Issues Related to Water Hammer in Francis-Turbine Hydropower Schemes: A Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Water Hammer Phenomena in Hydropower Plants

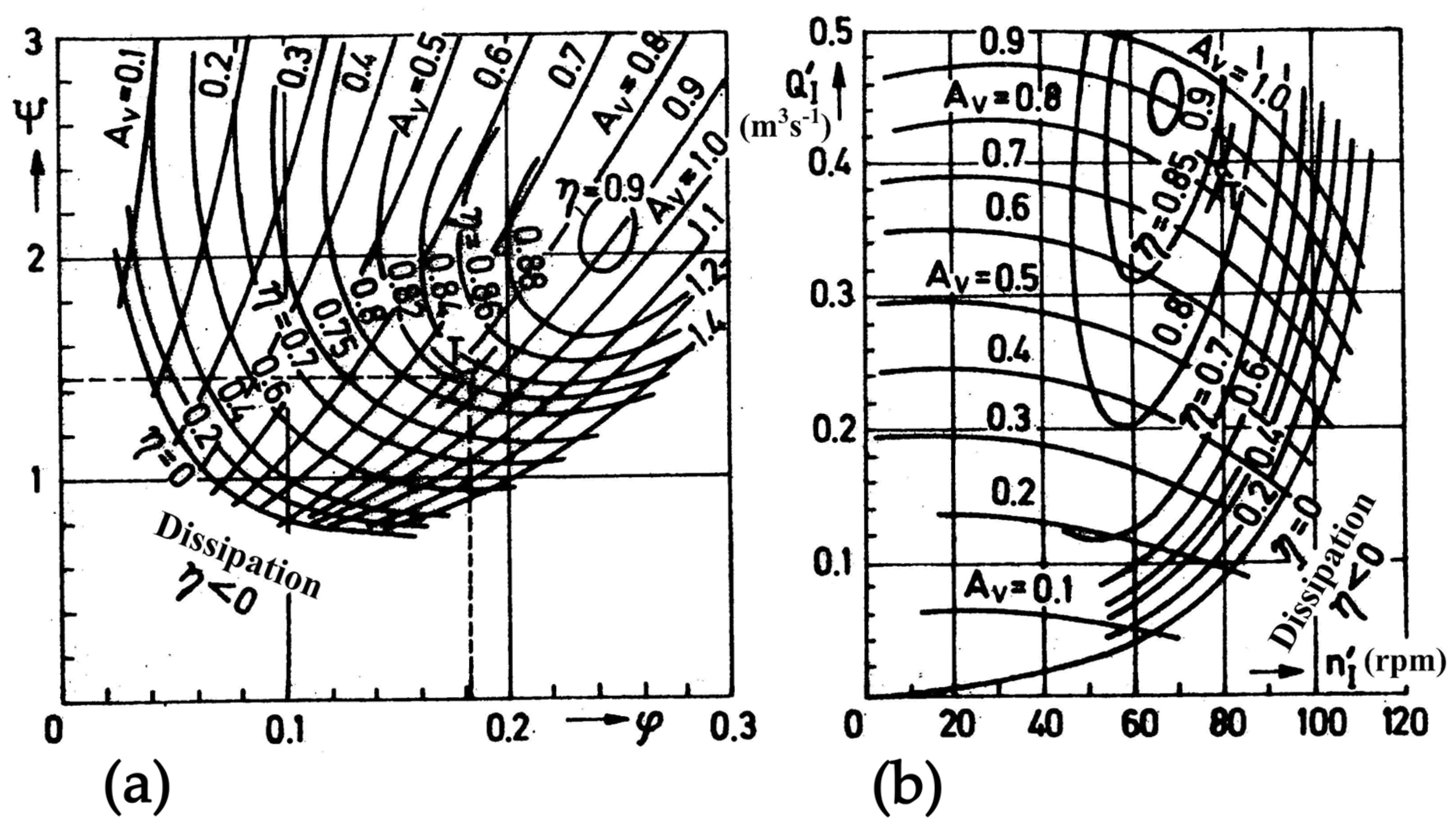

2.1. Note on Hydraulic Turbines

2.2. Critical Operating Modes

- (i)

- Normal operating regimes

- (ii)

- Safety operating modes

- (iii)

- Exceptional operating modes

3. Safety and Mitigation Measures

- (i)

- Ensure the highest possible level of safety of the hydroelectric power plant for all intended operating modes;

- (ii)

- Determine and observe appropriate limit values for specific operating parameters;

- (iii)

- Identify the most unfavorable operating modes and ensure that the limit values of the operating parameters are not exceeded.

- (i)

- Alteration of operational regimes;

- (ii)

- Installation of water hammer control devices in hydropower flow-passage system;

- (iii)

- Redesign of hydropower plant waterway system;

- (iv)

- Limitation of operating conditions.

3.1. Alteration of Operating Regimes

3.2. Installation of Water Hammer Control Devices in the Hydropower Plant Flow-Passage System

- (i)

- Increased Francis-turbine unit inertia (adding flywheel to small units, increasing the generator inertia);

- (ii)

- Resistors (to absorb excessive power);

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Pressure-regulating valve (operates synchronously with the turbine guide vane mechanism) [30];

- (v)

- Pressure-relief valve (opens at a set pressure, for small units);

- (vi)

- Rupture disk (bursts at a set pressure, for small units);

- (vii)

- Aeration pipe (attenuates unwanted transient air-water flow effects) or air valve (attenuates water column separation effects, removes trapped air) [31]; both release unwanted air from the water-conveyance system (tunnel, penstock).

3.3. Redesign of Hydropower Plant Flow-Passage System

- (i)

- Change in the tunnel or penstock profile (high point), dimensions (diameter, pipe-wall thickness, length) and material (steel and plastic) [32];

- (ii)

- Re-arrangement of the placement of the surge protective elements along the waterway system (valve, surge tank, air valve).

3.4. Limitation of Operating Conditions

- (i)

- Limiting maximum operating discharge;

- (ii)

- Limiting maximum and minimum gross heads;

- (iii)

- Limiting maximum and minimum unit power.

4. Modern Approach to Treatment

- (i)

- Civil engineering (hydrology, hydraulics, and hydraulic structures);

- (ii)

- Mechanical engineering (fluid mechanics, hydraulic turbines, hydromechanical and auxiliary equipment, turbine governor);

- (iii)

- Electrical engineering (generators, electrical power control, and electrical distribution systems).

5. Water Hammer Modeling

5.1. Elastic Water Column Model

5.2. Rigid Water Hammer Model

5.3. Methods of Solution for Water Hammer Equations

5.3.1. Analytical Methods

5.3.2. Numerical Methods

- (i)

- (ii)

- (iii)

- (iv)

- Wave characteristic method (WCM) [74];

- (v)

- (v-i)

- (v-ii)

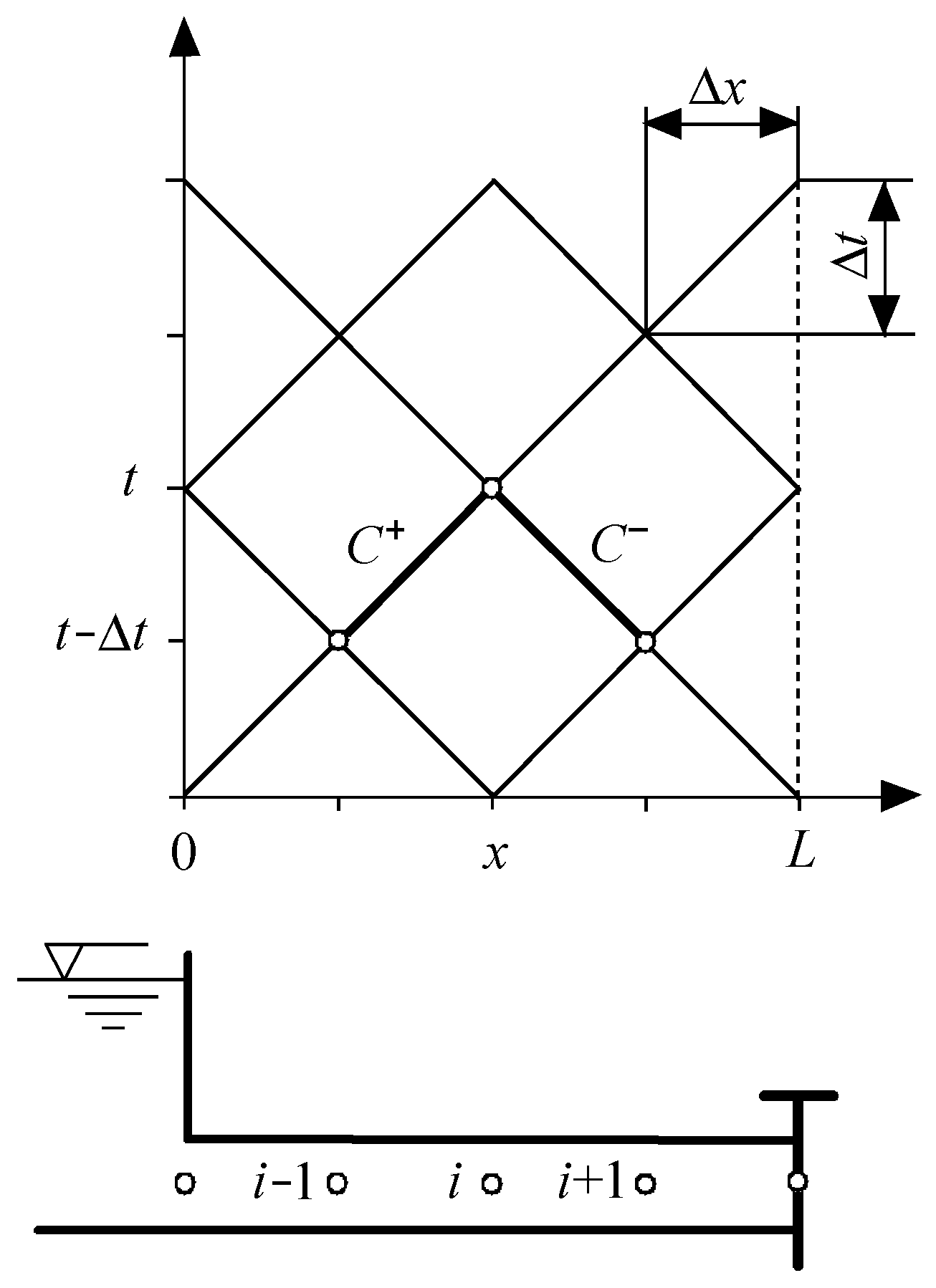

Method of Characteristics

- -

- Along the C+ characteristic line (Δx/Δt = a),

- -

- Along the C− characteristic line (Δx/Δt = −a),

- -

- Water hammer compatibility Equations (9) and (10)

- -

- Head balance equation:

- -

- Dynamic equation of the turbine unit rotating masses:

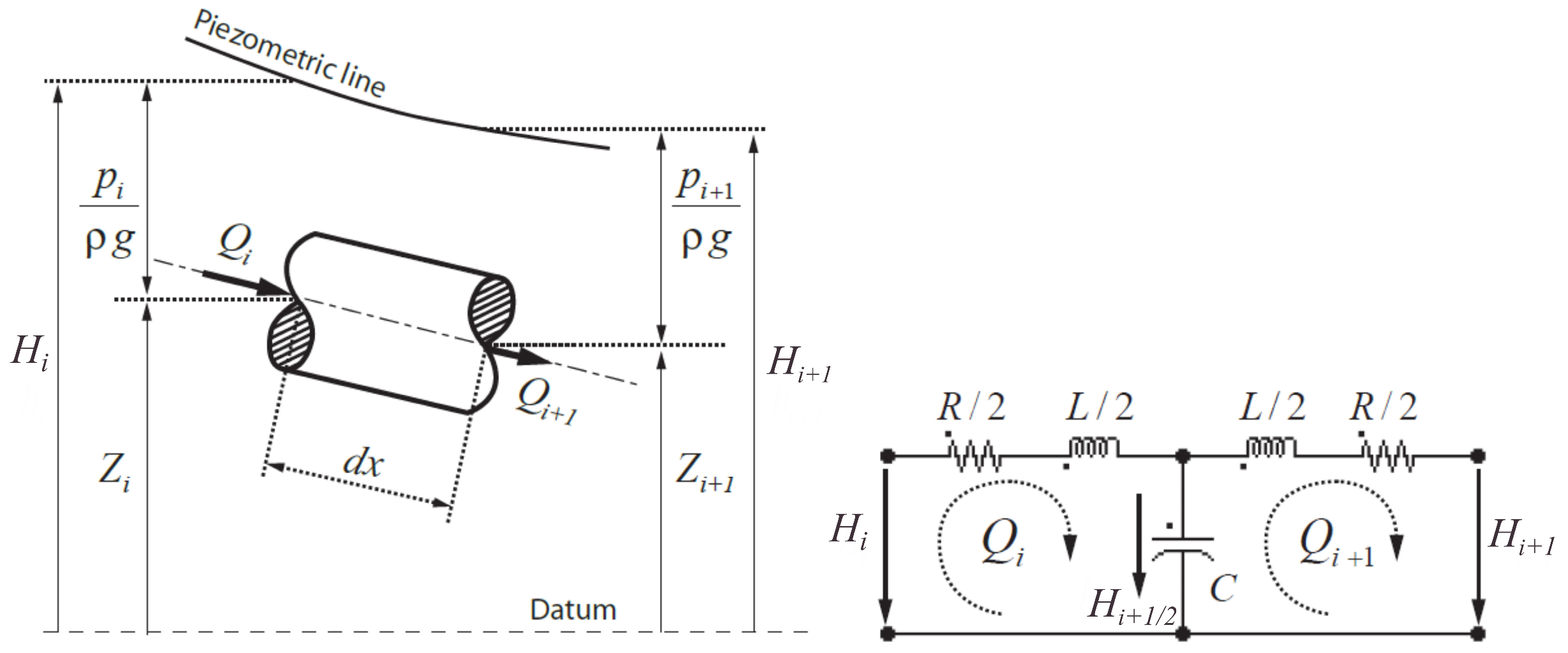

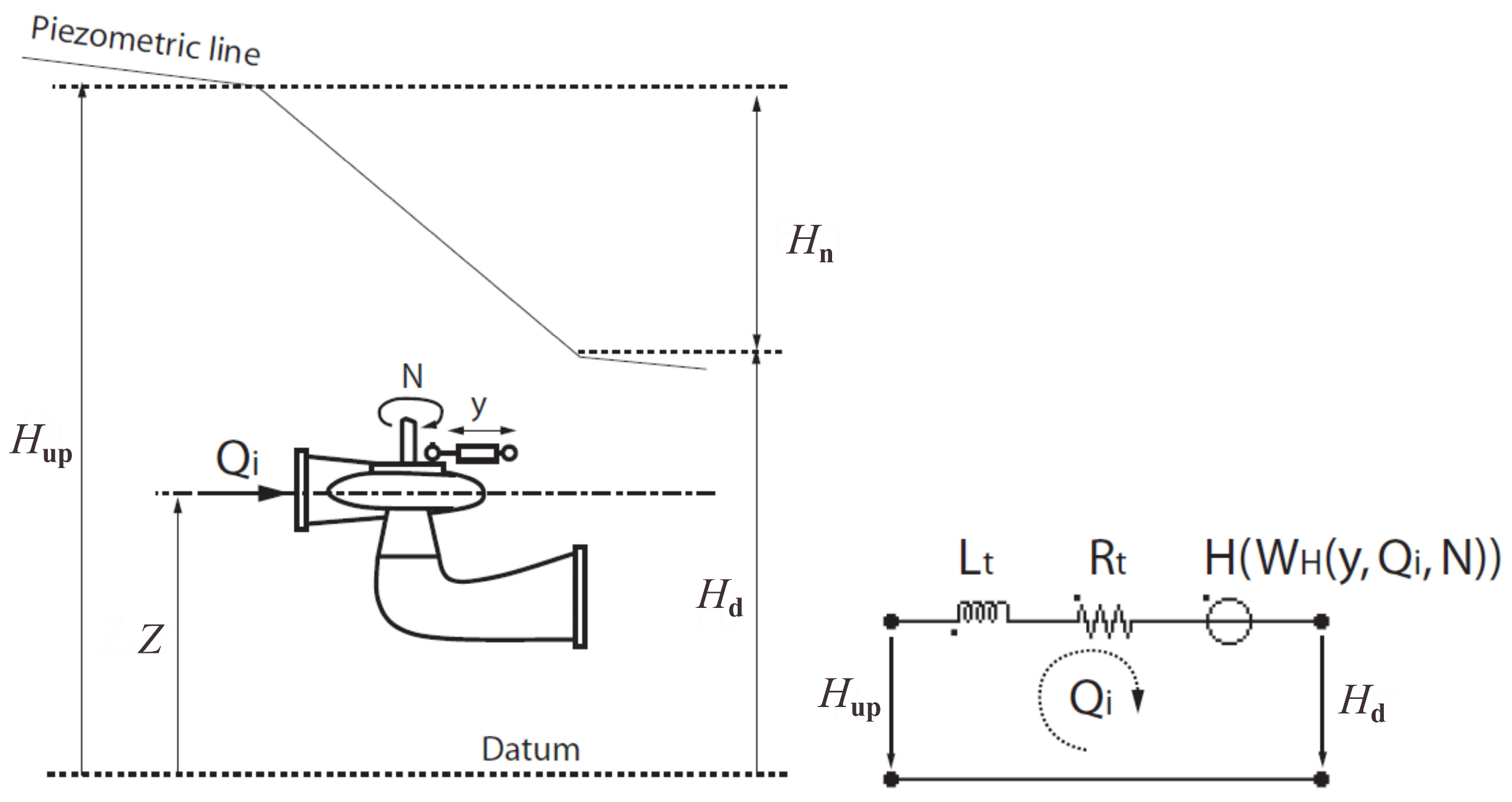

Electrical-Analogy-Based Finite Difference Method

5.4. Note on Multidimensional Water Hammer Modeling

6. Validation and Discussion of 1D Water Hammer Models Applied to Hydropower Systems

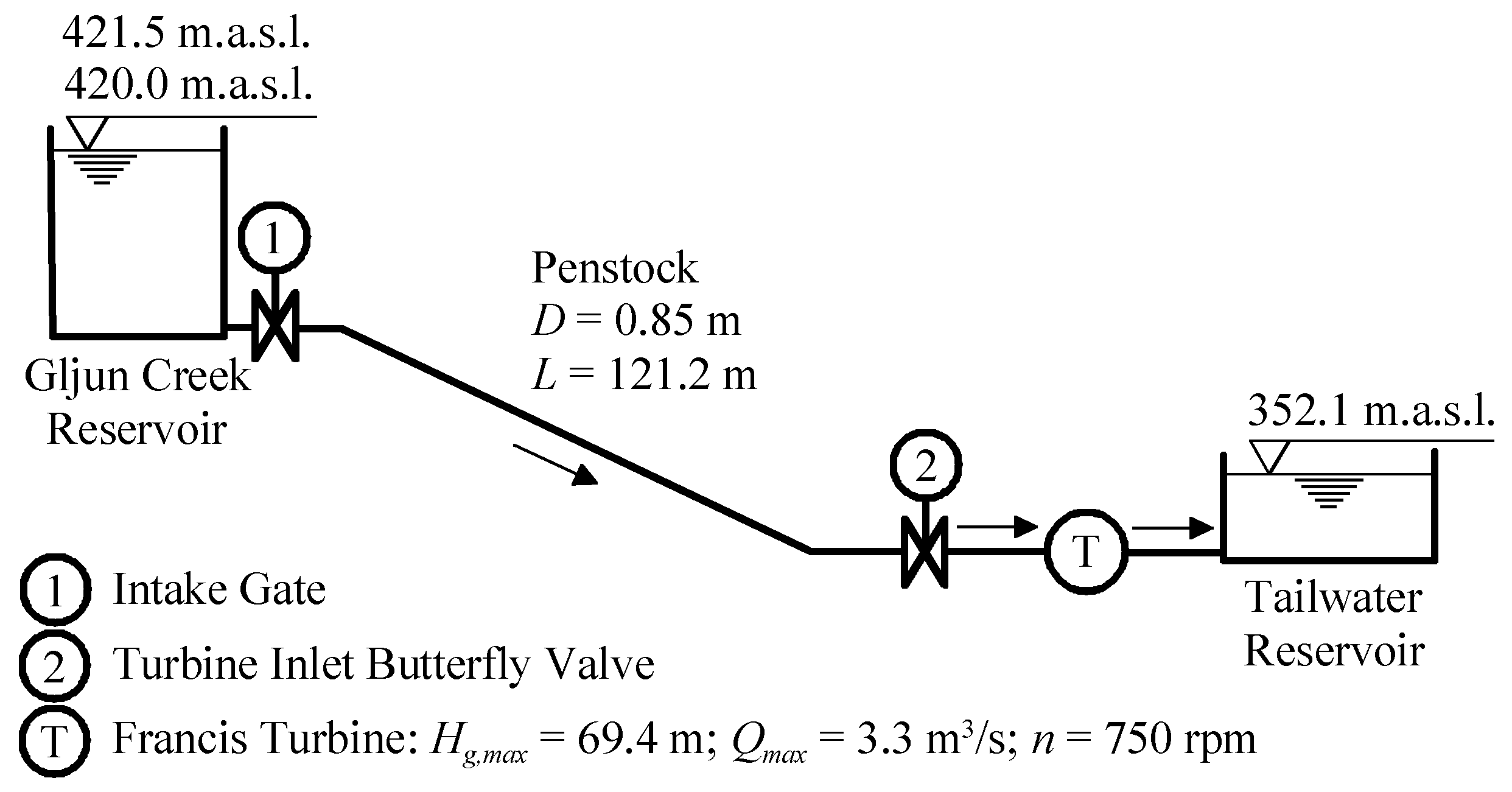

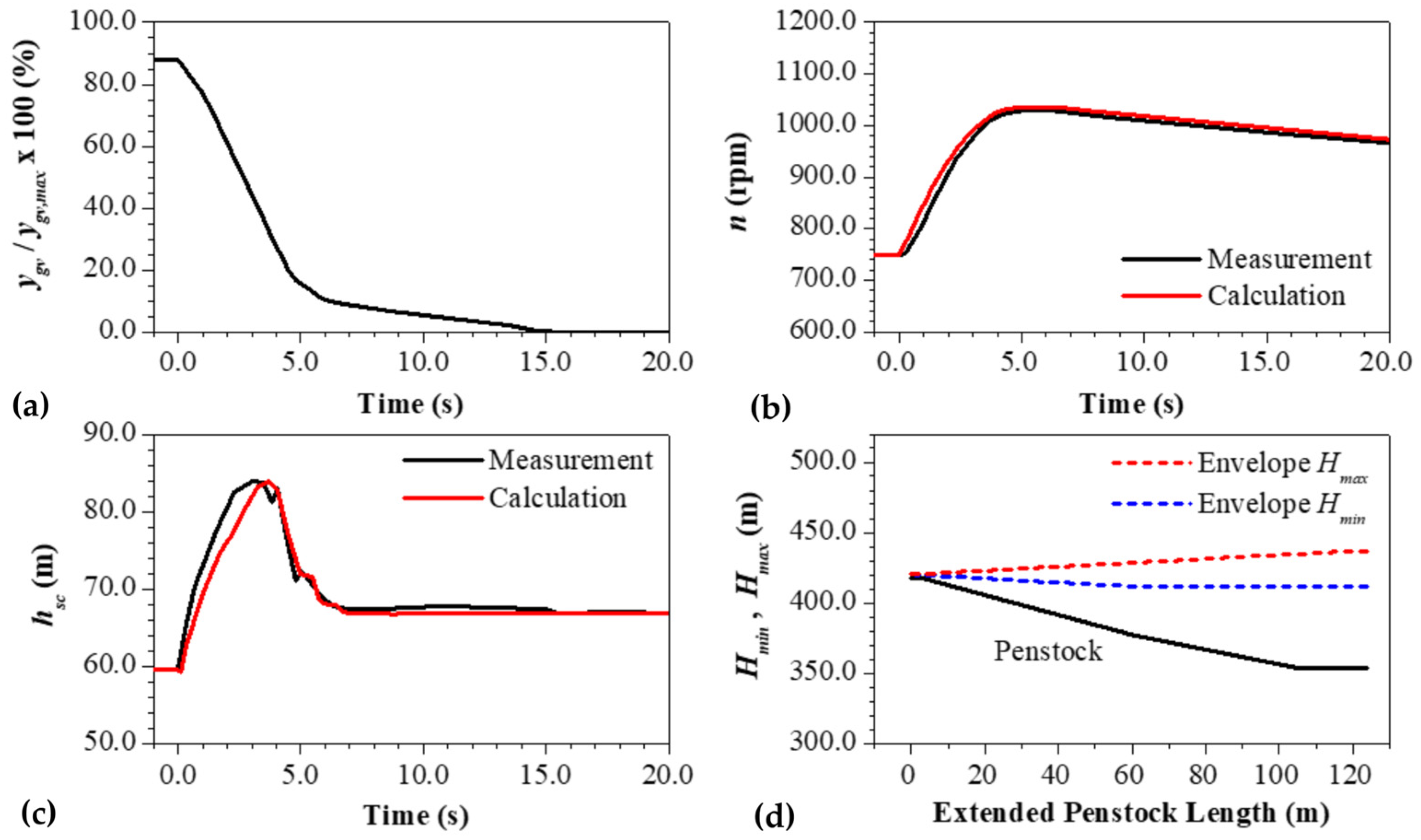

6.1. Plužna Small Hydropower Plant

Emergency Shutdown of the Turbine from Full Load

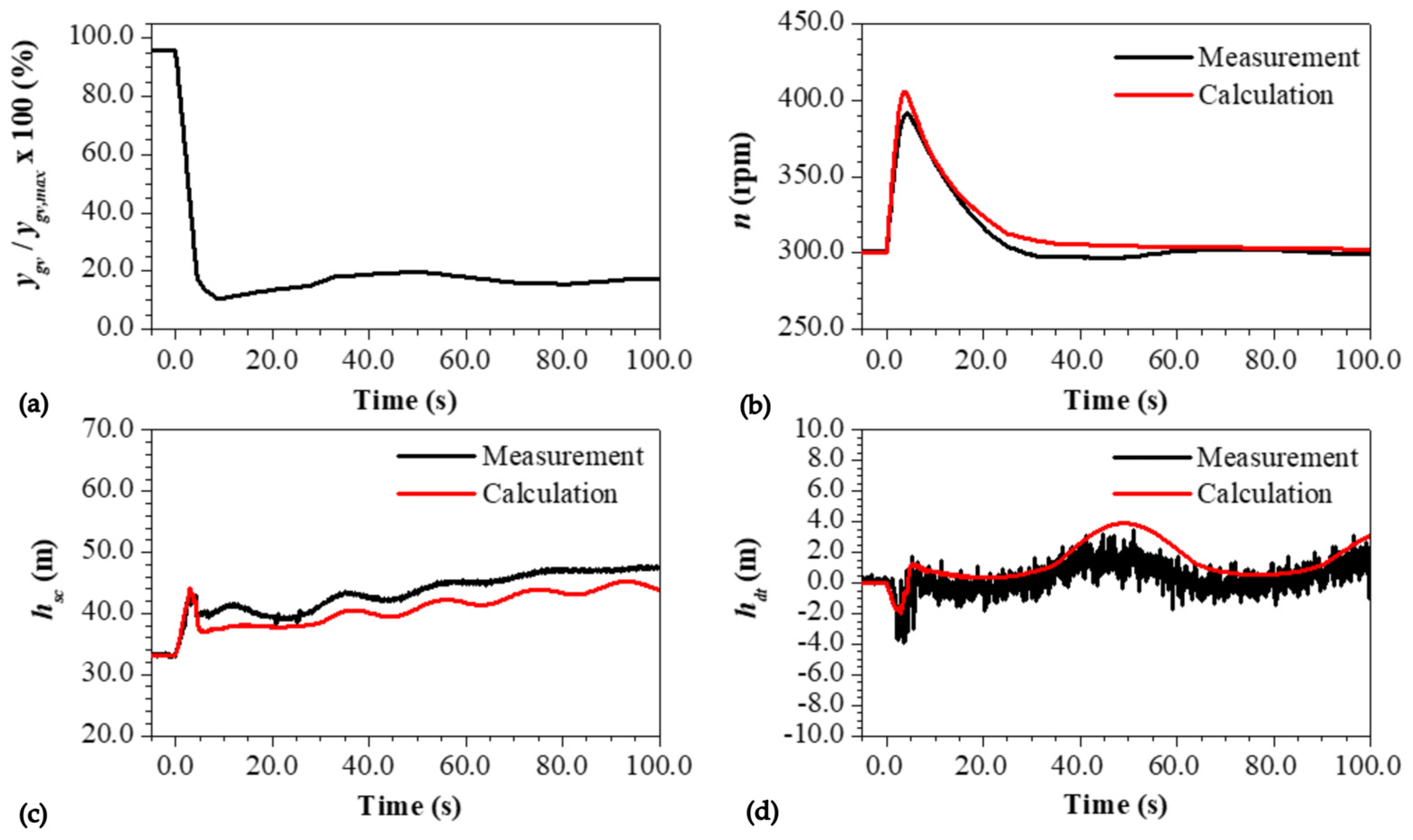

6.2. Toro II Hydropower Plant

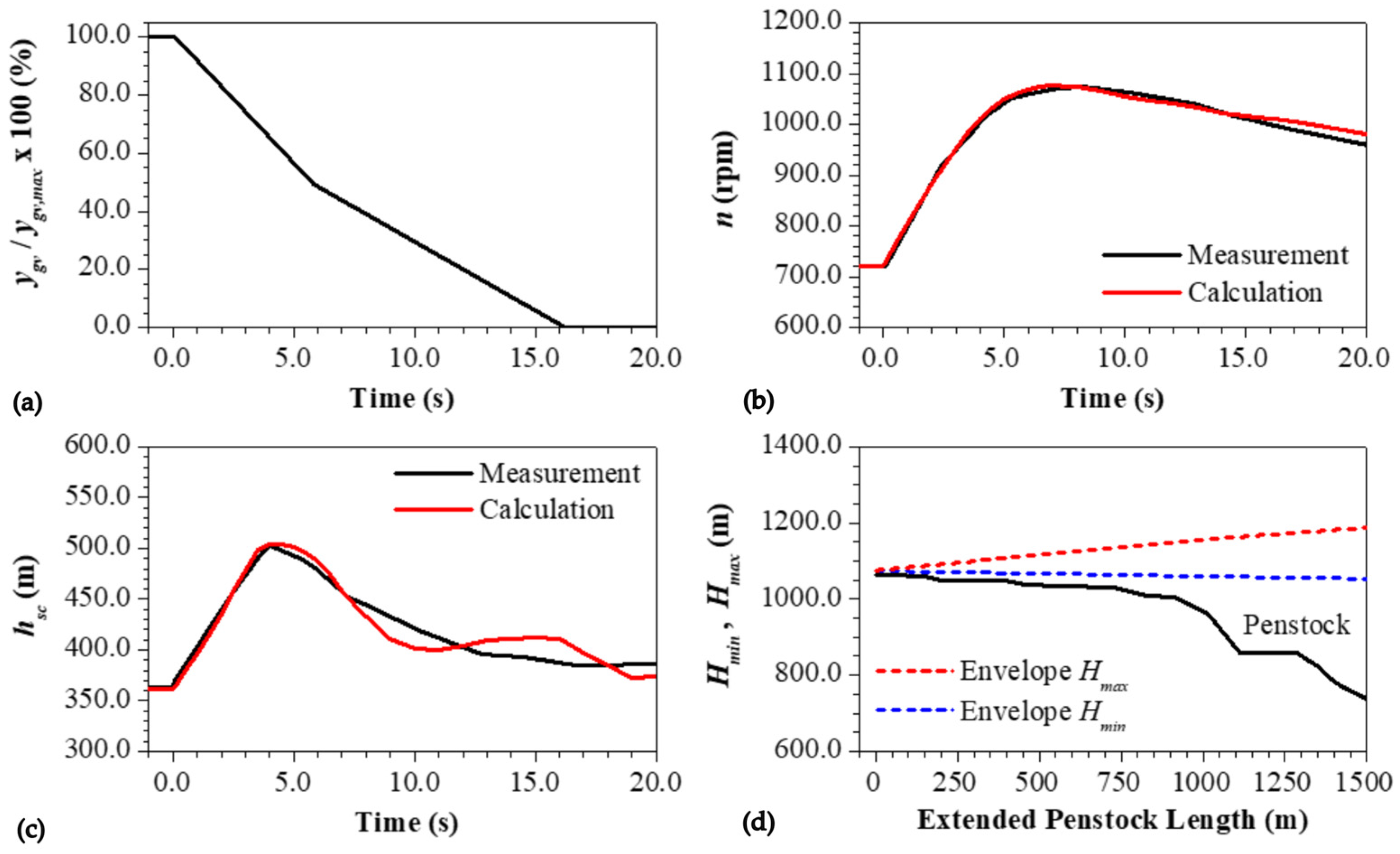

Simultaneous Emergency Shutdown of Two Turbine Units from Full Load

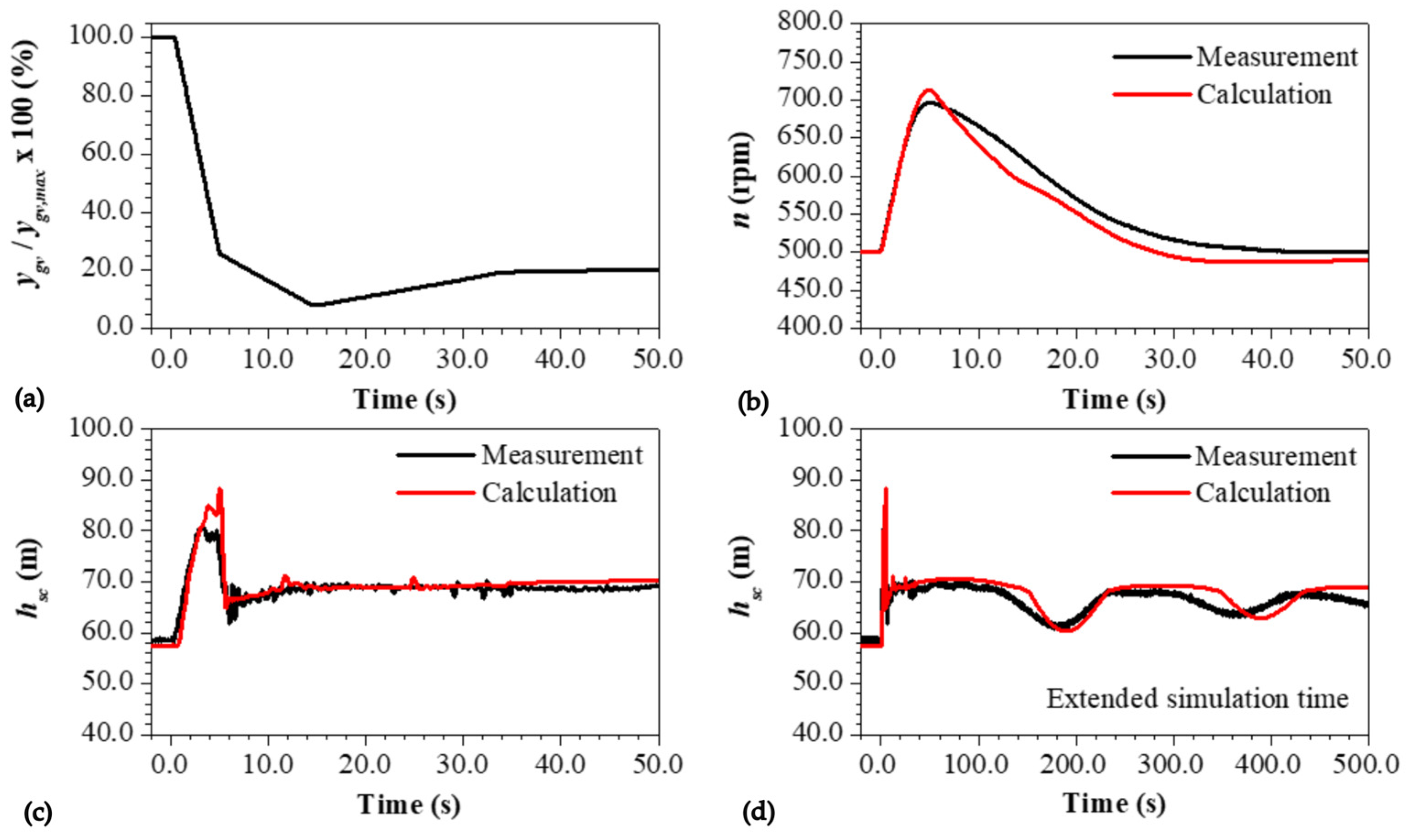

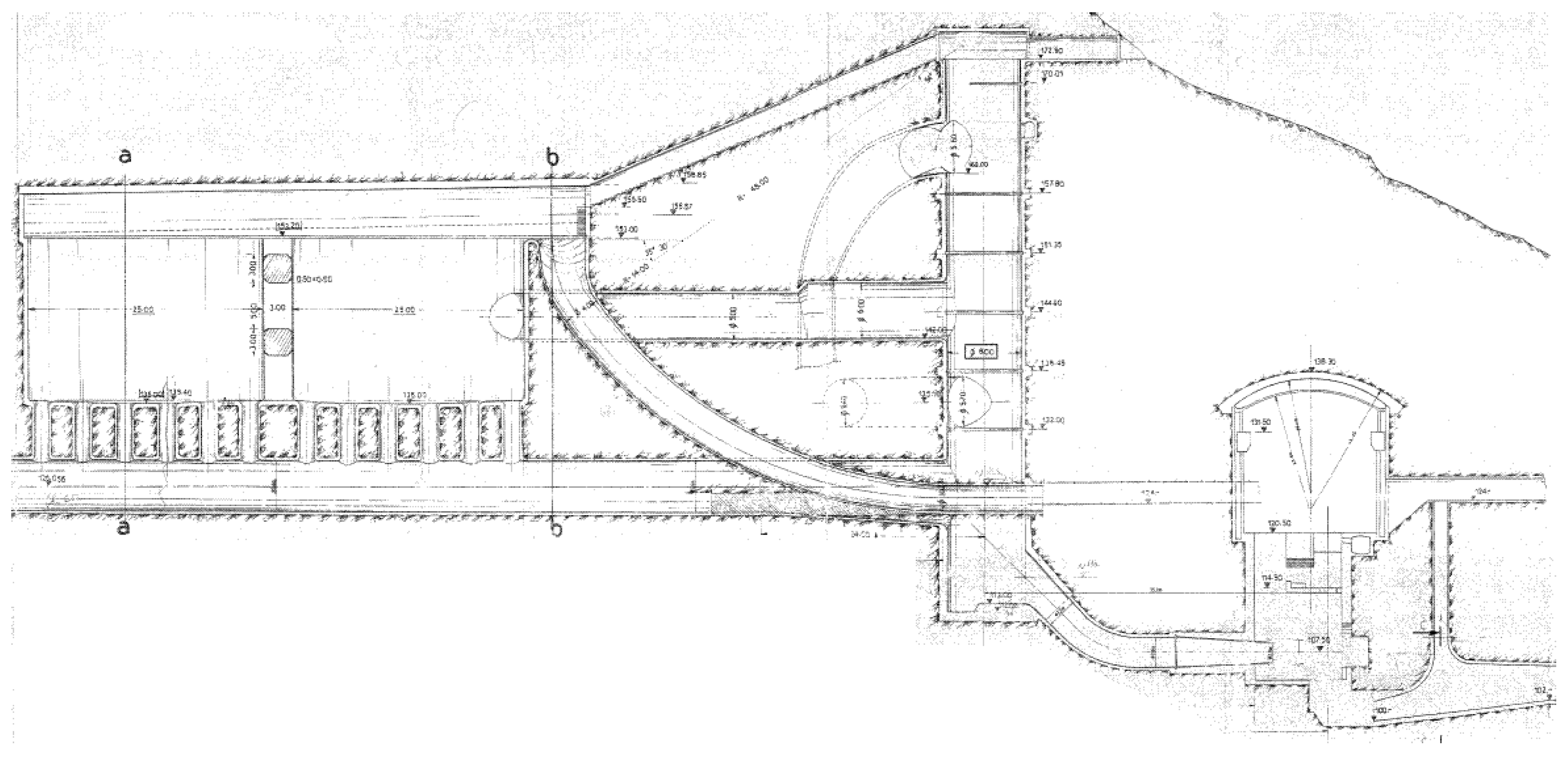

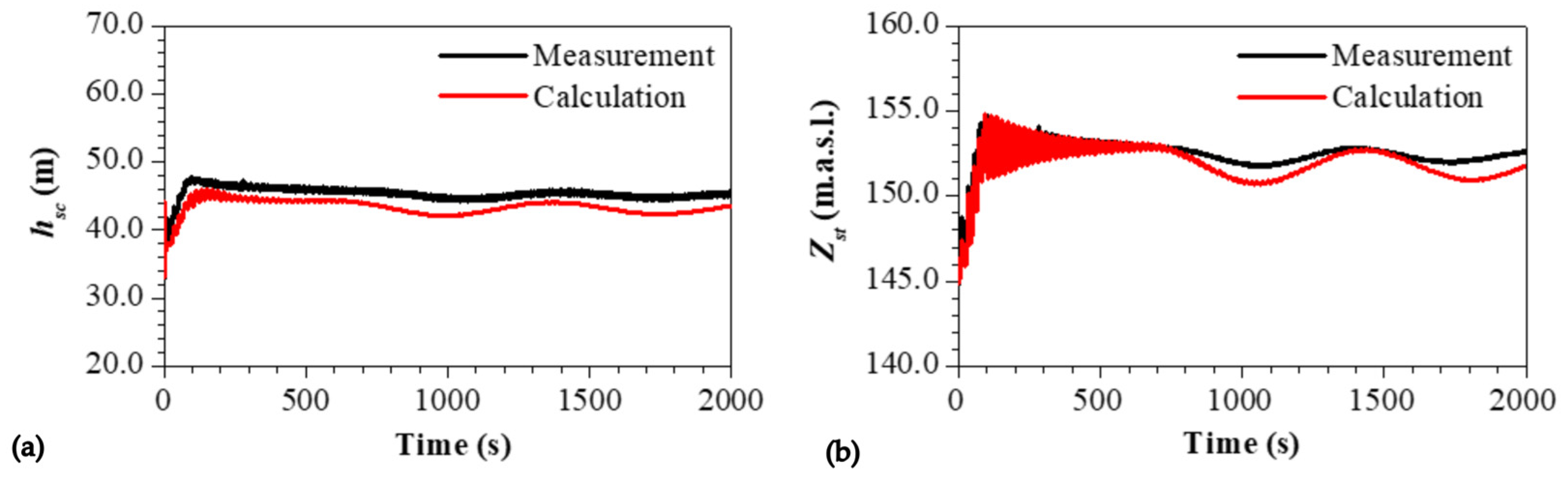

6.3. Moste Hydropower Plant

Simultaneous Full-Load Rejection of Two Turbines

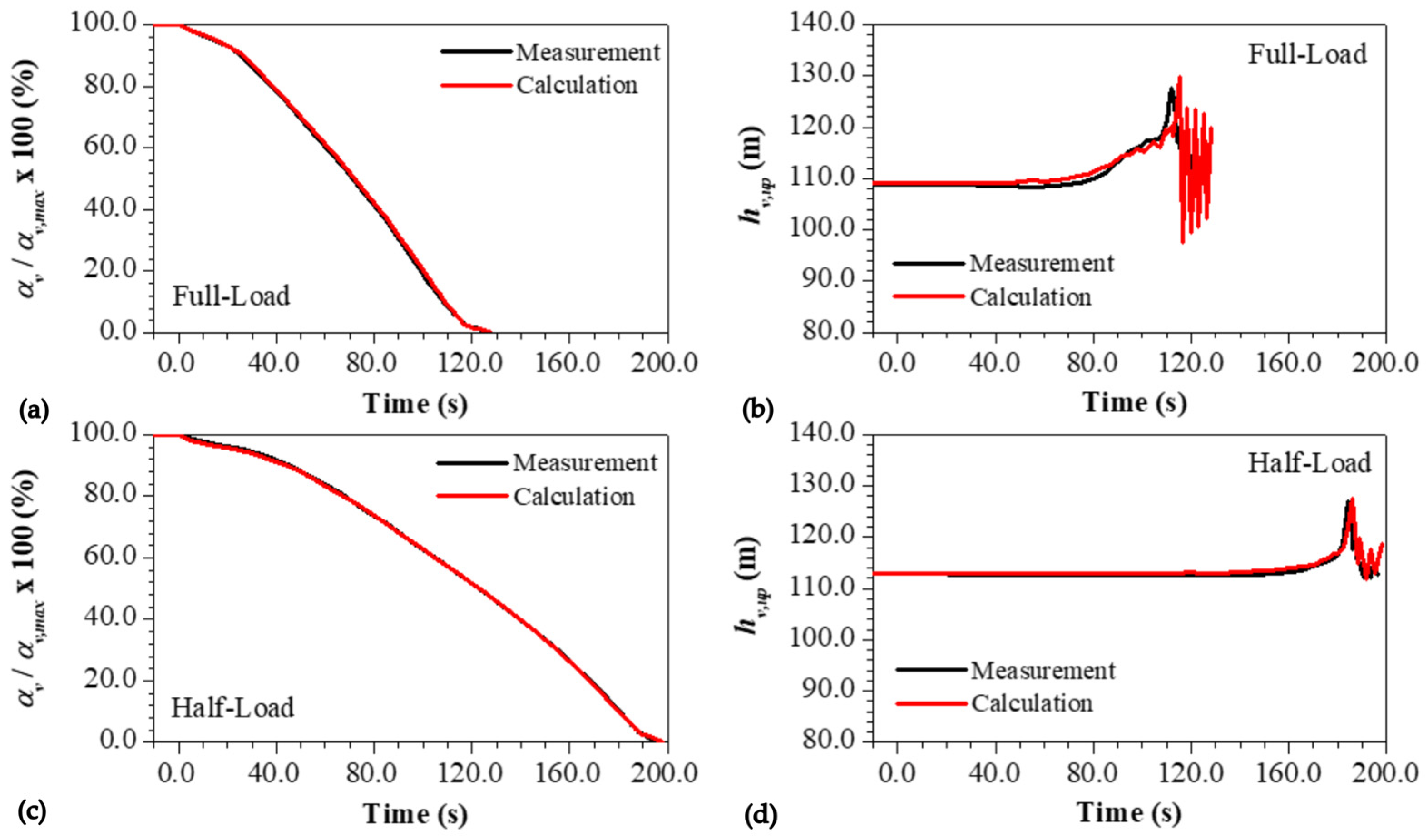

6.4. Doblar I Hydropower Plant

Simultaneous Load Rejection of Three Turbine Units

6.5. Lomščica Small Hydropower Plant

6.6. Computational Error Analysis

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| A | cross-sectional area (m2) |

| Av | dimensionless guide vane opening (-) |

| a | pressure wave speed (m·s−1) |

| C | hydraulic capacitance (m2) |

| C′ | lineic hydraulic capacitance (m) |

| D | conduit internal diameter (m) |

| D1 | runner inlet diameter (m) |

| D2 | runner outlet diameter (m) |

| f | Darcy–Weisbach friction factor (-) |

| g | acceleration due to gravity (m·s−2) |

| H | piezometric head (m) |

| Hd | downstream piezometric head (m) |

| Hg | gross head (m) |

| Hn | net head (m) |

| Hr | rated net head (m) |

| Hup | upstream piezometric head (m) |

| h | pressure head (m) |

| Δh | pressure head rise (m) |

| I | polar moment of inertia (kg·m2) |

| i | electrical current (A) |

| L | pipe length (m), hydraulic inductance (s2·m−2) |

| L′ | lineic hydraulic inductance (s2·m−3) |

| n | rotational speed (rpm; rps) |

| nr | rated runner rotational speed (rpm) |

| nq | turbine specific speed (rpm) |

| unit rotational speed (rpm) | |

| P | power (W) |

| P0 | initial power (W) |

| p | pressure (Pa) |

| discharge (m3·s−1) | |

| downstream discharge (m3·s−1) | |

| upstream discharge (m3·s−1) | |

| rated turbine discharge (m3·s−1) | |

| turbine unit discharge (m3·s−1) | |

| R | hydraulic resistance (s·m−2) |

| R′ | lineic hydraulic resistance (s·m−3) |

| T | turbine runner torque (N·m) |

| Tr | rated turbine runner torque (N·m) |

| Tm | mechanical starting time (s) |

| Tw | water starting time (s) |

| t | time (s) |

| tc | closing time (s) |

| tr | pipe reflection time tr = 2L/a (s) |

| U | electrical voltage (V) |

| v | uniform axial flow velocity (m·s−1) |

| v0 | initial uniform axial flow velocity (m·s−1) |

| WH | dimensionless head characteristics (-) |

| WT | dimensionless torque characteristics (-) |

| x | axial coordinate (m) |

| y | dimensionless servomotor stroke (-) |

| Z | elevation (m.a.s.l.) |

| valve opening angle (deg) | |

| Δh | pressure head rise (m) |

| Δn | rotational speed rise (%) |

| Δt | time-step (s) |

| Δx | computational reach length (m) |

| η | efficiency (-) |

| θ | pipe inclination (rad) |

| φ | dimensionless discharge number (-) |

| dimensionless pressure head number (-) | |

| angular frequency (rad·s−1) | |

| Subscripts | |

| 0 | initial |

| all | permissible |

| c | computed, closure |

| d | downstream |

| dt | draft tube |

| Err | error |

| e | equivalent |

| g | gross |

| gen | generator |

| gv | guide vane |

| spatial index | |

| measured | |

| max | maximum |

| min | minimum |

| r | rated, reflection |

| sc | scroll case |

| st | surge tank |

| up | upstream |

| v | valve |

| Abbreviations | |

| 1D, 3D | one-, three-dimensional |

| FDM | finite difference method |

| FEM | finite element method |

| FVM | finite volume method |

| HPP | hydropower plant |

| MOC | method of characteristics |

| RLC | resistor, inductor and capacitor electrical circuit |

| SHPP | small hydropower plant |

| WCS | wave characteristic method |

| WRM | weighted residual method |

References

- Brown, S.; Jones, D. European Electricity Review 2024; Ember: London, UK, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Quaranta, E.; Bonjean, M.; Cuvato, D.; Nicolet, C.; Dreyer, M.; Gaspoz, A.; Rey-Mermet, S.; Boulicaut, B.; Pratalata, L.; Pinelli, M.; et al. Hydropower case study collection: Innovative low head and ecologically improved turbines, hydropower in existing infrastructures, hydropeaking reduction, digitalization and governing systems. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, P. Flexible Operation of Hydropower Plants; Electrical Power Research Institute: Palo Alto, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Vagnoni, E.; Gezer, D.; Anagnostopoulos, I.; Cavazzini, G.; Doujak, E.; Hočevar, M.; Rudolf, P. The new role of sustainable hydropower in flexible energy systems and its technical evolution through innovation. Renew. Energy 2024, 230, 120832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quaranta, E.; Aggidis, G.; Boes, R.M.; Comoglio, C.; De Michele, C.; Patro, E.R.; Georgievskaia, E.; Harby, A.; Kougias, I.; Muntean, S.; et al. Assessing the energy potential of modernizing the European hydropower fleet. Energy Convers. Manag. 2021, 246, 114655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Đorđević, B. Korišćenje Vodnih Snaga. Objekti Hidroelektrana (Use of Water Power. Hydraulic Power Plant Facilities); Građevinski fakultet, Beograd and Naučna knjiga: Beograd, Serbia, 1984. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhry, M.H. Applied Hydraulic Transients; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Lupa, S.I.; Gagnon, M.; Muntean, S.; Abdul-Nour, G. The impact of water hammer on hydraulic power units. Energies 2022, 15, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ASME. The Guide to Hydropower Mechanical Design; HCI Publications: Kansas, MO, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Pejović, S.; Boldy, A.P.; Obradović, D. Guidelines to Hydraulic Transient Analysis; Gower Technical Press: Aldershot, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, X.D.; Zhang, J.; Chen, S.; Liu, J.C. Stability analysis of the governor-turbine-hydraulic system of pump storage plant during small load variation. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2016, 49, 112004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, B.; Zhang, J.; Egusquiza, M.; Chen, D.; Li, F.; Behrens, P.; Egusquiza, E. A review of dynamic models and stability analysis for a hydro-turbine governing system. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 144, 110880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lupa, S.I.; Gagnon, M.; Muntean, S.; Abdul-Nour, G. Investigation of water hammer in the hydraulic passage of hydropower plants equipped with Francis turbines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2022, 1079, 012003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raabe, J. Hydro Power. The Design, Use, and Function of Hydromechanical, Hydraulic, and Electrical Equipment; VDI Verlag: Düsseldorf, Germany, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Bortoni, E.; de Souza, Z.; Viana, A.; Villa-Nora, H.; Rezek, A.; Pinto, L.; Sinishalchi, R.; Braganca, R.; Bernardes, J., Jr. The benefits of variable speed operation in hydropower plants driven by Francis turbines. Energies 2019, 12, 3719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benišek, M. Hidrauličke Turbine (Hydraulic Turbines); Mašinski fakultet: Beograd, Serbia, 1998. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Krivchenko, G.I.; Arshenevskii, N.N.; Kvjatkovskaja, E.V.; Klabukov, V.M. Gidromehanicheskie Perehodnie Processi v Gidroenergeticheskih Ustanovkah (Hydromechanical Transient Regimes in Hydroelectric Power Plants); Energiya: Moscow, Russia, 1975. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- IEC 60193:2019; Hydraulic Turbines, Storage Pumps and Pump-Turbines—Model Acceptance Tests. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2019.

- Jordan, V. Prehodni Režimi v Hidravličnih Cevnih Sistemih (Transient Regimes in Hydraulic Piping Systems); Partizanska knjiga: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 1983. (In Slovene) [Google Scholar]

- Wylie, E.B.; Streeter, V.L. Fluid Transients in Systems; Prentice-Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Karney, B.; Pejović, S.; Mazij, J. Treatise on water hammer in hydropower standards and guidelines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2014, 22, 042007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achitaev, A.; Ilyushin, P.; Suslov, K.; Kobyletski, S. Dynamic simulation of starting and emergency conditions of a hydraulic unit based on a Francis turbine. Energies 2022, 15, 8044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilić, J.; Petković, A.; Božić, I. Numerical analysis of water hammer and water-mass oscillations in a hydropower plant for the most extreme operational regimes. FME Trans. 2019, 47, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trivedi, C.; Cervantes, M.J.; Gandhi, B.K. Investigation of high head Francis turbine at runaway operating conditions. Energies 2016, 9, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rakčević, S. Vzporedni izpust kot nadomestilo za zgornje vodostane pri hidroelektrarnah s francisovimi turbinami (By-pass valve as substitute for upstream surge tanks for hydropower plants with Francis turbines). Acta Hydrotech. 1984, 2, 1–57. (In Slovene) [Google Scholar]

- Lupa, S.I.; Muntean, S.; Abdul-Nour, G. Temporal interactions of water hammer factors during the load rejection regimes in a hydropower plant equipped with Francis turbines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2025, 1483, 012014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Liu, Y.; Qu, F.; Xu, X. A review of critical stable sectional areas for the surge tanks of hydropower stations. Energies 2020, 13, 6466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, J.; Zhai, X.; Hu, X.; Meng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Yang, G. Water hammer protection characteristics and hydraulic performance of a novel air chamber with adjustable central standpipe in a pressurized water supply system. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, T.; Chen, S.; Zhang, J.; Yu, X.; Lyu, J.; Yan, H. Comparison of hydraulic characteristics of vertical and horizontal air-cushion surge chambers in the hydropower station under load disturbances. Energies 2023, 16, 1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunca, G.; Bucur, D.M.; Bălăunţascu, I.; Călinoiu, C. Experimental analysis of the by-pass valves characteristics of Francis turbines. U.P.B. Sci. Bull. Ser. D 2013, 75, 215–222. [Google Scholar]

- Fuertes-Miquel, V.S.; López-Jiménez, P.A.; Martínez-Solano, F.J. Numerical modelling of pipelines with air pockets and air valves. Can. J. Civ. Eng. 2016, 43, 1052–1061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandil, M.; Kamal, A.M.; Sayed, T.A. Effect of pipe materials on water hammer. Int. J. Press. Vessel. Pip. 2020, 179, 103996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahraman, G. Investigation of the effect of operating conditions change on water hammer. J. Fail. Anal. Prev. 2020, 20, 1987–1991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliev, V.; Ivljanin, B.; Markov, Z.; Popovski, P. Sensitivity of transient phenomena analysis of the Francis turbine power plants. Int. J. Eng. Res. Appl. 2015, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, W.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, J.; Lai, X.; Liu, C.; Yang, J. A transient analysis framework for hydropower generating systems under parameter uncertainty by integrating physics-based and data-driven models. Energy 2024, 297, 131141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEC 60545:1976; Guide for Commissioning, Operation and Maintenance of Hydraulic Turbines. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1976.

- IEC 60805:1985; Guide for Commissioning, Operation and Maintenance of Storage Pumps and of Pump-Turbines Operating as Pumps. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1985.

- IEC 60041:1991; Field Acceptance Tests to Determine the Hydraulic Performance of Hydraulic Turbines, Storage Pumps and Pump-Turbines. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1991.

- IEC 60308:2005; Hydraulic Turbines—Testing of Control Systems. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2005.

- IEC 61362:1998; Guide for Specification of Hydraulic Control Systems. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998.

- IEC 62006:2010; Hydraulic Machines—Acceptance Tests of Small Hydroelectric Installations. IEC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Zobeiri, A.; Nicolet, C.; Vuandes, E. Risk Analysis of the Transient Phenomena in a Hydropower Plant Installation. In Proceedings of the Hydro 2011, Prague, Czech Republic, 17–19 October 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, C.; Gandhi, B.; Cervantes, M.J. Effects of transients on Francis turbine runner life: A review. J. Hydraul. Res. 2013, 51, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, B.; Arzaghi, E.; Abbassi, R.; Chen, D.; Aggidis, G.A.; Zhang, J.; Patelli, E. Transient safety assessment and risk mitigation of a hydroelectric generation system. Energy 2020, 196, 117135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savin, D.; Badina, C.; Pollier, R.; Drommi, J.L.; Baroth, J.; Chrobonnier, S.; Berenguer, C. Effect of start and stop cycles on hydropower plants: Modelling the deterioration of the equipment to evaluate the cycling cost. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2023, 1136, 012057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z. A review on damage mechanism in hydro turbines. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 54, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibault, D.; Trudel, A. The IEC 63230: A new standard on the fatigue of hydraulic turbines to help the industry face the energy transition. In Proceedings of the Hydro 2023, Edinburgh, UK, 16–18 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Presas, A.; Luo, Y.; Wang, Z.; Guo, B. Fatigue life estimation of Francis turbines based on experimental strain measurements: Review of the actual data and future models. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 102, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gummer, J.H.; Etter, S. Cracking of Francis runners during transient operation. Intl. J. Hydropower Dams 2008, 15, 81–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cassano, S.; Sossa, F. Stress-informed control of medium- and high-head hydropower plants to reduce penstock fatigue. Sustain. Energy Grids Net. 2022, 31, 100688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joukowsky, N. Über den Hydraulischen Stoss in Wasserleitungsröhren (About hydraulic hammer in water pipelines). Mem. Acad. Imp. Sci. St. Petersbourg 1900, 9, 1–71. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Karadžić, U. Developments in Valve-Induced Water-Hammer Experimentation in a Small-Scale Pipeline Apparatus. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Pressure Surges, Dublin, Ireland, 18–20 November 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Van’t Westende, J.M.C.; Koppel, T.; Gale, J.; Hou, Q.; Pandula, Z.; Tijsseling, A.S. Water Hammer and Column Separation Due to Accidental Simultaneous Closure of Control Valves in a Large-Scale Two-Phase Flow Experimental Test Rig. In Proceedings of the ASME Pressure Vessels and Piping Division/K-PVP Conference, Bellevue, WA, USA, 18–22 July 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghidaoui, M.; Zhao, M.; McInnis, D.A.; Axworthy, D.H. A review of water hammer theory and practice. Appl. Mech. Rev. 2005, 58, 49–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plouraboué, F. Review on water-hammer waves mechanical and theoretical foundations. Eur. J. Mech. B Fluids 2024, 108, 237–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karney, B.W. Energy relations in transient closed-conduit flow. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1990, 116, 1180–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmakian, J. Waterhammer Analysis; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1955. [Google Scholar]

- Arnautović, D. Matematički modeli hidrauličkih sistema hidroelektrana (Mathematical models of hydraulic systems in hydropower plants). Proc. Electr. Eng. Inst. Nikola Tesla 2004, 14, 19–31. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, G.R. Water hammer analysis by the Laplace-Mellin transformation. Trans. ASME 1945, 67, 361–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbanowicz, K.; Jing, H.; Bergant, A.; Stosiak, M.; Lubecki, M. Progress in analytical modeling of water hammer. J. Fluids Eng. 2023, 145, 081203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, S.L.; Strowger, E.B. Resume of Theory of Water Hammer. In Proceedings of the ASME Symposium of Water Hammer, Chicago, IL, USA, 30 June 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Đorđević, B. Korišćenje Vodnih Snaga. Osnove Hidroenergetskog Korišćenja Voda (Use of Water Power. Basis of Hydroenergetical Exploation of Water); Građevinski fakultet: Beograd, Serbia, 1981. (In Serbian) [Google Scholar]

- Warnick, C.C. Hydropower Engineering; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Pepa, D.; Ursoniu, C.; Gillich, R.N.; Campian, C.V. Water hammer effect in the spiral case and penstock of Francis turbines. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2017, 163, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nepal, T.; Bista, D.; Øyvang, T.; Sharna, R. Models for Hydropower Plant: A Review. In Proceedings of the SIMS 64, Västerås, Sweden, 26–27 September 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Wang, C.; Zeng, W. Transient simulations in hydropower based on a novel turbine boundary. Math. Probl. Eng. 2016, 2016, 1504659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyestanaki, M.K.; Dunca, G.; Jonsson, P.; Cervantes, M.J. A comparison of different methods for water hammer valve closure with CFD. Water 2023, 15, 1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, S.; Hanmaiahgari, P.R.; Karney, B. An overview of the numerical approaches to water hammer modelling: The ongoing quest for practical and accurate numerical approaches. Water 2021, 13, 1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergeron, L. Du Coup de Bélier en Hydraulique—Au Coup de Foudre en Electricité (Waterhammer in Hydraulics and Wave Surges in Electricity); Dunod: Paris, France, 1950. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, C.; Avellan, F.; Allenbach, P.; Sapin, A.; Simond, J.J. New Tool for the Simulation of Transients Phenomena in Francis Turbine Power Plants. In Proceedings of the 21st IAHR Symposium on Hydraulic Machinery and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 9–12 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolet, C. Hydroacoustic Modelling and Numerical Simulation of Unsteady Operation of Hydroelectric Systems. Ph.D. Thesis, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), Lausanne, Switzerland, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hadj-Taieb, L.; Hadj-Taieb, E.; Thirriot, C. Numerical simulation of transient vaporous cavitating flow in horizontal pipelines. Int. J. Model. Simul. 2007, 27, 347–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twyman, J.Q. Water hammer analysis using an implicit finite-difference method. Ingeniare Rev. Chil. Ing. 2018, 26, 307–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, D.J.; Lingireddy, S.; Boulos, P.F. Pressure Wave Analysis of Transient Flow in Pipe Distribution Systems; MWH Soft: Pasadena, CA, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Grandin, H., Jr. Fundamentals of the Finite Element Method; Waveland Press: Long Grove, IL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Chakraverty, S.; Mahato, N.R.; Karunakar, P.; Rao, T.D. Advanced Numerical and Semi-Analytical Methods for Differential Equations; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, M.; Ghidaoui, M.S. Godunov-type solutions for water hammer flows. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2004, 130, 341–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, L.; Wang, H.; Liu, D.; Ma, J.; Wang, P.; Xia, L. A second-order finite volume method for pipe flow with water column separation. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2017, 17, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seck, A.; Fuamba, M.; Kahawita, R. Finite-volume solutions to the water-hammer equations in conservation form incorporating dynamic friction using the Godunov scheme. J. Hydraul. Eng. 2017, 143, 04017029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, J.J. A finite element model and electronic analogue of pipeline pressure transients with frequency-dependent friction. J. Fluids Eng. 2003, 125, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manhartsgruber, B. On the passivity of a Galerkin finite element model for transient flow in hydraulic pipelines. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part I J. Syst. Control Eng. 2006, 220, 223–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jović, V. Analysis and Modelling of Non-Steady Flow in Pipe and Channel Networks; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Simpson, A.R.; Tijsseling, A.R. Water hammer with column separation: A historical review. J. Fluids Struct. 2006, 26, 125–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yang, J.; Guo, W.; Zeng, W.; Wang, C.; Sarrinen, L.; Norrlund, P. A mathematical model and its application for hydropower unit under different operating conditions. Energies 2015, 8, 10260–10275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, H.; Yang, J.; Fu, L. Study of Nonlinear Dynamical Model and Control Strategy of Transient Process in Hydropower Station with Francis Turbine. In Proceedings of the 2009 Asian-Pacific Power and Energy Engineering Conference, Wuhan, China, 27–31 March 2009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svingen, B.; Reines, A.F.; Nielsen, T.K.; Storli, P.T. Theoretical turbine model with hydraulic losses. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2021, 774, 012010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Almeida, A.B. Dynamic orifice model on water hammer analysis of high and medium heads of small hydropower schemes. J. Hydraul. Res. 2001, 39, 429–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, H.M.; Coronado-Hernández, O.E.; Morgado, P.A.; Simão, M. Mathematical modelling of a reversible hydropower system: Dynamic effects in turbine mode. Water 2023, 15, 2034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nielsen, T.K. Simulation model for Francis and reversible pump turbines. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2015, 8, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaeger, C. Fluid Transients in Hydro-Electric Engineering Practice; Blackie: Glasgow, UK, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, S.; Nilsson, H.; Lillberg, E.; Edh, N. An in-depth numerical analysis of transient flow field in a Francis turbine during shutdown. Renew. Energy 2021, 179, 2322–2347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, A.; Rek, Z.; Urbanowicz, K. Analytical, Numerical 1D and 3D water hammer investigations in a simple pipeline apparatus. Strojniški Vestnik—J. Mech. Eng. 2025, 71, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.R.A.; Pu, J.H.; Hanmaiahgari, P.R.; Lambert, M.F. Insights into CFD modelling of water hammer. Water 2023, 15, 3988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Fu, X.; Zuo, Z.; Wang, H.; Li, Z.; Liu, S.; Wei, X. Investigation methods for analysis of transient phenomena concerning design and operation of hydraulic-machine systems—A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2019, 101, 26–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Feng, J.; Zhao, Z.; Zhang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xu, B. A 1D-3D coupling model to evaluate hydropower generation system stability. Energies 2022, 15, 7089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherny, S.; Chirkov, D.; Bannikov, D.; Lapin, V.; Skorospelov, V.; Eshkunova, I.; Avdushenko, A. 3D Numerical simulation of transient processes in hydraulic turbines. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2010, 12, 012071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Nilsson, H.; Yang, J.; Petit, O. 1D–3D coupling for hydraulic system transient simulations. Comput. Phys. Commun. 2017, 210, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Cheng, Y. Simulation of hydraulic transients in hydropower systems using 1-D-3-D coupling approach. J. Hydrodyn. 2012, 24, 595–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, A.; Kolšek, T. Developments in Bulb Turbine Three-Dimensional Water Hammer Modelling. In Proceedings of the 21st IAHR Symposium on Hydraulic Machinery and Systems, Lausanne, Switzerland, 9–12 September 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, L. Investigation of pumped storage hydropower-off transient process using 3D numerical simulation based on SP-VOF hybrid model. Energies 2018, 11, 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandair, S. 1D and 3D Water-Hammer Models: The Energetics of High Friction Pipe Flow and Hydropower Load Rejection. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, D.; Chen, H.; Zhang, J.; Jiang, S.; Gui, J.; Yang, C.; Yu, A. Numerical study on flow characteristics in a Francis turbine during load rejection. Energies 2019, 12, 716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Yu, J.; Wu, Y. 3D Unsteady turbulent simulations of transients of the Francis turbine. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2010, 12, 012001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, A.; Bergant, A. Issues in ‘Benchmarking’ Fluid Transients Software Models. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Pressure Surges, Edinburgh, UK, 14–16 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Trivedi, C.; Dahlhaug, O.G. A comprehensive review of verification and validation techniques applied to hydraulic turbines. Int. J. Fluid Mach. Syst. 2019, 12, 345–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergant, A.; Sijamhodžić, E. Water Hammer Problems Related to Refurbishment and Upgrading of Hydraulic Machinery. In Proceedings of the Hydropower into the Next Century, Portorož, Slovenia, 15–17 September 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Sijamhodžić, E. Water Hammer Flow Regimes in a High-Head Francis Turbine Hydro Power Plant. In Proceedings of the Hydroturbo’98, Loučná nad Desnou, Czech Republic, 6–8 October 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Papler, D. 100 Let Kranjske Deželne Elektrarne ZAVRŠNICA: Od Proizvodnje Električne Energije do Spomenika Tehniške Dediščine (100 Years of the Carniolan Provincial Power Plant Završnica: From Electricity Production to a Monument of Technical Heritage); Družba Savske elektrarne: Ljubljana, Slovenia, 2015. (In Slovene) [Google Scholar]

- Mazij, J.; Bergant, A. Hydraulic transient control of refurbished Francis turbine hydropower schemes in Slovenia. J. Energy Technol. 2015, 8, 25–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPFL. Computer Package SIMSEN-Hydro v1.5; EPFL: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bergant, A.; Anderson, A.; Nicolet, C.; Karadžić, U.; Mazij, J. Issues Related to Fluid Transients in Refurbished and Upgraded Hydropower Schemes. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Pressure Surges, Lisbon, Portugal, 24–26 October 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Karadžić, U.; Bergant, A.; Vukoslavčević, P.; Sijamhodžić, E.; Fabijan, D. Water hammer caused by shut-off valves in hydropower plants. J. Energy Technol. 2011, 4, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alligné, S.; Nicolet, C.; Chabloz, P.; Chapuis, L. Dynamic closing modelling of the penstock protection valve for pipe burst simulations. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 405, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, J.; Mualla, W. Dynamic behaviour of safety butterfly valves. Int. Water Power Dam Constr. 1984, 36, 26–31. [Google Scholar]

| Subsection | hsc,max,c (m) | hsc,max,m (m) | hsc,max,Err (%) | nmax,c (m) | nmax,m (m) | nmax,Err (%) |

| 6.1. | 83.9 | 83.9 | 0 | 1036 | 1030 | +0.6 |

| 6.2. | 504.2 | 501.0 | +0.6 | 1075 | 1082 | −0.6 |

| 6.3. | 87.3 | 81.5 | +7.1 | 711.5 | 696.2 | +2.2 |

| 6.4. | 44.2 | 42.9 | +3.0 | 405.5 | 391.5 | +3.6 |

| Subsection | hv,up,c (m) | hv,up,m (m) | hv,up,Err (%) | - | - | - |

| 6.5. | 129.8 | 127.6 | 1.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bergant, A.; Mazij, J.; Pekolj, J.; Urbanowicz, K. Issues Related to Water Hammer in Francis-Turbine Hydropower Schemes: A Review. Energies 2025, 18, 6404. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246404

Bergant A, Mazij J, Pekolj J, Urbanowicz K. Issues Related to Water Hammer in Francis-Turbine Hydropower Schemes: A Review. Energies. 2025; 18(24):6404. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246404

Chicago/Turabian StyleBergant, Anton, Jernej Mazij, Jošt Pekolj, and Kamil Urbanowicz. 2025. "Issues Related to Water Hammer in Francis-Turbine Hydropower Schemes: A Review" Energies 18, no. 24: 6404. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246404

APA StyleBergant, A., Mazij, J., Pekolj, J., & Urbanowicz, K. (2025). Issues Related to Water Hammer in Francis-Turbine Hydropower Schemes: A Review. Energies, 18(24), 6404. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18246404