AutoML-Assisted Classification of Li-Ion Cell Chemistries from Cycle Life Data: A Scalable Framework for Second-Life Sorting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

2.1. Overview of the AutoML-Based Framework

2.2. Data Source and Selection

- SNL_18650_LFP_25C_0-100_0.5-1C_c_timeseries

- SNL_18650_NMC_25C_0-100_0.5-1C_b_timeseries

- SNL_18650_NCA_25C_0-100_0.5-1C_d_timeseries

3. Cycle-Level Data Analysis and Segmentation

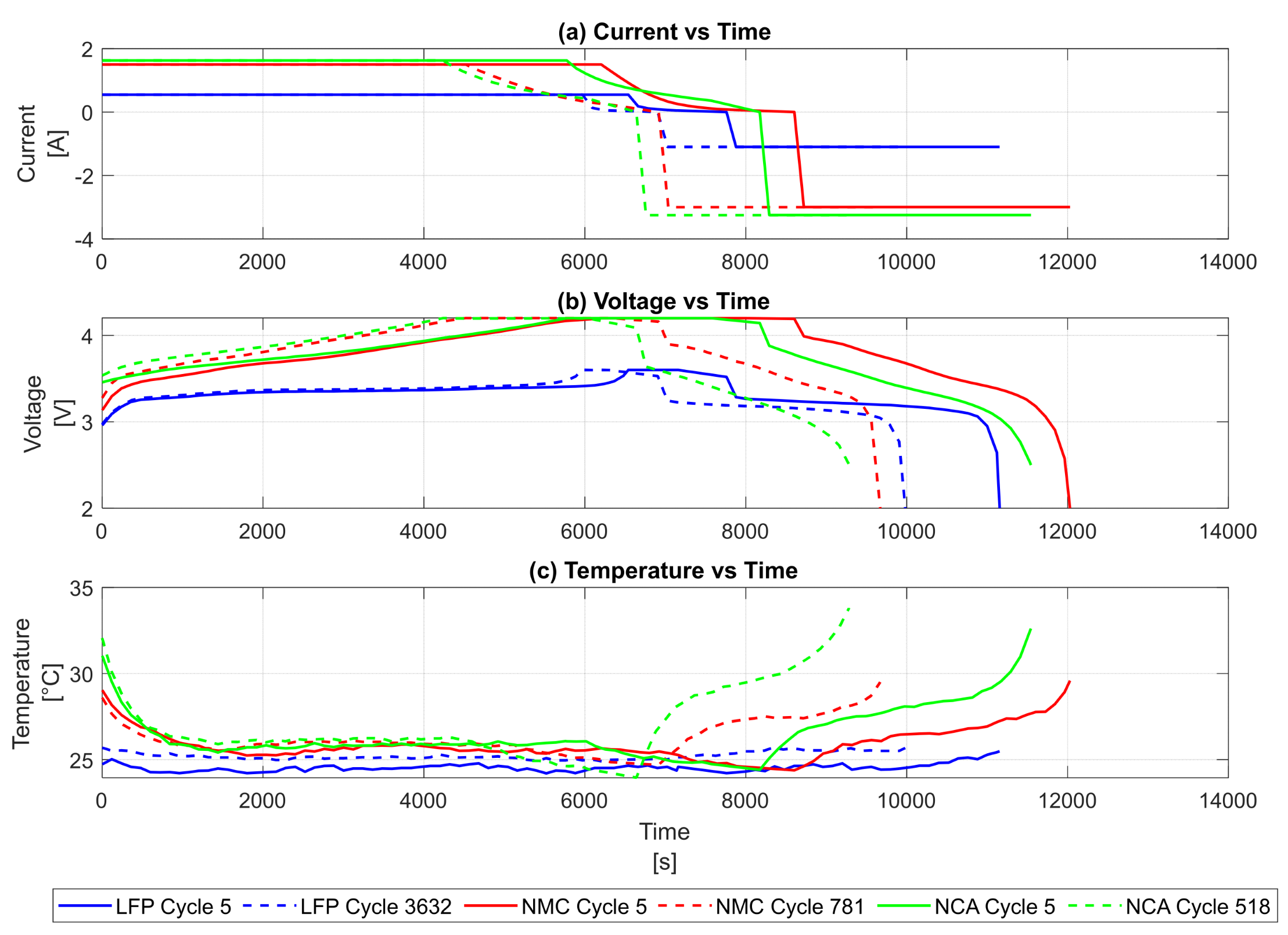

3.1. Time-Series Profiles of Cycle Life Across Chemistries

3.2. Cycle-Level Comparison of Early-Life and Late-Life Behaviour

3.2.1. Electrochemical Behaviour (Current & Voltage)

3.2.2. Thermal Behaviour

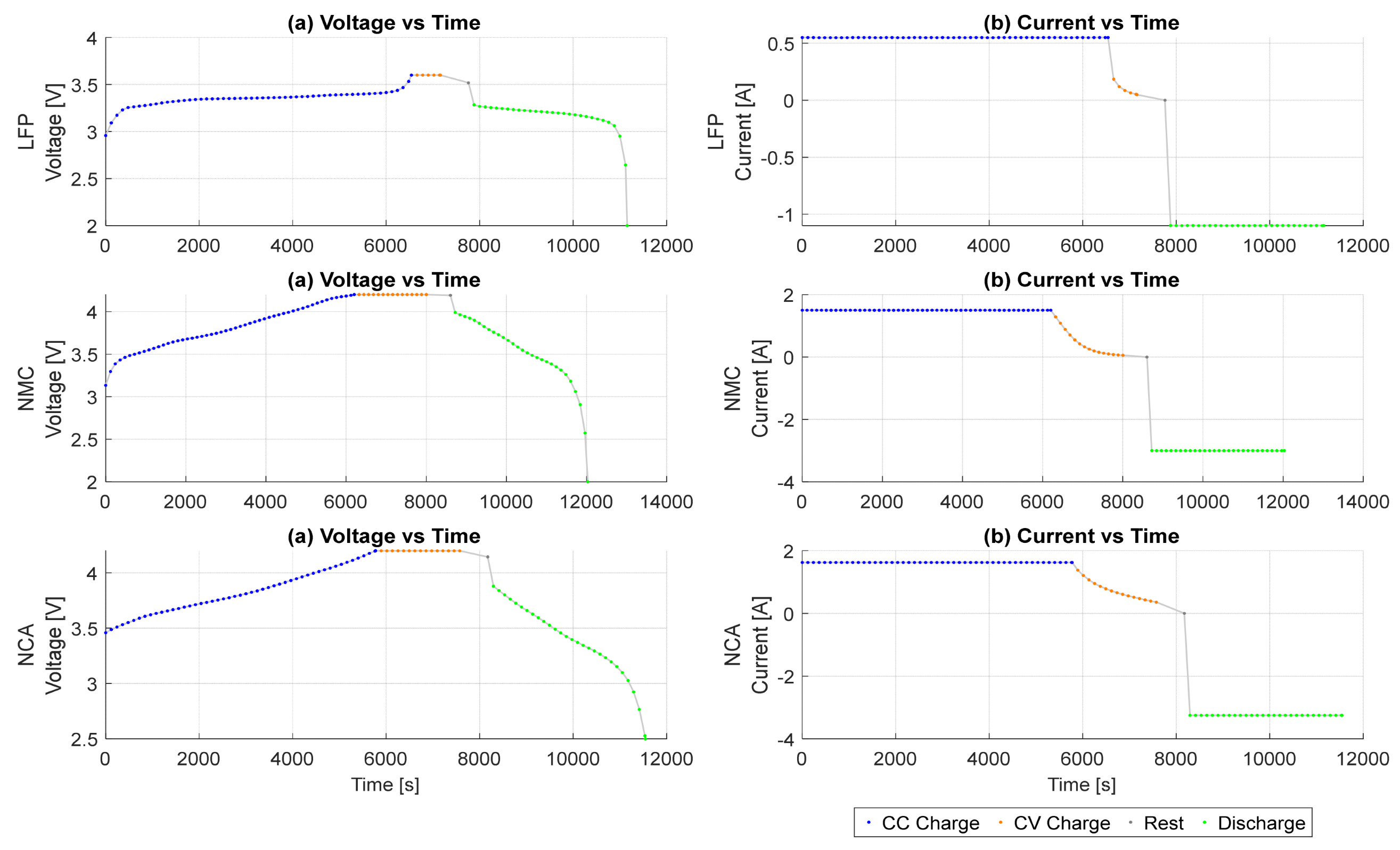

3.3. Analysis of Segmented Operational Phases

3.4. Cycle Exclusions and Scope Considerations

- Reference Performance Tests: These cycles, previously mentioned in Section 2.2, were periodically inserted to assess baseline performance and SoH. Although useful for benchmarking, RPTs exhibit behaviour that differs from standard cycling, particularly in voltage, current, and temperature profiles. To maintain consistency in feature extraction, they were manually identified and excluded based on known test schedules.

- Irregular or Anomalous Cycles: Cycles exhibiting unusual variations in capacity, voltage, or duration (often due to sensor dropout, protocol interruptions, or data corruption) were flagged and excluded. For example, cycles missing operational segments (e.g., absent CC or CV steps) were detected using the hDetectMissingStepCycles function, a diagnostic utility within MATLAB’s PMT [19].

- Abnormally Long-Time Intervals: Time-series data are expected to progress with consistent sampling intervals. However, extended gaps (e.g., >3600 s) between consecutive data points, typically caused by system auto-restarts, can distort temporal resolution. These anomalies were identified through time-difference analysis and visual inspection. Depending on severity, either the affected data points or entire cycles were excluded [19].

- Scope Limitation for Feature Extraction: Feature engineering and diagnostic analysis in Section 4 focus primarily on the CC charge phase. This decision reflects both practical and diagnostic considerations. While CC discharge data may also be suitable for machine learning, it was not explored in this study. Although the CV phase was excluded from ICA, DVA, and DTA diagnostics due to its flat voltage profile and limited dynamic behaviour, it was still included in the feature extraction process using MATLAB’s batteryTestFeatureExtractor. When the CV flag is enabled, the extractor computes several built-in statistical and segment-specific features from CV data. Despite operating at a higher C-rate than typically recommended, the CC charge phase remains suitable for ICA-based diagnostics, which benefit from lower noise and clearer electrochemical signatures.

4. Diagnostic Evaluation of Engineered Features

4.1. Diagnostic Curve Analysis

4.1.1. Incremental Capacity Curves Across Cycles

4.1.2. Differential Voltage Curves Across Cycles

4.1.3. Differential Thermal Curves Across Cycles

4.1.4. Annotated IC Curve Features for Cycle 5

4.2. Feature Grouping and Temporal Evolution

4.2.1. IC and Current-Derived Features

- (a)

- Charge_Step9_CC_energy: Shows a strong declining trend for NMC and NCA, indicating progressive capacity fade and reduced energy throughput during the current constant phase.

- (b)

- Charge_Step9_CC_duration: Exhibits a consistent downward trend for NMC and NCA, reflecting reduced charge acceptance time as cells age.

- (c)

- Charge_Step9_CCCV_energyRatio: Increases for LFP, suggesting a shift in energy delivery dynamics between CC and CV phases, while remaining stable for NMC and NCA.

- (d)

- Charge_Current_kurtosis: Captures changes in the shape of current distribution, with NMC and NCA showing evolving kurtosis values that may reflect ageing-induced variability in current profiles.

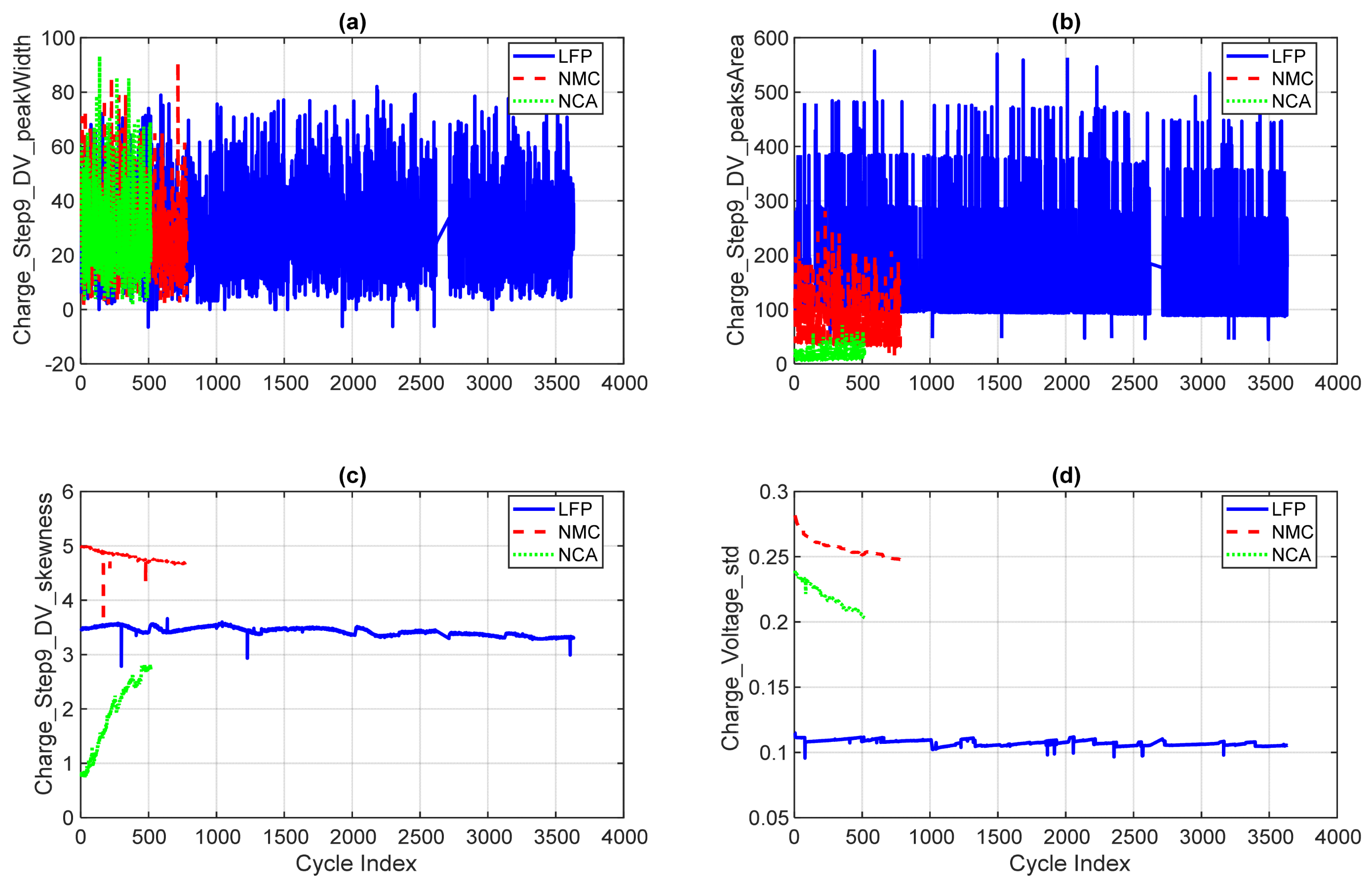

4.2.2. DV-Derived Voltage Features

- (a)

- Charge_Step9_DV_peakWidth: Although the subplot contains dense data points leading to visual overlap, the trends remain interpretable. LFP exhibits a relatively stable DV peak width across its long cycle life, with occasional fluctuations. In contrast, NMC and NCA show higher initial peak widths that decrease and stabilise within the early cycles, reflecting ageing-related changes in voltage transition complexity.

- (b)

- Charge_Step9_DV_peaksArea: Captures the cumulative area under all DV peaks during charging. NMC and NCA exhibit broader transitions and increased internal resistance, while LFP remains stable and narrow across cycles.

- (c)

- Charge_Step9_DV_skewness: Measures the asymmetry of voltage response. NMC starts with higher skewness and gradually declines, reflecting ageing-induced shifts in reaction kinetics. LFP remains near zero, while NCA shows minimal variation.

- (d)

- Charge_Voltage_std: A statistical descriptor of voltage variability during charging. NMC and NCA display higher standard deviation values, while LFP maintains a low and stable profile, reinforcing its electrochemical stability.

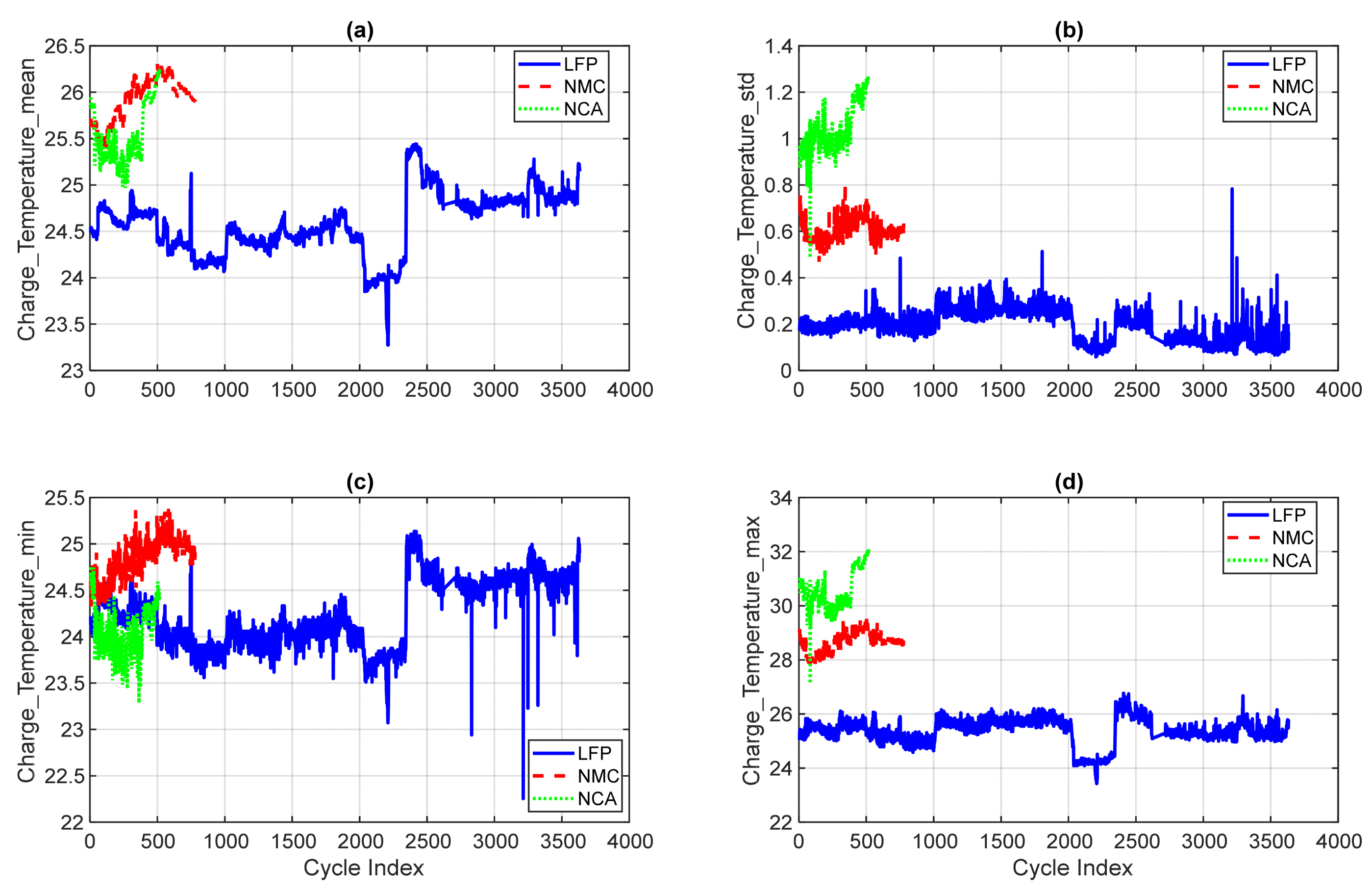

4.2.3. Statistical Temperature Features

- (a)

- Charge_Temperature_mean: LFP maintains a consistently low mean temperature profile, typically below 30 °C. NMC and NCA show elevated mean temperatures, with NCA reaching over 40 °C in late-life cycles, indicating higher internal resistance and thermal stress.

- (b)

- Charge_Temperature_std: Standard deviation values are lowest for LFP, reflecting thermal stability. NMC and NCA exhibit greater variability, with NCA showing the highest fluctuations.

- (c)

- Charge_Temperature_min: LFP consistently records the lowest minimum temperatures across cycles, often below 25 °C. NMC and NCA show slightly higher minimums, with occasional dips during rest phases.

- (d)

- Charge_Temperature_max: NCA reaches peak temperatures exceeding 45 °C in late-life cycles, while LFP remains below 35 °C.

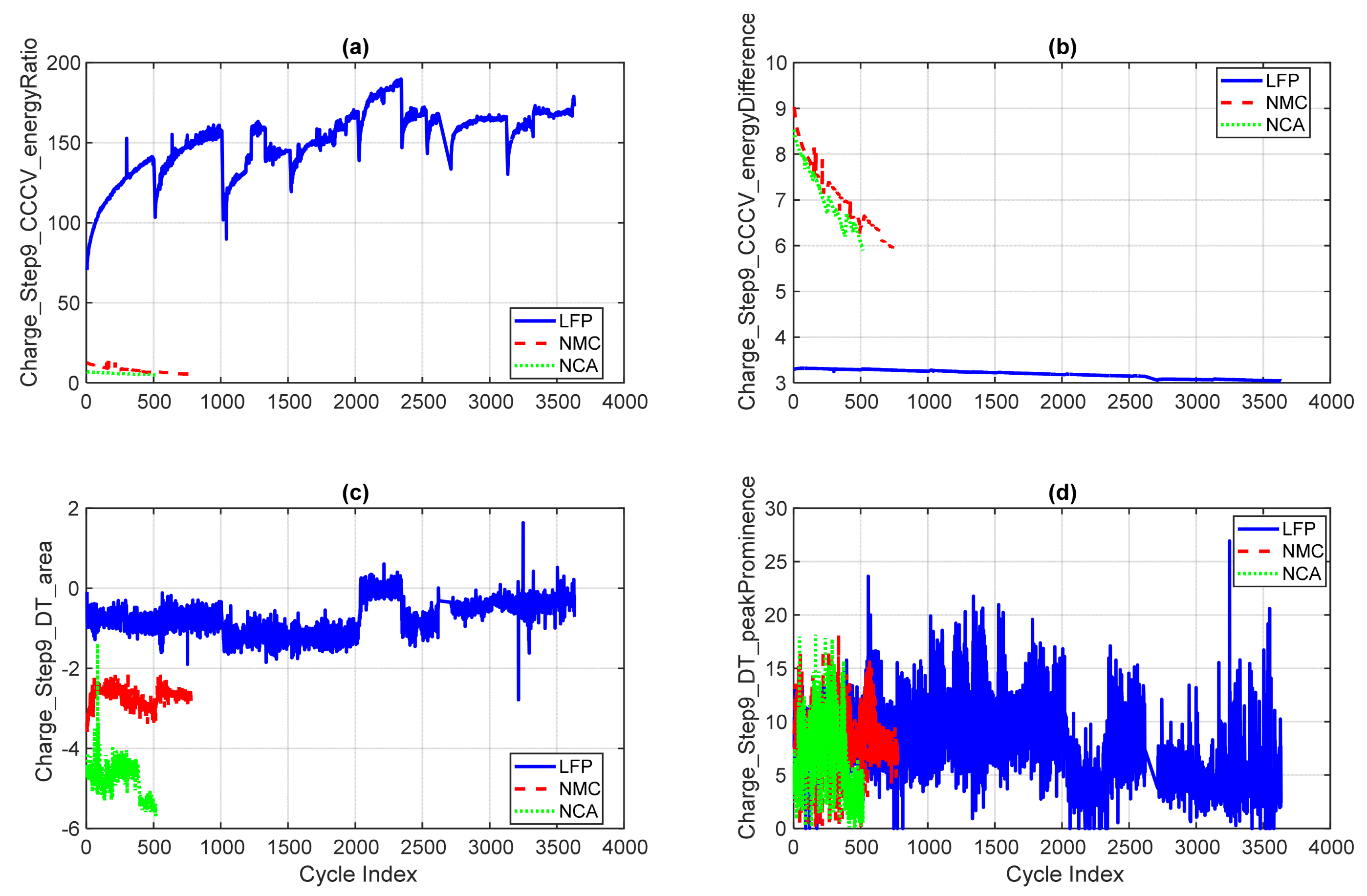

4.2.4. CV, DT, Segment, and Cycle-Level Metrics

- (a)

- Charge_Step9_CCCV_energyRatio: Reflects the relative energy delivered during the constant current (CC) and constant voltage (CV) phases. LFP shows a rising trend, indicating a shift in energy delivery dynamics, while NMC and NCA remain relatively stable.

- (b)

- Charge_Step9_CCCV_energyDifference: Measures the absolute energy difference between CC and CV phases. NMC and NCA exhibit declining trends, consistent with ageing-related reductions in CV energy throughput.

- (c)

- Charge_Step9_DT_area: Represents the total area under the differential thermal curve, capturing cumulative heat generation. NCA shows the highest values and variability, reflecting elevated internal resistance and thermal stress.

- (d)

- Charge_Step9_DT_peakProminence: Quantifies the strength of the dominant thermal peak. NCA displays prominent peaks, while LFP remains flat and stable, reinforcing its thermal resilience.

4.3. Feature Correlation Analysis

- Extracting common features from segmented charge–discharge cycles;

- Applying mean imputation to handle missing values;

- Calculating pairwise correlations using MATLAB’s corr function.

- Statistical descriptors (e.g., mean, standard deviation, skewness);

- Cycle-cumulative metrics (e.g., capacity, energy);

- Segment-specific indicators (e.g., CC/CV durations, slopes);

- Differential curve features (e.g., IC, DV, DT profiles).

- LFP: Loosely coupled features with high independence, ideal for degradation tracking and interpretability.

- NCA: Balanced interdependencies across feature groups, supporting flexible and generalisable classification.

- NMC: Strong clustering in thermal and CV-phase domains, requiring targeted feature selection to reduce complexity.

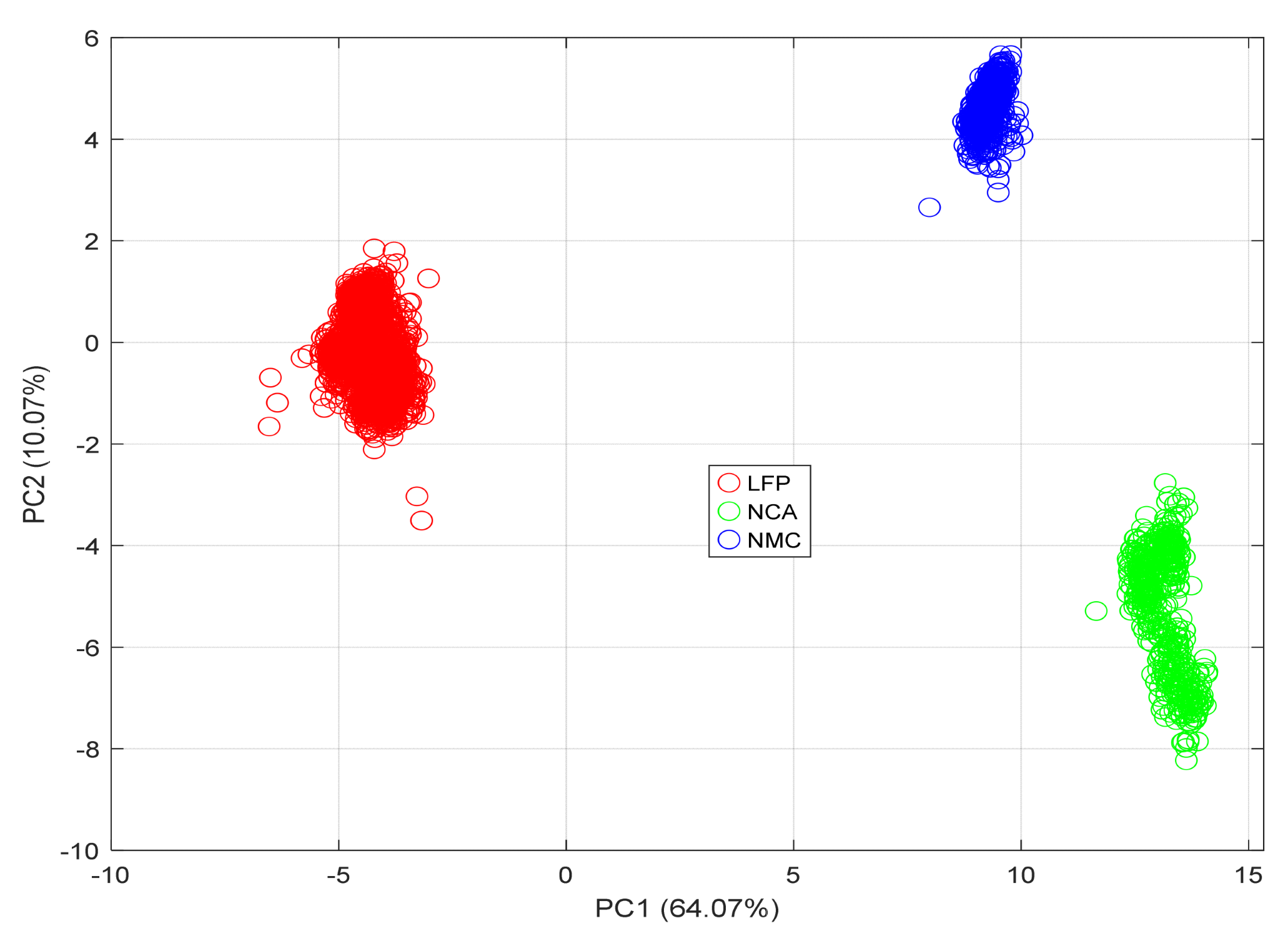

4.4. PCA-Based Feature Separability Analysis

- PC1 explains 64.07% of the variance.

- PC2 explains 10.07% of the variance.

- LFP samples form a distinct and compact group, consistent with their stable voltage profiles, narrow IC peaks, and low thermal variability.

- NCA samples occupy an intermediate region, bridging the characteristics of LFP and NMC. Their spread reflects moderate feature coupling and a balance between electrochemical complexity and thermal behaviour.

- NMC samples form a compact cluster with slight elongation along PC1, reflecting strong internal correlations among temperature and CV-phase features.

5. Automated Machine Learning

5.1. Data Pre-Processing

5.2. Data Cleaning

5.3. Data Splitting

5.4. Data Normalisation

5.5. Feature Selection

- Charge_Step9_CV_duration

- Charge_Step9_DT_peakLeftSlope

- Charge_Step9_DT_peakRightSlope

- Charge_Step9_DV_area

- Charge_duration

- The CV duration and overall charge duration capture differences in voltage plateau behaviour and charge acceptance, with LFP showing shorter, more stable durations and NMC/NCA exhibiting longer, more variable profiles.

- The thermal slope features (left and right of the DT peak) highlight chemistry-specific heat generation patterns, with NCA showing steep gradients due to elevated internal resistance, while LFP remains thermally stable.

- The DV area reflects the complexity of voltage transitions, distinguishing LFP’s narrow, stable response from the broader, evolving profiles of NMC and NCA.

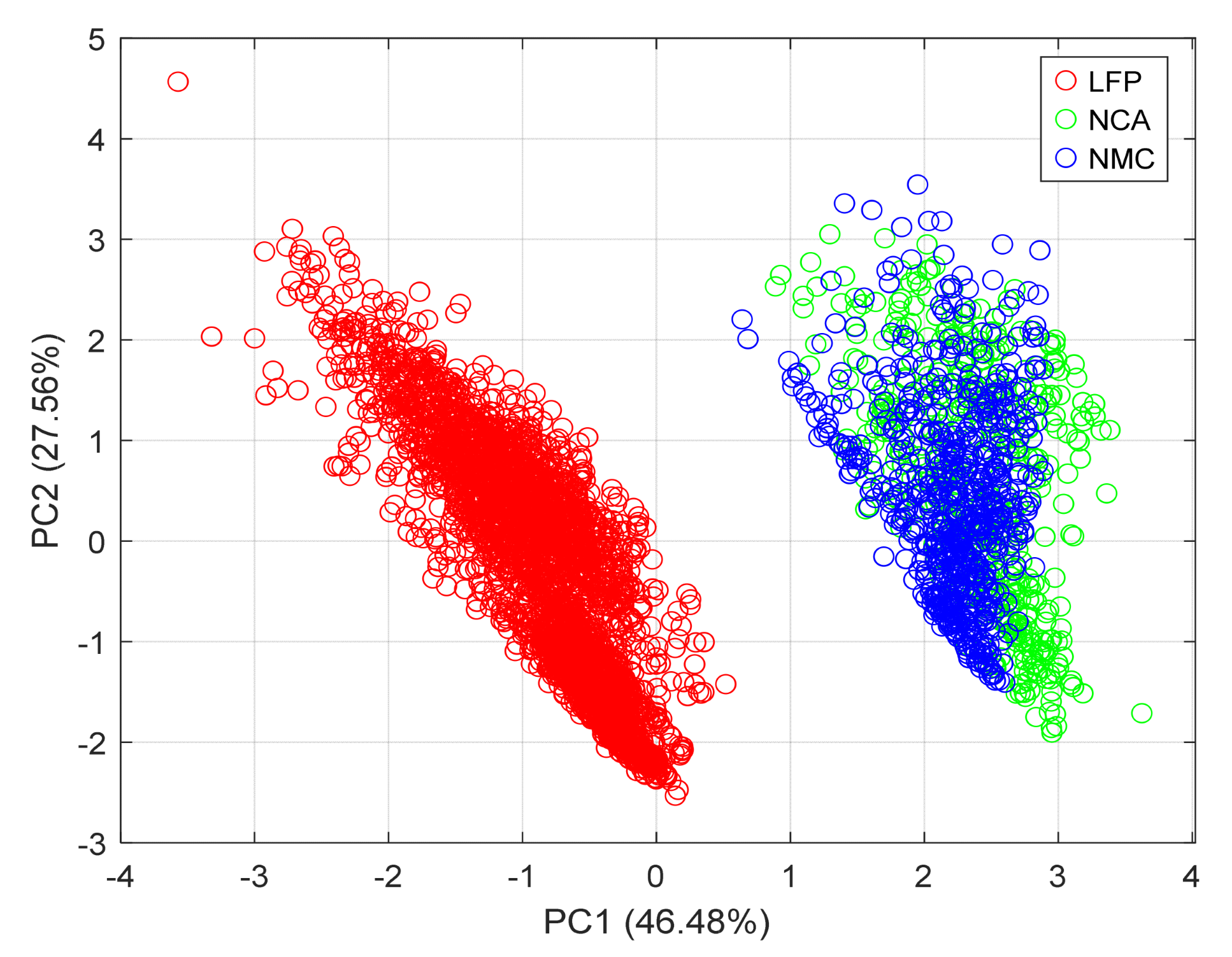

5.6. PCA-Based Assessment of SFS-Optimised Features

6. Results and Discussion

6.1. AutoML Model Optimisation

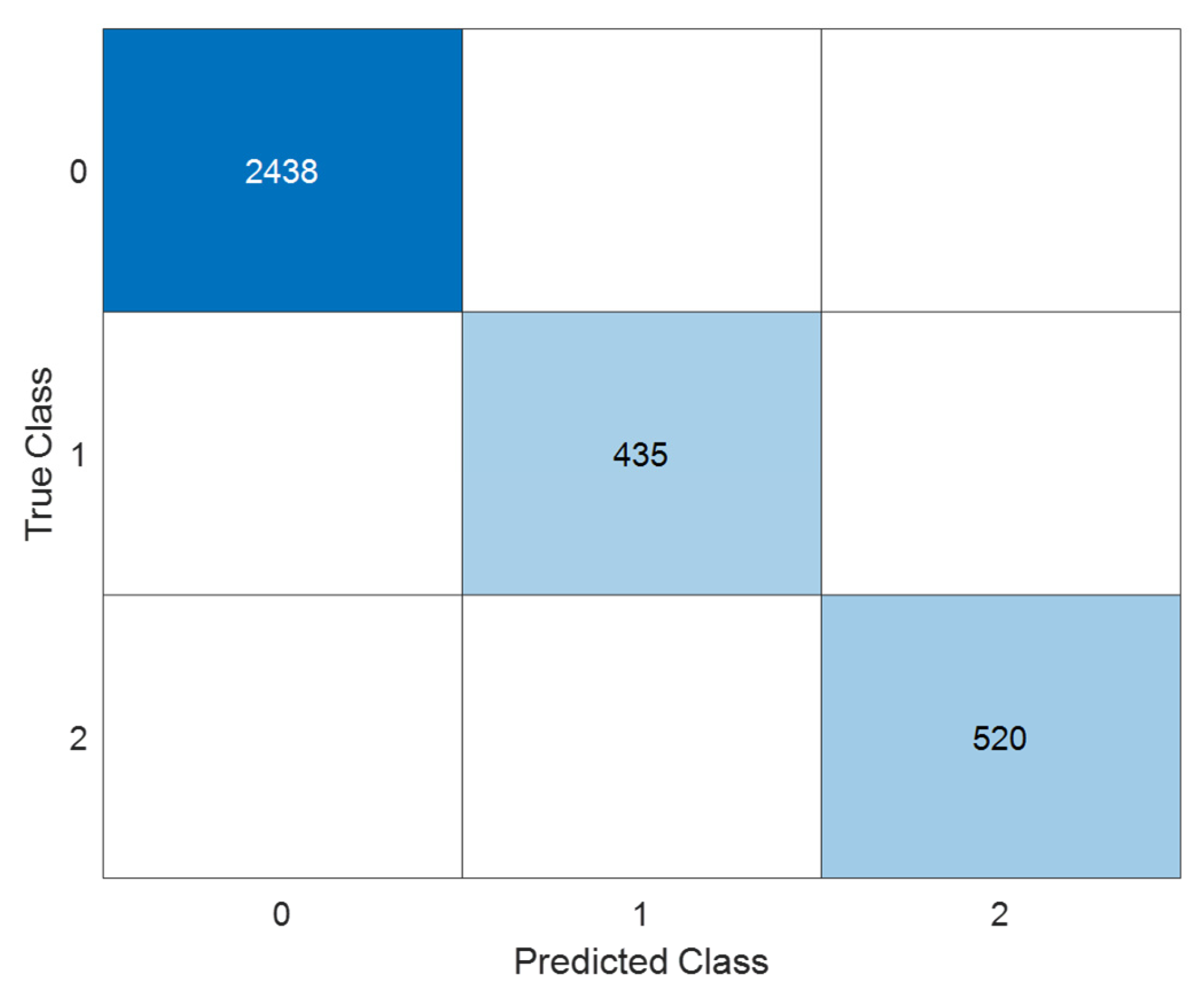

6.2. Classification Performance: Confusion Matrix Analysis

6.2.1. Training Set

6.2.2. Test Set

- LFP (class 0): Out of 1045 samples, all were correctly classified (100% recall and precision), indicating excellent robustness in identifying this chemistry type.

- NCA (class 1): All 186 instances were accurately predicted, again yielding perfect recall and precision for this class. This is particularly notable given that NCA can sometimes exhibit overlapping electrochemical features with NMC in raw data.

- NMC (class 2): Of the 223 NMC samples, 222 were correctly classified, with only one instance misclassified as NCA. This represents a misclassification rate of less than 0.45%, which is negligible but could suggest minor feature overlap or class imbalance in edge cases.

6.3. Limitations and Future Work

- Feature Engineering and Validation: The current feature set, although comprehensive, could be further improved by applying more constrained feature engineering and rigorous validation to ensure that only the most physically meaningful and robust features are used for classification.

- Short-Duration Measurement Data: The present study focuses on long-term cycling data. Adapting the framework to enable accurate classification using short-duration or partial cycling measurements would greatly enhance its applicability for rapid diagnostics and industrial workflows.

- Cyclability Assumption and Non-Cycling Diagnostics: The current framework assumes that cells are cyclable to some extent, enabling feature extraction from charge–discharge data. In practical second-life workflows, most candidate cells undergo pre-screening to exclude non-functional or severely degraded units before diagnostic testing. However, this assumption limits applicability to only partially functional cells. Future work could extend the framework to incorporate non-cycling diagnostic methods, such as impedance spectroscopy or rest-phase voltage analysis, to enable classification of cells that cannot be cycled.

- Diverse Operating Conditions: The model was trained and validated on research-grade datasets under controlled conditions. Future work should focus on improving model classification accuracy under a wider range of operating conditions, including varying temperatures, cycling rates, and real-world industrial datasets.

- Degradation Mode Classification: While this work addresses chemistry classification, extending the approach to also classify cell degradation modes would provide valuable insights for second-life assessment and predictive maintenance.

- Generalisation to Out-of-Distribution Scenarios: Although the proposed framework demonstrates high classification accuracy across three chemistries under standardised cycling conditions, its performance under out-of-distribution (OOD) scenarios, such as different form factors, manufacturers, or degradation trajectories, remains to be evaluated. Future work will focus on validating the model using diverse datasets that reflect real-world variability in second-life and recycling contexts. This will help assess the robustness and generalisation capability of the framework beyond the current scope.

- Beyond technical performance: The proposed framework contributes to sustainable battery lifecycle management. By enabling accurate chemistry classification without reliance on manufacturer metadata, it supports rapid second-life qualification, safe module matching, and efficient recycling pretreatment. These capabilities align with circular economy principles and help reduce electrochemical waste in large-scale battery deployment.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3D | Three-dimensional |

| AutoML | Automated Machine Learning |

| CASH | Combined Algorithm Selection and Hyperparameter optimisation |

| CC | Constant Current |

| CCCV | Constant Current Constant Voltage |

| CV | Constant Voltage |

| DTA | Differential Thermal Analysis |

| DV | Differential Voltage |

| DVA | Differential Voltage Analysis |

| DoD | depth of discharge |

| ECOC | Error-Correcting Output Codes |

| EVs | electric vehicles |

| IC | Incremental Capacity |

| ICA | Incremental Capacity Analysis |

| KNN | K-Nearest Neighbours |

| LFP | Lithium Iron Phosphate |

| NCA | Nickel Cobalt Aluminium Oxide |

| NMC | Nickel Manganese Cobalt Oxide |

| OCV | open-circuit voltage |

| PCA | Principal Component Analysis |

| PMT | Predictive Maintenance Toolbox |

| RPT | Reference Performance Test |

| SFS | Sequential Forward Selection |

| SVM | Support Vector Machine |

| SoH | State of Health |

Appendix A. Diagnostic Feature Grouping and Definitions

- Incremental Capacity Analysis (ICA)

- Differential Voltage Analysis (DVA)

- Differential Thermal Analysis (DTA)

- Combined Segment-Level and Cycle-Level Metrics

| Feature Category | Feature Names |

|---|---|

| IC and Current Metrics (20 features) | Charge_Current_max, Charge_Current_min, Charge_Current_mean, Charge_Current_std, Charge_Current_skewness, Charge_Current_kurtosis, Charge_Step9_IC_peak, Charge_Step9_IC_peakWidth, Charge_Step9_IC_peakLocation, Charge_Step9_IC_peakProminence, Charge_Step9_IC_peaksArea, Charge_Step9_IC_peakLeftSlope, Charge_Step9_IC_peakRightSlope, Charge_Step9_IC_area, Charge_Step9_IC_max, Charge_Step9_IC_min, Charge_Step9_IC_mean, Charge_Step9_IC_std, Charge_Step9_IC_skewness, Charge_Step9_IC_kurtosis |

| DV Metrics (20 features) | Charge_Voltage_max, Charge_Voltage_min, Charge_Voltage_mean, Charge_Voltage_std, Charge_Voltage_skewness, Charge_Voltage_kurtosis, Charge_Step9_DV_peak, Charge_Step9_DV_peakWidth, Charge_Step9_DV_peakLocation, Charge_Step9_DV_peakProminence, Charge_Step9_DV_peaksArea, Charge_Step9_DV_peakLeftSlope, Charge_Step9_DV_peakRightSlope, Charge_Step9_DV_area, Charge_Step9_DV_max, Charge_Step9_DV_min, Charge_Step9_DV_mean, Charge_Step9_DV_std, Charge_Step9_DV_skewness, Charge_Step9_DV_kurtosisCharge_Voltage_max, Charge_Voltage_min, Charge_Voltage_mean, Charge_Voltage_std, Charge_Voltage_skewness, Charge_Voltage_kurtosis |

| Temperature Metrics (4 features) | Charge_Temperature_max, Charge_Temperature_min, Charge_Temperature_mean, Charge_Temperature_std |

| CV, DT, Segment, and Cycle-Level Metrics (31 features) | Charge_Step9_CV_duration, Charge_Step9_CV_energy, Charge_Step9_CV_kurtosis, Charge_Step9_CV_skewness, Charge_Step9_CV_slope, Charge_Step9_CV_voltageMedian, Charge_Step9_DT_area, Charge_Step9_DT_kurtosis, Charge_Step9_DT_max, Charge_Step9_DT_mean, Charge_Step9_DT_min, Charge_Step9_DT_peak, Charge_Step9_DT_peakLeftSlope, Charge_Step9_DT_peakLocation, Charge_Step9_DT_peakProminence, Charge_Step9_DT_peakRightSlope, Charge_Step9_DT_peakWidth, Charge_Step9_DT_peaksArea, Charge_Step9_DT_skewness, Charge_Step9_DT_std, Charge_Step9_CC_duration, Charge_Step9_CC_currentMedian, Charge_Step9_CC_energy, Charge_Step9_CC_skewness, Charge_Step9_CC_kurtosis, Charge_Step9_CCCV_energyRatio, Charge_Step9_CCCV_energyDifference, Charge_cumulativeCapacity, Charge_cumulativeEnergy, Charge_duration, Charge_startVoltage |

References

- IEA. Global EV Outlook; IEA: Paris, France, 2024; Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/global-ev-outlook-2024 (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Harper, G.; Sommerville, R.; Kendrick, E.; Driscoll, L.; Slater, P.; Stolkin, R.; Walton, A.; Christensen, P.; Heidrich, O.; Lambert, S.; et al. Recycling Lithium-Ion Batteries from Electric Vehicles. Nature 2019, 575, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez-Laserna, E.; Sarasketa-Zabala, E.; Villarreal Sarria, I.; Stroe, D.I.; Swierczynski, M.; Warnecke, A.; Timmermans, J.M.; Goutam, S.; Omar, N.; Rodriguez, P. Technical Viability of Battery Second Life: A Study from the Ageing Perspective. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2018, 54, 2703–2713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berecibar, M.; Gandiaga, I.; Villarreal, I.; Omar, N.; Van Mierlo, J.; Van Den Bossche, P. Critical Review of State of Health Estimation Methods of Li-Ion Batteries for Real Applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2016, 56, 572–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meddings, N.; Heinrich, M.; Overney, F.; Lee, J.S.; Ruiz, V.; Napolitano, E.; Seitz, S.; Hinds, G.; Raccichini, R.; Gaberšček, M.; et al. Application of Electrochemical Impedance Spectroscopy to Commercial Li-Ion Cells: A Review. J. Power Sources 2020, 480, 228742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, W.; Hu, E.; Yan, Q.; Xiang, C.; Tseng, K.J.; Niyato, D. BatSort: Enhanced Battery Classification with Transfer Learning for Battery Sorting and Recycling. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Annual Congress on Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT), Melbourne, Australia, 24–26 July 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, N.; Cohen, T.; Alamdari, S.; Hsu, C.-W.; Williamson, G.; Beck, D.; Holmberg, V. DiffCapAnalyzer: A Python Package for Quantitative Analysis of Total Differential Capacity Data. J. Open Source Softw. 2020, 5, 2624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neubauer, J.; Smith, K.; Wood, E.; Pesaran, A. Identifying and Overcoming Critical Barriers to Widespread Second Use of PEV Batteries; National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL): Golden, CO, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lucaferri, V.; Quercio, M.; Laudani, A.; Riganti Fulginei, F. A Review on Battery Model-Based and Data-Driven Methods for Battery Management Systems. Energies 2023, 16, 7807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odinsen, E.; Amiri, M.N.; Burheim, O.S.; Lamb, J.J. Estimation of Differential Capacity in Lithium-Ion Batteries Using Machine Learning Approaches. Energies 2024, 17, 4954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amuta, O.; Yao, J.; Droese, D.; Kowal, J. Accurate Chemistry Identification of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on Temperature Dynamics with Machine Learning. Batteries 2025, 11, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karaoğlu, G.; Ulgut, B. Battery Chemistry Prediction with Short Measurements and a Decision Tree Algorithm: Sorting for a Proper Recycling Process. J. Energy Storage 2023, 72, 108232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wett, C.; Lampe, J.; Görick, D.; Seeger, T.; Turan, B. Identification of Cell Chemistries in Lithium-Ion Batteries: Improving the Assessment for Recycling and Second-Life. Energy AI 2025, 19, 100468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preger, Y.; Barkholtz, H.M.; Fresquez, A.; Campbell, D.L.; Juba, B.W.; Romàn-Kustas, J.; Ferreira, S.R.; Chalamala, B. Degradation of Commercial Lithium-Ion Cells as a Function of Chemistry and Cycling Conditions. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2020, 167, 120532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkholtz, H.M.; Fresquez, A.; Chalamala, B.R.; Ferreira, S.R. A Database for Comparative Electrochemical Performance of Commercial 18650-Format Lithium-Ion Cells. J. Electrochem. Soc. 2017, 164, A2697–A2706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.; Peng, Q.; Che, Y.; Zheng, Y.; Li, K.; Teodorescu, R.; Widanage, D.; Barai, A. Transfer Learning for Battery Smarter State Estimation and Ageing Prognostics: Recent Progress, Challenges, and Prospects. Adv. Appl. Energy 2023, 9, 100117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- BatteryArchive.Org. Available online: https://www.batteryarchive.org/study_summaries.html (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Data Analysis and Feature Extraction for Battery Raw Cycling Data—MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://uk.mathworks.com/help/predmaint/ug/data-analysis-and-feature-extraction-for-battery-raw-cycling-data.html (accessed on 6 September 2025).

- Luo, C.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, D.; Lai, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, S. Life Prediction under Charging Process of Lithium-Ion Batteries Based on AutoML. Energies 2022, 15, 4594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbudo, R.; Ventura, S.; Romero, J.R. Eight Years of AutoML: Categorisation, Review and Trends. Knowl. Inf. Syst. 2023, 65, 5097–5149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Zhao, K.; Chu, X. AutoML: A Survey of the State-of-the-Art. Knowl. Based Syst. 2021, 212, 106622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santu, S.K.K.; Hassan, M.M.; Smith, M.J.; Xu, L.; Zhai, C.; Veeramachaneni, K. AutoML to Date and Beyond: Challenges and Opportunities. ACM Comput. Surv. 2022, 54, 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- AutoML Explained. Automated Machine Learning—MATLAB & Simulink. Available online: https://uk.mathworks.com/discovery/automl.html (accessed on 22 September 2025).

- Friedman, L.; Komogortsev, O.V. Assessment of the Effectiveness of Seven Biometric Feature Normalization Techniques. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2019, 14, 2528–2536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Kaur, A.; Singh, P.; Driss, M.; Boulila, W. Efficient Multiclass Classification Using Feature Selection in High-Dimensional Datasets. Electronics 2023, 12, 2290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chotchantarakun, K. Optimizing Sequential Forward Selection on Classification Using Genetic Algorithm. Informatica 2023, 47, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | LFP | NMC | NCA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nominal Capacity [Ah] | 1.1 | 3.0 | 3.2 |

| Current Behaviour | Low magnitude, stable | Fluctuating, high-energy density | Fluctuating, high-energy density |

| Voltage Behaviour [V] | Narrow, stable (~3.2–3.6) | Broad (~2.5–4.2) | Broad, highest (~2.5–4.2) |

| Thermal Response | Stable, low heat | Moderate | High, elevated resistance |

| Chemistry | Voltage Evolution | Current Profile | Phase Transition Clarity | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LFP | Rises from ~2.5 V to ~3.6 V; sharp drop during discharge | ~0.5 A; zero during CV/rest; negative during discharge | Smooth and stable | Reflects low-capacity, thermally resilient behaviour |

| NMC | Rises from ~2.5 V to ~4.2 V; short rest plateau; sharp discharge drop | ~2 A; clear CC charge → CV charge → rest → discharge transitions | Pronounced and well-defined | Indicates high energy density and complex dynamics |

| NCA | Similar to NMC; peaks at ~4.2 V | ~2 A; well-defined transitions | Clear and consistent | Elevated thermal response due to high voltage/current |

| Chemistry | Excluded Cycles |

|---|---|

| LFP | 1–4, 503–506, 508–511, 1010–1017, 1044, 1050, 1516–1523, 2022–2029, 2344–2347, 2529, 2530–2536, 2622, 2623, 2712, 3126–3134, 3633–3636 |

| NMC | 1–4, 253–256, 258–261, 386–393, 484, 518–525, 650–657, 782–785 |

| NCA | 1–4, 254–257, 259–262, 274, 314, 316, 387–394, 405, 446, 519–522 |

| Chemistry | IC Curve Characteristics | DV Curve Characteristics | DT Curve Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| LFP | Sharp, narrow peak near 3.4 V; stable across cycles | Single sharp peak near 3.4 V; narrow width | Flat and stable; minimal heat generation |

| NMC | Broad, complex peaks between 3.6–4.1 V; overlapping transitions | Multiple overlapping peaks around 3.7–4.1 V | Moderate thermal gradients; peaks near 3.8–4.1 V |

| NCA | Sharp transitions; prominent peak near 3.8–4.2 V | Sharper transitions than NMC; high peak slopes | Highest thermal sensitivity; sharp peaks near 4.2 V |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Parambu, R.B.K.; Farrag, M.E.; Gowaid, I.A.; Ibem, C.N. AutoML-Assisted Classification of Li-Ion Cell Chemistries from Cycle Life Data: A Scalable Framework for Second-Life Sorting. Energies 2025, 18, 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215738

Parambu RBK, Farrag ME, Gowaid IA, Ibem CN. AutoML-Assisted Classification of Li-Ion Cell Chemistries from Cycle Life Data: A Scalable Framework for Second-Life Sorting. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215738

Chicago/Turabian StyleParambu, Raees B. K., Mohamed E. Farrag, I. A. Gowaid, and Chukwuemeka N. Ibem. 2025. "AutoML-Assisted Classification of Li-Ion Cell Chemistries from Cycle Life Data: A Scalable Framework for Second-Life Sorting" Energies 18, no. 21: 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215738

APA StyleParambu, R. B. K., Farrag, M. E., Gowaid, I. A., & Ibem, C. N. (2025). AutoML-Assisted Classification of Li-Ion Cell Chemistries from Cycle Life Data: A Scalable Framework for Second-Life Sorting. Energies, 18(21), 5738. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215738