Performance Enhancement of a Novel Compression/Ejection Trans-Critical CO2 Heat Pump System Coupled with Composite Heat Sources

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Numerical Model

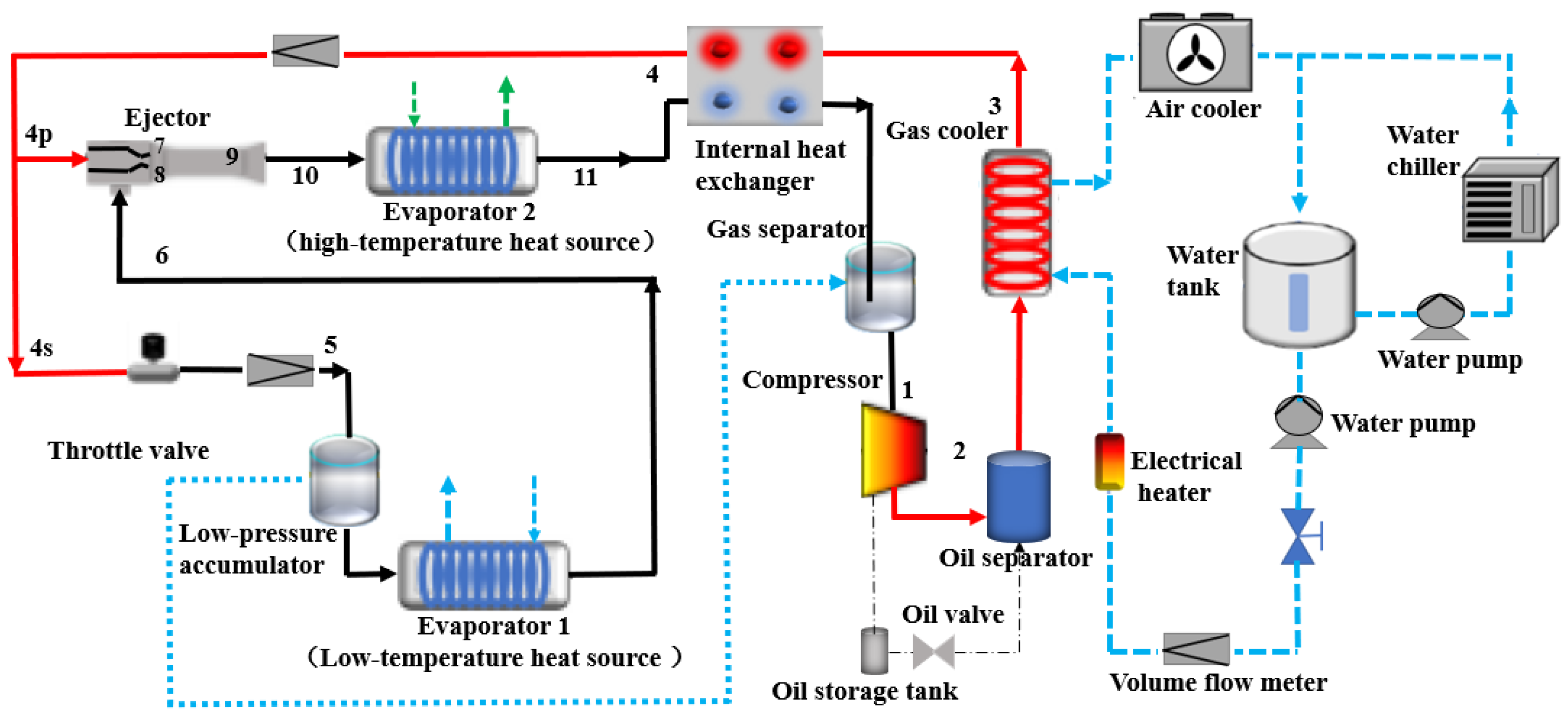

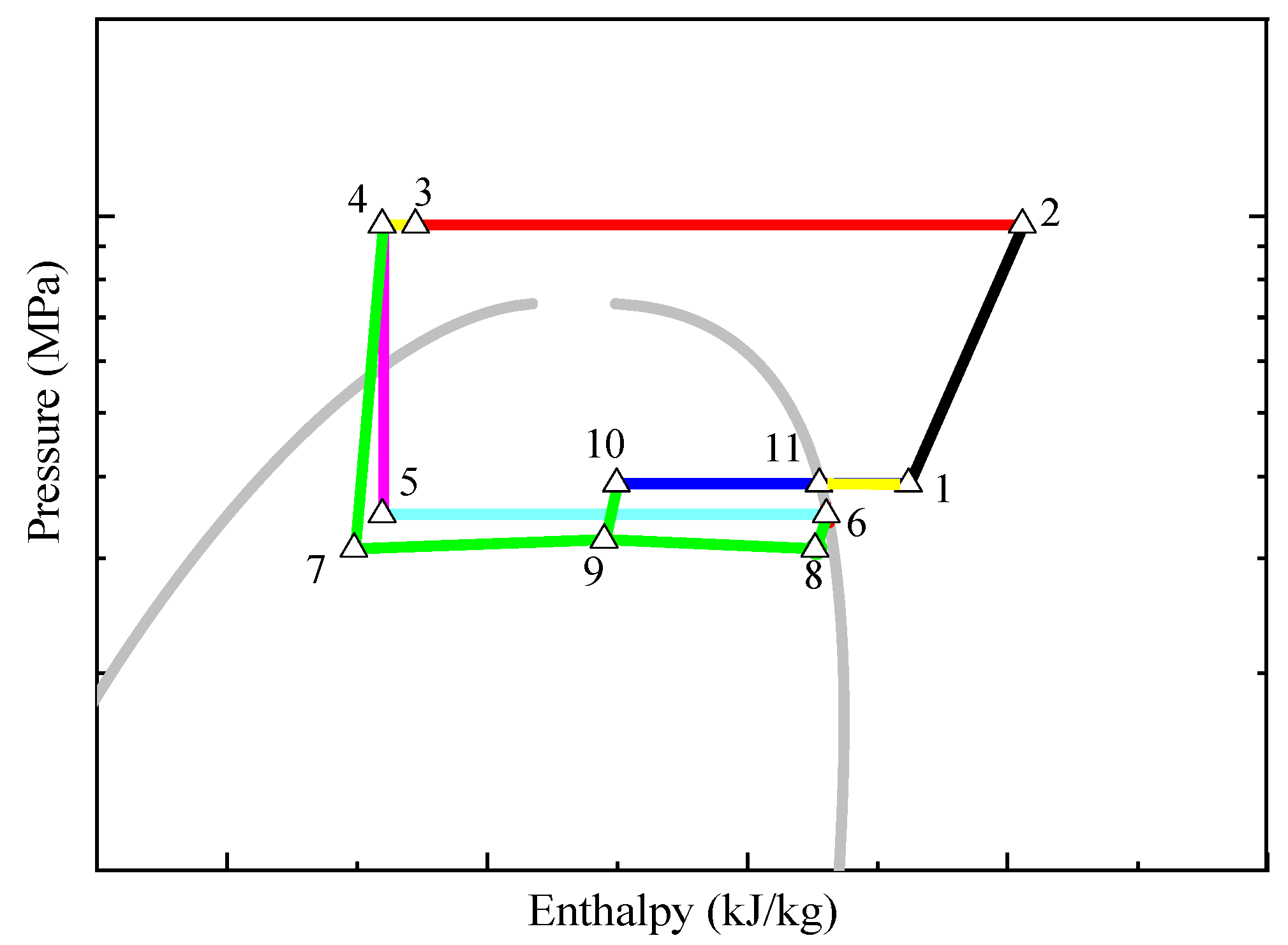

2.1. System Description

2.2. Mathematical Modeling and Simulation

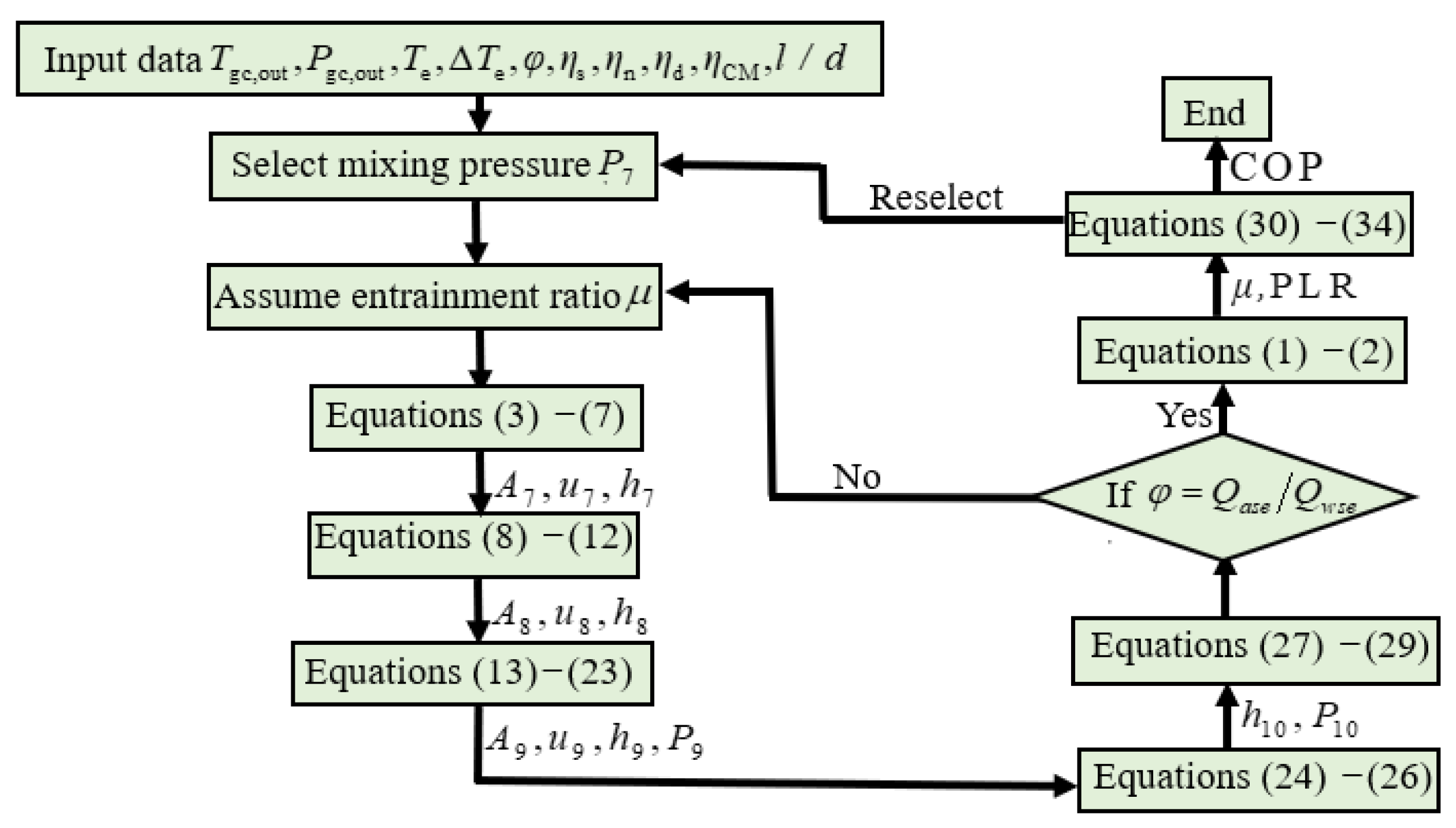

- (1)

- The parameters of state 7 can be calculated by Equations (3)–(7), and the parameters of state 8 can be obtained by Equations (8)–(12). Then, the mixing chamber outlet state 9 can be calculated from Equations (13)–(23). According to Equations (24)–(26), state 10 of the diffuser outlet state can be obtained.

- (2)

- According to Equations (27)–(29), the cooling capacity of the heat pump and the utilization ratio of the composite heat source are calculated, and whether the matching ratio of the composite heat source is the same as the input value is checked. If they are different, the ejector entrainment coefficient is reselected for calculation until the convergence error is satisfied.

- (3)

- The compressor power consumption, mass flow rate, and performance coefficient of the CTHP system can be calculated using Equations (30)–(34). The optimum mixing pressure under different working conditions is obtained.

- (4)

- The optimum system performance coefficient and corresponding Popt,out,gc are found using the same optimization. To achieve the optimum system performance, the results under the optimum mixing pressure corresponding to different Te are adopted. In this numerical model, the convergence errors of density and matching ratio of the composite heat source are both 10−3.

- (5)

- The maximum COP of the system was obtained by changing the outlet pressure of the gas cooler, and the step size was 1 kPa. For CTHP systems, the system COP can be expressed as .

2.3. Sensitivity Analysis of Ejector Efficiency

3. Experimental Setup and Model Verification

3.1. Experimental System

3.2. Test Procedure

3.3. Model Verification

4. Results and Discussion

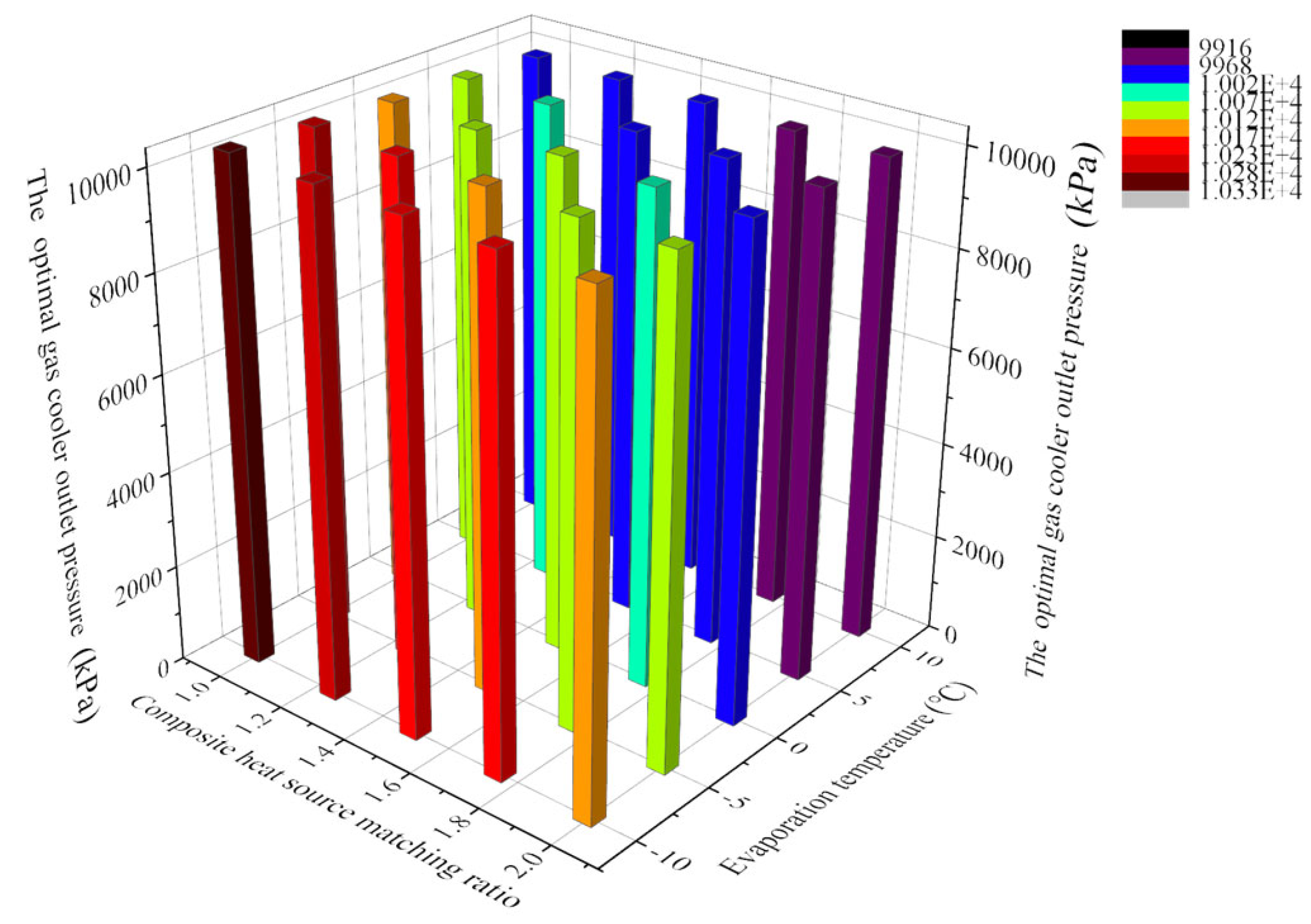

4.1. Gas Cooler Outlet Pressure

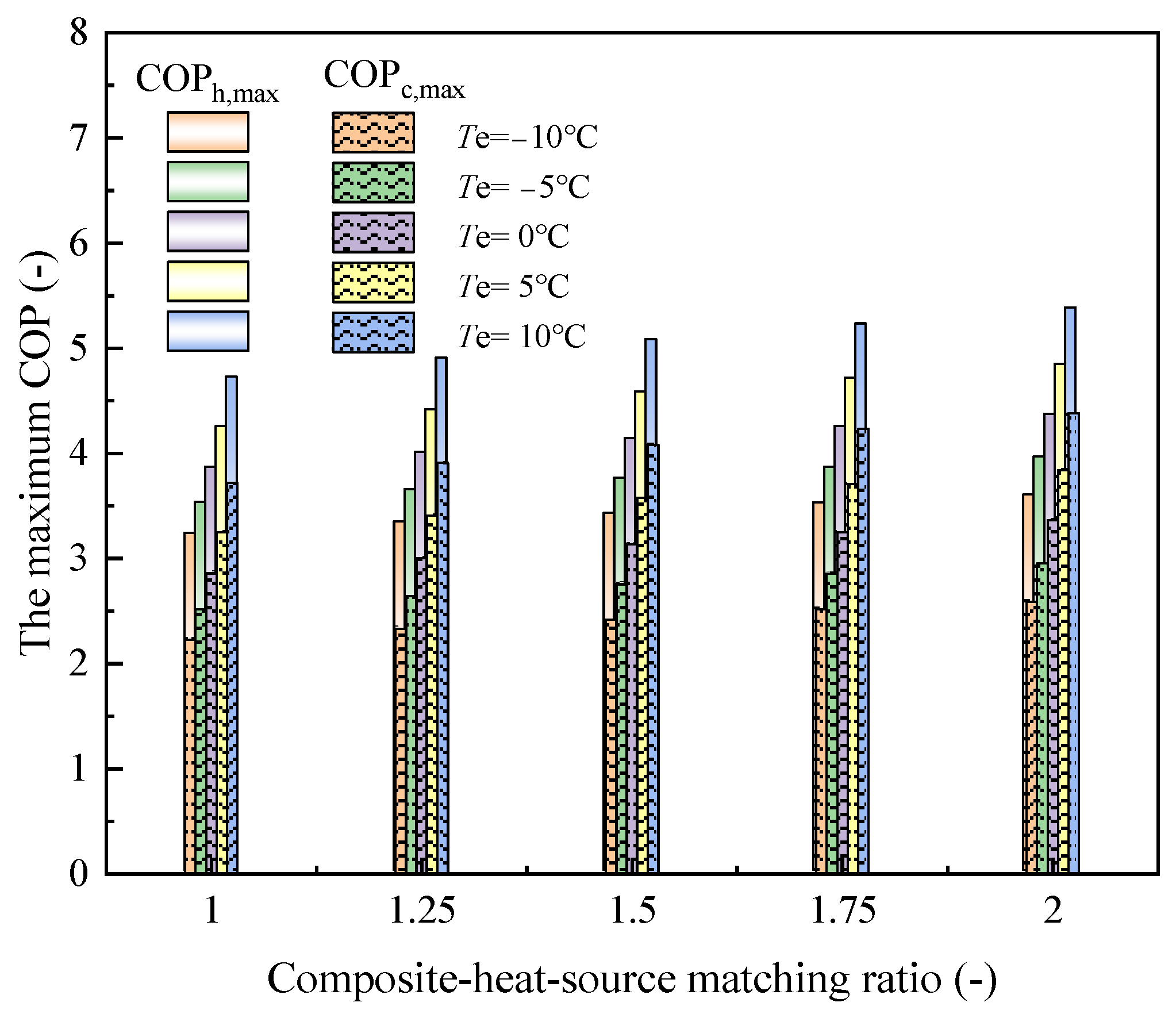

4.2. System Performance Coefficient

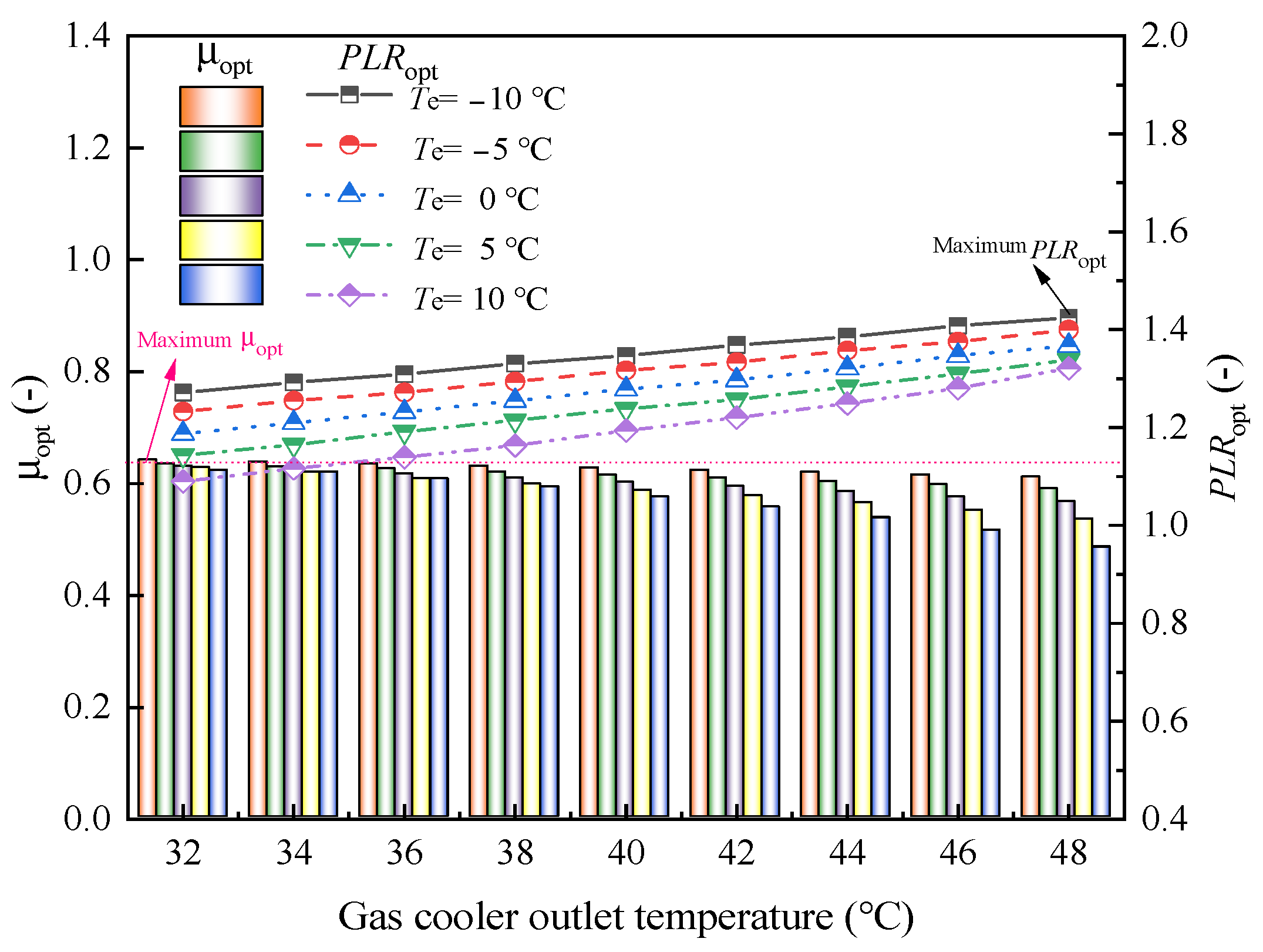

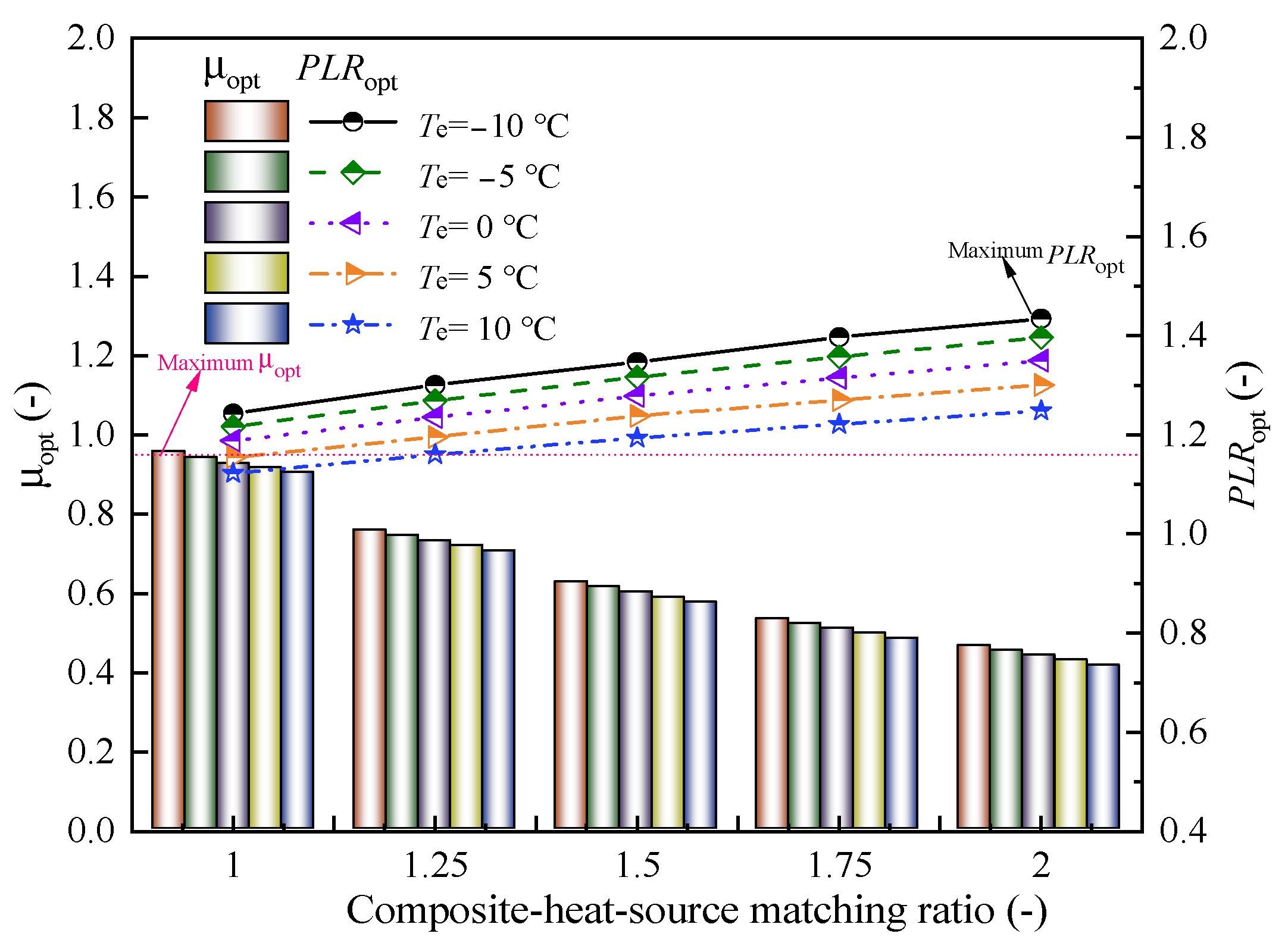

4.3. Ejector Performance

4.4. Compressor Pressure Ratio

4.5. Regression Analysis of Parameters

5. Conclusions

- (1)

- The maximum increase in the Popt,out,gc was 59.21% with the increase in the Tgc,out, and the maximum decrease in the Popt,out,gc was 3.13% with the increase in the Te, and the maximum decrease was 1.67% with the increase in the composite-heat-source matching ratio. The results showed that the Tgc,out had the greatest influence on the Pgc,out, and the effect of the composite-heat-source matching ratio was equally significant on the Popt,out,gc compared with the Te.

- (2)

- When designing or operating the CTHP system, a higher evaporator temperature, lower Tgc,out, and higher composite-heat-source matching ratio were found to be more successful in achieving both a lower optimum high-pressure side and maximum system COP. The maximum improvement ratio of the μopt is 32.14% with decreasing Tgc,out and Te, and that of the PLRopt is 30.69% with the increase in Tgc,out and the decrease in Te. The μopt decreases and PLRopt increases as the composite-heat-source matching ratio increases, and the maximum improvement ratios of μopt and PLRopt are 54.09% and 15.40%, respectively. The optimum high-pressure side governing equation of the CTHP system and the expressions for optimum cycle parameters of the CTHP system were obtained by multivariate nonlinear regression analysis.

- (3)

- The in-depth research on the reasonable matching of the high-temperature heat source and low-temperature heat source will be helpful for further development and optimization of the CTHP system, which is of great significance for the comprehensive utilization of renewable heat sources such as geothermal or air-source and the promotion of efficiency, environmental protection, and sustainable development in the fields of building and energy, etc. Future research may consider more factors, integrating performance parameters, cost parameters, and attempting to maximize performance as well as minimize costs, using an optimization method, such as machine learning or a genetic algorithm, to reduce the cost and improve the efficiency of energy utilization.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Symbols | Abbreviations | ||

| A | area (m2) | CTHP | compression/ejection trans-critical CO2 heat pump |

| a | volume fraction (-) | COP | heating coefficient of performance |

| c | velocity of sound (m/s) | TCHP | trans-critical CO2 heat pump |

| d | diameter (m) | CFCs | chlorofluorocarbons |

| f | exergoeconomic factor (-) | HCFCs | hydrochlorofluorocarbons |

| h | enthalpy (kJ·kg−1) | IHX | Internal heat exchanger |

| k | adiabatic exponent | Subscripts | |

| L | length (m) | he | high-temperature evaporator |

| P | pressure (kPa) | c | cooling |

| PLR | ejector pressure lift ratio (-) | cm | compressor |

| Q | heating capacity (kW) | dis | discharge |

| Re | Reynolds number (-) | e | evaporator |

| Rg | gas constant (kJ·kg−1·K−1) | g | gas |

| s | entropy (kJ·kg−1·K−1) | gc | gas cooler |

| T/t | temperature (K or °C) | h | heating |

| u | velocity (m·s−1) | l | liquid |

| W | compressor power consumption (kW) | max | maximum |

| degree of dryness (-) | opt | optimum | |

| ΔT | Superheat degree (°C) | out | outlet |

| compressor pressure lift ratio (-) | is | isentropic | |

| isentropic efficiency (%) | p | secondary flow of ejector | |

| viscosity/ejector entrainment ratio (Pa·s/-) | s | primary flow of ejector | |

| density (kg·m−3) | le | low-temperature evaporator | |

| composite-heat-source matching ratio (-) | 1–11, 4s, 4p state point | ||

| mass flow rate (kg·s−1) | |||

References

- Panigrahi, B.; Chang, C.W.; Hsieh, W.C.; Luo, W.J. Heating and defrosting performance assessment of dual-source heat pump operational modes under various ambient conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 89, 109359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, T.S.; Weng, Z.C.; Huang, R.; Hu, B.; Eikevik, T.M.; Dai, Y.J. High temperature transcritical CO2 heat pump with optimized tube-in-tube heat exchanger. Energy 2023, 283, 129223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, D.; Ma, K.; Yang, W. Experimental study on the influence of intermediate loop water supply temperature on the characteristics of air-water source coupling heat pump system. Geothermics 2025, 125, 103153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resende, S.I.d.M.; Diniz, H.A.G.; Machado, L.; de Faria, R.N.; de Oliveira, R.N. Dynamic modeling of an R290 direct-expansion solar-assisted heat pump: Performance analysis for efficient hot water production under different conditions. J. Build. Eng. 2025, 100, 111687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A.; Bradshaw, C.R. Quantitative comparison of the performance of vapor compression cycles with compressor vapor or liquid injection. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 154, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, F.; Ye, Z.; Wang, Y. Experimental investigation on the influence of internal heat exchanger in a transcritical CO2 heat pump water heater. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 168, 114855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okasha, A.; Müller, N.; Deb, K. Bi-objective optimization of transcritical CO2 heat pump systems. Energy 2022, 247, 123469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mancinelli, C.; Manno, M.; Salvatori, M.; Zaccagnini, A. Thermal energy storage as a way to improve transcritical CO2 heat pump performance by means of heat recovery cycles. Energy Storage Sav. 2023, 2, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, H.; Pei, J.; Niu, J.; Ding, C.; Guo, F.; Wang, Y. Hybrid offline and online strategy for optimal high pressure seeking of the transcritical CO2 heat pump system in an electric vehicle. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2023, 228, 120514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorentzen, G.; Pettersen, J. A New, Efficient and Environmentally Benign System for Automobile Air Conditioning. Int. J. Refrig. 1993, 16, 4–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Liu, H.; Meng, X.; Wei, X.; Zhao, L.; Yang, L. A study on the compressor frequency and optimal discharge pressure of the transcritical CO2 heat pump system. Int. J. Refrig. 2019, 99, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Peng, X.; Wang, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, D. Energetic and exergetic analysis of a transcritical CO2 air-source heat pump water heating system in the cold region. Energy Build. 2023, 298, 113558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.-X.; Wei, X.-L.; Zhao, L.-H.; Qin, X.; Zhang, D.-W. Experimental study on the effect of compressor frequency on the performance of transcritical CO2 heat pump system with regenerator. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2019, 150, 1216–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Cao, F. The evaluation of the optimal medium temperature in a space heating used transcritical air-source CO2 heat pump with an R134a subcooling device. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 166, 409–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, S.; Roy, R.; Mandal, B.K. A Review on Energy and Exergy Analysis of Two-Stage Vapour Compression Refrigeration System. Int. J. Air-Cond. Refrig. 2019, 27, 1930001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Huang, Y.; Li, C.; Zhang, F.; Jiang, P.-X. Experimental investigation on the performance of transcritical CO2 ejector–expansion heat pump water heater system. Energy Convers. Manag. 2018, 167, 147–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Cao, F. Comprehensive evaluation of the transcritical CO2 ejector-expansion heat pump water heater. Int. J. Refrig. 2023, 145, 276–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Liu, Y.; Xu, Y.; Ning, H.; Qin, Y.; Wang, Z. Performance of a solar ground source heat pump used for energy supply of a separated building. Geothermics 2022, 105, 102524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Li, N.; Tan, X.; Yongga, A.; Long, J.; Shen, X. Prediction of evaporation temperature in air-water heat source heat pump based on artificial neural network. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xueya, Z.; Guanwei, W.; Tao, H.; Rahman, M.A.; Aksoy, M.; Alenazi, M.J.F.; Saihua, X. Multi-criteria techno-economic and environmental optimization of PVT-assisted CO2 heat pump system for sustainable energy buildings in cold climates. Energy 2025, 335, 138243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, F.; Gao, Z.; Wei, X. Experimental and numerical study on heat transfer of gas cooler under the optimal discharge pressure. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 112, 229–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Qin, X.; Zhao, L.; Ye, S.; Wei, X.; Zhang, D. Analysis and comparison of influence factors of hot water temperature in transcritical CO2 heat pump water heater: An experimental study. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 198, 111836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, D.; Chen, J. System development and simulation investigation on a novel compression/ejection transcritical CO2 heat pump system for simultaneous cooling and heating. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 259, 115579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, D.; Gao, Z.; Tang, S. Experimental and theoretical analysis of the optimal high pressure and peak performance coefficient in transcritical CO2 heat pump. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2022, 210, 118372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wei, X.; Qin, X. Experimental study on energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses of a novel compression/ejector transcritical CO2 heat pump system with dual heat sources. Energy Convers. Manag. 2022, 271, 116343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, Y. Optimal compressor discharge pressure and performance characteristics of transcritical CO2 heat pump for crude oil heating. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 144, 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, C.; Zong, S.; Song, Y.; Yin, X.; Cao, F. Experimental investigation of the extreme seeking control on a transcritical CO2 heat pump water heater. Int. J. Refrig. 2022, 133, 111–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reis, H.O.; Paulino, T.F.; Machado, L.; Maia, A.A.; Duarte, W.M. Optimal high-pressure correlation for transcritical CO2 cycle in direct expansion solar assisted heat pumps. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 97, 110616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahammed, M.E.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Ramgopal, M. Thermodynamic design and simulation of a CO2 based transcritical vapour compression refrigeration system with an ejector. Int. J. Refrig. 2014, 45, 177–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kermani, A.A.; Houshfar, E. Design and energy, exergy, and exergoeconomic analyses of a novel biomass-based green hydrogen and power generation system integrated with carbon capture and power-to-gas. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2024, 52, 177–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Elbel, S. Experimental investigation into the influence of vortex control on transcritical R744 ejector and cycle performance. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2020, 164, 114418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, N.; Elbel, S. Experimental investigation on control methods and strategies for off-design operation of the transcritical R744 two-phase ejector cycle. Int. J. Refrig. 2019, 106, 570–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Deng, J.; Li, Y.; Ma, L. A numerical contrast on the adjustable and fixed transcritical CO2 ejector using exergy flux distribution analysis. Energy Convers. Manag. 2019, 196, 729–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhu, Y. Experimental and modeling studies of thermally-driven subcritical and transcritical ejector refrigeration systems. Energy Convers. Manag. 2020, 224, 113361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taslimi Taleghani, S.; Sorin, M.; Poncet, S. Modeling of two-phase transcritical CO2 ejectors for on-design and off-design conditions. Int. J. Refrig. 2018, 87, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.M.; Groll, E.A. Efficiencies of transcritical CO2 cycles with and without an expansion turbine. Int. J. Refrig. 1998, 21, 577–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahman, A.M.; Ziviani, D.; Groll, E.A. A generalized moving-boundary algorithm to predict the heat transfer rate of transcritical CO2 gas coolers. Int. J. Refrig. 2020, 118, 491–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Instrument | Description | Range | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital vortex flowmeter | LWYC-15 | 0~6 | ±0.5% |

| Temperature sensor | PT100 type | −50~200 °C | ±0.15% |

| Electromagnetic flowmeter | HXLD-25 | 0~15 | ±0.5% |

| Pressure transducer | HSTL-800 | 0~160 kPa | ±0.25% |

| Voltage | INVT GD200A | 0~380 V | ±1% |

| Input Parameters | #1 | #2 | #3 | #4 | #5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gas cooler outlet pressure (kPa) | 7840 | 7900 | 7980 | 8200 | 8380 |

| Gas cooler outlet temperature (°C) | 32.2 | 32.5 | 31.8 | 28.2 | 27.7 |

| Low-temperature evaporator inlet temperature (°C) | 22.43 | 22.36 | 21.58 | 19.56 | 19.17 |

| Low-temperature evaporator Outlet superheat (°C) | 1.09 | 1.04 | 1.22 | 1.24 | 1.21 |

| Cooling capacity of high-temperature evaporator (kW) | 36.21 | 35.10 | 34.76 | 33.02 | 32.02 |

| Cooling capacity of low-temperature evaporator (kW) | 7.73 | 7.34 | 7.20 | 7.28 | 7.17 |

| Parameters | Popt,out,gc | COPc,max | COPh,max | μopt | PLRopt | γopt |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Root Mean Square Error | 52.3598 | 0.1076 | 0.1111 | 0.0275 | 0.0273 | 0.0555 |

| Sum of Squared Residuals | 68,538.72 | 0.2893 | 0.3084 | 0.0189 | 0.0186 | 0.0770 |

| Correlation Coefficient | 0.9997 | 0.9954 | 0.9951 | 0.9872 | 0.9764 | 0.9935 |

| Chi-square | 3.4362 | 0.0371 | 0.0308 | 0.0179 | 0.0075 | 0.0174 |

| F-statistic | 3767.2451 | 265.5271 | 244.9293 | 93.4033 | 49.8385 | 186.0757 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qin, X.; Zhao, M.; Chen, Y. Performance Enhancement of a Novel Compression/Ejection Trans-Critical CO2 Heat Pump System Coupled with Composite Heat Sources. Energies 2025, 18, 5657. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215657

Zhang Y, Zhang X, Qin X, Zhao M, Chen Y. Performance Enhancement of a Novel Compression/Ejection Trans-Critical CO2 Heat Pump System Coupled with Composite Heat Sources. Energies. 2025; 18(21):5657. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215657

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Yuxiang, Xiao Zhang, Xiang Qin, Min Zhao, and Yuhui Chen. 2025. "Performance Enhancement of a Novel Compression/Ejection Trans-Critical CO2 Heat Pump System Coupled with Composite Heat Sources" Energies 18, no. 21: 5657. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215657

APA StyleZhang, Y., Zhang, X., Qin, X., Zhao, M., & Chen, Y. (2025). Performance Enhancement of a Novel Compression/Ejection Trans-Critical CO2 Heat Pump System Coupled with Composite Heat Sources. Energies, 18(21), 5657. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18215657