Energy Conservation and Firm Performance in Thailand: Comparison between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. Energy Conservation in Thailand

2.2. Theoretical Framework

2.2.1. Stakeholder Theory

2.2.2. Legitimacy Theory

2.3. Energy Conservation between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries

2.4. Energy Conservation and Firm Performance

3. Methods

3.1. Population and Samples

3.2. Data Collection

3.3. Variable Measurement

3.4. Data Analysis

4. Results and Discussion

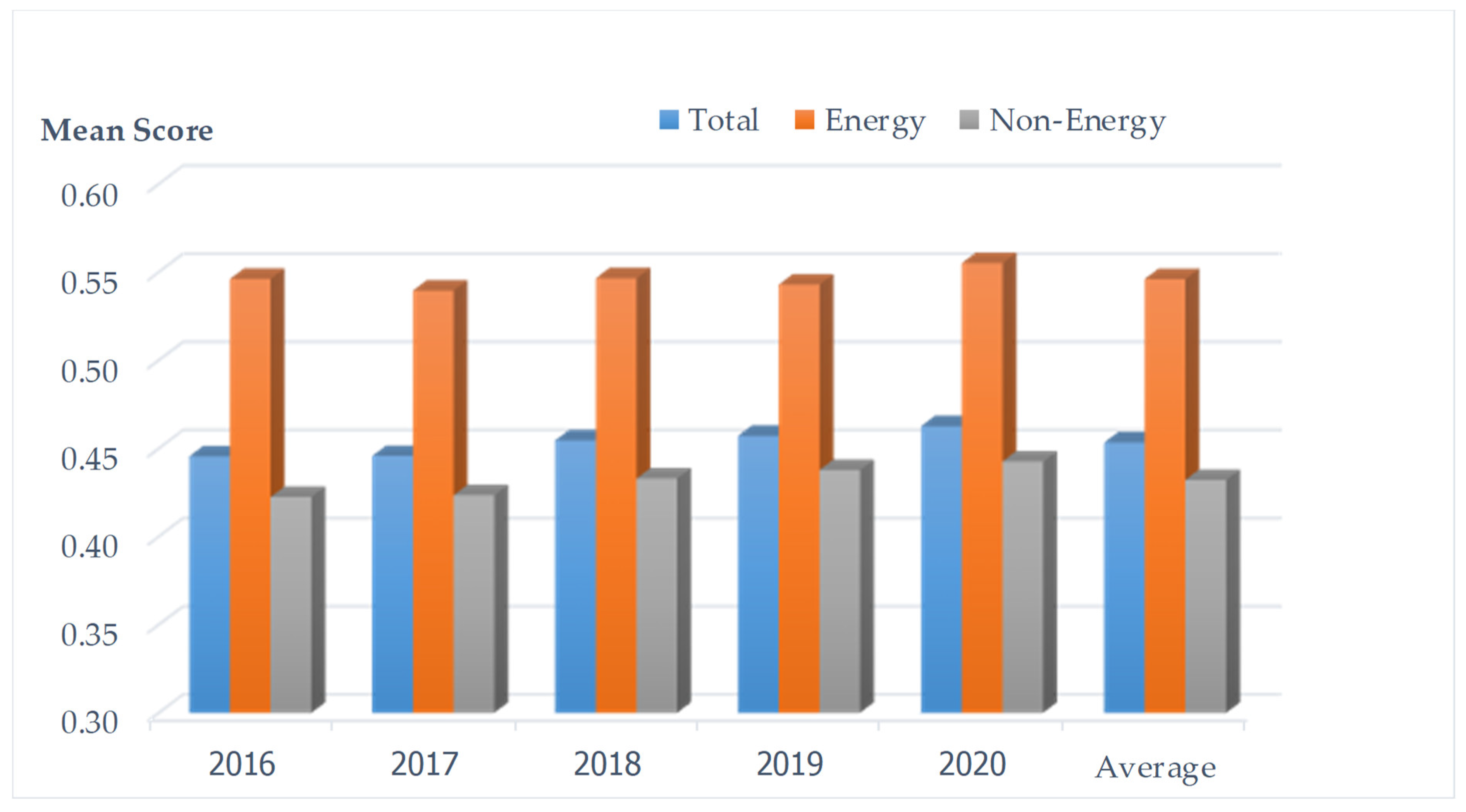

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Correlation Analysis

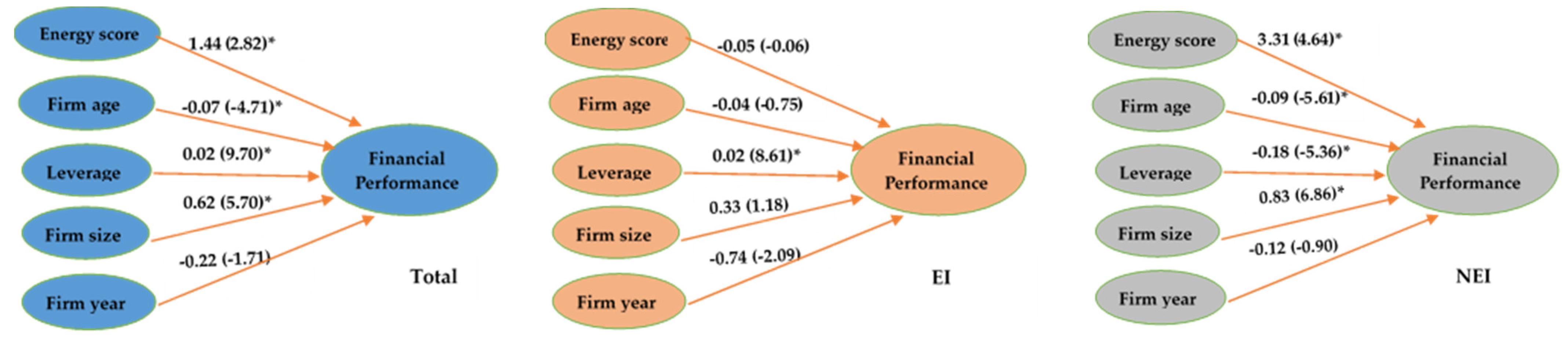

4.3. Regression Analysis

4.4. Robustness Test

5. Conclusions

6. Contributions and Implications

7. Limitations and Suggestions for Future Study

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Suttipun, M.; Duriyarattakan, S. The Influence of Energy Management on Thai Manufaturing Firms Performance. Manag. Res. Pract. 2019, 11, 52–61. [Google Scholar]

- Akbas, H.E.; Canikli, S. Corporate Environmental Disclosures in a Developing Country: An Investigation on Turkish Listed Companies. Int. J. Econ. Financ. 2014, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallardo-Vázquez, D.; Barroso-Méndez, M.J.; Pajuelo-Moreno, M.L.; Sánchez-Meca, J. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure and Performance: A Meta-Analytic Approach. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasrip, N.E.; Husin, N.M.; Alrazi, B. The Energy Disclosure Among Energy Intensive Companies in Malaysia: A Resource Based Approach. SHS Web Conf. EDP Sci. 2017, 36, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Lai, K.-H. Mediating effect of managers' environmental concern: Bridge between external pressures and firms' practices of energy conservation in China. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 43, 203–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tasneem, F.; Muhammad, S.; Basit, A. The Impact of Environmental Reporting on Firms’ Performance. Int. J. Account. Bus. Manag. 2016, 4, 275–300. [Google Scholar]

- Klimontowicz, M.; Losa-Jonczyk, A.; Zacny, B. Banks’ Energy Behavior: Impacts of the Disparity in the Quality and Quantity of the Disclosures. Energies 2021, 14, 7325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M.; Blass, V.D. Measuring corporate environmental performance: The trade-offs of sustainability ratings. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2010, 19, 245–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasothorn, A.; Teekasap, P.; Teekasap, S. Energy conservation direction and economic growth. J. Renew. Energy Smart Grid Technol. 2017, 12, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Supasa, T.; Hsiau, S.-S.; Lin, S.-M.; Wongsapai, W.; Wu, J.-C. Has energy conservation been an effective policy for Thailand? An input–output structural decomposition analysis from 1995 to 2010. Energy Policy 2016, 98, 210–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intarajinda, R.; Bhasaputra, P. Thailand’s energy conservation policy for industrial sector considering government incentive measures. GMSARN Int. J. 2012, 6, 67–78. [Google Scholar]

- Traivivatana, S.; Wangjiraniran, W. Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint (TIEB): One Step towards Sustainable Energy Sector. Energy Procedia 2019, 157, 492–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M. The influence of board composition on environmental, social and governance (ESG) disclosure of Thai listed companies. Int. J. Discl. Gov. 2021, 18, 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET). Company Listed in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. 2020. Available online: http://www.set.or.th. (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Orapin, W. The Corporate Social Responsibility Data Disclosure of the Companies in Stock Exchange of Thailand. J. Grad. Sch. Pitchayatat 2019, 14, 195–203. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Energy Efficiency and Firm Performance: Evidence from Swedish Industry. Ph.D. Thesis, Department of Forest Economics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Uppsala, Sweden, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, W.; Xing, K. Linking Environmental and Financial Performance for Privately Owned Firms: Some Evidence from Australia. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2016, 56, 330–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jindakun, S. Corporate Social Responsibility Reporting: A Comparative Study of Com-panies in the Stock Exchange of Thailand (SET) between Industrial and Services Industries. Master’s Thesis, Prince of Songkla University, Faculty of Management Sciences, Accountancy, Hat Yai, Thailand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cho, C.H.; Guidry, R.P.; Hageman, A.M.; Patten, D.M. Do actions speak louder than words? An empirical investigation of corporate environmental reputation. Account. Organ. Soc. 2012, 37, 14–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dragomir, V.D. Environmentally sensitive disclosures and financial performance in a European setting. J. Account. Organ. Chang. 2010, 6, 359–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C.; Gordon, B. A Study of the Environmental Disclosure Practices of Aus-tralian Corporations. Account. Bus. Res. 1996, 26, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frost, G.; Wilmshurst, T. The Adoption of Environment-Related Management Ac-counting: An Analysis of Corporate Environmental Sensitivity. Accounting Forum. 2000, 24, 344–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, W.; Zhu, N.; Zhang, J. The Impact of Carbon Disclosure on Financial Performance under Low Carbon Constraints. Energies 2021, 14, 4126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dan, E.; Shen, J. Establishment of Corporate Energy Management Systems and Voluntary Carbon Information Disclosure in Chinese Listed Companies: The Moderating Role of Corporate Leaders’ Low-Carbon Awareness. Sustainability 2022, 14, 2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Energy Outlook. World Energy and Economic Outlook. 2022. Available online: https://www.iea.org/reports/southeast-asia-energy-outlook-2022 (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Energy Policy and Planning Office. Thailand Power Development Plan. 2016. Available online: http://www.eppo.go.th/index.php/en/policy-and-plan/en-tieb/tieb-pdp (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Thephakum, P. Corporate Social Responsibility Disclosure of Environmental, Social and Governance Companies. Master’s Thesis, Chiang Mai University, School of Business, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Thaipat Institute. ESG Rating Report. 2017. Available online: https://www.thaipat.org/2018/05/esg-report.html (accessed on 15 August 2022).

- Drucker, P.F. Management: Tasks, Responsibilities, Practices. In Truman Talley Books; E.P. Dutton: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, G.F.; Romi, A.M. Discretionary compliance with mandatory environmental disclosures: Evidence from SEC filings. J. Account. Public Policy 2013, 32, 213–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, J.; Tian, Z. Research on Mandatory Disclosure of Executive Salary of Listed Companies. J. Xiamen Univ. Arts Soc. Sci. 2012, 3, 34–41. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts, R.W. Determinants of corporate social responsibility disclosure: An application of stakeholder theory. Account. Organ. Soc. 1992, 17, 595–612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borghei, Z.; Leung, P.; Guthrie, J. The nature of voluntary greenhouse gas disclosure—An explanation of the changing rationale: Australian evidence. Meditari Accountancy Research. 2016, 24, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T.; Preston, L.E. The Stakeholder Theory of the Corporation: Concepts, Evidence, and Implications. Acad. Manag. Rev. 1995, 20, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jawahar, I.M.; McLaughlin, G.L. Toward a Descriptive Stakeholder Theory: An Organizational Life Cycle Approach. Acad. Manag. Rev. 2001, 26, 397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouckaert, L.; Vandenhove, J. Business ethics and the management of nonprofit institutions. J. Bus. Ethics 1998, 17, 1073–1081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R.E.; McVea, J. A Stakeholder Approach to Strategic Management. In The Blackwell Handbook of Strategic Management; Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK, 2005; pp. 183–201. [Google Scholar]

- Deegan, C. Introduction: The Legitimising Effect of Social and Environmental Disclosures—A Theoretical Foundation. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2002, 15, 282–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neu, D.; Warsame, H.; Pedwell, K. Managing public impressions: Environmental dis-closures in annual reports. Account. Organ. Soc. 1998, 23, 265–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deegan, C. Organizational legitimacy as a motive for sustainability reporting. In Sustainability Accounting and Accountability; Routledge: London, UK, 2010; pp. 146–168. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Z.; Peng, J.; Tang, Q. A Comparative Study of Mandatory and Voluntary Carbon Information Disclosure Systems: Experiences from China’s Capital Market. J. Syst. Manag. 2018, 27, 452–461. [Google Scholar]

- Pellegrino, C.; Lodhia, S. Climate change accounting and the Australian mining industry: Exploring the links between corporate disclosure and the generation of legitimacy. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 36, 68–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patten, D.M. Exposure, legitimacy, and social disclosure. J. Account. Public Policy 1991, 10, 297–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasanbeigi, A.; Menke, C.; Du Pont, P. Barriers to energy efficiency improvement and decision-making behavior in Thai industry. Energy Effic. 2009, 3, 33–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratanajongkol, S.; Davey, H.; Low, M. Corporate social reporting in Thailand: The news is all good and increasing. Qual. Res. Account. Manag. 2006, 3, 67–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thephakum, P. Corporate social responsibility disclosure of environmental, social and governance. AccBa J. Chiang Mai Univ. 2020, 6, 130–136. [Google Scholar]

- Pintea, M.-O.; Stanca, L.; Achim, S.-A.; Pop, I. Is there a Connection among Environmental and Financial Performance of a Company in Developing Countries? Evidence from Romania. Procedia Econ. Financ. 2014, 15, 822–829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suttipun, M.; Sittidate, N. Corporate social responsibility reporting and operation performance of listed companies in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. Songklanakarin J. Soc. Sci. Humanit. 2016, 22, 269–295. [Google Scholar]

- Suttipun, M.; Srirat, T.; Samang, N.; Manae, N.; Maithong, A. The Influences of Corporate Social Responsibility on Firm Performance Measured by Balanced Scorecard: An Evidence of Hotel in Thailand's Southern Border Provinces. ABAC ODI J. Vision. Action. Outcome 2018, 5, 97–113. [Google Scholar]

- Endrikat, J.; Guenther, E.; Hoppe, H. Making sense of conflicting empirical findings: A meta-analytic review of the relationship between corporate environmental and financial performance. Eur. Manag. J. 2014, 32, 735–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günther, E.; Hoppe, H.; Endrikat, J. Corporate financial performance and corporate environmental performance: A perfect match? Zeitschrift Für Umweltpolitik Umweltrecht 2011, 3, 279–296. [Google Scholar]

- Friede, G.; Busch, T.; Bassen, A. ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. J. Sustain. Financ. Invest. 2015, 5, 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixon-Fowler, H.R.; Slater, D.J.; Johnson, J.L.; Ellstrand, A.E.; Romi, A.M. Beyond “Does it Pay to be Green?” A Meta-Analysis of Moderators of the CEP-CFP Relationship. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 112, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertini, E. Does Environmental Management Improve Financial Performance? A Meta-Analytical Review. Organ. Environ. 2013, 26, 431–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez-Calderón, E.; Milanés-Montero, P.; Ortega-Rossell, F.J. Environmental perfor-mance and firm value: Evidence from Dow Jones Sustainability Index Europe. Int. J. Environ. Res. 2012, 6, 1007–1014. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, W.-L.; Cheah, J.-H.; Azali, M.; Ho, J.A.; Yip, N. Does firm size matter? Evidence on the impact of the green innovation strategy on corporate financial performance in the automotive sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 974–988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, L.W.; Pan, S.J.; Liu, G.Q.; Zhou, P. Does energy efficiency affect financial performance? Evidence from Chinese energy-intensive firms. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 151, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Ngniatedema, T.; Chen, F. Understanding the Impact of Green Initiatives and Green Performance on Financial Performance in the US. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2017, 26, 776–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chlyeh, D. The Impact of Renewable Energy Performance on Corporate Financial Performance. Master’s Thesis, İbn Haldun Üniversitesi, Lisansüstü Eğitim Enstitüsü,, Başakşehir, Turkey, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Suttipun, M. Association between board composition and intellectual capital disclosure: An evidence from Thailand. J. Bus. Adm. 2018, 41, 74–97. [Google Scholar]

- Aguilera-Caracuel, J.; Hurtado-Torres, N.E.; Aragón-Correa, J.A. Does international experience help firms to be green? A knowledge-based view of how international experience and organisational learning influence proactive environmental strategies. Int. Bus. Rev. 2011, 21, 847–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Wang, Z.; Yin, J.; Su, L. CO2 emission reduction within Chinese iron steel industry: Practices, determinants and performance. J. Clean. Prod. 2012, 33, 167–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullah, F.B.; Iqbal, R.; Ahmad, S.; El-Affendi, M.A.; Kumar, P. Optimization of Multidimensional Energy Security: An Index Based. Energies 2022, 15, 3929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, J.; Abeysekera, I. Content analysis of social, environmental reporting: What is new? J. Hum. Resour. Costing Account. 2006, 10, 114–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piesiewicz, M.; Ciechan-Kujawa, M.; Kufel, P. Differences in Disclosure of Integrated Reports at Energy and Non-Energy Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, G.; Zeng, S.; Shi, J.J.; Meng, X.; Lin, H.; Yang, Q. Revisiting the relationship between environmental and financial performance in Chinese industry. J. Environ. Manag. 2014, 145, 349–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baran, M.; Kuźniarska, A.; Makieła, Z.J.; Sławik, A.; Stuss, M.M. Does ESG Reporting Relate to Corporate Financial Performance in the Context of the Energy Sector Transformation? Evidence from Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buallay, A.; Hamdan, A.; Zureigat, Q. Corporate governance and firm performance: Evidence from Saudi Arabia. Australas. Account. Bus. Financ. J. 2017, 11, 78–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kludacz-Alessandri, M.; Cygańska, M. Corporate Social Responsibility and Financial Performance among Energy Sector Companies. Energies 2021, 14, 6068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hodkam, S. The Study of Relationship between the Level of Sustainability Report Disclosure and Security Prices of Listed Companies in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. Master’s Thesis, Burapha University, Saen Suk, Thailand, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Huaypad, S. The Relationship between the Quality of Social Responsibility Disclosure and Stock Price of Firms Listed in the Stock Exchange of Thailand. J. Mod. Manag. Sci. 2019, 12, 53–67. [Google Scholar]

- Horváthová, E. The impact of environmental performance on firm performance: Short-term costs and long-term benefits? Ecol. Econ. 2012, 84, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Innovation | 1. R&D investment in energy-saving technology |

| 2. Retrofit the production process for energy-saving | |

| 3. Replacing equipment with energy-efficient equipment | |

| 4. Budgeting for energy conservation or efficiency | |

| Residue recycling | 5. Recycling residual energy |

| 6. Recycling waste material and by-products | |

| Carbon Emission | 7. Carbon reduction |

| 8. Carbon emission in operation | |

| Energy conservation strategy | 9. Short-term objective for energy conservation in the firm |

| 10. Long-term vision for how to reduce energy consumption in the firm | |

| 11. Clear plan for how to conduct energy conservation activities | |

| Implementation in operation | 12. Systematic control of energy consumption in the production process and management |

| 13. Awareness building concerning energy conservation |

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Notation | Measurement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable | Financial performance | ROA | Return on assets (ROA) |

| Independent Variable | Energy score | ECS | Score of energy conservation |

| Firm age | AGE | Year of firm age | |

| Leverage | LEV | Debt to equity ratio | |

| Control Variable | Firm size | SIZE | Natural logarithm of total assets |

| Firm year | YEAR | Annual report year |

| Score | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | Average |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n Mean (SD) | n Mean (SD) | n Mean (SD) | n Mean (SD) | n Mean (SD) | n Mean (SD) | |

| Total | 647 | 676 | 684 | 705 | 721 | 3433 |

| 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.45 | |

| (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.28) | (0.28) | |

| Energy | 121 | 130 | 130 | 130 | 129 | 640 |

| 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.55 | 0.54 | 0.56 | 0.55 | |

| (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | (0.30) | |

| Non-Energy | 526 | 546 | 554 | 575 | 592 | 2793 |

| 0.42 | 0.42 | 0.43 | 0.44 | 0.44 | 0.43 | |

| (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.27) | (0.27) | |

| Variable | n | Mean | SD | t | Sig. | |

| Energy | 640 | 0.55 | 0.30 | −8.89 | 0.00 | |

| Non-Energy | 2793 | 0.43 | 0.27 |

| Variables | ROA | ECS | AGE | LEV | SIZE | YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 1 | 0.07 ** | −0.06 ** | 0.17 ** | 0.09 ** | −0.04 * |

| ECS | - | 1 | 0.06 ** | 0.05 ** | 0.14 ** | 0.01 |

| AGE | - | - | 1 | 0.01 | 0.19 ** | 0.06 ** |

| LEV | - | - | - | 1 | −0.01 | −0.01 |

| SIZE | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.02 |

| YEAR | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Variables | ROA | ECS | AGE | LEV | SIZE | YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 1 | 0.03 | −0.03 | 0.3 ** | 0.02 | −0.10 ** |

| ECS | - | 1 | −0.01 | 0.06 | 0.10 * | −0.04 |

| AGE | - | - | 1 | 0.05 | −0.15 ** | 0.10 * |

| LEV | - | - | - | 1 | −0.07 | −0.03 |

| SIZE | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.03 |

| YEAR | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Variables | ROA | ECS | AGE | LEV | SIZE | YEAR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ROA | 1 | 0.10 ** | −0.07 ** | −0.09 ** | 0.11 ** | −0.02 |

| ECS | - | 1 | 0.13 ** | 0.01 | 0.15 ** | 0.03 |

| AGE | - | - | 1 | 0.05 * | 0.28 ** | 0.05 ** |

| LEV | - | - | - | 1 | 0.13 ** | −0.01 |

| SIZE | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.02 |

| YEAR | - | - | - | - | - | 1 |

| Variable | Model A (Total) | Model B (EI) | Model C (NEI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t (sig) | B | t (sig) | B | t (sig) | |

| Constant | 567.26 | 1.71 (0.09) | 1901.14 | 2.09 (0.04) | 310.33 | 0.89 (0.04) |

| ECS | 1.44 | 2.82 (0.01 *) | −0.05 | −0.06 (0.96) | 3.31 | 4.64 (0.00 *) |

| AGE | −0.07 | −4.71 (0.00 *) | −0.04 | −0.75 (0.45) | −0.09 | −5.61 (0.00 *) |

| LEV | 0.02 | 9.70 (0.00 *) | 0.02 | 8.61 (0.00 *) | −0.18 | −5.36 (0.00 *) |

| SIZE | 0.62 | 5.70 (0.00 *) | 0.33 | 1.18 (0.24) | 0.83 | 6.86 (0.00 *) |

| YEAR | −0.22 | −1.71 (0.09) | −0.74 | −2.09 (0.04) | −0.12 | −0.90 (0.03) |

| R Square | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.04 | |||

| Adj. R Square | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.04 | |||

| F-value (s) | 31.40 (0.00 *) | 16.20 (0.00 *) | 22.33 (0.00 *) | |||

| n | 3179 | 583 | 2596 | |||

| Variable | Model A (Total) | Model B (EI) | Model C (NEI) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| B | t (sig) | B | t (sig) | B | t (sig) | |

| Constant | 1555.43 | 1.78 (0.08) | 982.50 | 0.44 (0.66) | 1707.64 | 1.80 (0.07) |

| ECS | 2.81 | 2.09 (0.04 *) | 2.25 | 1.10 (0.27) | 4.25 | 2.20 (0.03 *) |

| AGE | −0.04 | −1.10 (0.27) | −0.00 | −0.03 (0.98) | −0.07 | −1.61 (0.11) |

| LEV | −0.01 | −1.07 (0.29) | −0.00 | −0.78 (0.44) | −0.18 | −1.98 (0.05) |

| SIZE | 1.36 | 4.74 (0.00 *) | 1.15 | 1.64 (0.10) | 1.62 | 4.95 (0.00 *) |

| YEAR | −0.61 | −1.79 (0.07) | −0.39 | −0.44 (0.66) | −0.67 | −1.81 (0.07) |

| R Square | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| Adj. R Square | 0.01 | 0.01 | 0.01 | |||

| F-value (s) | 6.86 (0.00 *) | 1.06 (0.38) | 7.48 (0.00 *) | |||

| n | 3172 | 583 | 2589 | |||

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lakkanawanit, P.; Dungtripop, W.; Suttipun, M.; Madi, H. Energy Conservation and Firm Performance in Thailand: Comparison between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries. Energies 2022, 15, 7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207532

Lakkanawanit P, Dungtripop W, Suttipun M, Madi H. Energy Conservation and Firm Performance in Thailand: Comparison between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries. Energies. 2022; 15(20):7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207532

Chicago/Turabian StyleLakkanawanit, Pankaewta, Wilawan Dungtripop, Muttanachai Suttipun, and Hisham Madi. 2022. "Energy Conservation and Firm Performance in Thailand: Comparison between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries" Energies 15, no. 20: 7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207532

APA StyleLakkanawanit, P., Dungtripop, W., Suttipun, M., & Madi, H. (2022). Energy Conservation and Firm Performance in Thailand: Comparison between Energy-Intensive and Non-Energy-Intensive Industries. Energies, 15(20), 7532. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15207532