Abstract

As it has an export-oriented economy, Taiwan urgently needs to keep up with the growing trends toward carbon taxation. However, making the institution of a carbon tax a reality in Taiwan has proven to be difficult. Since 1998, Taiwan has explored the possibility of putting a tax on carbon many times. Specifically, three main windows of opportunity emerged to adopt a carbon tax during this period; however, all of them failed. This study mainly explores why these three opportunities failed, what structural factors hindered them, and how those structural factors formed path dependence and locked the entire society back onto the existing development track. Firstly, Taiwan’s high-carbon industrial structure has established the rapid growth of energy-intensive industries since the end of the 1990s and has created an economy with high energy consumption and pollution levels. Secondly, this analysis showed that through the combination of government bureaucracy, industry, and the China National Federation of Industries, this brown economy and high-carbon emission structure generated institutional, cognitive, and techno-institutional complex lock-ins, which have led Taiwan to its current path and hindered its transformation. Thirdly, under the above framework, this study further analyzes the contexts and problems that caused the three windows of opportunity to fail. Finally, by linking the economy-first orientation of developmental states, this study identifies structural difficulties and possible breakthrough conditions for newly industrialized/industrializing countries that are undergoing low-carbon transitions.

1. Introduction

By 2020, there were 30 countries that had already implemented or were scheduled to implement a carbon tax, including South Africa and Singapore, both of which began to implement their carbon tax in 2019 [1]. At the end of 2019, the European Union (EU) adopted the European Green Deal. The EU aims to achieve a legally binding target of net zero greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050 through the adoption of the European Climate Law. The EU is also introducing the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) to prevent carbon leakage from other countries into the EU and encourage carbon taxation in other countries.

The question is, how should Taiwan respond to this global carbon taxation trend? As Taiwan’s energy is highly dependent on fossil fuels, its energy efficiency remains low, industrial policies rely heavily on manufacturing, and energy consumption levels and GHG emissions remain obstinately high [2]. The 2019 CO2 Emissions Statistics showed that Taiwan’s energy-related CO2 emissions were 268.9 tons in 2017, accounting for 0.82% of global energy-related CO2 emissions [3] and making Taiwan the world’s 21st highest CO2 emitter. With a per capita emissions rate of 11.38 tons per year, Taiwan has the 19th highest per capita emissions rate in the world. In terms of emissions intensity, Taiwan is in 45th place with emissions of 0.26 kg CO2 per USD.

Over the past 20 years, Taiwan has made three attempts to introduce a carbon tax. A Taiwanese carbon tax was discussed for the first time at the first National Energy Conference in 1998. In 2006, the Executive Yuan and the Legislative Yuan separately drafted different versions of an Energy Tax Bill. In 2009, the Ministry of Finance’s Taxation Reform Commission, which was mandated by the Executive Yuan, initiated comprehensive research into a green taxation system, which included a carbon tax and an energy tax. Subsequent to this research, an Energy Tax Bill was introduced.

By 2015, Taiwan had officially adopted the GHG Reduction and Management Act, which incorporated both the concepts of a tax and a levy on GHGs. However, despite the 20 years of development, the implementation of an energy tax, with its potential to begin the transition away from a high-carbon economy, has yet to occur. As Aklin et al. clearly pointed out, sustainable energy transitions are fundamentally political and require government interventions, such as carbon taxation instruments [4].

This study mainly aimed to explore what kind of industrial, social, and political factors caused the three windows of opportunity that emerged in Taiwan to fail and illuminate their structural difficulties, including the low-carbon transition challenges that are faced in Taiwan. Under this framework, this study first analyzed the development of high-carbon industries in Taiwan since the late 1990s, especially the petrochemical industry, which drove the increase in Taiwan’s carbon emissions from 1996 to 2017 and established its high-carbon economic structure. Secondly, this study investigated how high-carbon industries and the brown economy have inherently generated institutional, cognitive, and techno-institutional complex (TIC) lock-ins under the combination of the government, industry, and the Chinese National Federation of Industries (CNFI), which has resulted in path dependence and has locked Taiwan into its current development track and hindered its transformation. Thirdly, this study analyzed the contexts and problems of the three windows of opportunity for energy taxation, examined the fundamental challenges of the low-carbon transition, and reflected on the similar challenges that are faced by newly industrialized/industrializing countries from a broad perspective.

Accordingly, Section 2 investigates the path dependence of the carbon lock-in effect and analyzes how cognitive, systemic, technological, and economic models resist the transition toward a low-carbon society. In this analysis, this study specifically referred to the role of lobbying by carbon-intensive industries, the prioritization of economic interests in East Asia, and the developmental environmentalism that it gives rise to. Section 3 summarizes our method. Section 4 incorporates our findings into an analysis of Taiwan’s brown economy. In this analysis, this study explored the negative influence of Taiwan’s high-carbon dependency, which drove the failure of the three windows of opportunity to introduce a carbon tax. Finally, Section 5 provides our concluding remarks, which highlight the reinforced carbon lock-in effect from the high-carbon regime with a developmental state issue. This last section also analyzes the possibility of breaking the barriers toward low-carbon transition.

2. Theoretical Framework: Path Dependence and the High-Carbon Regime

2.1. Path Dependence: The Carbon Lock-In Effect

Transitions away from pre-existing social systems face challenges in path dependence. These challenges range from cognitive and institutional issues to technical and economic problems. These complicated and persistent barriers to change are deeply embedded within society. They hinder social and economic transitions and keep nations locked onto specific tracks. With the challenges of technological bias, dominated networks, and administrative agency in play, social transformations and technological innovations become hampered [5,6].

Unruh explored how post-industrial economies could be locked into dependency on fossil fuel energy via the techno-institutional complex (TIC) [7]. The TIC comprises the systemic interactions between the elements of large and complex technological systems and powerful institutions. In turn, this kind of path dependence cements the carbon lock-in effect. Large-scale technical systems, such as the electricity system, are deeply embedded in both public and private organizations and create, deploy, and expand interests derived from the TIC. Once the TIC is established, this kind of complex becomes difficult to disengage from, leading societies to reject even the possibility of transition.

Seto et al. [8] similarly suggested that the carbon lock-in effect could be attributed to the intertwined nature of technology, organizations, and behavior patterns. The interplay between these factors has enabled public and private organizations to construct basic infrastructures and technologies that have a long history of high carbon emissions. They have achieved this through large-scale investments, scientific research efforts, and policy support. In turn, the constant increases in returns on these investments have consolidated the high-carbon system and the resulting inertia has only made actors in the system even more unwilling to initiate low-carbon transitions.

Moreover, lock-in effects are mutually reinforcing, and systemic inertia is not individual but collective. The carbon lock-in effect does not exist autonomously, but rather it is strengthened by systemic interactions within the TIC. Therefore, identifying and breaking away from the carbon lock-in effect is fundamentally time-consuming. However, it is still possible to drive transitions toward carbon lock-out if enabling environments are created and external pressure is applied [9,10]. The enabling environments need large-scale investments and flexible policies. The application of external pressure requires attentive and motivated stakeholders and the creation of a window of opportunity [8].

Aghion et al. [11] mainly focused on analyzing path dependence in innovation processes. Powerful network effects and high switching costs create path dependence and delay the deployment and adoption of clean technologies. Therefore, institutions should ideally be capable of designing policy instruments that can limit lobbying, rent-seeking, and the control of governments by high-carbon industries.

Pierson [12] argued that the combination of the central role of change-resistant institutions, the use of political authority to magnify power asymmetries, and the ambiguities that arise in political processes and outcomes could produce power consolidation in and increase returns to the dominant system. More fundamentally, Rotmans and Loorbach [13] suggested that breaking through systemic malfunctions requires the reorganization of social systems coupled with the reconfiguration of social development and values before transition opportunities can be realized.

Carbon-intensive industries tend to form tight policy communities that aim to influence carbon taxation policies. Kasa [14] compared institutionalized networks, the degree of internal consensus, balanced power resources, and mutual economic interests between two different groups of carbon-intensive industries. He concluded that the greatest influence on Norway’s carbon tax was the political power of interest groups rather than their individual contributions to the GDP.

Even when some interest groups support carbon taxation, it may still be impossible to circumvent the lobbying power of carbon-intensive industries. Svendsen [15] analyzed the power of opposition lobbying by carbon-intensive industries in OECD countries. They found that lobbying in support of carbon-intensive industries remains fierce, even though these same carbon-intensive industries pay six times less for their carbon emissions than normal households. In fact, in the case of Norway, despite having already acquired rebates on their carbon tax, the strength and influence of the lobbyists’ opposition maintain these unfair tax differentials.

Although there is disagreement about the potential efficiency of carbon taxation, the impacts are relatively focused. Such a focus may allow carbon-intensive industries to join together in a unified position, which would enable them to benefit from the policies that determine the taxation system to be adopted [16].

2.2. The East Asian Factor

Kawakatsu, Rudolph, and Lee [17] analyzed the barriers to the introduction of carbon taxation in Japan, China, South Korea, and Taiwan. They found that the core barrier is the paradigm of continuous economic growth combined with a lack of awareness of the damage caused to the global climate by the use of fossil fuels and nuclear power. In addition, East Asian governments have adopted the mindset that the best path toward a low-carbon future is to focus on building up next-generation industries and maintaining energy security, while GHG reduction and other environmental improvements tend to be seen as side benefits.

The climate change policy promoted by Lee Myung-bak’s government in South Korea is often referred to as “environmental developmentalism”, which follows the same developmental strategy and mindset that were evident in historic state-led macroeconomic planning. While that government was successful in introducing a Korean carbon emission trading system, the national low-carbon strategy initiated by Lee remained firmly under the control of the state and colluded with the chaebol. It also excluded the participation of environmental groups and emphasized a “Korean” version of green development, which, in reality, neglected both environmental protection and social welfare [18].

In terms of how the South Korean government interacted with international climate conventions, Dent [19,20] concluded that the Korean government’s main goal was to promote green industries over low-carbon transition. Dent described this promotion as “new developmentalism”. The Low-Carbon Green Growth strategy initiated by Lee’s government was embedded in the same developmental environmentalism regime and lacked a thorough framework for climate governance [21].

In terms of Japan’s experience, Kameyama [22] illustrated how the Japanese Business Federation (Keidanren) hindered the introduction of a Japanese carbon tax by promoting discourse about how it could interfere with industrial competitiveness and impose economic burdens on households. In March 2019, when Japan hosted the G20 summit, Keidanren released statements expressing its opposition to a carbon tax and other taxation systems just before the summit began. Keidanren argued that such taxation systems would damage the Japanese economy and even suggested that the move would hinder investments in the research and development of low-carbon technologies [23].

It is also very common to see industrial groups joining with governments and academics to create vast interest groups, such as “the nuclear village” in Japan and “the nuclear mafia” in South Korea. These kinds of interest groups tend to lobby for their vested interests, manipulate the media, bury data, and generally hamper efforts toward low-carbon transitions [24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31].

A similar nuclear complex also exists in Taiwan, which is deeply embedded in the discussions about the Taiwanese energy transition. These discussions are centered on debates about the potential role of nuclear power in achieving a low-carbon transition. In reality, the Taiwanese nuclear–coal complex has created complex relationships between maintaining nuclear energy, reducing carbon emissions, and maintaining the brown economy, which together keep social development locked onto its current track [32].

In summary, national low-carbon reforms face a variety of challenges that arise from governing regimes, dominant economic models, and different vested interests. Political windows of opportunity are needed to enable the Taiwanese government to overcome these traditional power structures.

In light of these findings, this study analyzed the various political opportunities that have arisen for the implementation of a carbon tax in Taiwan and investigated the barriers that have been encountered. This study aimed at an examination of the following questions: (1) Why has the implementation of a carbon tax been repeatedly delayed? (2) What kind of path dependence has caused difficulties for energy reform? (3) How has locking social reforms onto the current industrial, economic, and energy paths caused transition delays?

3. Methods

3.1. Identification of the High-Carbon Regime and the Carbon Lock-In Effect

The high-carbon regime includes GHG emissions, which are dominated by energy-intensive manufacturers and the brown economy complex. These are shaped by long-term subsidies for electricity, water, and labor. The high-carbon regime has been recognized in the energy policy literature and the gray literature. In addition, our analysis of institutional, cognitive, and techno-institutional lock-ins included insights gained from stakeholders, independent experts, and focus groups.

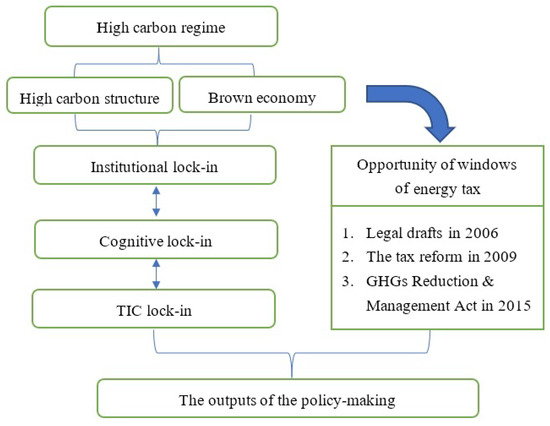

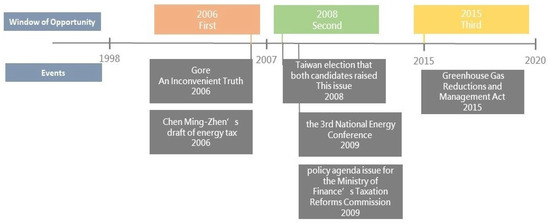

Using these methods, this study further characterized and explained the three failed policy windows for introducing an energy tax. Figure 1 shows the structure of our analytical approach, which centered on the high-carbon brown economy and its generation of environmental externalities and dependence on subsidies. These forces have consolidated the high-carbon path dependence and have explicitly blocked three policy opportunity windows for the implementation of an energy tax.

Figure 1.

The three windows of opportunity that were undermined by the high-carbon economic and political regime of Taiwan. Source: made by authors.

Firstly, using this analytical approach, this study outlined the deep linkages between the high-carbon regime and the institutional, cognitive, and TIC lock-ins, which are characterized by contextual and close interest relationships. Secondly, through this approach, this study further explored the complicated developments of the three windows of opportunity for energy tax implementation. Accordingly, these factors resulted in the delay of a low-carbon transition due to structural path dependence.

3.2. Data Collection

Our fieldwork and data collection took place from May 2020 to December 2021. In total, five focus groups were conducted with 29 participants, including governmental agencies, such as the Taiwanese Environmental Protection Agency, the Bureau of Energy, the Industrial Development Bureau, and the National Development Council. Participants also included representatives from industry, academia, different parliamentary parties, and NGOs (see Appendix A). The questions for the focus groups were formulated and sent to each participant in advance. The focus group discussions focused on past attempts to introduce an energy tax, how these policies were made, and the viewpoints of industry on these policies. Among other things, we asked the participants whether the policy processes had been sufficiently inclusive and about the nature of civil society responses to energy taxation policies. The results were recorded and transcribed.

One of the authors participated in 12 symposiums and events, including public survey conferences, risk society forums, and meetings on net zero and sustainability targets held by the Office of Energy and Carbon Reduction and Academia Sinica. Our secondary data included annual reports and press releases from companies and the CNFI, together with articles from the gray literature (e.g., media articles, policy documents, research reports, and presentation materials) from third parties such as think tanks, government agencies, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). The data were analyzed to explore and identify the pathways of the carbon lock-in effect and the barriers to the introduction of an energy tax in Taiwan.

4. Analysis

This study analyzed the social and political dynamics of Taiwan’s three attempts to develop and promote energy taxation and discussed the path dependence that caused the failure of these plans. Although Taiwan has had three windows of opportunity to introduce an energy tax over the past 10 years or so, carbon lock-ins and high-carbon energy paths have continued to delay the implementation of a tax on energy. In light of this dynamic, this study explicated the structure of Taiwan’s high-carbon economy and the path dependence and carbon lock-in effect that exists within it to observe the way that these factors have blocked the implementation of a Taiwanese carbon tax system on each of the three occasions.

4.1. High-Carbon Regime

4.1.1. Raising the Curtain on Taiwan’s High-Carbon Economy

To understand the carbon lock-in effect in Taiwan, this study had to first inspect the carbon emission structures of the past 30 years. Internationally, the fact that the oil, steel, concrete, and transport industries are primarily responsible for high carbon emissions is widely understood. In Taiwan, the petrochemical industry has been responsible for driving the rapid increase in carbon emissions and making Taiwan a high-carbon economy.

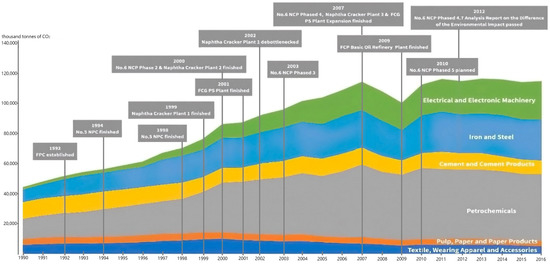

Figure 2 illustrates the distributions of carbon emissions from various industrial sectors in Taiwan between 1990 and 2016. A series of petrochemical facilities were established in the 1990s, including the Formosa Petrochemical Corporation (1992), the Naphtha Cracker Complex (NCC) V (1994), the NCC VI Phases I and II of the Formosa Petrochemical Corporation (1998–2000), and the firepower and cogeneration plants of Mai-Liao Power Phases I, II, and III (1997–2000), which increased the carbon emissions from the petrochemical industry. From 2001 to 2007, the NCC VI Phase VI, various light oil cracking plants, and steam–electricity cogeneration plants were successively implemented, which further increased the levels of carbon emissions and reached a peak in 2007. Correspondingly, the expansions of the NCC VI in Mai-Liao, Taiwan, during different periods caused carbon emissions to skyrocket [33]. The rapid expansion of the petrochemical industry in Taiwan, aided by private investments, has directly led to the prominent role of the petrochemical industry in high production levels of carbon emissions.

Figure 2.

The carbon emission trends in Taiwan during the 1990–2016 period by industrial sector. Source: made by authors.

Chou and Liou compared the carbon emission levels from the petrochemical industry between 1996 and 2007. They found clear evidence of the leading role that the petrochemical industry has played in the observed rapid increase in Taiwan’s industrial carbon emissions and, by extension, the increase in overall national carbon emission levels [33].

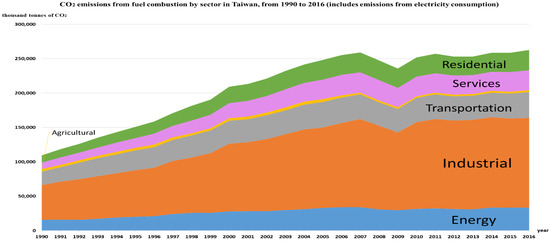

Figure 3 illustrates the overall trends in Taiwan’s carbon emissions between 1990 and 2016. From this figure, how the aforementioned drive to expand the petrochemical industry produced a proportional increase in carbon emissions can be seen. This growth in industrial sector emissions has pushed Taiwan’s overall carbon emissions into a continuously rising trend. In 1990, Taiwan’s overall CO2 emission levels were approximately 109.46 million tons, of which 46.13%, or 50.5 million tons, were produced by the industrial sector. By 2000, Taiwan’s CO2 emissions had already risen to 209.26 million tons, with the industrial sector producing 47.08%, or 98.52 million tons. By 2010, CO2 emissions had risen again to a total of 251.86 million tons, with the industrial sector producing 126.08 million tons, or 50.06% of the total. By 2016, the total emissions were 262.66 million tons, and the industrial sector’s contribution was 130.52 tons, or 49.69% [34,35].

Figure 3.

The overall CO2 emission trends in Taiwan during the 1990–2016 period. Source: made by authors.

4.1.2. The Carbon Lock-In Effect within Taiwan’s Brown Economy

The expansion of the petrochemical industry initiated Taiwan’s transition toward becoming a high-carbon economy. Taiwan’s economy has been locked onto a carbon-intensive industrial pathway since the early 1990s, and with this model of economic development, a simple analysis of path dependence would be insufficient to explain the growth of the brown economy. Instead, other potential factors need to be identified by examining the economic system, social and political awareness, and the technical aspects of carbon emissions to explore why and how the brown economy has developed.

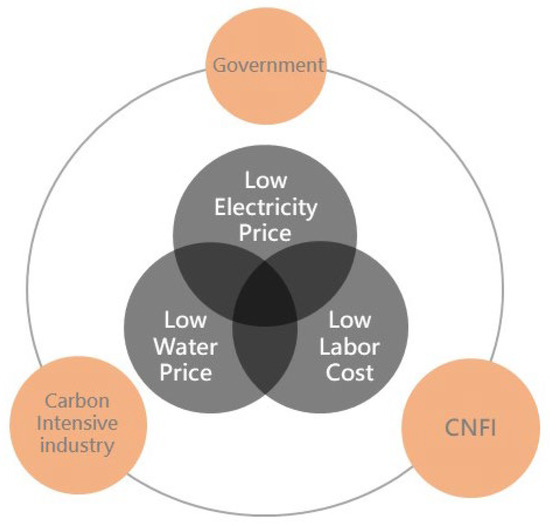

In terms of the economic system, electricity prices, water prices, labor costs, and petrol subsidies have sustained Taiwan’s brown economy. People’s perceptions of the economy have also played a powerful role. Since the CNFI declared that industries were facing five lacks and six losses, there has been an attempt to slow down the speed of the transition toward a low-carbon economy. Furthermore, carbon-intensive industries have become entangled with the nuclear industry to form the TIC, which helps to explain the technological lock-in within the Taiwanese context.

The Institutional Carbon Lock-In Effect

In 2006, Taiwan’s domestic household electricity rate was just USD 0.0783 per kilowatt, which was the lowest in the world. By 2015, it had increased to USD 0.09466 per kilowatt, which was still the fourth lowest in the world. The industrial rate in 2006 was USD 0.059 per kilowatt, which was the third lowest worldwide; however, by 2015, the industrial rates had risen to USD 0.092 per kilowatt, at which point Taiwanese industries had the 12th lowest costs worldwide [36]. In addition, following an international comparison of water prices, the NUS Consulting Group reported that Taiwan had the cheapest water in the world. In 2006, the cost of water in Taiwan was just NTD 8.25 (new Taiwanese dollars) per cubic meter. In comparison, Denmark, which had the highest water prices in the world that year, paid NTD 67.38 per cubic meter [37]. According to data on domestic water consumption in 160 cities that were released by the International Water Association in 2015, if every household used an average of 200 units of tap water annually, it would cost USD 86.58 in Taiwan, placing it tenth from the bottom in the price rankings [38].

According to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, Taiwan’s hourly compensation costs in manufacturing were USD 8.05 in 2006, which was the ninth lowest among industrial nations. Taiwan’s costs were significantly lower than those of other Asian nations. The average compensation in Singapore at that time was USD 13.77 per hour, whereas it was USD 17.55 in South Korea and USD 24.32 in Japan. If we make a similar comparison between Europe and the USA, we can see Taiwan’s labor compensation was a fraction of that in the USA (USD 30.49), the UK (USD 31.25 per hour), and Germany (USD 39.33). By 2015, Taiwan’s hourly compensation costs in manufacturing had risen to USD 9.49, which was the seventh lowest hourly compensation rate among industrialized countries. This figure continued to be low compared to other Asian countries. By 2016, Singapore and Japan had basic hourly rates of USD 16.01 per hour and USD 23.6 per hour, respectively, which represented a relative decline compared to the rates in South Korea, which had risen to USD 23.40. In comparison to Europe and the USA, the wage disparity grew even wider. By 2015, hourly wage rates were USD 35.02 per hour in the USA, USD 35.84 per hour in the UK, and USD 42.27 per hour in Germany [39]. Finally, in terms of fossil fuels, according to the IEA Fossil Fuel Subsidies Database 2010 survey, the Taiwanese government subsidized fuel oil, electricity, gas, and coal to a total of USD 648.6 million. In 2011, this figure reached a peak of USD 2097.7 million. Although these subsidies declined from 2011, they continued to be substantial, running as high as USD 310 million in 2017, USD 347.5 million in 2018, and USD 300 million in 2019.

It is safe to say that Taiwanese companies continue to enjoy a state that provides cheap electricity, cheap water, low labor costs, and long-term subsidies for fossil fuels. Taiwanese industries also gain significant profits from rent-seeking. This structure of development is often referred to as a “brown package”. Martinez-Covarrubias [40] referred to this as a brown economy or high-carbon economy. A brown economy is defined by high carbon emissions, the predominance of high-energy consumption industries, cheap energy (both electricity and water), cheap labor, and fossil fuel subsidies that force the environmental costs of industry to be externalized.

Friedmann, Fan, and Tang [41] identified several carbon-intensive industries within the general industrial sector. These included the steel, fossil fuel, chemical, and cement industries. These industries are part of the global trade commodity category, and during any transitions toward low-carbon economic models, they face the challenge of international price competition. Such fears help to explain why these industries have frequently focused on keeping energy prices low, keeping labor costs down, and reducing the burdens of environmental regulations. In this respect, Taiwan’s brown economy and industries are typical of brown economies observed elsewhere.

The Cognitive Aspect of the Carbon Lock-In Effect

The Chinese National Federation of Industries (CNFI) represents the central organizing force behind the lobbying by Taiwan’s carbon-intensive industries. In its 2008 White Paper, the CNFI [42] began lobbying the Taiwanese government to keep electricity prices, water prices, and labor costs down. Low costs were viewed as critical to continued industrial development. As part of its efforts, the CNFI repeatedly attempted to influence public discourse and, in turn, policy as a whole. In the 2015 CNFI White Paper [43], the political discourse around the so-called “five lacks” (i.e., the lack of water, electricity, labor, land, and people) constituted a clear defense of the brown economy. The White Paper described the five lacks in almost existential terms: “Taiwan’s overall investment environment is rapidly moving toward complete collapse. In terms of the future of our domestic economy, we are currently in an environment lacking in water, electricity, labor, land and qualified personnel … In the face of a domestic government that is all but incapacitated, a society out of control, a congress derelict of duty, an economy out of balance, a lost generation and a nation that has lost its overall objective; in the past we have always appealed to ‘God save Taiwan’ rhetoric, today many companies have no choice but to say ‘goodbye to Taiwan’”. Moreover, in the 2016 White Paper, the CNFI [44] again emphasized the five lacks: “We sense the rapid deterioration of conditions in Taiwan’s overall investment environment, with the main reason being that in the fierce global competition, we are facing the dilemma of ‘five lacks’, ‘sick losses’, bringing private investment to a standstill and causing Taiwan’s long-term economic growth to grow stagnant”.

The use of the so-called “five lacks” perspective by the CNFI to lobby for the continued development of the brown economy is evident (Figure 4). This discourse around the brown economic complex has fundamentally locked Taiwan’s economic development onto its current developmental path and has exposed Taiwan to criticism, with many pointing out that such a position is not beneficial to socio-economic transitions. Sun [45] argued that the prices of all factors of production are far too low and criticized the “seven lows”, namely low water, electricity, and oil prices and low material costs, interest rates, exchange rates, and labor costs. Furthermore, these cheap production factors have not made Taiwan’s industries more competitive, mainly because companies lack efficiency as a whole.

Figure 4.

The brown economy complex in Taiwan during the 1990–2016 period. Source: made by authors.

In 2017, the CDP [46] gave Taiwan’s main energy-consuming industries, such as the China Petrochemical Company (CPC), Formosa Chemicals and Fiber Corporation (FCFC), and Taiwan Plastics (TP), a level C rating, which indicated that their energy consumption levels were too high. The Taiwan Environmental Protection Union also strongly criticized the CNFI’s “five lacks” strategy as a “fake” issue. The Union also argued that the government should avoid abusing its monopoly on data to avoid improper profiteering [35].

The Carbon Lock-In Effect of the TIC Complex

In addition to its systems and cognitive aspects, the brown economy’s path dependence also entrains technology, thereby reinforcing the TIC and carbon lock-in effect. This can be observed from two perspectives: the increase in direct investments in carbon-intensive fossil fuels and claims by carbon-intensive industries that they provide electricity supplies at low costs from stable nuclear energy generators.

Taiwan’s GHG emissions are mainly the result of CO2 released from fossil fuels. Carbon dioxide accounts for 90% of Taiwan’s overall emissions, with industrial sectors (including indirect emissions) producing close to 60%. The steel, petroleum, oil refining, and semiconductor industries are the major emitters (Figure 2 and Figure 3). Specifically, Taiwan began to open up its power industry to independent power producers (IPPs) in 1995. Of the two private coal-burning power plants that are currently running in Taiwan, one receives most of its investments from carbon-intensive industries, including the Formosa Plastics and the Taiwan Cement Corporation, with holding ratios of 100% (Formosa Plastics Group: Mai-Liao Power Plant) and 70% (Taiwan Cement: He-Ping Power Plant). Table 1 and Table 2 outline the contributions from these investors to Taiwan’s overall GHG emissions, as well as the ratio between the overall power generated and the GHGs emitted by the thermal power plants. Investments in coal-burning power plants and opening up Taiwan’s energy generation sector to IPPs once again consolidated Taiwan’s nuclear–coal complex as a source of cheap energy and equally strengthened the carbon lock-in effect.

Table 1.

Taiwan’s IPP investors and their overall contributions to national GHG emissions.

Table 2.

The power generation and GHG emission contributions from Taiwan’s IPP investors.

In practice, the total emissions from Formosa Plastics reached 55.15 million tons in 2015, accounting for 21.3% of the national GHG emissions. The group’s largest investment was in the Mai-Liao Power Plant, which generated 8% of Taiwan’s thermally generated power in 2015 and accounted for 10.82% of the national emissions. The Taiwan Cement Company accounted for 2.03% of the national GHG emissions in 2015, while the He-Ping Power Plant produced 5.44% of power and 7.15% of emissions in the same year.

At present, the goal of replacing traditional power generation with renewable energy continues to face many challenges, both in terms of technology and costs. In 2012, the nuclear energy base load debate grew stronger. The CNFI [47] stated, “Energy policy should see nuclear energy security as the best way of ensuring a low-carbon environment while recognizing the problems that an insufficient amount of domestic home-grown energy can have there is a need to continue to promote base load generating set, to ensure power generation and electricity price stability”.

A 2013 comparison of the nuclear energy ratios of Taiwan and South Korea contained the recommendation to rebuild Nuclear Power Plant Four [47], “In light of international competition, South Korea’s nuclear energy, which accounts for 34% of the country’s energy produced, makes its electricity costs significantly lower than Taiwan, moreover the continued controversy around the rebuilding of Nuclear Power Plant Four, has left Taiwan’s industries facing a situation where electricity costs are far from beneficial”. These recommendations were extended in 2014, when it was “suggested that the plan to extend the use of Nuclear Power Plants One, Two and Three be brought forward, in order to lower the risk of facing a lack of electricity”.

These proposals to reconstruct or extend the lives of nuclear plants coincided with the state-owned Taiwan Power Company’s declaration of support for nuclear energy. Before the Taiwanese government made its 2017 amendments to the Electricity Act, which encouraged private investments in renewable energy, numerous IPPs operated within the Taiwanese energy sector. In addition to the two aforementioned investors in private coal-burning plants, there were seven other IPPs that were LNG power-generating companies of the parent primary investor TaiPower. Therefore, it is safe to say that the state-run TaiPower had an almost complete monopoly over Taiwan’s electricity system. Within the context of Taiwan’s unique international standing, Taiwan initiated a collaboration between nuclear engineers, industry, government officials, and academics in the 1960s, who went on to work together between 1973 and 1985 to establish Nuclear Power Plants One, Two, and Three as commercial ventures. During the mid-1980s, plans for Nuclear Power Plant Four were also drawn up.

Tung [48] analyzed the dominance of this industry–bureaucracy–academic nexus within the scientific discourse around nuclear energy. In particular, he critically examined their attempts to convince the public that nuclear energy is safe and necessary in the face of insufficient electricity supplies and demands for cleaner forms of energy. At the same time, the Taiwanese government claimed that the construction of large-scale nuclear systems complied with the national development policy, which intended to provide low-cost electricity to energy-intensive industries.

In 2000, the newly elected Democratic Progressive Party began calling for the repeal of plans for the construction of Nuclear Power Plant Four. Nevertheless, the pro-nuclear rhetoric from the technocratic–nuclear complex continued to influence public discourse. This, along with persistent lobbying by the carbon-intensive industrial sector, produced a fierce political conflict that thwarted the plans for Nuclear Power Plant Four.

During this period, the brute force of the brown economy exerted itself on Taiwanese society. In cooperation with large-scale nuclear power technical systems, carbon-intensive industries used stable power supplies, low electricity costs, and the call for continued economic growth to tie up Taiwan’s energy policy. In reality, Taiwan’s electricity prices continued to be low in comparison to those in other countries, and those low prices fed back into continued support for the brown economy. In turn, the brown economy continued to thwart attempts to move forward with carbon taxation.

4.2. Three Lost Windows of Opportunity

4.2.1. Three Windows of Opportunity

Beginning in 1998, policies aiming to achieve a low-carbon economic transition have been on the agenda in Taiwan on several occasions. The ongoing debate about the promotion of energy taxation as a means to internalize the costs of high carbon emissions has since never been absent from the Taiwanese government. There have been three major windows of opportunity to bring a carbon tax into law in Taiwan (Figure 5). This study analyzed how these opportunities arose, how they played out in the political discourse of the time, and how they eventually became failed opportunities.

Figure 5.

The three windows of opportunity for introducing a carbon tax in Taiwan. Source: made by authors.

First Window of Opportunity: Taiwan’s First Move to Draft Energy Taxation Legislation (1998–2006)

The first substantial discussion about carbon taxation in Taiwan took place in 1998 at the first National Energy Conference. At this conference, the majority of delegates supported the institution of a taxation system to manage carbon emissions. In 2004, over half of the attendees at the Environmental Consensus Conference also supported a carbon tax, yet these resolutions ended up being nothing but empty words in the end [49,50,51,52,53,54,55].

In 2006, the release of Gore’s An Inconvenient Truth prompted a widespread awakening of the Taiwanese public to environmental issues. The legislator (Focus Group 1 No.2, F1#2) indicated that “The legitimacy of the energy tax meant it was suggested very early on at that time, public surveys showed large support for such a tax, as the public had already become aware of the threat that GHGs possessed. At this time, everyone’s understanding had already been established so legitimacy was strong”.

Another interviewee from an environmental NGO (F2#8) stated that “Political opportunities can be separated into the political atmosphere domestically and internationally. In 2006, the release of An Inconvenient Truth showing the reality of the issue, formed both domestic and international pressure; as a result, Taiwan’s discussions on related energy tax reached its peak during this period”.

During this period of domestic and international pressure, six different drafts of an energy tax bill were proposed by different parties. One of these was a draft legislation by legislator Chen Ming-Zhen, which was supported by 131 members of Congress, representing 60% of the legislators across all parties.

Therefore, at the congressional level, the idea of energy taxation already possessed a high level of social legitimacy, and there appeared to be a high probability that the bill would be finalized. However, political will had to be present, as identified by one interviewee (F1#2), “If the administrative agency doesn’t have the determination or will to follow through, in the end nothing can go forward”.

In 2006, the government even made a resolution at the “Taiwan Economy Sustainable Development Meeting”, which supported parliament in proposing an energy tax bill and proposed the progressive integration of the existing fuel taxation system. The resolution also asked the Ministry of Economic Affairs and the Ministry of Finance to propose a package of complementary economic policies in support of an energy tax [56,57]. As a result, the Ministry of Finance introduced the Energy Tax Bill and planned to enter it into force in 2007. This proposal also included a nine-year plan for its implementation. However, it eventually failed [58].

The failure of the Energy Tax Bill suggested that although Taiwanese society was aware of the significance of climate change, international pressure was not yet strong enough to produce a societal push for climate action. This lack of pressure undermined the view that an energy tax was vital.

Interviewees also believed that the failure to achieve systemic energy reforms was driven by opposition from the economic bureaucracy. The ruling party at that time appointed two consecutive chairmen to the Council for Economic Planning and Development. Both chairmen believed that energy taxation would hamper international competition and refused to pass an energy tax bill (F1#1,5). Eventually, their opposition forced the Ministry of Finance to postpone action and change its position on the bill, claiming that the time was not right to introduce such a tax [59,60].

While the economic bureaucracy worried about international competition and the administrative agency lacked determination, industry opposed an energy tax because of doubts over its potential economic impact. The CNFI published articles that opposed an energy tax in its industry magazine in September 2006 [61]. In 2008, the CNFI once again released its White Paper and reiterated its concerns about increasing financial burdens and the impact of energy taxation on international competition. Carbon-intensive petrochemical, steel, and cement industries, including Formosa Plastics, mounted the fiercest opposition to energy taxation [42,62]. These industries had been core members of the CNFI for a very long time and helped to trap Taiwan into its brown economy complex, which impeded the country’s ability to transition toward a decarbonized future (F2#8,9).

Second Window of Opportunity: Tax Reformation Period (2007–2014)

Following the failure of the first attempt to introduce an energy tax bill in 2006, the issue was raised again in the 2008 Taiwan election. Both presidential candidates raised the issue of energy taxation as a key ingredient for initiating the transition to a low-carbon society. When Kuomintang (KMT) came to power, the president vowed to promote energy taxation and, in doing so, opened the second window of opportunity, which included the following resolution from the 2008 National Science Council Committee Meeting: “Levying Energy Tax and Carbon Emissions Trading” [63]. At the third National Energy Conference in 2009, the framing of an energy bill was officially debated. It was proposed that the bill should be compatible with the four energy acts (i.e., the Energy Administration Act, the Renewable Energy Development Act, the GHG Reduction Act, and the Energy Tax Bill). The debate focused on the Energy Tax Bill as a reflection of the external costs of energy. It even became a policy agenda issue for the Taxation Reform Commission of the Ministry of Finance, with plans to promote the Energy Tax Bill [64,65]. On the 19th of October 2009, the Taxation Reform Commission resolved to implement reforms to move toward an integrated green taxation system. Their proposals targeted eight forms of fossil fuels, including petrol, diesel oil, kerosene, aviation fuel, natural gas, liquefied petroleum gas, fuel oil, and coal. In 2010, the Energy Taxation and GHG Environmental Tax Act was drawn up with the intention of implementing gradual adjustments to energy tariffs over the following 10 years. A total of NTD 403.7 billion would be collected from such taxation, and GHG emissions would be reduced by 46.047 million tons. In addition to the fact that green taxation would hold polluters accountable by making them pay financially, low-income household subsidies, public transport subsidies, and investments in low-carbon R&D would ensure a spirit of neutrality in finance and taxation, thereby yielding multiple dividends and social equity [50,64].

Thus, a political opportunity and the possibility of establishing an energy taxation system were developed. One interviewee stated that “there was an opportunity, and we weren’t far from being successful”. However, the CNFI moved strongly to raise political opposition and even made a statement to the Ministry of Economic Affairs that emphasized the impacts of the energy tax bill on the GDP and employment, speculating that the tax would result in a 2.93% drop in the GDP as a whole, a 7.95% decrease in the value of manufacturing, and 200,000 jobs being lost in the textile industry. The CNFI also highlighted the increasing burdens that would be felt by energy-intensive industries, which were considered to be vital to the Taiwanese economy and would, according to the CNFI, relocate their businesses. Therefore, the CNFI insisted on postponing the introduction of an energy tax [65,66,67]. Even after the KMT took office, institutional and cognitive lock-ins continued to block an energy tax bill from being passed. The economic mindset of the government was augmented by lobbying from the TIC. These forces conspired to block the introduction of an energy tax bill. Even though the president of Taiwan promised an energy tax during the election, which was endorsed by the premier of the Executive Yuan, the Minister of Finance (who was also the vice premier of the Executive Yuan) urged the government to delay any developments. Eventually, the combined political, bureaucratic, and industry opposition caused the second window of opportunity to fail (F1#1, F2#10).

The lack of action by the administrative bureaucracy was also key to this policy failure. One interviewee pointed out that although the Ministry of Finance nominally supported legislation to reduce carbon emissions and increase energy efficiency, they expected a professionally competent agency to deal with the details. Thus, the GHG Reduction Act should have been handled by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Energy Affairs, or the Ministry of Economic Affairs Bureau of Energy, thereby allowing various professionally competent units to handle the formal control of fees. One interviewee (F1#5) stated that “Simply put, the Ministry of Finance didn’t consider this to be an issue that was within their scope of responsibility”. Furthermore, in 2008, the CNFI White Paper consistently emphasized the “five lacks” concept and continued to promote the brown economy, which became the dominant framework for national development. The CNFI demanded that the government be cautious in any plans for an energy taxation system (F1#3, F2#6).

Third Window of Opportunity: The Greenhouse Gas Reduction and Management Act (2015–2020)

In 2014, the Atomic Energy Council and the Ministry of Science and Technology released separate research reports on energy taxation [68,69]. Energy taxation was also on the agenda of the fourth National Energy Conference in 2015. The conference concluded that before introducing an energy tax, the government should first introduce a carbon fee, the revenues from which could be used specifically to enhance industrial emissions performance. This conclusion opened up the discussion around the introduction of a carbon tax and levy system into the GHG Reduction and Management Act Bill [70,71].

The planning for a third attempt to introduce a carbon tax came to a head in 2015, just as the UNFCCC COP21 meeting adopted the Paris Agreement. As international pressure to reduce emissions mounted, the Taiwanese government drew up the GHG Reduction and Management Act. The clear specification of a green taxation mechanism in the draft text represented the opening of the third window of opportunity for action.

Article 5, paragraph 3, Subparagraph 3 of the proposed act stated that the government should tax imported fossil fuels based on their carbon dioxide equivalence. The goal of this measure was to respond to the impact of climate change and comply with the principles of equity and social welfare promotion.

By that time, industry groups had changed their views on energy taxation. For instance, the textile giant Everest Textile Co. fully agreed with a carbon tax and urged the industry itself to find a way to save energy and electricity. It also emphasized that a carbon tax would encourage the industry to upgrade its infrastructure and increase its international competitiveness [72]. However, carbon-intensive industries and the CNFI continued to oppose such progress. The CNFI chairman Lien-Shegn Tsai emphasized that the costs of energy taxation or carbon fees would shift from industry to consumers. He also opposed the idea of treating the cheap industrial electricity fee as a subsidy. Furthermore, the Petrochemical Industry Association of Taiwan and the Taiwan Steel and Iron Industries Association suggested that their industries had already actively complied with climate policies. They claimed that if the government were to impose more environmental fees on industry, such as an air pollutant fee, soil and groundwater pollution remediation fee, or even a carbon fee, it would burden industry too much [73].

However, the aforementioned clause was merely declarative and became delayed by both the government and carbon-intensive industries. The government has never enforced this clause. In fact, in 2012, the Taiwanese EPA was influenced by a legal decision made in Massachusetts against the EPA, which determined that GHGs are air pollutants under the Clean Air Act. As a result, the EPA incorporated GHGs into Taiwan’s Air Pollution Control Act. Although redefining GHGs as pollutants and adopting an air pollution control fee would enable GHGs to be brought under control, the main purpose of the Taiwan EPA was not to internalize the costs of CO2 but to build a legal basis for GHG emissions inventory.

Industrial opposition to carbon taxation, including the reclassification of GHGs as pollutants, was quite vigorous. Even when the GHG Reduction and Management Act was pushed through in response to the Paris Agreement, the final shape of the act was a compromised product for both government and industry. The interviewee (F2#9) pointed out, “At the time, the original GHG Reduction and Management Act had already been delayed by more than a decade of discussions. Finally, the EPA declared that if the law failed to pass, they would implement controls over GHGs under the Air Pollution Control Act”.

Since air pollution controls were inevitable, the high-carbon industries and their representatives reasoned they should attempt to negotiate the contents of the GHG Reduction and Management Act, which was still under revision. The industries attempted to influence every word of the act and fought strenuously for favorable conditions (F1#3, F2#6). The industry lobbying strategy, which temporarily introduced a declarative clause, once again delayed the enforcement of a carbon tax. Without any other pressure from the markets, such as CBAM, a carbon tax could not be introduced in Taiwan.

Even though Taiwan faced great international pressure after COP21, it proved hard to shake off the influence of the TIC, which firmly backed the high-carbon regime and delayed the implementation of a carbon tax once again.

4.2.2. Lack of Pressure from Social Movements

Since the mid-1980s, various social movements against the chemical and petrochemical industries have continued to occur in Taiwan, and these environmental movements have been directly or indirectly related to climate governance in form and connotation. Chou [2] divided these movements into anti-pollution and climate change risk movements. The former are related to residents who fight for their health, and most of them are regional movements, although a few have also become national movements, and their efforts are concentrated on reducing pollution. The latter are exemplified by the anti-Binnan Petrochemical and Steel cases in 1995, the anti-Kuokuang Petrochemical Project case in 2010, and the anti-NCC VI expansion in 2011. Their protest appeals oppose high energy consumption, high carbon emissions, high water consumption, and high pollution levels, and they fight with fairly systemic knowledge. Such social movements have also continued to increase public awareness of the risks of climate change.

However, these environmental movements directly fight against major development projects, and even if they involve climate change risks and raise public concerns about carbon emissions and energy consumption, the focus of the struggle often ceases with the end of the event, i.e., an institutional energy tax cannot promote large-scale social movements but can shape political opportunities for structural mobilization [74] and change the system.

An interviewee from a northern NGO (F2#8) stated that “What can most attract everyone’s attention in Taiwan’s environmental movement is the case so that everyone can focus on there, so you can also think of it as a political opportunity, which will cause social discussion and become a social issue, all of which will be discussed at that time. In fact, the foundation of environmental groups and civil society in Taiwan is still relatively weak. In addition to individual struggles, the group’s strength in promoting long-term change is insufficient”.

In addition to the lack of political mobilization opportunities for social movements, societal understanding, discussion, and consensus on systemic energy taxation are quite lacking. Another interview from NGO (F2#9) stressed that “Although society has a consensus on addressing warming, an understanding of the necessity of using pricing tools, such as carbon tax, to solve the problem is lacking, and the connection is not so direct, which, in turn, affects many policies”. Another interviewee (F2#8) stated that “Public discussions need some design, and the government also needs to have a role in the discussion. Through the understanding of the problem, high-density activities are held so that social groups can start discussions”.

Although social movements from outside the system have created spaces for society to discuss carbon taxation, they have failed to trigger strong social movements that call for the governmental implementation of a carbon taxation system. Therefore, the high-carbon economic structure that is difficult to break, coupled with the lack of public power accumulated outside the system that directs the focus of public attention and continues to put pressure on the government, can often only return to the system to carry out reforms that seek institutional improvements within the system. When the push for change can only return to the system to dismantle the structure and system, these opportunities are likely to be gradually lost within the existing bureaucratic structure and the lobbying of high-carbon interest groups.

After the success of the Anti-Kuokuang Petrochemical Movement in April 2011, the anti-PM2.5 issue derived from the movement continued to ferment, and the Changhua Medical Alliance that was established by the movement continued to expand the network to include air pollution and health [2]. This resulted in a clear understanding and large amounts of attention among the Taiwanese people on the PM 2.5 issue and prompted the Environmental Protection Agency to formulate PM-related control standards in accordance with World Health Organization specifications at the end of 2013 and increase regulations.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

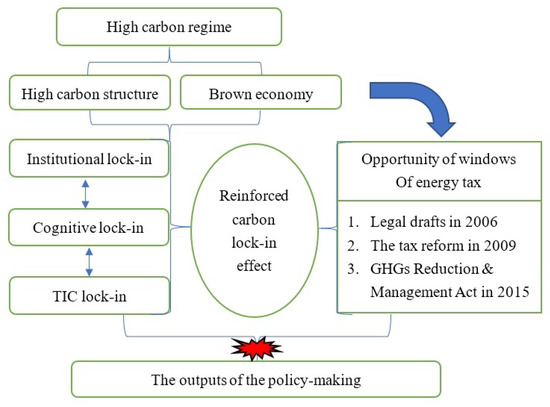

Our analysis highlighted Taiwan’s long-term path dependence on its high-carbon regime, which includes high-carbon infrastructures and a brown economy. This path dependence ensures that the Taiwanese economy and society remain locked onto their existing development tracks. This regime is quite complicated and produces entangled relationships between the economic bureaucracy and industry. The state, carbon-intensive industries, and the CNFI co-established the brown economy complex and have entrenched institutional, cognitive, and technological carbon lock-ins. In this sense, the system of production factors is full of reasonable discourse around low electricity, water, and labor prices and subsidies. In terms of economic development, the “five lacks” have become the common language of the CNFI, industry, and the economic bureaucracy. Overall, the TIC is heavily involved in energy and economic policies.

This carbon lock-in effect has blocked the sustainable transformation of Taiwan’s economy to some extent. Under the influence of international climate conventions, proposals from the Taiwanese Parliament and Ministry of Finance, green tax reforms, and the GHG Reduction and Management Act, three windows for the establishment of energy taxation opened. However, during each window of opportunity, the conservatism of the economic and fiscal bureaucracy, which was hesitant to pursue policies, and inconsistent stances on energy taxation ensured that Taiwan continued to be enmeshed in its brown economy. Carbon-intensive industries and the CNFI engaged in high-profile lobbying against energy taxation. They also mobilized their internal political and economic networks to block energy taxation on the grounds that it would damage Taiwanese industrial competitiveness.

The cases of Norway and OECD countries have confirmed that manufacturing industries can have considerable lobbying power within manufacturing-dependent economies that have high carbon emissions. When this influence is linked to a brown economy with low electricity and water prices, low wages, and a powerful TIC dominated by nuclear and coal power, the carbon lock-in effect is reinforced (Figure 6). This kind of entrenched carbon lock-in effect, where political actors and bureaucrats are enmeshed with powerful industries, is seen in Taiwan.

Figure 6.

The reinforced carbon lock-in effect in Taiwanese carbon taxation legislation. Source: made by authors.

Meanwhile, the prioritization of economic development among other East Asian nations should not be neglected. High-carbon emission countries, such as Japan and South Korea, also have powerful industrial coalitions and nuclear energy complexes that impede their ability to pursue low-carbon transitions. As in Taiwan, governmental decision-making tends to cater to the needs of industry. Even though Japan and South Korea established carbon taxation in 2012 and carbon trading in 2015, they have still been criticized for failing to establish environmental and social justice policies and for lacking mechanisms to make bottom-up democratic environmental decisions. Because of the brown economy and the reinforced carbon lock-in effect, the three opportunity windows for implementing energy taxation failed in Taiwan.

Our research retrospectively analyzed the structural path dependence and other difficulties that were faced during Taiwan’s attempted transitions toward a low-carbon economy. In combination with the common issues among developmental states, the technocratic decision-making in East Asia and the high-carbon industries have shaped the carbon lock-in effect to a certain degree. Additionally, the case of Taiwan illustrates how long-term low energy prices and wages are structured. Our study analysis showed that a brown economy reinforces the carbon lock-in effect and delays low-carbon transitions, resulting in the stagnation of attempts for sustainable economic transformation. Unless major external forces that are sufficient to break the deadlock are introduced, genuine low-carbon reforms seem unlikely.

Seto et al. pointed out that to break free of the technological and infrastructure lock-ins and create a window of opportunity, significant short-term measures and investments are required while maintaining policy and investment flexibility [8]. According to the Bureau of Energy in Taiwan [75], the Taiwanese manufacturing industry produced approximately 51.14% of the total GHG emissions in 2020, and its electricity consumption reached 57%. Hence, one key to changing the high-carbon structure in terms of technology is to exclude fossil fuel-based power generation. The Taiwanese government has vigorously promoted energy transformation since 2016 and is planning for 20% of total power generation to be produced by green energy by 2025. It has also vowed to continue to increase wind and solar energy generation year by year.

In terms of exogenous shocks, Seto et al. and Aklin et al. suggested that, according to international and domestic conditions and environments, forcing the regime to break away from its original path dependence and move toward a positive direction of development is possible [4,8]. In addition to following global trends and speeding up investment in and the construction of an energy transition, the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM), which the EU is due to test in 2023, could also force and drive Taiwan, an export-oriented country, to discuss and institutionalize carbon taxation. Accordingly, in the 2021 annual policy proposal from the CNFI, which represents the manufacturing industry, there was an unprecedented push for the government to speed up carbon taxation implementation so that industries in Taiwan can meet international development trends and become competitive [76]. Furthermore, the draft for the Climate Change Adaptive Law that was proposed by the Taiwan Environmental Protection Association at the end of 2021 stipulates a carbon levy that aims to meet the global net zero transition.

These global governance and technological changes that have led to market and economic transformations have also created a new window of opportunity and begun to reverse Taiwan’s reinforced high-carbon regime and society. Under this framework, this study could be quite significant. On the one hand, we demonstrated the path dependence caused by the high-carbon emission structure and the brown economy and highlighted the structural problem of the carbon lock-in effect.

Many rapidly industrializing/industrialized countries around the world exhibit similar political and economic dynamics to those in Taiwan. Their carbon emissions are increasing and are tied to large and growing manufacturing sectors, low wages, and low environmental and energy costs. These countries often suffer from chronic social inequity and lack bottom-up scientific and democratic decision-making. The combination of a high-carbon regime and a brown economy consolidates the carbon lock-in effect. The result is that attempts for sustainable transformations in rapidly industrializing countries become mired in complex political and economic conflicts and suffer from severe hysteresis, which is detrimental to global carbon reduction processes and goals.

On the other hand, if exogenous shocks and flexible endogenous policies and investments can be created through the analysis of these structural constraints, then driving Taiwan to eliminate its brown economy and carbon lock-in effect and gradually transition toward a low-carbon economy is possible. The current global trend of working toward net zero carbon emissions, CBAM, and energy transitions is providing such conditions; however, the situation depends on the actual conditions and development within each country.

This study contextually examined Taiwan’s three windows of opportunity for energy taxation implementation. Although we closely analyzed the relevant policies, documents, and draft legislations and conducted key focus groups and in-depth interviews with various stakeholders, including officers, scholars, industrial representatives, and NGO workers, our analysis of policy and political conflicts at each stage still had certain restrictions. Specifically, we conducted a qualitative policy analysis rather than a quantitative analysis, which could have been influenced by statistical data [77,78]. Nevertheless, the aim of this study was to start a discussion between developing states and high-carbon regimes to expose the plight of brown economic systems in the face of the requirements for rapid global low-carbon transformation and propose possible breakthrough opportunities that could be used as examples and bases for future research in various countries around the world.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.-T.C.; methodology, K.-T.C.; validation, K.-T.C. and H.-M.L.; writing—original draft preparation, K.-T.C.; writing—review and editing, K.-T.C. and H.-M.L.; visualization, K.-T.C. and H.-M.L., supervision, K.-T.C.; project administration, K.-T.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

Data available on request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of internet.

Appendix A

Table A1.

Details of interviews (focus group) *.

Table A1.

Details of interviews (focus group) *.

| Organization | No. of Respondents | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Government organization | ||

| Environmental Protection Administration, R.O.C. | 1 | 24 June 2020 |

| 1 | ||

| 1 | ||

| National Development Council | 1 | 29 July 2021 |

| Ministry of Finance, R.O.C. | 1 | 24 August 2021 |

| Ministry of Economic Affairs, R.O.C. | 2 | 24 August 2021 |

| Legislative Department | ||

| Legislator | 2 | 24 June 2020 |

| 2 | 29 July 2021 | |

| Legislator’s office | 1 | 3 July 2020 |

| Industry organizations | ||

| Chinese National Federation of Industries | 1 | 24 June 2020 |

| 1 | 29 July 2021 | |

| Chinese Petroleum Institute | 1 | 29 July 2021 |

| China Steel Corporation | 1 | 24 August 2021 |

| CPC Corporation, Taiwan | 1 | 24 August 2021 |

| Taipei Computer Association | 1 | 24 August 2021 |

| Research institutions (NGO/University/Think tanks) | ||

| Green Citizens’ Action Alliance | 1 | 24 June 2020 |

| 1 | 23 September 2021 | |

| Taiwan Youth Climate Coalition | 1 | 24 August 2021 |

| Greenpeace | 1 | 23 September 2021 |

| Citizen of the Earth, Taiwan | 1 | 3 July 2020 |

| 1 | 23 September 2021 | |

| National Taipei University of Business | 1 | 24 June 2020 |

| 1 | 23 September 2021 | |

| National Taipei University | 1 | 23 September 2021 |

| Academia Sinica | 1 | 24 June 2020 |

| 1 | 23 September 2021 | |

| Total | 29 |

* Note: To protect the anonymity of focus group respondents, interview codes arranged throughout the findings do not correspond with the order of this list.

References

- World Bank. State and Trends of Carbon Pricing Mechanism. 2020. Available online: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/33809 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Chou, K.T. Sociology of Climate Change: High Carbon Society and Its Transformation Challenge; National Taiwan University Press: Taipei, Taiwan, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- International Energy Agency. CO2 Emissions from Fuel Combustion. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/energy/co2-emissions-from-fuel-combustion-2019_2a701673-en (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Aklin, M.; Urpelainen, J. Political competition, path dependence, and the strategy of sustainable energy transitions. AJPS 2013, 57, 643–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voß, J.P.; Kemp, R.; Bauknecht, D. Reflexive Governance: A View on an Emerging Path. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 419–437. [Google Scholar]

- Rip, A. A co-evolutionary approach to reflexive governance—And its ironies. In Reflexive Governance for Sustainable Development; Elgar: Cheltenham, UK, 2006; pp. 82–100. [Google Scholar]

- Unruh, G.C. Understanding carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 817–830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seto, K.C.; Davis, S.J.; Mitchell, R.B.; Stokes, E.C.; Unruh, G.; Ürge-Vorsatz, D. Carbon lock-in: Types, causes, and policy implications. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 2016, 41, 425–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, P.; Creutzig, F.; Ehlers, M.H.; Friedrichsen, N.; Heuson, C.; Hirth, L.; Pietzcker, R. Carbon lock-out: Advancing renewable energy policy in Europe. Energies 2012, 5, 323–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unruh, G.C. Escaping carbon lock-in. Energy Policy 2002, 30, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aghion, P.; Hepburn, C.; Teytelboym, A.; Zenghelis, D. Path Dependence, Innovation and the Economics of Climate Change. Policy Paper. 2014. Available online: https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/publication/path-dependence-innovation-and-the-economics-of-climate-change/ (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Pierson, P. Increasing returns, path dependence, and the study of politics. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2000, 94, 251–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotmans, J.; Loorbach, D. Towards a Better Understanding of Transitions and Their Governance: A Systemic and Reflexive Approach. In Transitions to Sustainable Development: New Directions in the Study of Long-Term Transformative Change; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 105–199. [Google Scholar]

- Kasa, S. Policy networks as barriers to green tax reform: The case of CO2-taxes in Norway. Environ. Politics 2000, 9, 104–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svendsen, G.T.; Daugbjerg, C.; Hjøllund, L.; Pedersen, A.B. Consumers, industrialists and the political economy of green taxation: CO2 taxation in OECD. Energy Policy 2001, 29, 489–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klenert, D.; Mattauch, L.; Combet, E.; Edenhofer, O.; Hepburn, C.; Rafaty, R.; Stern, N. Making carbon pricing work for citizens. Nat. Clim. Change 2018, 8, 669–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, T.; Rudolph, S.; Lee, S. The Japanese carbon tax and the challenges to low-carbon policy cooperation in east Asia. In Tax Law and the Environment: A Multidisciplinary and Worldwide Perspective; Lexington Books: Littlefield, TX, USA, 2018; pp. 85–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, E.S. The politics of climate change policy design in Korea. Environ. Politics 2016, 25, 454–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dent, C.M. Renewable Energy in East Asia: Towards a New Developmentalism; Routledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Dent, C.M. East Asia’s new developmentalism: State capacity, climate change and low-carbon development. Third World Q 2018, 39, 1191–1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.Y.; Thurbon, E. Developmental environmentalism: Explaining South Korea’s ambitious pursuit of green growth. PAS 2015, 43, 213–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kameyama, Y. Climate Change Policy in Japan: From the 1980s to 2015; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Proposal on Japan’s Long-Term Growth Strategy under the Paris Agreement. 2019. Available online: https://www.keidanren.or.jp/en/policy/2019/022.html (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Hasegawa, T.; Fujimori, S.; Takahashi, K.; Masui, T. Scenarios for the risk of hunger in the twenty-first century using Shared Socioeconomic Pathways. Environ. Res. Lett. 2015, 10, 014010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasegawa, K. Continuities and discontinuities of Japan’s political activism before and after the Fukushima disaster. In Social Movements and Political Activism in Contemporary Japan; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 115–136. [Google Scholar]

- Sugiman, T. Lessons learned from the 2011 debacle of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Public Underst. Sci. 2014, 23, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldrich, D.P. Rethinking civil society–state relations in Japan after the Fukushima accident. Polity 2013, 45, 249–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kingston, J. After 3.11: Imposing Nuclear Energy on a Skeptical Japanese Public 3.11. 2014. Available online: https://apjjf.org/2014/11/23/Jeff-Kingston/4129/article.html (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- Matsumoto, M. “Structural disaster” long before Fukushima: A hidden accident. Dev. Soc. 2013, 42, 165–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funabashi, H. Why the Fukushima nuclear disaster is a man-made calamity. Int. J. Jpn. Sociol. 2012, 21, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ku, D. The anti-nuclear movement and ecological democracy in South Korea. In Energy Transition in East Asia: A Social Science Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2017; pp. 28–44. [Google Scholar]

- Chou, K.T. Tri-helix energy transition in Taiwan. Energy Transition. In Energy Transition in East Asia: A Social Science Perspective; Routledge: London, UK, 2018; pp. 34–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chou, K.T.; Liou, H.M. Analysis on energy intensive industries under Taiwan’s climate change policy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2012, 16, 2631–2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Energy-Related Emissions of CO2 Statistic and Analysis. 2020. Available online: https://www.moeaboe.gov.tw/ECW/populace/news/wHandNews_File.ashx?file_id=18440 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Chou, K.T.; Liou, H.M. Climate change governance in Taiwan: The transitional gridlock by a high-carbon regime. In Climate Change Governance in Asia; Routledge: London, UK, 2020; pp. 27–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Agency. Electricity Information. 2019. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/8237c23b-1fde-41a8-ba8b-9d136f0eafef/Electricity_documentation.pdf (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- NUS Consulting Group. 2005–2006 International Water Report & Cost Survey. 2006. Available online: https://www.vewin.nl/SiteCollectionDocuments/Nieuws%202007/2006WaterSurvey-NUS.pdf (accessed on 2 February 2021).

- International Water Association. Total Charge Drinking Water for 160 Cities in 2015 for a Consumption of 200 M3. 2015. Available online: http://waterstatistics.iwa-network.org/graph/9 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- The Conference Board. Manufacturing Hourly Compensation Costs. 2006. Available online: https://conference-board.org/ilcprogram (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Martinez-Covarrubias, J.; Garza-Reyes, J.A. Establishing framework: Sustainable transition towards a low-carbon economy. In The Low Carbon Economy; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 2017; pp. 15–31. [Google Scholar]

- Low-Carbon Heat Solutions for Heavy Industry: Sources, Options, and Costs Today. 2019. Available online: https://www.earth.columbia.edu/projects/view/1995 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- China National Federation of Industries. The CNFI White Paper 2008—Issue on Industry; CNFI: Taipei, Taiwan, 2008; Available online: http://www.cnfi.org.tw/front/bin/ptdetail.phtml?Part=2008-2&Category=100003 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- China National Federation of Industries. The CNFI White Paper 2015—Issue on Industry; CNFI: Taipei, Taiwan, 2015; Available online: http://www.cnfi.org.tw/front/bin/ptdetail.phtml?Part=2015-2&Category=100003 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- China National Federation of Industries. The CNFI White Paper 2016—Issue on Industry; CNFI: Taipei, Taiwan, 2016; Available online: http://www.cnfi.org.tw/front/bin/ptdetail.phtml?Part=2016-2&Category=100003 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Sun, M.T. Taiwan Economic Review and Outlook in 2015–2016. TIER Mon. 2016, 39, 65–72. [Google Scholar]

- Carbon Disclosure Project. 2021. Available online: https://www.cdp.net/en/scores (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- China National Federation of Industries. The CNFI White Paper 2012—Issue on Industry; CNFI: Taipei, Taiwan, 2012; Available online: http://www.cnfi.org.tw/front/bin/ptdetail.phtml?Part=2012-2&Category=100003 (accessed on 17 October 2022).

- Tung, G.H. Professional Lies: Nuclear Electricity Industry Discourse Transition and Environmental Crisis. 2014. Available online: https://rsprc.ntu.edu.tw/zh-tw/m01-3/en-trans/84-professional-lie.html (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Tseng, C.-W. Research on Energy Taxation. Ministry of Finance’s Taxation Reform Commission. 1989. Available online: http://nccur.lib.nccu.edu.tw/handle/140.119/71962 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Shaw, D.-K.; Hunang, Y.-H. Project Report: Research on Green Taxation. Investigated. 2008. Available online: https://www.grb.gov.tw/search/planDetail?id=1647469 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Shyu, C.W. Taiwan’s Governance and Policy on Responding to Climate Change. HSSNQ 2014, 15, 25–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, I.-J. Conclusion on National Energy Conference: Progress and Review Report. 2009. Available online: https://e-info.org.tw/node/42533 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Bureau of Energy. The Era of Paying for the Environment: A Brief Introduction of Carbon Tax. 2003. Available online: https://magazine.twenergy.org.tw/Cont.aspx?CatID=31&ContID=362 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- National Council for Sustainable Development. R.O.C. Strategic Guidelines on Sustainable Development. 2000. Available online: https://nsdn.epa.gov.tw/taiwan-sdgs/taiwan-agenda-21 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Bureau of Energy. An Environmental Sound Taxation on Carbon. 2005. Available online: https://magazine.twenergy.org.tw/Cont.aspx?CatID=28&ContID=872 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- Bureau of Energy. Views of the Ministry of Economic Affairs on the Promotion of Energy Tax. Energy Magazine. 2006. Available online: https://magazine.twenergy.org.tw/Cont.aspx?CatID=28&ContID=1051 (accessed on 12 December 2020).

- China Technical Consultants Inc foundation. Workshop Minutes: The Introduction of the Energy Tax. 2007. Available online: https://www.ctci.org.tw/8838/research/26382/26448/ (accessed on 2 December 2020).