Comparison of Carbon Supports in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells

Abstract

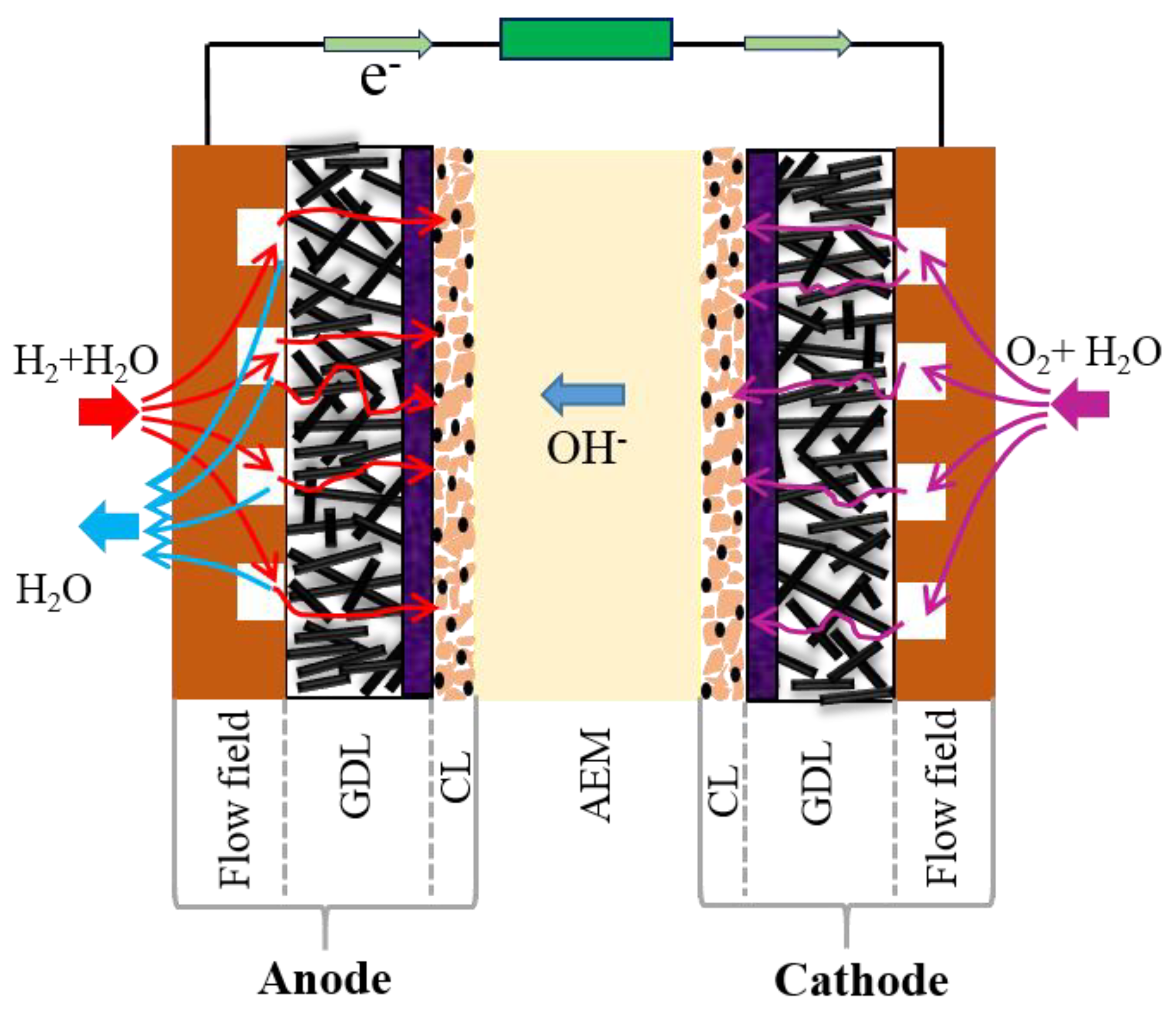

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Materials and Methods

2.1. Ag/C Catalyst Synthesis

2.2. Catalyst Characterization

2.3. Fuel Cell Assembly and Testing

3. Results and Discussion

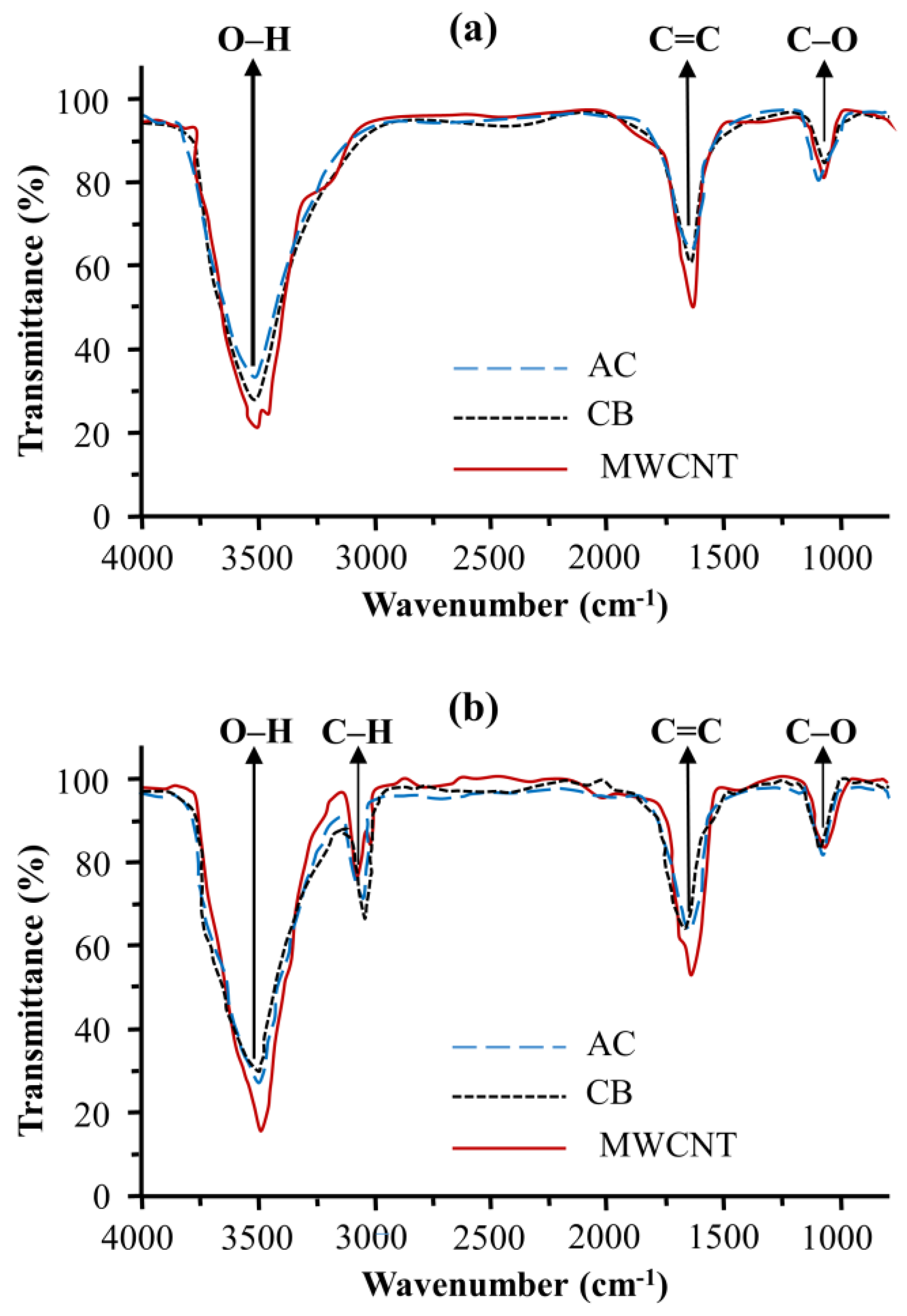

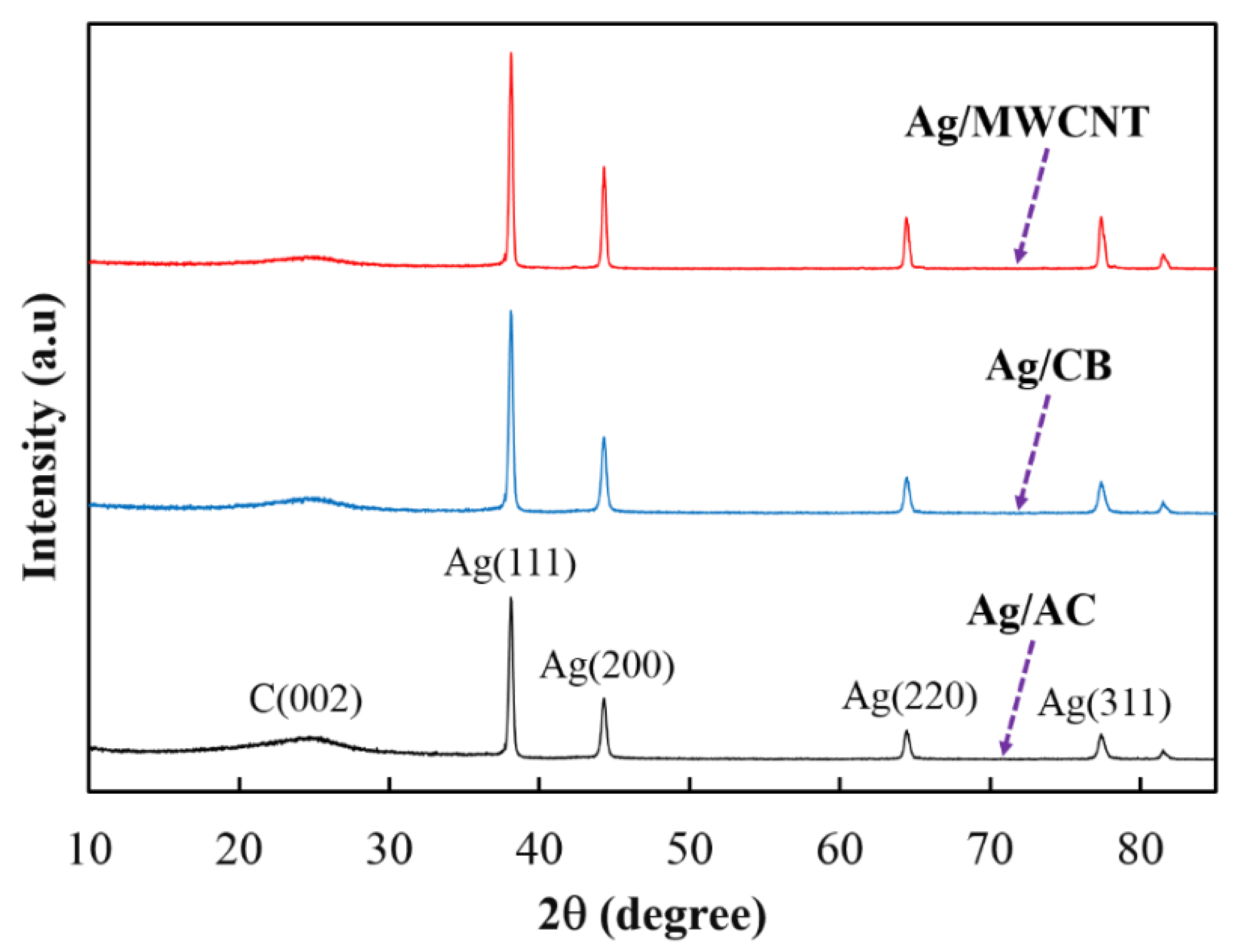

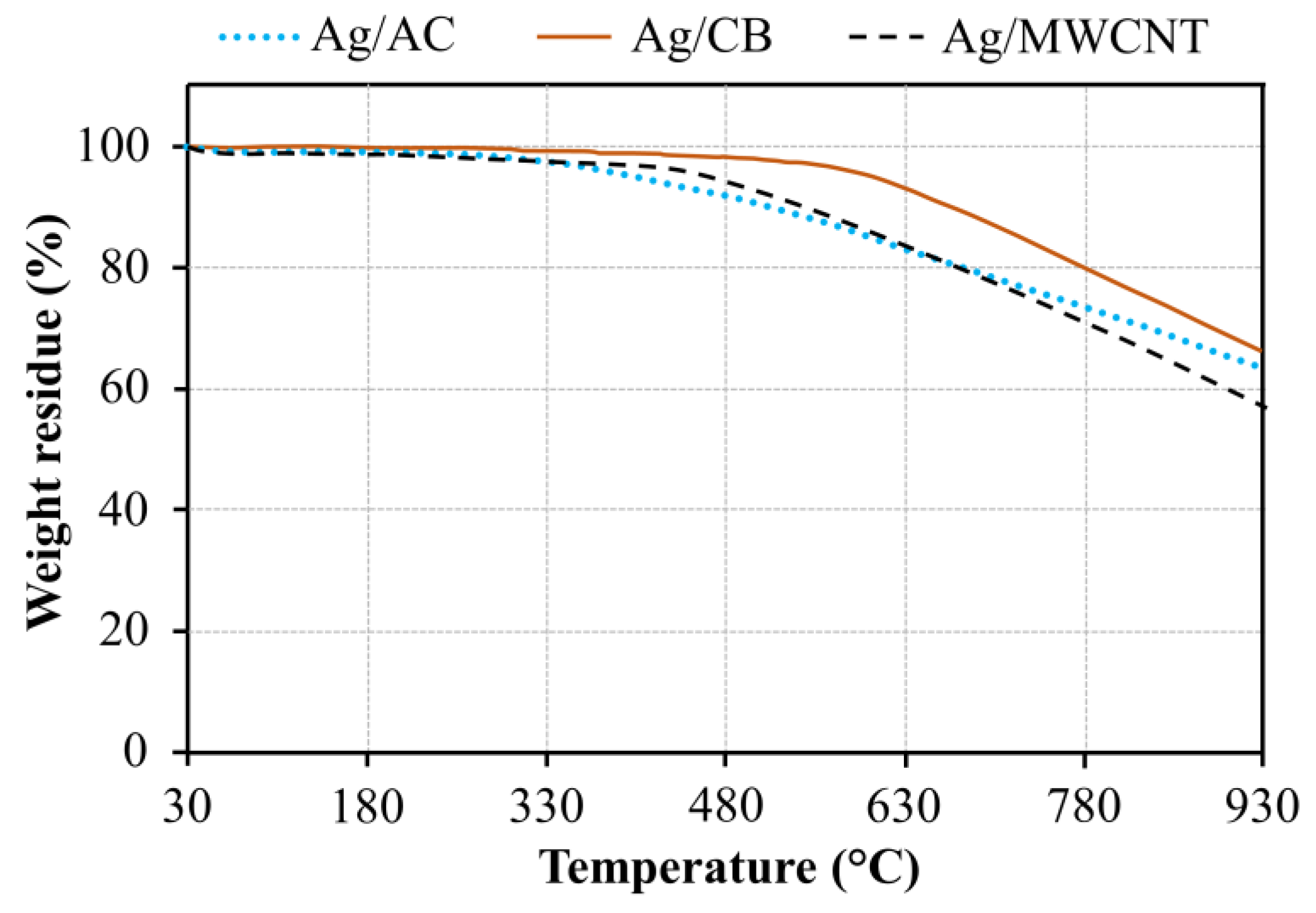

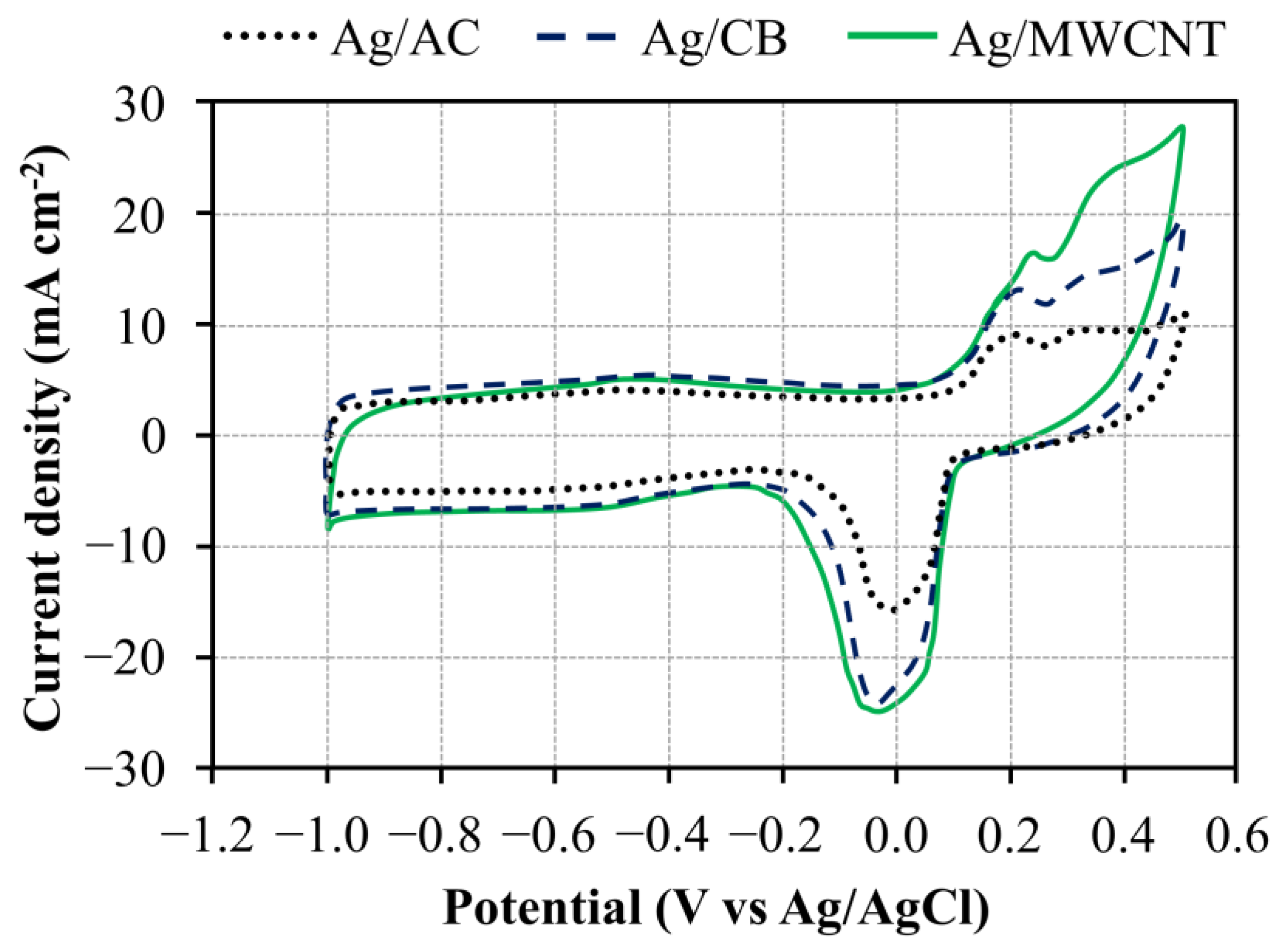

3.1. Catalyst Characterization

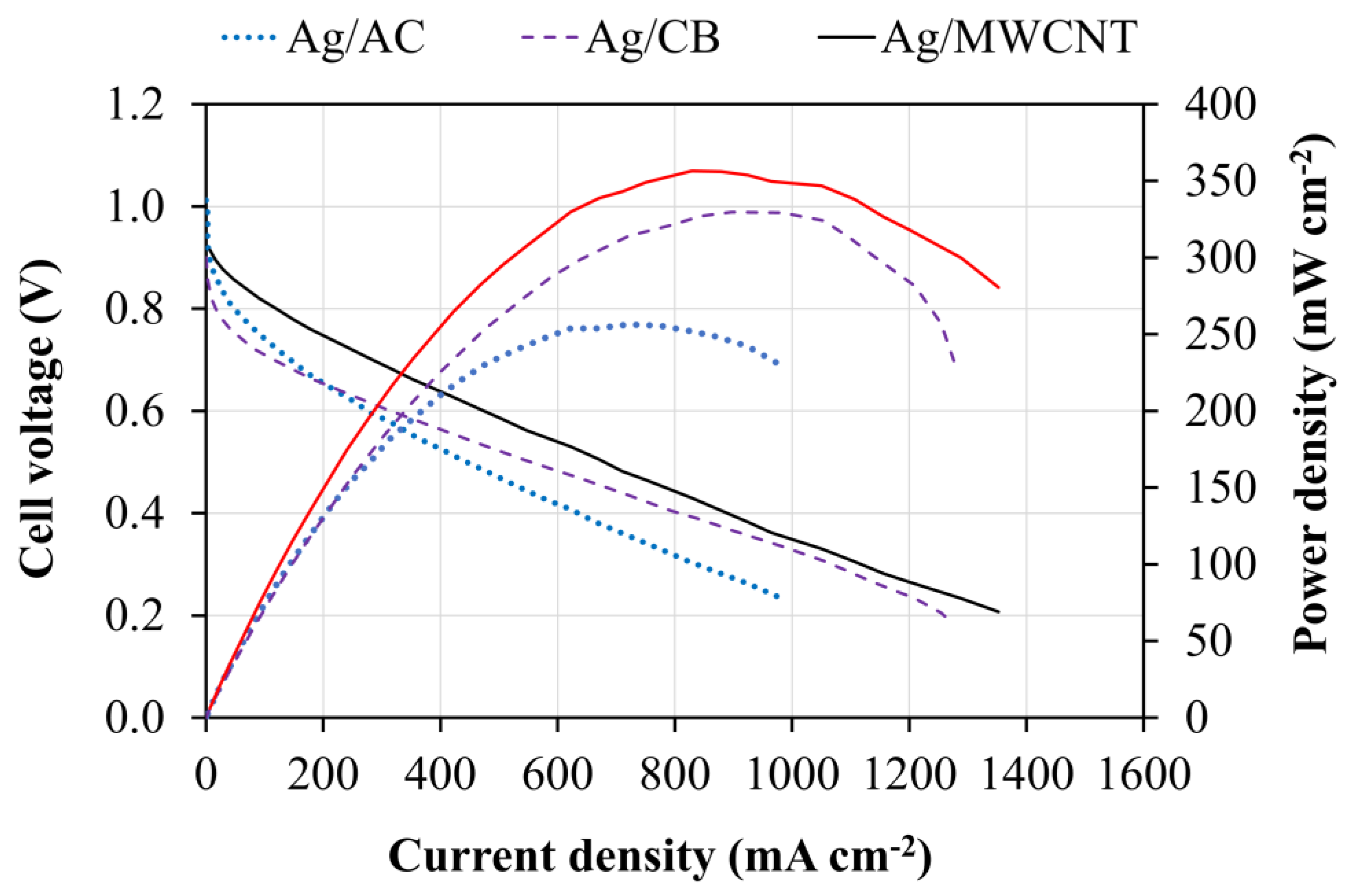

3.2. Fuel Cell Performance

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ramli, Z.A.C.; Kamarudin, S.K. Platinum-Based Catalysts on Various Carbon Supports and Conducting Polymers for Direct Methanol Fuel Cell Applications: A Review. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 2018, 13, 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J. Barriers of scaling-up fuel cells: Cost, durability and reliability. Energy 2015, 80, 509–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varcoe, J.R.; Atanassov, P.; Dekel, D.R.; Herring, A.M.; Hickner, M.A.; Kohl, P.A.; Kucernak, A.R.; Mustain, W.E.; Nijmeijer, K.; Scott, K.; et al. Anion-exchange membranes in electrochemical energy systems. Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 3135–3191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, X.; Sumboja, A.; Wuu, D.; An, T.; Li, B.; Goh, F.W.T.; Hor, T.S.A.; Zong, Y.; Liu, Z. Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Media: From Mechanisms to Recent Advances of Catalysts. ACS Catal. 2015, 5, 4643–4667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fellinger, T.-P.; Antonietti, M. Efficient Metal-Free Oxygen Reduction in Alkaline Medium on High-Surface-Area Mesoporous Nitrogen-Doped Carbons Made from Ionic Liquids and Nucleobases. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 206–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šljukić, B.; Banks, C.E.; Compton, R.G. An overview of the electrochemical reduction of oxygen at carbon-based modified electrodes. J. Iran. Chem. Soc. 2005, 2, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trogadas, P.; Fuller, T.F.; Strasser, P. Carbon as catalyst and support for electrochemical energy conversion. Carbon 2014, 75, 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messias, S.; Nunes da Ponte, M.; Reis-Machado, A.S. Carbon Materials as Cathode Constituents for Electrochemical CO2 Reduction—A Review. J. Carbon Res. 2019, 5, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canda, L.; Heput, T.; Ardelean, E. Methods for recovering precious metals from industrial waste. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, International Conference on Applied Sciences, Wuhan, China, 3–5 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, S.; Sun, G.; Qi, J.; Sun, S.; Guo, J.; Xin, Q.; Haarberg, G.M. Review of New Carbon Materials as Catalyst Supports in Direct Alcohol Fuel Cells. Chin. J. Catal. 2010, 31, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostazo-López, M.J.; Salinas-Torres, D.; Ruiz-Rosas, R.; Morallón, E.; Cazorla-Amorós, D. Nitrogen-Doped Superporous Activated Carbons as Electrocatalysts for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Materials 2019, 12, 1346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flores-Lasluisa, J.X.; Quílez-Bermejo, J.; Ramírez-Pérez, A.C.; Huerta, F.; Cazorla-Amorós, D.; Morallón, E. Copper-Doped Cobalt Spinel Electrocatalysts Supported on Activated Carbon for Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. Materials 2019, 12, 1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasa, B.; Martino, E.; Vakros, J.; Trakakis, G.; Galiotis, C.; Katsaounis, A. Effect of Carbon Support on the Electrocatalytic Properties of Pt−Ru Catalysts. ChemElectroChem 2019, 6, 4970–4979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anuar, S.A.; Loh, K.S.; Samad, S.; Abidin, A.F.Z.; Wong, W.Y.; Mohamad, A.B.; Lee, T.K. Effect of Carbon Supports on Oxygen Reduction Reaction of Iron/Cobalt Electrocatalyst. Int. J. Nanoelectron. Mater. 2020, 13, 225–232. [Google Scholar]

- Molina-García, M.A.; Rees, N.V. Effect of catalyst carbon supports on the oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline media: A comparative study. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 94669–94681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barsuk, D.; Zadick, A.; Chatenet, M.; Georgarakis, K.; Panagiotopoulos, N.T.; Champion, Y.; Moreira Jorge, A. Nanoporous silver for electrocatalysis application in alkaline fuel cells. Mater. Des. 2016, 111, 528–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidault, F.; Kucernak, A. A novel cathode for alkaline fuel cells based on a porous silver membrane. J. Power Sources 2010, 195, 2549–2556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, H.; Shen, P.K. Novel Pt-free catalyst for oxygen electroreduction. Electrochem. Commun. 2006, 8, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, L.; Zhang, Z.; Wang, Z.; Qi, J.; Li, W. Carbon supported Ag nanoparticles as high performance cathode catalyst for H2/O2 anion exchange membrane fuel cell. Front. Chem. 2013, 1, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia, A.C.; Gasparotto, L.H.S.; Gomes, J.F.; Tremiliosi-Filho, G. Straightforward Synthesis of Carbon-Supported Ag Nanoparticles and Their Application for the Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Electrocatalysis 2012, 3, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatenet, M.; Genies-Bultel, L.; Aurousseau, M.; Durand, R.; Andolfatto, F. Oxygen reduction on silver catalysts in solutions containing various concentrations of sodium hydroxide—Comparison with platinum. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2002, 32, 1131–1140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.; Lu, X.; Li, Z.; Zhang, H.; Cui, X.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, F.; Deng, Y. Silver-molybdate electrocatalysts for oxygen reduction reaction in alkaline media. Electrochem. Commun. 2012, 20, 171–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, V.M.; Yang, M.-K.; Yang, H. Functionalized Carbon Black Supported Silver (Ag/C) Catalysts in Cathode Electrode for Alkaline Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Int. J. Precis. Eng. Manuf. Green Technol. 2019, 6, 711–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmo, M.; Linardi, M.; Poco, J.G.R. Characterization of nitric acid functionalized carbon black and its evaluation as electrocatalyst support for direct methanol fuel cell applications. Appl. Catal. A Gen. 2009, 355, 132–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balachandran, M. Synthesis and Characterization of Carbon nanospheres from hydrocarbon soot. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 2012, 7, 9537–9549. [Google Scholar]

- Pulidindi, I. Notes Surface functionalities of nitric acid treated carbon—A density functional theory based vibrational analysis. Indian J. Chem. Sect. A 2009, 48 A, 352–356. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, D.S.; Haider, A.J.; Mohammad, M.R. Comparesion of Functionalization of Multi-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Treated by Oil Olive and Nitric Acid and their Characterization. Energy Procedia 2013, 36, 1111–1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Yin, G.; Shao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y. Effect of carbon black support corrosion on the durability of Pt/C catalyst. J. Power Sources 2007, 171, 331–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, P.; Kim, Y.J.; Singh, H.; Wang, C.; Hwang, K.H.; Farh, M.E.-A.; Yang, D.C. Biosynthesis, characterization, and antimicrobial applications of silver nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 2015, 10, 2567–2577. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Jia, X.; Tang, A.; Zhu, X.; Meng, H.; Wang, Y. Preparation of Spherical and Triangular Silver Nanoparticles by a Convenient Method. Integr. Ferroelectr. 2012, 136, 9–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Zhong, C.-J.; Liu, C.-J. Highly Active and Stable Pt-Pd Alloy Catalysts Synthesized by Room-Temperature Electron Reduction for Oxygen Reduction Reaction. Adv. Sci. 2017, 4, 1600486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alimohammadi, F.; Gashti, M.P.; Shamei, A.; Kiumarsi, A. Deposition of silver nanoparticles on carbon nanotube by chemical reduction method: Evaluation of surface, thermal and optical properties. Superlattices Microstruct. 2012, 52, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maheswari, S.; Sridhar, P.; Pitchumani, S. Carbon-Supported Silver as Cathode Electrocatalyst for Alkaline Polymer Electrolyte Membrane Fuel Cells. Electrocatalysis 2012, 3, 13–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Hsu, A.; Chu, D.; Chen, R. Improving Oxygen Reduction Reaction Activities on Carbon-Supported Ag Nanoparticles in Alkaline Solutions. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 4324–4330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohmann-Richters, F.P.; Abel, B.; Varga, Á. In situ determination of the electrochemically active platinum surface area: Key to improvement of solid acid fuel cells. J. Mater. Chem. A 2018, 6, 2700–2707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Choi, S.; Kim, Y.; Yoon, J.; Im, S.; Choo, H. Improvement of Fuel Cell Durability Performance by Avoiding High Voltage. Int. J. Automot. Technol. 2019, 20, 1113–1121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corradini, P.; Pires, F.; Paganin, V.; Perez, J.; Antolini, E. Effect of the relationship between particle size, inter-Particle distance, and metal loading of carbon supported fuel cell catalysts on their catalytic activity. J. Nanopart. Res. 2012, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holade, Y.; Morais, C.; Servat, K.; Napporn, T.W.; Kokoh, K.B. Enhancing the available specific surface area of carbon supports to boost the electroactivity of nanostructured Pt catalysts. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2014, 16, 25609–25620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hu, M.; Xu, W.; Wu, X.; Jiang, J. Catalytically Active Carbon From Cattail Fibers for Electrochemical Reduction Reaction. Front. Chem. 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-Y.; Hou, Y.-N.; Zhang, X.; Yang, Z.-N.; Xu, T.; Wang, A.-J. Activating electrochemical catalytic activity of bio-palladium by hybridizing with carbon nanotube as “e− Bridge”. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Begum, H.; Ahmed, M.S.; Lee, D.-W.; Kim, Y.-B. Carbon nanotubes-based PdM bimetallic catalysts through N4-system for efficient ethanol oxidation and hydrogen evolution reaction. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 11051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamzah, N.; Yasin, M.F.M.; Yusop, M.Z.M.; Saat, A.; Subha, N.A.M. Rapid production of carbon nanotubes: A review on advancement in growth control and morphology manipulations of flame synthesis. J. Mater. Chem. A 2017, 5, 25144–25170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, V.; Rajaura, R.; Purohit, S.D.; Patidar, D.; Sharma, K. Cost Effective Synthesis of Carbon Nanotubes and Evaluation of their Antibacterial Activity. Nano Trends A J. Nanotechnol. Appl. 2013, 14, 8–12. [Google Scholar]

- Algadri, N.A.; Ibrahim, K.; Hassan, Z.; Bououdina, M. Cost-effective single-step carbon nanotube synthesis using microwave oven. Mater. Res. Express 2017, 4, 085602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Truong, V.M.; Duong, N.B.; Yang, H. Comparison of Carbon Supports in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Materials 2020, 13, 5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235370

Truong VM, Duong NB, Yang H. Comparison of Carbon Supports in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Materials. 2020; 13(23):5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235370

Chicago/Turabian StyleTruong, Van Men, Ngoc Bich Duong, and Hsiharng Yang. 2020. "Comparison of Carbon Supports in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells" Materials 13, no. 23: 5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235370

APA StyleTruong, V. M., Duong, N. B., & Yang, H. (2020). Comparison of Carbon Supports in Anion Exchange Membrane Fuel Cells. Materials, 13(23), 5370. https://doi.org/10.3390/ma13235370