1. Introduction

Thermal design is a critical issue for artificial satellites, in order to meet the requirements and succeed in the spacecraft mission. Thermal management and design issues were discussed by [

1,

2], and brief examples on the thermal management of not only system-level but also equipment-level were investigated. Satellite-level thermal design considerations were studied comprehensively by [

3] in terms of subsystem electronics; some detailed analyses were handled depending on the complexity of the equipment, which required thermal validation by tests [

3,

4,

5,

6].

Satellites are composed of many subsystems, and one of the most critical subsystems is the power subsystem, which is used to supply power for the whole system during its mission. Necessary power is transformed from the sun and converted to electrical energy via solar panels as the primary energy source. However, mission requirements direct the satellite to such an orbit that continuous solar energy is not always possible or is limited due to design requirements. In this case, as a secondary energy source, a power storage system is mandatory to feed the subsystems of the spacecraft to support the energy input and accomplish the mission. Although batteries are used in a variety of areas, such as aerospace, military, and automotive at present [

7,

8,

9,

10], the use of batteries in space missions is as old as the beginning of artificial satellite history in 1957. A comprehensive classification of batteries in space missions was summarized by [

11,

12]. First commercially developed by Sony in 1991, the first Li-ion battery pack was flown with the ESA’s experimental Proba 1 mission in 2001 [

13]. Since then, Li-ion batteries have been used as a secondary power storage system because of their high specific energy, better cycle life, and high reliability with the aid of a wide temperature range [

14,

15].

Whatever the use areas, either for battery performance and cycle life, thermal effects are critical, as well as discharge rates and power profile [

16]. While a temperature decrease causes an increase in the viscosity of the electrolyte-causing lithium plating during charge [

17], a temperature increase results in capacity degradation due to increased internal resistance [

17,

18,

19]. Therefore, keeping the battery cells within certain temperature limits plays an important role in preventing any permanent damage and failure of the mission. The other critical parameter in battery design is the cell balancing [

20], in which isothermality plays an important role, which leads the designers to consider the thermal management of whole battery blocks. Since the battery cells and electronics dissipate heat, excess heat must be rejected, while the temperature of the battery interface should not exceed the lower operational temperature limit.

The thermal design and analysis of batteries are considered in the literature in detail. Li-ion battery thermal design and analysis were studied by [

21] with composite structures. Different cooling methods were elaborated by [

22] to cool the batteries using liquid cooling and phase-change materials. For communication satellites, refs. [

14,

23] worked on the thermal control of a battery supported with modeling and analysis. Testing activities were one of the verification methods for battery design, and [

24] studied the effects of test parameters that influence battery capacity degradation for space applications. Thermal design and analysis of Li-ion batteries in space applications were investigated by [

14,

25,

26,

27] for different missions, including Geostationary Orbit (GEO), Low-Earth Orbit (LEO), and other missions.

In order to understand the thermal behavior of complex systems in space, a verified thermal mathematical model (TMM) is required. The most common way of generating such a model is to generate a TMM using CAD geometry with finite element modelers, such as Ansys [

28], Patran [

29], and Siemens NX [

30]. Using the aforementioned software, studies were performed using dense-mesh finite element models [

31,

32]. However, finite element modelers were generating a huge number of elements and nodes and generating results over longer times, while analysts had to deal with modeling errors, some of which could not be detected easily. Therefore, in order to receive a rapid solution and perform sensitivity analysis with changing parameters, the detailed models must be simplified [

33]. Starting with a single node, simplified models could be helpful in order to compare the temperatures with analytical calculations [

34,

35]. Moreover, the simplified models were also useful for preliminary simulations to be aware of the thermal design of spacecraft and critical subsystems [

36]. However, simplified or reduced models are coarse and may not give information about hot spots, critical parts, or elements that dissipate heat. Therefore, the model must be customized to project not only the physical reality, such as heat flows, contacts, and boundary conditions, but also to enable the indication of critical elements or hot spots. Either reducing the FEM data or building simple models, the thermal network method is the conventional method, which is a lumped-parameter method, using the electrical network analogy and utilizes the finite-difference technique to solve the energy balance equation [

37,

38,

39]. This method was applied not only to spacecraft but also to equipment [

40,

41] and even for component-level simulations [

42].

Whatever the method is, any numerical simulation that cannot be verified by analytical calculations must be verified by a couple of testing activities. The most critical step is to be sure that the simulation model reflects the reality of the physical model, such as a structural thermal model (STM) or a flight model (FM), and perform the simulations with the correct simulation model. Therefore, in addition to thermal vacuum test activity, a thermal balance test (TBT) is essential under vacuum conditions. While TBT could be performed time-dependently and heat capacity could be corrected alongside conduction and radiation links, TBT could be performed at steady-state, just for the estimation of both conduction and radiation exchange only [

43,

44]. For model correlation, not only the test item, but also the thermal vacuum chamber and its thermal environment must be modeled properly. Temperatures from the simulation environment and the thermocouple readings were compared based on specific scenarios, including the worst-hot and worst-cold cases [

44,

45].

Consequently, this study focuses on a thermal balance test activity of a Li-ion battery STM and generates a rapid thermal model mature enough to represent each physical part using the test data. Test item, test conditions, and model derivation and correlations will be discussed in the subsequent sections of this study.

2. The Li-ion Battery

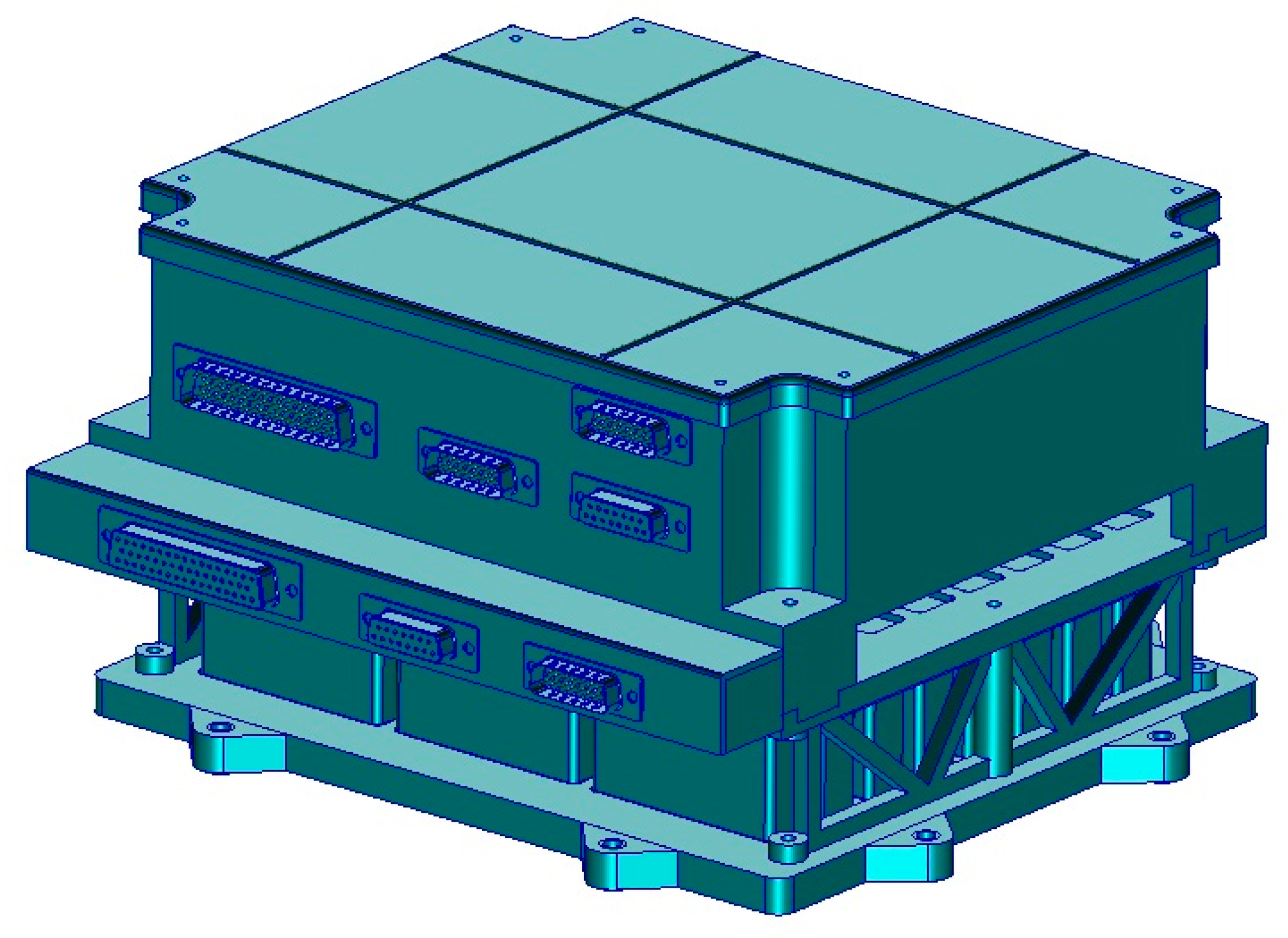

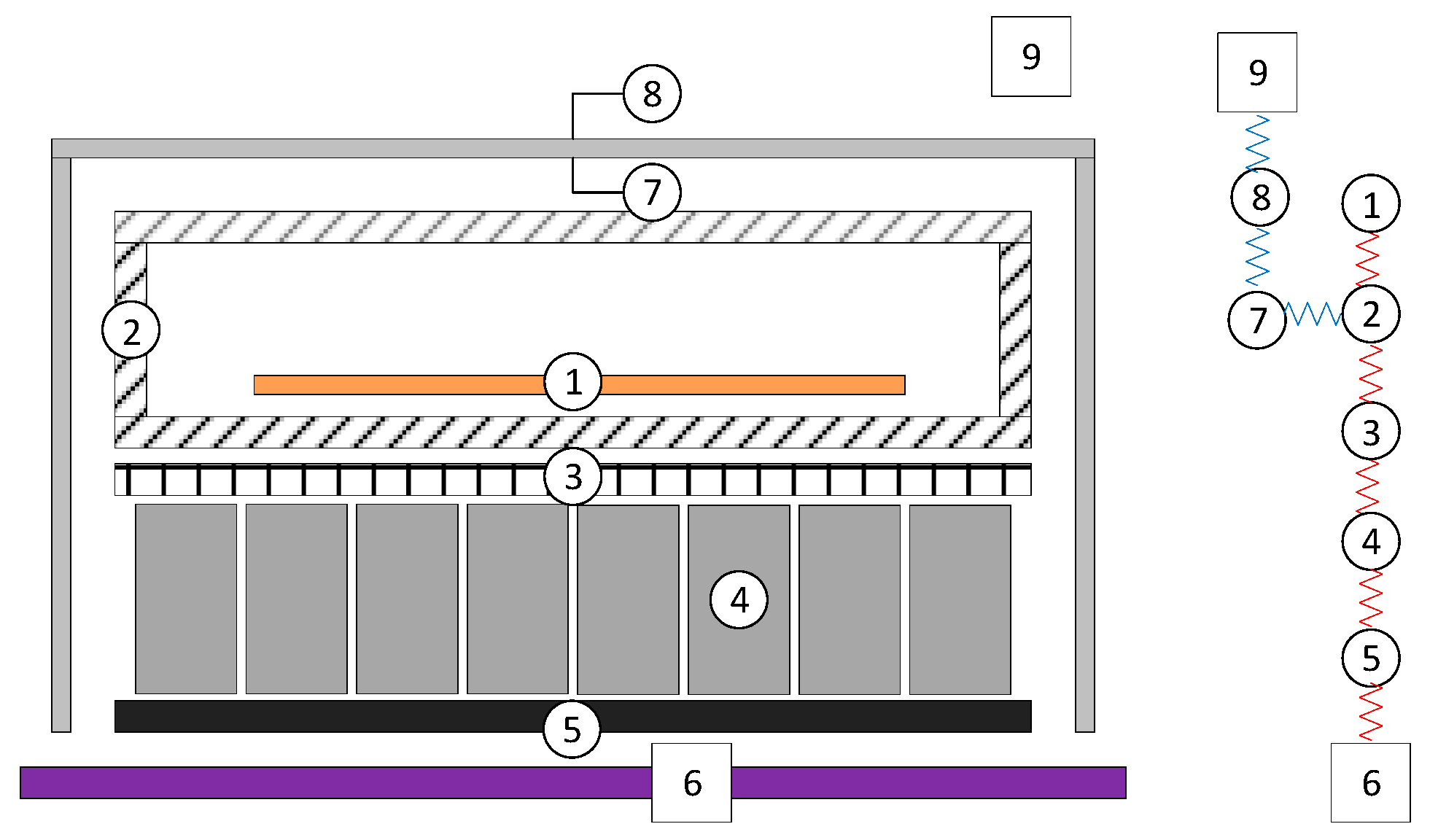

In this study, the Li-ion battery designed by TUBITAK Marmara Research Center was considered, as shown in

Figure 1.

The battery was designed for an LEO mission, and the technical properties are given in

Table 1.

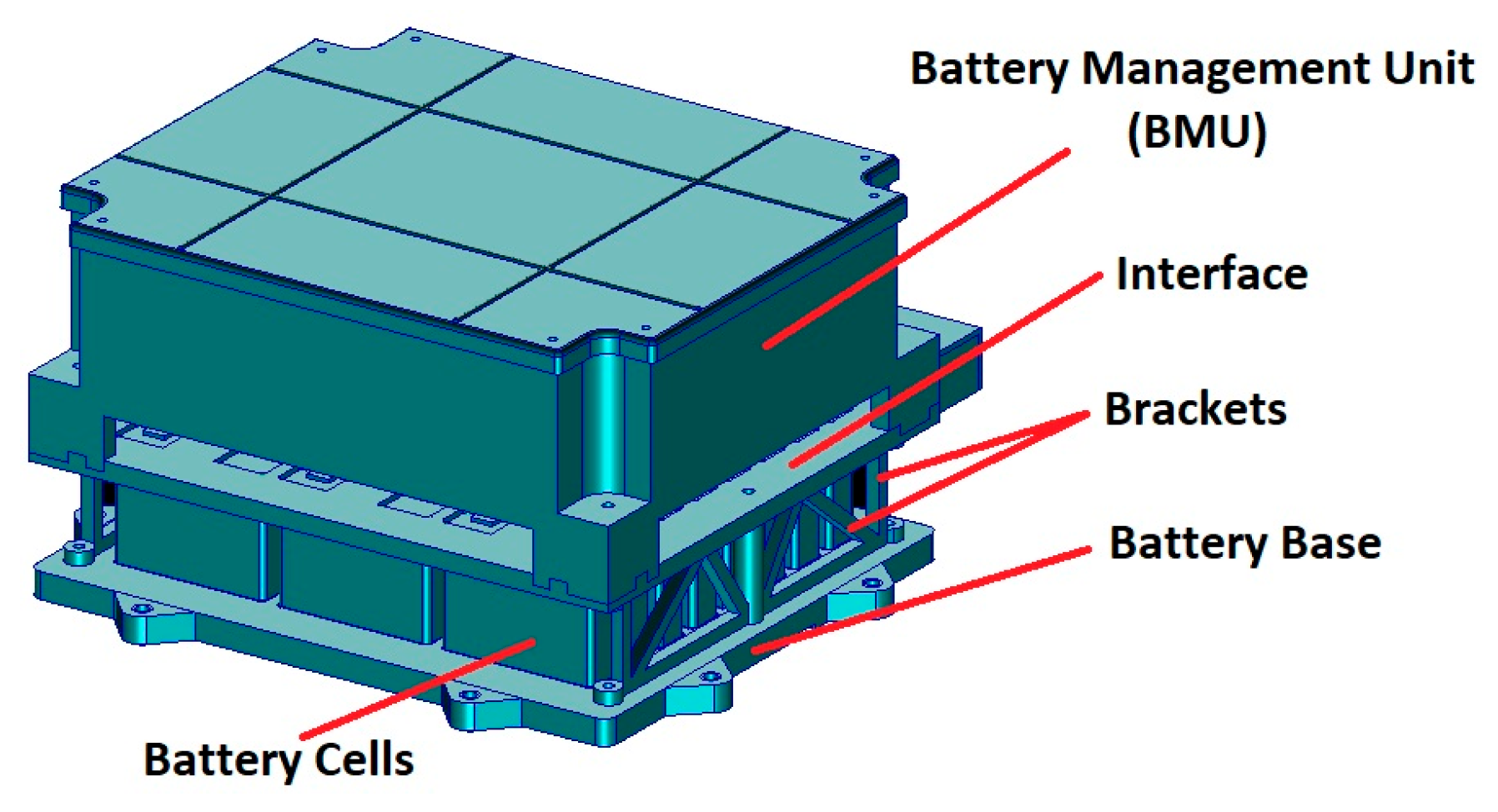

The battery is mainly composed of an electronic unit called the battery management unit (BMU), located at the top, and the battery unit, housing the battery cells at the bottom. The battery unit is separated from the electronics with an interface plate, which is made up of epoxy glass laminate, and the battery cells are also supported by the brackets, as shown in

Figure 2.

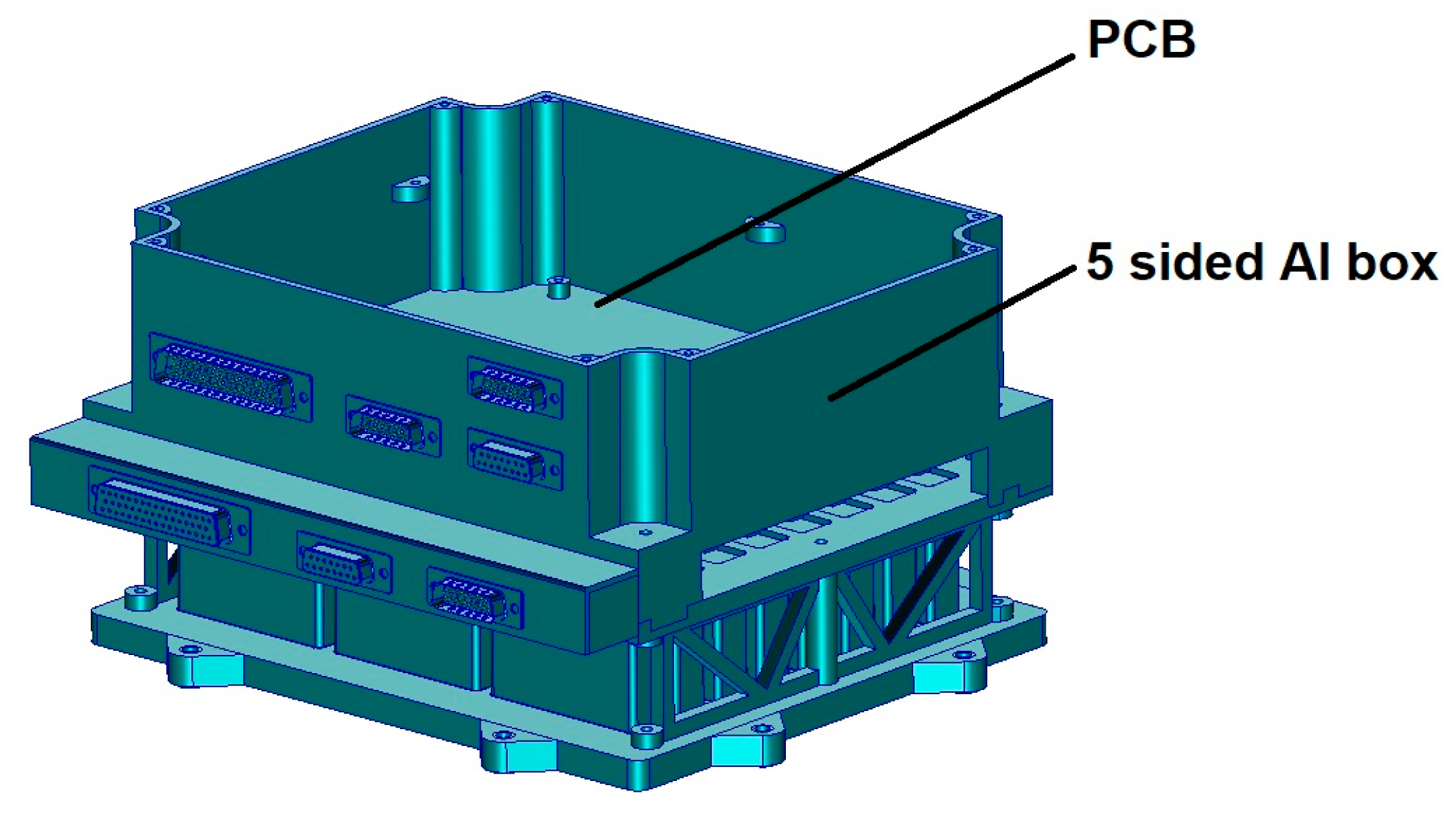

The BMU includes the five-sided Aluminum (Al) box, the PCB inside the box, and the Aluminum cover of the box at the top. In order to show the PCB, the unit without the Al cover is shown in

Figure 3.

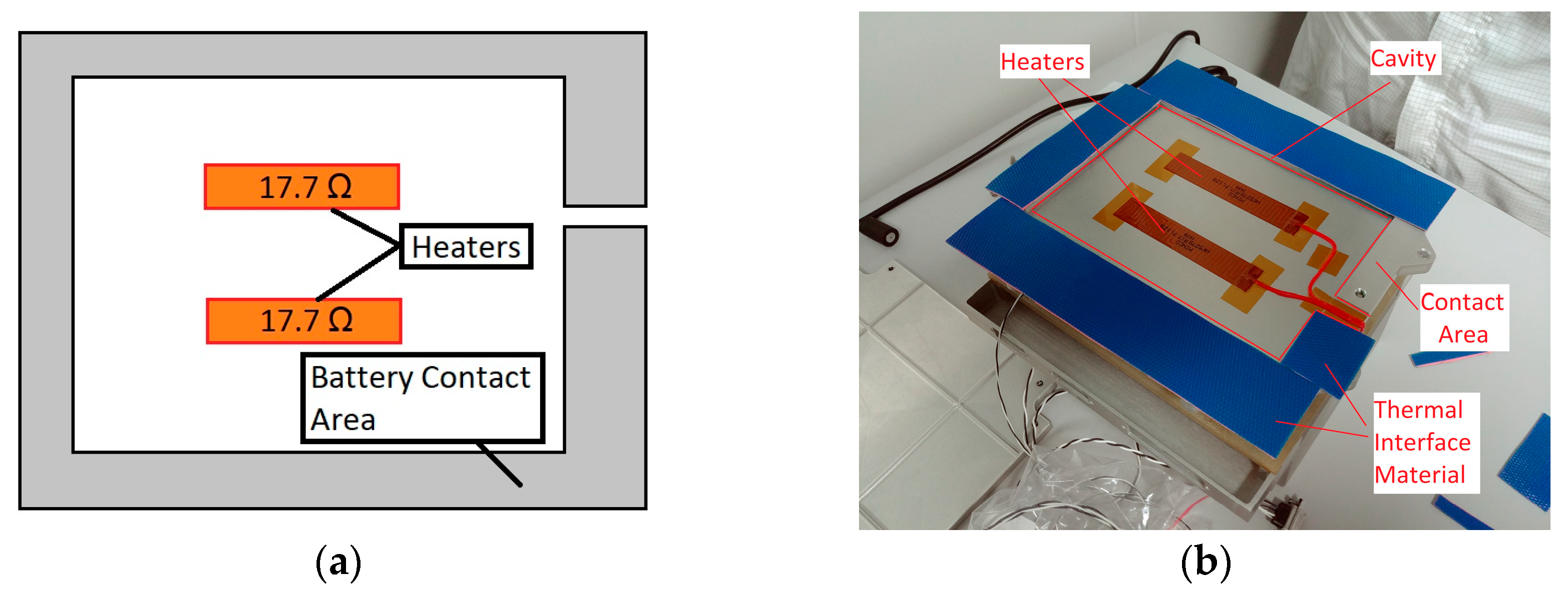

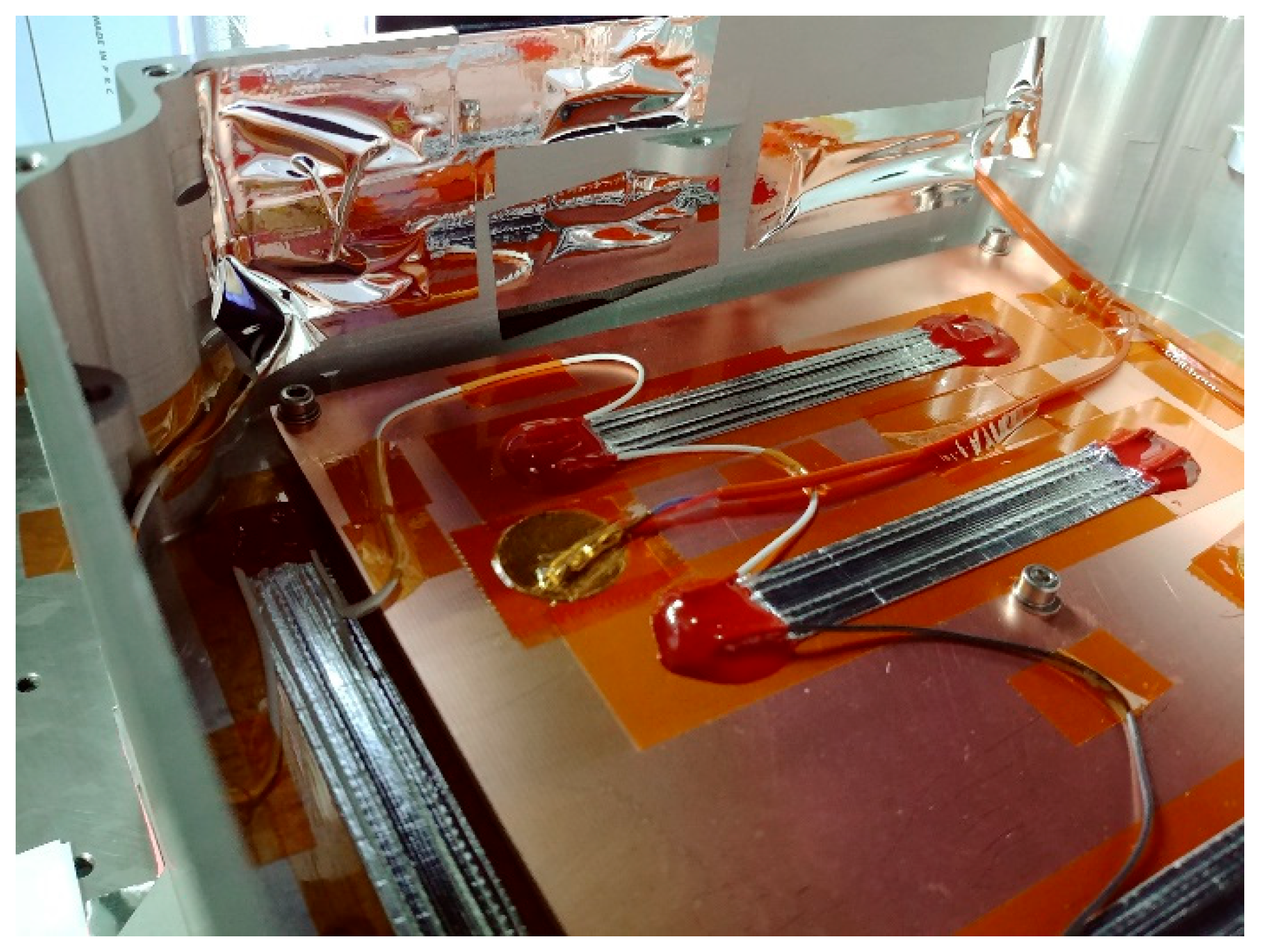

Since the BMU design was not finalized, the BMU on the structural thermal model (STM) was designed based on the maximum heat dissipation of the PCB and BMU chassis. Heat dissipation was simulated by test heaters made of Clayborn, applied on the PCB and chassis of the electronic box, as shown in

Figure 4. Three-piece test heaters were connected in a series to exert 4 W homogeneously on the PCB, in order to prevent a hot spot on the low thermal conductivity FR4 material. The heater on the Al box interior, representing the components on the BMU chassis, was supplied by another power supply and designed to give 2 W of constant power. Note that the heat dissipation of battery cells was neglected since simulating the heat dissipation of each battery cell via heaters would not be feasible and could disturb the heat flow path. Therefore, the heaters were not applied to battery cells.

The whole equipment is based on an Aluminum base with a contact area of 1.88 × 10

−2 m

2 with thermal interface material. Heaters, manufactured by Minco, are mounted inside the cavity of the base of the battery to prevent any thermal contact with the satellite interface and to heat the battery cells when necessary from a colder spacecraft interface. The placement of the heaters at the bottom side of the battery is shown in

Figure 5.

Although the battery has a different mechanical composition with anisotropic materials, especially in the battery cells, the STM of the battery was made of mainly Aluminum material (Al6061-T6). The PCB and the interface material, below the BMU and isolating the battery cells, were made of FR4 and epoxy glass, respectively. The battery cells were glued to the base via 2216 adhesive. The thermal conductivity of the materials used in the battery STM is given in

Table 2.

3. Test Preparation

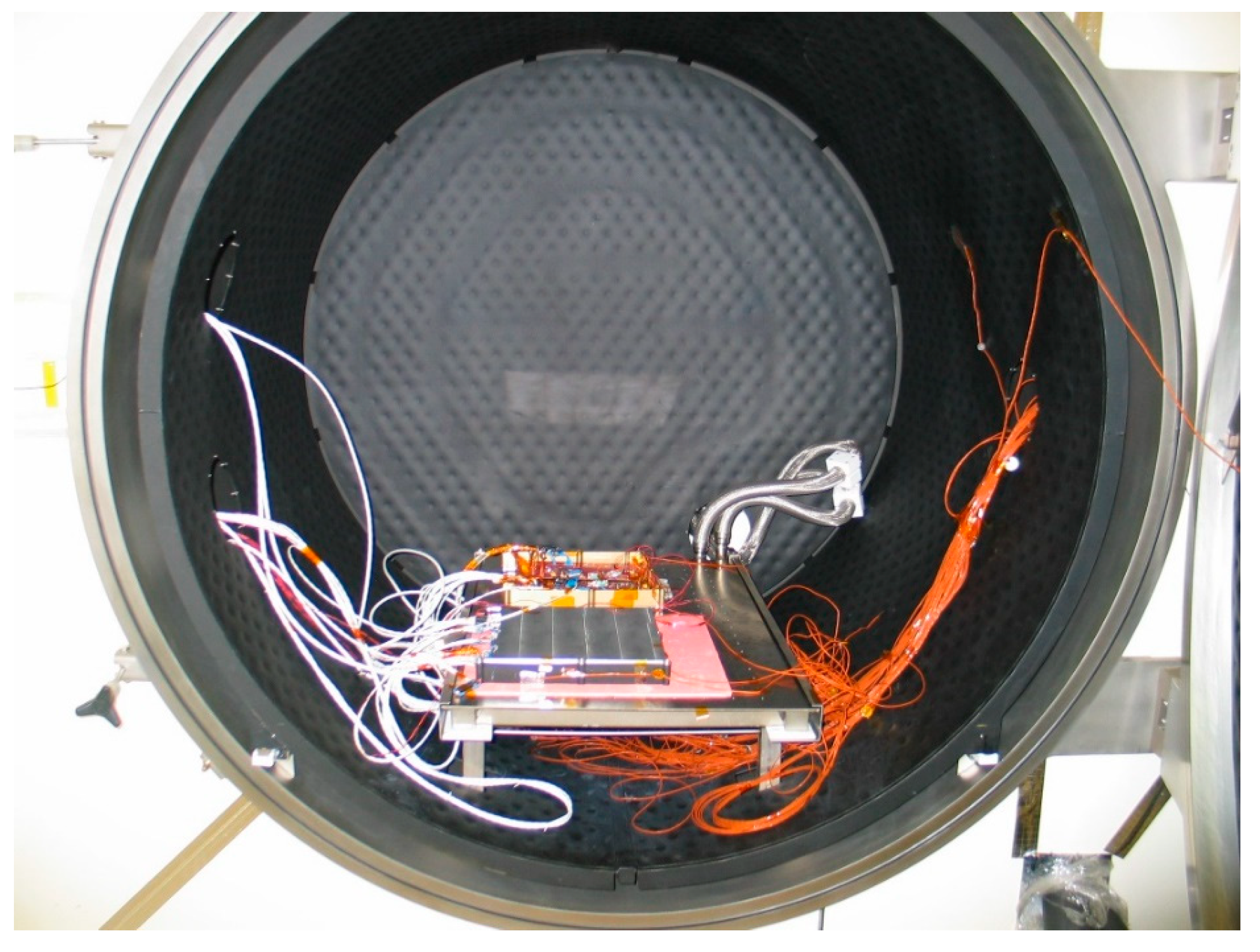

The Li-ion battery was tested in a medium-sized thermal vacuum chamber (TVAC) at the TUBITAK Space Technologies Research Institute (TUBITAK UZAY) as shown in

Figure 6.

The TVAC, which has been operational since 2007, was designed for testing not only equipment and subsystems, but also microsatellites. The chamber was used for thermal vacuum cycling tests of the RASAT microsatellite [

6]. The TVAC is a horizontal-type and has dimensions of 1200 mm in diameter and 800 mm in depth, resulting in 2100 lt of volume. The chamber has one dry pump for rough pumping up to 10

−2 mbar and one cryogenic pump, which allows for a vacuum environment less than 10

−5 mbar in 3 h at ambient temperature. TVAC also has a temperature-controlled plate and shroud (inner walls), which could be set at any temperature between −70 °C to +125 °C.

The Li-ion battery STM was covered with a 13-layer MLI blanket designed by TUBITAK UZAY as a requirement of both spacecraft missions and the battery itself to satisfy thermal radiation decoupling from the TVAC’s shroud, similar to the spacecraft interior as shown in

Figure 7. The blanket layers were composed of Mylar

® and Dacron

® netting manufactured by Dunmore (Lackawanna County, PA, USA) and raw blankets sheets were prepared by Aerothreads, Inc. (Riverdale, MD, USA).

The missing connector locations at the side walls of the BMU were also covered by Al tape to keep the MBU in an enclosure. Since the emittance of Al tape is as low as the bare Al used in the STM, no significant effect was observed from it. The Al-tape application is shown in

Figure 8.

Regarding the test configuration, 27 T-type thermocouples were applied on the battery STM as shown in

Figure 9. The thermocouples have an accuracy of ±1 °C.

The thermocouple locations associated with thermocouple numbers (nr.) are listed in

Table 3.

6. Model Correlation

For model correlation, the basic heat transfer is discretized with conduction and radiation terms per node to set up a reduced thermal mathematical model [

37,

46]:

In this equation, is the heat generation, k is the thermal conductivity, ρ is the density, Cp is the specific heat, T is the temperature, and t refers to time.

When this equation is discretized for conduction and radiation terms, one could obtain the heat transfer equation:

where

Ki,j and

Ri,j are the conduction and radiation conductors between nodes

i and

j, respectively:

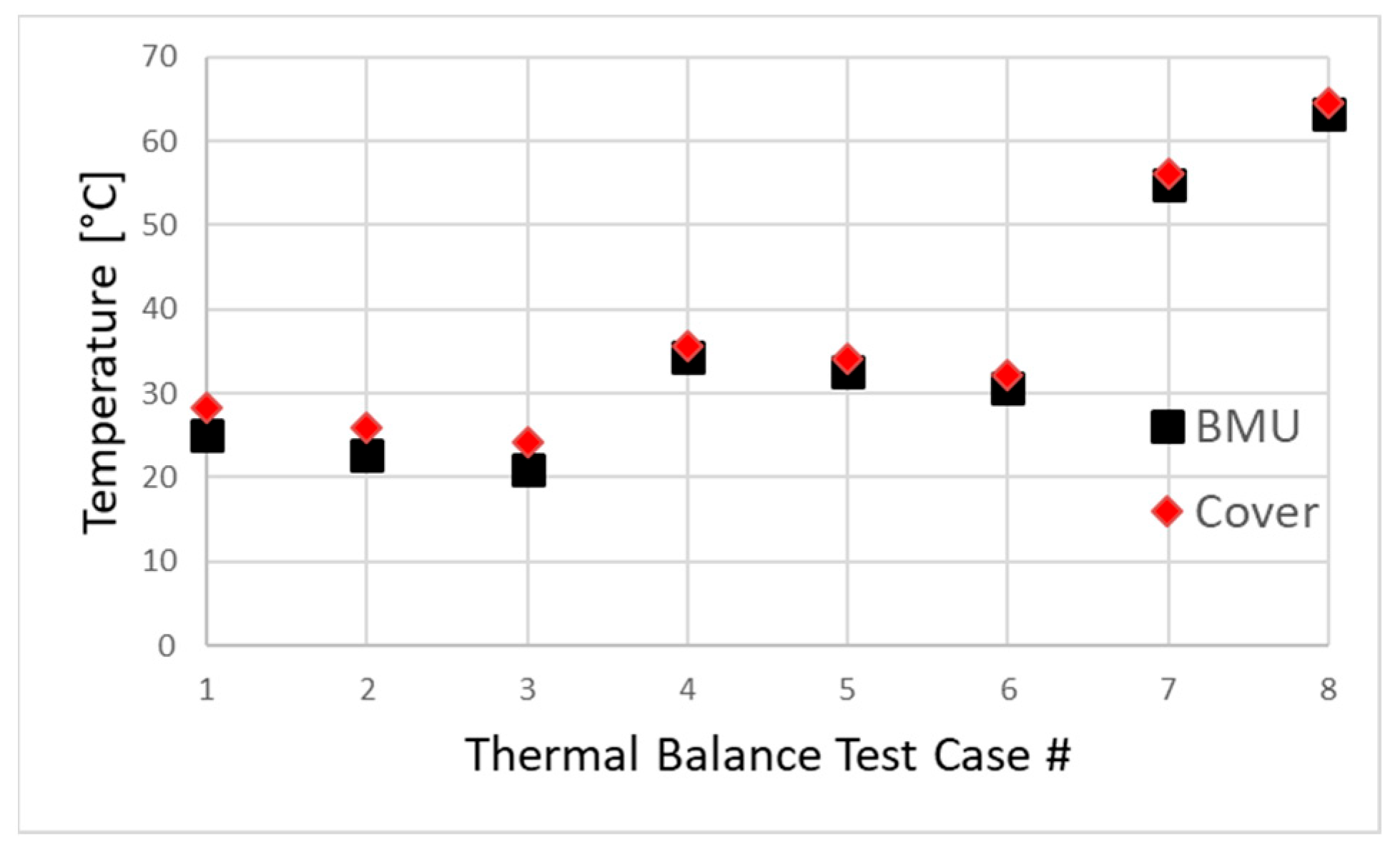

Based on the TBT results per test scenarios, the steady-state temperatures of seven major parts of the battery block could be discretized by seven nodes. However, during TBT, both temperature variations and steady-state temperatures given in

Table 5 indicated that some of the major parts’ temperatures were very close. Therefore, these nodes were investigated as below for an update before setting up the nodal network.

The first point is the temperature of the BMU and its cover. Although two parts were assembled to each other with dry contact, the distribution in the STM parts indicated that the temperature of some of the parts had a similar response. The temperature difference between the BMU and cover, per the test scenario, is shown in

Figure 10. As could be seen from this figure, the maximum error occurs between test cases 1 and 3, since the TVAC is at minimum while the Li-ion battery was dissipating a constant power of 6 W. Taking operational and non-operating temperature extremes, such as 0 °C to +40 °C, of the interface into consideration, one could look to test cases 4 to 8, which had very small error < 0.5%. Thus, BMU and cover temperature are merged into a single node, behaving as a single part.

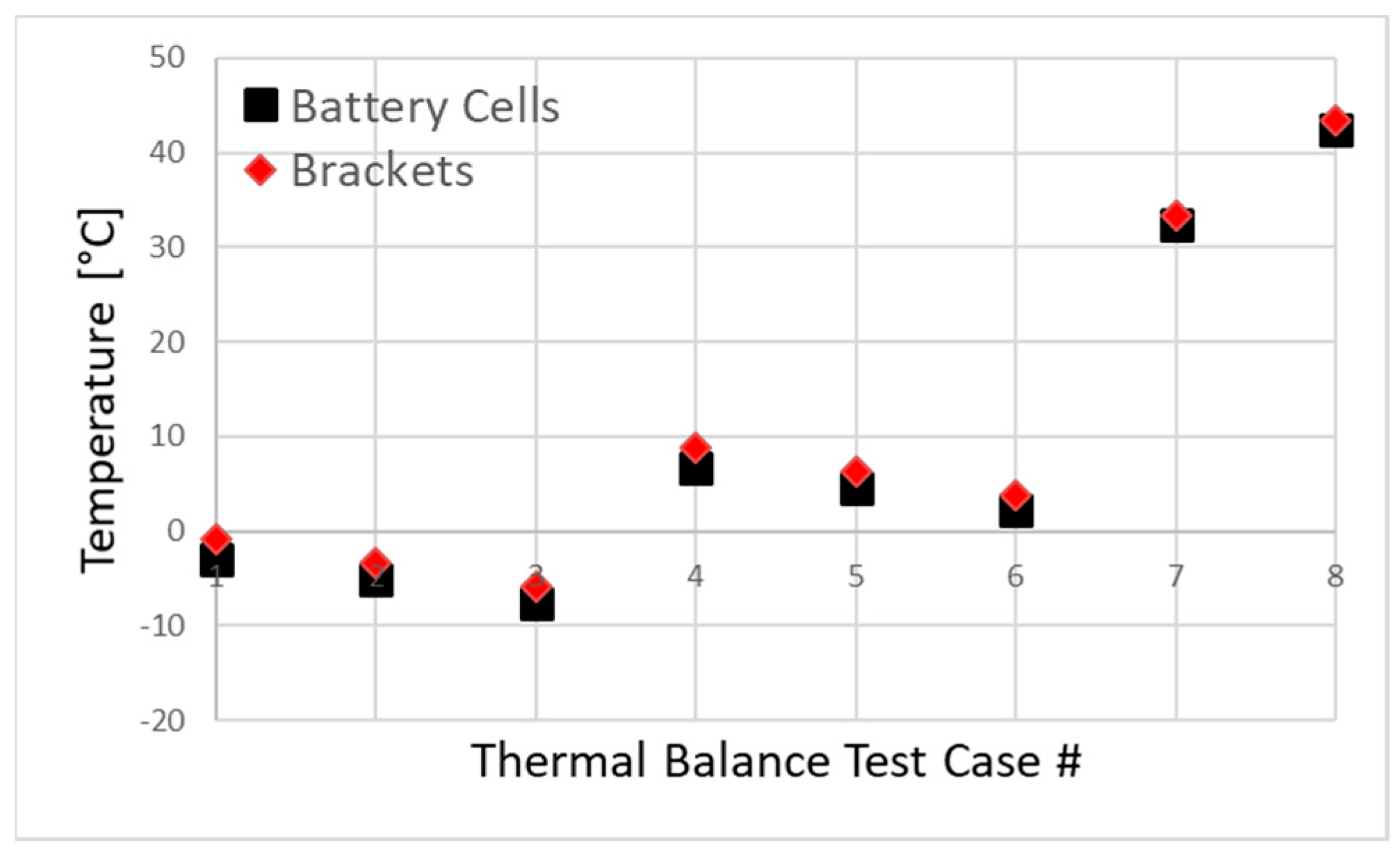

The second point was the cells and brackets. Although Li-ion battery cells are the most critical parts of the battery block, and the temperature ranges given in

Table 1 were dedicated to the battery cells, all the scenarios indicated that the brackets between the epoxy glass interface plate and the battery base also have similar temperature variations when compared to the cells. The steady-state temperature difference between the Li-ion cells and the brackets is given in

Figure 11. When comparing the eight test cases, the temperature difference between the brackets and the cells is also very small, with a maximum error of <1%.

Based on similar responses for two coupled parts, a 5-node thermal mathematical model was constructed to simulate the thermal behavior of a Li-ion battery. The nodal description of the nodes is tabulated in

Table 6, and an illustration of the nodal network is presented in

Figure 12. Note that node 6 is a boundary node, representing the cold plate of the TVAC.

The MLI used in TBT was a 2 Mil Mylar VDA2 with an inner and outer layer and an interior of 11 layers of 0.25 Mil Mylar VDA2, making a 13-layered MLI blanket with a surface emittance of ε = 0.02. Since the temperature of the MLI interior was close to the BMU temperature and the exterior surface temperature was close to the shroud temperature, as tabulated in

Table 5, the effective emissivity ε

eff of the MLI blanket was taken as calculated values in the literature [

1], which was 0.03. As a consequence of effective insulation, the effect of the shroud on the battery was neglected, and the MLI radiatively decoupled the battery from the shroud for the first cycle of simulations.

7. Correlation Results and Discussion

Based on the 5-node TMM outlined in

Table 6, with updated nodes 2 and 4, conduction conductors were calculated via test results and based on the thermal link indicated in

Figure 12. The conduction conductors calculated for each test case are given in

Figure 13.

Based on the analysis results, three correlation success criteria were sought based on ECSS-E-ST-31C:

ΔT < 5 K for the interior part

Temperature mean deviation within ±2 K

Temperature standard deviation <3 K, 1σ

As shown in the tables, a correlation success criterion was met for cases 1–6; however, for cases 7 and 8, the temperature differences for node 1 exceed the limits, because radiative heat transfer is significantly dominant with the fourth power of temperature defined in Equation (2).

As shown in

Table 13 and

Table 14, for cases 7 and 8, the temperature of the PCB was calculated as 82.5 °C and 92.5 °C, respectively, with a temperature deviation of 6.6 °C and 9.2 °C, due to a lack of radiation conductors. Moreover, in test case 8, the BMU temperature was calculated as 69.4 °C, which violated the temperature deviation requirement with 5.5 °C > 5 °C.

Since the nodes in which the model correlation was not satisfied were the ones with high temperatures and a lack of radiation conductors, as a second iteration, the MLI was included, resulting in three radiation conductors added to TMM: between MLI interior and BMU, between MLI interior and exterior, and between MLI exterior and the shroud. The final 9-node TMM with a 7-node Li-ion battery TMM is presented in

Figure 14.

The MLI was modeled at 0.02 for surface emittance, and radiation conductors were calculated using the ε and surface area, including a view factor of 1 for BMU–MLI and MLI–shroud radiation link calculations.

The final simulation proves model correlation for test cases 4 to 8, while still improving on the TMM, as was necessary for test cases 1–3. Fortunately, based on

Table 1, the test cases do not project the operational or non-operating temperature of the Li-ion battery, and when test cases at 0 °C, 30 °C, and 40 °C are taken into account, the maximum deviation per node does not exceed 5 °C (4.88 °C for PCB) for test case 6.

8. Conclusions

In this study, a thermal mathematical model generation for a Li-ion battery STM was conducted, which was designed as a secondary energy source for a low-Earth orbit satellite. The STM, which was FM-representative, was designed and manufactured based on hardware almost identical to the flight model. The heat dissipation on each of the battery cells could not be implemented on the STM because of the limited accessibility to each cell and low heat dissipation. However, this difference had a negligible effect because of the heat dissipation of the BMU. TBT was applied to the model, which was identical to the flight model, in terms of structural and thermal design. Eight different test configurations were planned with different spacecraft interior environments. A reduced TMM was established based on the calculation of conduction conductors per thermal balance test data, and nodal temperatures were calculated by averaging the thermocouple data. Based on the conductor predictions, thermal simulations were performed using the thermal network method. The conduction-based thermal model was initially set up based on thermocouple data, since narrow temperature ranges within the battery block could suppress thermal radiation. However, it was seen that due to high temperature differences at 30 °C and 40 °C test environments, deviations were observed from the test results, resulting in an update with radiation conductors. The final results indicated that the final mathematical correlation was satisfied with test cases 4 to 8, which cover the operational and non-operational temperature limits of the Li-ion battery. The results also proved that the thermal requirements of both the PCB and the battery cells could well satisfy the requirements in a dedicated satellite thermal environment.