Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors as a Driver of Development of Nuclear Technologies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Advantages of Modular Nuclear Reactors

- Ultra-small modular reactors uSMRs, up to 50 MWe), used mainly in isolated areas, remote industrial sites, military bases and other areas with limited access to centralised power.

- SMR (50 to 300 MWe)—a balanced solution combining sufficient power with mobility, suitable for a wider range of applications, including power supply to small towns, industrial facilities and infrastructure.

| Reactor Name | Country | Power | Type | State |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seaborg CMSR | Denmark | <50 MWe | Liquid salt | Under development |

| USNC MMR | USA/Canada | 15 MWe | Gas-cooled, VTGR | Demonstration project |

| Oklo Aurora | USA | 1.5 MWe | Fast on metal | Development is suspended |

| TAP | USA | <50 MWe | Liquid salt | Cancelled project |

| Megapower | USA | 5 MWe | Metal-cooled | Development completed (military use) |

| NuScale VOYGR Power Module | USA | 77 MWe | Water–water | Licenced, in progress |

| SMART | Republic of Korea | 100 MWe | Water–water | Ready for construction |

| CAREM | Argentina | 32–125 MWe | Water–water | Construction of the first block |

| ACP100 | China | 125 MWe | Water–water | Construction |

| RITM-200 | Russia | 55 MWe | Water–water | In operation (on ships) |

| BANDI-60S | Republic of Korea | 60 MWe | Water–water | Development |

| Flexblue | France | ~160 MWe | Underwater, water–water | Concept |

| Holtec SMR-160 | USA | 160 MWe | Water–water | At the licencing stage |

| ARC-100 | Canada/USA | 100 MWe | Fast, sodium | Development |

| GE Hitachi BWRX-300 | USA/Japan | 300 MWe | Boiling water–water | Licencing |

| X-energy Xe-100 | USA | 80 × 4 = 320 MWe | Gas-cooled, VTGR | Development |

| SVBR-100 | Russia | 100 MWe | Fast, lead-bismuth | The project is suspended |

| Reactor Type | Key Safety Features | Potential Accident Scenarios/Challenges |

|---|---|---|

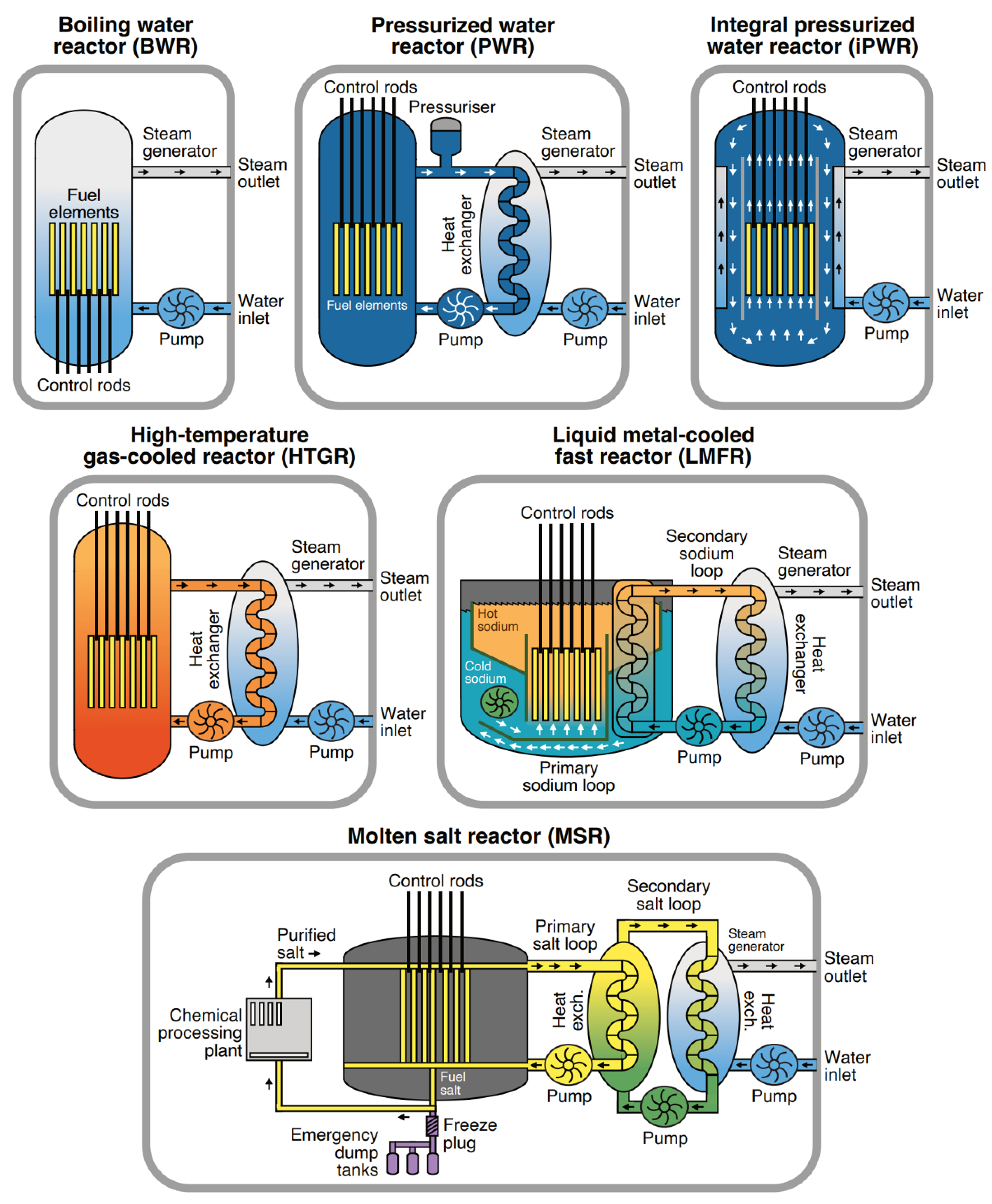

| Water-cooled SMRs (PWR, BWR, iPWR) | Proven technology, passive cooling systems, robust containment, low-enriched UO2 fuel | Loss-of-coolant accidents (LOCA), need for reliable emergency core cooling, residual heat removal in station blackout |

| HTGRs | TRISO fuel with high fission-product retention, low power density, strong passive decay heat removal | Graphite oxidation in air ingress, helium leakage, structural integrity at very high temperatures |

| LMFRs, sodium, lead-bismuth | Excellent heat transfer, natural circulation, potential for inherent shutdown response | Sodium fires and sodium-water reactions, lead-bismuth corrosion, polonium-210 radio-toxicity |

| MSRs | Low-pressure operation, negative temperature coefficients, drain tanks for passive shutdown | Corrosion of structural materials, complex salt chemistry, potential release of volatile fission products |

3. Small Modular Reactors on Low-Enriched Fuel

- Reliability and technological maturity. LEU fuel has been widely used in the power industry for decades. This experience reduces risks when introducing new reactors and speeds up the licencing and operation process.

- Ready infrastructure. LEU-fuel production and supply rely on existing and certified chains, from uranium enrichment plants to fuel assembly fabrication factories.

- Serialisation and standardisation. Thanks to standardised designs, LEU reactors can be mass-produced, which significantly reduces their cost and facilitates logistics for deployment in different countries and regions.

- Export control compliance. Unlike HEU or reprocessed fuel reactors, LEU plants are easier to align with international non-proliferation regulations, including nuclear material control treaties.

- Application flexibility. Due to their compactness, high safety and autonomy, these reactors are suitable for remote communities, small towns, and industrial sites and can complement renewable sources in hybrid energy systems.

- Multifunctionality. LEU reactors can provide not only electricity but also heat, making them effective for district heating, seawater desalination and industrial applications—especially in environments where reliable and sustainable energy is needed.

4. Small Modular Reactors Using Highly Enriched Fuel

5. Small Modular Reactors Using Thorium Fuel

6. Small Modular Reactors on Metallic Fuel and Reprocessed Fuel

7. Comparative Characteristics of Small-Scale Reactor Technologies and Future Integration with Artificial Intelligence

8. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gao, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wei, L.; Pan, P. Performance Assessment of a Multiple Generation System Integrating Sludge Hydrothermal Treatment with a Small Modular Nuclear Reactor Power Plant. Energy 2025, 315, 134323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Novotný, V.; Kim, J.; Cho, S.-B.; Rigby, A.; Saeed, R.M. Nuclear-Based Combined Heat and Power Industrial Energy Parks—Application of High Temperature Small Modular Reactors. Energy Convers. Manag. X 2025, 26, 101012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mignacca, B.; Locatelli, G. Economics and Finance of Small Modular Reactors: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2020, 118, 109519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.I. Review of Small Modular Reactors: Challenges in Safety and Economy to Success. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2024, 41, 2761–2780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, T.H.; Kim, Y.I. Microgrid Control Incorporated with Small Modular Reactor (SMR)-Based Power Productions in the University Campus. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 183, 105678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Bingham, C.; Mancini, M. Small Modular Reactors: A Comprehensive Overview of Their Economics and Strategic Aspects. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2014, 73, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingersoll, D.T. Deliberately Small Reactors and the Second Nuclear Era. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2009, 51, 589–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carlson, L.; Miller, J.; Wu, Z. Implications of HALEU Fuel on the Design of SMRs and Micro-Reactors. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 389, 111648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michaelson, D.; Jiang, J. Review of Integration of Small Modular Reactors in Renewable Energy Microgrids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 152, 111638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman Ishraq, M.A.; Shelley, A.; Sardar, M.R. Neutronic and Thermal Performance Analysis of Advanced Cladding Materials for ACP-100 SMR. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2025, 440, 114142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kindra, V.O.; Rogalev, A.N.; Kovalev, D.S.; Ilin, I.V.; Levina, A.I. Research and Development of High Temperature Gas-Cooled Reactor Nuclear Power Plants for Combined Production of Electricity, Heat and Hydrogen. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2025, 148, 149968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pal, U.K.; Zhang, C. Phase-Based Safety Review of Micro and Small Modular Reactors from Design to Decommissioning. Saf. Sci. 2025, 188, 106882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanatta, M.; Patel, D.; Allen, T.; Cooper, D.; Craig, M.T. Technoeconomic Analysis of Small Modular Reactors Decarbonizing Industrial Process Heat. Joule 2023, 7, 713–737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves, N.; Silva, C.A.M.; Lorduy-Alós, M.; Gallardo, S.; Pereira, C.; Verdú, G. Neutronic Assessment of Stable Salt Reactor with Reprocessed Fuels. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 218, 111383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinoya, C.L.; Ubando, A.T.; Culaba, A.B.; Chen, W.-H. State-of-the-Art Review of Small Modular Reactors. Energies 2023, 16, 3224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subki, H. Advances in Small Modular Reactor Technology Developments. In IAEA-NPTD Webinar on Advances in Small Modular Reactor (SMR) Design and Technology Developments. A Booklet Supplement to the IAEA Advanced Reactors Information System (ARIS); International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2020; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Popov, O.; Finin, G.; Ivaschenko, T.; Iatsyshyn, A.; Hrushchynska, N. Current State and Prospects of Smallmodule Reactors Application in Different Countries of the World. In Systems, Decision and Control in Energy IV: Volume II. Nuclear and Environmental Safety; Zaporozhets, A., Popov, O., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 3–21. ISBN 978-3-031-22500-0. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews, S.Y.Y.; Kuntjoro, Y.D.; Yusgiantoro, P. The Usage of Micro Modular Nuclear Reactors on Military Headquarters as a Prospective Solution to Achieve Energy Security and Improve National Defense. East Asian J. Multidiscip. Res. 2023, 2, 627–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comparison of the Potential Risk Associated with Various SMR Designs. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/391260763_Comparison_of_the_potential_risk_associated_with_various_SMR_designs (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Dong, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Dong, Y.; Shi, L.; Huang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Jiang, D. Testing the Feasibility of Multi-Modular Design in an HTR-PM Nuclear Plant. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 2778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, C. Research Progress on Liquid Metal Corrosion Behavior of Structural Steels for Lead Fast Reactor. J. Chin. Soc. Corros. Prot. 2023, 43, 1216–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chisholm, B.M.; Krahn, S.L.; Sowder, A.G. A Unique Molten Salt Reactor Feature–The Freeze Valve System: Design, Operating Experience, and Reliability. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 368, 110803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, H.; Peng, M.; Wang, H.; Rasool, A. Autonomous Control Model for Emergency Operation of Small Modular Reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 190, 109874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Locatelli, G.; Boarin, S.; Pellegrino, F.; Ricotti, M.E. Load Following with Small Modular Reactors (SMR): A Real Options Analysis. Energy 2015, 80, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Usman, S. Advanced and Small Modular Reactors’ Supply Chain: Current Status and Potential for Global Cooperation. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 184, 105661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, Y.; Arunachalam, M.; Elmakki, T.; Al-Ghamdi, A.S.; Bassi, H.M.; Mohammed, A.M.; Ryu, S.; Yong, S.; Shon, H.K.; Park, H.; et al. Evaluating the Economic and Environmental Viability of Small Modular Reactor (SMR)-Powered Desalination Technologies against Renewable Energy Systems. Desalination 2025, 602, 118624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishaq, M.; Dincer, I. A Clean Hydrogen and Electricity Co-Production System Based on an Integrated Plant with Small Modular Nuclear Reactor. Energy 2024, 308, 132834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs): A Review of Current Challenges and Future Applications-Chemical Communications (RSC Publishing). Available online: https://pubs.rsc.org/en/content/articlelanding/2024/cc/d4cc03980g (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- A Comprehensive Review of Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator. A B S T R C T. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/360719626_A_comprehensive_review_of_Radioisotope_Thermoelectric_Generator_A_B_S_T_R_C_T (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Hidayatullah, H.; Susyadi, S.; Subki, M.H. Design and Technology Development for Small Modular Reactors–Safety Expectations, Prospects and Impediments of Their Deployment. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2015, 79, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, E.M.A. Emerging Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors: A Critical Review. Phys. Open 2020, 5, 100038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.U.-D.; Khan, R. Techno-Economic Assessment of a Very Small Modular Reactor (vSMR): A Case Study for the LINE City in Saudi Arabia. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2023, 55, 1244–1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mays, G.T. 14-Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of the USA. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors; Carelli, M.D., Ingersoll, D.T., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2015; pp. 353–377. ISBN 978-0-85709-851-1. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, E.; Lee, J. Social Acceptance of Small Modular Reactor (SMR): Evidence from a Contingent Valuation Study in South Korea. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, H.; Wu, G.; He, F.; Tong, J.; Zhang, L. Study on the Costs and Benefits of Establishing a Unified Regulatory Guidance for Emergency Preparedness of Small Modular Reactors in China. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2023, 161, 104722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieser, E.; Clarno, K.; Haas, D.; Webber, M.E. The Economics of Small Modular Reactors at Coal Sites: A Program-Level Analysis within the State of Texas. Energy Policy 2025, 202, 114572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okubo, T. 17-Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of Japan. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors, 2nd ed.; Ingersoll, D.T., Carelli, M.D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2014; pp. 409–424. ISBN 978-0-12-823916-2. [Google Scholar]

- Beliavskii, S.; Alhassan, S.; Danilenko, V.; Karvan, R.; Nesterov, V. Effect of Changing the Outer Fuel Element Diameter on Thermophysical Parameters of KLT-40S Reactor Unit. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2023, 190, 109877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beliavskii, S.V.; Nesterov, V.N.; Laas, R.A.; Godovikh, A.V.; Bulakh, O.I. Effect of Fuel Nuclide Composition on the Fuel Lifetime of Reactor KLT-40S. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 360, 110524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyildiz, E.; Yildirim, B.; Erdogan, M.; Aydin, N. Strategic Site Selection Methodology for Small Modular Reactors: A Case Study in Türkiye. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2025, 215, 115545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, S.; Huang, G.; Zhang, X.; Han, D. Small Modular Reactors Enable the Transition to a Low-Carbon Power System across Canada. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2022, 169, 112905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Hee, N.; Peremans, H.; Nimmegeers, P. Economic Potential and Barriers of Small Modular Reactors in Europe. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2024, 203, 114743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmastro, D.F. 14-Small Modular Reactors (SMRs): The Case of Argentina. In Handbook of Small Modular Nuclear Reactors, 2nd ed.; Ingersoll, D.T., Carelli, M.D., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2021; pp. 359–373. ISBN 978-0-12-823916-2. [Google Scholar]

- Xing, M.; Fan, J.; Shen, F.; Lu, D.; Li, L.; Yu, H.; Fan, J. Comparative Analysis on the Characteristics of Liquid Lead and Lead–Bismuth Eutectic as Coolants for Fast Reactors. Energies 2025, 18, 596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sunarto; Santosa, S.; Khotimah, K.; Sriyana. Study on the Implementation of Quality Assurance Aspect on High-Temperature Gas Cooled Reactor (HTGR). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 2048, 012022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lead-Cooled Fast Reactors (LFRs)-Book Chapter-IOPscience. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/book/mono/978-0-7503-6069-2/chapter/bk978-0-7503-6069-2ch12 (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Lim, S.G.; Nam, H.S.; Lee, D.H.; Lee, S.W. Design Characteristics of Nuclear Steam Supply System and Passive Safety System for Innovative Small Modular Reactor (i-SMR). Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2025, 57, 103697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirian, B.; Asad, A.; Krezan, L.; Yakout, M.; Hogan, J.D. A New Perspective on the Mechanical Behavior of Inconel 617 at Elevated Temperatures for Small Modular Reactors. Scr. Mater. 2025, 261, 116605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Liu, M.; Xu, Z.; Liu, L.; Cao, J. Numerical Study of Forced Circulation and Natural Circulation Transition Characteristics of a Small Modular Reactor Equipped with Helical-Coiled Steam Generators. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2025, 183, 105672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Atomic Energy Agency. Safety Design Features of CAREM. In Design Features to Achieve Defence in Depth in Small and Medium Sized Reactors; International Atomic Energy Agency: Vienna, Austria, 2009; pp. 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- 2023 IAEA Annual Report Presented to the UN General Assembly. Available online: https://www.iaea.org/newscenter/news/2023-iaea-annual-report-presented-to-the-un-general-assembly (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Nøland, J.K.; Hjelmeland, M.; Hartmann, C.; Tjernberg, L.B.; Korpå, M. Overview of Small Modular and Advanced Nuclear Reactors and Their Role in the Energy Transition. IEEE J. Mag. 2025, 40, 1933–1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, N.R.; Worrall, A.; Todosow, M. Impact of Thermal Spectrum Small Modular Reactors on Performance of Once-through Nuclear Fuel Cycles with Low-Enriched Uranium. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2017, 101, 166–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamarudin, N.A.Z.; Ismail, A.F.; Rabir, M.H.; Kok Siong, K. Neutronic Optimization of Thorium-Based Fuel Configurations for Minimizing Slightly Used Nuclear Fuel and Radiotoxicity in Small Modular Reactors. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 2641–2649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abushamah, H.A.S.; Burian, O.; Ray, D.; Škoda, R. Integration of District Heating Systems with Small Modular Reactors and Organic Rankine Cycle Including Energy Storage: Design and Energy Management Optimization. Energy Convers. Manag. 2024, 322, 119138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeHart, M.D.; Karriem, Z.; Pope, M.A.; Johnson, M.P. Fuel Element Design and Analysis for Potential LEU Conversion of the Advanced Test Reactor. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2018, 104, 117–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Kwon, O.-S.; Bentz, E.; Tcherner, J. Evaluation of CANDU NPP Containment Structure Subjected to Aging and Internal Pressure Increase. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2017, 314, 82–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.G.; Wisudhaputra, A.; Lee, J.-H.; Kim, K.; Park, H.-S.; Jeong, J.J. Development of a Special Thermal-Hydraulic Component Model for the Core Makeup Tank. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2022, 54, 1890–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishraq, M.A.R.; Rohan, H.R.K.; Kruglikov, A.E. Neutronic Assessment and Optimization of ACP-100 Reactor Core Models to Achieve Unit Multiplication and Radial Power Peaking Factor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2024, 205, 110588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nam, S.H.; Venneri, P.; Kim, Y.; Chang, S.H.; Jeong, Y.H. Preliminary Conceptual Design of a New Moderated Reactor Utilizing an LEU Fuel for Space Nuclear Thermal Propulsion. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2016, 91, 183–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schickler, R.A.; Marcum, W.R.; Reese, S.R. Comparison of HEU and LEU Neutron Spectra in Irradiation Facilities at the Oregon State TRIGA® Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2013, 262, 340–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raposio, R.; Thorogood, G.; Czerwinski, K.; Rozenfeld, A. Development of LEU-Based Targets for Radiopharmaceutical Manufacturing: A Review. Appl. Radiat. Isot. 2019, 148, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, X.; Huning, A.J.; Burek, J.; Guo, F.; Kropaczek, D.J.; Pointer, W.D. The Pursuit of Net-Positive Sustainability for Industrial Decarbonization with Hybrid Energy Systems. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 362, 132349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holmström, S.; Baumeister, B.; Wight, J. Qualification of Advanced LEU Fuels for High-Power Research Reactor Conversion Designs. EPJ Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2025, 11, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Calculation of the Campaign of Reactor RITM-200-IOPscience. Available online: https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1757-899X/1019/1/012057 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Swartz, M.M.; Byers, W.A.; Lojek, J.; Blunt, R. Westinghouse eVinciTM Heat Pipe Micro Reactor Technology Development. In International Conference on Nuclear Engineering; ICONE28-67519; American Society of Mechanical Engineers: New York City, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 85246, p. V001T04A018. 12p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Tian, Z.; Liu, J. Steady-State and Transient Analysis in Single-Phase Natural Circulation of ABV-6M. In Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Nuclear Engineering, Xi’an, China, 17–21 May 2010; ICONE18-30009. pp. 949–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Xie, J.; Deng, N.; Chen, P.; Wu, Z.; Yu, T. Effect of KLT-40S Fuel Assembly Design on Burnup Characteristics. Energies 2023, 16, 3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindley, B.A.; Kotlyar, D.; Parks, G.T.; Lillington, J.N.; Petrovic, B. Reactor Physics Modelling of Accident Tolerant Fuel for LWRs Using ANSWERS Codes. EPJ Nucl. Sci. Technol. 2016, 2, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squarer, D.; Schulenberg, T.; Struwe, D.; Oka, Y.; Bittermann, D.; Aksan, N.; Maraczy, C.; Kyrki-Rajamäki, R.; Souyri, A.; Dumaz, P. High Performance Light Water Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2003, 221, 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gougar, H.D.; Petti, D.A.; Demkowicz, P.A.; Windes, W.E.; Strydom, G.; Kinsey, J.C.; Ortensi, J.; Plummer, M.; Skerjanc, W.; Williamson, R.L.; et al. The US Department of Energy’s High Temperature Reactor Research and Development Program–Progress as of 2019. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2020, 358, 110397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Wu, F.; Ai, C.; Chen, C.; Wu, X.; Zhong, P.; Yan, J. Modeling and Analysis of Control Rod Drop in a Floating Nuclear Power Plant under Ocean Conditions. Ocean Eng. 2025, 338, 121992. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, P.; Read, N. On the Practicalities of Producing a Nuclear Weapon Using High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2025, 215, 111235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, S.H.; Lee, S.N.; Jo, C.K.; Kim, C.S. Conceptual Core Design and Neutronics Analysis for a Space Heat Pipe Reactor Using a Low Enriched Uranium Fuel. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2022, 387, 111603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hajipour, M.; Ansarifar, G.R.; Yeganeh, M.H.Z. Assessment and Predicting the Effect of Accident Tolerant Fuel Composition and Geometry on Neutronic and Safety Parameters in Small Modular Reactors via Artificial Neural Network and Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2025, 433, 113837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari-Jeyhouni, R.; Rezaei Ochbelagh, D.; Maiorino, J.R.; D’Auria, F.; de Stefani, G.L. The Utilization of Thorium in Small Modular Reactors—Part I: Neutronic Assessment. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2018, 120, 422–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amatullah, A.; Permana, S.; Irwanto, D.; Aimon, A.H. Comparative Analysis on Small Modular Reactor (SMR) with Uranium and Thorium Fuel Cycle. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 418, 112934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbari, R.; Aghili Nasr, M.; D’Auria, F.; Cammi, A.; Maiorino, J.R.; de Stefani, G.L. Analysis of Thorium-Transuranic Fuel Deployment in a LW-SMR: A Solution toward Sustainable Fuel Supply for the Future Plants. Nucl. Eng. Des. 2024, 421, 113090. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, M. Small Modular Reactors and the Future of Nuclear Power in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2014, 3, 161–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsige-Tamirat, H. Neutronics Assessment of the Use of Thorium Fuels in Current Pressurized Water Reactors. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2011, 53, 717–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwijayanto, R.A.P.; Miftasani, F.; Harto, A.W. Assessing the Benefit of Thorium Fuel in a Once through Molten Salt Reactor. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 176, 105369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ault, T.; Krahn, S.; Croff, A. Thorium Fuel Cycle Research and Literature: Trends and Insights from Eight Decades of Diverse Projects and Evolving Priorities. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2017, 110, 726–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, T.; Feng, B.; Heidet, F. Molten Salt Reactor Core Simulation with PROTEUS. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 140, 107099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldova, D.; Fridman, E.; Shwageraus, E. High Conversion Th–U233 Fuel for Current Generation of PWRs: Part II—3D Full Core Analysis. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2014, 73, 560–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayan, P.K.; Shivakumar, V.; Basu, S.; Sinha, R.K. Role of Thorium in the Indian Nuclear Power Programme. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2017, 101, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dawood, K.; Palmtag, S. METAL: Methodology for Liquid Metal Fast Reactor Core Economic Design and Fuel Loading Pattern Optimization. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 173, 105232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawford, D.C.; Porter, D.L. Applying U.S. Metal Fuel Experience to New Fuel Designs for Fast Reactors. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 171, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Genk, M.S.; Schriener, T.M. Post-Operation Radiological Source Term and Dose Rate Estimates for the Scalable LIquid Metal-Cooled Small Modular Reactor. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2018, 115, 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scientific Research and Community | Open Access Journals. Available online: https://www.onlinescientificresearch.com/journals/jmsmr/abstract/advanced-reactor-concept-arc-a-nuclear-energy-perspective-2040.html (accessed on 8 September 2025).

- Lee, S.W.; Lee, Y.; Kim, N.; Jo, H. Design of Heat Pipe Cooled Microreactor Based on Cycle Analysis and Evaluation of Applicability for Remote Regions. Energy Convers. Manag. 2023, 288, 117126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Chen, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhao, X.; Gao, Y.; Dinavahi, V. Small Modular Reactors: An Overview of Modeling, Control, Simulation, and Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 39628–39650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, D.H.; Hong, S.G. Neutronic Analysis on TRU Multi-Recycling in PWR-Based SMR Core Loaded with MOX (U-TRU) and FCM (TRU) Fueled Assemblies. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2022, 179, 109435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tosolin, A.; Beneš, O.; Colle, J.-Y.; Souček, P.; Luzzi, L.; Konings, R.J.M. Vaporization Behaviour of the Molten Salt Fast Reactor Fuel: The LiF-ThF4-UF4 System. J. Nucl. Mater. 2018, 508, 319–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schønfeldt, T.; Klinkby, E.; Schofield, A.V.; Pettersen, E.E.; Puente-Espel, F. Chapter 24-Seaborg Technologies ApS—Compact Molten Salt Reactor Power Barge. In Molten Salt Reactors and Thorium Energy, 2nd ed.; Dolan, T.J., Pázsit, I., Rykhlevskii, A., Yoshioka, R., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing Series in Energy; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2024; pp. 907–918. ISBN 978-0-323-99355-5. [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, V.; Branger, E.; Grape, S.; Elter, Z.; Mirmiran, S. Material Attractiveness of Irradiated Fuel Salts from the Seaborg Compact Molten Salt Reactor. Nucl. Eng. Technol. 2024, 56, 3969–3980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuler, S.P.; Webler, T. The Challenge of Community Acceptance of Small Nuclear Reactors. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 2024, 118, 103831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, M. Molten Salt Reactors: Current Technology Status and the Challenges for Maritime Applications. In Proceedings of the 17th International Naval Engineering Conference & Exhibition, Liverpool, UK, 5–7 November 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Stable Salt Reactor—A Radically Simpler Option for Use of Molten Salt Fuel | SpringerLink. Available online: https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-981-13-2658-5_37 (accessed on 14 July 2025).

- Bushnag, M.; Oh, T.; Kim, Y. A Neutronic Study on Safety Characteristics of Fast Spectrum Stable Salt Reactor (SSR). In Proceedings of the Challenges and Recent Advancements in Nuclear Energy Systems; Shams, A., Al-Athel, K., Tiselj, I., Pautz, A., Kwiatkowski, T., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 600–611. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, R.; Brown, N.R. Potential Fuel Cycle Performance of Floating Small Modular Light Water Reactors of Russian Origin. Ann. Nucl. Energy 2020, 144, 107555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, I.J.; Bang, I.C. The Time for Revolutionizing Small Modular Reactors: Cost Reduction Strategies from Innovations in Operation and Maintenance. Prog. Nucl. Energy 2024, 174, 105288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Zhang, B.; Su, K.; Li, Y.; Zhu, H.; Pan, H. A Preliminary Study of Digital Twin for Nuclear Reactor Dynamics: A Synergy of Machine Learning and Model Predictive Control. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 153, 110940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Alsafadi, F.; Mui, T.; O’Grady, D.; Hu, R. Development of Whole System Digital Twins for Advanced Reactors: Leveraging Graph Neural Networks and SAM Simulations. Nucl. Technol. 2025, 211, 2206–2223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Peng, S.; Deng, J.; Zeng, H.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, P. A Review of the Application of Artificial Intelligence to Nuclear Reactors: Where We Are and What’s Next. Heliyon 2023, 9, e13883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Insepov, Z.; Lesbayev, B.T.; Tanirbergenova, S.; Alsar, Z.; Kalybay, A.A.; Mansurov, Z.A. Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors as a Driver of Development of Nuclear Technologies. Energies 2025, 18, 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215766

Insepov Z, Lesbayev BT, Tanirbergenova S, Alsar Z, Kalybay AA, Mansurov ZA. Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors as a Driver of Development of Nuclear Technologies. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215766

Chicago/Turabian StyleInsepov, Zinetula, Bakhytzhan T. Lesbayev, Sandugash Tanirbergenova, Zhanna Alsar, Aisultan A. Kalybay, and Zulkhair A. Mansurov. 2025. "Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors as a Driver of Development of Nuclear Technologies" Energies 18, no. 21: 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215766

APA StyleInsepov, Z., Lesbayev, B. T., Tanirbergenova, S., Alsar, Z., Kalybay, A. A., & Mansurov, Z. A. (2025). Small Modular Nuclear Power Reactors as a Driver of Development of Nuclear Technologies. Energies, 18(21), 5766. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215766

_Insepov.png)