Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values Comparing Poland and India Aligned with Environment Policy for Sustainable Development

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- -

- To know the importance of green consumer values comparatively between Poland and India.

- -

- To measure the importance level of each decision criteria from green consumer values on different RESs.

- -

- To obtain a comparison of Poland and India on their green consumer values of RESs.

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. Environmental Policy

2.1.1. Europe Adaptation of Environment Policy

2.1.2. Poland—A View towards Environmental Policy

2.1.3. Asia Adaptation of Environment Policy

2.1.4. India—A View towards Environmental Policy

2.2. Sustainable Development

2.3. Green Consumer Values

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Methodological Approach

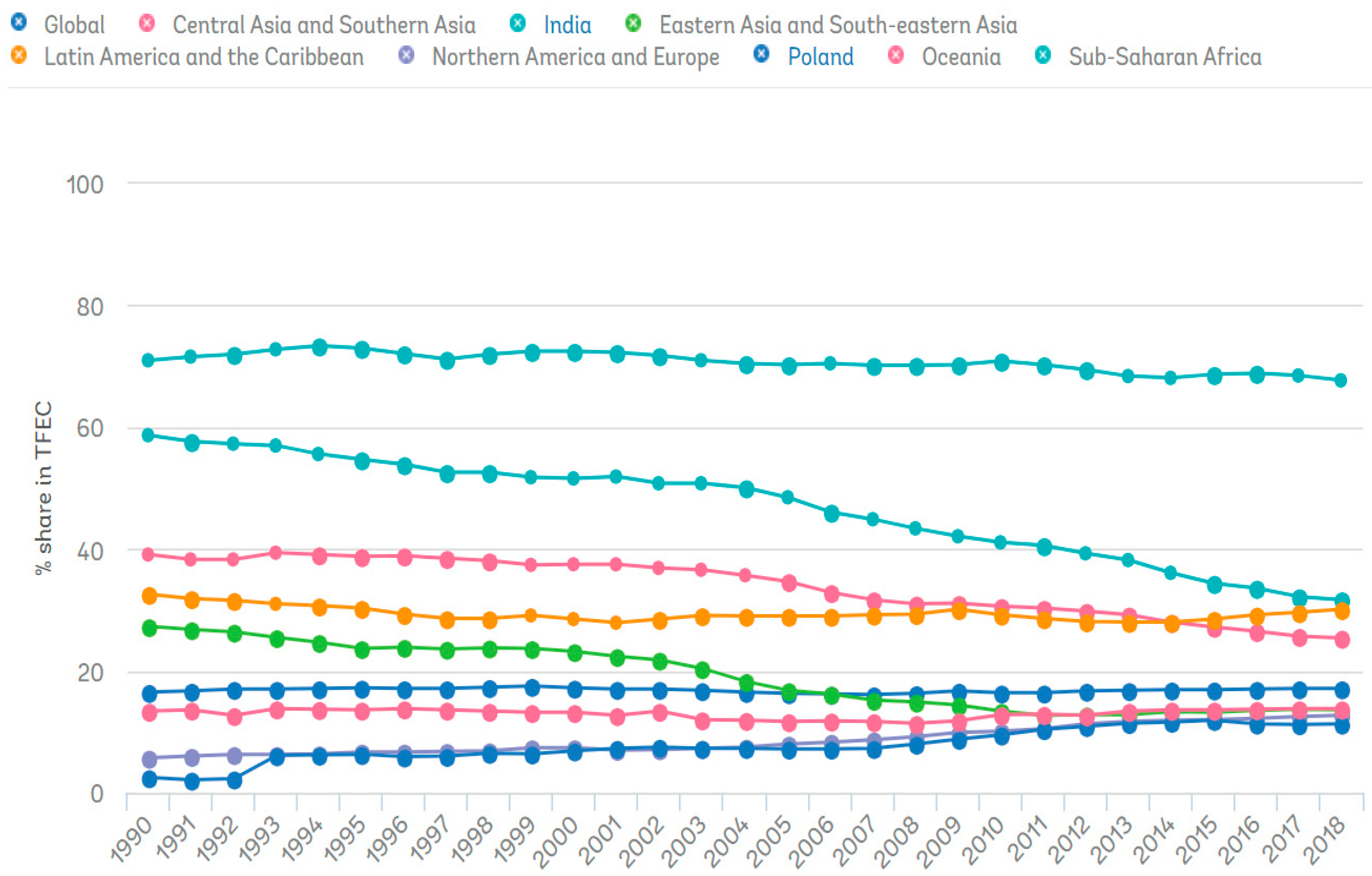

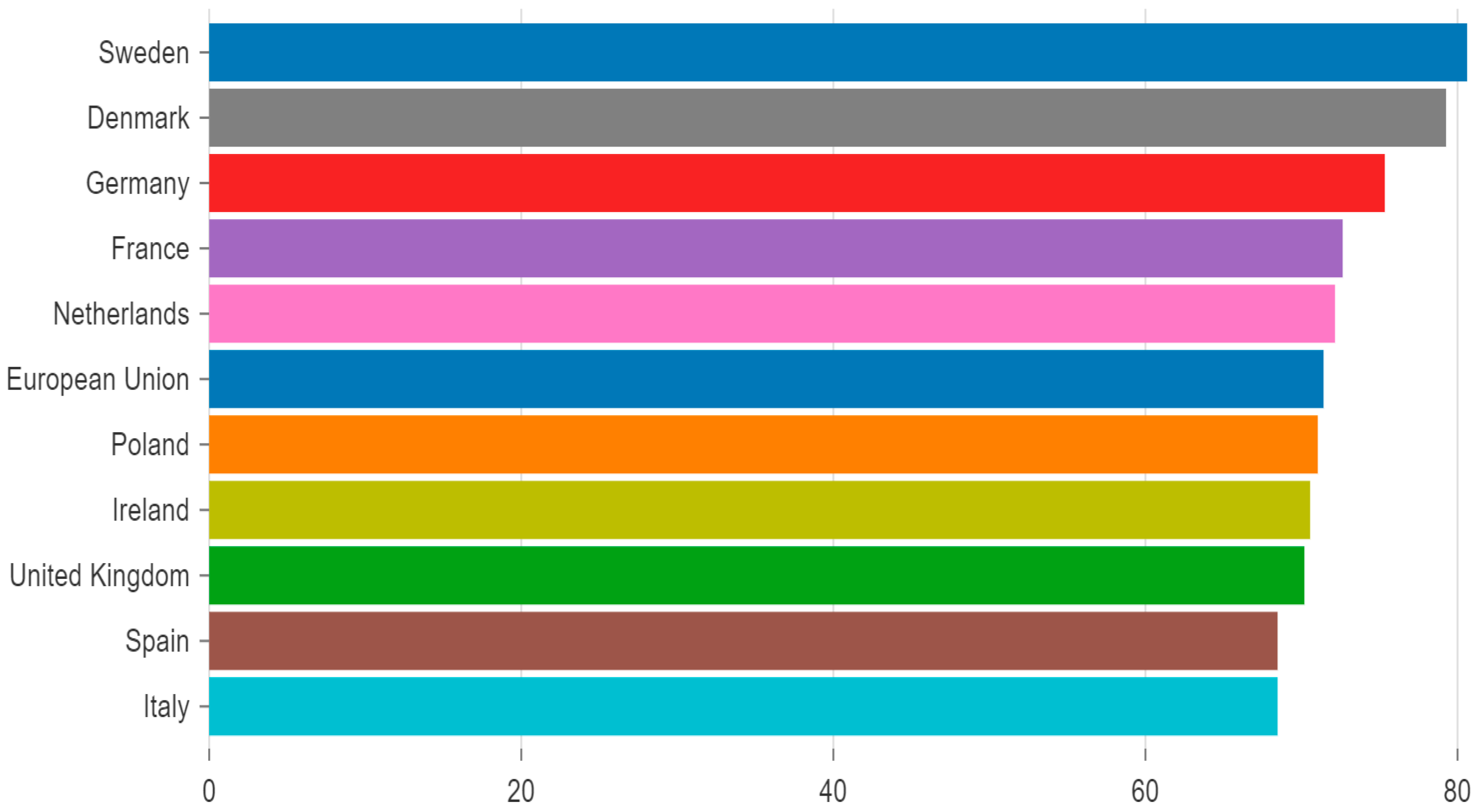

3.2. EU Environmental Policy Implementation for Sustainability Statistics

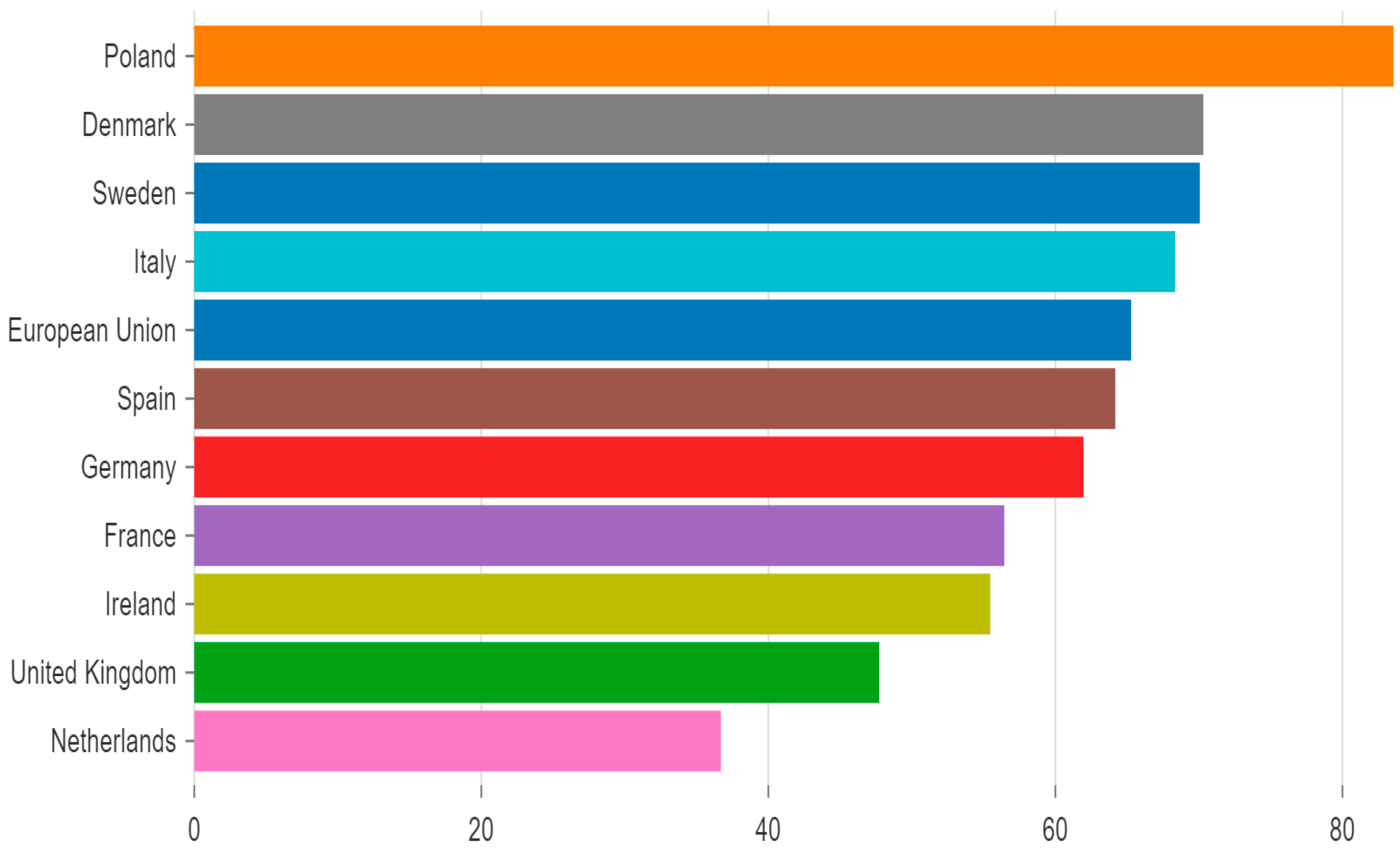

3.3. Poland Environmental Policy Implementation for Sustainability Statistics

3.4. Asia Environmental Policy Implementation for Sustainability Statistics

3.5. India Environmental Policy Implementation for Sustainability Statistics

3.6. Green Consumer Values for Renewable Energy Comparative Data Poland and India

4. Discussion and Results

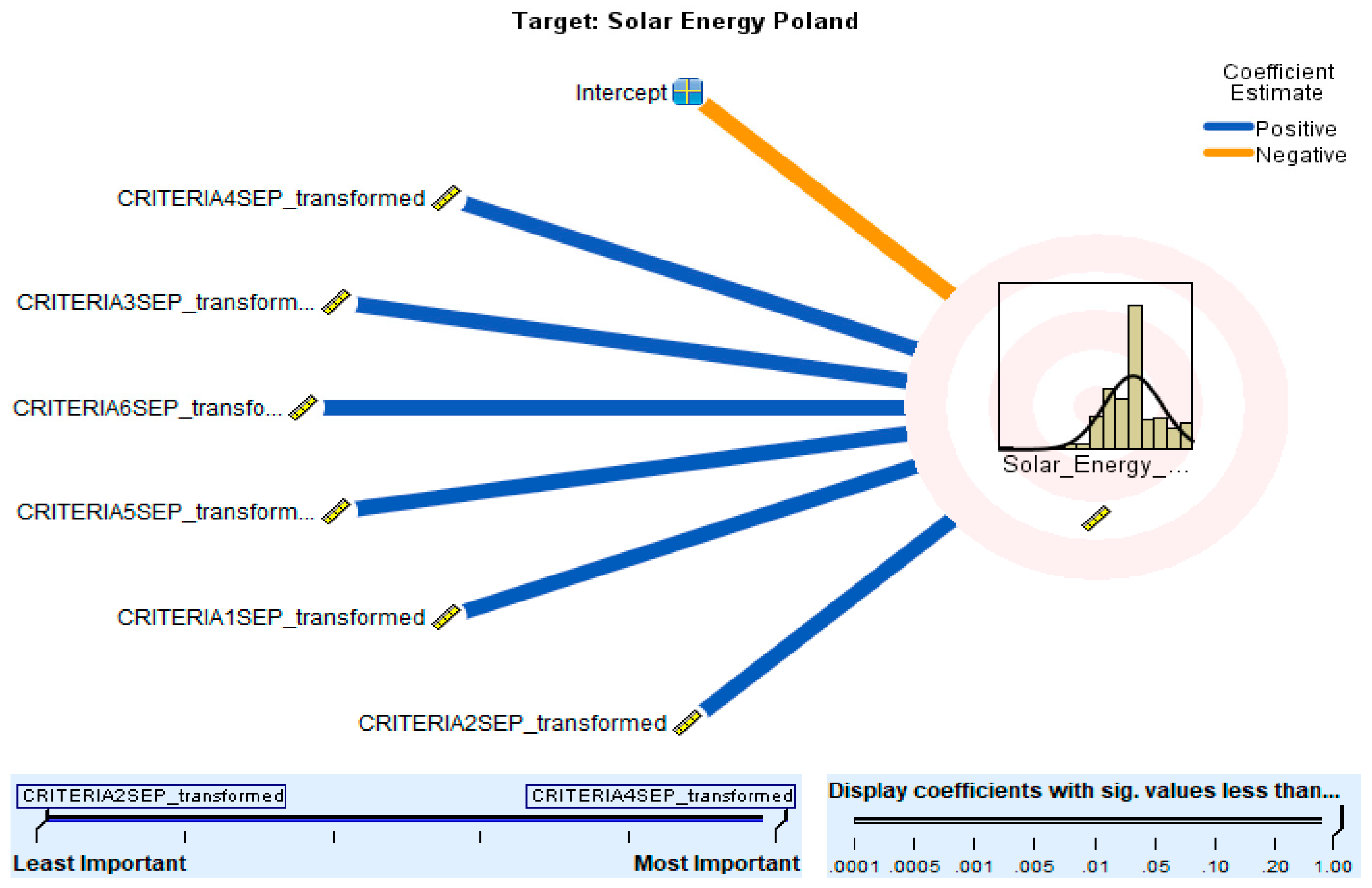

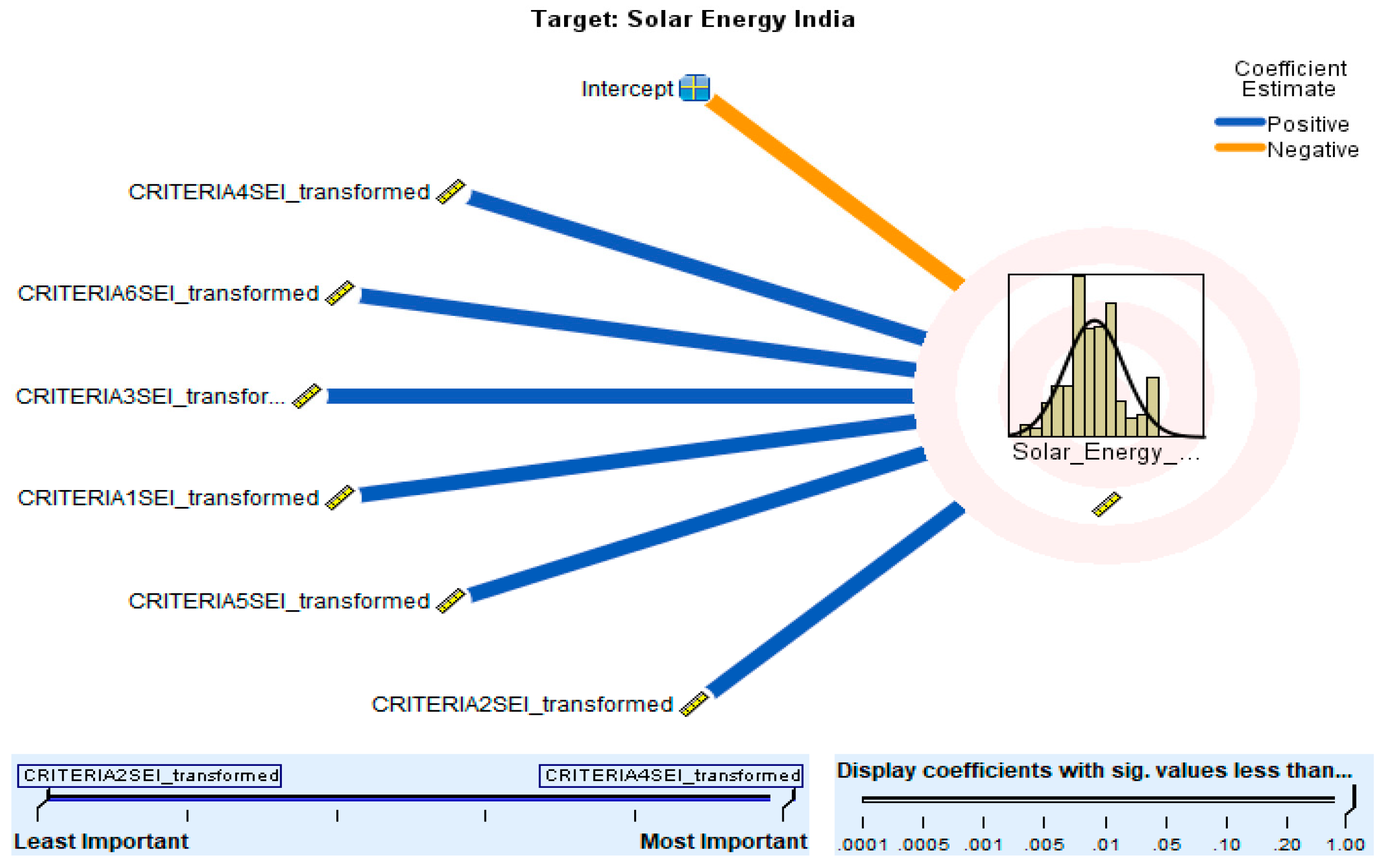

4.1. Solar Energy—Green Consumer Value Criteria Ranking and Comparison

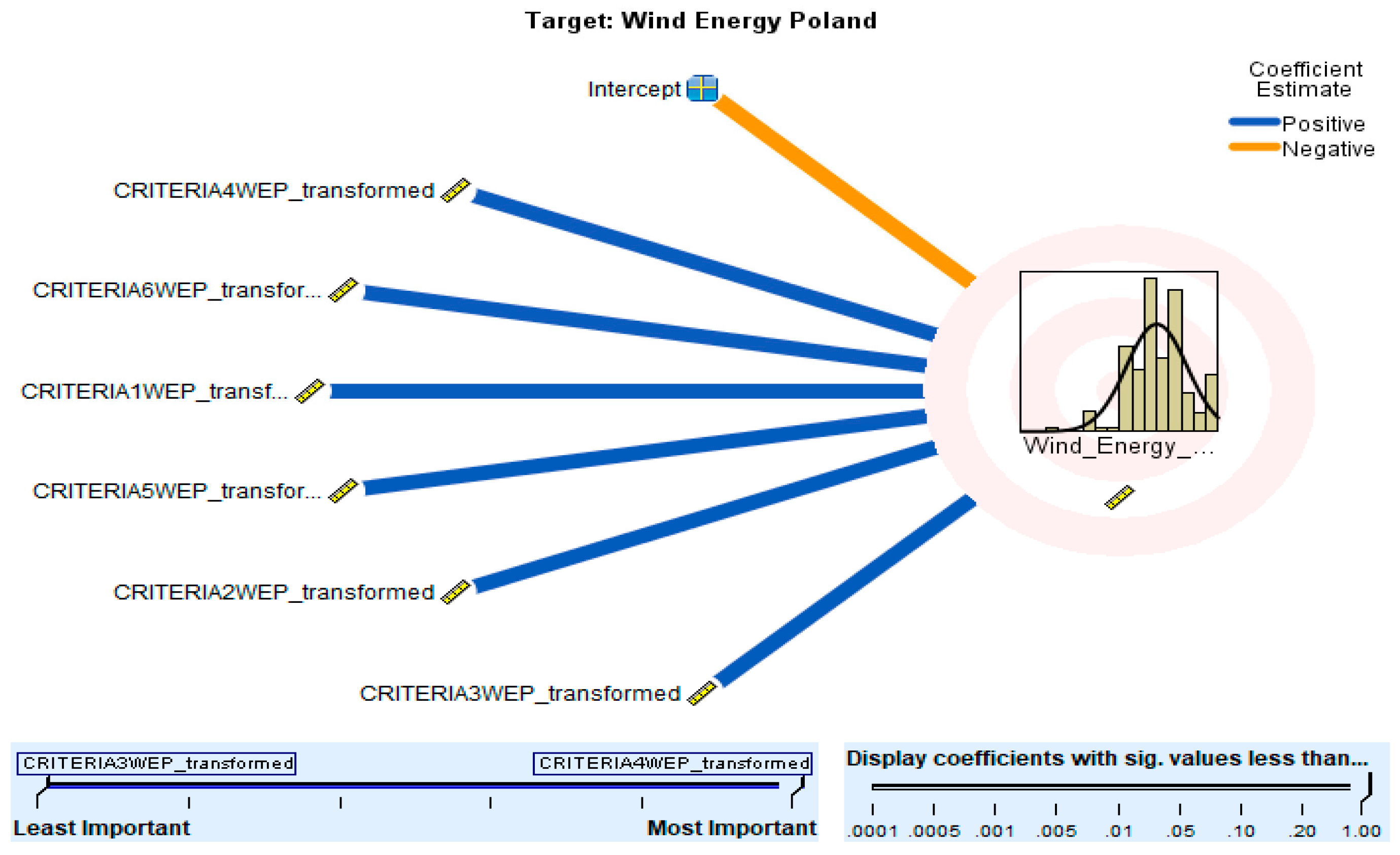

4.2. Wind Energy—Green Consumer Value Criteria Ranking and Comparison

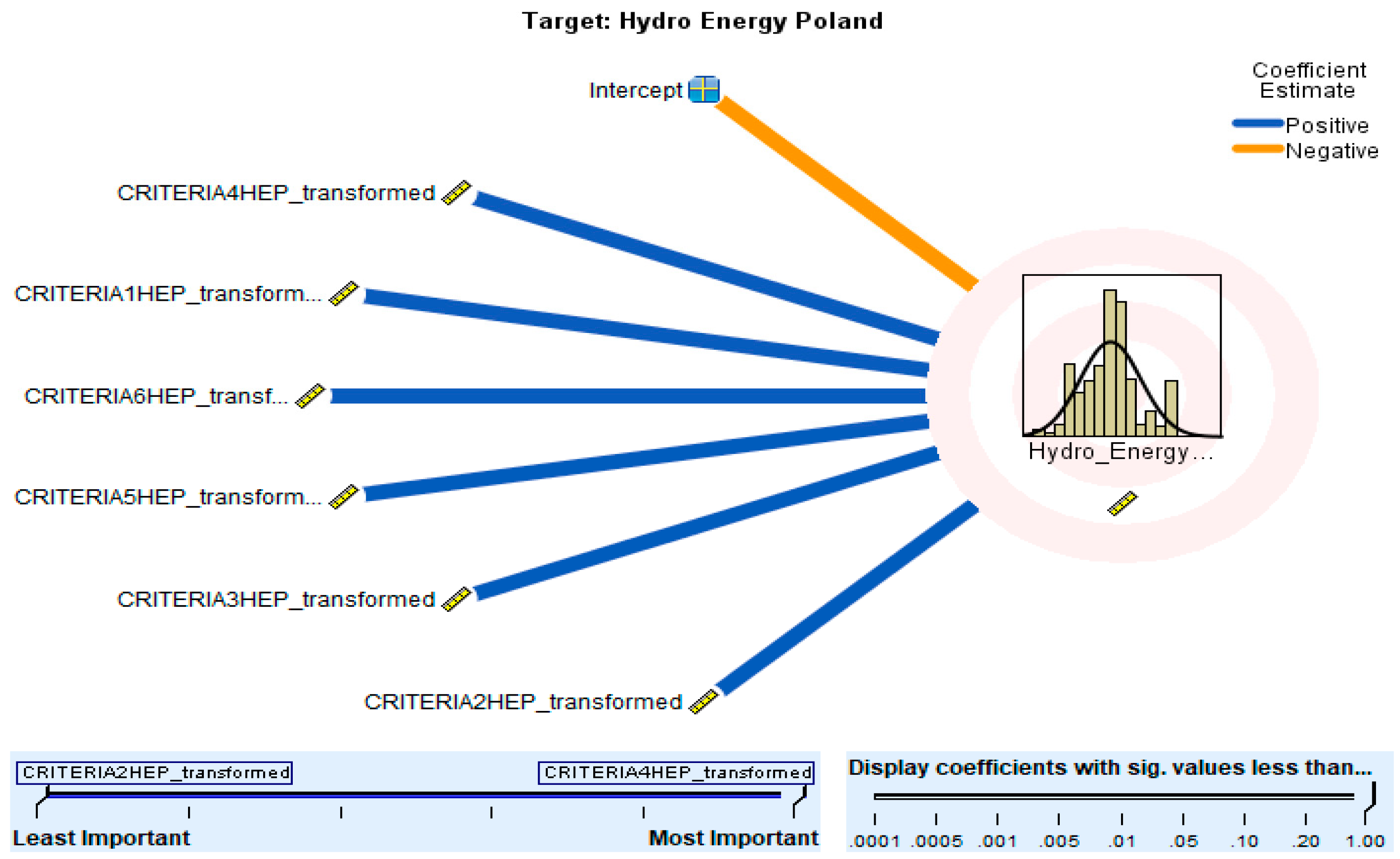

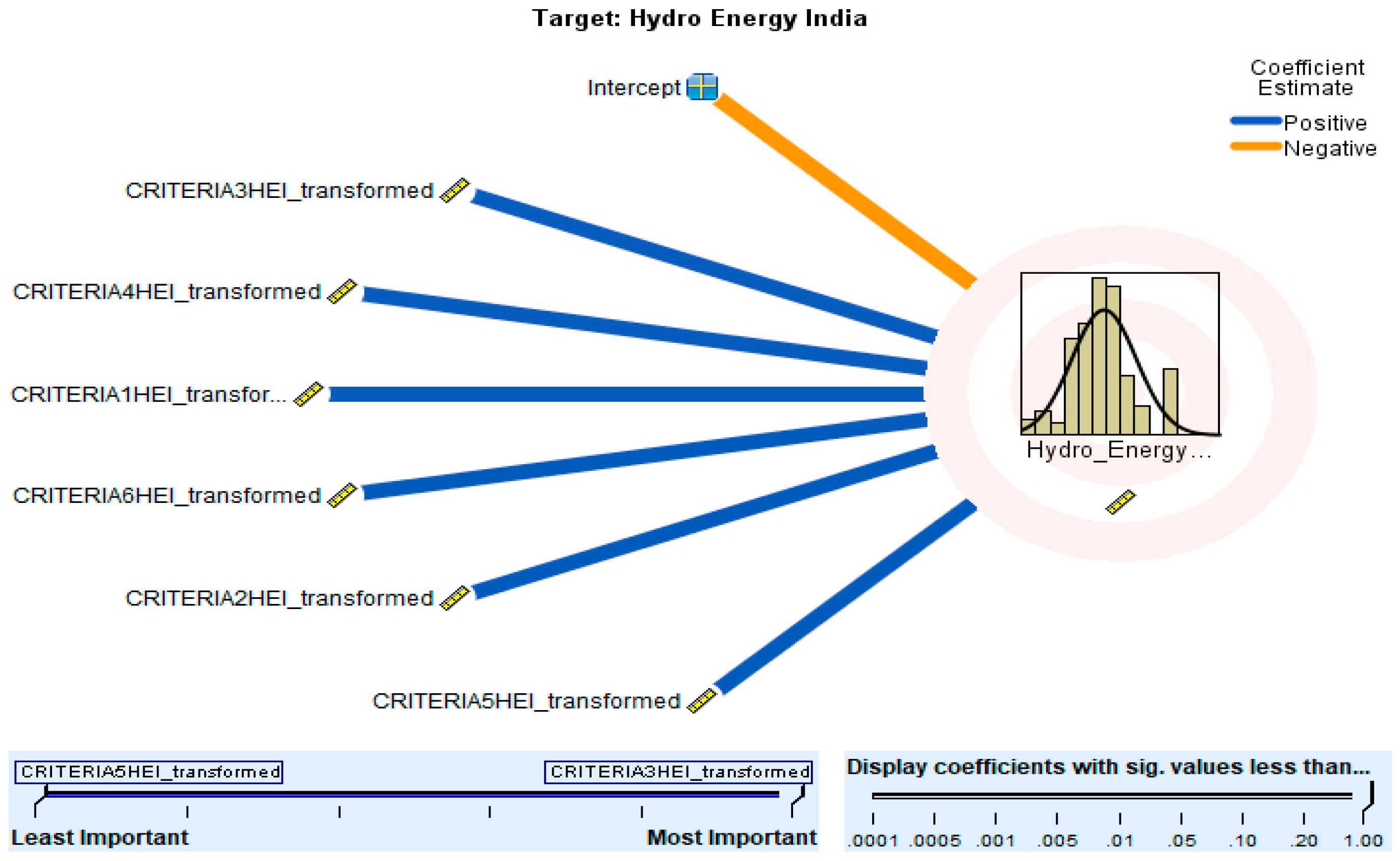

4.3. Hydro Energy—Green Consumer Value Criteria Ranking and Comparison

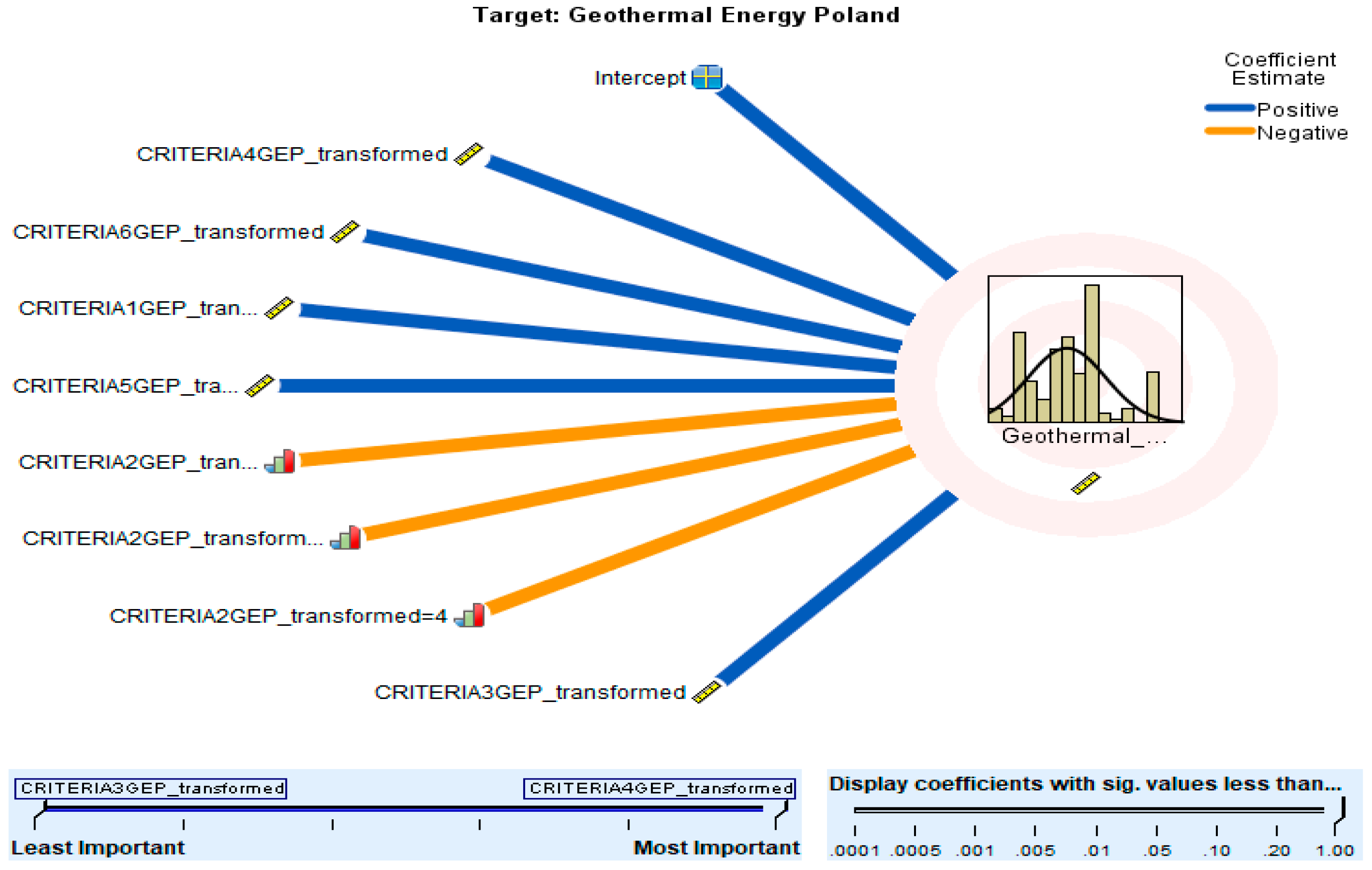

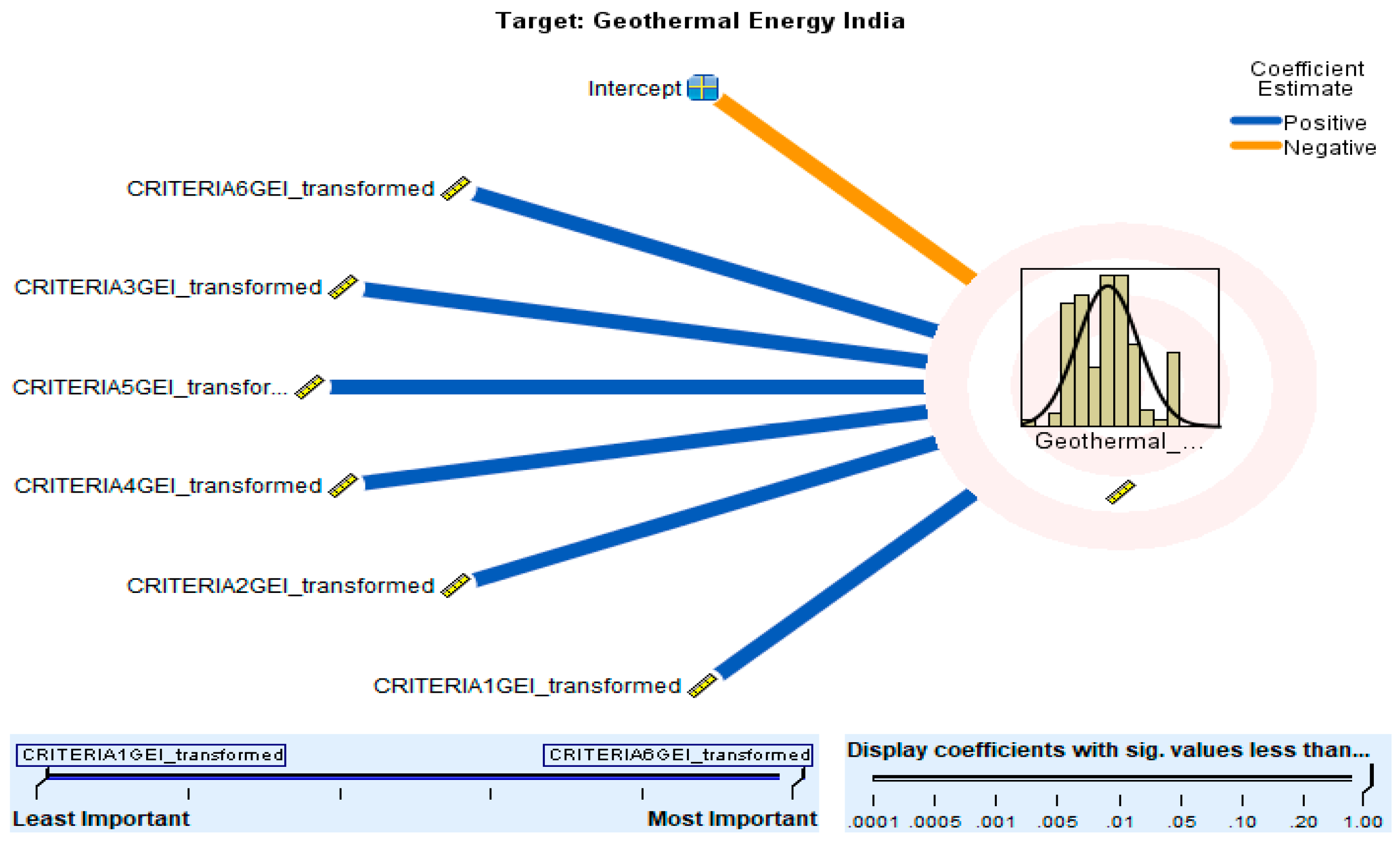

4.4. Geothermal Energy—Green Consumer Value Criteria Ranking and Comparison

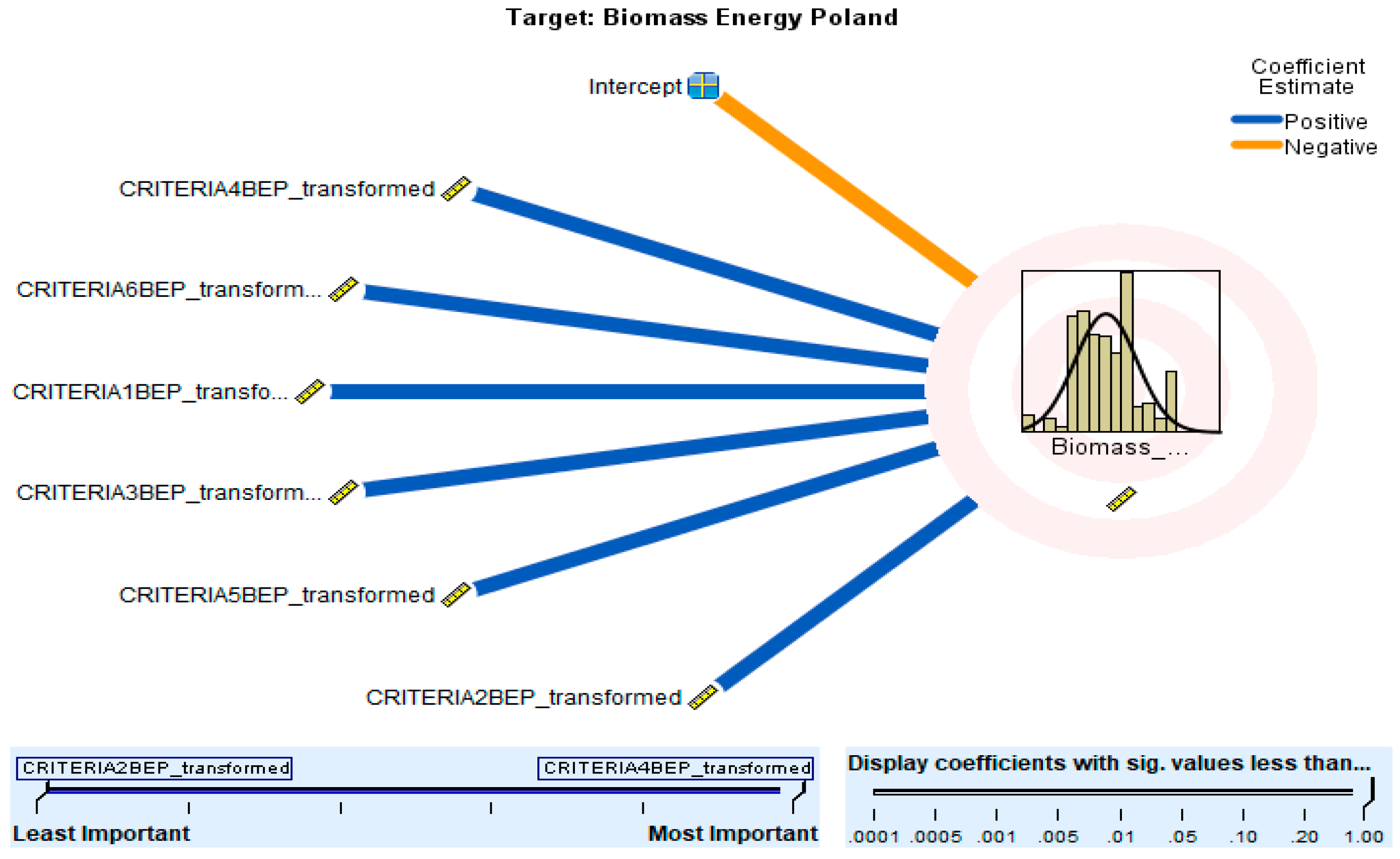

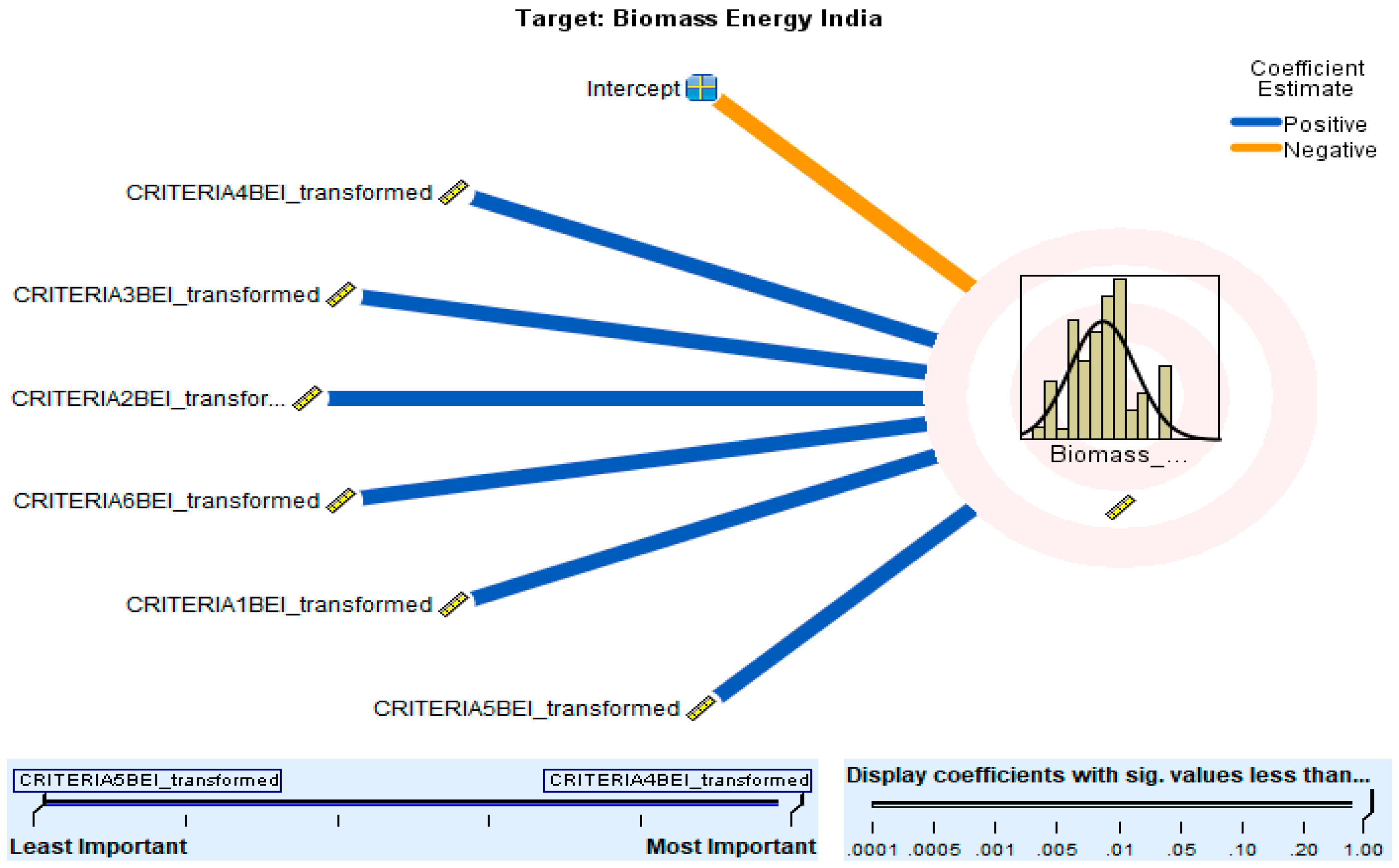

4.5. Biomass Energy—Green Consumer Value Criteria Ranking and Comparison

4.6. Renewable Energy Green Consumer Value Criteria Assessment

5. Conclusions and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Brodny, J.; Tutak, M.; Saki, S.A. Forecasting the Structure of Energy Production from Renewable Energy Sources and Biofuels in Poland. Energies 2020, 13, 2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carballo-Penela, A.; Castromán-Diz, J.L. Environmental Policies for Sustainable Development: An Analysis of the Drivers of Proactive Environmental Strategies in the Service Sector: Environmental Policies for Sustainable Development. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2015, 24, 802–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jałowiec, T.; Wojtaszek, H. Analysis of the RES Potential in Accordance with the Energy Policy of the European Union. Energies 2021, 14, 6030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamkhezri, J.; Thacher, J.A.; Chermak, J.M. Consumer Preferences for Solar Energy: A Choice Experiment Study. Energy J. 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Shaughnessy, E.; Heeter, J.; Shah, C.; Koebrich, S. Corporate Acceleration of the Renewable Energy Transition and Implications for Electric Grids. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2021, 146, 111160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szaruga, E.; Kłos-Adamkiewicz, Z.; Gozdek, A.; Załoga, E. Linkages between Energy Delivery and Economic Growth from the Point of View of Sustainable Development and Seaports. Energies 2021, 14, 4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulovesi, K.; Oberthür, S. Assessing the EU’s 2030 Climate and Energy Policy Framework: Incremental Change toward Radical Transformation? RECIEL 2020, 29, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, J.Y.; Yusliza, M.; Ramayah, T.; Chiappetta Jabbour, C.J.; Sehnem, S.; Mani, V. Pathways towards Sustainability in Manufacturing Organizations: Empirical Evidence on the Role of Green Human Resource Management. Bus. Strat. Environ. 2020, 29, 212–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Take Action for the Sustainable Development Goals—United Nations Sustainable Development. Available online: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable-development-goals/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Owusu, P.A.; Asumadu-Sarkodie, S. A Review of Renewable Energy Sources, Sustainability Issues and Climate Change Mitigation. Cogent Eng. 2016, 3, 1167990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trends|Tracking SDG 7. Available online: https://trackingsdg7.esmap.org/time?c=World+Central_Asia_and_Southern_Asia+Eastern_Asia_and_South-eastern_Asia+Latin_America_and_the_Caribbean+Northern_America_and_Europe+Oceania+Sub-Saharan_Africa+Western_Asia_and_Northern_Africa&p=Renewable_Energy&i=Renewable_Energy_share_in_Total_Final_Energy_Consumption_(%) (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- 2022—World Energy Transitions Outlook: 2022 1.5 °C Pathw.Pdf. Available online: https://www.irena.org/-/media/files/irena/agency/publication/2022/mar/irena_weto_summary_2022.pdf?la=en&hash=1da99d3c3334c84668f5caae029bd9a076c10079 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Keidel, J.; Bican, P.M.; Riar, F.J. Influential Factors of Network Changes: Dynamic Network Ties and Sustainable Startup Embeddedness. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- 2022 Initiative Foundation—Co-Creation & Acceleration to Reach the Sustainable Development Goals. Available online: https://www.2022initiative.org/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- SDG Indicators. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2019/goal-07/ (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Bartoszczuk, P.; Singh, U.S.; Rutkowska, M. An Empirical Analysis of Renewable Energy Contributions Considering GREEN Consumer Values—A Case Study of Poland. Energies 2022, 15, 1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sachdeva, S.; Jordan, J.; Mazar, N. Green Consumerism: Moral Motivations to a Sustainable Future. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2015, 6, 60–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinto, D.C.; Nique, W.M.; Añaña, E.D.S.; Herter, M.M. Green Consumer Values: How Do Personal Values Influence Environmentally Responsible Water Consumption? Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2011, 35, 122–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutkowska, M.; Bartoszczuk, P.; Singh, U.S. Management of GREEN Consumer Values in Renewable Energy Sources and Eco Innovation in INDIA. Energies 2021, 14, 7061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboagye, B.; Gyamfi, S.; Ofosu, E.A.; Djordjevic, S. Status of Renewable Energy Resources for Electricity Supply in Ghana. Sci. Afr. 2021, 11, e00660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haws, K.L.; Winterich, K.P.; Naylor, R.W. Seeing the World through GREEN-Tinted Glasses: Green Consumption Values and Responses to Environmentally Friendly Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2014, 24, 336–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.A.; Mishra, A.; Tiamiyu, M.F. GREEN Consumption Values and Indian Consumers’ Response to Marketing Communications. JCM 2016, 33, 562–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Dong, F. Why Do Consumers Make Green Purchase Decisions? Insights from a Systematic Review. IJERPH 2020, 17, 6607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.-C.; Wang, H.-M.; Huang, H.-L.; Ho, C.-W. Consumer Attitude and Purchase Intention toward Rooftop Photovoltaic Installation: The Roles of Personal Trait, Psychological Benefit, and Government Incentives. Energy Environ. 2020, 31, 21–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ancygier, A. Poland and the European Climate Policy: An Uneasy Relationship. Kwart. Nauk. OAP UW E-Polit. 2013, 7, 76–93. [Google Scholar]

- Tolba, M.K. The Premises for Building a Sustainable Society—Address to the World Commission on Environment and Development; United Nations Environment Programme: Nairobi, Kenya, 1984; Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/5987our-common-future.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Pezzey, J.C.V. Economic Analysis of Sustainable Growth and Sustainable Development; Environment Department Working Paper No. 15. Published as Sustainable Development Concepts: An Economic Analysis, World Bank Environment Paper No. 2; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan Srivastava, A.; Khan, M.; Khan, F.Y.; Bajpai, S. Role of Renewable Energy in Indian Economy. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2018, 404, 012046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Millard, F. Environmental Policy in Poland. Environ. Politics 1998, 7, 145–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.local2030.org/library/421/Recommendations-to-integrate-the-SDGs-into-local-party-manifestos.pdf (accessed on 13 June 2022).

- Skjærseth, J.B. Implementing EU Climate and Energy Policies in Poland: Policy Feedback and Reform. Environ. Politics 2018, 27, 498–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Policy—An Overview|ScienceDirect Topics. Available online: https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/social-sciences/environmental-policy (accessed on 23 March 2022).

- Singh, U. Total Productive Maintenance a Tool for Efficient Production Management. 2015. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328841028_TOTAL_PRODUCTIVE_MAINTENANCE_A_TOOL_FOR_EFFICIENT_PRODUCTION_MANAGEMENT (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Singh, U.S. Cost Estimation Using Econometric Model for Restaurant Business. QME 2019, 20, 209–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://www.scribd.com/document/371685743/TZW-Sustainability-and-the-Waste-Hierarchy-2003 (accessed on 30 May 2022).

- Singh, U.S. A Conceptual Approach Correlating Behavioral Neuroscience with Vertically Coordinated Vegetable Supply Chain. Sch. J. Arts Humanit. Soc. Sci. 2018, 6, 1021–1027. [Google Scholar]

- Szulecki, K.; Fischer, S.; Gullberg, A.T.; Sartor, O. Shaping the ‘Energy Union’: Between National Positions and Governance Innovation in EU Energy and Climate Policy. Clim. Policy 2016, 16, 548–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kryk, B.; Guzowska, M.K. Implementation of Climate/Energy Targets of the Europe 2020 Strategy by the EU Member States. Energies 2021, 14, 2711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballal, A.; Tambe, S.; Joe, E.T. The Evolution of India’s Environmental Policy. Indian For. 2021, 147, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mensah, J.; Enu-Kwesi, F. Implications of Environmental Sanitation Management for Sustainable Livelihoods in the Catchment Area of Benya Lagoon in Ghana. J. Integr. Environ. Sci. 2019, 16, 23–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Raport U Thanta—Encyklopedia PWN—źródło wiarygodnej i rzetelnej wiedzy. Available online: https://encyklopedia.pwn.pl/haslo/Raport-U-Thanta;3966094.html (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Scopelliti, M.; Molinario, E.; Bonaiuto, F.; Bonnes, M.; Cicero, L.; De Dominicis, S.; Fornara, F.; Admiraal, J.; Beringer, A.; Dedeurwaerdere, T.; et al. What Makes You a ‘Hero’ for Nature? Socio-Psychological Profiling of Leaders Committed to Nature and Biodiversity Protection across Seven EU Countries. J. Environ. Plan. Manag. 2018, 61, 970–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Elliott, J.A. An Introduction to Sustainable Development, 4th ed.; Routledge Perspectives on Development; Routledge: London, UK; Taylor & Francis Group: New York, NY, USA, 2013; ISBN 978-0-415-59072-3. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, E.; Milner-Gulland, E.J.; Knight, A.T.; Ling, M.A.; Darrah, S.; Soesbergen, A.; Burgess, N.D. Status and Trends in Global Ecosystem Services and Natural Capital: Assessing Progress Toward Aichi Biodiversity Target 14. Conserv. Lett. 2016, 9, 429–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montaldo, C.R.B. Sustainable Development Approaches for Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation & Community Capacity Building for Rural Development and Poverty Alleviation. 17. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/877LR%20Sustainable%20Development%20v2.pdf (accessed on 21 April 2022).

- Lélé, S.M. Sustainable Development: A Critical Review. World Dev. 1991, 19, 607–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahzalal, M.; Hassan, A. Communicating Sustainability: Using Community Media to Influence Rural People’s Intention to Adopt Sustainable Behaviour. Sustainability 2019, 11, 812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime World Drug Report 2016; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2016; ISBN 978-92-1-148286-7. [Google Scholar]

- Kasztelan, A. Green Growth, Green Economy and Sustainable Development: Terminological and Relational Discourse. Prague Econ. Pap. 2017, 26, 487–499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Proczek, R. Pojęcie zrównoważonego rozwoju. Available online: http://urbnews.pl/pojecie-zrownowazonego-rozwoju/ (accessed on 24 March 2022).

- Deliana, Y.; Rum, I.A. How Does Perception on Green Environment across Generations Affect Consumer Behaviour? A Neural Network Process. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2019, 43, 358–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Testa, F.; Pretner, G.; Iovino, R.; Bianchi, G.; Tessitore, S.; Iraldo, F. Drivers to Green Consumption: A Systematic Review. Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2021, 23, 4826–4880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gleim, M.J.; Lawson, S. Spanning the Gap: An Examination of the Factors Leading to the Green Gap. J. Consum. Mark. 2014, 31, 503–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Z.-H.; Chang, C.-T.; Lee, Y.-K. Linking Hedonic and Utilitarian Shopping Values to Consumer Skepticism and Green Consumption: The Roles of Environmental Involvement and Locus of Control. Rev. Manag. Sci. 2020, 14, 61–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://assets.ey.com/content/dam/ey-sites/ey-com/en_gl/topics/power-and-utilities/ey-recai-59-top-40-ranking-may-2022.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2022).

- Cohen, J. A Power Primer. Psychol. Bull. 1992, 112, 155–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 1992, 1, 98–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: A Flexible Statistical Power Analysis Program for the Social, Behavioral, and Biomedical Sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, U.; Mishra, U. Assessment of Need for Vertical Coordination in Supply Chain of Vegetable Industry. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 22, 1417–1423. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, U.S.; Bradosti, H. Acceptability of Banking Operations in Iraqi Kurdistan. Res. J. Financ. Account. 2015, 6, 276–286. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarski, M.; Singh, U.S.; Nermend, K. Application of EEG Metrics in the Decision-Making Process. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Methods in Experimental Economics, Warsaw, Poland, 28–29 November 2018; pp. 187–199. [Google Scholar]

- Piwowarski, M.; Miłaszewicz, D.; Łatuszyńska, M.; Borawski, M.; Nermend, K. Application of the Vector Measure Construction Method and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity Ideal Solution for the Analysis of the Dynamics of Changes in the Poverty Levels in the European Union Countries. Sustainability 2018, 10, 2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Piwowarski, M.; Borawski, M.; Nermend, K. The Problem of Non-Typical Objects in the Multidimensional Comparative Analysis of the Level of Renewable Energy Development. Energies 2021, 14, 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nermend, K.; Łatuszyńska, M. (Eds.) Experimental and Quantitative Methods in Contemporary Economics: Computational Methods in Experimental Economics (CMEE) 2018 Conference; Springer Proceedings in Business and Economics; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-030-30250-4. [Google Scholar]

- Europe Sustainable Development Report 2021. Available online: https://eu-dashboards.sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Sustainable Development Report 2022. Available online: https://dashboards.sdgindex.org/ (accessed on 19 June 2022).

- Singh, S.; Singh, G.A. Assessing the Impact of the Digital Divide on Indian Society: A Study of Social Exclusion. Res. Soc. Chang. 2021, 13, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, G.A.; Kaur, R. Relationship between Propensity to Social Innovation and Striving for Gender Equality: Sample Study Based on the Example of India. Główny Urząd Stat. 2022, 67, 41–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, S.; Singh, U.S. A Study Assessing the Brand Loyalty Creation by Promotion Mix for KOTON Brand. JXU 2020, 14, 3460–3480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsakaa, A.A.; Borawska, A.; Borawski, M.; Łatuszyńska, M.; Piwowarski, M.; Babiloni, F.; Nermend, K. Cognitive Neuroscience Techniques in Determining the Right Time of Advertising. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 671, 012033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarski, M.; Miłaszewicz, D.; Łatuszyńska, M.; Nermend, K. Multi-Criteria Assessment of the Company’s Location Selection: A Dynamic Approach. ERSJ 2019, XXII, 215–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nermend, K.; Piwowarski, M.; Borawski, M. Decision Making Methods in Comparative Studies of Complex Economic Processes Management. EIJS 2020, 61, 652–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mateusz, P.; Danuta, M.; Małgorzata, Ł.; Mariusz, B.; Kesra, N. TOPSIS and VIKOR Methods in Study of Sustainable Development in the EU Countries. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2018, 126, 1683–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piwowarski, M.; Singh, U.S.; Nermend, K. The Cognitive Neuroscience Methods in the Analysis of the Impact of Advertisements in Shaping People’s Health Habits. Eur. Res. Stud. J. 2019, XXI, 457–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Rank | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 44 | Thailand | 74.13 |

| 55 | Vietnam | 72.76 |

| 56 | China | 72.38 |

| 60 | Singapore | 71.72 |

| 67 | Maldives | 71.03 |

| 70 | Bhutan | 70.49 |

| 72 | Malaysia | 70.38 |

| 76 | SriLanka | 70.03 |

| 82 | Indonesia | 69.16 |

| 93 | BruneiDarussalam | 67.10 |

| 95 | Philippines | 66.64 |

| 98 | Nepal | 66.18 |

| 103 | Myanmar | 64.27 |

| 104 | Bangladesh | 64.22 |

| 107 | Cambodia | 63.75 |

| 109 | Mongolia | 63.51 |

| 111 | LaoPDR | 63.39 |

| 121 | India | 60.32 |

| 125 | Pakistan | 59.34 |

| Rank | Country | Score |

|---|---|---|

| 8 | Pakistan | 99.42 |

| 13 | India | 99.29 |

| 19 | Myanmar | 99.18 |

| 33 | Nepal | 98.55 |

| 38 | Bangladesh | 97.91 |

| 47 | Cambodia | 97.56 |

| 48 | Indonesia | 97.56 |

| 55 | Philippines | 97.21 |

| 73 | Vietnam | 95.31 |

| 76 | China | 94.85 |

| 77 | Maldives | 94.80 |

| 81 | Mongolia | 94.02 |

| 86 | Sri Lanka | 93.65 |

| 89 | Bhutan | 93.36 |

| 101 | Lao PDR | 90.19 |

| 108 | Thailand | 86.71 |

| 118 | Malaysia | 79.19 |

| 133 | Brunei Darussalam | 67.3 |

| 163 | Singapore | 33.03 |

| Renewable Energy Sources | Poland | India | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria | Importance | Criteria | Importance | |

| Solar Energy | CRITERIA 4 | 0.278 | CRITERIA 4 | 0.228 |

| CRITERIA 3 | 0.185 | CRITERIA 6 | 0.207 | |

| CRITERIA 6 | 0.159 | CRITERIA 3 | 0.192 | |

| CRITERIA 5 | 0.152 | CRITERIA 1 | 0.154 | |

| CRITERIA 1 | 0.119 | CRITERIA 5 | 0.117 | |

| CRITERIA 2 | 0.108 | CRITERIA 2 | 0.101 | |

| Wind Energy | CRITERIA 4 | 0.327 | CRITERIA 4 | 0.207 |

| CRITERIA 6 | 0.174 | CRITERIA 3 | 0.198 | |

| CRITERIA 1 | 0.145 | CRITERIA 1 | 0.158 | |

| CRITERIA 5 | 0.144 | CRITERIA 2 | 0.155 | |

| CRITERIA 2 | 0.110 | CRITERIA 6 | 0.142 | |

| CRITERIA 3 | 0.100 | CRITERIA 5 | 0.141 | |

| Hydro Energy | CRITERIA 4 | 0.257 | CRITERIA 3 | 0.249 |

| CRITERIA 1 | 0.192 | CRITERIA 4 | 0.224 | |

| CRITERIA 6 | 0.168 | CRITERIA 1 | 0.157 | |

| CRITERIA 5 | 0.152 | CRITERIA 6 | 0.149 | |

| CRITERIA 3 | 0.116 | CRITERIA 2 | 0.121 | |

| CRITERIA 2 | 0.116 | CRITERIA 5 | 0.099 | |

| Geothermal Energy | CRITERIA 4 | 0.273 | CRITERIA 6 | 0.261 |

| CRITERIA 6 | 0.203 | CRITERIA 3 | 0.180 | |

| CRITERIA 1 | 0.173 | CRITERIA 5 | 0.155 | |

| CRITERIA 5 | 0.136 | CRITERIA 4 | 0.153 | |

| CRITERIA 2 | 0.110 | CRITERIA 2 | 0.142 | |

| CRITERIA 3 | 0.106 | CRITERIA 1 | 0.108 | |

| Biomass Energy | CRITERIA 4 | 0.233 | CRITERIA 4 | 0.209 |

| CRITERIA 6 | 0.223 | CRITERIA 3 | 0.207 | |

| CRITERIA 1 | 0.174 | CRITERIA 2 | 0.172 | |

| CRITERIA 3 | 0.150 | CRITERIA 6 | 0.155 | |

| CRITERIA 5 | 0.125 | CRITERIA 1 | 0.134 | |

| CRITERIA 2 | 0.095 | CRITERIA 5 | 0.124 | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Singh, U.S.; Rutkowska, M.; Bartoszczuk, P. Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values Comparing Poland and India Aligned with Environment Policy for Sustainable Development. Energies 2022, 15, 5046. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15145046

Singh US, Rutkowska M, Bartoszczuk P. Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values Comparing Poland and India Aligned with Environment Policy for Sustainable Development. Energies. 2022; 15(14):5046. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15145046

Chicago/Turabian StyleSingh, Uma Shankar, Małgorzata Rutkowska, and Paweł Bartoszczuk. 2022. "Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values Comparing Poland and India Aligned with Environment Policy for Sustainable Development" Energies 15, no. 14: 5046. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15145046

APA StyleSingh, U. S., Rutkowska, M., & Bartoszczuk, P. (2022). Renewable Energy Decision Criteria on Green Consumer Values Comparing Poland and India Aligned with Environment Policy for Sustainable Development. Energies, 15(14), 5046. https://doi.org/10.3390/en15145046