip with Raman optical tweezers. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 9932–9939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, J.; Liu, S.H.; Liu, Y.X.; Wang, L.; Gao, X.; Li, K. A 2-DOF needle insertion device using inertial piezoelectric actuator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2021, 69, 3918–3927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.Y.; Li, Z.M.; Wu, J.G.; Xin, X.D.; Shen, X.Y.; Yuan, X.T.; Yang, J.K.; Chu, Z.Q.; Dong, S.X. A piezoelectric and electromagnetic dual mechanism multimodal linear actuator for generating macro-and nanomotion. Research 2019, 2019, 8232097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.K.; Li, Y.J.; Li, H.L. Simulation-based estimation of thermal behavior of direct feed drive mechanism with updated finite element model. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 2014, 27, 992–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, H.Y.; Ding, B.; Zhao, F.; Zhou, M.; Zhu, F.; Cai, J.D. Adaptive terminal sliding mode control for permanent magnet linear synchronous motor. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application (ICHVE), Beijing, China, 6–10 September 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, Q.B.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.X.; Zhang, S.J.; Chen, W.S.; Zhao, J. Research on a locking device for power-off locking and 2-DOF backward motion suppression of a piezoelectric platform. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 71, 1790–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.K.; Peng, Y.X.; Sun, Z.X.; Yu, H.Y. A novel stick–slip piezoelectric actuator based on a triangular compliant driving mechanism. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 5374–5382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yun, H.; Kong, D.Q.; Aoyagi, M. Development of a multi-drive-mode piezoelectric linear actuator with parallel-arrangement dual stator. Precis. Eng. 2022, 77, 127–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.M.; Hu, Y.L.; Shen, D.Z.; Ma, J.J.; Li, J.P.; Wen, J.M. A novel piezoelectric inchworm actuator driven by one channel direct current signal. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2020, 68, 2015–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Yang, Z.X.; Wang, K.F.; Li, X.; Liu, Y.W.; Dong, J.S.; Huang, H. A bionic inertial piezoelectric actuator with improved frequency bandwidth. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 156, 107620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, B.W.; Zhu, J.; Jin, Z.Q.; He, H.D.; Wang, Z.H.; Sun, L.N. A large thrust trans-scale precision positioning platform based on the inertial stick–slip driving. Microsyst. Technol. 2019, 25, 3713–3721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakotondrabe, M.; Haddab, Y.; Lutz, P. Development, modeling, and control of a micro-/nanopositioning 2-dof stick–slip device. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2009, 14, 733–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhu, J.H.; Pang, M.; Luo, J.; Xie, S.R.; Liu, M. A stick-slip positioning platform robust to load variations. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2016, 21, 2165–2173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Z.; Zhang, Y.L.; Xu, Q.S. Design and control of a novel piezo-driven XY parallel nanopositioning platform. Microsyst. Technol. 2017, 23, 1067–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abedi, K.; Shakhesi, E.; Seraj, H.; Mahnama, M.; Shirazi, F.A. Design and analysis of a 2-DOF compliant serial micropositioner based on “S-shaped” flexure hinge. Precis. Eng. 2023, 83, 228–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.Y.; Zhu, L.M.; Su, C.Y.; Ding, H. Motion control of piezoelectric positioning platforms: Modeling, controller design, and experimental evaluation. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2013, 18, 1459–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.Y.; Li, C.X.; Zhu, L.M.; Su, C.Y. Modeling and identification of piezoelectric-actuated platforms cascading hysteresis nonlinearity with linear dynamics. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 21, 1792–1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.W.; Fu, L.; Ren, L.Q.; Huang, H.; Fan, Z.Q.; Li, J.P.; Qu, H. Design and experimental research of a novel inchworm type piezo-driven rotary actuator with the changeable clamping radius. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2013, 84, 015006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, Z.C.; Dong, J.S.; Zhou, X.Q.; Xu, Z.; Qiu, W.; Shen, C.L. Achieving smooth motion of stick–slip piezoelectric actuator by means of alternate stepping. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 181, 109494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, F.; Tian, L.Y.; Huang, H.; Wang, J.R.; Liang, T.W.; Zu, X.Y.; Zhao, H.W. Actively controlling the contact force of a stick-slip piezoelectric linear actuator by a composite flexible hinge. Sens. Actuator A-Phys. 2019, 299, 111606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Cai, J.J.; Wen, J.M.; Yao, J.F.; Huang, J.S.; Zhao, T.; Wan, N. A walking type piezoelectric actuator with two umbrella-shaped flexure mechanisms. Smart Mater. Struct. 2020, 29, 085014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.X.; Fan, Z.Q.; Ma, Z.C.; Zhao, H.W.; Guo, Y.; Hong, K.; Li, Y.S.; Liu, H.; Wu, D. Design and experimental research of a novel stick-slip type piezoelectric actuator. Micromachines 2017, 8, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.Y.; Fan, H.Y.; Liu, J.H.; Huang, H. Suppressing the backward motion of a stick–slip piezoelectric actuator by means of the sequential control method (SCM). Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 143, 106855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, B.; Hu, H.; Lei, Y.L.; Chen, J. Design and experimental investigation of a novel stick-slip piezoelectric actuator based on V-shaped driving mechanism. Mechatronics 2023, 95, 103067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, J.; Peng, H.T.; Duan, Y.Z.; Rakotondrabe, M. Reducing backward motion of stick-slip piezoelectric actuators using dual driving feet designed by asymmetric stiffness principle. Mech. Mach. Theory 2024, 203, 105810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.; Gweon, D. Development of flexure based 6-degrees of freedom parallel nano-positioning system with large displacement. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 2012, 83, 035003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.P.; Liu, Y.X.; Deng, J.; Zhang, S.J.; Chen, W.S. A collaborative excitation method for piezoelectric stick-slip actuator to eliminate rollback and generate precise smooth motion. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2022, 170, 108815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.X.; Zhang, S.J.; Deng, J.; Liu, Y.X. A 2-DOF High-Performances Platform Using a Longitudinal-Bending-Bending Piezoelectric Actuator. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2025, 72, 10455–10464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Q.R.; Zheng, Y.J.; Jin, J.; Hu, N.D.; Zhang, Z.L.; Hu, H.P. Design and experimental study of a stepping piezoelectric actuator with large stroke and high speed. Micromachines 2023, 13, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boudaoud, M.; Lu, T.M.; Liang, S.; Oubellil, R.; Régnier, S. A voltage/frequency modeling for a multi-DOFs serial nanorobotic system based on piezoelectric inertial actuators. IEEE-ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2018, 23, 2814–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, J.C.; Ning, C.; Liu, Y.X.; Howard, I. Piezoelectric inertial robot for operating in small pipelines based on stick-slip mechanism: Modeling and experiment. Front. Mech. Eng. 2022, 17, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiao, G.D.; Ning, P.; Gao, Q.; Yu, Y.; Lu, X.H.; Yang, S.T.; Cheng, T.H. A flexure hinged piezoelectric stick–slip actuator with high velocity and linearity for long-stroke nano-positioning. Smart Mater. Struct. 2022, 31, 075017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.P.; Huang, H.; Zhao, H.W. A piezoelectric-driven linear actuator by means of coupling motion. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2017, 65, 2458–2466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.G.; Li, Y.M.; Xie, Y.L.; Wang, R.B. Design and analysis of new ultra compact decoupled XYZθ platform to achieve large-scale high precision motion. Mech. Mach. Theory 2022, 167, 104527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, G.Y.; Zhu, L.M.; Su, C.Y.; Ding, H.; Fatikow, S. Modeling and control of piezo-actuated nanopositioning platforms: A survey. IEEE Trans. Autom. Sci. Eng. 2014, 13, 313–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Material Parameters | Parameter Value | Material Parameters | Parameter Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| la (mm) | 5 | E (GPa) | 210 |

| h (mm) | 0.5 | Ρ (kg/m3) | 7850 |

| t (mm) | 1 | μ | 0.3 |

| d (mm) | 28 | FPZT (N) | 2000 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chang, Q.; Xu, Y.; Deng, X.; Liu, X.; Zhu, L.; Li, J.; Liu, Y. Design and Analysis of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform. Materials 2025, 18, 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214995

Chang Q, Xu Y, Deng X, Liu X, Zhu L, Li J, Liu Y. Design and Analysis of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform. Materials. 2025; 18(21):4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214995

Chicago/Turabian StyleChang, Qingbing, Yicheng Xu, Xian Deng, Xuan Liu, Liangkuan Zhu, Jian Li, and Yingxiang Liu. 2025. "Design and Analysis of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform" Materials 18, no. 21: 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214995

APA StyleChang, Q., Xu, Y., Deng, X., Liu, X., Zhu, L., Li, J., & Liu, Y. (2025). Design and Analysis of a Two-Degree-of-Freedom Inertial Piezoelectric Platform. Materials, 18(21), 4995. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18214995