1. Introduction

In Poland, the electricity market, as in other European Union Member States, operates on two levels. The first is the wholesale market, with the participation of electricity producers and wholesale buyers. The legislator does not exclude the participation of final customers at this level. However, the cost of participation, the problem of balancing supplies, the necessity to have telecommunications and computer systems as well as personnel costs effectively limit this participation, usually to large electricity consumers. The second level is the retail market, where energy producers offer individual customers energy supplies, competing on price, delivery terms, and additional services [

1]. Both these markets must be shaped in accordance with the priorities of the state’s energy policy, which include: (1) security of energy supplies, i.e., ensuring conditions enabling the coverage of the current and future demand of the economy and society for energy of an appropriate type and required quality; (2) socially justified energy prices, i.e., establishing an energy price policy, in which the price would result from competitive market mechanisms or from regulations of an independent, apolitical state authority excluded from ministerial structures in order to balance the interests of energy consumers and suppliers; (3) compliance with the requirements of environmental protection in the conditions of market economy. The aim of the energy policy of the state is security in the field of energy, which would, at the same time, ensure the competitiveness of the economy, energy efficiency, and reduction in the impact of the energy sector on the environment, which is caused by the optimalization of the use of state’s energy resources. Energy security relates to the current and future fulfillment of customers’ needs for energy in an economically and technically justified way, while maintaining the requirements for the protection of environment. This relates, in particular, to a guarantee of an interrupted supply of raw materials, production, transmission, and distribution, i.e., all the elements of energy chain. The cost of energy is an element of every action and every produced product being the effect of economic relations; therefore, energy prices have a significant impact onto the competitiveness of economy entities and their products. It is also worth noting that the negative influence of the energy sector on the environment creates an energy imbalance, which must also be taken into account [

2] (p. 10). Such creation of the vision of the electricity sector is conditioned, inter alia, by the current state of the retail market, its structure, and forecasts of electricity consumption, as well as the legal and actual status of individual market participants.

In the Polish legal system, the retail energy market is largely driven by the Energy Law Act [

3], which, in terms of these considerations, from the point of view of the state’s tasks [

4], primarily includes: (1) retail price regulation including measures to limit prices or the behavior of entrepreneurs at the retail market level; (2) public service regulation covering measures to guarantee to all categories of consumers, regardless of their social status, income, or geographical location, and access to products and services that have a basic meaning for the fulfilment of their social needs, as with elementary service obligations (public service obligations); (3) regulation of dispute resolution, which concerns quasi-judicial methods of dispute resolution; and (4) protection of competition, which comes down to controlling the anticompetitive behavior of entrepreneurs and mergers [

5] (p. 4). It should also be clarified that, when speaking about the legal framework of the retail electricity market, it should refer to transformed energy, thus excluding all forms of primary energy from the scope of this regulation. This means that, when using such primary energy sources as solar radiation energy, aerothermal energy, hydrothermal energy, geothermal energy, hydropower, sea current, wave and tidal energy, and wind energy, only energy processed in the process of using the above-mentioned energy sources is covered by the regulations in question. Similarly, nuclear energy is not covered by the definition of energy within the meaning of Art. 3(1) of the Energy Law Act. These provisions directly distinguish electricity as one of the types of energy transformed in energy processes. What is more, the modern electricity market, also in the retail aspect, is undergoing far-reaching changes, which increasingly activate consumers (creating, among others, the category of prosumers). With the development of cheap digital technologies and the rise of informatization, consumers became active participants in markets and started to offer their personal products and services. Such consumers are important foundations of goals of the European Union, which include achieving wise, balanced, and comprehensive growth in Europe. In the sector of energy, active consumers play a very important role in the promotion of competition, which ensures reasonable energy prices and safety of supply, as well as contributions to the environmental and climate goals of the European Union. By investing in more efficient uses of energy, consumers have become important drivers for the energy transition. However, it is very important to remember that the legal frameworks created by the state do not fully make this active role easier [

6] (p. 227). For this reason, it becomes so important to discuss modern tools for the protection of consumer rights, which must survive and adapt to new market realities.

Within the framework of these considerations, it is necessary to focus on the group of entities of the retail energy market, which are final customers, and more precisely, a subcategory of final customers, household customers as entities that are granted consumer protection within the meaning of the European Union law.

2. Literature Review

The literature indicates many specific features of the retail electricity market, which directly affect the actual and legal situation of consumers. For example, the representatives of the Danish doctrine noted that the retail energy market is characterized by a high level of concentration, despite numerous small participants. However, a distinguished feature of this market is also the presence of horizontal mergers. Recently, a strong increase in number of products together with a slight decrease in the gross retail margin has been observed. However, on this market, large differences in prices between the retailers occur, which cannot be omitted. Despite the existing possibilities, a big number of consumers has never switched. These unaware consumers are the main users of price products, which are the retailer’s default products. As a consequence, those consumers purchase the products for a significantly higher price when compared with similar products chosen by aware consumers [

7].

The literature indicates that the basic assumption of market implementation is the separation of electricity as a product from its supply as network services (transmission and distribution, quality assurance, and supply coordination and demand balancing). As is noted, for example, in the literature, programs that allow customers to make a choice separate the phase of energy distribution, which continues to be a regulated monopoly, from the arrangements considering services related to electric generation in wholesale markets, which are characterized by high competitiveness. Those arrangements also consider the resale of services of this kind to final retail consumers [

8] (p. 1). This approach enables the separate pricing of products and services and the introduction of competitive rules for electricity trading for the needs of final household customers.

Electricity market analysts emphasize in their studies that the separation of a product from a service is a basic feature of the electricity market, which must also ensure: (1) equal treatment of all participants, (2) free access to the market limited only by technical or financial conditions, (3) free formation of the electricity price as a result of balancing demand and production, and (4) regulated pricing for network activities (tariffing) due to the existence of network monopolies, as well as priority treatment of electricity supply in relation to financial transactions concluded on this market [

1]. There is both a competitive and regulated area in the retail electricity market. From the perspective of these considerations, the regulated area is of particular importance.

As indicated in the doctrine, in the regulated area of the retail electricity market, final customers appear as the main entities to whom distribution companies ensure the supply of this energy, and its sales are based on the tariffs approved by the President of Energy Regulatory Office (the ERO) (regulatory entity). Undoubtedly, this area is designed to ensure adequate access to electricity resources, which is, after all, an indispensable element of standard civilization equipment [

9]. In the competitive area of the retail market, final customers, depending on the volume of annual electricity purchases, are successively granted (according to the schedule specified by the minister responsible for economy) the right to choose their supplier (third party access). In such a case, final customers may buy energy from suppliers, which are distribution companies or intermediaries in energy trade (trading companies, stock exchange), or directly from the producers. However, when it comes to the transmission service, the final customers settle accounts with the energy company to which they are connected under the applicable tariffs for these services. A clear separation of the regulated area is also largely conditioned by the fact that consumers themselves are not a homogeneous category. As indicated in the doctrine, there are two categories of consumers in the retail energy market: savvy and non-savvy consumers. M. Armstrong notes that there are two elemental concepts of savviness to consider. According to the first category, a consumer should have proper information about the prices and quality of the product, which allows for the evaluation of the product’s idiosyncratic value. For example, a savvy consumer can assess the value and features of the product by looking at its label. Alternatively, consumers might be systemically savvy if they understand the principles of a particular market. For example, savvy consumers know that good quality of products is connected with higher price, and therefore they have to make a choice of the product or service, which would result in a balance between the price and quality adequate to their financial possibilities. Savvy consumers know and are able to plan their future needs and behaviors, while non-savvy consumers do not have such skills and are not able to establish their future needs in a correct way [

10] (p. 2).

Therefore, as it is emphasized in the literature relating to the European Economic Area, the competition showing up on energy retail markets raises a lot of discussion. In theoretical considerations, problems of imperfections of those markets arise, such as the costs of switching to consumers, the necessity to select services of complex nature, and problematic requirements of information, which create weak points to the functioning of these markets, at least to the final household customers. On the other hand, practice shows that an opening of the market does not always result in lower prices, and quite contrary, might lead to the establishment of higher prices for some categories of consumers [

11] (p. 25). There is no doubt, however, that the opening of energy retail markets, which can be currently observed, has a significant impact on the final household customers. The functioning of energy suppliers in a more competitive market forces them to specific behaviors. These include setting up lower prices, offering higher quality services, and broadening their catalogs of services. The suppliers, regardless of their size, have to compete for the consumers on the energy retail market. This does not mean that those liberalized markets do not have weaknesses. The consequences of offering lower prices to final household customers are binding those consumers with long-term contracts, the stipulations of which depend largely on the changing conditions of trade and wholesale markets. Practice has also shown that the bankruptcy of the suppliers is particularly painful for the final household customer [

12] (p. 317). However, the experience of researchers, not only in EU domestic retail markets, shows that, even in highly developed and transparent markets, consumers often accept sub-optimal solutions and switch to contracts that are not the cheapest. Across two independent electricity market datasets, it was found on aggregate that consumers making a choice solely on the criterion of price gain less than a half of possible benefits. This conclusion can be justified by high search costs, but the result, according to which at least 17% of consumers did not gain any benefits from the switch, cannot [

13] (pp. 647–651). This requires the development of modern instruments of guarantee for consumer rights.

3. Materials and Methods

In order to fully analyze the above issue, the authors will use research methods characteristic of social sciences. In order to characterize the Polish retail electricity market, basic statistical tools were used. In particular, these are descriptive statistics for the basic variables describing the analyzed market and linear regression methods that allow for the assessment of trends that can be observed on the Polish retail electricity market. The tools used allow for an objective characterization of this market. This study is a theoretical study; therefore, statistical analyses are only illustrative and are devoid of elements of empirical research.

For this reason, legal analyses based on dogmatic-legal and analytical methods with elements of comparative law analysis are of crucial importance for this study. The latter is important because it is crucial to see the researcher’s field of activity in a spatial, horizontal, and geographical sense. When it comes to the subject of dogmatic-legal analysis, it is both the content of the law, but also its interpretations resulting from case law and literature. The most important goals of the research method used in legal dogma include the search for answers to the question about the validity of norms (what norms are in force in the system), their interpretation, reflection on the practice of applying norms, their systematization, shaping concepts, and formulating de lege ferenda conclusions. F. Longchamps put it this way: “it is intellectual activity which, through the interpretation of statutory texts, conceptualization, ordering, removing contradictions and filling the so-called gaps in the law, seeks an answer to the quid iuris question. How is it according to the law, what does the law state, what is the content of the legal order in its general principles and detailed solutions” [

14] (p. 8). This is also how the purpose of this study should be understood—to determine the content of the civil law structure of protection of consumer rights on the retail electricity market, the values that this structure implements, the concepts it uses for this purpose, and above all, the instruments that appear or could appear in it in the future. Dogmatic analysis will be conducted on the provisions of the Polish Energy Law Act and the Code of Civil Procedure, and to the necessary extent also on the provisions of European Union law co-shaping the legal status of household customers on the retail electricity market of the Member States. As to the analytical method, which is said to be “created by lawyers for lawyers”, it will be used for an in-depth analysis of individual, fragmented aspects of the achievements of the Polish judicature relating to regulatory proceedings and the detailed views of Polish and foreign doctrine regarding consumer protection instruments on this market, taking into account the original structure of combining administrative proceedings and relevant decisions with civil procedural law having highly specific features, including a system of means of appeal and regulations based on the principle of equality of the parties.

It is this original combination of the two branches of procedural law that makes the Polish system of measures of legal protection for household customers on the retail electricity market interesting, and therefore worth an in-depth analysis. This is also due to the fact that judicial practice shows that courts have a significant role in enforcing consumers’ procedural rights [

15] (p. 205). This makes the Polish experience an example for those countries which are currently transforming their electricity markets.

4. Polish Retail Electricity Market Characteristics (Prepared on the Basis of the ERO Reports and Data from the Polish Central Statistical Office)

When describing the Polish electricity market, it is necessary to start with the systematic decline in the volume of domestic electricity production. In 2020, this volume reached the level of 152,308 GWh, which means a decrease of 4.1% compared to 2019 (in 2019 there was a decrease by 3.9% compared to 2018). This means that the production volume drops for the third year in a row, which is a very disturbing tendency. In turn, electricity consumption in 2020 amounted to 165,352 GWh and is lower than in 2019 by 2.3%.

The decrease in domestic consumption of energy in Poland was slightly smaller than the decline in GDP in 2020, and amounted to −2.8%, which was in accordance with the prognosis of the Polish Central Statistical Office.

Figure 1 shows the percentage changes (year on year) of: gross domestic product (GDP), electricity production, and electricity consumption.

The tendencies that can be observed on the Polish energy market are unfortunately not favorable, and it is not only an effect of the pandemic. The negative trends and relationships between energy production and consumption in recent years are clearly visible. It should also be noted that, in 2020, in the state balance of flows of physical energy, the import took 11.8% of the whole revenue, and the export took 4.2% of the energy consumption. Compared to 2019, the share of imports increased by 1.7%, and the share of exports increased by 0.1%.

The discussed relations are significantly influenced by the structure of electricity production in Poland, which has undergone minor changes in recent years.

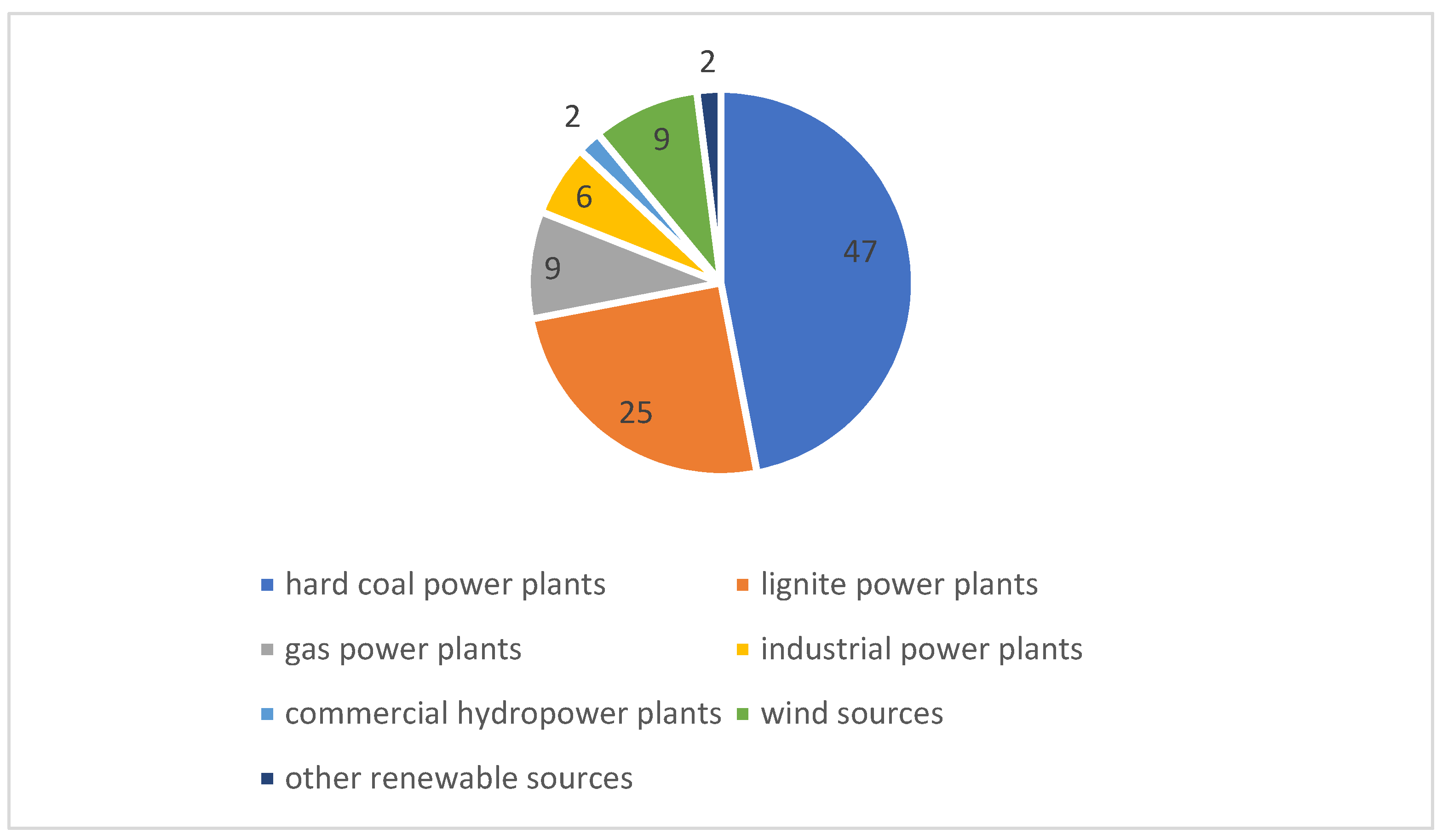

Figure 2 shows the structure of electricity production in Poland in 2020.

The energy production structure in 2020 did not change in a significant way compared to 2019. The vast majority of energy production in Poland is still based on conventional fuels, i.e., lignite, and hard coal, although their share has slightly decreased from 75% to 72%.

The Polish electrical power sector is facing major changes, which are a consequence of the energy transformation process that has already begun. On the one hand, it is a huge investment effort that must be carried out in a socially responsible manner and for which appropriate regulatory conditions must be created. On the other hand, the energy transformation also requires the implementation of a new market model. Infrastructure companies should support the development of new types of market participants, such as communities or energy clusters, because only well-managed civic energy will be able to support the national electrical power system. Therefore, it is necessary to create such a market model that will enable the functioning of new entities while ensuring the stable operation of the distribution and transmission networks.

The retail energy market in Poland is significantly influenced by the structure of the entities on the wholesale energy market. For several years, the PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna S.A. (Warsaw, Poland) capital group has the largest market share in the electricity production sub-sector. In 2020 and in 2019, its share was 40.6%. In the analyzed years, this entity was also a leader of the retail energy market of sales to final household customers. The narrow group of dominating entities, taking into consideration the amount of energy which they transferred into the network (this concerns the amount of energy delivered to final household customers), in 2020 continued the descending trend from 2019 and was 63.8% (which is a decrease by 2.6% in comparison to 2019). An observable descending trend was also recorded for the share of this narrow group of dominating entities—a decrease by 3.7%. The three largest producers are grouped in capital groups: PGE Polska Grupa Energetyczna S.A., ENEA S.A. (Poznań, Polonia), and TAURON Polska Energia S.A. (Katowice, Polonia). These producers have a total of almost 2/3 of the installed capacity and are responsible for over 60% of energy production in Poland. It is worth noting that, among the main entities in the energy production market, in 2020, the importance of producers operating in the ENEA S.A. capital group decreased. This is the effect of a decrease in electricity production by producers operating in this group by nearly 14%.

The retail market, which is the subject of the article, is the market to which the final customer purchasing fuel and energy for their own use is a party to the transaction. The participants of the retail market, apart from final customers (households, enterprises), are enterprises managing the distribution network, the so-called distributors, including distribution system operators (DSOs) and electricity sellers (trading companies). In 2020, based on data from the ERO, out of 17,934,464 customers in the retail market, 15,762,416 (88%) were households. Customers in this group used over 32 thousand MWh of electricity, which accounts for over 23% of the total volume of electricity sold in Poland.

The supply side of the retail energy market consists of energy sellers offering this commodity to final customers, including six sellers operating within the structures of capital groups. These sellers offer electricity to households under the public law obligation (ex officio sale, with a price that is, in principle, regulated) and conduct markets sales (with a price set without any restrictions) to final household customers and other groups of customers. The second group consists of sellers in entities that also take care of distribution of energy (there were 183 of them in 2020), and another group consists of independent entities selling energy—such entities are not present on the Polish market. The data of the ERO shows that as of 31 December 2020, 63% of households being customers of these sellers were buying energy based on contracts with a tariff controlled by the state, while the remaining 37% were buying energy at prices that were offered by professional participants in the market.

The year 2020, in which many areas of life have changed radically due to the COVID-19 epidemic, also brought amendments resulting in changes in regulations—a lack of possibility to suspend supplies of energy by the suppliers. The epidemic state meant that an energy company engaged in business activities in the field of transmission or distribution of electricity may not, inter alia, suspend the supplies in the absence of the customer’s acceptance to the installation based on prepayment. The supplier cannot also suspend the supply of energy (even if the seller asks for it), even in the situation of lack of payments from the customer. Later regulations limited the group of consumers who can gain from the special treatment to final household customers, who can be described as vulnerable, and to a limited group of entrepreneurs who, due to the inability to conduct business activity, lost their income and would not be able to pay the dues. The implementation of the epidemic regulation has been clearly limited in time to 6 months from the date of announcing the state of epidemic threat or state of epidemic. These regulations are of significant importance for energy producers, increasing the risk of the implementation of financial plans.

In 2020, after the period of freezing of electricity prices in 2019, the prices were significantly increased, especially in the group of consumers using the low voltage grid. The level of prices in 2020, together with a visible increase in prices of coal and high costs of CO2 emission allowances, also resulted in a reduction in the level of energy used in the system, due to the outbreak of the COVID-19 epidemic by increasing fixed costs per unit of energy.

Table 1 includes data on energy prices and fees for distribution in the fourth quarter of the discussed years for consumers with comprehensive contracts. The maximum year-on-year increase in the price of energy oscillates around 23% in the C tariff group, and it is lower (over 22%) in the household group. It is worth noting that the cost of energy supply did not increase drastically, because the high increase in prices of energy was limited by a small increase in distribution fees (in the group of households—3.29%, and in the C tariff group—7.45%). It is also important that the increase in fees of distribution in 2020 was preceded by a drop in 2019, and in some categories of tariff groups (A and G), it was still lower than in 2018. From the customer’s perspective, the most important aspect is the level of the average price for which they buy energy at the point of consumption (i.e., together with the distribution service). This value increased on average by 13.35%; the lowest increase (by 4%) was observed in the biggest category of consumers of energy, and the highest (by slightly over 16%) in the C tariff group.

It should be added that

Table 1 is only illustrative and aims to show the price formation as one of the characteristic element of the Polish energy retail market. Due to the theoretical nature of the article, empirical research in this respect has not been moving towards an analysis that is characteristic, in particular, for legal sciences, and concerning the interpretation of the applicable legal status against the background of information on the structure of this market. According to I. Zachariasz, an analytical approach to the theory of law without the observation of social relations “leads to building a theory of law that is completely contrary to the generally accepted methodological principles, or rather to a set of loose views on the law or a description of the contexts in which we get to know this law, which means in fact “pure” linguistic analysis” [

16] (p. 18).

It should be emphasized that the price does not constitute an exclusive criterion, showing the situation of consumers on the retail electricity market, as consumer rights also apply to such issues as the quality and continuity of electricity supply or knowledge of its source of origin. Certainly, in the latter scope, the so-called greenwashing has certainly become an important phenomenon for consumers’ awareness. In the context of energy tariffs, greenwashing is the act of purchasing certificates by a supplier without buying the power they relate to. In practice, this misleads consumers as to the true origin of the electricity. Consequently, it is necessary to be aware of the complexity of the phenomena occurring between the participants of the retail electricity market and their legal consequences, as well as in the area of possible compensation claims. However, it is beyond the limited scope of this study to analyze all aspects of the interaction between consumers and professional market participants.

5. Legal Status of a Household Customer in the Energy Law

Internal energy retail markets, as a principle, did not meet the expectation of the consumer, and these markets are constantly assessed as offering the worst consumer conditions. This situation has not been changed by the introduction of broad legislative changes in the EU law. Energy consumers often have difficulties in actual use of their privileges. Still, the fundamental feature of these markets is the lack of a well-functioning systems of consumer rights [

17] (p. 3).

One of the basic protective instruments is the creation of a proper definition of individual legal categories of consumers on the retail electricity market. Each Member State of the EU should define the concept of vulnerable customers, which concerns energy poverty and, inter alia, the guarantee of supply of electricity to such customers in justified situations. Member States must ensure that the extraordinary legal situation of vulnerable customers is taken under consideration [

18] (p. 7).

The provisions of the Polish Energy Law Act are of fundamental importance for determining the legal status of household electricity customers on the Polish retail electricity market as one of the basic categories of final customers. Pursuant to Art. 3(13a) of the Energy Law Act, the final customer is a customer who purchases energy for their own use. Own use does not include electricity purchased for storage or consumed for production, transmission, or distribution, and electricity purchased for the purpose of transmission and distribution [

19]. This group of consumers includes the category of household electricity customers, i.e., final customers purchasing electricity solely for its consumption in the household (Art. 3(13b) of the Energy Law Act). In the case of multi-apartment houses, each of the owners or users of individual apartments has contracts concluded with energy companies regarding the sale of electricity and gas; therefore, they are the consumers of fuels or energy. However, the group is not uniform, because the Polish legislator—as part of the social policy instruments—has also created a subgroup of vulnerable electricity consumers, i.e., people who have been granted a housing allowance within the meaning of Art. 2 paragraph 1 of the Act on housing allowance [

20], who are parties to comprehensive contracts or electricity sales contracts concluded with an energy company and reside in the place where electricity is supplied. The housing allowance is a benefit dedicated to people whose financial situation has deteriorated or who, due to their low income, are not able to pay for an apartment. The idea of housing allowances in the Polish legal system comes down to the creation of public aid instruments for the maintenance of tenant- or privately owned apartments in a situation where the beneficiary is not able to cover their maintenance expenses on their own. A vulnerable electricity consumer can receive the so-called energy allowance, constituting a kind of subsidy on electricity bills. The calculation and allocation of these allowances are not the competences of energy companies, but the tasks of communes. It is worth adding that the Polish approach to this category of final customers is narrowed in relation to the subjective scope sometimes adopted in foreign doctrine. It is indicated that vulnerable consumers are consumers who are disadvantaged due to some special circumstances. This group of consumers may have a lower income available to meet the prices of energy or may be in a situation where the need occurs to buy a larger amount of energy (for instance, they have old and inefficient household appliances). This does not exclude a situation in which consumers which will be vulnerable due to other circumstances (such as disability, inability to access the internet) occur on the market [

21] (p. 7). This issue is so important that it has also been noticed in countries that want to become EU members in the future, and for this reason, they imitate many EU legal solutions. A good example is the Serbian system, where consumers were granted the right to support if they are in a social need (for example, due to low pensions, disabilities, need for medical care, poverty, or large families). The identification of those categories of vulnerable consumers is a duty of social care centers that create lists for distribution companies [

22] (p. 173).

Thus, the scope of the definition of household customers is narrow and unambiguous—it refers only to energy consumption for household needs and thus not for the purposes of activities performed in business premises that are also used for household needs [

4]. The concept of a household should be understood as “individuals or groups of people living together and maintaining themselves together, most often linked with each other by family ties” [

23] (p. 411). Single people and people living with other people but maintaining themselves separately form separate, one-person households. From the perspective of defining vulnerable consumers, the concept of a household as defined in the housing allowance Act (Art. 4 of this Act) is of fundamental importance. It is a household run by a person applying for a housing allowance, independently occupying the premises or a household run by that person jointly with their spouse and other persons permanently living and managing with them, who derive their right to live in the premises from that person’s right.

The indicated legal definitions introduced by the Polish legislator exemplify the provisions of European Union law. Pursuant to Art. 2(3) of Directive 2019/944, “final customer” means a customer who purchases electricity for own use, and pursuant to Art. 2(4) of the Directive, “household customer” means a customer who purchases electricity for the customer’s own household consumption, excluding commercial or professional activities [

24]. As indicated in the doctrine, the separation of this group of consumers (also belonging to the group of final customers) is due to the granting of certain privileges, and this is primarily the right to terminate the contract for the supply of electricity in a simplified manner (Art. 4j paragraph 4 of the Energy Law Act) and the rights related to the ex officio appointment of a seller (Art. 5a of the Energy Law Act) [

25] or issues related to the complaint procedure.

Due to this special status of final household customers, attention should be paid to the consumer rights they have been granted in the retail electricity market.

6. Catalog of Consumer Rights on the Retail Electricity Market

The catalog of consumer rights on the retail electricity market in the Member States of the European Union is shaped in the same way not only due to the requirements of the EU legal system, which requires a uniform approach to consumer rights in individual internal legal systems, but also due to common characteristics of the retail electricity markets in those countries that are noticeable, inter alia, by organizations whose task is to defend consumer rights. These features determine not only the current state of protected rights, but also set directions for changes in the future. It is mainly indicated that: (1) access to energy is not assured in many Member States of the EU; they should ensure that operative procedures minimizing the risks of deprivation of this access are present; (2) consumers should have access to proper information on the offers that they can use and have the possibility to analyze such offers with the use of objective tools; (3) the conditions considering contracts between consumers and providers should be clear and understandable; (4) consumers should also have the right to protection against misleading and unfair marketing practices; (5) the contractual conditions and related instruments of consumer protection established by the Third Energy Package should support consumers to gain information about the rights in this market; (6) consumers should have a possibility to evaluate and, in appropriate situations, change their consumption behaviors—this will be assured by appropriate information inter alia on the bills; (7) changing suppliers should be as easy as possible for final household customers—proper regulations at national and EU level should be adequate to the needs of the consumers in this area; and (8) the introduction of effective ways of resolving disputed between consumers and service providers will translate into building proper relations in this sector and effective enforcement of consumer rights [

17] (p. 3). The introduction of these solutions is forced in individual Member States primarily through the application of directives that set a goal that all EU countries must achieve. The way in which it is achieved is determined by individual countries through their own legal acts. However, failure to achieve the set goal within the time limit set by the directive results in its direct application in the internal legal system. An example of such a directive is Directive 2009/72/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 13 July 2009 concerning common rules for the internal market in electricity and repealing Directive 2003/54/EC [

26].

The electricity consumer has, above all, the right to: (1) access to the network, expressed in the possibility of connecting to the distributor’s network, if there are technical and economic circumstances essential for connecting to the electricity network and supplying energy, and the consumer applying for the conclusion of the contract fulfills the conditions for connection and receipt and meets the legal conditions concerning the connected real estate, facility, or premises (e.g., rental agreement, ownership right); (2) receive electricity supplied by the distributor’s network from a selected seller, in a continuous and reliable manner; and (3) non-discriminatory treatment, i.e., equal treatment of all consumers who are in a similar situation by the distributor. In this case, it is worth paying particular attention to the need to properly define access to electricity, which is sometimes perceived in a broader context of human rights. In the former EU Member State Great Britain, it is defined quite vaguely, emphasizing that “equity of access to basic energy services for cooking, space heating, and lighting, like access to water, could be considered a human right” [

27] (p. 30). Similarly, the French legislator indicates that the domestic legal structure “contributes to social cohesion by satisfying everyone’s right to electricity” [

28] (p. 13).

On the other hand, under the right to purchase electricity, the final household customer may do so from a selected seller or from an ex officio seller in the event of not exercising the consumer’s right to choose a seller. This construction is introduced in the internal legal systems of other EU Member States. In Spain, customers have the right to choose their supplier and may contract their supply with either an authorized supplier or an authorized agent in the generation market (direct consumers only) [

29]. Moreover, the consumer has the right to use the electricity distribution service, billed on the basis of the rates and conditions of their use, resulting from the distributor’s tariffs approved by the regulatory authority, which is the President of the ERO. It is worth noting that these constructions, introduced in individual EU Member States, already tend to depart, at least partially, from excessively rigid price regulations. For example, in Spain, just like in Poland, the new Electricity Act was enacted by the Law 24/2013 of 26 December, introducing the economic and financial sustainability. The Electricity Act distinguishes the consideration for the use of networks and the rest of payments from the rest of the system costs. Besides this, the Electricity Act regulates the supply of “voluntary prices for the small consumer”. The concept of rigid pricing will be limited to the most vulnerable consumers in order to maintain the social bond [

30].

As part of deregulation processes, the consumers choose the type of contract because they decide whether they want to conclude two contracts—one with the seller and the other with the distributor, or one contract, i.e., a comprehensive contract, on the basis of which electricity will be sold and delivered. Moreover, legal changes go hand in hand with changes in the way this market operates, especially in the area of price formation and the provisions of electricity supply contracts, which can be seen especially on the Spanish market. An analysis of this market shows that companies in the electricity retail market have been forced to adapt and modify their service offer and delivery as a result of the deregulation of the market: on the one hand, by incorporating new ways to generate and consume energy, e.g., self-generation or self-consumption; on the other hand, by automating and integrating communication services and channels to interact with customers, as well as providing additional functionalities and services related to the monitoring, billing, and managing of energy consumption. In particular, in relation to the digitalization of commercialization activities and improvement of customer experience, companies feel the need to provide digital means to manage service contracting, payments, and online billing [

30]. Similar phenomena are also noticeable in the related Portuguese market, which repeats the same legal regulations over time [

31], or in the Italian market, where residential customers and small businesses who do not choose their supplier are served under a regulated tariff named “maggior tutela” (greater protection) and supplied by the local distributor at a price set by the regulatory entity [

32].

Information rights are a separate category of consumer rights of final household customers. The consumer has the right to obtain from the energy company information on planned changes to the concluded contract, along with information on the right to terminate the contract in the event of non-acceptance of the new conditions, with the exception of changes in prices or rates specified in the tariffs approved by the President of the ERO (obligation of the seller and distributor), as well as in the case of an increase in prices or rates of charges for the supplied electricity specified in the approved tariffs, within one billing period from the date of the increase (obligation of the seller under the sales contract or comprehensive contract). Information about the increase should be provided in a transparent and understandable manner for the consumer. The consumer must also have knowledge about the possibility of changing the seller and the procedure to be used when changing the seller (obligation of the distributor), electricity billing rules, current tariffs (obligation of the seller and distributor), and the method of submitting complaints and settling disputes (obligation of the seller under the sales contract or comprehensive contract). The final household customer also has the right to know the structure of fuels or other energy carriers used to generate electricity sold in the previous calendar year. The supplier has also an obligation to notify where information on the environmental impact of generating this energy is available (obligation of the seller). Similar constructions also appear in other EU Member States, e.g., in Germany, in particular, network operators must publish on their website what information needs to be provided by the applicants, information on the terms and conditions of the standard network access contract, and frequently updated information on the grid situation, including existing or potential capacity bottlenecks [

33].

In order to properly plan electricity expenditure, the consumer also obtains information on the amount of electricity consumed in the previous year and the place where information is available on the average electricity consumption for a given connection group, energy efficiency improvement measures and energy-efficient technical devices (obligation of the seller), and information on the amount of electricity consumed in the billing period to which the calculation relates (obligation of the distributor or seller in the case of a comprehensive service, in the settlement attached to the invoice). The consumer also has the right to obtain knowledge of how the measurement and billing system was read—in particular, the way in which the reading was performed by an authorized representative of an energy company or a reading made and reported by the consumer (obligation of the distributor or seller in the case of a comprehensive service, in the settlement attached to invoices), as well as the method of determining the amount of energy consumption in a situation where the billing period is longer than a month, especially when the first or last day of the billing period does not coincide with the dates of readings or when there was a change of prices or fee rates during the billing period, or where this information is available (obligation of the distributor or seller in the case of a comprehensive service, in the settlement attached to invoices).

The rights of final household customers, in particular, those informed, are of fundamental importance to provide them with an appropriate level of legal protection as weaker entities on the complex, multi-entity retail electricity market. One of the instruments of this legal protection are decisions of regulatory authorities—the President of the ERO in the Polish legal system.

7. Protective Function of the Decisions of the Regulatory Authority

In the Polish legal system, the President of the ERO is the central body of government administration that performs tasks in the field of fuel and energy regulation and promoting competition. Pursuant to Art. 23 paragraph 1 of the Energy Law Act, the President of the ERO regulates the activities of energy companies in accordance with the law and the state energy policy, aiming to balance the interests of energy companies and fuel and energy consumers. In the discussed scope, the appropriate application of protection mechanisms in the retail electricity market is of particular importance. As indicated in the literature, protective instruments can be designed in relation to the whole market. The catalog of policies is wide, but the most popular are price cap and default tariff. Default tariffs exist in both open and regulated retail energy markets. In a liberalized market, the role of a default tariff is to guarantee that access to energy continues under special conditions for various categories of consumers, for example, those who have never signed a different contract since the market was opened, or those whose retail contract has expired but who have not signed another contract. Similarly, price cap is a policy that can be applied to ensure protection of a subset of the market or the whole energy market [

34] (p. 17).

The regulatory authorities on the electricity market are present in all EU Member States, and their competences depend on the degree of deregulation of the retail market made in accordance with EU law standards, for example:

- (1)

The Energy Regulatory Authority in Denmark (Forsyningstilsynet)—an independent body acting as a competition authority in the Danish energy sector; it is subordinate to the Ministry of Energy, Supply and Climate; the goal of the Danish regulatory authority is to protect the interests of consumers in the procurement sectors by working towards high efficiency, the lowest possible consumer prices in the short and long term, safe and stable supply, profitable technology development, and a profitable ecological transition;

- (2)

Commission de Régulation de l’Energie in France—independent administrative body in charge of regulating the French electricity and gas markets; its role is to ensure that these markets in France function without any disruptions, for the benefit of end consumers and in line with energy policy objectives. The basic tasks of this body are: (a) guaranteeing independence for system operators, (b) establishing harmonized rules for the energy networks and markets to ensure that energy is able to be transferred without any obstacles between EU Member States, (c) ensuring competition between energy suppliers for the benefit of consumers, and (d) ensuring that consumers have access to fair service at a reasonable price;

- (3)

Federal Network Agency for Electricity, Gas, Telecommunications, Posts and Railway in Germany (Bundesnetzagentur-BNetzA)—the federal agency of the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. In the electricity market, the Agency is responsible for guaranteeing non-discriminatory consumer access to networks and regulating the fees. The Agency is not responsible for independent energy companies; these tasks remain with authorities determined by state law. The Bundesnetzagentur has the roles set under the Renewable Energy Sources Act (EEG), in particular: (a) determining the level of payment for installations for the generation of energy from renewable sources; (b) monitoring the nationwide EEG equalization scheme process between the electricity suppliers, and the distribution network and transmission system operators; (c) publishing the monthly information on the newly installed renewable energy installations; and (d) conducting the auction process for renewable energy installations;

- (4)

The Regulatory Authority for Energy, Networks and the Environment in Italy (Autorità di Regolazione per Energia Reti e Ambiente)—an independent administrative body of the Italian Republic, whose task is to promote the development of competitive markets, also in the electricity sector, mainly through tariff regulation, network access, quality of service standards, the functioning of markets, and the protection of customers (also final customers); funds for its operation do not come from the state budget, but from a contribution from the regulated operators’ income;

- (5)

Energy Services Regulatory Authority in Portugal (Entidade Reguladora dos Serviços Energéticos)—an independent Portuguese administrative unit; the current mission of the ERSE is to regulate the electricity, natural gas and liquefied natural gas markets in Portugal. This body has management autonomy as well as administrative, financial, and technical independence from the Government and carries out its functions taking into account the guiding principles of the national and European energy policy. Its tasks are (a) to promote the competition, efficiency, and rationality of regulated activities in an objective, transparent, non-discriminatory, and fair manner; (b) to set tariffs and prices for electricity and natural gas; (c) to approve and supervise the application of technical regulations; (d) to supervise the functioning of the market; (e) to commission inquiries, investigations, or audits of regulated companies; (f) to punish offenses relating to the National Electricity System (SEN) and the National Natural Gas System (SNGN); (g) to issue opinions on matters falling within its competence at the request of the Government, the Office of Competition Protection, Courts, or others; (h) to promote voluntary arbitration in the resolution of commercial and contractual conflicts; and (i) to promote and disseminate information to consumers;

- (6)

National Energy Commission in Spain (Comisión Nacional de los Mercados y la Competencia)—an independent body operating within the area of operation of the Ministry of Economy and Digital Transformation responsible for maintaining, guaranteeing, and promoting the proper functioning, transparency, and the existence of effective competition and effective regulation in all markets and production sectors.

The analysis of the legal status of regulatory authorities in individual EU Member States shows the increasing number of categories of this kind of entity at the level of national law under this term and the diversity of interpretations that cause multiple concepts of regulatory authority to arise. Belgian law defines this term as a legal entity under public law, operating with a different level of decentralization. Estonia introduced a broad interpretation of the concept of regulatory authority, giving this status to most of the supervisory authorities that are connected to the regulation of the market, including customs and tax authorities. For Cyprus, a regulatory authority is a legal entity under public law, clearly separated from the state and any other public or private body. Similarly, in Hungary, the regulatory authority means a body, operating under public law, legally and functionally separated from other administrative bodies, and exercising the instruments of market regulation. On the other hand, in Portugal, these institutions, established by the Framework Law on Independent Administrative Entities (LQER), are legal entities under public law. They have a status of independent administrative bodies, exercising instruments of regulation of economic activity or the defense of public services, as well as the protection of consumer rights or the guarantee of competition in all participants of the market [

35] (p. 5).

In the Polish administrative model of electricity market regulation, the scope of activities of the President of the ERO in the area of protection of final household customers (consumers) in the retail electricity market mainly includes: (1) the approval and verification of the use of electricity tariffs in terms of compliance with the rules adopted by the legislator, including analyzing and verifying costs assumed by energy suppliers as justified for the calculation of prices and tariff rates; (2) determining the optimal share of fixed costs in the total fees for the provision of transmission and distribution services for particular groups of consumers in tariffs, in cases where it is required to protect the interests of customers; (3) organizing and conducting tenders for (a) selecting sellers ex officio and (b) building new electricity generation capacities and implementing projects reducing the demand for electricity; (4) controlling the level of quality of customer service and, at the customer’s request, compliance with the quality parameters of energy; (5) taking actions to shape, protect, and develop competition in the electricity market, including (a) removing the existing market barriers in the scope of ability of final customers to use the right to change suppliers and (b) ensuring equal treatment of system users by distribution and transmission system operators; (6) describing and publishing information on indices and index prices important for the tariff formation process; (7) publishing data to increase the efficiency of energy use; and (8) undertaking information activities aimed at protecting the legitimate interests of final users, including publishing on the website of the regulation authority information on recurring or fundamental problems resulting with disputes between energy companies and household customers, as well as on the companies against which justified complaints from these consumers regarding these problems have been filed.

Due to the limited scope of the study, not all tasks performed by the regulatory authority in the field of legal protection of final household customers have been mentioned here, but two main categories can be distinguished among them: imperative and informative. From the perspective of these considerations, of particular importance are those in which the regulatory authority exercises its powers, expressed in issuing an administrative decision binding on the parties to the administrative proceedings. Decisions settle the case as to its essence in whole or in part, or otherwise end the proceedings in a given instance. An administrative decision is a unilateral declaration of will of a public administration body, of an imperative nature, issued on the basis of applicable provisions of law, addressed to a specifically indicated entity, with which the authority does not have an organizational or official bond, and defining its legal situation (determining its rights and obligations) in an individually marked case [

36]. In addition to administrative decisions, the President of the ERO may also issue resolutions in the course of the proceedings. As a rule, the resolutions do not determine the essence of the case but relate to individual issues that will arise in the course of the proceedings.

As a consequence, the decisions of the President of the ERO, which affect the rights and obligations of the final household customers, play a mainly protective role, which is expressed in preventing excessive fiscal burden on the consumer (by directly influencing the formation of tariffs), increasing consumer awareness (by enforcing reliable information for final household customers from other market participants), as well as eliminating situations when the consumer is in a compulsory situation, expressed in the restriction of the choice of the entity with which they can conclude a contract for the supply of electricity for the needs of the household.

8. Judicial Control of the Decisions of the Regulatory Authority

A unique feature of the system of legal measures, which is also important for the legal protection of consumers (final household customers), is the combination of imperative administrative and legal measures with legal measures embedded in the civil procedural law and regulated in the Code of Civil Procedure [

37] (hereinafter referred to as CCP). A common feature of cases related to energy regulation, as well as other regulatory cases, is their normative basis in regulations of public law, establishing legal instruments used by the state to control economic transactions. Therefore, this category of cases is classified as civil cases in a formal sense, due to the attribution to the jurisdiction of civil courts, despite the lack of unambiguous features characteristic of civil law relations (e.g., in cases related to energy regulation, it is not allowed to submit pecuniary claims for interest in an appeal to the court) [

38]. In order to organize these considerations, it should be added that the Court of Protection does not have the exclusive right to verify the proceedings of the President of the ERO. This pertains to the failure to act of the President of the ERO and the excessive length of the proceedings conducted by this body, which is beyond the scope of the civil court’s jurisdiction. It is necessary to agree with A. Cudak that the dualism of jurisdiction of the administrative court and the Court of Protection in relation to the President of the ERO should be assessed negatively. The situation, in which the same case may be adjudicated by an administrative court hearing a complaint on the failure to act or excessive length of proceedings, and the Court of Protection, examining an appeal against a decision of the President of the ERO or a complaint against the decision of this body, is not a desirable state [

39].

The proceedings on appeal against the decision of the President of the ERO is conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Code of Civil Procedure on proceedings in matters related to energy regulation (Part One, Book One, Title VII “Separate Proceedings”, Section IVc of this Code). This solution is of unique nature, which results from the interpenetration of public law aspects of competition protection and collective consumer interests as well as civil law aspects of legal protection of individual and group final household customers. This special solution was introduced by the Polish legislator in the early 1990s, when, after the overthrow of the communist system, legal structures were introduced that were characteristic of countries concerned with the protection of free competition and the protection of weaker entities on the market—consumers, in this case, final household customers.

Pursuant to Art. 30, paragraphs 2–4 of the Energy Law Act, the decision of the regulatory authority (the President of the ERO) may be appealed against to the Court of Protection within two weeks of the date of delivery of the decision. The two-week time limit for lodging an appeal is statutory, which means that it cannot be extended either as a result of a legal action of a party or a court decision. However, this time limit may be reinstated by the court (Art. 168–172 of CCP). According to Art. 479(47) paragraph 2 of CCP, the Court of Protection rejects an appeal lodged after the time limit or that is inadmissible for other reasons, as well as an appeal whose formal defects have not been removed by the party within the prescribed period [

40].

In this case, the judiciary function is performed by the 17th Division of the Regional Court in Warsaw, appointed to hear in court proceedings cases related to counteracting activities restricting free competition and energy regulation. There is no doubt that this court is a common, civil court, and not a special administrative court [

41]. The regulation of Art. 30 paragraph 2 of the Energy Law Act is supplemented by Art. 479(47) paragraph 1 of CCP, which provides that an appeal against the decision of the President of the ERO is lodged through the Office, which, on the one hand, allows for the self-control of the decision by the President of the ERO (Art. 479(48) paragraph 2 of CCP), and on the other hand enables the transfer of the case files kept by the President of the ERO together with the appeal (Art. 479(48) paragraph 1 of CCP) [

25].

The provision of Art. 30 of the Energy Law Act does not contain a catalog of decisions subject to appeal to a civil court. Thus, it should be assumed that it may be lodged against any decision of the President of the ERO, so also against decisions issued in cases for annulment of decisions, in cases for resuming administrative proceedings, as well as against decisions issued as a consequence of the repeal or amendment of the final decision. Therefore, each decision of the President of the ERO is subject to appeal to the Court of Protection and cannot be revoked by other means of legal protection [

42].

The appeal proceedings, combining administrative and civil law elements, was constructed in such a way as to allow the regulatory authority to re-verify its decision and possibly modify its content, as part of the so-called self-control of the authority issuing the decision. At this stage of the proceedings, the President of the ERO, who issued the decision, reconsiders the case, and examines the possibility of changing the position of the authority. In this case, the President of the ERO must take a position on the content of the appeal, and on that basis may determine that: (1) the appeal is well-founded in its entirety (i.e., justified); (2) the appeal of a party may be upheld in its entirety, although it concerns the decision only partially; or (3) the appeal is unfounded [

25]. In the first two situations, the authority of the first instance is sufficient to issue a new decision in which it will repeal or amend the contested decision, while in the last case, it is obliged to send an appeal to the court [

43]. If the appeal is found to be justified, the President of the ERO may, without submitting the file to the court, repeal or amend the decision in whole or in part, of which the party will be immediately notified by sending a new decision, which the party may appeal against. The repeal of the decision and issuance of a new one by the President of the ERO is legally grounded in the content of Art. 479(29) paragraph 2 of CCP [

44]. As clearly indicated in the literature, pursuant to Art. 479(49) of CCP, the appeal should include, inter alia, an application for the repeal or amendment of the decision in whole or in part, and therefore, if a party requests the repeal of the contested decision in its entirety, the President of the ERO may not find the appeal to be only partially justified and only in this respect repeal or amend the contested decision. Likewise, an appeal in which a party requests the repeal or amendment of the decision in part can be considered justified only to the extent requested by the party, and therefore, the President of the ERO may not repeal or amend the contested decision in its entirety. Therefore, under Art. 479(47) paragraph 2 of CCP, the President of the ERO is not entitled to repeal or amend the decision in part when it is appealed against in full, or to amend or repeal the decision in part if it is appealed against in part, but the President of the ERO can uphold the appeal only in (narrower) part, in the sense that only some of the pleas raised in the appeal are considered justified. This means also that the President of the ERO is not entitled to assess the decision in the part not contested by the party and to make any decisions in this regard [

45]. Importantly, as part of the self-control institution, the President of the ERO or an employee of the ERO who participated in the issuance of the decision (the resolution) appealed against to the Court of Protection is not excluded from participation in the issuance of a decision (resolution) to repeal or amend the decision pursuant to Art. 479(48) paragraph 2 of CCP [

46].

Only the President of the ERO as the authority that issued the administrative decision, which is the subject of the legal proceedings, can be the defendant in these cases. Before the Court of Protection, the proxy of the President of the ERO may be an employee of the ERO (Art. 479(51) of CCP). The extension of the group of persons who can act as proxies does not apply to parties to the proceedings other than the President of the ERO. In this category of cases, the appellant is the plaintiff. However, the electricity consumer is not a party to the tariff approval proceedings, and therefore cannot appeal against the decision of the President of the ERO approving the tariff. The appeal of a consumer is inadmissible and subject to rejection [

47].

In matters related to energy regulation, an interested party also appears. The interested party is the one whose rights or obligations depend on the outcome of the trial. If the interested party has not been summoned to participate in the case, the Court of Protection will summon them at the request of the party or ex officio (Art. 479(50) paragraph 2 of CCP). The procedural situation of the interested party, who did not take part in the case and is summoned to it at the request of a party or ex officio by a court is unclear [

48]. In the literature, the interested party is either given a role of a separate, independent party to the proceedings or a special secondary intervenient, or it is stated that the legal interest of the interested party fulfils the function of a standing to institute proceedings or participate in them [

49].

If a non-governmental organization has been admitted as a party to the proceedings before the President of the ERO, it also has the right to lodge an appeal to the court [

50]. It seems that in relation to matters directly related to the rights and obligations of final household customers, the procedural role of non-governmental organizations, whose statutory tasks include the protection of consumer rights, these cases are of particular importance. In practice, consumers often turn to consumer organizations for substantive support in disputes with energy companies in order to eliminate their economic and substantive advantage resulting from the specificity of this market.

What is particularly interesting in this category of cases is that the legislator provides for the possibility of the parties, i.e., the President of the ERO on the one hand and the party (parties) to the proceedings before the President of the ERO on the other hand, to conclude a settlement regarding an appeal to the Court of Protection. Pursuant to Art. 479(52a) in connection with Art. 479(30a) of CCP, a solution was adopted under which, in matters relating to energy regulation being the subject of an appeal against the decision of the President of the ERO to the Court of Protection, the parties may reach a settlement on the subject of the contested decision of the President of the ERO in whole or in part. The settlement is to be an alternative to the judgment as a way of ending the case that was brought to court as a result of a complaint. The parties have a wider range of possibilities at their disposal than the court (e.g., withdrawal of the appeal by the complainant). A settlement may be concluded in the course of both the proceedings initiated by the complaint and the appeal proceedings. The subject of the settlement is therefore the resolution of the case, within the limits permitted by the relevant provisions of substantive law and procedural law.

On the basis of the approved settlement, the regulatory authority repeals or amends the contested decision or performs other action, depending on the circumstances of the case, within its jurisdiction and competence. The court refuses to approve a settlement on appeal to the Court of Protection, in whole or in part, if it is inconsistent with the law or the principles of social coexistence or aims to circumvent the law, and also when it is incomprehensible or contains contradictions (Art. 479(30c) paragraph 3 of CCP). Interestingly, the legislator does not rule out partial approval of a settlement and partial refusal to approve it. If the settlement has been approved, the Court of Protection discontinues the proceedings to the extent covered by the settlement (Art. 479(30d) paragraph 1 of CCP).

It is worth paying attention to the specificity of court decisions in the discussed category of cases. In the case of an appeal against a decision of the regulatory authority, the court: (1) dismisses the appeal if it is unfounded (Art. 479(53) paragraph 1 of CCP); (2) upholds the appeal and repeals the contested decision or amends it in whole or in part, and adjudicates on the merits of the case (Art. 479(53) paragraph 2 of CCP); (3) rejects the appeal if it was lodged after the time limit for lodging it, is inadmissible for other reasons, or if its deficiencies have not been removed within the prescribed period (Art. 479(47) paragraph 2 of CCP); and (4) discontinues the proceedings, e.g., in the event of an effective withdrawal of an appeal against the decision of the President of the ERO [

51] or on the principles set out in the Code of Civil Procedure. However, the civil court has no legal grounds to issue a judgment amending the contested decision by discontinuing administrative proceedings, as this type of decision has not been provided for in Art. 479(53) paragraph 2 of CCP. The discontinuation of administrative proceedings is not a ruling on the merits of the case, but only a ruling concluding the proceedings in the case; the Court of Protection is not entitled to issue a judgment of this content, and if the administrative proceedings are unsubstantiated, it should repeal the contested decision [

52]. There is no doubt, however, that after the decision is repealed by the Court of Protection, the President of the ERO may conduct new administrative proceedings and issue a new decision [

53].

Due to the fact that the Court of Protection acts as a court of first instance, its judgment is subject to appeal under general rules. In this category of cases, an extraordinary means of appeal is available, which is a cassation appeal to the Supreme Court, against a decision of a second instance court (court of appeal) in matters related to energy regulation, regardless of the value of the subject of the appeal (Art. 479(67) paragraph 2 of CCP).

The aforementioned regulations make the procedural structure used in cases related to energy regulation an original solution, which combines essential elements of one-instance administrative proceedings and two-instance civil proceedings with the possibility of using the civil procedural extraordinary means of appeal. Such a solution allows for the effective use of civil procedural instruments based on the principle of equality of the parties for the protection of consumer rights, the civil law nature of which remains indisputable.

9. Discussion and Conclusions

On the basis of these considerations, one should agree with the position expressed in the doctrine, as electrical energy is an essential input into middle and final consumption, and its real price and quality of supply are critical for production fees, competitiveness of the economy, and standard of living. It should be emphasized that energy markets in the past were usually monopolized by local entities; the objective of the opening and liberalization of the energy markets in Europe is to induce and to encourage market forces and restructuring towards more developed market transactions with the elimination of crucial inefficiencies, and to establish competitive supply of energy to final household customers [

54] (p. 24).

Summarizing the above legal analyses, it should be noted that the Polish model of protection of consumer rights has a mixed character, combining civil and administrative elements, for which the following conclusions can be drawn:

- (1)

The protection of the collective interests of final household customers in the retail electricity market, according to the views of the doctrine, is an area of administrative and legal regulation, resulting primarily from the need to use by the regulatory authority instruments related to the statutory powers—administrative decisions as decisions on the merits and formal resolutions;

- (2)

The protection of group (which should not be confused with collective) and individual consumer rights is based on civil law structures resulting from the provisions of the Polish Civil Code, and reinforced with the structures of the Code of Civil Procedure, which also provide consumers with a privileged legal status;

- (3)

In terms of procedural regulations, a characteristic feature of the Polish legal structure, crucial for the protection of consumer rights, was the introduction of the stage of proceedings based on civil procedural solutions, instead of maintaining the continuity of administrative and court-administrative proceedings in matters of protection of collective consumer interests.

Consequently, it should be assumed that this is a hybrid model of protection that combines two legal regimes.

At the same time, an important conclusion resulting from the practice of applying the above-mentioned provisions to various aspects of regulation of the retail electricity market is that the hybrid nature of this solution—next to its undoubted efficiency—results in interpretation problems.

This refers, in particular, to the duality of appealing against the actions of the President of the ERO as a regulatory authority, since the civil court has the right to hear appeals against administrative decisions important for regulating the electricity market and appeals against decisions as formal decisions concerning the course of administrative proceedings, it is inconsistent to assign the problem of failure to act of a body and excessive length of proceedings before the President of the ERO to the administrative procedure. However, the lack of a clear indication of this scope of the jurisdiction of the civil court in the Code of Civil Procedure means that, in this case, general rules of administrative proceedings relating to the verification of activities of public administration bodies should be applied.

To sum up, participants of the retail electricity market, in particular, final household customers, have significant problems with determining the correct course of pursuing their claims, due to the duality of the Polish structure, which is not always reinforced with a precise definition of the jurisdiction of individual administrative and judicial bodies.

This solution differs from the classic solutions in other EU Member States, where the separation of administrative and civil law disciplines is clearer. In Germany, the distinction between administrative and civil courts occurs depending on the type of matter related to regulation: cases concerning the regulation of energy are heard within a system of ordinary civil courts and Federal Court of Justice (the Bundesgerichtshof) as court of last instance. The federal law has introduced this distinction between administrative and civil courts based on Section 75(4) EnWG (Energy Industry Act, Energiewirtschaftsgesetz). This specific regulation concerns cases related to regulation energy markets and passes them to the higher regional courts. Those courts are higher level of the civil courts (Oberlandesgerichte) [

55]. However, in Italy, the legislator granted to administrative courts jurisdiction over all cases considering those acts of the independent administrative authorities. This jurisdiction covers rulemaking, adjudication, and individual, general, or sanctioning acts. This also concerns regulations of energy markets [

56]. Similarly, in the Portuguese legal system, there is a distinction of jurisdiction related to administrative acts of those authorities, whether it pertains to mere administrative offences, irrespective of the character and field of issued act. Consequently, disputes that concern regulatory matters, as a rule, should be resolved in the administrative courts on the same ground [

57]. Additionally, in Spain, the Law on Administrative Jurisdiction 29/1998 establishes that appeals against administrative acts issued by regulatory and supervisory authorities are heard by the Administrative Chamber of the National High Court (Audiencia Nacional). However, the Supreme Court hears appeals in cassation against the decisions of the Audiencia Nacional [

58].

Consequently, an interesting, atypical Polish combination of administrative, legal, and civil procedural elements for over 30 years of operation and improvement meets the criteria of an effective protective tool, which, however, requires clarification in those aspects in which the legislator has shown inconsistency in the regulations, creating legal gaps that need to be supplemented by applying general legal structures of administrative law. Such an approach weakens the effectiveness of civil procedural protective instruments, which, by their nature, are closer to the idea of protecting the rights of the consumer as a weaker entity in relations with other professional participants of the electricity market. However, this does not change the positive assessment of the Polish model of protecting the collective interests of final household customers, which may be an example for countries that are just shaping their approach to an effective model of legal protection of final household customers, including vulnerable customers, as weaker participants in the retail electricity market.