Optimizing Volumetric Ratio and Supporting Electrolyte of Tiron-A/Tungstosilicic Acid Derived Redox Flow Battery

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

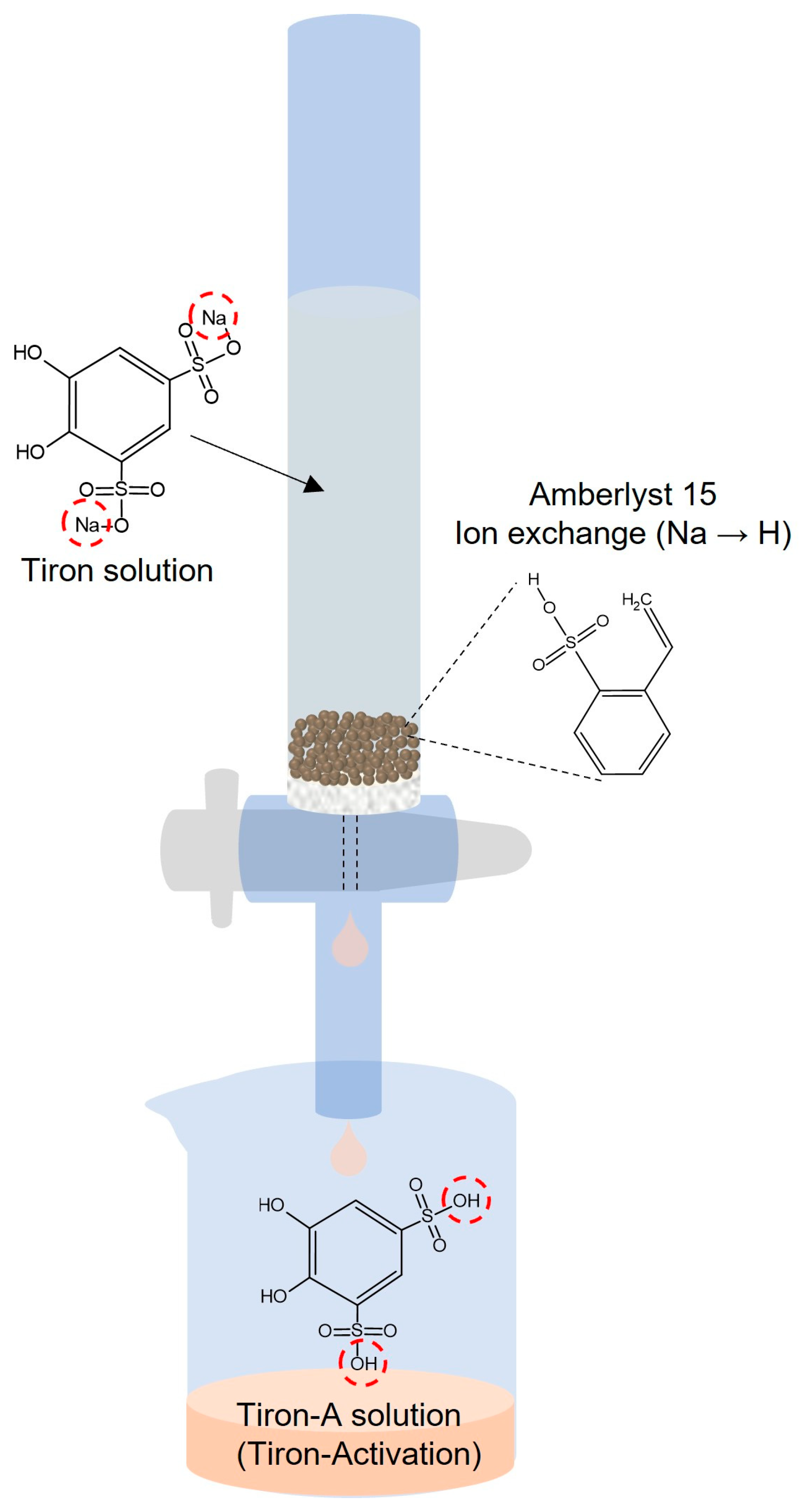

2.2. Preparation

2.3. Electrochemical Analysis

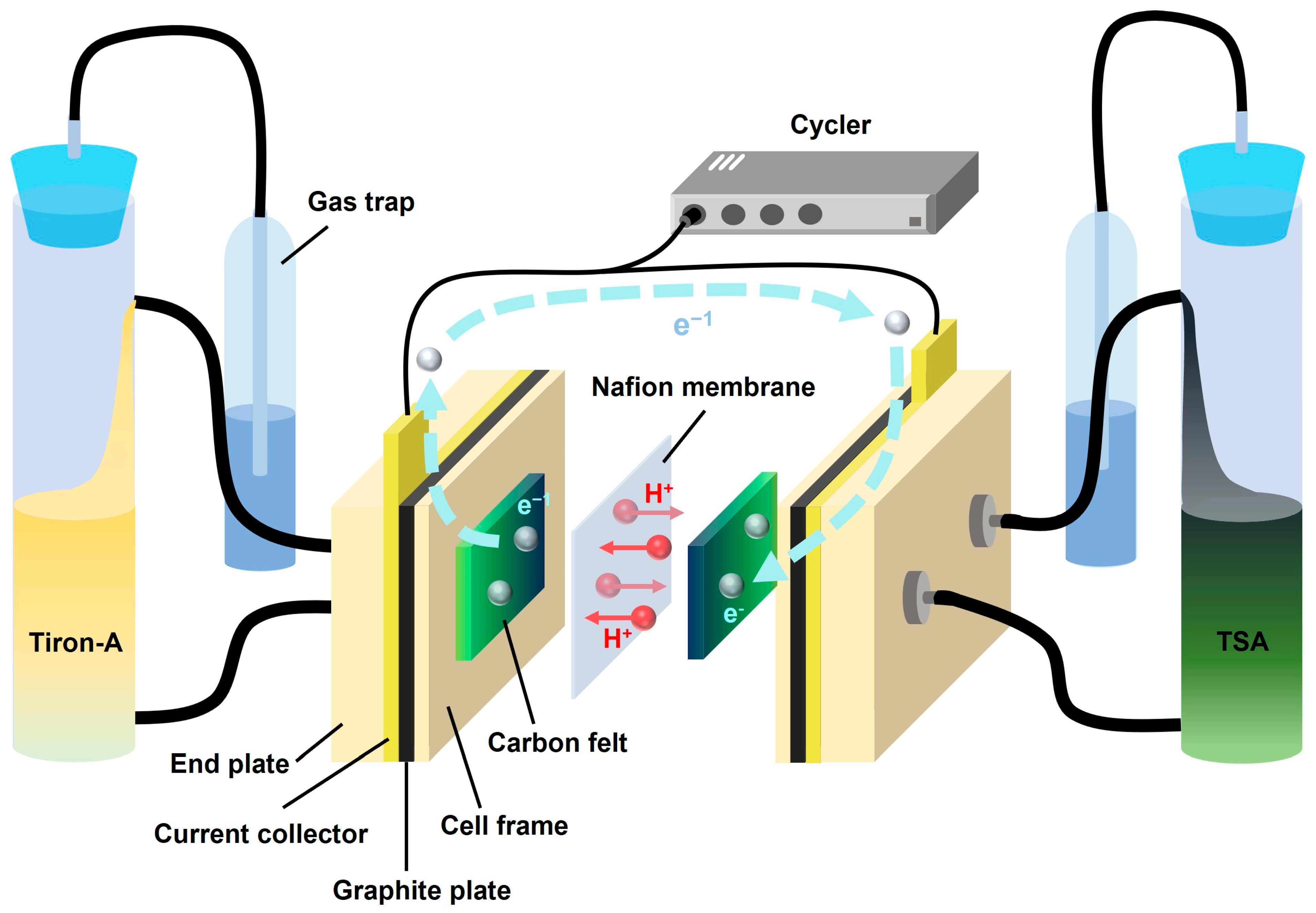

2.4. Battery Performances

3. Results and Discussion

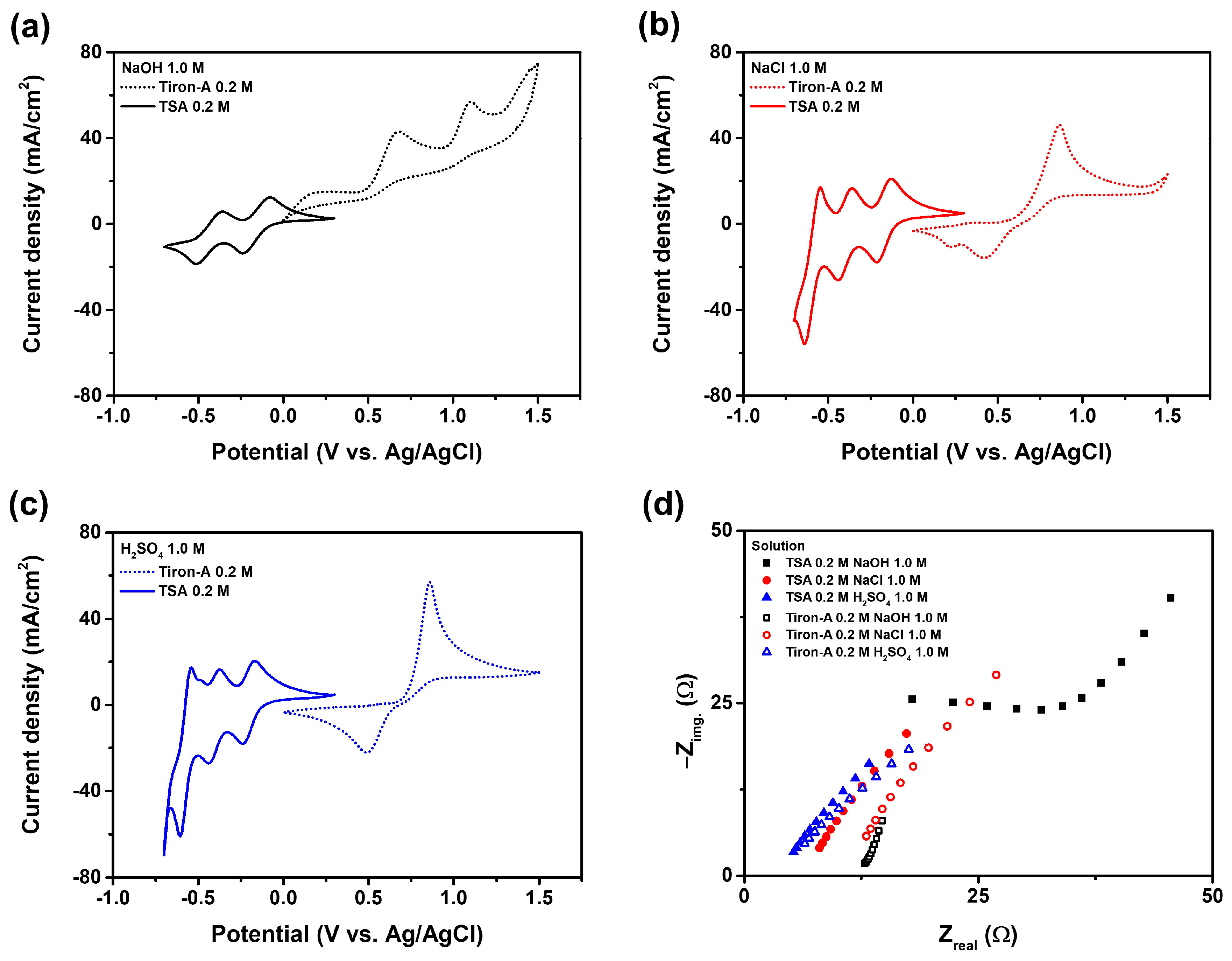

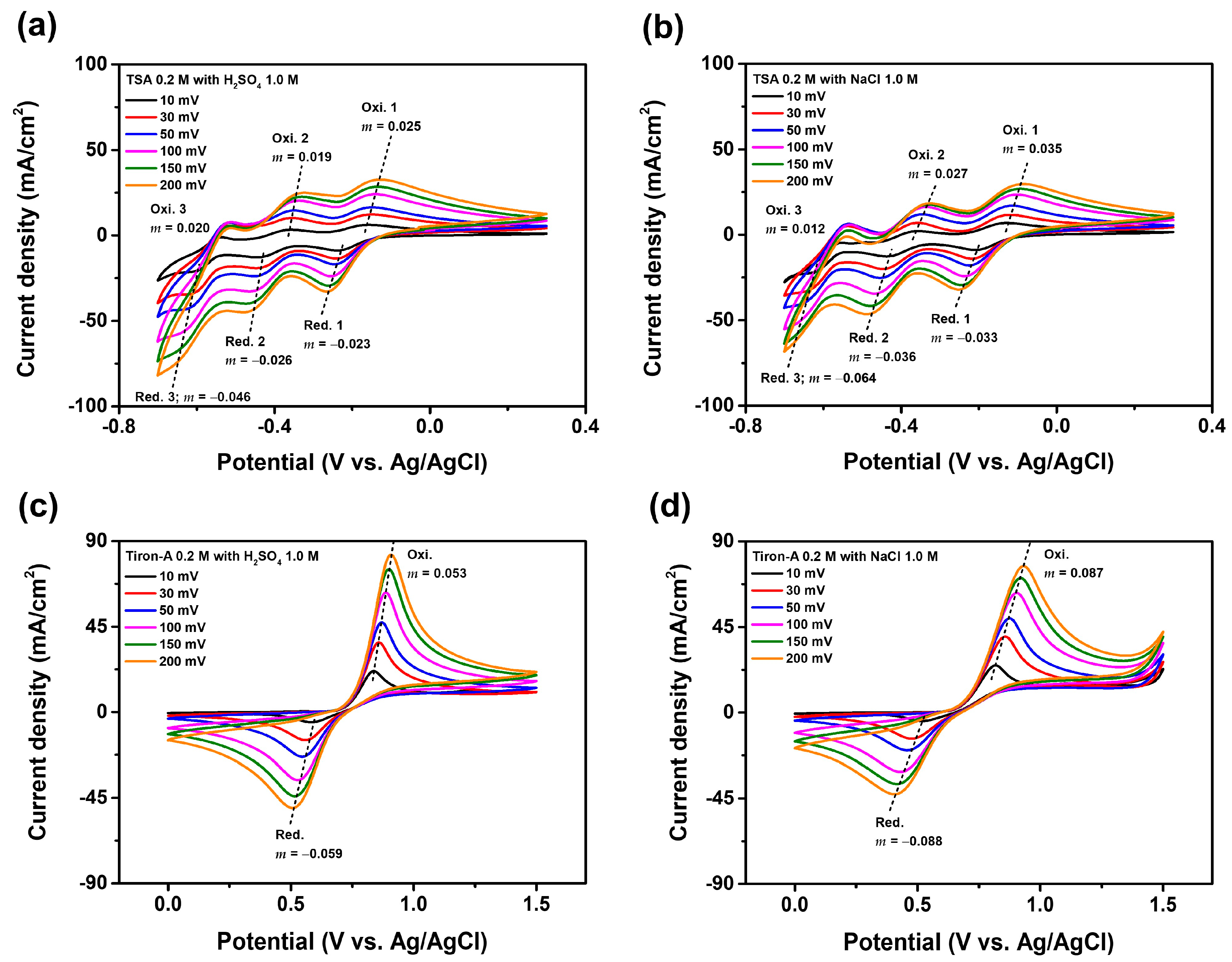

3.1. Supporting Electrolyte

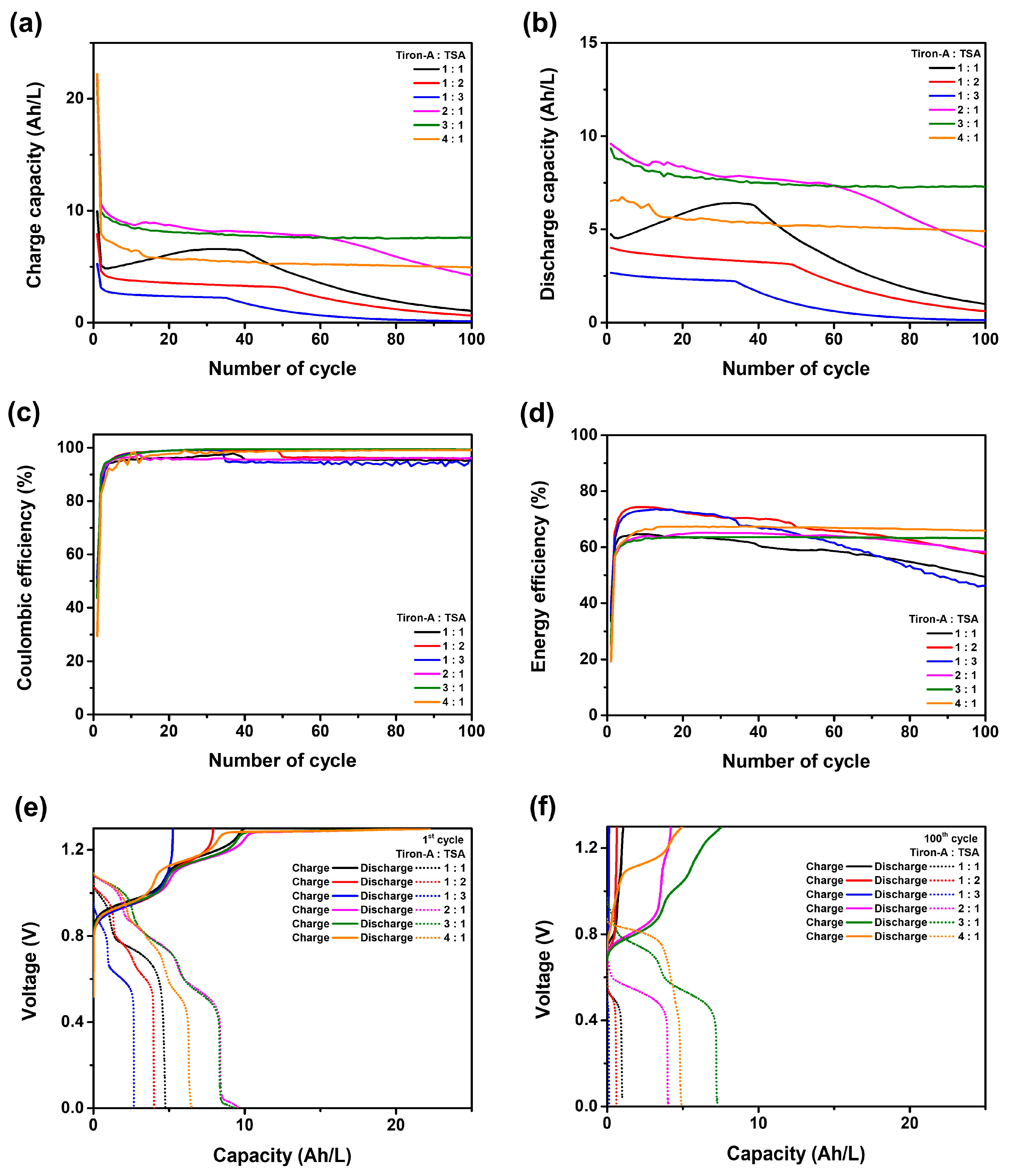

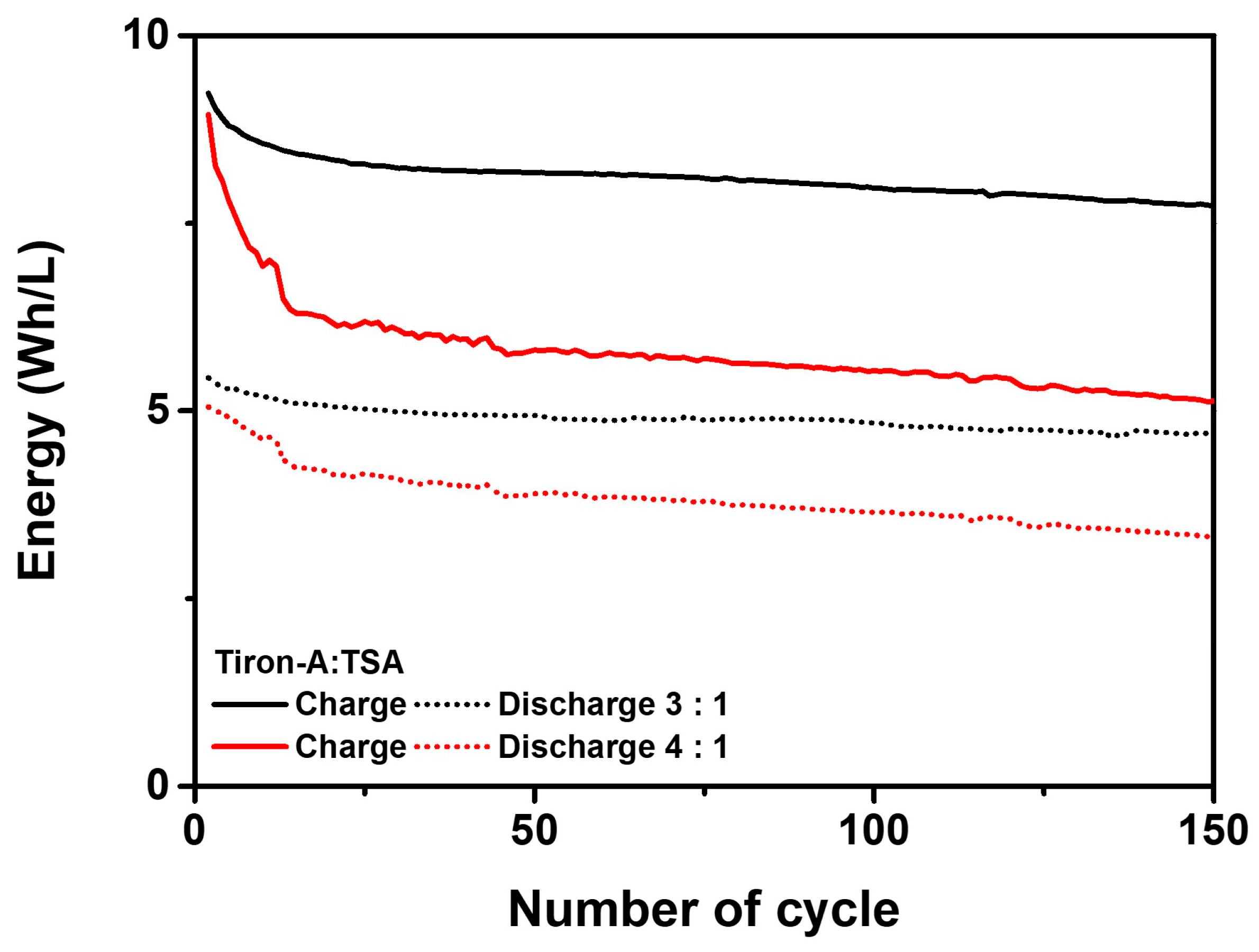

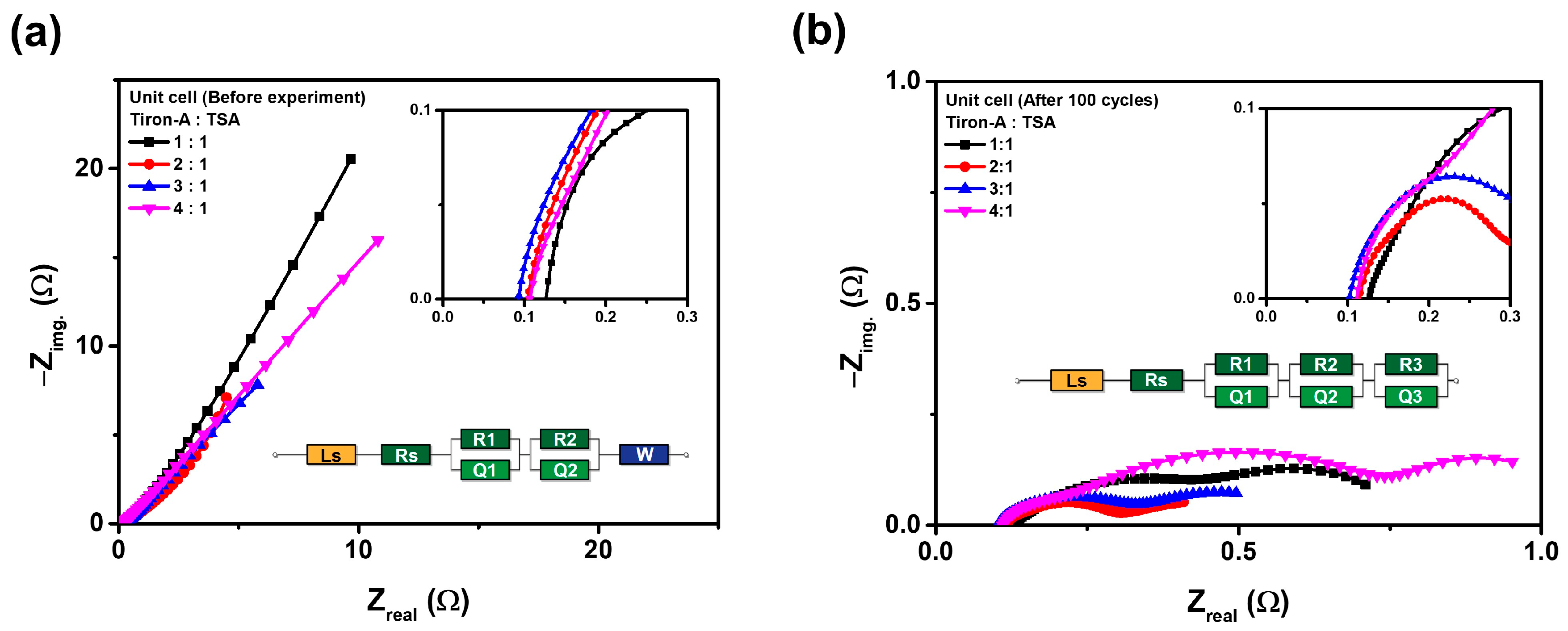

3.2. Cell Performances

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| RFB | Redox flow battery |

| ESS | Energy storage system |

| VRFB | all-vanadium redox flow battery |

| CV | Cyclic voltammetry/cyclic voltammogram |

| EIS | Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy |

| POM | Polyoxometalate |

| TSA | Tungstosilicic acid |

| tiron | disodium 4,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,3-disulfonate |

| tiron-A | 4,5-dihydroxybenzene-1,3-disulfonic acid |

References

- Lu, W.-C. The impacts of information and communication technology, energy consumption, financial development, and economic growth on carbon dioxide emissions in 12 Asian countries. Mitig. Adapt. Strateg. Glob. Change 2018, 23, 1351–1365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Infield, D.; Freris, L. Renewable Energy in Power Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Pedram, M.; Chang, N.; Kim, Y.; Wang, Y. Hybrid electrical energy storage systems. In Proceedings of the 16th ACM/IEEE International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design, San Diego, CA, USA, 21–23 August 2010; pp. 363–368. [Google Scholar]

- Gür, T.M. Review of electrical energy storage technologies, materials and systems: Challenges and prospects for large-scale grid storage. Energy Environ. Sci. 2018, 11, 2696–2767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alotto, P.; Guarnieri, M.; Moro, F. Redox flow batteries for the storage of renewable energy: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2014, 29, 325–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Liu, J. Progress and directions in low-cost redox-flow batteries for large-scale energy storage. Natl. Sci. Rev. 2017, 4, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, R.; Henkensmeier, D.; Yoon, S.J.; Huang, Z.; Kim, D.K.; Chang, Z.; Kim, S.; Chen, R. Redox flow batteries for energy storage: A technology review. J. Electrochem. Energy Convers. Storage 2018, 15, 010801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunha, Á.; Martins, J.; Rodrigues, N.; Brito, F. Vanadium redox flow batteries: A technology review. Int. J. Energy Res. 2015, 39, 889–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, L.; Xi, J.; Wu, Z.; Qiu, X. The benefits and limitations of electrolyte mixing in vanadium flow batteries. Appl. Energy 2017, 204, 373–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poli, N.; Bonaldo, C.; Moretto, M.; Guarnieri, M. Techno-economic assessment of future vanadium flow batteries based on real device/market parameters. Appl. Energy 2024, 362, 122954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Permatasari, A.; Lee, W.; Kwon, Y. Performance improvement by novel activation process effect of aqueous organic redox flow battery using Tiron and anthraquinone-2,7-disulfonic acid redox couple. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 383, 123085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, J.; Li, S.-L.; Su, Z.-M.; Lan, Y.-Q. Polyoxometalate-based materials for sustainable and clean energy conversion and storage. EnergyChem 2019, 1, 100021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwakiri, I.; Antunes, T.; Almeida, H.; Sousa, J.P.; Figueira, R.B.; Mendes, A. Redox flow batteries: Materials, design and prospects. Energies 2021, 14, 5643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumawat, H.; Sharma, S.; Dwivedi, J.; Vivekanand; Neergat, M. Promises and challenges of polyoxometalates (POMs) as an alternative to conventional electrolytes in redox flow batteries (RFBs). Ionics 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, A.; Bao, J.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. Studies on pressure losses and flow rate optimization in vanadium redox flow battery. J. Power Sources 2014, 248, 154–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, B.; Zhao, J.; Su, Y.; Wei, Z.; Skyllas-Kazacos, M. State of charge estimation of vanadium redox flow battery based on sliding mode observer and dynamic model including capacity fading factor. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2017, 8, 1658–1667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakrabarti, B.K.; Kalamaras, E.; Singh, A.K.; Bertei, A.; Rubio-Garcia, J.; Yufit, V.; Tenny, K.M.; Wu, B.; Tariq, F.; Hajimolana, Y.S. Modelling of redox flow battery electrode processes at a range of length scales: A review. Sustain. Energy Fuels 2020, 4, 5433–5468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, D.; Zhao, Y.; Yu, L.; Liu, L.; Xi, J. Asymmetric vanadium flow batteries: Long lifespan via an anolyte overhang strategy. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 29195–29203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Sun, J.; Zheng, M.; Sun, J. Asymmetric supporting electrolyte strategy for electrolyte imbalance mitigation of organic redox flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2024, 101, 113700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Navalpotro, P.; Mavrantonakis, A.; Marcilla, R. Unraveling the role of supporting electrolytes in organic redox flow battery performance. J. Energy Storage 2025, 131, 117570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilonetto, L.F.; Staciaki, F.; Nobrega, E.; Carneiro-Neto, E.B.; da Silva, J.; Pereira, E. Mitigating the capacity loss by crossover transport in vanadium redox flow battery: A chemometric efficient strategy proposed using finite element method simulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 474, 145336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, M.; Gautam, R.K.; Ramani, V.K.; Verma, A. Predicting operational capacity of redox flow battery using a generalized empirical correlation derived from dimensional analysis. Chem. Eng. J. 2020, 379, 122300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Sun, J.; Li, X.; Lin, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Chen, X.; Li, M.; Su, Z.-M. Keggin type polyoxometalate-based metal-organic frameworks with electrocatalytive activity as effective multifunctional amperometric sensors for metal ions and ascorbic acid. J. Mol. Struct. 2025, 1319, 139485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Wen, Y.-H.; Cheng, J.; Cao, G.-P.; Yang, Y.-S. A study of tiron in aqueous solutions for redox flow battery application. Electrochim. Acta 2010, 55, 715–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, J.; Yang, J.J.; Liu, T.; Yuan, R.M.; Deng, D.R.; Zheng, M.S.; Chen, J.J.; Cronin, L.; Dong, Q.F. Tuning redox active polyoxometalates for efficient electron-coupled proton-buffer-mediated water splitting. Chem.–Eur. J. 2019, 25, 11432–11436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karastogianni, S.; Girousi, S.; Sotiropoulos, S. pH: Principles and measurement. Encycl. Food Health 2016, 4, 333–338. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, S.; Li, S.; Du, Y.; Han, X.; Xu, P. How to reliably report the overpotential of an electrocatalyst. ACS Energy Lett. 2020, 5, 1083–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopkins, A. Electromotive Forces; Scientific e-Resources: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Santana, J.; Espinoza-Andaluz, M.; Li, T.; Andersson, M. A detailed analysis of internal resistance of a PEFC comparing high and low humidification of the reactant gases. Front. Energy Res. 2020, 8, 572333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hambly, B.P.; Sheppard, J.B.; Pendley, B.D.; Lindner, E. Voltammetric determination of diffusion coefficients in polymer membranes: Guidelines to minimize errors. Electroanalysis 2018, 30, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frenzel, N.; Hartley, J.; Frisch, G. Voltammetric and spectroscopic study of ferrocene and hexacyanoferrate and the suitability of their redox couples as internal standards in ionic liquids. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 28841–28852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masood, Z.; Muhammad, H.; Tahiri, I.A. Comparison of different electrochemical methodologies for electrode reactions: A case study of paracetamol. Electrochem 2024, 5, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sankaralingam, R.K.; Seshadri, S.; Sunarso, J.; Bhatt, A.I.; Kapoor, A. Overview of the factors affecting the performance of vanadium redox flow batteries. J. Energy Storage 2021, 41, 102857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoni, F.; De Angelis, A.; Moschitta, A.; Carbone, P.; Galeotti, M.; Cinà, L.; Giammanco, C.; Di Carlo, A. A guide to equivalent circuit fitting for impedance analysis and battery state estimation. J. Energy Storage 2024, 82, 110389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Yu, M.; Peng, Y.; Ran, F. Electrolyte-wettability issues and challenges of electrode materials in electrochemical energy storage, energy conversion, and beyond. Adv. Sci. 2023, 10, 2300283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Reaction | Potential (V vs. RHE) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NaCl 1.0 M Electrolyte | H2SO4 1.0 M Electrolyte | |||

| Oxidation | Reduction | Oxidation | Reduction | |

| H(SiW12O40)3− + e− + H+ ↔ H2(SiW12O40)2− | 0.072 | −0.014 | 0.014 | −0.057 |

| H2(SiW12O40)2− + e− + H+ ↔ H3(SiW12O40)− | −0.162 | −0.244 | −0.190 | −0.255 |

| H3(SiW12O40)− + e− + H+ ↔ H4(SiW12O40) | −0.349 | −0.442 | −0.358 | −0.423 |

| (O)22−C6H2(HSO3)2 + 2e− + 2H+ ↔ (OH)2C6H2(HSO3)2 | 1.099 | 0.649 | 1.055 | 0.682 |

| Supporting Electrolyte | pH | |

|---|---|---|

| TSA (0.2 M) | Tiron-A (0.2 M) | |

| NaOH 1.0 M | 4.63 | 13.5 |

| NaCl 1.0 M | −0.01 | 0.58 |

| H2SO4 1.0 M | −0.27 | −0.07 |

| Electrolytes | Diffusion Coefficient (10−9 cm2/s) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxi. 1 | Oxi. 2 | Oxi. 3 | Red. 1 | Red. 2 | Red. 3 | |

| TSA 0.2 M with H2SO4 1.0 M | 2.01 | 1.25 | Non-diffusion | 1.73 | 3.01 | 8.93 |

| TSA 0.2 M with NaCl 1.0 M | 1.55 | 0.80 | Non-diffusion | 1.60 | 3.32 | 6.52 |

| Tiron-A 0.2 M with H2SO4 1.0 M | 1.35 | - | - | 0.74 | - | - |

| Tiron-A 0.2 M with NaCl 1.0 M | 0.95 | - | - | 0.53 | - | - |

| Parameter | Tiron-A:TSA | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pristine Unit Cell (Ω) | Post-Cycled Unit Cell (Ω) | |||||||

| 1:1 | 2:1 | 3:1 | 4:1 | 1:1 | 2:1 | 3:1 | 4:1 | |

| Rs | 0.11 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.10 |

| R1 | 0.11 | 58.33 | 165.33 | 0.12 | 0.29 | 0.14 | 0.22 | 0.39 |

| Q1 | 0.88 | 2.11 | 0.82 | 0.70 | 2.76 | 0.76 | 0.67 | 0.73 |

| R2 | 1643.75 | 0.25 | 0.36 | 3553.54 | 0.16 | 0.04 | 0.25 | 0.28 |

| Q2 | 0.94 | 0.68 | 0.64 | 0.70 | 2.19 | 0.83 | 3.78 | 5.27 |

| R3 | - | - | - | - | 0.28 | 0.36 | 0.06 | 0.11 |

| Q3 | - | - | - | - | 0.81 | 5.94 | 0.87 | 0.70 |

| W | 0.16 | 0.18 | 1.02 | 1.76 | - | - | - | - |

| Total | 1645.95 | 61.63 | 168.24 | 3556.91 | 6.60 | 8.17 | 5.93 | 7.58 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cho, Y.J.; Jeong, J.-H.; Kwon, B.W. Optimizing Volumetric Ratio and Supporting Electrolyte of Tiron-A/Tungstosilicic Acid Derived Redox Flow Battery. Materials 2025, 18, 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18194614

Cho YJ, Jeong J-H, Kwon BW. Optimizing Volumetric Ratio and Supporting Electrolyte of Tiron-A/Tungstosilicic Acid Derived Redox Flow Battery. Materials. 2025; 18(19):4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18194614

Chicago/Turabian StyleCho, Yong Jin, Jun-Hee Jeong, and Byeong Wan Kwon. 2025. "Optimizing Volumetric Ratio and Supporting Electrolyte of Tiron-A/Tungstosilicic Acid Derived Redox Flow Battery" Materials 18, no. 19: 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18194614

APA StyleCho, Y. J., Jeong, J.-H., & Kwon, B. W. (2025). Optimizing Volumetric Ratio and Supporting Electrolyte of Tiron-A/Tungstosilicic Acid Derived Redox Flow Battery. Materials, 18(19), 4614. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma18194614