Hydrogen vs. Halogen Bonds in 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Computational Methods

3. Results and Discussions

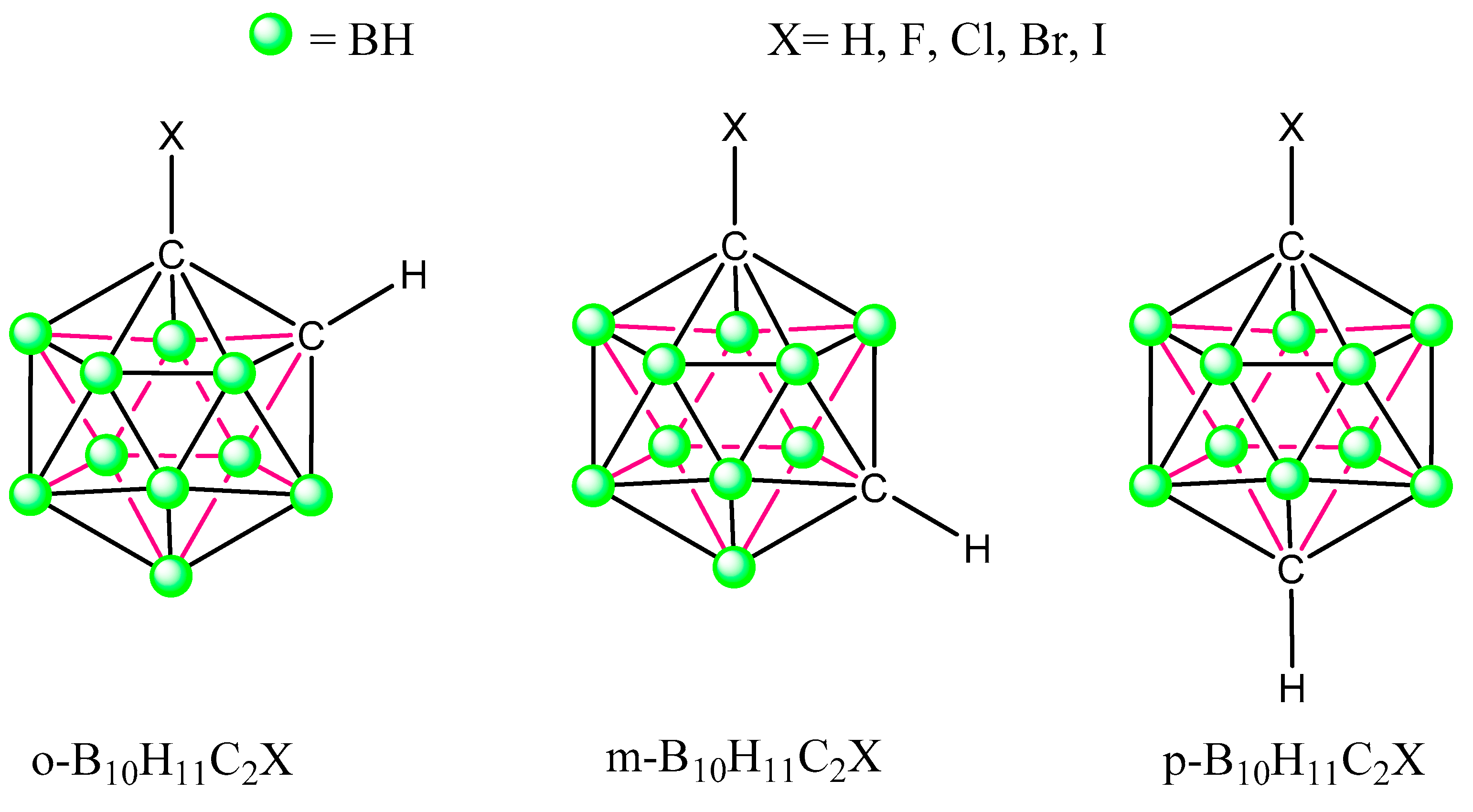

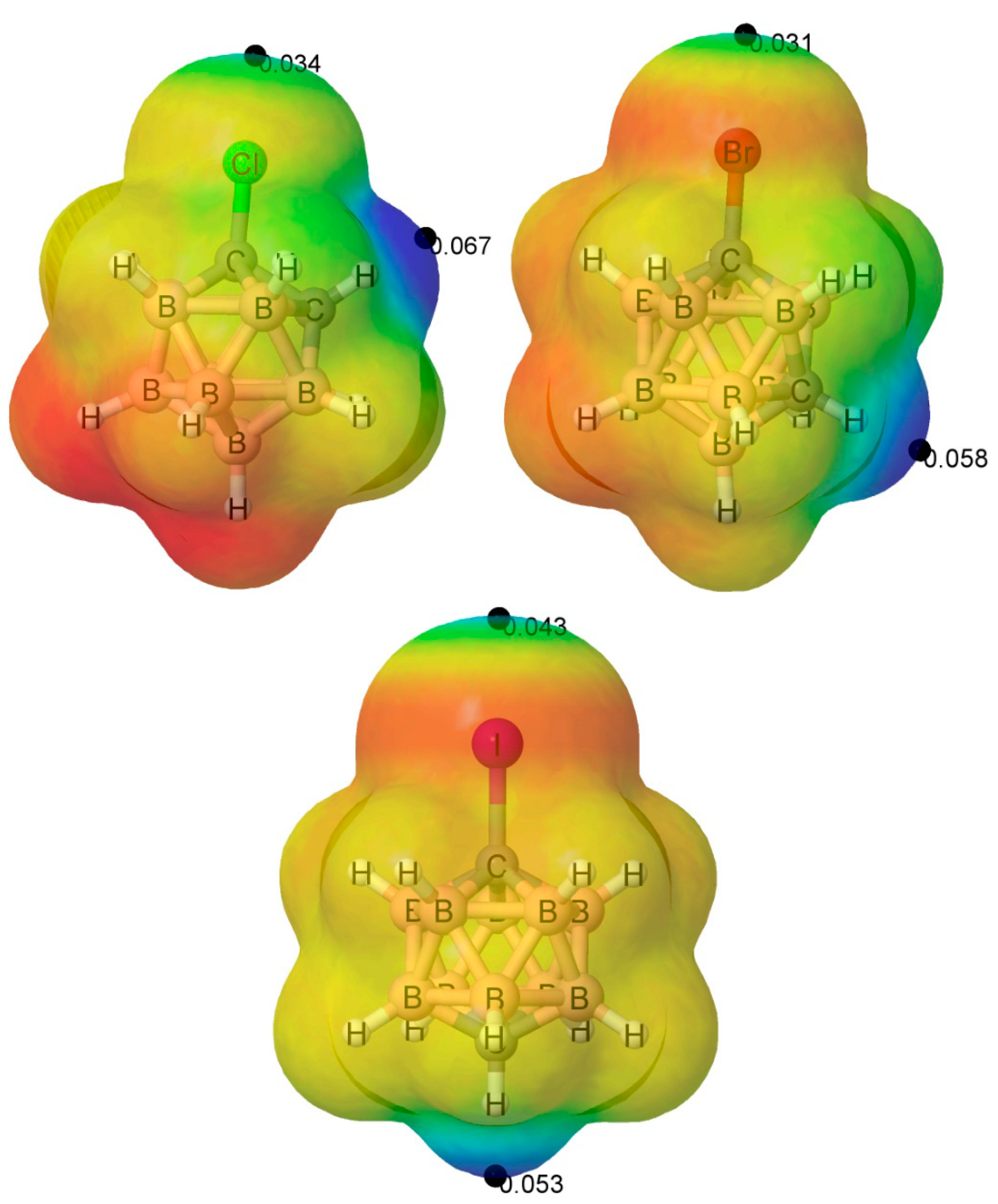

3.1. Isolated 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes

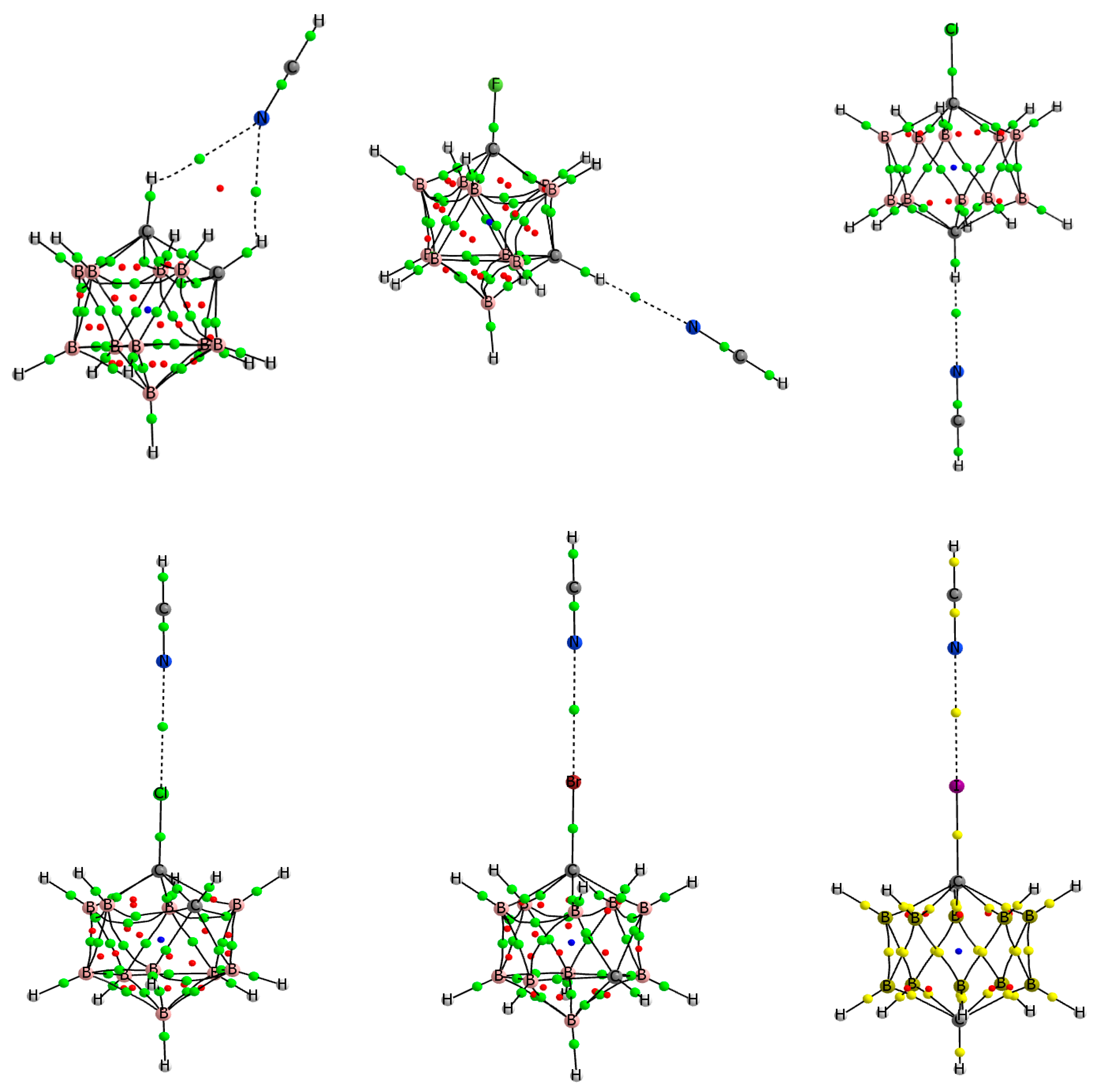

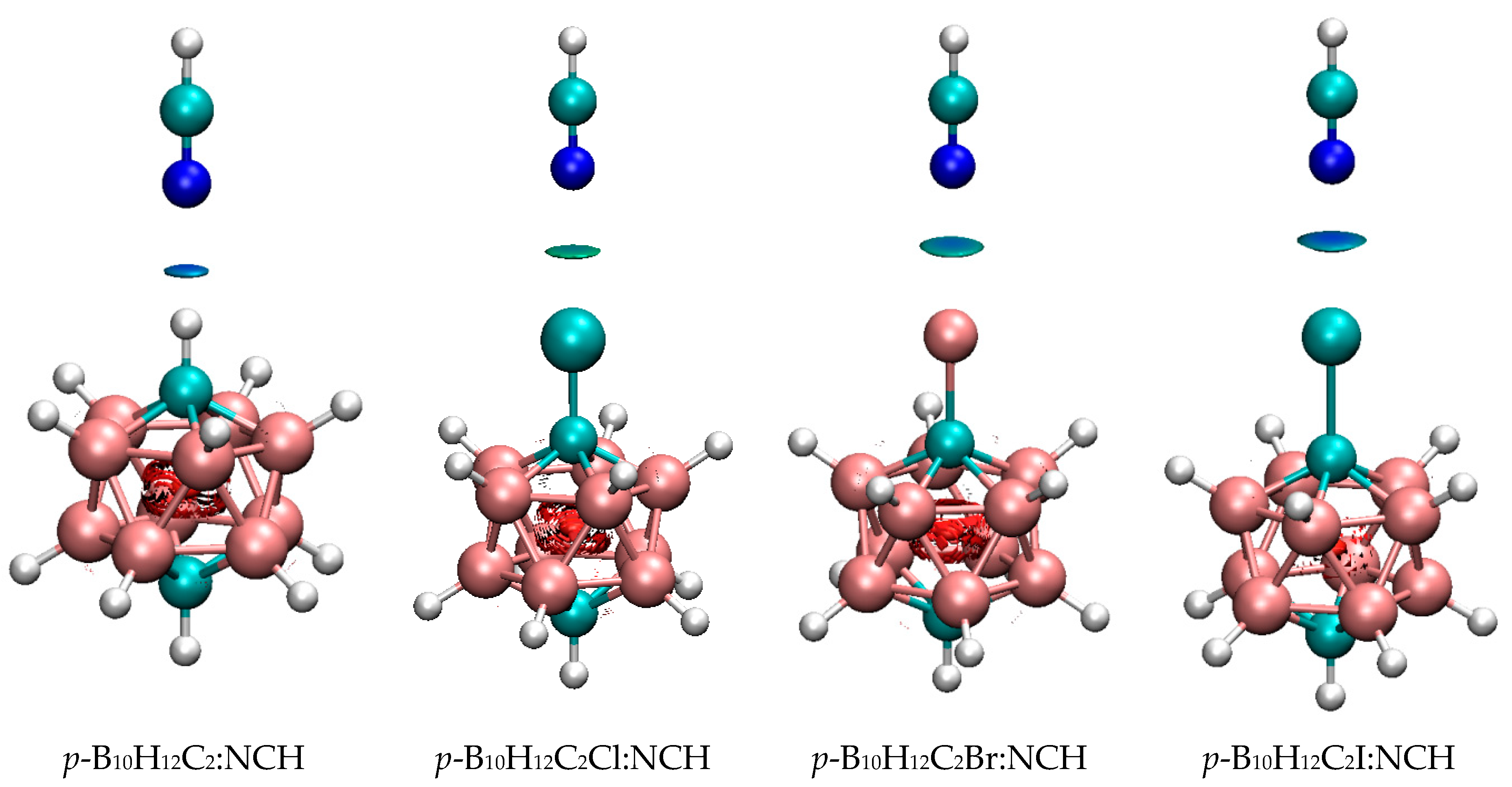

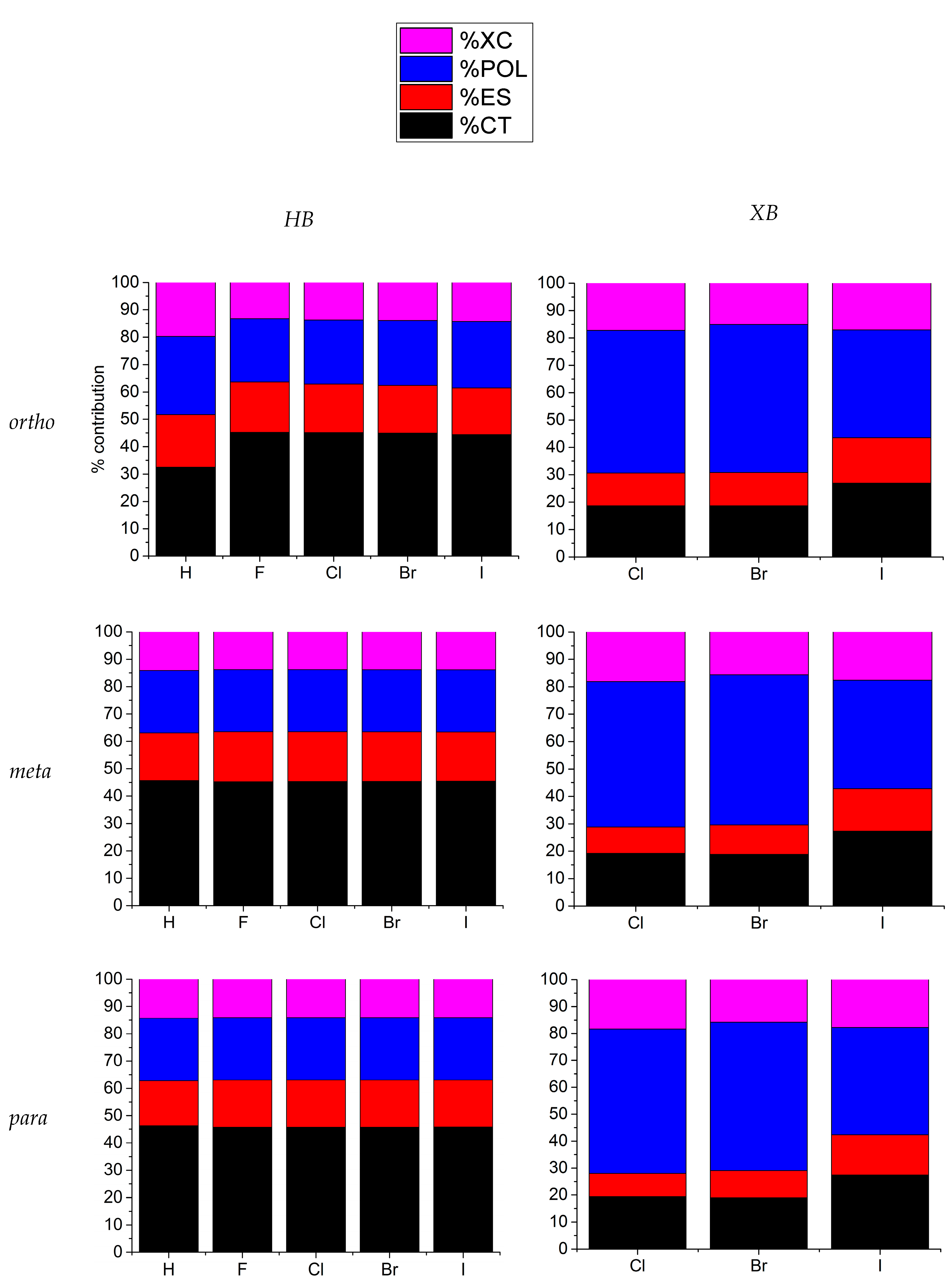

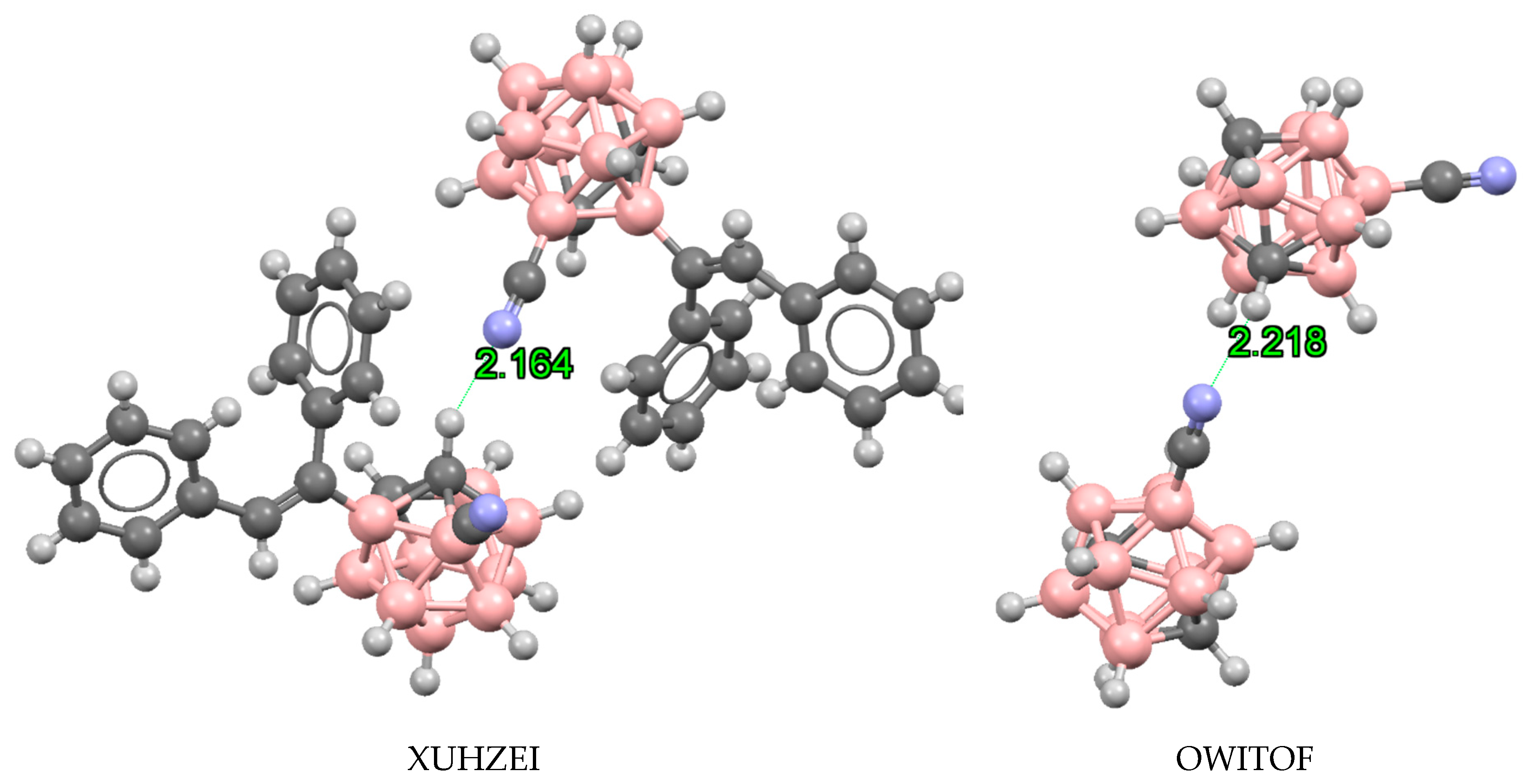

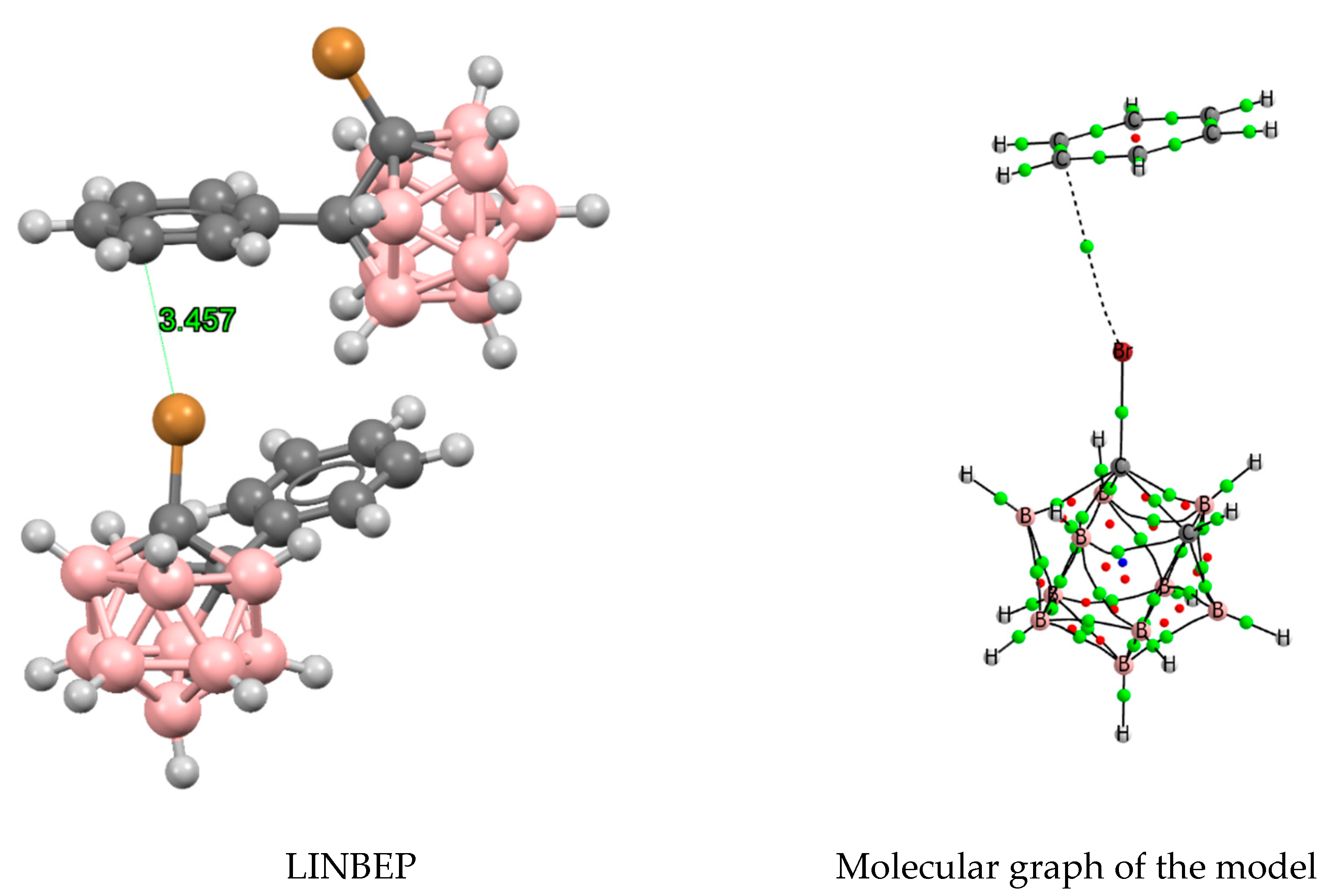

3.2. 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes in Hydrogen and Halogen Bonds

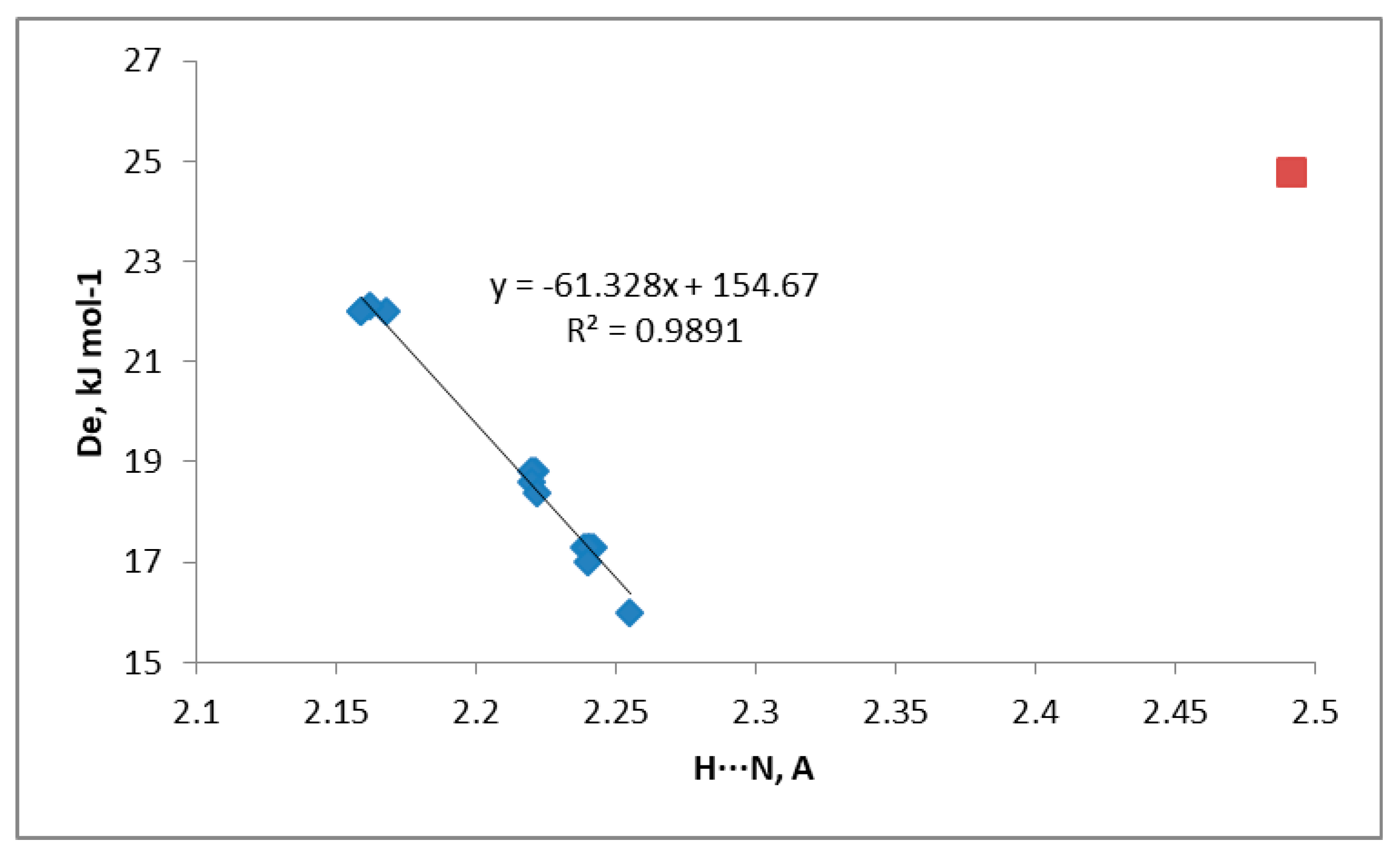

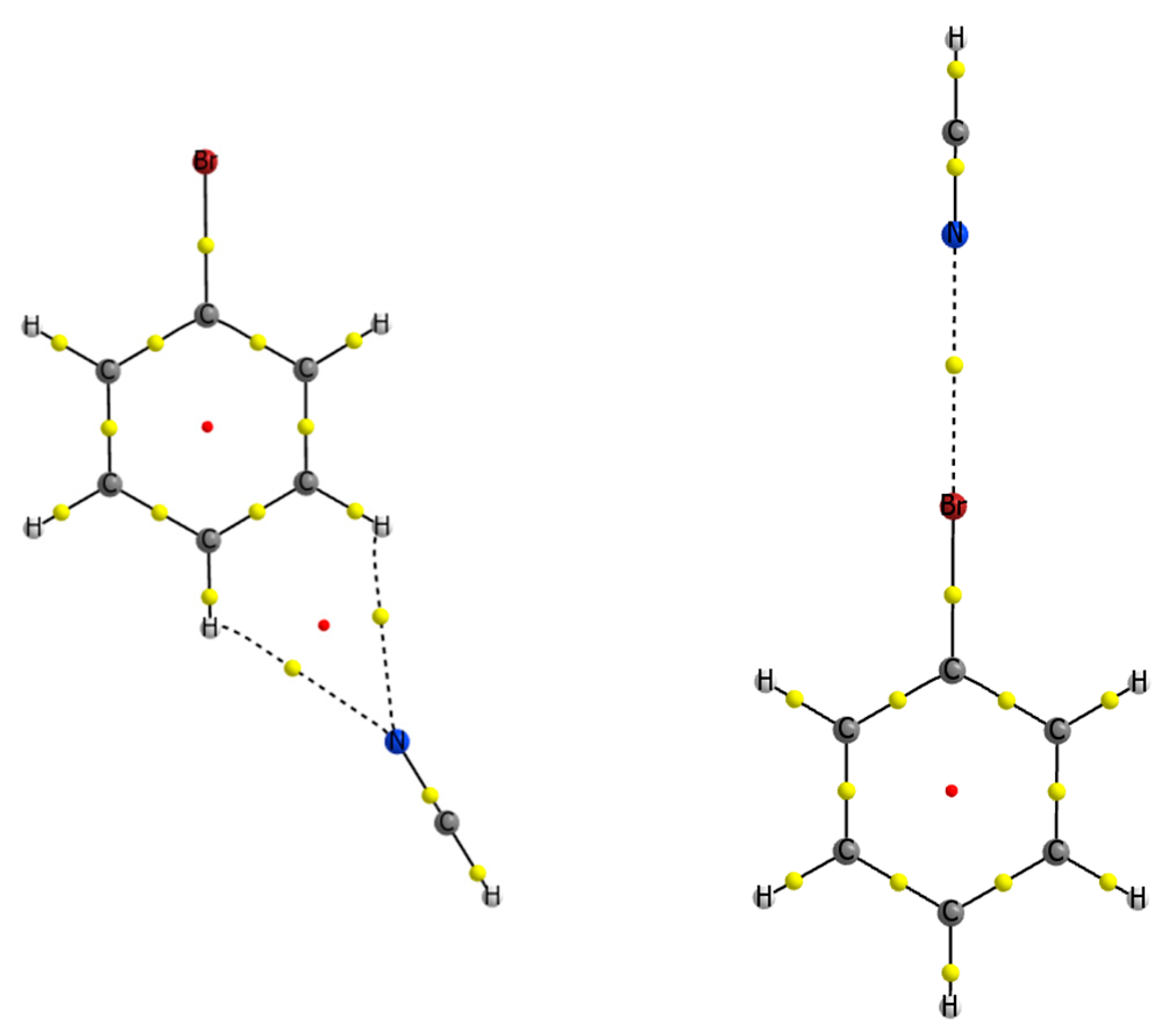

3.3. Hydrogen and Halogen Bonds in 1-Halobenzene

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Frontera, A. Not Only Hydrogen Bonds: Other Noncovalent Interactions. Crystals 2020, 10, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliken, R.S.; Person, W.B. Molecular Complexes: A Lecture and Reprint Volume; Wiley-Interscience: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Legon, A.C. Prereactive Complexes of Dihalogens XY with Lewis Bases B in the Gas Phase: A Systematic Case for the Halogen Analogue B⋅⋅⋅XY of the Hydrogen Bond B⋅⋅⋅HX. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999, 38, 2686–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Y.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Z.; Li, H.; Liu, H.; Zhu, W. Halogen bonding for rational drug design and new drug discovery. Expert Opin. Drug Dis. 2012, 7, 375–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilcken, R.; Zimmermann, M.O.; Lange, A.; Joerger, A.C.; Boeckler, F.M. Principles and Applications of Halogen Bonding in Medicinal Chemistry and Chemical Biology. J. Med. Chem. 2013, 56, 1363–1388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendez, L.; Henriquez, G.; Sirimulla, S.; Narayan, M. Looking Back, Looking Forward at Halogen Bonding in Drug Discovery. Molecules 2017, 22, 1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priimagi, A.; Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. The Halogen Bond in the Design of Functional Supramolecular Materials: Recent Advances. Acc. Chem. Res. 2013, 46, 2686–2695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, G.; Soubhye, J.; Meyer, F. Halogen bonding in polymer science: From crystal engineering to functional supramolecular polymers and materials. Polym. Chem. 2015, 6, 3559–3580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Bisoyi, H.K.; Urbas, A.M.; Bunning, T.J.; Li, Q. The Halogen Bond: An Emerging Supramolecular Tool in the Design of Functional Mesomorphic Materials. Chem. Eur. J. 2019, 25, 1369–1378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metrangolo, P.; Resnati, G. Halogen Bonding. Fundamentals and Applications; Springer: Heidelberg, Germany, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Cavallo, G.; Metrangolo, P.; Milani, R.; Pilati, T.; Priimagi, A.; Resnati, G.; Terraneo, G. The Halogen Bond. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2478–2601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Wong, M.W. Application of Halogen Bonding to Organocatalysis: A Theoretical Perspective. Molecules 2020, 25, 1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S. Halogen Bonding: An Interim Discussion. ChemPhysChem 2013, 14, 278–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, T.; Hennemann, M.; Murray, J.S.; Politzer, P. Halogen bonding: The σ-hole. J. Mol. Model. 2007, 13, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T. Halogen bonding: An electrostatically-driven highly directional noncovalent interaction. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2010, 12, 7748–7757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T. Halogen bonding and other σ-hole interactions: A perspective. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2013, 15, 11178–11189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrafili, M.D.; Mohammadirad, N. Insights into the strength and nature of carbene⋯halogen bond interactions: A theoretical perspective. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 2559–2566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Zhuo, H.Y.; Li, Q.Z.; Yang, X.; Li, W.Z.; Cheng, J.B. Halogen bonds with N-heterocyclic carbenes as halogen acceptors: A partially covalent character. Mol. Phys. 2014, 112, 3024–3032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bene, J.E.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. B4H4 and B4(CH3)4 as Unique Electron Donors in Hydrogen-Bonded and Halogen-Bonded Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 5745–5751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhuo, H.; Yu, H.; Li, Q.; Li, W.; Cheng, J. Some measures for mediating the strengths of halogen bonds with the B–B bond in diborane(4) as an unconventional halogen acceptor. Int. J. Quantum Chem 2014, 114, 128–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, W.; Wang, Y.; Yang, X.; Cheng, J.; Li, Q. Dual function of the boron center of BH(CO)2/BH(N2)2 in halogen- and triel-bonded complexes with hypervalent halogens. J. Mol. Graph. Model. 2018, 84, 118–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; DelBene, J.E. Boron as an Electron-Pair Donor for B⋅⋅⋅Cl Halogen Bonds. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 3112–3119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holloway, J.H.; Legon, A.C. A pseudo-π analogue of a Mulliken bπ.aσ type complex: The rotational spectrum of cyclopropane–chlorine monofluoride. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1997, 93, 373–378. [Google Scholar]

- Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Del Bene, J.E. Unusual acid–base properties of the P4 molecule in hydrogen-, halogen-, and pnicogen-bonded complexes. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 32593–32601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemink, H.I.; Cooke, S.A.; Hinds, K.; Legon, A.C.; Thorn, J.C. The bπ.aσ complex C2H2⋯Cl2 characterised by rotational spectroscopy as an intermediate in a reactive mixture of ethyne and chlorine. J. Chem. Soc. Faraday Trans. 1995, 91, 1891–1900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, A.; Cruz, E.M.; Sarasola, C.; Ugalde, J.M. Density Functional Studies of the bπ.aσ Charge-Transfer Complex Formed between Ethyne and Chlorine Monofluoride. J. Phys. Chem. A 1997, 101, 3021–3024. [Google Scholar]

- Alkorta, I.; Blanco, F.; Deyà, P.M.; Elguero, J.; Estarellas, C.; Frontera, A.; Quiñonero, D. Cooperativity in multiple unusual weak bonds. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2010, 126, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahadevi, A.S.; Sastry, G.N. Cooperativity in Noncovalent Interactions. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 2775–2825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esrafili, M.D.; Mousavian, P.; Mohammadian-Sabet, F. The influence of halogen-bonding cooperativity on the hydrogen and lithium bonds: An ab initio study. Mol. Phys. 2019, 117, 1903–1911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciancaleoni, G. Cooperativity between hydrogen- and halogen bonds: The case of selenourea. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 8506–8514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montis, R.; Arca, M.; Aragoni, M.C.; Bauzá, A.; Demartin, F.; Frontera, A.; Isaia, F.; Lippolis, V. Hydrogen- and halogen-bond cooperativity in determining the crystal packing of dihalogen charge-transfer adducts: A study case from heterocyclic pentatomic chalcogenone donors. CrystEngComm 2017, 19, 4401–4412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S.J. Cooperativity of hydrogen and halogen bond interactions. In 8th Congress on Electronic Structure: Principles and Applications (ESPA 2012): A Conference Selection from Theoretical Chemistry Accounts; Novoa, J.J., Ruiz López, M.F., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2014; pp. 59–68. [Google Scholar]

- Solimannejad, M.; Malekani, M.; Alkorta, I. Cooperativity between the hydrogen bonding and halogen bonding in F3CX ⋯ NCH(CNH) ⋯ NCH(CNH) complexes (X=Cl, Br). Mol. Phys. 2011, 109, 1641–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Del Bene, J.E. Characterizing Traditional and Chlorine-Shared Halogen Bonds in Complexes of Phosphine Derivatives with ClF and Cl2. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 4222–4231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, R.A.; Hill, J.G.; Legon, A.C. Halogen Bonding with Phosphine: Evidence for Mulliken Inner Complexes and the Importance of Relaxation Energy. J. Phys. Chem. A 2016, 120, 8461–8468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donoso-Tauda, O.; Jaque, P.; Elguero, J.; Alkorta, I. Traditional and Ion-Pair Halogen-Bonded Complexes between Chlorine and Bromine Derivatives and a Nitrogen-Heterocyclic Carbene. J. Phys. Chem. A 2014, 118, 9552–9560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Bene, J.E.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. Do Traditional, Chlorine-shared, and Ion-pair Halogen Bonds Exist? An ab Initio Investigation of FCl: CNX Complexes. J. Phys. Chem. A 2010, 114, 12958–12962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grant Hill, J. The halogen bond in thiirane⋯ClF: An example of a Mulliken inner complex. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 19137–19140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloemink, H.I.; Evans, C.M.; Holloway, J.H.; Legon, A.C. Is the gas-phase complex of ammonia and chlorine monofluoride H3N…ClF or [H3NCl]+…F−? Evidence from rotational spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1996, 248, 260–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulliken, R.S. Structures of Complexes Formed by Halogen Molecules with Aromatic and with Oxygenated Solvents1. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1950, 72, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Danovich, D.; Mo, Y.; Shaik, S. On The Nature of the Halogen Bond. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2014, 10, 3726–3737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Danovich, D.; Shaik, S.; Mo, Y. Halogen Bonds in Novel Polyhalogen Monoanions. Chem. Eur. J. 2017, 23, 8719–8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thirman, J.; Engelage, E.; Huber, S.M.; Head-Gordon, M. Characterizing the interplay of Pauli repulsion, electrostatics, dispersion and charge transfer in halogen bonding with energy decomposition analysis. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 905–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, S.M.; Jimenez-Izal, E.; Ugalde, J.M.; Infante, I. Unexpected trends in halogen-bond based noncovalent adducts. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 7708–7710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, K.E.; Hobza, P. Investigations into the Nature of Halogen Bonding Including Symmetry Adapted Perturbation Theory Analyses. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2008, 4, 232–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riley, K.E.; Murray, J.S.; Politzer, P.; Concha, M.C.; Hobza, P. Br⋯O Complexes as Probes of Factors Affecting Halogen Bonding: Interactions of Bromobenzenes and Bromopyrimidines with Acetone. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2009, 5, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riley, K.E.; Murray, J.S.; Fanfrlík, J.; Řezáč, J.; Solá, R.J.; Concha, M.C.; Ramos, F.M.; Politzer, P. Halogen bond tunability II: The varying roles of electrostatic and dispersion contributions to attraction in halogen bonds. J. Mol. Model. 2013, 19, 4651–4659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oliveira, V.; Kraka, E.; Cremer, D. The intrinsic strength of the halogen bond: Electrostatic and covalent contributions described by coupled cluster theory. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2016, 18, 33031–33046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grimes, R.N. Carboranes, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Lepšík, M.; Horinek, D.; Havlas, Z.; Hobza, P. Interaction of Carboranes with Biomolecules: Formation of Dihydrogen Bonds. ChemPhysChem 2006, 7, 1100–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frontera, A.; Bauzá, A. closo-Carboranes as dual CH⋯π and BH⋯π donors: Theoretical study and biological significance. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21, 19944–19950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.; Tu, D.; Poater, J.; Solà, M. nido-Cage⋯π Bond: A Non-covalent Interaction between Boron Clusters and Aromatic Rings and Its Applications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fanfrlík, J.; Holub, J.; Růžičková, Z.; Řezáč, J.; Lane, P.D.; Wann, D.A.; Hnyk, D.; Růžička, A.; Hobza, P. Competition between Halogen, Hydrogen and Dihydrogen Bonding in Brominated Carboranes. ChemPhysChem 2016, 17, 3373–3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de las Nieves Piña, M.; Bauzá, A.; Frontera, A. Halogen⋯halogen interactions in decahalo-closo-carboranes: CSD analysis and theoretical study. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2020, 22, 6122–6130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aullón, G.; Laguna, A.; Filippov, O.A.; Oliva-Enrich, J.M. Trinuclear Gold–Carborane Cluster as a Host Structure. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2019, 2019, 18–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, O.; Gimeno, M.C.; Laguna, A.; Ospino, I.; Aullón, G.; Oliva, J.M. Organometallic gold complexes of carborane. Theoretical comparative analysis of ortho, meta, and para derivatives and luminescence studies. Dalton Trans. 2009, 3807–3813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grabowski, S.J.; Casanova, D.; Formoso, E.; Ugalde, J.M. Tetravalent Oxygen and Sulphur Centres Mediated by Carborane Superacid: Theoretical Analysis. ChemPhysChem 2019, 20, 2443–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Møller, C.; Plesset, M.S. Note on an Approximation Treatment for Many-Electron Systems. Phys. Rev. 1934, 46, 618–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunning, T.H. Gaussian-Basis Sets for Use in Correlated Molecular Calculations 1. The Atoms Boron through Neon and Hydrogen. J. Chem. Phys. 1989, 90, 1007–1023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, K.A.; Puzzarini, C. Systematically convergent basis sets for transition metals. II. Pseudopotential-based correlation consistent basis sets for the group 11 (Cu, Ag, Au) and 12 (Zn, Cd, Hg) elements. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2005, 114, 283–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, A.; Helgaker, T.; Jørgensen, P.; Klopper, W.; Olsen, J. Basis-set convergence of the energy in molecular Hartree–Fock calculations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1999, 302, 437–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halkier, A.; Klopper, W.; Helgaker, T.; Jørgensen, P.; Taylor, P.R. Basis set convergence of the interaction energy of hydrogen-bonded complexes. J. Chem. Phys. 1999, 111, 9157–9167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frisch, M.J.; Trucks, G.W.; Schlegel, H.B.; Scuseria, G.E.; Robb, M.A.; Cheeseman, J.R.; Scalmani, G.; Barone, V.; Petersson, G.A.; Nakatsuji, H.; et al. Gaussian 16 Rev. A.03; Gaussian Inc.: Wallingford, CT, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Werner, H.J.; Knowles, P.J.; Knizia, G.; Manby, F.R.; Schütz, M.; Celani, P.; Györffy, W.; Kats, D.; Korona, T.; Lindh, R.; et al. MOLPRO, Version 2012.1, A Package of ab Initio Programs, 2012.

- Murray, J.S.; Lane, P.; Politzer, P. Expansion of the σ-hole concept. J. Mol. Model. 2009, 15, 723–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Politzer, P.; Murray, J.S.; Clark, T.; Resnati, G. The σ-hole revisited. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 32166–32178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, T.; Chen, F. Multiwfn: A multifunctional wavefunction analyzer. J. Comput. Chem. 2012, 33, 580–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jmol: An Open-Source Java Viewer for Chemical Structures in 3D. Available online: http://www.jmol.org/ (accessed on 24 February 2020).

- Bader, R.F.W. Atoms in Molecules: A Quantum Theory; Clarendon Press: Oxford, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Popelier, P.L.A. Atoms in Molecules. An introduction; Prentice Hall: Harlow, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cremer, D.; Kraka, E. A description of the chemical bond in terms of local properties of electron density and energy. Croat. Chem. Acta 1984, 57, 1259–1281. [Google Scholar]

- Rozas, I.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. Behavior of Ylides Containing N, O, and C Atoms as Hydrogen Bond Acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11154–11161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keith, T.A. AIMAll; Version 17.11.14 B; TK Gristmill Software: Overland Park, KS, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Mori-Sánchez, P.; Contreras-García, J.; Cohen, A.J.; Yang, W. Revealing Noncovalent Interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 6498–6506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Contreras-García, J.; Johnson, E.R.; Keinan, S.; Chaudret, R.; Piquemal, J.P.; Beratan, D.N.; Yang, W. NCIPLOT: A Program for Plotting Noncovalent Interaction Regions. J. Chem. Theor. Comput. 2011, 7, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphrey, W.; Dalke, A.; Schulten, K. VMD: Visual molecular dynamics. J. Mol. Graph. 1996, 14, 33–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D. Natural Energy Decomposition Analysis: Extension to Density Functional Methods and Analysis of Cooperative Effects in Water Clusters. J. Phys. Chem. A 2005, 109, 11936–11940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D. Natural Energy Decomposition Analysis: Explicit Evaluation of Electrostatic and Polarization Effects with Application to Aqueous Clusters of Alkali Metal Cations and Neutrals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1996, 118, 2473–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reed, A.E.; Curtiss, L.A.; Weinhold, F. Intermolecular Interactions from a Natural Bond Orbital, Donor-Acceptor Viewpoint. Chem. Rev. 1988, 88, 899–926. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glendening, E.D.; Reed, A.E.; Carpenter, J.E.; Bohmann, J.A.; Morales, C.M.; Karafiloglou, P.; Landis, C.R.; Weinhold, F. NBO 7.0; Theoretical Chemistry Institute, University of Wisconsin: Madison, WI, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Allen, F. The Cambridge Structural Database: A quarter of a million crystal structures and rising. Acta Cryst. B 2002, 58, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozas, I.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. Bifurcated Hydrogen Bonds: Three-Centered Interactions. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 9925–9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chęcińska, L.; Grabowski, S.J.; Małecka, M. An analysis of bifurcated H-bonds: Crystal and molecular structures of O, O-diphenyl 1-(3-phenylthioureido) pentanephosphonate and O,O-diphenyl 1-(3-phenylthioureido)butanephosphonate. J. Phys. Org. Chem. 2003, 16, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, I.; Alkorta, I.; Molins, E.; Espinosa, E. Universal Features of the Electron Density Distribution in Hydrogen-Bonding Regions: A Comprehensive Study Involving H⋯X (X = H, C, N, O, F, S, Cl, pi) Interactions. Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 2442–2452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alkorta, I.; Solimannejad, M.; Provasi, P.; Elguero, J. Theoretical Study of Complexes and Fluoride Cation Transfer between N2F+ and Electron Donors. J. Phys. Chem. A 2007, 111, 7154–7161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Sanz, G.; Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J. Theoretical study of the HXYH dimers (X, Y = O, S, Se). Hydrogen bonding and chalcogen–chalcogen interactions. Mol. Phys. 2011, 109, 2543–2552. [Google Scholar]

| o-B10H11C2X | m-B10H11C2X | p-B10H11C2X | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H | X | H | X | H | X | |

| X = H | 0.068 | 0.068 | 0.052 | 0.052 | 0.048 | 0.048 |

| F | 0.069 | – * | 0.059 | −0.018 | 0.054 | −0.022 |

| Cl | 0.067 | 0.034 | 0.058 | 0.021 | 0.054 | 0.017 |

| Br | 0.067 | 0.043 | 0.058 | 0.031 | 0.054 | 0.027 |

| I | 0.065 | 0.059 | 0.057 | 0.047 | 0.053 | 0.043 |

| o-B10H11C2X | m-B10H11C2X | p-B10H11C2X | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HB | XB | HB | XB | HB | XB | |

| X = H | 24.8 | 17.3 | 16.0 | |||

| F | 22.0 | 18.8 | 17.3 | |||

| Cl | 22.1 | 11.9 | 18.8 | 9.2 | 17.3 | 8.0 |

| Br | 22.0 | 15.9 | 18.6 | 12.8 | 17.3 | 11.8 |

| I | 22.0 | 21.8 | 18.4 | 18.4 | 17.0 | 17.1 |

| o-B10H11C2X | m-B10H11C2X | p-B10H11C2X | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| H⋯N (HB) | X⋯N (XB) | H⋯N (HB) | X⋯N (XB) | H⋯N (HB) | X⋯N (XB) | |

| X = H | 2.491 | 2.239 | 2.255 | |||

| F | 2.168 | 2.221 | 2.242 | |||

| Cl | 2.162 | 3.006 | 2.220 | 2.982 | 2.241 | 3.020 |

| Br | 2.159 | 3.037 | 2.220 | 3.012 | 2.240 | 3.059 |

| I | 2.159 | 3.050 | 2.222 | 3.022 | 2.240 | 3.071 |

| HB | XB | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De | N⋯H | De | N⋯X | |

| X = H | 8.1 | 2.720 | ||

| F | 9.5 | 2.694 | ||

| Cl | 10.0 | 2.689 | 3.9 | 3.183 |

| Br | 10.2 | 2.675 | 6.4 | 3.148 |

| I | 10.3 | 2.682 | 10.7 | 3.223 |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Alkorta, I.; Elguero, J.; Oliva-Enrich, J.M. Hydrogen vs. Halogen Bonds in 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes. Materials 2020, 13, 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13092163

Alkorta I, Elguero J, Oliva-Enrich JM. Hydrogen vs. Halogen Bonds in 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes. Materials. 2020; 13(9):2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13092163

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlkorta, Ibon, Jose Elguero, and Josep M. Oliva-Enrich. 2020. "Hydrogen vs. Halogen Bonds in 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes" Materials 13, no. 9: 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13092163

APA StyleAlkorta, I., Elguero, J., & Oliva-Enrich, J. M. (2020). Hydrogen vs. Halogen Bonds in 1-Halo-Closo-Carboranes. Materials, 13(9), 2163. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13092163