A Study on the Impact of Energy Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. An Overview of the Impact of Diplomatic Activities on Energy Trade Cooperation

3. Background of Model and Parameter Descriptions

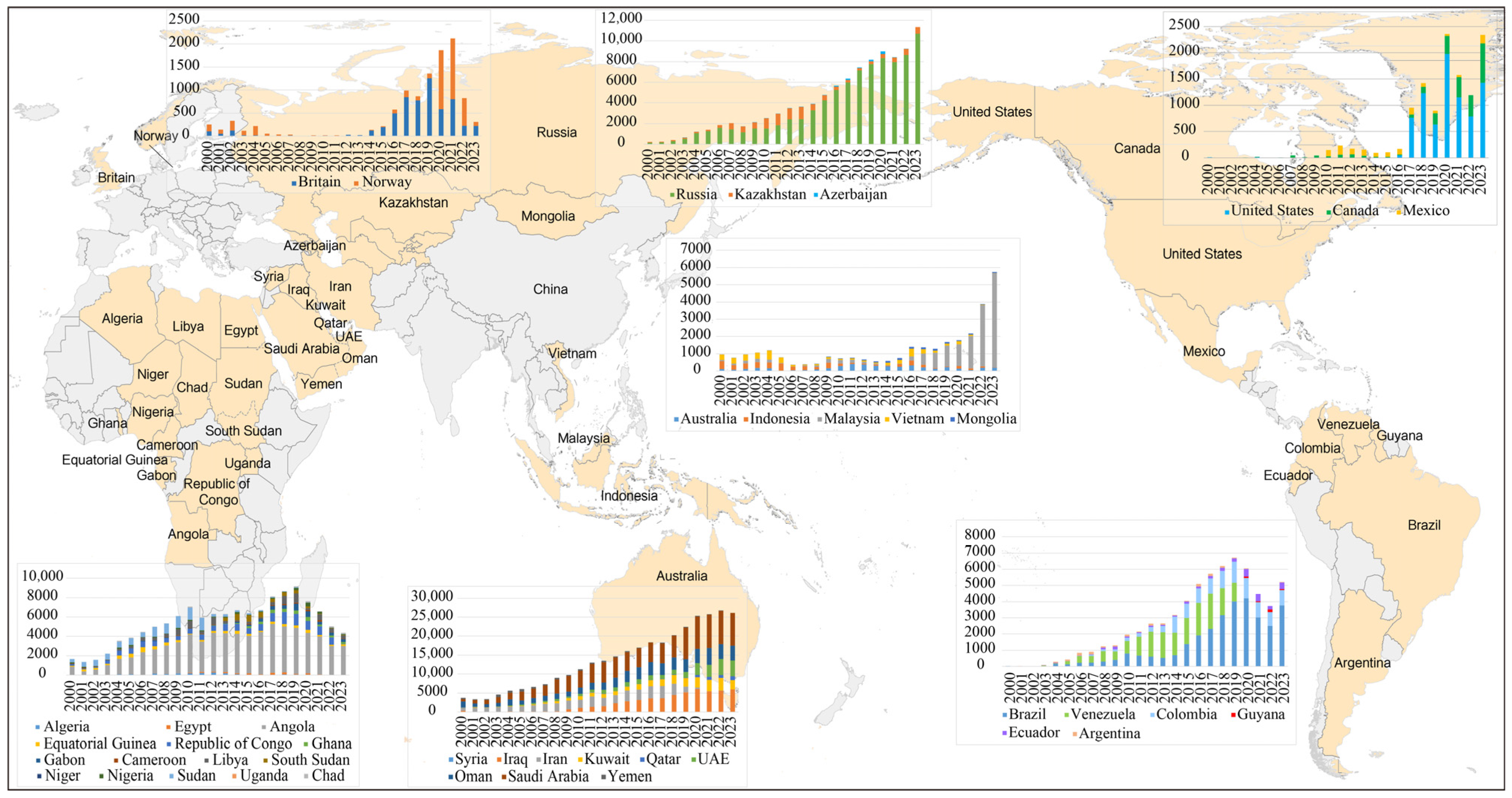

3.1. Characteristics of China’s Crude Oil Trade

3.2. Characteristics of China’s Energy Diplomacy

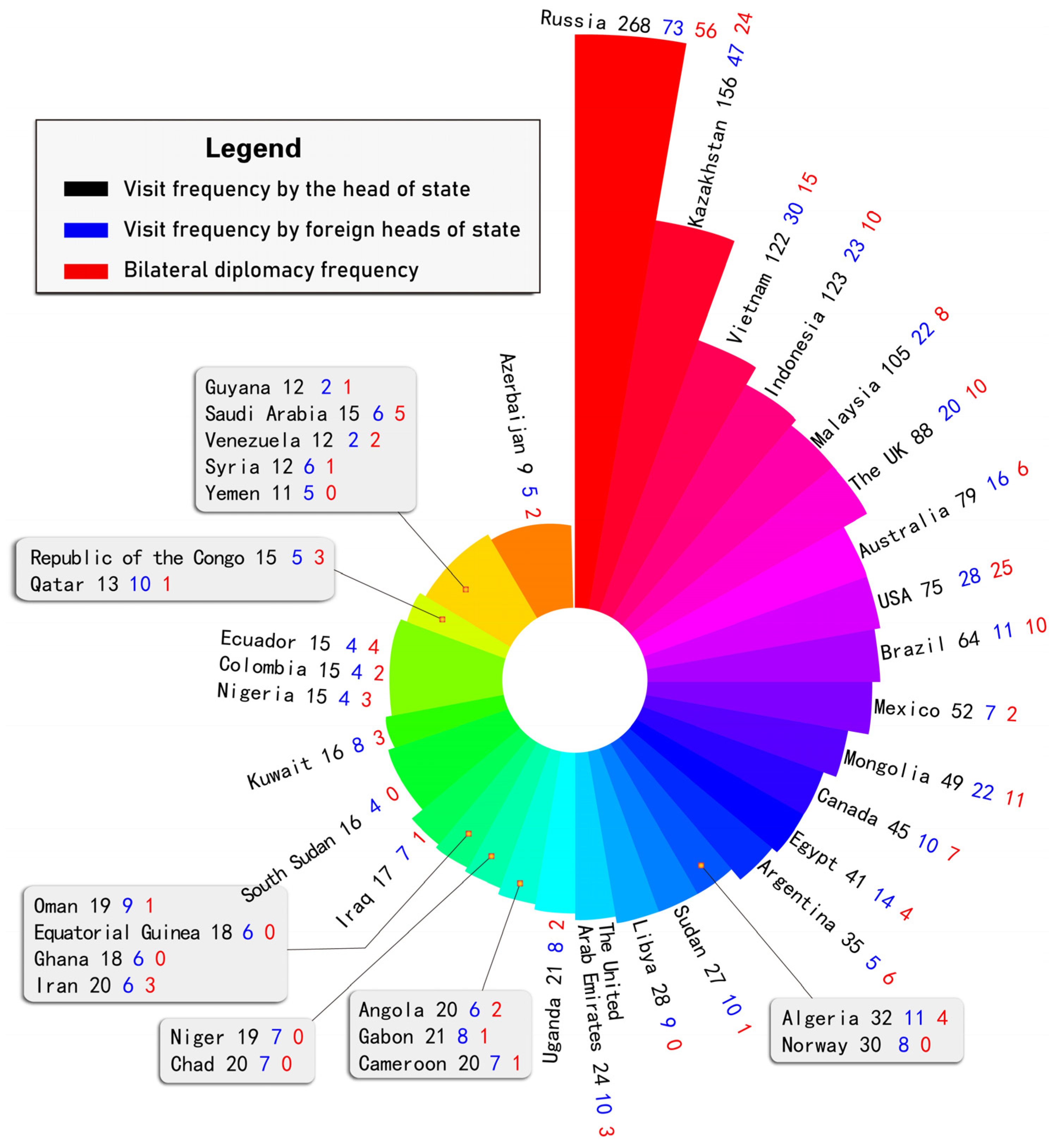

3.2.1. Overview of China’s Energy Diplomacy

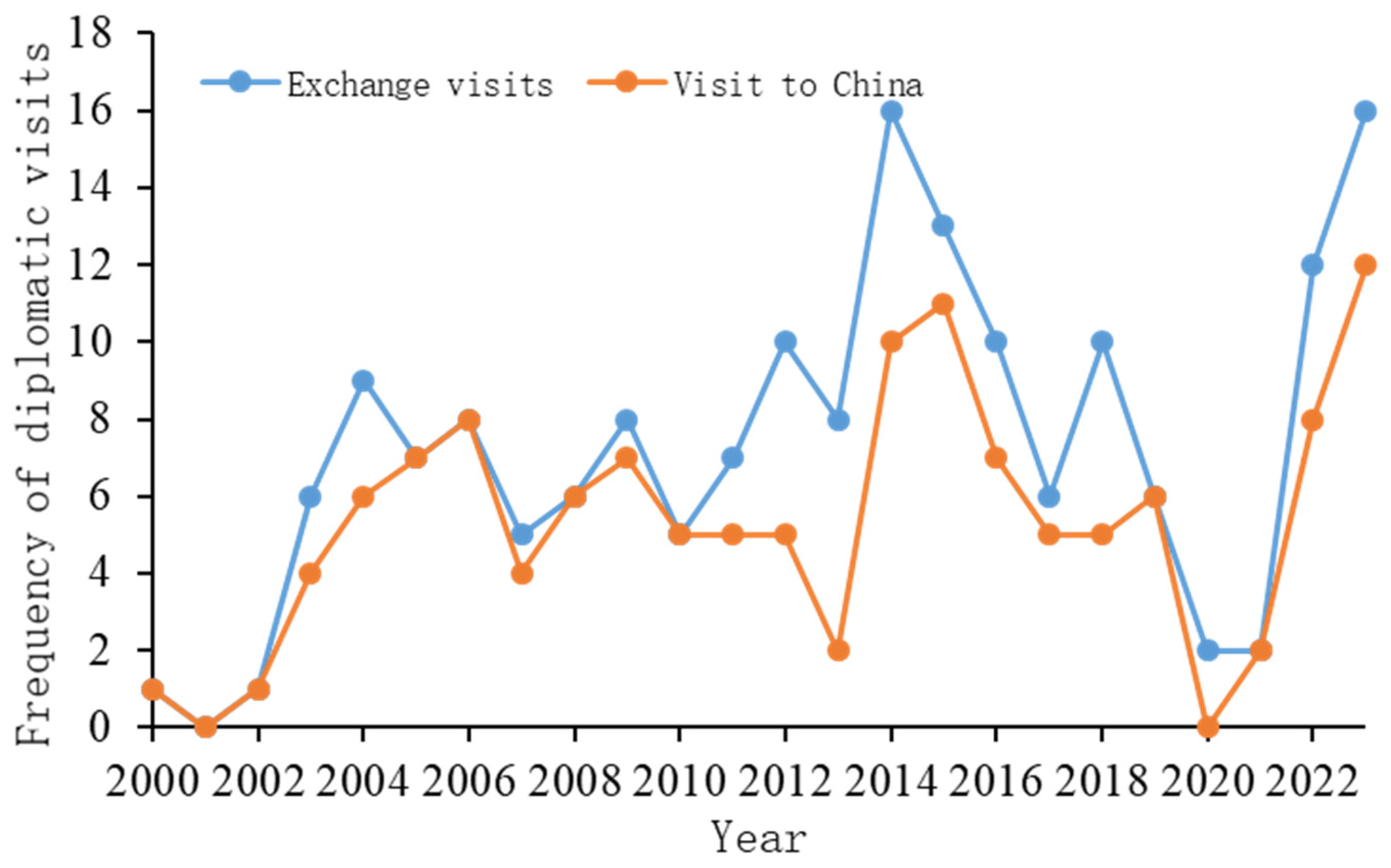

3.2.2. Frequency of Bilateral Mutual Visits and Incoming Visits

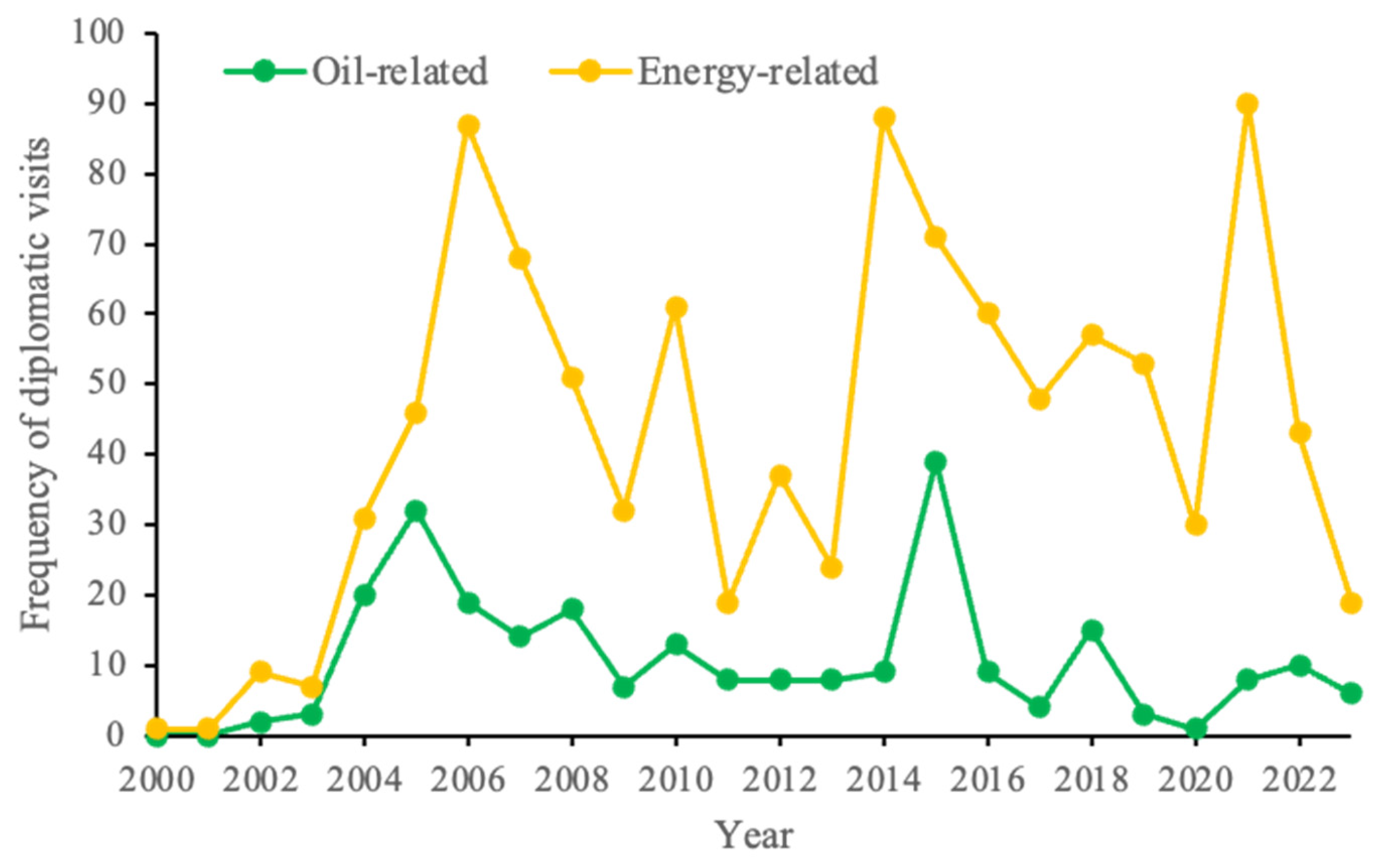

3.2.3. Characteristics of Joint Statements Related to Energy Diplomacy

- (1)

- Enhancement of Strategic Cooperative Partnership

- (2)

- Joint statement involving the energy or petroleum fields

3.3. Basic Assumptions

3.4. Parameter Descriptions

3.5. Econometric Model

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Main Regression and Various Factors Influencing China’s Crude Oil Trade

4.1.1. Impact of the Frequency of Meetings Between the Heads of State on Crude Oil Trade

4.1.2. Impact of the First Meetings Between the Heads of State on Crude Oil Trade

4.1.3. Impact of Diplomatic Relation Level Upgrade on Crude Oil Trade

4.1.4. Impact of Joint Statements Involving Petroleum Cooperation on Crude Oil Trade

4.1.5. Impact of Foreign Visits on China’s Crude Oil Trade

4.1.6. Impact of Bilateral Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade

4.2. Heterogeneity Test

4.2.1. Impact of Diplomacy with “One Belt and One Road” Countries on Crude Oil Trade

4.2.2. Impact of Diplomacy with Neighboring Countries on Crude Oil Trade

5. Conclusions and Suggestions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Countries | Levels of Diplomatic Relations | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Russia | Deepening Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2010 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership New Level | 2014 | |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership in New era | 2019 | |

| Kazakhstan | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2011 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership New Level | 2015 | |

| Permanent Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2019 | |

| The United Arab Emirates | Strategic Partnership | 2012 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2018 | |

| Ecuador | Strategic Partnership | 2015 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2016 | |

| Argentina | Strategic Partnership | 2004 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2014 | |

| Iran | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2016 |

| Iraq | Strategic Partnership | 2015 |

| Saudi Arabia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2016 |

| Qatar | Strategic Partnership | 2014 |

| Kuwait | Strategic Partnership | 2018 |

| Oman | Strategic Partnership | 2018 |

| Egypt | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2016 |

| Algeria | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2014 |

| Sudan | Strategic Partnership | 2015 |

| Uganda | Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership | 2019 |

| Nigeria | Strategic Partnership | 2006 |

| Angola | Strategic Partnership | 2010 |

| Republic of the Congo | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2016 |

| Equatorial Guinea | Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership | 2015 |

| Gabon | Comprehensive Cooperative Partnership | 2016 |

| Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2023 | |

| Canada | Strategic Partnership | 2005 |

| Mexico | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2013 |

| Venezuela | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2014 |

| Round-the-Clock Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2023 | |

| Brazil | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2012 |

| Australia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2014 |

| Indonesia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2013 |

| Malaysia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2013 |

| Malaysia | Comprehensive Strategic Cooperative Partnership | 2008 |

| Mongolia | Comprehensive Strategic Partnership | 2014 |

| Britain | Global Comprehensive Strategic Partnership toward the 21st Century | 2015 |

| Norway | Normalizing the Bilateral Relations | 2016 |

| South Sudan | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 2011 |

| Chad | Reestablish Diplomatic Relations | 2006 |

| Yemen | Friendly and Cooperative Relations | before 2010 |

| Syria | Friendly and Cooperative Relations | before 2010 |

| Strategic Partnership | 2023 | |

| America | Constructive Strategic Partnerships | 1997 |

| New Model of Major Power Relationship | 2015 | |

| Niger | Reestablishing Diplomatic Relations | 1996 |

| Azerbaijan | Friendly and Cooperative Relations | before 1994 |

| Colombia | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 1980 |

| Strategic Partnership | 2023 | |

| Libya | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 1978 |

| Guyana | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 1972 |

| Cameroon | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 1971 |

| Ghana | Establishing Diplomatic Relations | 1960 |

References

- Wang, J.; Cao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Rao, J. Ensuring energy security in China through international energy cooperation. Strateg. Study CAE 2021, 23, 118–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; Wang, J.; Yuan, X.; Wang, S.; Shao, Q.; Hu, J. Bilateral political relations and the security of China’s energy imports. Energy Explor. Exploit. 2024, 42, 789–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Wu, L. Global energy governance transformation and China’s strategic choice. J. Zhejiang Univ. Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2024, 54, 30–40. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, E.; Steven, T.L. The stabilizing effects of international politics on bilateral trade flows. Foreign Policy Anal. 2015, 11, 151–171. [Google Scholar]

- Chia-yi, L. China’s energy diplomacy: Does Chinese foreign policy favor oil-producing countries? Foreign Policy Anal. 2019, 15, 570–588. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.C.; Fuchs, A.; Johnson, K. State control and the effects of foreign relations on bilateral trade. J. Confl. Resolut. 2019, 63, 405–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, L.; Lei, J.; Singh, G.; Federico, R. Peace engineering in practice: China’s energy diplomacy strategy and its global implications. Sustainability 2023, 15, 1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gökçe, Z.O.; Hatipoglu, E.; Belaïd, F. Navigating energy diplomacy in times of recovery and conflict: A study of cross-border energy trade dynamics. Resour. Policy 2024, 90, 104850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xin, B.; Zhang, M. Evolutionary game on international energy trade under the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Energy Econ. 2023, 125, 106827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S. Energy diplomacy in a time of energy transition. Energy Strategy Rev. 2019, 26, 100386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grossman, G.M.; Helpman, E. Trade wars and trade talks. J. Political Econ. 1995, 103, 675–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitra, D. Endogenous lobby formation and endogenous protection: A long-run model of trade policy determination. Am. Econ. Rev. 1999, 89, 1116–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alesina, A.; Spolaore, E.; Wacziarg, R. Economic integration and political disintegration. Am. Econ. Rev. 2000, 90, 1276–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, D.; Easterly, W.; Nunn, N.; Satyanath, S. Commercial imperialism? Political influence and trade during the cold war. Am. Econ. Rev. 2013, 103, 863–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, K. Does political conflict hurt trade? Evidence from consumer boycotts. J. Int. Econ. 2016, 99, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yakop, M.; Bergeijk, V.G.A.P. Economic diplomacy, trade and developing countries. Camb. J. Reg. Econ. Soc. 2011, 4, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moons, V.J.S.; Bergeijk, G.A.P. Does economic diplomacy work? A meta-analysis of its impact on trade and investment. World Econ. 2017, 40, 336–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferguson, S.; Forslid, R. Sizing up the impact of embassies on exports. Scand. J. Econ. 2019, 121, 278–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincus, V.C.; Carballo, J. Is export promotion effective in developing countries? Firm-level evidence on the intensive and the extensive margins of exports. J. Int. Econ. 2008, 76, 89–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, V. State visits and international trade. World Econ. 2007, 30, 1797–1816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Head, K.; Ries, J. Do trade missions increase trade? Can. J. Econ. Rev. Can. D’economique 2010, 43, 754–775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeo, T.; Lee, M. Presidential diplomacy and international trade: A case of Korea. J. Korea Trade 2009, 13, 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Lien, D.; Lo, M.; Bojanic, D. Asymmetric effects of cultural institutes on trade and foreign direct investment. World Econ. 2019, 42, 1520–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Demir, F.; Im, H. Effects of cultural institutes on bilateral trade and FDI flows: Cultural diplomacy or economic altruism? World Econ. 2020, 43, 2463–2489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Zhang, Q. China’s foreign economic and trade relations and diplomatic layout. Q. J. Int. Politics 2010, 25–48. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, Y.; Li, Q. Research on the promoting effect of foreign relations on bilateral trade. Dongyue Trib. 2013, 34, 151–157. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, X.; Tian, X. Trade creation effects of diplomatic visits: Evidence from China. J. Int. Trade 2017, 6, 15–26. [Google Scholar]

- He, Z.; Liang, X.; Chen, Y. Diplomatic visits, imports of extrusion and welfare of enterprises. J. Int. Trade 2019, 11, 88–99. [Google Scholar]

- Florini, A.; Sovacool, K.B. Who governs energy? The challenges facing global energy governance. Energy Policy 2009, 37, 5239–5248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graaf, D.V.T.; Colgan, J. Global energy governance: A review and research agenda. Palgrave Commun. 2016, 2, 15047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luomi, M. Is the Paris Agreement a success and what does it mean for the energy sector? Oxf. Energy Forum 2017, 105, 4–7. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, S. Renewable energy policy trends and recommendations for GCC countries. Energy Transit 2017, 1, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, S. A review and assessment of energy policy in the Middle East and North Africa region. Energy Policy 2017, 102, 249–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollins, B.M. Does trade still follow the flag? Am. Political Sci. Rev. 1989, 8, 465–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitsch, V. Honey, I shrunk the currency union effect on trade. World Econ. 2002, 25, 457–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, K.A. The foreign service and foreign trade: Embassies as export promotion. World Econ. 2007, 30, 22–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martincus, V.C.; Estevadeordal, A.; Gallo, A.; Gallo, A.; Luna, J. Information barriers, export promotion institutions, and the extensive margin of trade. Rev. World Econ. Weltwirts Chaftliches Arch. 2010, 146, 91–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacques, M. Does a Country Need a Promotion Agency to Attract Foreign Direct Investment? A Small Analytical Model Applied to 58 Countries; Policy, Research working paper series; no. WPS 3028; World Bank Group: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Gil, S.; Llorca, R.; Serrano, M.A.J. Measuring the impact of regional export promotion: The Spanish case. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2008, 87, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q. The Impact of Diplomatic Relations on Bilateral Trade: A Case Study of China. Master’s Thesis, China Foreign Affairs University, Beijing, China, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, X. A Study on the Influence of Political Diplomacy on China’s Bilateral Trade Flows. Master’s Thesis, Anhui University of Finance and Economics, Bengbu, China, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Shao, Y.; Qiao, H.; Wang, S. What determines China’s crude oil importing trade patterns? Empirical evidences from 55 countries between 1992 and 2015. Energy Policy 2017, 109, 854–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Trade Tracker. The Swiss Army Knife for Global Trade Flows. 2023. Available online: https://www.globaltradetracker.com (accessed on 1 January 2024).

- Du, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Diao, X.; Chen, H. New pattern and trends of global crude oil trade under turbulent situations. Int. Pet. Econ. 2023, 31, 50–59. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, S.; Hao, L.; Tang, W.; Cui, P.; Wu, F. The evolution of competition and cooperation in world crude oil flows from the perspective of complex networks and its enlightenment to China’s oil cooperation. J. Nat. Resour. 2020, 35, 2655–2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, S. Risk and management analysis of China’s petroleum import and export trade. Mod. Econ. Inf. 2019, 12, 160. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, L.; Gao, Q. Trade facilitation, neighboring effects and bilateral agricultural exports—Empirical research based on spatial models of China and neighboring countries. World Agric. 2020, 04, 66–77. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhou, J.; Zeng, X. Mutualism effect of industrial transfer between China and the Belt and Road countries. China Ind. Econ. 2023, 02, 55–73. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Sun, X.; Li, J.; Chen, J.; Liu, C. Has China’s oil-import portfolio been optimized from 2005 to 2014? A perspective of cost–risk tradeoff. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2018, 126, 451–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Kong, G.; Li, Z.; Ma, L.; Ni, W. Strategic analysis of global energy transition and China’s energy revolution. Strateg. Study CAE 2021, 23, 15–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, B.; Cai, T. Has China’s oil investment in Belt and Road initiative countries helped its oil import? Energies 2020, 13, 3176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Niu, X.; Ke, W.; Yu, Z. Investigating the energy trade networks in the Belt and Road regions: Structures and evolution. Energy 2023, 283, 129157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, M.; Duan, Y. Research on oil and gas energy cooperation between China and Central-North Asian countries under the “One Belt and One Road” strategy. Energies 2023, 16, 7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, X.; Chen, W.; Wang, N. Spatiotemporal dynamics and topological evolution of the global crude oil trade network. Energies 2023, 16, 1728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berdysheva, S.; Ikonnikova, S. The energy transition and shifts in fossil fuel use: The study of international energy trade and energy security dynamics. Energies 2021, 14, 5396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Topic | Variable Factors | References |

|---|---|---|

| The impact of political factors on international trade | Political relations (pressure, motivation, etc.) | [11,12,34] |

| Political separatism | [13] | |

| Intervention from relevant government departments | [14] | |

| The impact of overseas institutions on international trade | Political conflicts | [15,35] |

| Overseas embassies | [16,17,18,19,36] | |

| Consulates | [21,22,37] | |

| Overseas trade promotion institutions | [38,39] | |

| Overseas cultural institutions | [23,24] | |

| The impact of diplomatic activities on international trade | State visits, official visits, and visits by heads of state | [26,27,28,35,40] |

| Diplomatic relations, diplomatic levels, diplomatic events, and high-level mutual visits | [40,41] | |

| Bilateral and multilateral diplomacy | [29,30,31,32,33] |

| Countries | NMHS | NV | NTUDL | DCIOG | DCIE | DCMN | NBMDO |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algeria | 32 | 11 | 1 | 4 | 14 | 16 | 4 |

| Argentina | 35 | 5 | 1 | 4 | 18 | 17 | 6 |

| United Arab Emirates | 24 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 15 | 9 | 3 |

| Oman | 19 | 9 | 1 | 4 | 12 | 7 | 1 |

| Azerbaijan | 9 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 3 | 2 |

| Egypt | 41 | 14 | 1 | 3 | 20 | 20 | 4 |

| Angola | 21 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 12 | 8 | 2 |

| Australia | 79 | 16 | 1 | 9 | 47 | 30 | 6 |

| Brazil | 64 | 11 | 1 | 8 | 37 | 27 | 10 |

| Equatorial Guinea | 18 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 0 |

| Russia | 268 | 73 | 3 | 50 | 152 | 109 | 56 |

| Ecuador | 15 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 7 | 4 |

| Republic of the Congo | 15 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 3 |

| Colombia | 15 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 2 |

| Guyana | 12 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 5 | 7 | 1 |

| Kazakhstan | 156 | 47 | 2 | 29 | 90 | 60 | 24 |

| Canada | 45 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 32 | 13 | 7 |

| Ghana | 18 | 6 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 0 |

| Gabon | 21 | 8 | 2 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 1 |

| Cameroon | 20 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 10 | 9 | 1 |

| Qatar | 13 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 9 | 4 | 1 |

| Kuwait | 16 | 8 | 1 | 5 | 10 | 5 | 3 |

| Libya | 28 | 9 | 0 | 2 | 14 | 12 | 0 |

| Malaysia | 105 | 22 | 1 | 11 | 55 | 49 | 8 |

| USA | 75 | 28 | 1 | 21 | 50 | 24 | 25 |

| Mongolia | 49 | 22 | 1 | 7 | 30 | 17 | 11 |

| Mexico | 52 | 7 | 1 | 7 | 32 | 20 | 2 |

| South Sudan | 16 | 4 | 0 | 1 | 8 | 7 | 0 |

| Niger | 19 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Nigeria | 15 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 7 | 3 |

| Norway | 30 | 8 | 0 | 4 | 16 | 13 | 0 |

| Saudi Arabia | 15 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 11 | 4 | 5 |

| Sudan | 27 | 10 | 1 | 3 | 14 | 12 | 1 |

| Venezuela | 12 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 2 |

| Uganda | 21 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 2 |

| Syria | 12 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 6 | 1 |

| Yemen | 11 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 5 | 0 |

| Iraq | 17 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 9 | 8 | 1 |

| Iran | 20 | 6 | 1 | 3 | 11 | 8 | 3 |

| Indonesia | 123 | 23 | 1 | 16 | 70 | 52 | 10 |

| UK | 88 | 20 | 1 | 9 | 54 | 30 | 10 |

| Vietnam | 122 | 30 | 1 | 13 | 68 | 52 | 15 |

| Chad | 20 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Variable Explanation | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent variable | Export_China | Oil export volume to China of certain country in given year | General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China (http://stats.customs.gov.cn/, accessed on 1 July 2024); Economics & Technology Research Institute, CNPC |

| Independent variable | Leader_meet_num | Number of meetings between the leaders of two countries in given year | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (https://www.gov.cn/, accessed on 1 July 2024); Author Compilation |

| First_meet | First meeting between the leaders of two countries or not | ||

| Diplomacy_rank | Whether diplomatic relations between two countries were upgraded or not | ||

| Diplomacy_rank_oil | Joint statement involving oil or not | ||

| Meet_in_China | Number of times the leader of the country visited China in given year | ||

| Two_side | Bilateral diplomacy or not | ||

| Control variable | Export_total | Total oil export volume of country in given year | BP stats review 2023 (https://www.energyinst.org/statistical-review, accessed on 1 July 2024), Global Trade Tracker (http://www.globaltradetracker.com/start/, accessed on 1 July 2024) |

| China_total_import | Total oil import volume of China in given year | General Administration of Customs of the People’s Republic of China (http://stats.customs.gov.cn/, accessed on 1 July 2024); Economics & Technology Research Institute, CNPC | |

| Stability test variable | Diplomacy_rank_energy | Joint statement involving energy or not | Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (https://www.gov.cn/, accessed on 1 July 2024); Author Compilation |

| Categorical variable | Neighbor | Whether the partner country is a neighboring country of China or not | |

| Belt and Road Plan | Whether the partner country is a “The Belt and Road” signatory country or not |

| Category | Base Models | Models with a One-Period Forward Shift | Models with a Two-Period Forward Shift | Substitution | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 | Model 6 | Model 7 | Model 8 | Model 9 | Model 10 | Mode 11 | Model 12 |

| leader_meet_num | 50.268 *** | 49.523 *** | 53.193 *** | 78.023 *** | ||||||||

| first_meet | −172.85 | −191.64 | −168.05 | −215.29 | ||||||||

| diplomacy_rank | 68.93 | 56.06 | 58.22 | 59.97 | ||||||||

| diplomacy_rank_oil | −154.043 *** | −157.688 *** | −149.632 *** | |||||||||

| diplomacy_rank_energy | −85.475 *** | |||||||||||

| meet_in_china | −93.517 *** | −98.354 *** | −91.698 *** | −90.730 *** | ||||||||

| two_side | 82.930 * | 78.265 * | 90.495 ** | 78.201 * | ||||||||

| Lleader_meet_num | 57.969 *** | 49.012 *** | 62.520 *** | 83.200 *** | ||||||||

| Lfirst_meet | −211.15 | −209.97 | −209.01 | −242.55 | ||||||||

| Ldiplomacy_rank | 75.11 | 59.94 | 62.38 | 63.08 | ||||||||

| Ldiplomacy_rank_oil | −118.466 ** | −113.839 *** | −107.539 ** | |||||||||

| Ldiplomacy_rank_energy | −70.568 *** | |||||||||||

| Lmeet_in_china | −83.775 *** | −84.738 *** | −84.603 *** | −80.831 *** | ||||||||

| Ltwo_side | 91.318 ** | 93.129 ** | 99.565 ** | 93.319 ** | ||||||||

| LLleader_meet_num | 45.013 *** | 35.650 ** | 49.994 *** | 44.599 ** | ||||||||

| LLfirst_meet | −184.07 | −201.32 | −186.90 | −213.92 | ||||||||

| LLdiplomacy_rank | 180.58 | 161.37 | 170.53 | 167.45 | ||||||||

| LLdiplomacy_rank_oil | −89.429 * | −89.261 ** | −78.624 * | |||||||||

| LLdiplomacy_rank_energy | −11.06 | |||||||||||

| LLmeet_in_china | −76.984 ** | −77.880 *** | −78.751 *** | −81.145 *** | ||||||||

| LLtwo_side | 121.200 *** | 126.729 *** | 127.470 *** | 115.292 ** | ||||||||

| Control | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Time Fixed | YES | YES | YES | |||||||||

| Nation Fixed | YES | YES | YES | |||||||||

| Time&Nation Fixed | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | ||||||

| Observations | 989.00 | 989.00 | 989.00 | 903.00 | 903.00 | 903.00 | 860.00 | 860.00 | 860.00 | 989.00 | 903.00 | 860.00 |

| Number of id | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 | 43.00 |

| R-squared | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.55 | 0.53 | 0.52 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.53 |

| Category | “Belt and Road” Countries | Non-“Belt and Road” Countries | Neighboring Countries | Non-Neighboring Countries | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | Model 13 | Model 14 | Model 15 | Model 16 | Model 17 | Model 18 | Model 19 | Model 20 | Model 21 | Model 22 | Model 23 | Model 24 |

| leader_meet_num | 78.138 *** | 24.816 | 318.492 *** | −25.411 * | ||||||||

| first_meet | −425.808 | 43.008 | −255.713 | −161.103 | ||||||||

| diplomacy_rank | 92.968 | 25.983 | 38.337 | 24.534 | ||||||||

| diplomacy_rank_oil | −130.887 * | −39.055 | −367.105 * | 33.574 | ||||||||

| meet_in_china | −183.772 *** | −12.99 | −263.671 ** | 20.587 | ||||||||

| two_side | 149.042 * | −11.961 | 385.405 ** | 27.937 | ||||||||

| Lleader_meet_num | 88.180 *** | 41.131 ** | 318.144 *** | −12.007 | ||||||||

| Lfirst_meet | −492.603 | 11.442 | −145.58 | −207.715 | ||||||||

| Ldiplomacy_rank | 100.072 | −66.549 | 201.549 | −53.49 | ||||||||

| Ldiplomacy_rank_oil | −115.38 | −42.594 | −337.144 | 50.533 | ||||||||

| Lmeet_in_china | −158.194 *** | −6.004 | −211.247 * | 11.05 | ||||||||

| Ltwo_side | 197.763 ** | −10.123 | 354.798 * | 45.169 | ||||||||

| LLleader_meet_num | 89.323 *** | 38.265 * | 331.090 *** | −11.351 | ||||||||

| LLfirst_meet | −317.004 | −196.824 | −89.422 | −212.244 | ||||||||

| LLdiplomacy_rank | 86.57 | 51.078 | 168.88 | 111.098 | ||||||||

| LLdiplomacy_rank_oil | −114.809 | −27.978 | −375.542 | 82.332 * | ||||||||

| LLmeet_in_china | −165.335 *** | −23.506 | −200.289 | −9.174 | ||||||||

| LLtwo_side | 313.643 *** | −15.488 | 417.538 ** | 14.447 | ||||||||

| Control | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Constant | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| TimeFixed*Nation Fixed | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 374 | 357 | 340 | 572 | 546 | 520 | 88 | 84 | 80 | 858 | 819 | 780 |

| Number of id | 17 | 17 | 17 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| R-squared | 0.66 | 0.64 | 0.63 | 0.46 | 0.47 | 0.48 | 0.70 | 0.64 | 0.59 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.63 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Li, B.; Ren, Z.; Gao, P. A Study on the Impact of Energy Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade. Energies 2025, 18, 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040851

Li B, Ren Z, Gao P. A Study on the Impact of Energy Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade. Energies. 2025; 18(4):851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040851

Chicago/Turabian StyleLi, Boyuan, Zhongyuan Ren, and Ping Gao. 2025. "A Study on the Impact of Energy Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade" Energies 18, no. 4: 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040851

APA StyleLi, B., Ren, Z., & Gao, P. (2025). A Study on the Impact of Energy Diplomacy on China’s Crude Oil Trade. Energies, 18(4), 851. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18040851