Lignite in Polish State Policies as a Regulatory Instrument

Abstract

1. Introduction

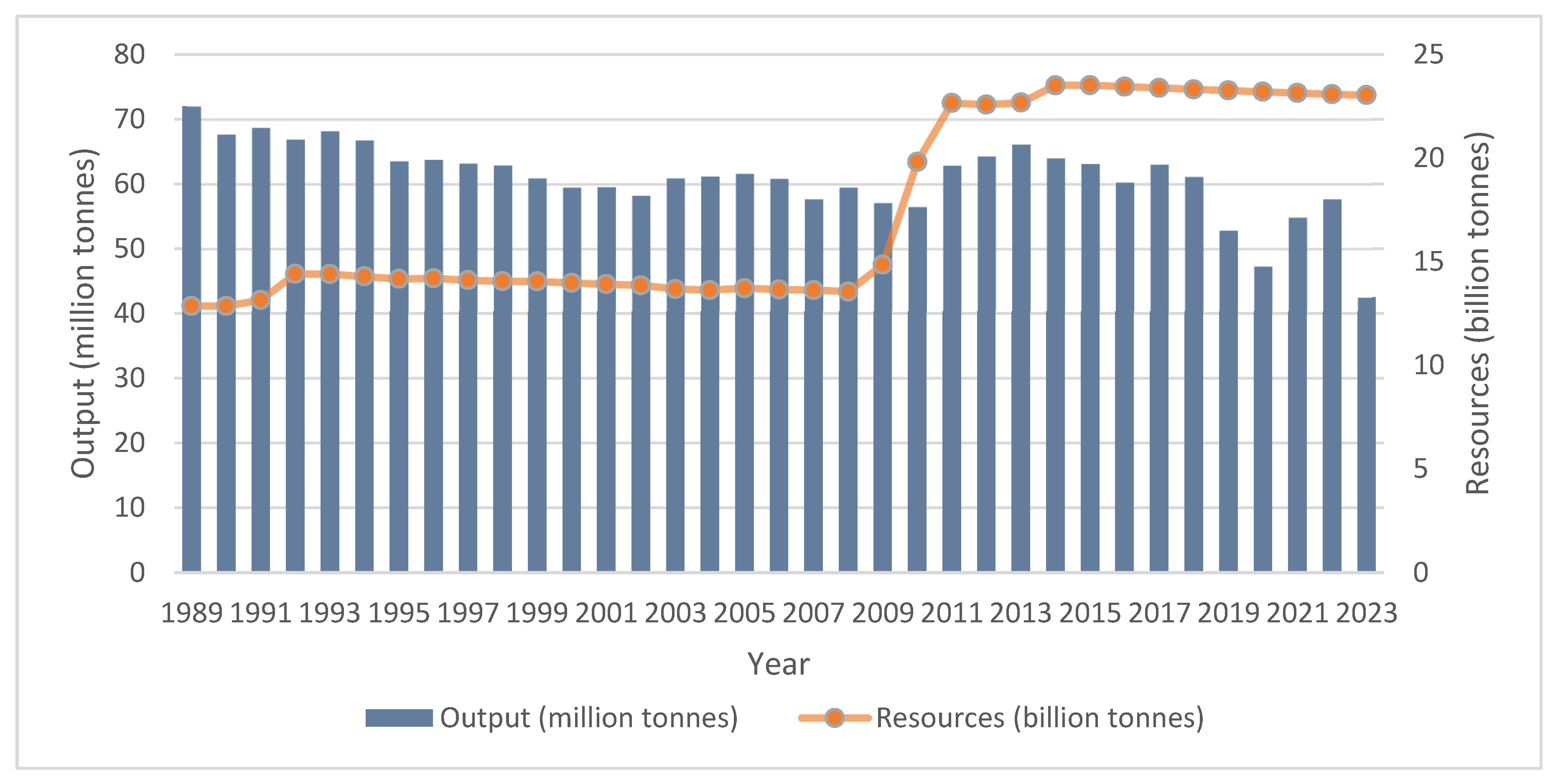

2. Lignite Deposits in Poland

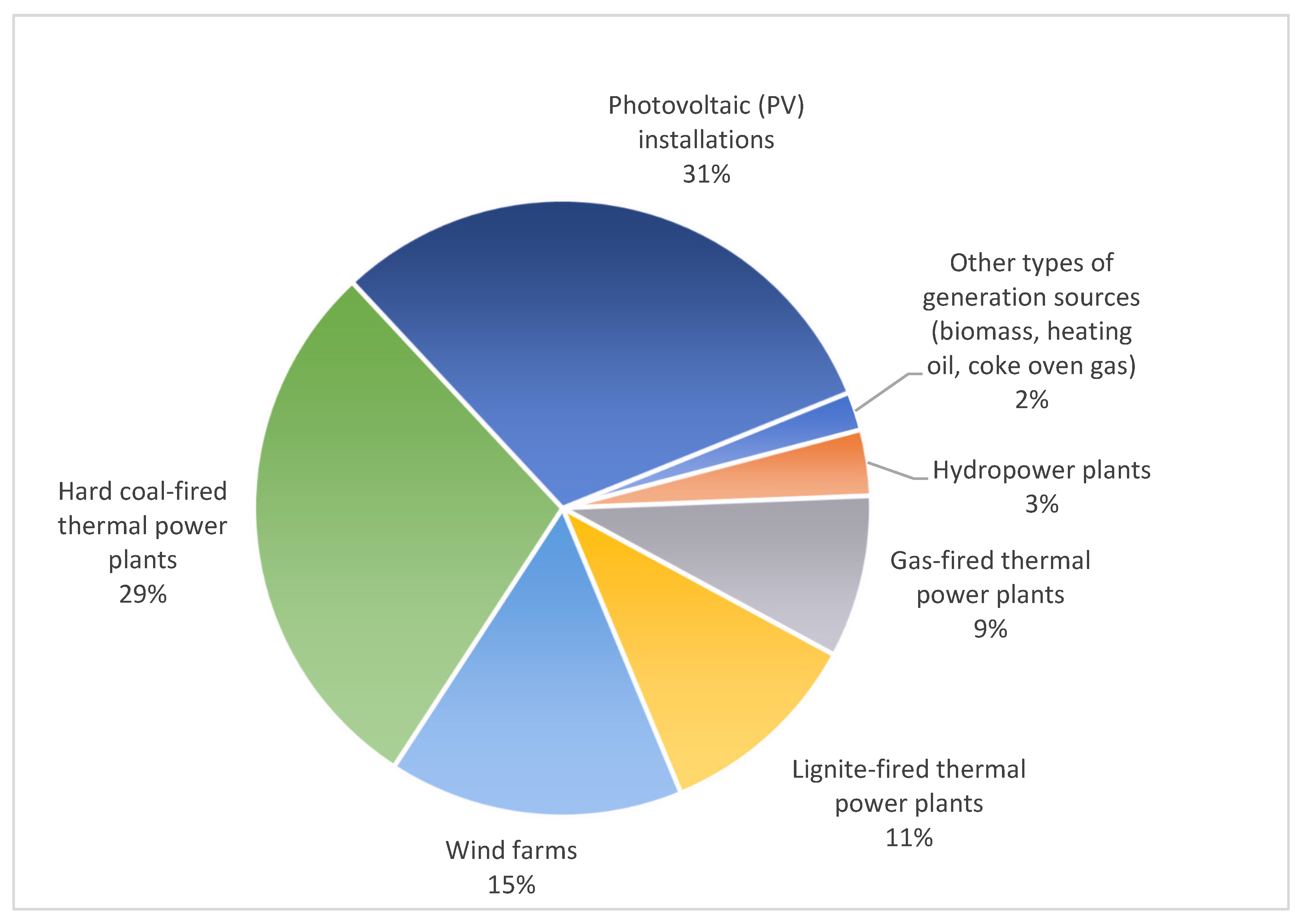

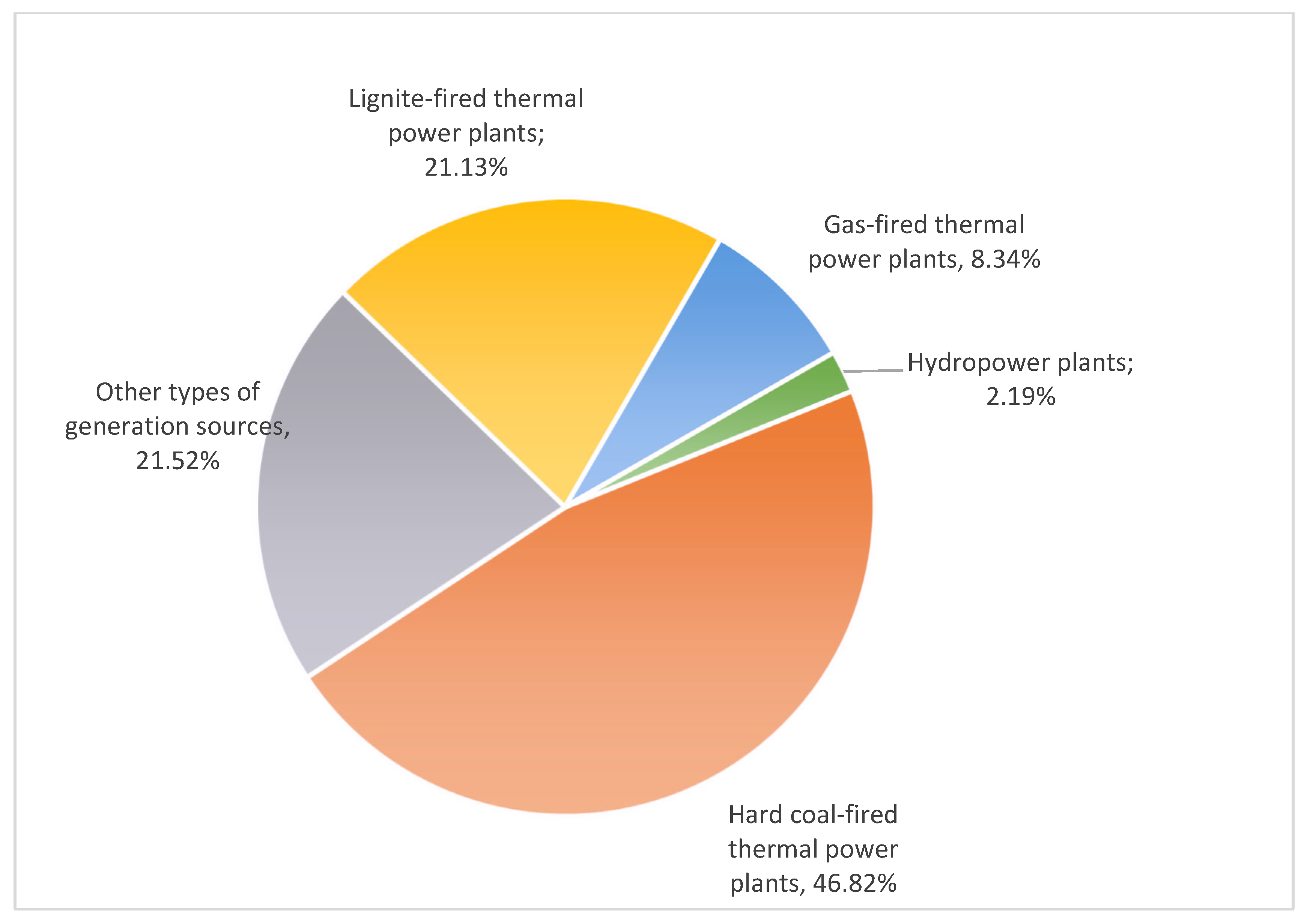

3. Lignite-Based Power Generation

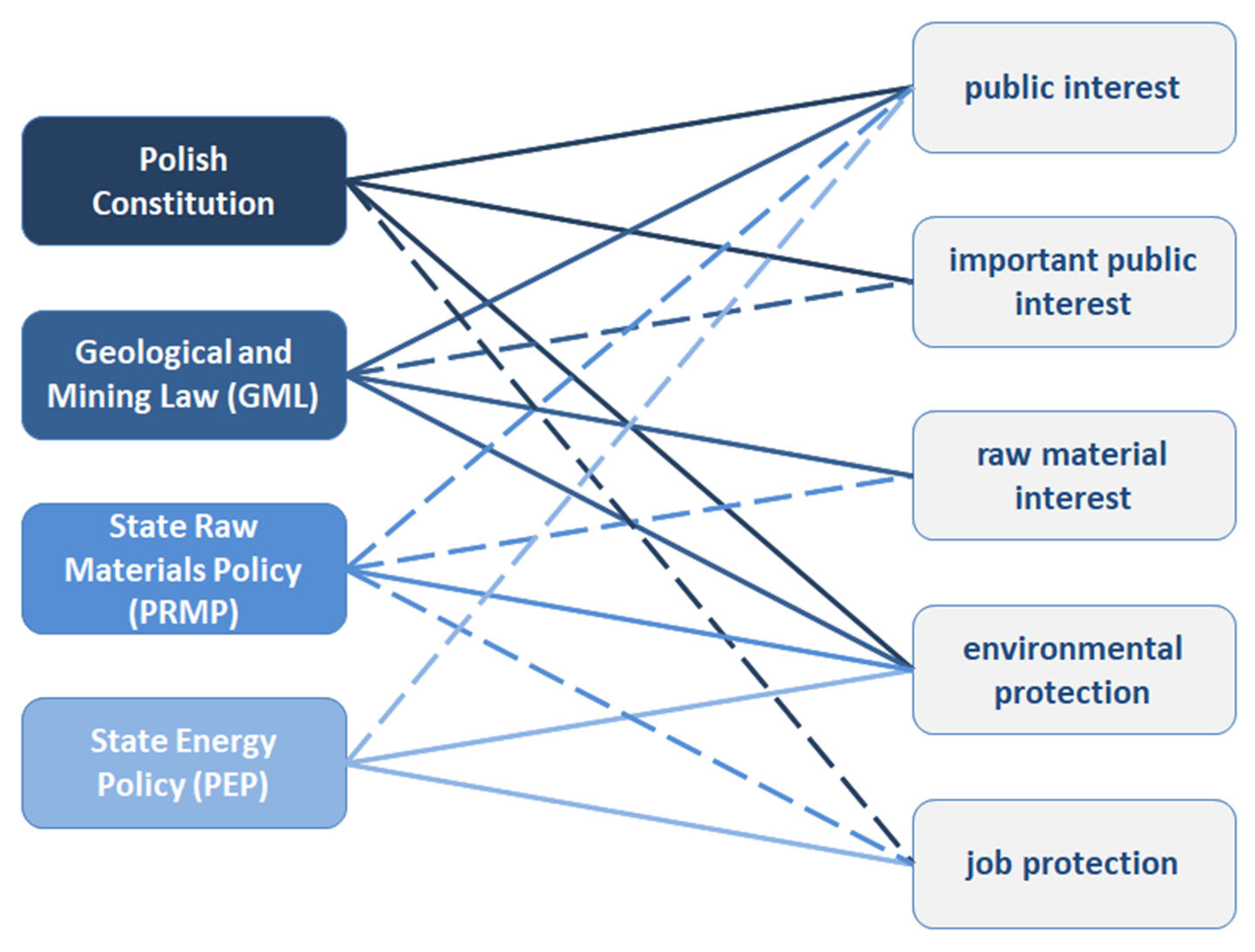

4. State Policies in Poland

4.1. National Policy Anchor

- (1)

- Public policy constitutes one of several formal instruments used to implement national development policy (others include development strategies, programs, and programmatic documents, such as partnership agreements, and also legal and financial instruments specified in legal regulations);

- (2)

- Both the Council of Ministers and individual ministers are obliged to implement public policies in accordance with the guidelines they contain.

- (1)

- Conclusions from the diagnosis of the social, economic, and spatial situation, prepared for the needs of this policy, in relation to the field or area covered by this policy;

- (2)

- Strategic objectives in the scope of this policy, taking into account the medium-term national development strategy and possibly another appropriate strategy;

- (3)

- Directions of intervention in the scope of this policy, taking into account the medium-term national development strategy and possibly another appropriate strategy;

- (4)

- Principles of implementation of this policy.

4.2. Public Policies and Sources of Law

- (1)

- The Constitution;

- (2)

- Statutes;

- (3)

- Ratified international agreements;

- (4)

- Regulations;

- (5)

- Local law acts—within the area of operation of the bodies that established them.

4.3. State Energy Policy

- -

- Protection of documented mineral deposits (unconditionally in the case of prospective and reserve deposits);

- -

- Conducting rational management of deposit resources;

- -

- The development and implementation of new, cleaner technologies for lignite processing.

4.4. State Raw Material Policy

5. Instruments of Regulation

5.1. Legal Nature of the Concession

- (1)

- Whether the list of grounds for refusal is closed or open;

- (2)

- Whether the refusal is obligatory or merely optional once such grounds are established.

5.2. General Clauses as Grounds for Refusing to Grant a Concession

- -

- First, the interpretation of the notion of “important public interest” must not be detached from the values protected under the principle of a democratic state governed by the rule of law. The introduction of restrictions on the freedom of economic activity that merely serve a statutory purpose, yet lack justification grounded in the values of a democratic rule-of-law state, constitutes a violation of Article 22 of the Constitution.

- -

- Second, only those restrictions on economic freedom that—in addition to being useful—serve the protection of state security, public order, the environment, public health, or the rights and freedoms of other persons, will be consistent with Article 22 of the Constitution. Not every public interest justifies a restriction on economic freedom; only such an interest that may be constitutionally recognised as “important” meets this threshold (cf. findings in judgment Kp 1/09).

- -

- Third, the interpretation of the term “important public interest” is inseparably linked to the internal hierarchy of constitutional values. The more valuable the interest being restricted, and the more severe the restriction, the more compelling the value must be that justifies such a limitation.

- -

- Fourth, the grounds that may justify statutory restrictions on the freedom of economic activity are not subject to expansive interpretation” [36].

6. The State’s Raw Material Interest as a Basis for Refusing to Grant a Concession

- (1)

- Cannot be extended to include issues other than those strictly related to the raw material interest;

- (2)

- May therefore include only matters directly concerning mineral resources, and thus—for example, include the following:

- (a)

- Protection of the national resource raw materials base;

- (b)

- Ensuring the availability of essential raw materials for domestic industry;

- (c)

- Striving for self-sufficiency in raw materials (or reducing excessive dependence on foreign supply);

- (d)

- Stimulating the development of the mining industry to secure future demand for critical raw materials (e.g., for technologies still in the development phase).

- (a)

- Constitutional values, such as the obligation to protect mineral deposits;

- (b)

- Strategic policy documents issued by the Council of Ministers related to raw material governance, such as the State Raw Materials Policy and the State Energy Policy, as well as sectoral strategies applicable to non-energy industries;

- (c)

- Academic and technical publications on the national mineral resource base, the availability of raw materials for domestic industry (including sources of import), and other issues relevant to raw material security.

- (a)

- Addresses as comprehensively as possible the issues outlined above in relation to raw materials, including current demand, projected future demand, and strategic directions for sourcing raw materials for the Polish economy;

- (b)

- Is up-to-date, meaning that it reflects the current state of knowledge.

- (a)

- The number of concessions granted for the exploration, identification, and extraction of mineral deposits (excluding hard coal and lignite);

- (b)

- The number of approved geological work projects;

- (c)

- The number of drillings conducted, as follows:

- -

- Under concessions for exploration or identification carried out by private operators;

- -

- As part of the tasks performed by the entity acting as the state geological service.

7. Summary and Conclusions

- (1)

- It is constitutionally permissible—pursuant to Article 22 of the Polish Constitution—to introduce statutory restrictions on economic activity on the grounds of the public interest. Consequently, the inconsistency of a proposed undertaking with the state’s raw material interest, understood as a distinct component of the public interest, may constitute an independent legal basis for refusing to grant a concession.

- (2)

- In each concession procedure, the licensing authority is required to assess the relevance of the state’s raw material interest in light of the specific circumstances of the case. Given the nature of this concept as a general clause, it cannot be assigned an abstract or universal meaning detached from the factual context. In other words, invoking the public interest as a basis for concession refusal must be concretely justified; the authority must explicitly identify which type of public interest—e.g., raw material interest—underpins its decision in a given case.

- (3)

- As an element of the public interest, the state’s raw material interest must be interpreted in light of other constitutional values, and its application is subject to the limitations imposed by the principle of proportionality, as enshrined in Article 31(3) of the Constitution.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Act of 9 June 2011—Geological and Mining Law (Consolidated Text Published in the Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 1290); Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2011.

- Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 2 April 1997 (Journal of Laws No. 78, Item 483—As Amended and Corrected); Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 1997.

- Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 39/2022 of March 1, 2022, Monitor Polski Item 371; Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2022.

- Resolution of the Council of Ministers No. 22/2021 of February 2, 2021, Monitor Polski Item 264; Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2021.

- Widera, M.; Naworyta, W.; Urbański, P. Polish energy sector’s dependence on lignite mining: The process of transition. J. Sustain. Min. 2024, 23, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gierszewski, J.; Młynarkiewicz, Ł.; Nowacki, T.R.; Dworzecki, J. Nuclear Power in Poland’s Energy Transition. Energies 2021, 14, 3626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polish Geological Institute—National Research Institute; National Balance of Mineral Resources, Collective Work; Warsaw, Poland, 2024; p. 35.

- Kubik, M.; Coker, P.; Hunt, C. The role of conventional generation in managing variability. Energy Policy 2012, 50, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Act of 6 December 2006 on the Principles of Development Policy (Journal of Laws of 2024, Item 324—As Amended); Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2006.

- Stahl, M. Administrative Law System. Legal Forms of Administration, Volume 5; Hauser, R., Niewiadomski, Z., Wróbel, A., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; p. 366. [Google Scholar]

- Radziewicz, P. Constitution of the Republic of Poland. Commentary, 2nd ed.; Tuleja, P., Ed.; LEX/el. Commentary on Article 87 of the Constitution of the Republic of Poland; Sejm Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej: Warsaw, Poland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Garlicki, L. Administrative Law System. Constitutional Foundations of Public Administration; Hauser, R., Niewiadomski, Z., Wróbel, A., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2012; Volume 2, p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Bałaban, A. Internally binding normative acts. In The Constitutional System of Sources of Law in Practice; Szmyt, A., Ed.; Wydawnictwo Sejmowe: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; p. 100. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry of Energy, Program for the Lignite Mining Sector in Poland; Ministry of Energy: Warsaw, Poland, 2018; p. 42.

- Schwarz, H.; Walczak, M.; Kasztelewicz, Z. Miners’ pension as an element of energy transformation. Civ. Environ. Eng. Rep. 2025, 35, 0205–0221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urbański, P.; Widera, M. Is the Złoczew lignite deposit geologically suitable for the first underground gasification installation in Poland? Geologos 2020, 26, 113–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widera, M.; Urbański, P.; Mazurek, S.; Naworyta, W. Polish lignite resources, mining and energy industries—What is next? Gospod. Surowcami Miner.—Miner. Resour. Manag. 2024, 40, 5–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikos-Szymańska, M.; Schab, S.; Rusek, P.; Borowik, K.; Bogusz, P.; Wyzińska, M. Preliminary Study of a Method for Obtaining Brown Coal and Biochar Based Granular Compound Fertilizer. Waste Biomass Valorizat 2019, 10, 3673–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kosikowski, C. Polish Public Economic Law; Legal Publishing House LexisNexis: Warsaw, Poland, 1998; p. 210. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, H. Geological and Mining Law. Commentary. Volume I. Art. 1-103; Oficyna Wydawnicza Uniwersytetu Wrocławskiego: Wrocław, Poland, 2013; pp. 181–182. [Google Scholar]

- Szydło, W. The scope of discretionary power and cooperation of local government authorities in granting geological and mining concessions. Samorz. Teryt. 2014, 11, 45–60. [Google Scholar]

- Szydło, M. The Concept of Concession in the Classical Approach and Its Reception in Polish Law; PiP 2004/1; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2004; p. 46. [Google Scholar]

- Szydło, M. Granting a Concession for Business Activity. In The Right to Good Administration: Materials from the Congress of the Departments of Administrative Law and Procedure, Warszawa–Dębe, 23–25 September 2002; Niewiadomski, Z., Cieślak, Z., Eds.; Faculty of Law and Administration, University of Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2003; p. 662. [Google Scholar]

- Gola, J. Commentary on the Act—Entrepreneurs’ Law. In The Constitution of Business. Commentary; Bielecki, L., Horubski, K., Kokocińska, K., Komierzyńska-Orlińska, E., Żywicka, A., Gola, J., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Art. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Kosikowski, C. Concessions and Permits for Conducting Business Activities; LexisNexis Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2002; p. 64. [Google Scholar]

- Tracz, P. Entrepreneurs’ Law. Commentary; Pietrzak, A., Ed.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Art. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Sieradzka, M.; Zdyb, M. The Act on Freedom of Economic Activity. Commentary; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Szydło, M. Freedom of Economic Activity; C.H. Beck: Warsaw, Poland, 2005; p. 236. [Google Scholar]

- Machnikowski, P. Civil Code. Commentary; Gniewek, E., Machnikowski, P., Eds.; C.H. Beck: Warsaw, Poland, 2013; p. 14. [Google Scholar]

- Wyrzykowski, M. The Concept of Public Interest in Administrative Law; Państwowe Wydawnictwo Naukowe (PWN): Warsaw, Poland, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann, J. Administrative Law; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2010; pp. 264–265. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, H. Rational management of deposits in geological and mining law. In Legal Regulation of Geology and Mining in Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia. Selected Issues; Dobrowolski, G., Radecki, G., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Śląskiego: Katowice, Poland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Pchałek, M. Environmental Protection Law. Commentary; Górski, M., Pchałek, M., Radecki, W., Jerzmański, J., Bar, M., Urban, S., Jendrośka, J., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2011; Commentary on Art. 125. [Google Scholar]

- Tuleja, P. The Constitution of the Republic of Poland. Commentary, 2nd ed.; Czarny, P., Florczak-Wątor, M., Naleziński, B., Radziewicz, P., Tuleja, P., Eds.; Wolters Kluwer Polska: Warsaw, Poland, 2023; Art. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 17 December 2003; File Reference: SK 15/02; Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2003.

- Garlicki, L. Constitution of the Republic of Poland. Commentary. Volume I; Garlicki, L., Zubik, M., Eds.; Wydawnictwo Sejmowe: Warsaw, Poland, 2016; Commentary to Article 22. [Google Scholar]

- Judgment of the Constitutional Tribunal of 16 October 2014; File Reference: SK 20/12; Chancellery of the Prime Minister: Warsaw, Poland, 2014.

- Judgment of the Provincial Administrative Court in Warsaw of 30 October 2019; File Reference Number: VI SA/Wa 556/19; Provincial Administrative Court in Warsaw: Warsaw, Poland, 2019.

| Legal Clause | Ground for Refusal | Type of Refusal |

|---|---|---|

| Art. 29(1) | Refusal is required if the intended activity contradicts public interest, including:

| Mandatory |

| Art. 29(1a) | Refusal is required if the application overlaps in area and activity (or mineral type in case of exploration/extraction) with an existing valid concession. | Mandatory |

| Art. 29(2) | Refusal is required for underground waste storage if technically, environmentally, or economically justified alternatives exist. | Mandatory |

| Art. 29(3) | Refusal is permitted if public interest is at stake following a decision under the Act on control of certain investments (e.g., national security, environmental protection, rational resource use). | Discretionary |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schwarz, H.; Kasztelewicz, Z.; Nowak-Szpak, A. Lignite in Polish State Policies as a Regulatory Instrument. Energies 2025, 18, 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18123098

Schwarz H, Kasztelewicz Z, Nowak-Szpak A. Lignite in Polish State Policies as a Regulatory Instrument. Energies. 2025; 18(12):3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18123098

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchwarz, Hubert, Zbigniew Kasztelewicz, and Anna Nowak-Szpak. 2025. "Lignite in Polish State Policies as a Regulatory Instrument" Energies 18, no. 12: 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18123098

APA StyleSchwarz, H., Kasztelewicz, Z., & Nowak-Szpak, A. (2025). Lignite in Polish State Policies as a Regulatory Instrument. Energies, 18(12), 3098. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18123098