Abstract

With the continuous development of oil and gas fields, the demand for corrosion-resistant tubing is increasing, which is important for the safe exploitation of oil and gas energy. Due to its excellent CO2 corrosion resistance, 13Cr-110 martensitic stainless steel is widely used in sour gas-containing oil fields in western China. This paper describes a case of stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in a 13Cr-110 serviced in an ultra-deep gas well. The failure mode of the tubing is brittle along the lattice fracture, and the cracks are generated because of nitrogen gas-lift production-enhancement activities during the service of the tubing, leading to corrosion damage zones and cracks in the 13Cr-110 material under the synergistic effect of oxygen and chloric acid-containing environments. During subsequent production, the tubing is subjected to tensile stresses and cracks expanded at the 13Cr-110 lattice boundaries due to reduced structural strength in the corrosion region. To address the corrosion sensitivity of 13Cr-110 in an oxygen environment, it is recommended that the oxygen content in the wellbore be strictly controlled and that antioxidant corrosion inhibitors be added.

1. Introduction

Energy security is a critical guarantee for national economic and social stability. With the continuous growth in global energy demand and advancements in energy extraction technologies, the oil and gas industries face increasingly severe challenges. As a high-strength and corrosion-resistant material, 13Cr tubing offers significant advantages in improving energy extraction efficiency, reducing maintenance costs, and enhancing environmental adaptability, all of which are crucial for ensuring national energy security [1,2,3,4]. In recent years, market research data have shown that the demand for 13Cr tubing is increasing annually, and it is expected to continue growing in the coming years. The main driving factors include the growth in global energy demand, the increasing difficulty of oil and gas extraction, and the higher demand for high-quality tubing materials [5,6,7,8,9].

The application of 13Cr tubing in high-acid environments is challenged by the risk of stress corrosion cracking (SCC). SCC is a brittle fracture phenomenon that occurs under the combined effects of specific corrosive media and stress, and it poses a significant threat to the safe operation of tubing due to its hidden and sudden nature [10,11,12,13]. In high-acid environments, SCC is influenced by multiple factors, including the composition of the corrosive medium, temperature, pH, and the stress state of the material. Studies have shown that the presence of H2S and CO2 is a key factor in promoting SCC. Acidic media reduce the stability of the protective film on the steel surface, accelerating the corrosion process. Higher temperatures enhance atomic diffusion in metals, thus accelerating crack propagation. Additionally, different pH values affect the protective effectiveness of the metal’s passive film, influencing the sensitivity to SCC. Furthermore, researchers have found that 13Cr materials exhibit stress corrosion cracking in oxygen-containing environments [14,15]. Oxygen, as a strong oxidizer, significantly accelerates the corrosion process, especially at high temperatures where its activity increases, promoting crack initiation and propagation. Under constant stress conditions, the crack propagation rate of SCC shows significant differences at various oxygen concentrations and temperatures. High oxygen concentration and high temperature conditions result in faster crack propagation, indicating a synergistic effect of these two conditions in accelerating the corrosion process. Existing research also indicates that high mechanical stresses, such as residual stress and working stress, increase the risk of SCC in materials.

In this work, we investigated the failure causes of 13Cr-110 tubing in a gas well through magnetic particle inspection, chemical and mechanical properties testing, energy dispersive spectrometer, and X-ray diffraction analysis. We also conducted collapse stress finite element analysis. The aim was to identify the collapse failure causes of the tubing and propose corresponding suggestions to prevent similar failure accidents from happening again, thus supporting the continuous supply of oil and gas energy.

2. Background of 13Cr-110 Tubing Failure

Failure Process

Due to the geological conditions of oil fields in western China, 13Cr-110 is often used in wells with high temperature, high pressure, and high chloride ion content. The 13Cr-110 tubing has been in service for 15 years. The well underwent open nitrogen gas lift and liquid discharge three times in April 2013, October 2017, and August 2019. The method was coiled tubing + nitrogen production vehicle injection nitrogen gas lift. The working conditions of the three gas-lift and liquid discharge operations are shown in Table 1. In April 2022, the well contained a high water content and was shut down. This well has undergone three nitrogen lifts. According to interviews with engineers working on site, the nitrogen content in the nitrogen generator is 99% and the oxygen content is 1%, which means that it is impossible for nitrogen lift operations to reduce the oxygen content to 0. Table 1 shows the information of nitrogen lift operations, which is also a supplement to the source of oxygen, indicating that this well is at risk of oxygen corrosion.

Table 1.

The operation conditions of gas lift and liquid drainage.

In August 2023, during the pipe string replacement operation, it was found that the first 13Cr-110 oil pipe (hereinafter marked as 1# oil pipe) was broken since the oil pipe was hung. It was 16.2 m deep and 8.36 m long above the break point. The length of the sample oil pipe is 0.5 m, and the pipe string below the cross section falls into the well.

Analysis of the crude oil from this well showed that it contained a small amount of sulfur (Table 2). Natural gas contains carbon dioxide and does not contain hydrogen sulfide (Table 3). It should be emphasized that such low concentrations are insufficient to trigger a sweet (CO₂) corrosion mechanism. Nitrogen gas-lift and liquid drainage operations were carried out for 1 day, 32 days, and 3 days in 2013, 2017, and 2019, respectively. From 2016 to 2020, oxygen was detected at the wellhead, the gas gathering station, and the outlet of the medium-pressure metering separator. The chloride ion concentration of the formation water reaches a maximum of 119,200 mg/L, the total salinity reaches a maximum of 199,700 mg/L, and the calcium ion concentration reaches a maximum of 6990 mg/L. The pH of the formation water is weakly acidic and neutral, and it belongs to the calcium chloride water type (Table 4).

Table 2.

Crude oil composition detection data table of the well.

Table 3.

Natural gas composition detection data table of the well.

Table 4.

Formation water composition detection data table of the well.

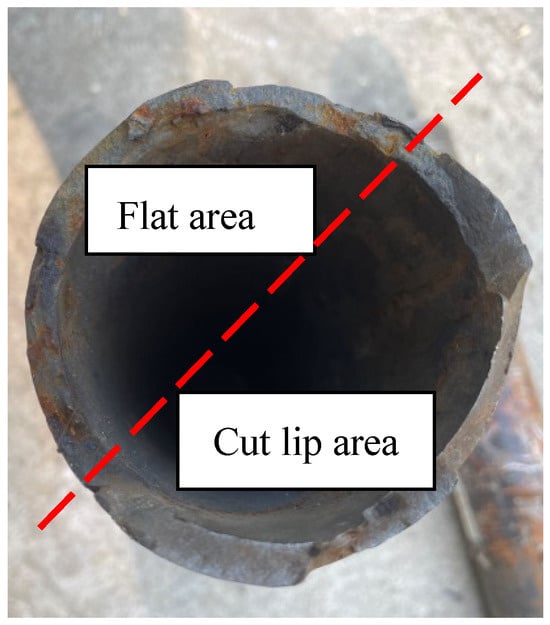

3. Macromorphological Analysis

The macro photos of the broken oil pipes submitted for inspection are shown in Figure 1. The 1# failed oil pipe was broken in the transverse direction, while the 2# oil pipe was not broken and had only mechanical damage to the outer wall. The macroscopic morphological photos of the fracture of the 1# oil pipe are shown in Figure 2 and Figure 3. The fracture location of the oil pipe is 16.2 m deep. There is no obvious deformation of the pipe body near the fracture. Part of the fracture is rusty yellow, and there are flat areas and shear lip areas on the section. The shear lip area accounts for about 1/2 of the circumference, and cracks can be seen along the wall thickness direction on the fracture surface. The cracks do not extend to the outer wall. It is preliminarily inferred that the fracture of the 1# oil pipe is a brittle fracture.

Figure 1.

Photo of broken oil pipe.

Figure 2.

Macroscopic morphology of the fracture surface of 1# oil pipe.

Figure 3.

Partial morphology of the fracture of 1# oil pipe.

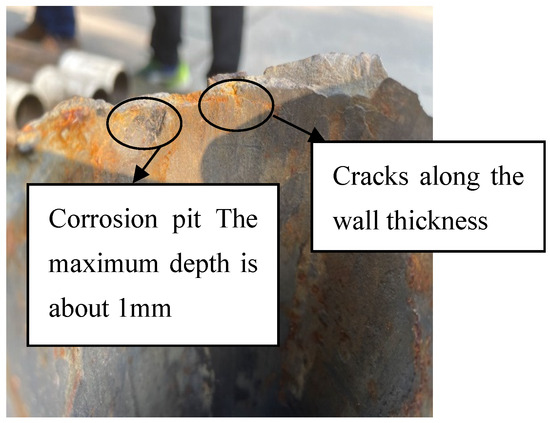

The macroscopic morphology of the inner surface of the broken oil pipe is shown in Figure 4. There is a corrosion pit in the fracture area of the 1# oil pipe, with a maximum depth of about 1 mm. The inner surface of the pipe is smooth and slightly corroded.

Figure 4.

Internal surface morphology of 1# oil pipe.

4. Geometry Measurement

A micrometer was used to measure the outer diameter of the 1# oil pipe body and the 2# oil pipe body, and a thickness gauge was used to measure the wall thickness of the 1# oil pipe body and the 2# oil pipe body. The measurement results are shown in Table 5. The oil pipe was put into service in 2008. This failure analysis and testing were based on an oilfield site-customized ordering agreement. The measurement results showed that for the outer diameter of the 1 and 2# oil pipes, except for the fractured part, the wall thickness complies with the size requirements of technology standard for 88.9 mm × 6.45 mm 13Cr oil pipes. It should be emphasized that the failure was related to a localized one (i.e., not a general corrosion mechanism).

Table 5.

Measurement results of geometric dimensions of 1# and 2# oil pipe bodies.

5. Non-Destructive Testing (NDT)

The two pipe bodies were sectioned, and the internal and external surfaces of the sectioned oil pipes were subjected to magnetic particle flaw detection. It can be seen from the test results that there are no obvious cracks on the inner and outer surfaces of the 1# oil pipe and 2# oil pipe, as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6.

Figure 5.

Magnetic particle inspection photos of the inner and outer surfaces of 1# oil pipe.

Figure 6.

Magnetic particle inspection photos of the inner and outer surfaces of 2# oil pipe.

6. Chemical Composition Analysis

According to the standard [16], chemical composition analysis samples were taken from the 1# oil pipe body and the 2# oil pipe body, respectively. There were two spectra for each pipe body, a total of four samples. The ARL 4460 direct reading spectrometer was used to analyze its chemical composition. The results are shown in Table 6. From the test results, the chemical composition of the oil pipe meets the requirements for technology standard.

Table 6.

Chemical composition analysis results (wt%).

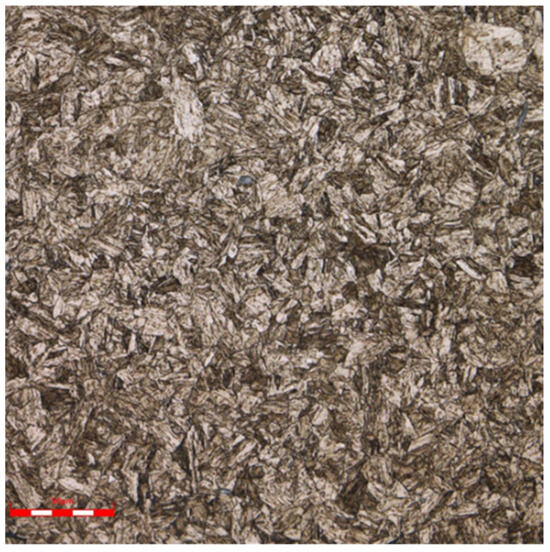

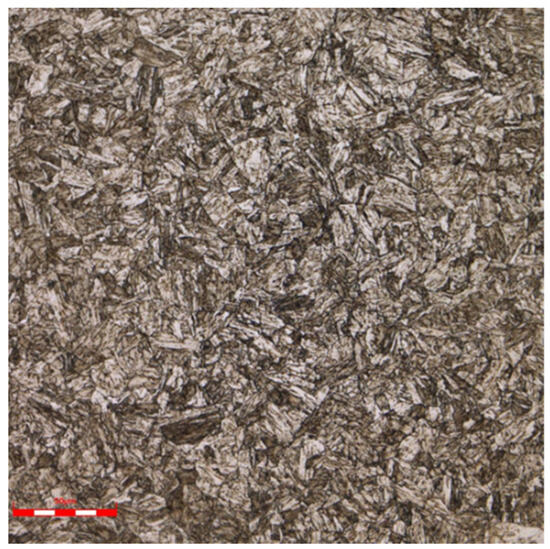

7. Metallographic Structure Analysis

The sample preparation procedure mainly includes sampling, mounting, grinding, polishing, and corrosion. After the metallographic sample is made, it can be observed under an optical microscope to observe the sample structure and cracks. The microstructure, grain size, and non-metallic inclusions were analyzed using a focusing microscope (an optical microscope). The analysis results are shown in Table 7. The photos of the metallographic structure are shown in Figure 7 and Figure 8. The results show that the structure of the failed oil pipe body and the surrounding cracks are all Mshaped with no obvious structural transformation, the non-metallic inclusions are normal, and the grain size is 9.5.

Table 7.

Metallographic structure test results.

Figure 7.

1# oil pipe body structure (50 μm).

Figure 8.

2# oil pipe body structure (50 μm).

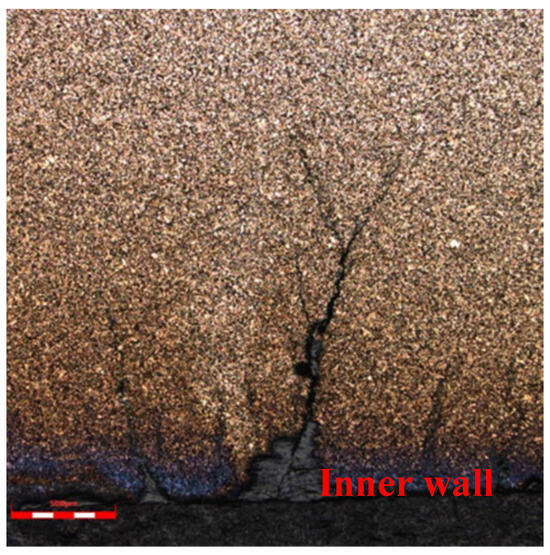

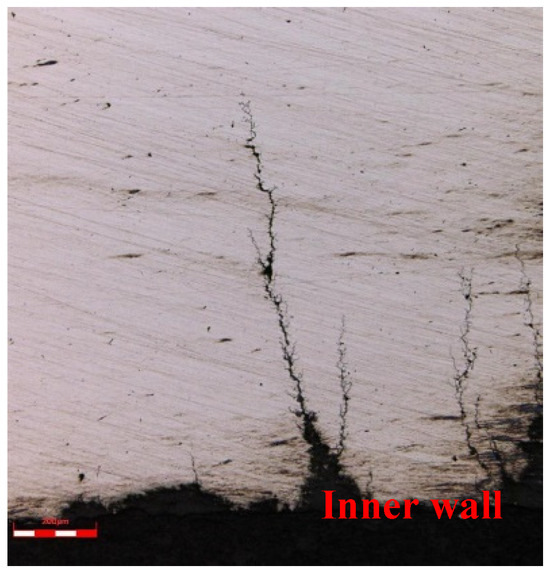

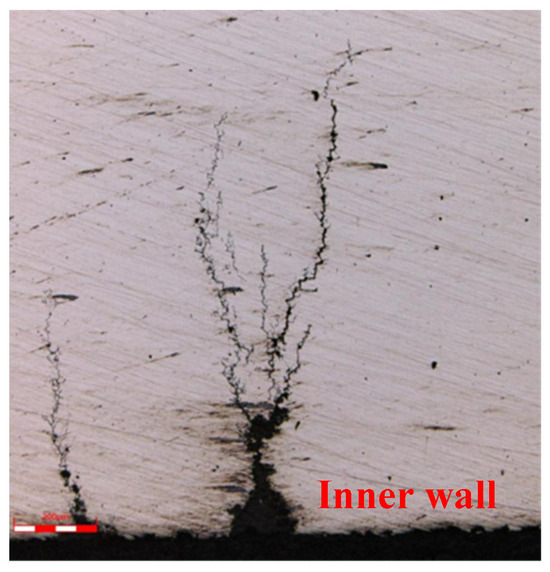

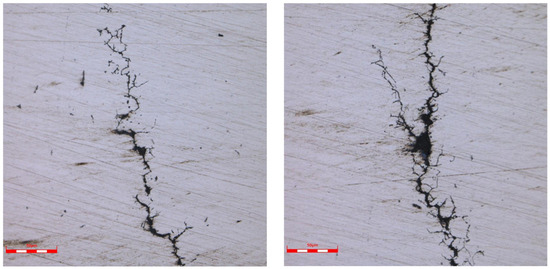

The crack morphology and the photos of the surrounding tissue are shown in Figure 9, Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12, Figure 13 and Figure 14. The crack originated from the bottom of the corrosion pit on the inner wall, expanded along the wall thickness direction, and had intergranular cracking characteristics. The crack expanded in the middle and late stages in the shape of a tree, with secondary cracks, and there was no abnormality in the structure around the crack. The scale of Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 9 and Figure 10 is 50 times, Figure 11 is 100 times, Figure 12 is 500 times, and Figure 13 and Figure 14 is 200 times.

Figure 9.

Intergranular cracking on the inner surface of 1# oil pipe (50 μm).

Figure 10.

The tip of the crack on the inner surface of the 1# oil pipe is split (100 μm).

Figure 11.

Crack morphology on the inner surface of 1# oil pipe (local crack 1) (500 μm).

Figure 12.

Crack morphology on the inner surface of 1# oil pipe (local crack 2) (200 μm).

Figure 13.

Crack morphology on the inner surface of 1# oil pipe (local crack 3) (200 μm).

Figure 14.

Crack tip morphology on the inner surface of 1# oil pipe (50 μm).

8. Mechanical Property Test

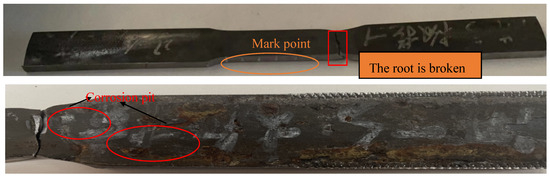

According to the GB/T 228.1-2021 standard [17], longitudinal tensile specimens were taken from the failed oil pipe body, 3 groups were taken from the 1# oil pipe, and 3 groups were taken from the 2# oil pipe, for a total of 6 groups; longitudinal Charpy V-type specimens were taken according to GB/T229-2020 [18]. For notched impact specimens, 3 groups were taken from 1# oil pipe and 3 groups from the 2# oil pipe for a total of 6 groups; according to GB/T 230.1-2018 [19], the full-wall thickness hardness ring samples must be taken from 2 groups from 1# oil pipe and 2 groups from 2# oil pipe. Two groups, four groups in total must undergo a tensile property test; the Charpy impact and hardness test were also conducted, respectively. The test results are shown in Table 8, Table 9 and Table 10. The test results show that the 1# oil pipe No. 3 sample was broken at the root but not at the marked point, and the elongation after break did not meet the requirements. After macroscopic observation of the sample, as shown in Figure 15, the inner surface of the sample has corrosion pits that affect the tensile properties of the oil pipe, so the post-break elongation of the No. 3 test of the 1# oil pipe is only for reference to look at the tensile performance parameters of the three samples from the 2# non-fracture oil pipe.

Table 8.

Tensile test results.

Table 9.

Charpy impact test results.

Table 10.

Rockwell hardness test results.

Figure 15.

(Above) Tensile properties test of sample 1# oil pipe No. 3. (Below). Corrosion on the inner surface of sample 1# oil pipe No. 3.

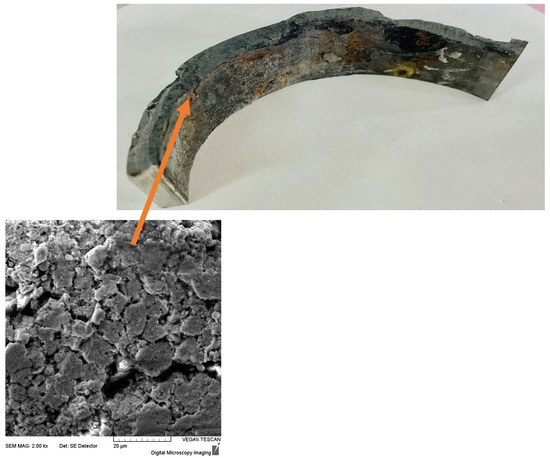

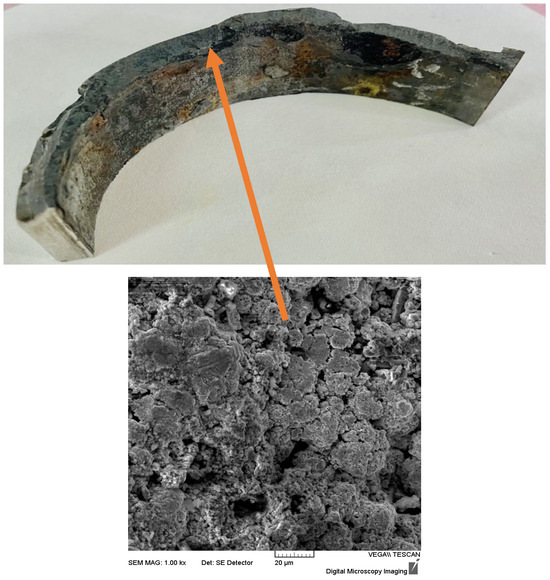

9. Microanalysis

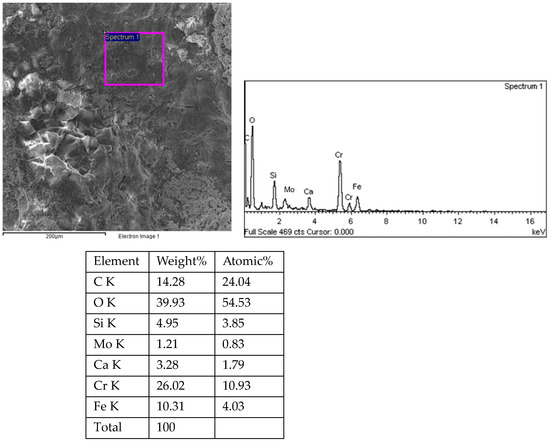

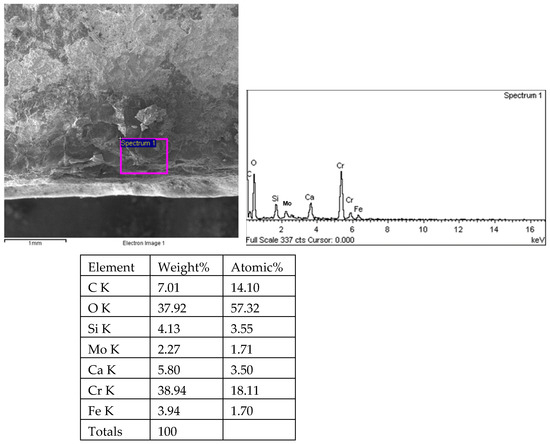

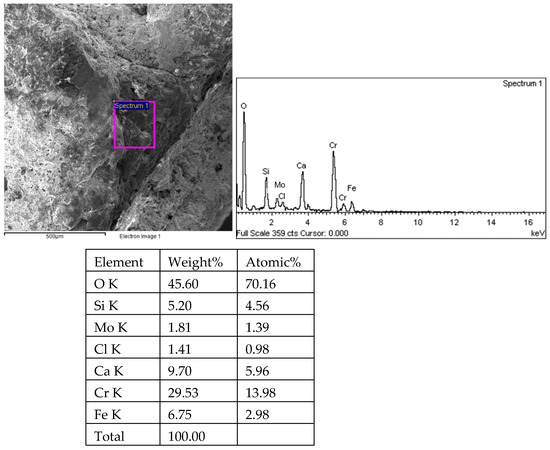

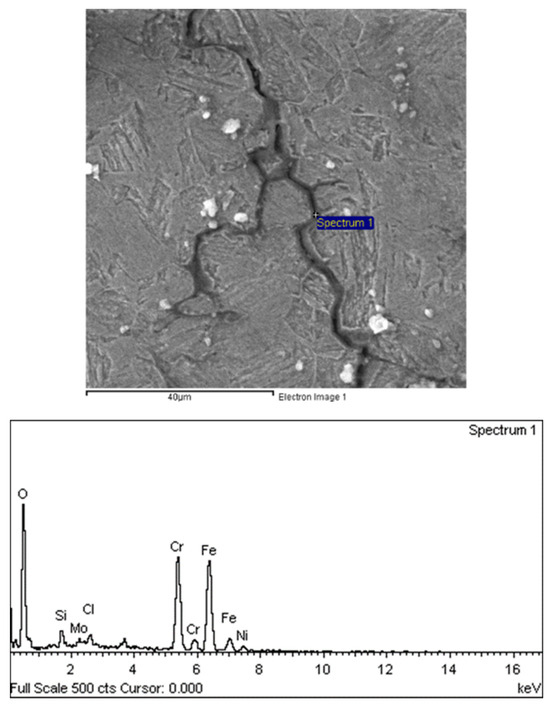

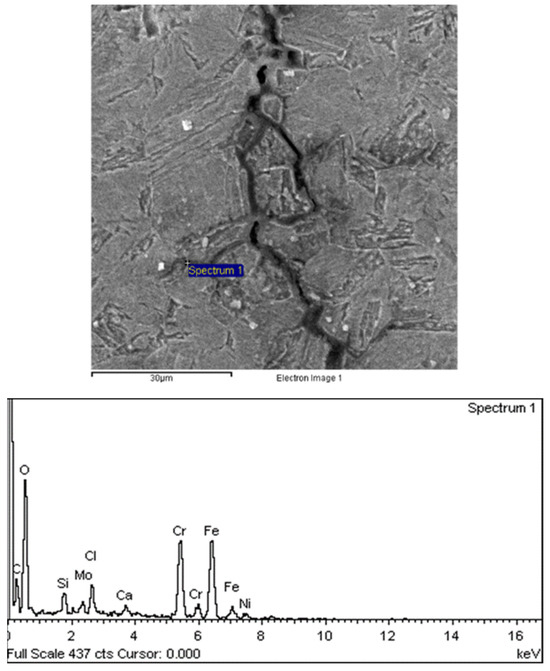

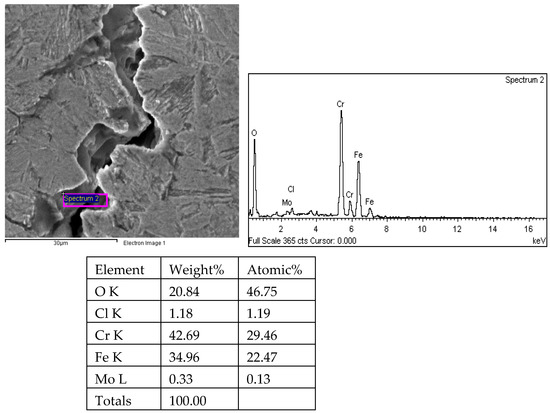

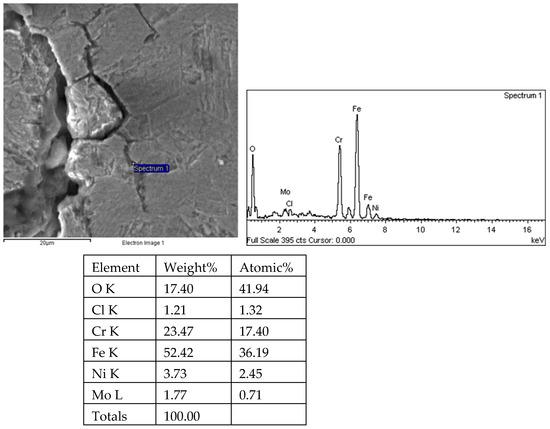

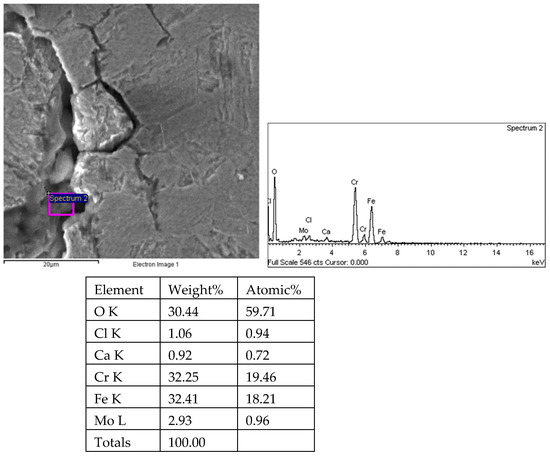

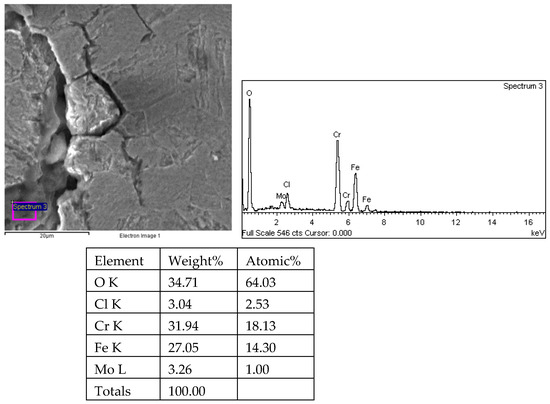

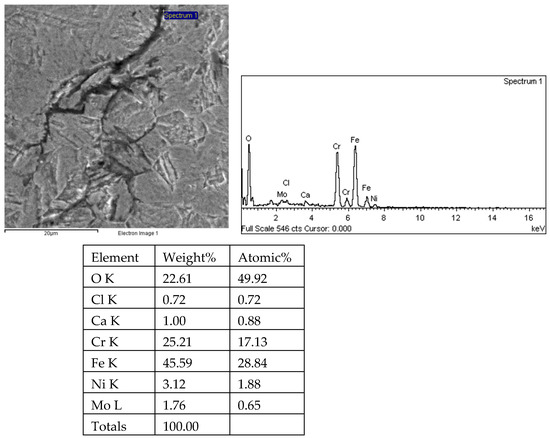

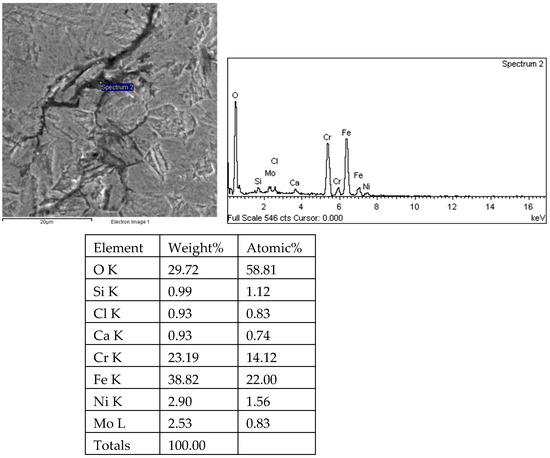

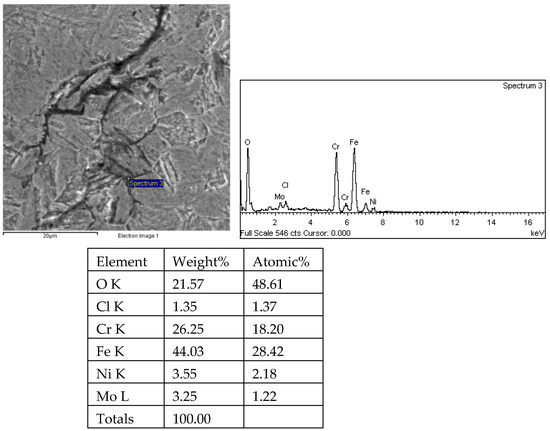

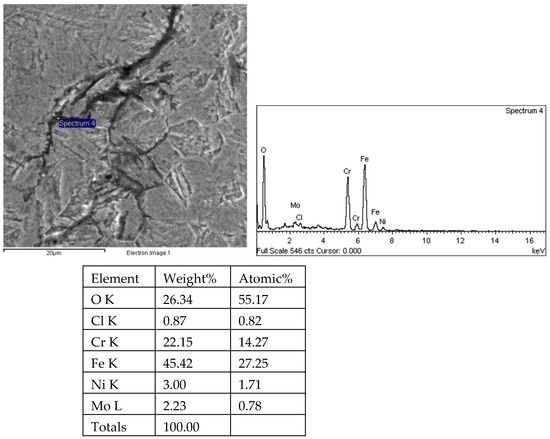

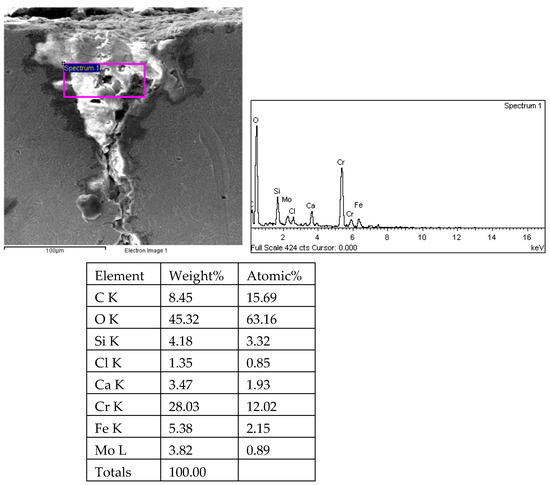

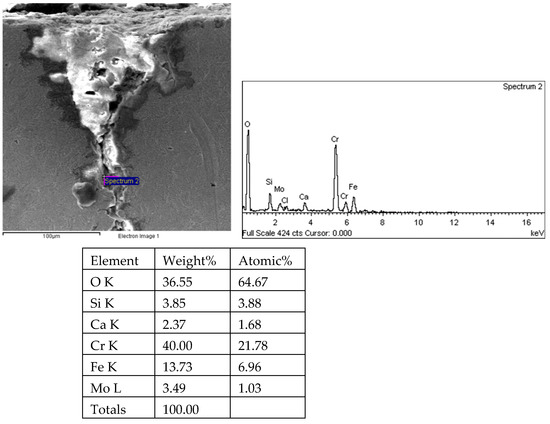

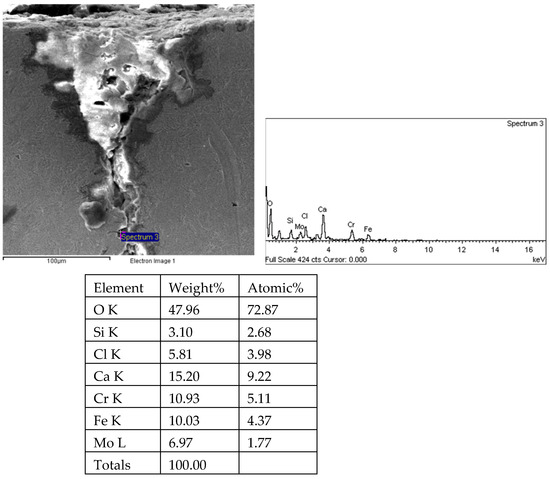

Sampling was taken from the fracture surface of the 1# oil pipe, which was cleaned with acetate fiber paper and ultrasound. The morphology and energy spectrum analysis of the fracture surface and the surrounding inner surface of the pipe were observed and analyzed using the TESCAN VEGA II scanning electron microscope (Tyscan (China) Co., Shanghai, China) and its accompanying XFORD INCA350 energy spectrum analyzer (Oxford Instruments, Shanghai, China). The fracture surface and crack energy spectrum of 34 pieces were observed under the scanning electron microscope for 35 h. The fracture morphology of the 1# oil pipe is shown in Figure 16, Figure 17 and Figure 18. The fracture position has a relatively flat morphology, with corrosion pits on the right side. There are many intergranular morphologies on the middle and left sides of the fracture. The energy spectrum analysis results of the 1# oil pipe fracture are shown in Figure 18, Figure 19, Figure 20, Figure 21, Figure 22, Figure 23, Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27 and Figure 28. The main components are C, O, Fe, Cr, and Mo elements, followed by Cl, Si, and Ca elements.

Figure 16.

Fracture morphology on the left side of 1#.

Figure 17.

1# middle side fracture morphology.

Figure 18.

Fracture morphology on the right side of 1#.

Figure 19.

Energy spectrum analysis results of corrosion pits at the fracture of 1# oil pipe.

Figure 20.

Energy spectrum analysis results of the middle fracture of 1# oil pipe.

Figure 21.

Energy spectrum analysis results of the middle fracture of 1# oil pipe (anthor detection range).

Figure 22.

Intergranular propagation morphology of oil pipe cracks.

Figure 23.

The morphology of the oil pipe crack along the crystal tip.

Figure 24.

Root morphology and energy spectrum analysis results of crack 1 on the 1# oil pipe body.

Figure 25.

Energy spectrum analysis results of crack 1 propagation in 1# oil pipe body (region 1).

Figure 26.

Results of crack 1 propagation and energy spectrum analysis on the 1# oil pipe body (region 2).

Figure 27.

Results of crack propagation and energy spectrum analysis of 1# oil pipe body (region 3).

Figure 28.

Results of crack propagation and energy spectrum analysis of 1# oil pipe body (region 4).

There are transverse cracks in the 1# oil pipe. According to the metallographic analysis results, it is known that the crack originated from the inner surface of the pipe, as shown in Figure 11. The crack morphology is shown in Figure 22 and Figure 23, and it can be seen that the crack propagates along the grain. In order to further analyze the distribution of elements in the cracks on the inner surface of the oil pipe, energy spectrum analysis was performed on the cracked sample. The energy spectrum analysis results are shown in Figure 24, Figure 25, Figure 26, Figure 27, Figure 28, Figure 29, Figure 30, Figure 31, Figure 32, Figure 33, Figure 34 and Figure 35, which are the root, middle, and tip areas of the three cracks, respectively. The analysis results show that the crack mainly contains C, Fe, Cr, Ni, Mo, O, and Cl elements. The O element in the crack is distributed at each stage of crack growth, with the highest mass fraction reaching 45.60%. In addition, as the crack grows, the Cl element is also always present by extension. There are still Si and Ca in the crack tip. This is because the crack in the pipe body is in an open state due to the influence of tensile stress when it is not disconnected. At the same time, the gas-lift drainage operation is a pressure injection process (see Table 1) that provides both the conditions for sediment (containing Si) and water (containing Ca) to enter the crack. As the crack expands, the tensile performance of the oil pipe decreases and eventually breaks, and the crack closes. Currently, Si and Ca remain in cracks.

Figure 29.

Analysis results of crack 1 tip and energy spectrum of 1# oil pipe body (region 1).

Figure 30.

Energy spectrum analysis results of tip 1 of crack 1 in the 1# oil pipe body (region 2).

Figure 31.

Energy spectrum analysis results of tip 1 of crack 1 in the 1# oil pipe body (region 3).

Figure 32.

Energy spectrum analysis results of 1# oil pipe body crack 1 (region 4).

Figure 33.

Energy spectrum analysis results of crack 2 root of 1# oil pipe body (region 1).

Figure 34.

Root and energy spectrum analysis results of crack 2 on the 1# oil pipe body (region 2).

Figure 35.

Root and energy spectrum analysis results of crack 2 on 1# oil pipe body (region 3).

10. Comprehensive Analysis

The macroscopic observation and analysis of the fracture showed that the fracture of the oil pipe sent for inspection was relatively flat, and the crack originated from the inner wall of the oil pipe; a shear lip was visible on the outside of the fracture, and there was no obvious plastic deformation around the fracture, which is a typical brittle fracture. A microscopic analysis of the fracture showed that the matrix of the fracture had intergranular characteristics, such as transgranular cracks, which have the typical microscopic characteristics of brittle fractures. A metallographic analysis of the crack cross section shows that the cracks are relatively straight along the crystalline shape and branched at the tip. Based on the above characteristics, it can be determined that the fractures and cracks of the oil pipe submitted for inspection have macro and micro characteristics of stress corrosion cracking.

Relevant research shows that three basic conditions need to be met for stress corrosion cracking in oil pipes, namely sensitive metal materials, specific corrosive media, and a certain tensile stress. Combining these three basic conditions, the analysis of the reasons for the oil pipe fracture is as follows:

- (1)

- Sensitive metal materials

The oil pipe is made of super 13Cr steel. This material is based on ordinary 13Cr stainless steel. By reducing the C content in the steel while retaining Cr, which is the key to corrosion resistance of stainless steel, resistance is ensured by adding trace alloy elements such as Mo, Ni, and Cu. This is a steel type that further improves its pitting corrosion resistance without reducing its mechanical properties. It is precisely because of the outstanding performance characteristics of super 13Cr martensitic stainless steel that it is widely used in complex oil and gas production conditions. However, in cases of oil pipe failure, it can be seen that super 13Cr has stress-corrosion-cracking sensitivity in certain media environments.

Research has been conducted on stress corrosion cracking sensitive media for super 13Cr both domestically and internationally. The results show that, in addition to sulfide stress corrosion cracking caused by H2S in low pH environments, martensitic stainless steel also has high sensitivity to Cl− rich solutions [2,4]. When H2S and Cl− are mixed in the environment, its sensitivity to stress corrosion cracking is higher. In addition, in order to improve the efficiency of downhole fluid drainage and enhance oil recovery, nitrogen gas lift, as a simple and low-cost fluid drive technology, is applied in oil and gas production. However, it inevitably introduces the strong corrosive medium O2 that originally did not exist at the bottom of the well into the wellbore environment. At present, it is widely recognized at home and abroad that the synergistic effect of O2 and high concentration Cl− can cause stress corrosion cracking of oil pipes. Dissolved oxygen in the solution not only has strong corrosiveness to carbon steel materials but also a significant promoting effect on stress corrosion cracking of corrosion-resistant alloys such as martensitic stainless steel. API 13TR1, in summarizing the experimental rules of stress corrosion cracking in 13Cr media, indicates that in the CaCl2 inorganic salt environment when dissolved O2 is added, 13Cr pipes cannot pass the SCC test. After removing oxygen, the material will pass the test and will not undergo stress corrosion cracking. In the failure case of the super 13Cr oil pipe in the Tarim Oilfield, the reason for the fracture of the oil pipe in the same block well was the combined use of dissolved O2 and Cl− after acidification was used as the stress-corrosion-cracking medium for the oil pipe.

- (2)

- Specific corrosive media

Most of the stress corrosion cracking of super 13Cr oil pipes mainly occurs on the outer surface of the pipes, such as environmental fractures caused by phosphate completion fluid in the oil sleeve annulus. However, the well oil pipe crack that failed this time started from the inner wall, indicating that the produced material underground contains sensitive media that can cause stress corrosion cracking of the pipes. According to the investigation of the sampling composition and nitrogen gas-lift drainage situation at the wellhead, it is known that the formation water belongs to the high salinity CaCl2 water type (see Table 4). The well underwent gas-lift drainage operations three times before and after April 2013, October 2017, and August 2019, and O2 was detected at the wellhead, gas gathering station, and the outlet of the medium pressure metering separator (see Table 3) (the same block was subjected to gas lift drainage and injected with oxygen-containing nitrogen gas, with an oxygen content of about 3% to 5%). According to the requirements, the nitrogen content is more than 99.2% and the oxygen content is less than 0.8%. A large number of experimental statistical results have found that O and Cl elements, which cause stress corrosion cracking, are found on the source and propagation areas of the fracture, as well as on the inner surface of the pipe near the fracture. The synergistic effect of the two elements promotes the cracking.

- (3)

- A certain tensile stress

The force that causes stress corrosion cracking is generally tensile stress, and the formation and propagation of cracks are roughly perpendicular to the direction of tensile stress, which can be confirmed by the fracture of the oil pipe perpendicular to the axial direction. During the downhole service of the oil pipe, due to the gravity effect of the pipe string, it must bear considerable axial tensile load, thus providing stress conditions for stress corrosion cracking.

The well underwent a string replacement operation in 2008, and the fractured oil pipe was located at the wellhead. Therefore, the pipe body at the crack location was subjected to high tensile stress, resulting in fracture.

11. Conclusions and Recommendations

- (1)

- The microscopic analysis of crack metallography shows that the crack originates from the inner wall of the oil pipe, extends along the crystal, and has branching at the tip, belonging to stress corrosion cracking.

- (2)

- The synergistic effect of Cl− and oxygen during gas lift drainage is an important reason for the stress corrosion cracking of the oil pipe. The failed oil pipe is located at the wellhead, where it is subjected to significant axial tensile stress and causes fractures.

- (3)

- It is recommended to strictly control the oxygen content in gas-lift operations and reduce the sensitivity of super 13Cr pipes to stress corrosion cracking.

- (4)

- The methods to reduce the susceptibility of super-13Cr steel to stress corrosion cracking (SCC) can be analyzed and implemented from multiple perspectives.

- ①

- Material composition optimization

- (1)

- Increase the content of molybdenum (Mo): molybdenum can significantly improve the material’s resistance to pitting and crevice corrosion, thus indirectly reducing SCC susceptibility.

- (2)

- (Adding trace elements: adding elements such as niobium (Nb), titanium (Ti), and other elements can improve the microstructure of the material, reducing the possibility of intergranular corrosion.

- (3)

- Control of carbon content: Low or ultra-low carbon design can reduce carbide precipitation, thereby reducing the risk of intergranular corrosion.

- ②

- Heat treatment process optimization

- (1)

- Solution treatment: Through high-temperature solution treatment, the residual stresses generated during welding or machining can be eliminated, and the grain can be refined to improve the toughness and corrosion resistance of the material.

- (2)

- Control the cooling rate: rapid cooling prevents precipitation of brittle phases (e.g., σ-phase) and thus reduces the material’s brittleness.

- (3)

- Avoid the chemical sensitization temperature interval: in the heat treatment process, prolonged exposure of the material to the sensitization temperature interval must be avoided to prevent intergranular corrosion from occurring.

- ③

- Environmental control

- (1)

- Reduce the concentration of corrosive media: reduce the concentration of corrosive media such as chloride ions and hydrogen sulfide in the environment by dilution or filtration.

- (2)

- Control temperature and pH: Avoid the prolonged use of the materials at high temperatures or extreme pH environments.

- (3)

- Regular cleaning of deposits: Prevent crevice corrosion from occurring, especially in areas where deposits may be present.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.X.; methodology, K.X.; supervision, S.X., J.L. and B.W.; validation, S.X., J.L. and B.W.; writing—original draft, K.X.; writing—review and editing, K.X. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The authors are grateful to the fund support of the Scientific research and technology development project of CNPC: Research on safety assessment technology of injection production conversion process in gas storage (KT2020-16-06).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Wang, Z.; Wang, P.; Zeng, D.; Shi, T.; Deng, W. A study on the influential factors of stress corrosion cracking in C110 casing pipe. Materials 2022, 15, 801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, J.; Zhong, X.; Xiong, Q.; Yu, J.; Hou, D.; Wang, Z.; Shi, T. Pitting Corrosion of S13Cr Tubing in a Gas Field: A Failure Case and Corrosion Mechanism Analysis. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2024, 24, 331–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zheng, Y.; Li, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, M.; Gao, W.; Shi, T. Stress corrosion crack evaluation of super 13Cr tubing in high-temperature and high-pressure gas wells. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2019, 95, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, N.; Zhao, M.; Wu, Z.; Wang, P.; Feng, C.; Xie, J.; Long, Y.; Song, W.; Xiong, M. Collapse failure analysis of S13Cr-110 tubing in a high-pressure and high-temperature gas well. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 148, 107187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K.; Shukla, S.; Verma, A. Fracture Toughness of 41XX Cr-Mo Steel, Super Martensitic Stainless Steel and Nickel Alloy in High Pressure Hydrogen Environment. In Proceedings of the AMPP Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3–7 March 2024; p. AMPP-2024-21083. [Google Scholar]

- Kamo, Y.; Ishiguro, Y.; Mizuno, Y. Environmentally-Assisted Cracking (SSC and SCC) of Martensitic Stainless Steel OCTG Material in Sour Environment in 5% NaCl and 20% NaCl Solution. In Proceedings of the AMPP Annual Conference & Expo 2022, San Antonio, TX, USA, 6–10 March 2022; p. D031S021R006. [Google Scholar]

- Yue, X.; Huang, L.; Qu, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zhang, L.; Hua, Y. Formation and Evolution of the Corrosion Scales on Super 13Cr Stainless Steel in a Formate Completion Fluid with Aggressive Substances. Front. Mater. 2022, 8, 802136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mubarak, G.; Elkhodbia, M.; Gadala, I.; AlFantazi, A.; Barsoum, I. Failure analysis, corrosion rate prediction, and integrity assessment of J55 downhole tubing in ultra-deep gas and condensate well. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2023, 151, 107381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, Y.; Li, C.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, F.; Xiang, Y. Crevice Corrosion Mechanism of L80-13cr in Cl-Containing Supercritical CO2 Water-Rich Phase Considering the Influence of SO2. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5067762 (accessed on 11 February 2025).

- Giarola, J.M.; Santos, B.A.F.; Souza, R.C.; Serenario, M.E.D.; Martelli, P.B.; Souza, E.A.; Gomes, J.A.C.P.; Bueno, A.H.S. Proposal of a novel criteria for soil corrosivity evaluation and the development of new soil synthetic solutions for laboratory investigations. Mater. Res. 2022, 25, e20210521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Huang, X.; Song, W.; Huang, C.; Liu, H.; Wang, H. Multi-factor corrosion model of TP110TS steel in H2S/CO2 coexistence and life prediction of petroleum casings. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2024, 209, 105204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, B.J.C.; Al Kindi, M.; Braiki, A.S. Non Producing Environments Leading to Downhole CRA Completion Failures. In Proceedings of the AMPP Annual Conference, New Orleans, LA, USA, 3–7 March 2024; p. AMPP-2024-20620. [Google Scholar]

- Qi, W.; Gao, Q.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, T.; Wang, F. Insight into the stress corrosion cracking of HP-13Cr stainless steel in the aggressive geothermal environment. Corros. Sci. 2021, 190, 109699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yue, X.; Cao, H.; Zhang, L.; Lu, M.; Ma, L.; Zhao, M.; Hua, Y. Effect of Aggressive Substance on the Nature of Corrosion Scales Formation on Super 13Cr Stainless Steel in Formate Completion Fluid. In Proceedings of the NACE Corrosion, Virtual, 19–30 2021; p. D081S030R001. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, S.; Fu, A.; Liu, M.; Xue, Y.; Lv, N.; Han, Y. Stress corrosion cracking behavior and mechanism of super 13Cr stainless steel in simulated O2/CO2 containing 3.5 wt% NaCl solution. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 130, 105748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 11170; Stainless Steel—Determina of Multi-Element Contents—Spark Discharge Atomic Emission Spectrometric Method (Routine Method). National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2008.

- GB/T 228.1; Metallic Materials—Tensile Testing—Part 1: Method of Test at Room Temperature. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- GB/T 229; Matallic Materials—Charpy Pendulum Impact Test—Part 1: Test Method, MOD. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2020.

- GB/T 230.1; Metallic Materials—Rockwell Hardness Test—Part 1: Test Method. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2018.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).