Concept of Sustainable Demolition Process for Brickwork Buildings with Expanded Polystyrene Foam Insulation Using Mealworms of Tenebrio molitor

Abstract

1. Introduction

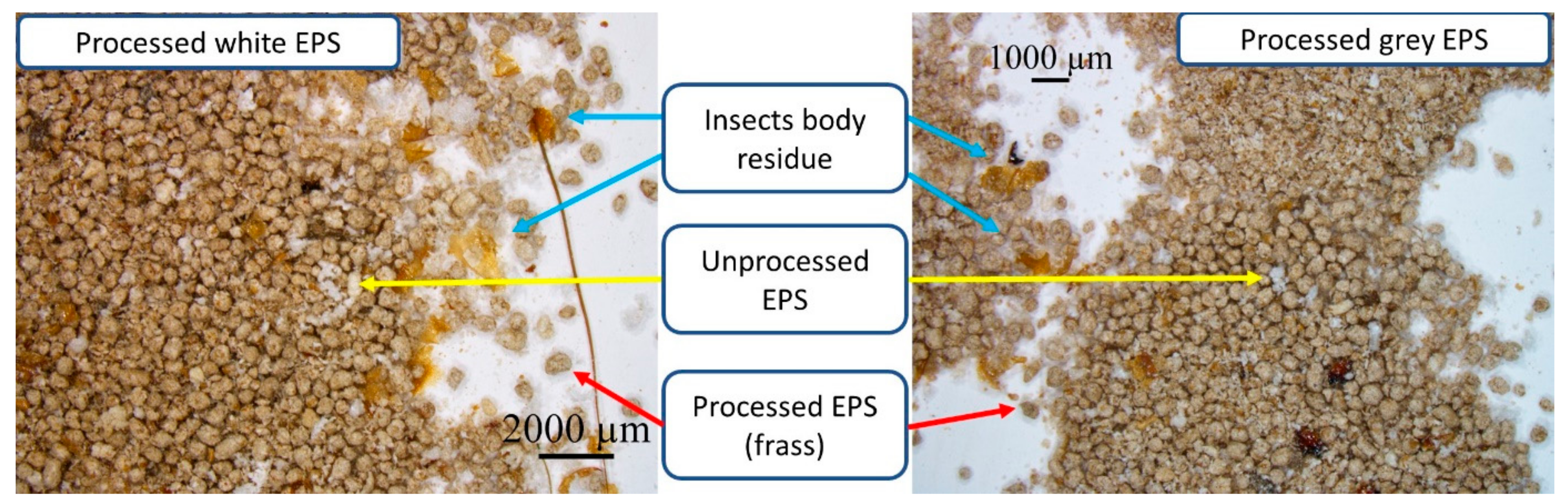

2. Materials and Methods

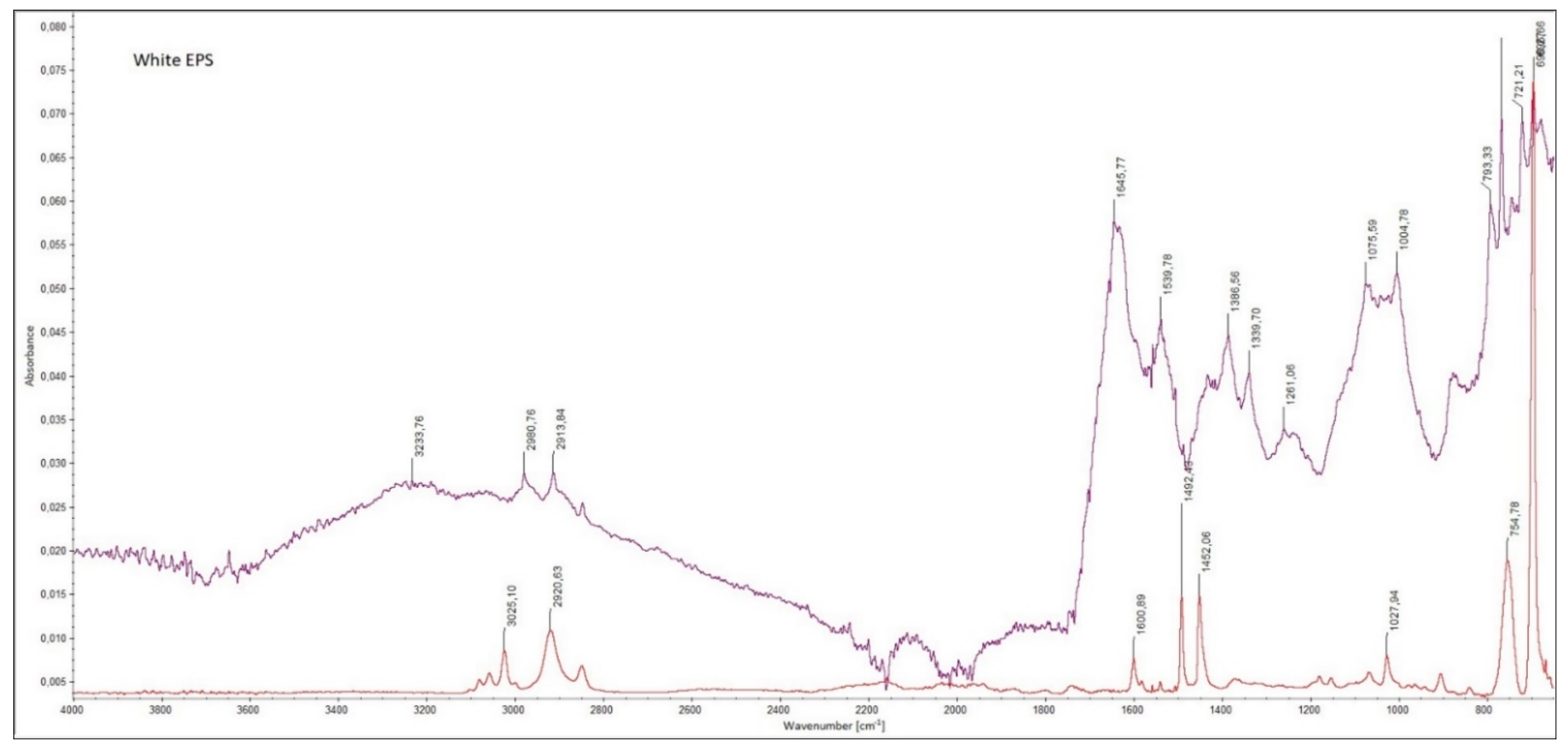

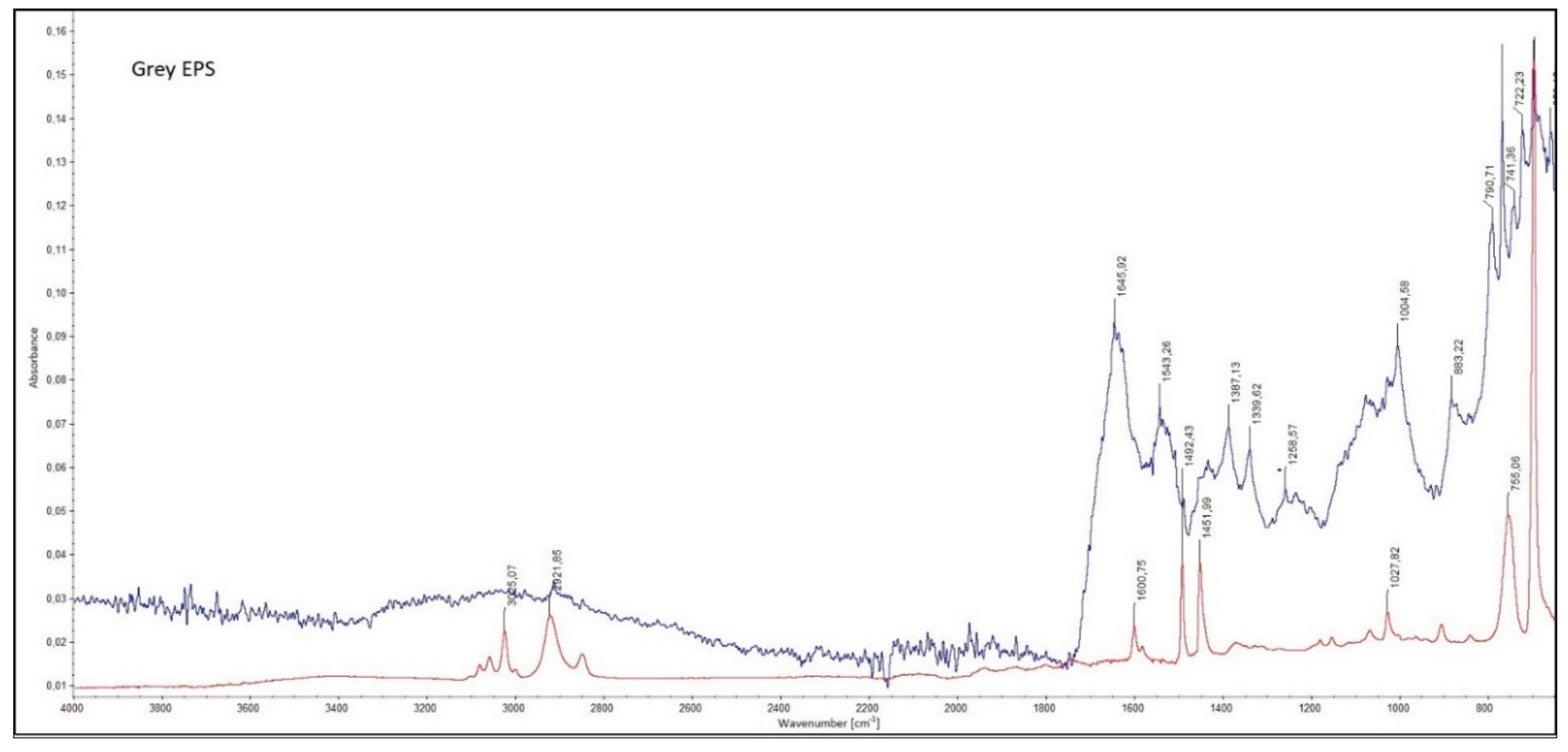

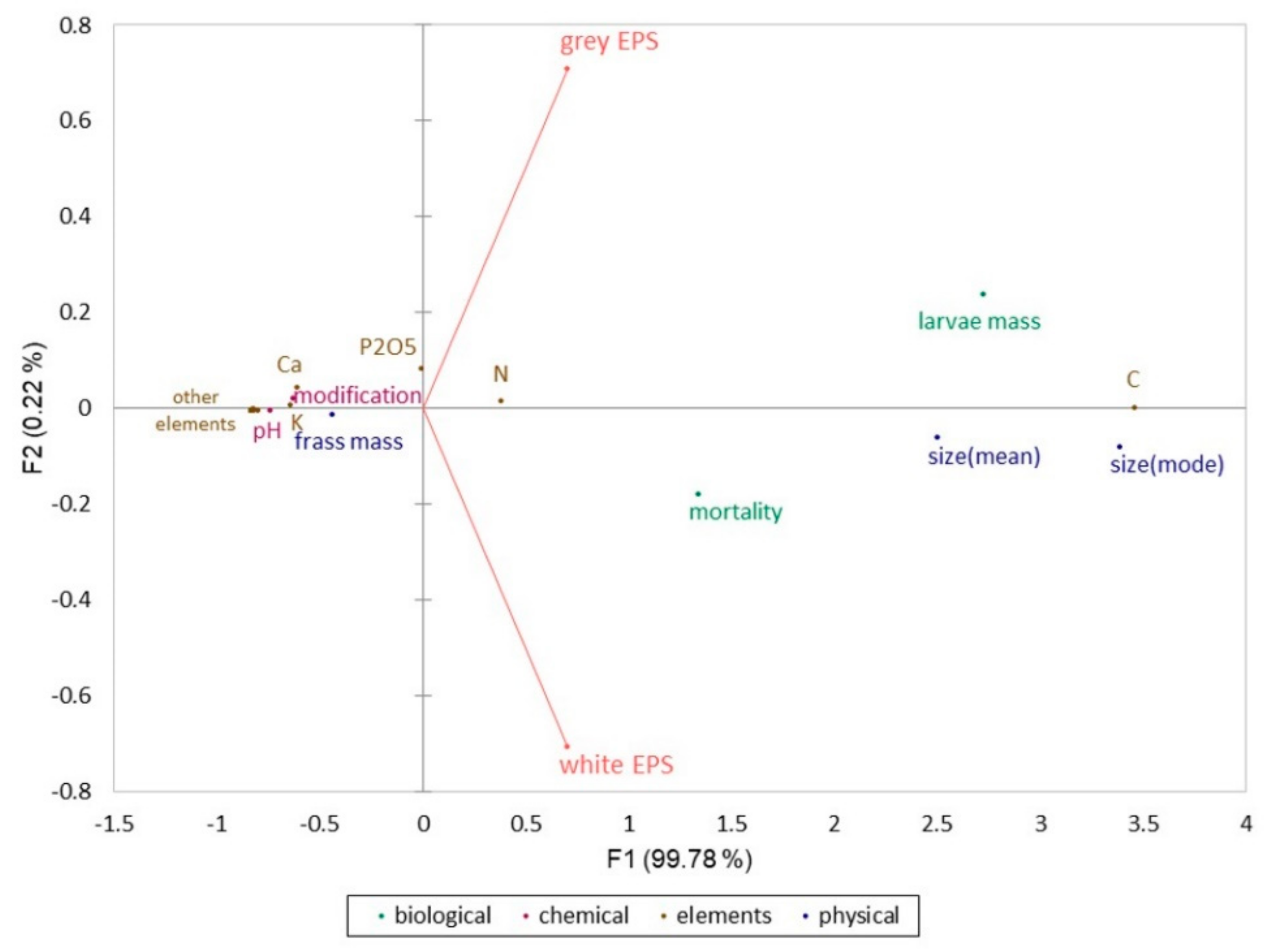

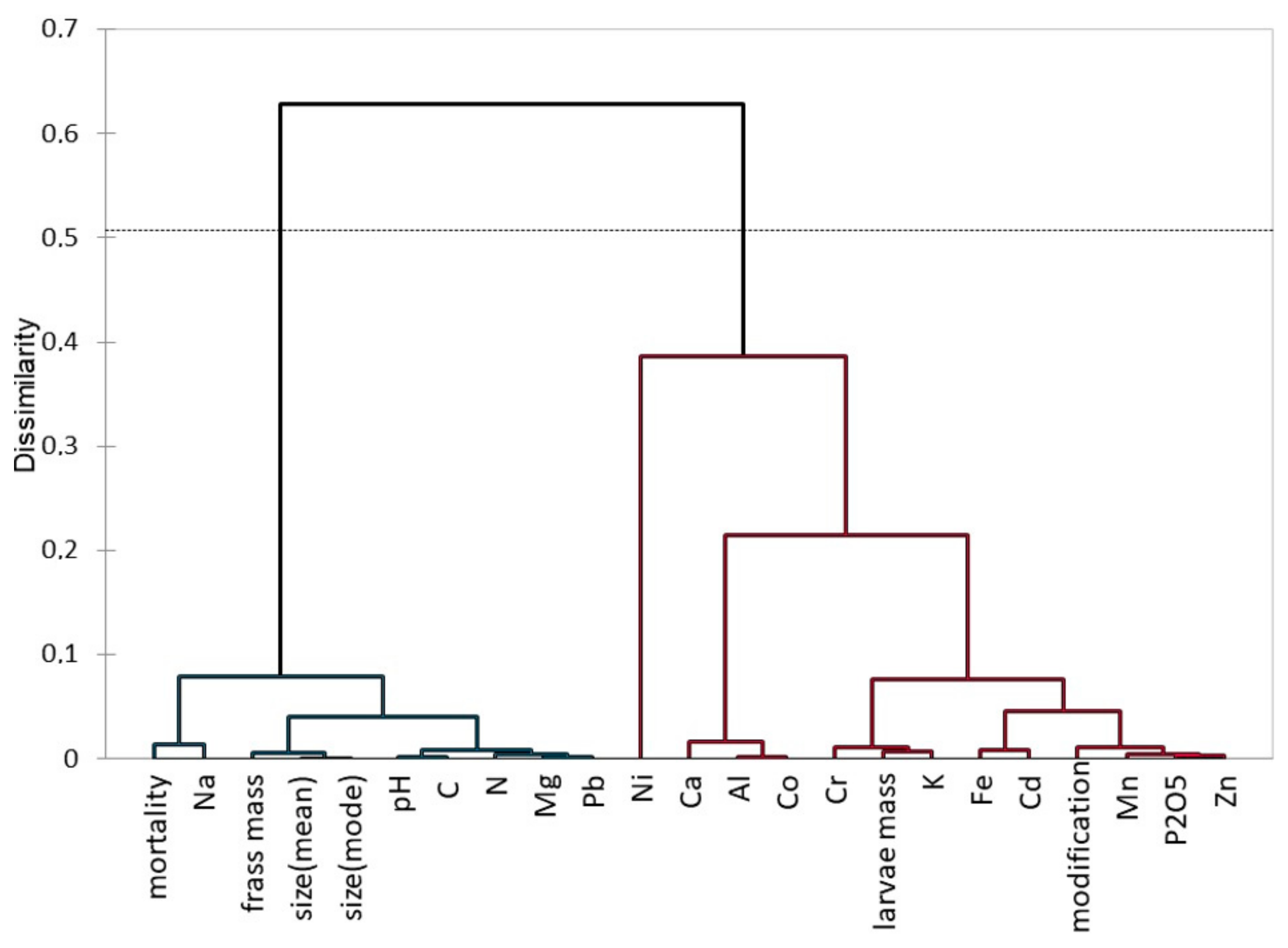

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

- It is feasible to clean brickwork debris from EPS using Tenebrio molitor larvae.

- The process of cleaning brickwork using Tenebrio molitor larvae is faster in the case of grey EPS, in comparison to white EPS.

- There are no new harmful or toxic organic residues in the frass. Therefore, the proposed biodegradation process for EPS should be considered as safe.

- More research is needed to scale the process and to find the best method for using frass.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- European Commission. Construction and Demolition Waste—Environment. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/environment/waste/construction_demolition.htm (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Gálvez-Martos, J.-L.; Styles, D.; Schoenberger, H.; Zeschmar-Lahl, B. Construction and demolition waste best management practice in Europe. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2018, 136, 166–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on Waste and Repealing Certain Directives. 2008. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/HTML/?uri=CELEX:32008L0098&from=EN (accessed on 4 March 2021).

- Zerowasteeurope.eu. Zero Waste Masterplan—Turning the Vision of Circular Economy into a Reality in Europe; Zerowasteeurope.eu: Brussels, Belgium, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ginga, C.P.; Ongpeng, J.M.C.; Daly, M.K.M. Circular economy on construction and demolition waste: A literature review on material recovery and production. Materials 2020, 13, 2970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Horňáková, M.; Lehner, P.; Le, T.D.; Konečný, P.; Katzer, J. Durability characteristics of concrete mixture based on red ceramic waste aggregate. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz, Z.; Mostofinejad, D. Porcelain and red ceramic wastes used as replacements for coarse aggregate in concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 2019, 195, 218–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hornakova, M.; Katzer, J.; Kobaka, J.; Konecny, P. Lightweight SFRC benefitting from a pre-soaking and internal curing process. Materials 2019, 12, 4152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Halbiniak, J.; Katzer, J.; Major, M.; Major, I. A proposition of an in situ production of a blended cement. Materials 2020, 13, 2289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.S.; Wu, W.M.; Brandon, A.M.; Fan, H.Q.; Receveur, J.P.; Li, Y.; Wang, Z.Y.; Fan, R.; McClellan, R.L.; Gao, S.H.; et al. Ubiquity of polystyrene digestion and biodegradation within yellow mealworms, larvae of Tenebrio molitor Linnaeus (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Chemosphere 2018, 212, 262–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nukmal, N.; Umar, S.; Amanda, S.P.; Kanedi, M. Effect of styrofoam waste feeds on the growth, development and fecundity of mealworms (Tenebrio molitor). J. Biol. Sci. 2018, 18, 24–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siemianowska, E.; Kosewska, A.; Aljewicz, M.; Skibniewska, K.; Polak-Jaszczuk, L.; Jarocki, A.; Jędras, M. Larvae od mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) as European novel food. Agric. Sci. 2013, 4, 287–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przemieniecki, S.W.; Kosewska, A.; Ciesielski, S.; Kosewska, O. Changes in the gut microbiome and enzymatic profile of Tenebrio molitor larvae biodegrading cellulose, polyethylene and polystyrene waste. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 256, 113265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pivato, A.F.; Miranda, G.M.; Prichula, J.; Lima, J.E.A.; Ligabue, R.A.; Seixas, A.; Trentin, D.S. Hydrocarbon-based plastics: Progress and perspectives on consumption and biodegradation by insect larvae. Chemosphere 2022, 293, 133600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, B.Y.; Su, Y.; Chen, Z.; Chen, J.; Zhou, X.; Benbow, M.E.; Criddle, C.S.; Wu, W.M.; Zhang, Y. Biodegradation of Polystyrene by Dark (Tenebrio obscurus) and Yellow (Tenebrio molitor) Mealworms (Coleoptera: Tenebrionidae). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 5256–5265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneron, A.; Jehan, C.; Rigaud, T.; Moret, Y. Immune defenses of a beneficial pest: The mealworm beetle, Tenebrio molitor. Front. Physiol. 2019, 10, 138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hassan, M.W.; Ali, U.; Ur Rehman, F.; Najeeb, H.; Sohail, M.; Irsa, B.; Muzaffar, Z.; Chaudhry, M.S. Evaluation of standard loose plastic packaging for the management of Rhyzopertha dominica (F.) (Coleoptera: Bostrichidae) and Tribolium castaneum (Herbst) (Coleoptera: Tenebriondiae). J. Insect Sci. 2016, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Wu, W.; Zhao, J.; Song, Y.; Gao, L.; Yang, R.; Jiang, L. Biodegradation and mineralization of polystyrene by plastic-eating mealworms: Part 1. Chemical and physical characterization and isotopic tests. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2015, 49, 12080–12086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urbanek, A.K.; Rybak, J.; Wróbel, M.; Leluk, K.; Mirończuk, A.M. A comprehensive assessment of microbiome diversity in Tenebrio molitor fed with polystyrene waste. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 262, 114281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehner, P.; Konečný, P.; Katzer, J. Electrical resistivity and strength parameters of prismatic mortar samples based on standardized sand and lunar aggregate simulant. Buildings 2022, 12, 423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, G.B.J.; de Weerd, C.; Thoenes, D.; Goossens, H.W.J. Laser diffraction spectrometry: Fraunhofer diffraction versus Mie scattering. Part. Charact. 1987, 4, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobaka, J. A statistical model of fibre distribution in a steel fibre reinforced concrete. Materials 2021, 14, 7297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Addinsoft. XLSTAT Statistical and Data Analysis Solution; Addinsoft: Long Island City, NY, USA, 2021; Available online: https://www.xlstat.com (accessed on 20 April 2022).

- Gałęcki, R.; Zielonka, Ł.; Zasępa, M.; Gołębiowska, J.; Bakuła, T. Potential utilization of edible insects as an alternative source of protein in animal diets in Poland. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2021, 5, 675796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przemieniecki, S.W.; Kosewska, A.; Purwin, S.; Zapałowska, A.; Mastalerz, J.; Kotlarz, K.; Kolaczek, K. Biometric, chemical, and microbiological evaluation of common wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) seedlings fertilized with mealworm (Tenebrio molitor L.) larvae meal. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2021, 167, 104037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, I. Fifty Materials That Make the World; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany; Dartmouth College: Hanover, NH, USA, 2018; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

| Type of EPS | Apparent Density [kg/m3] | Volume of Used Specimen [cm3] |

|---|---|---|

| Ordinary—white | 24.31 ± 0.50 | 160.0 ± 5 |

| With addition of graphite—grey | 19.66 ± 0.50 | 160.0 ± 5 |

| Observation | Unit | White EPS | Grey EPS |

|---|---|---|---|

| Larvae mass | [g] | 292.89 | 327.81 |

| Mortality | [g] | 207.11 | 172.19 |

| Frass mass | [g] | 35.61 | 33.01 |

| Mean size | [µm] | 299.7 | 282.7 |

| Mode size | [µm] | 379.3 | 357.1 |

| Standard deviation | [µm] | 20.09 | 33.26 |

| Compound | White EPS | Grey EPS |

|---|---|---|

| P2O5 | 0.655 | 0.791 |

| N | 105.900 | 106.500 |

| C | 378.800 | 371.000 |

| Ca | 15.643 | 23.327 |

| Mg | 2.981 | 2.9644 |

| K | 16.177 | 17.618 |

| Na | 1.365 | 1.198 |

| Fe | 0.547 | 0.739 |

| Al | 0.922 | 1.443 |

| Mn | 0.046 | 0.056 |

| B | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Co | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Ni | 0.000 | 0.002 |

| Cu | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Zn | 0.088 | 0.105 |

| Cr | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| Cd | 0.000 | 0.000 |

| Pb | 0.006 | 0.006 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Przemieniecki, S.W.; Katzer, J.; Kosewska, A.; Kosewska, O.; Sowiński, P.; Żeliszewska, P.; Kalisz, B. Concept of Sustainable Demolition Process for Brickwork Buildings with Expanded Polystyrene Foam Insulation Using Mealworms of Tenebrio molitor. Materials 2022, 15, 7516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217516

Przemieniecki SW, Katzer J, Kosewska A, Kosewska O, Sowiński P, Żeliszewska P, Kalisz B. Concept of Sustainable Demolition Process for Brickwork Buildings with Expanded Polystyrene Foam Insulation Using Mealworms of Tenebrio molitor. Materials. 2022; 15(21):7516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217516

Chicago/Turabian StylePrzemieniecki, Sebastian W., Jacek Katzer, Agnieszka Kosewska, Olga Kosewska, Paweł Sowiński, Paulina Żeliszewska, and Barbara Kalisz. 2022. "Concept of Sustainable Demolition Process for Brickwork Buildings with Expanded Polystyrene Foam Insulation Using Mealworms of Tenebrio molitor" Materials 15, no. 21: 7516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217516

APA StylePrzemieniecki, S. W., Katzer, J., Kosewska, A., Kosewska, O., Sowiński, P., Żeliszewska, P., & Kalisz, B. (2022). Concept of Sustainable Demolition Process for Brickwork Buildings with Expanded Polystyrene Foam Insulation Using Mealworms of Tenebrio molitor. Materials, 15(21), 7516. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma15217516