Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools

Abstract

1. Introduction

- -

- In Germany, the total number of indoor and outdoor swimming pools is 6006; currently 31 pools are under construction (available on 18 February 2021), outdoor and indoor swimming pools comprise 53% and 47%, respectively [11].

- -

- In Switzerland, most of today’s swimming pools which are mainly classical public indoor pools that were built in 1970s without fun and entertainment attractions or teaching pools; most of them need major and fundamental renovation. Currently there are approx. 470 public indoor pools and about 350 school pools, as well as an additional 1000 pools in hotels, hospitals, etc. There are currently around 600 outdoor swimming pools and have similar case [12,13].

- -

- In the UK, the number of swimming pool facilities is 3170, but the total number of the pools is 4559 [14].

- -

- -

- According to the State Health Institute database, there were 957 public swimming pools in Czech Republic in 2014 [17].

- -

- Spain has a large number of public and communal swimming pools: the total swimming pools are of 121,070 facilities, according to data of Piscina & Wellness Barcelona Show and the Spanish Association of Swimming Pool Sector Professionals (ASOFAP) [18]. Additionally, there are plans to enhance this number by 26,000 new swimming pools in the near future [19].

2. Water Use in Swimming Pools

- Initial filling water;

- Makeup water for maintaining the water level within an operating range;

- Backwash water for cleaning water filters; and

- Cleaning water for pool decks and structures.

- Size of the pool (surface area and depth);

- Local climate: Precipitation, evaporation (air and water temperatures, wind, humidity, shadowiness, etc.);

- Design conditions of the pool: Presence and use of a pool cover, pool water temperature, presence of water aesthetic features like a fountain or waterfall, PH and chemical content of pool water, leakage;

- Individual maintenance trends: Frequency of backwashing, frequency and the method of pool and pool deck cleaning;

- Human behaviour: Splashing-out and swimming habits.

2.1. Pool Water Temperature Requirements

- (A)

- Poland [24]:

- -

- Water temperature in swimming pools for swimming lessons and jumping pools: 27 °C to 28 °C;

- -

- Water temperature in children’s swimming pools: 30 °C to 32 °C;

- -

- Temperature in swimming pools of therapeutic type: 32 °C to 36 °C.

- (B)

- International Swimming Federation FINA specified the regulations which are required for swimming pool water temperatures according to the intended use [7]:

- -

- In swimming pools, also for Olympic games and world championships: 25° to 28 °C;

- -

- Diving facilities, also for Olympic games and world championships: min. 26 °C;

- -

- Water polo, as well as for Olympic games and world championships: min. 26 ± 1 °C;

- -

- Artistic swimming, likewise, for Olympic games and world championships: min. 27 ± 1 °C;

- -

- High diving: min. 18 °C in open water venues and preferable min. 26 °C in venues with an artificial pools.

- (C)

- The Swiss Swimming Federation SSCHV [25] and the Swiss Ministry of Sport BASPO [6] adopt the guidelines of the FINA, which sets out the requirements for swimming facilities, water jumping, water ball and synchronous swimming and complements them with recommendations, in particular for systems intended for use by the general public. FINA’s rules are reviewed every four years [25].

- -

- Sports swimming pool: 25 to 28 °C, but SSCHV recommends min. 26 °C for indoor and 23 °C recommended for outdoor pool;

- -

- Swimming pool for Olympic games and world championships: min. 24 °C, preferably 25 °C to 26 °C;

- -

- Water polo games should be played at water temperatures below 20 °C only with the consent of both teams (in Switzerland, water polo games can be played at water temperatures below 20 °C only with the consent of both teams);

- -

- Artistic swimming, also for Olympic games and world championships: min. 26 ± 1 °C;

- -

- Non-swimming and recreational swimming pools: 28 to 30 °C;

- -

- Swimming pool for small children (paddling pools), play area for children in water: 30 to 32 °C (in the outdoor pool: 23 to 26 °C);

- -

- Aqua-baby pool (6 month to 3 years): 30 to 34 °C;

- -

- Swimming pools for small children who swim with their parents (deep): 32 to 34 °C;

- -

- Play pools: around 30 °C;

- -

- Getting used to the water in the paddling pool and toddler water play pools: 30 to 32 °C (in the outdoor pool 23 to 26 °C);

- -

- Warm outdoor pool with a bathing area in the bathing hall and with benches, massage jets, flow zones and often other attractions: 32 to 34 °C;

- -

- Hot whirlpools: approx. 37 °C;

- -

- Therapeutic gymnastics and physiotherapy: 32 to 34 °C;

- -

- Aqua aerobics, aqua fitness: 27 to 30 °C;

- -

- Aqua jogging: 27 to 28 °C (in the outdoor pool: 23 to 24 °C);

- -

- Swimming pools for swimming lessons: approx. 30 °C (in the outdoor pool: 23 to 26 °C).

- (D)

- The German Swimming Association (DSV) [26,27,28,29,30,31,32] defines the water temperature in competitions as 25 to 28 °C, but:

- -

- Temperatures in pools for water polo: min. 21 °C;

- -

- Pools for artistic swimming up to min. 26 ± 1 °C;

- -

- Pools for diving: min. 26 ± 1 °C;

- -

- Pools for open water swimming: min. 16 °C and max. 31 °C;

- -

- Masters competitions in open water swimming may not be held at water temperatures below 18 °C.

- -

- -

- Category B for high requirements: national, official competitions of the DSV and its regional associations;

- -

- Category C for medium requirements: further official competitions of the DSV and its regional associations;

- -

- Category D for sub-requirements: regional, official competitions, leisure and popular sports.

2.2. Indoor Thermal Requirements and Comfort Design Conditions in Indoor Swimming Pools

2.3. Total Water Consumption in Indoor Swimming Pools

2.3.1. Total Water Consumption—European Guidelines

2.3.2. Total Water Consumption in Swimming Pools—Polish Database

- -

- The first one treats water for a 25 m × 12.5 m swimming pool;

- -

- The second is for a recreational pool with hydro massage and a slide.

2.4. Grey Water

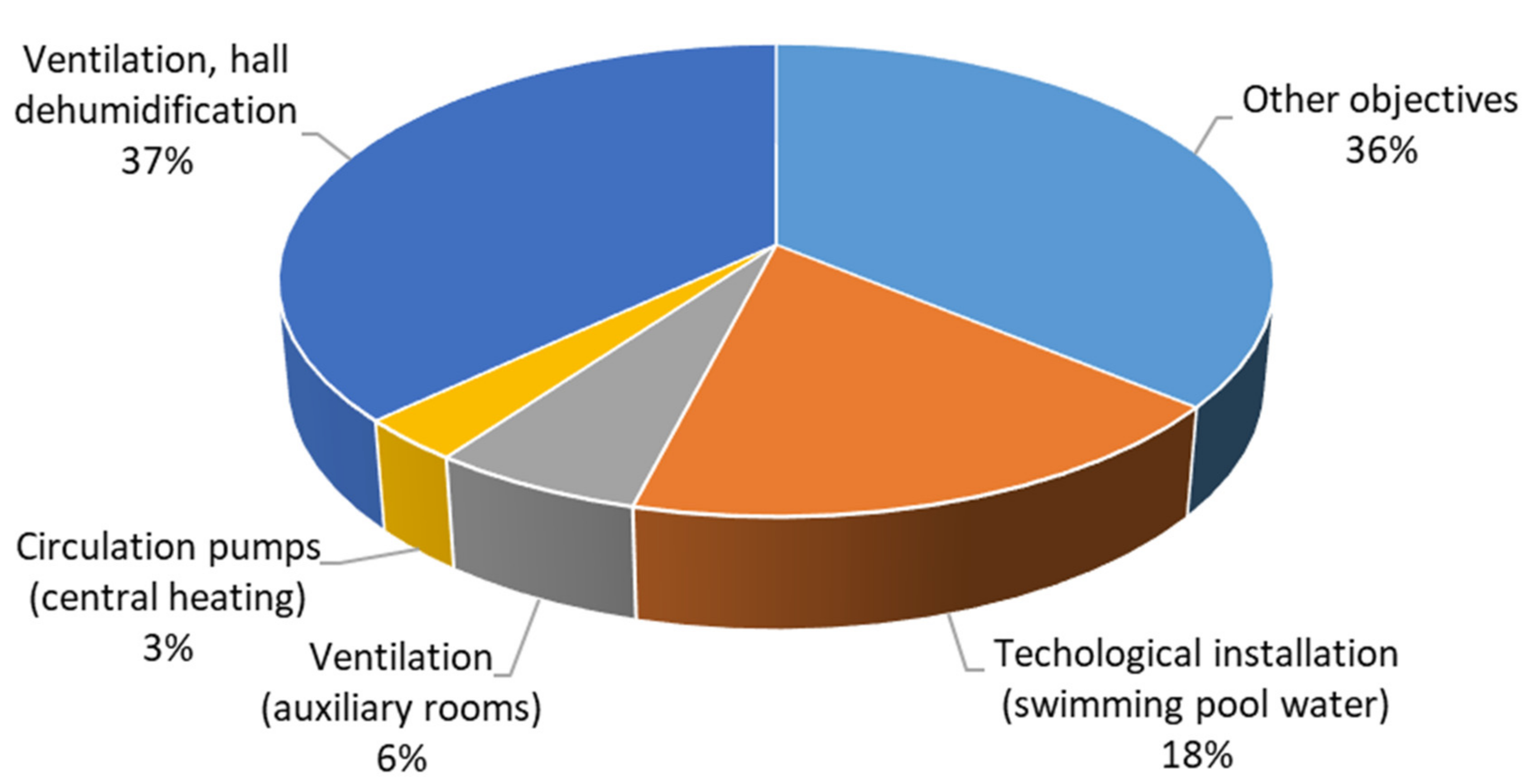

3. Energy Consumption in Swimming Pools

- Pool surface area;

- Water depth;

- Target water temperature;

- Availability of a pool cover;

- Ambient air temperature, wind speed, etc.;

- Colour of the pool;

- Meteorological conditions of the area where the pool is located.

- Pool surface area;

- Water depth;

- Target water temperature.

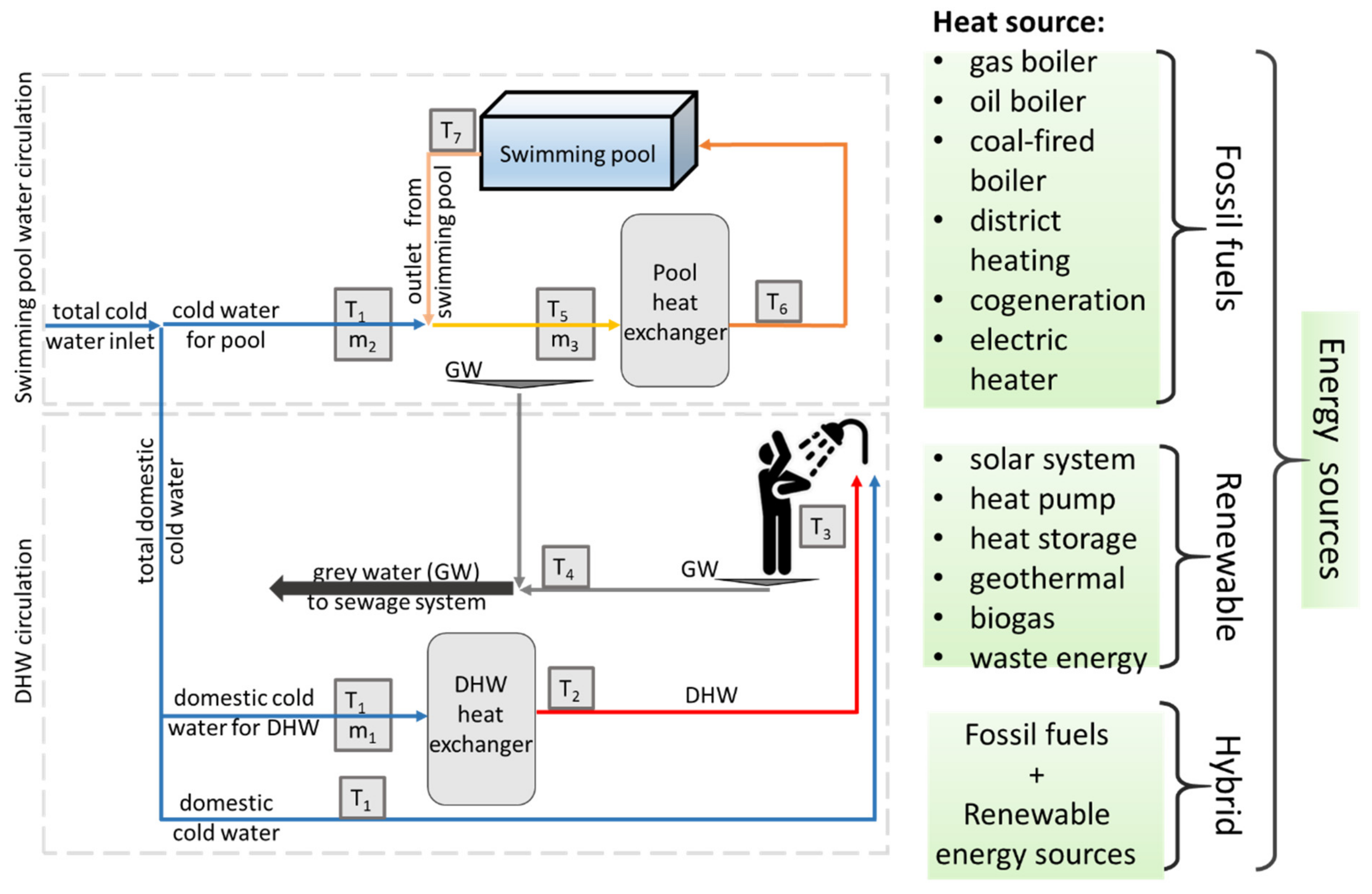

3.1. Energy Sources for Swimming Pool Water Heating

3.2. Conventional Energy Sources

3.3. Renewable Energy Sources

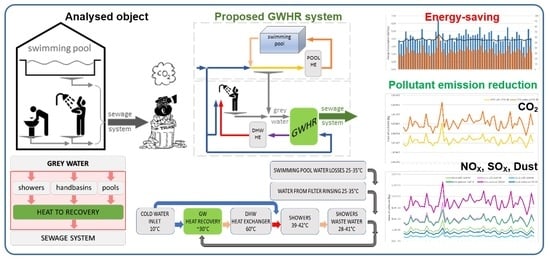

3.4. GWHR Systems in Indoor Swimming Pools

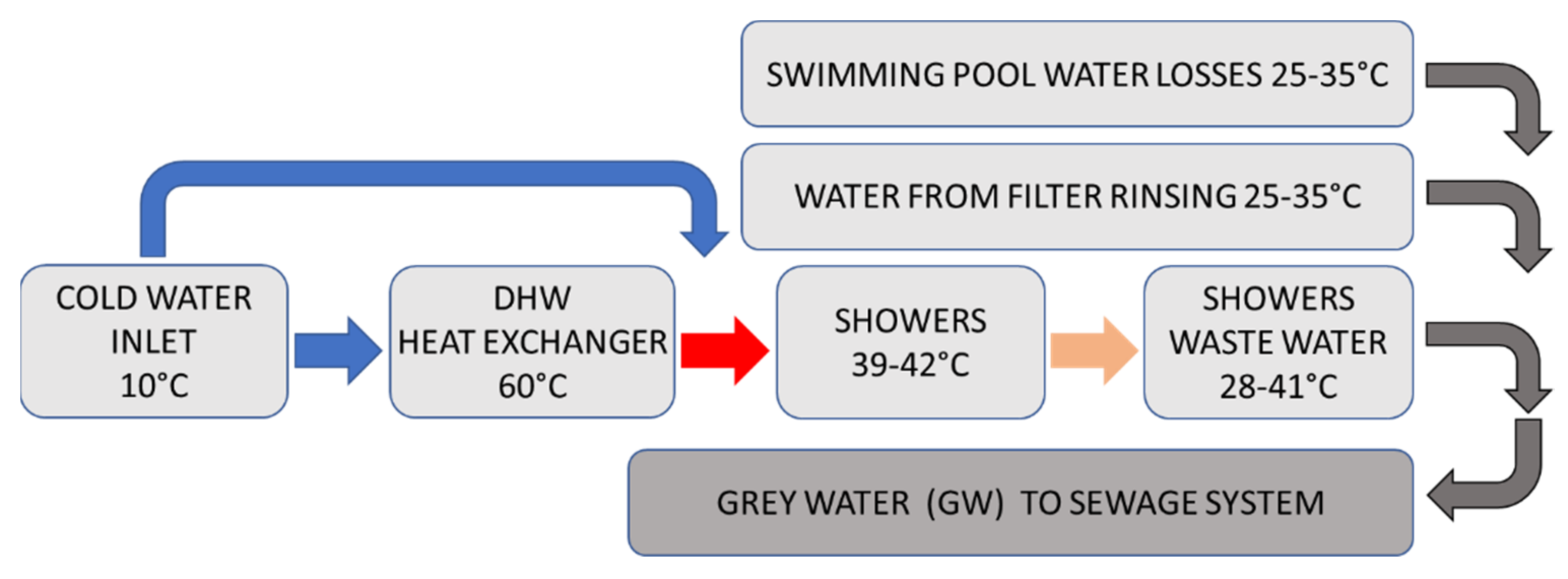

- Heat recovery from water discharged into the pool’s drainage system: this type of heat recovery practically takes place without an auxiliary source of energy, it is the most economical form of energy saving in an indoor pool and should therefore not be missing in any pool installation.

- Heat recovery from rinsing water for filters: this type requires, in addition to a heat exchanger, a tank for storing the cooled filter rinsing water. If there is an available space for storage, it can be integrated into the system; there is also an economic option to save energy.

- Heat recovery from wastewater: it concerns heat recovery from discharged sewage in sanitary facilities (showers and handbasins) at the swimming pool. Heat exchangers and heat pumps can be used in this case.

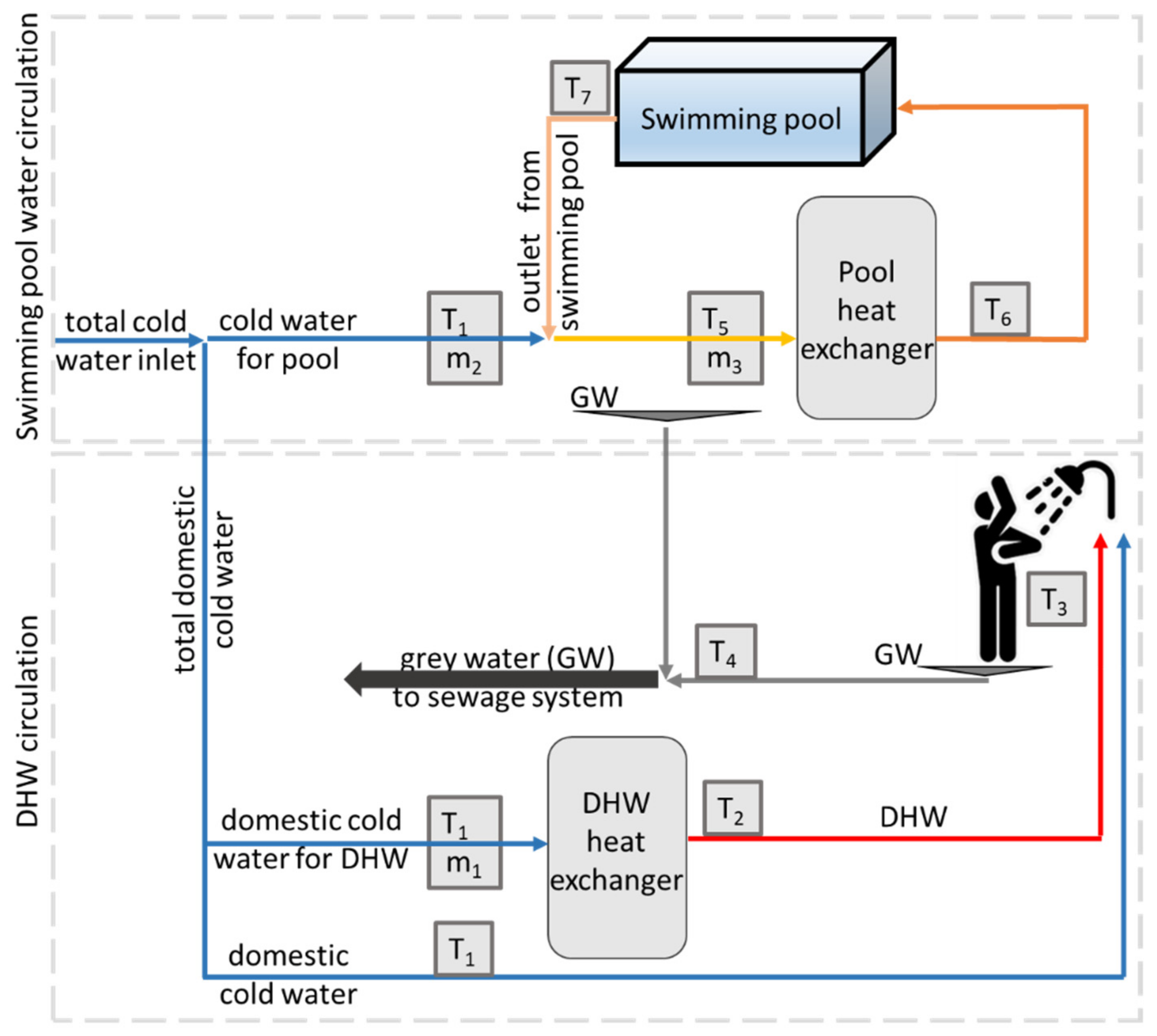

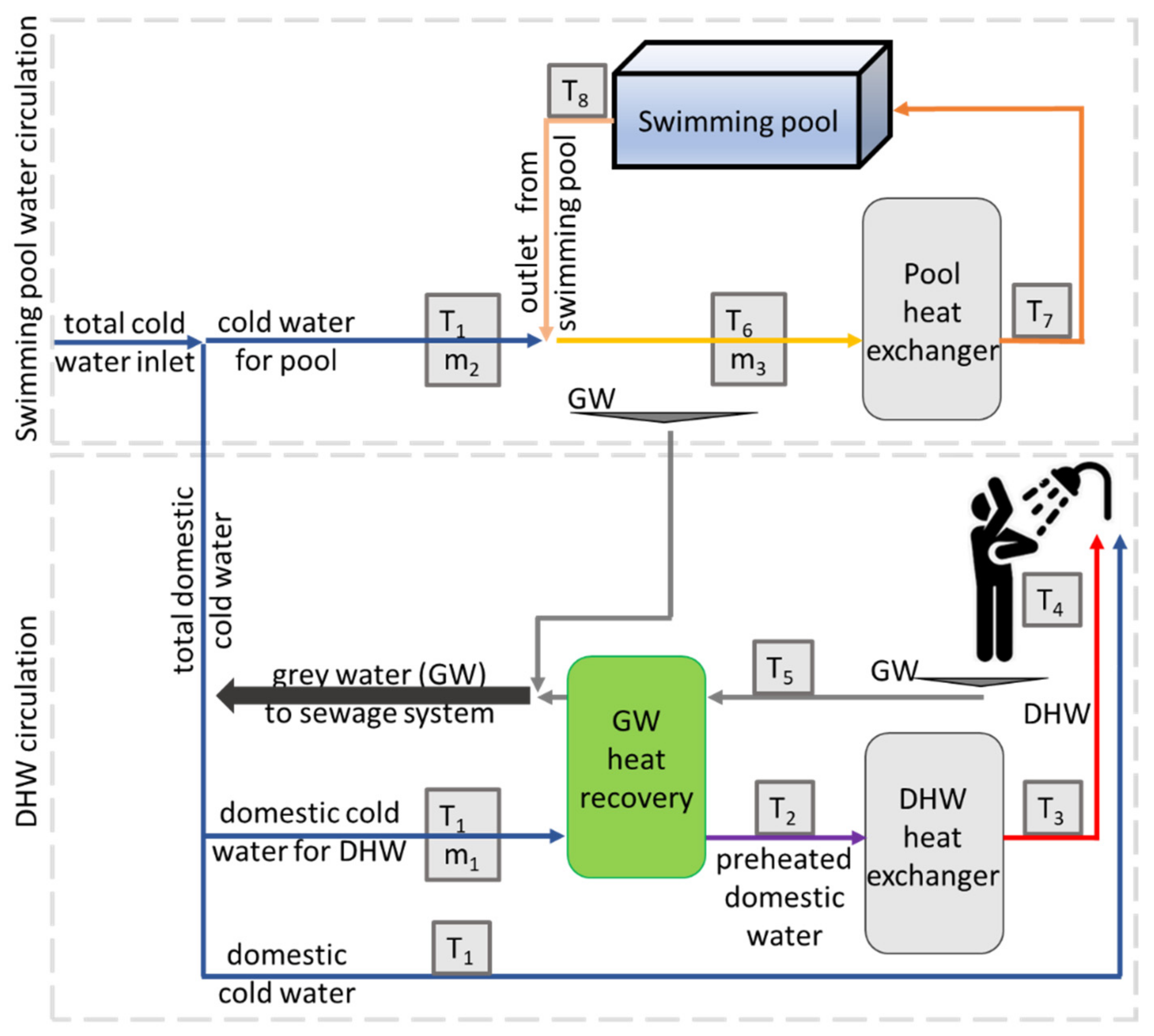

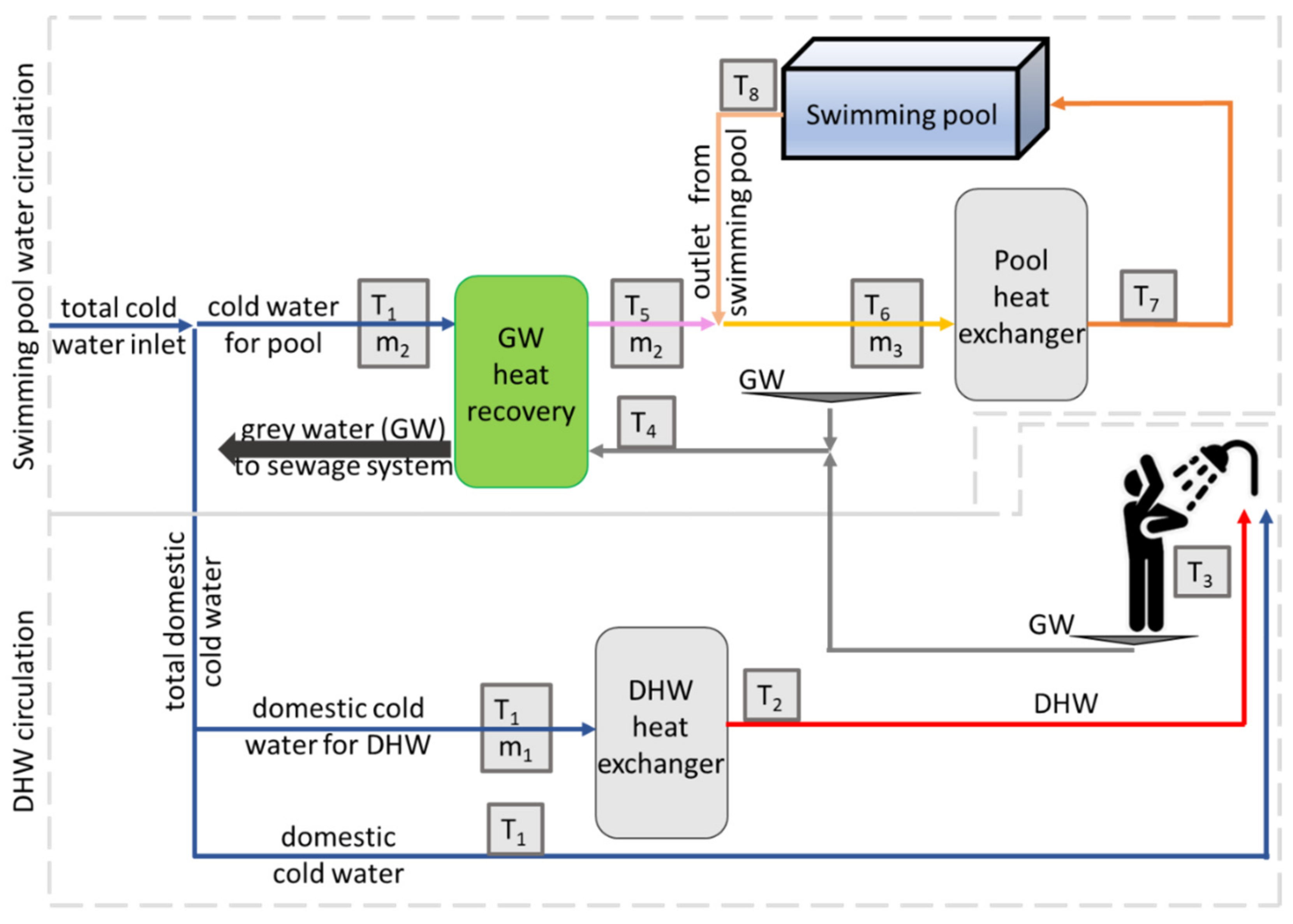

4. Case Study of Heat Recovery System for Swimming Pool

- -

- A sports swimming pool—dimensions 25 m × 16 m, depth from 1.80 m to 2.20 m and water temperature 27 °C [24]; it is divided into 6 tracks, one of which is shallow and is used for training and swimming lessons;

- -

- A recreational swimming pool—with dimensions of 16 m × 9 m, depth from 0.90 m to 1.30 m and water temperature of 30 °C [24]; equipped with water jets, geysers and massage couches;

- -

- Three water slides 52 m long (inner for children), 136 m (external), 108 m (external), with visual and acoustic elements;

- -

- Paddling pool with small slide (children’s pool)—with theoretical water temperature at 33 °C;

- -

- Two jacuzzis, i.e., with octagonal hot water pools equipped with underwater massage jets—with water temperature at 36 °C [24].

4.1. Description of the Conducted Measurements

- Portable ultrasonic flow meter FLUXUS F601 provided by Flexim, DN 10 to DN 400, −30 to +130 °C;

- Portable ultrasonic flow meter Portaflow C provided by Fuji, DN 13 to DN 400, −40 to +100 °C;

- Wireless temperature measurement sensors provided by Wisensys, −50 to +150 °C.

4.2. Consideration of Standards in View of Energy Saving Analysis

- -

- For swimming pool

- -

- For recreational swimming pool with water slide

- -

- For children’s pool with water slide

- -

- For swimming pool

- -

- For recreational swimming pool with water slide and children’s pool with water slide

- a = 4.5 for swimming pool;

- a = 2.7 for the recreational pool with slide and for the children’s pool with slide.

4.3. Energy-Saving Analysis

4.3.1. Feasibility of Heat Recovery in the Analysed Swimming Pool

4.3.2. Heat Recovery from DHW for the Case Study in the Analysed Swimming Pool

4.3.3. Heat Recovery for Preheating the Pool Water in Case Study in the Analysed Swimming Pool

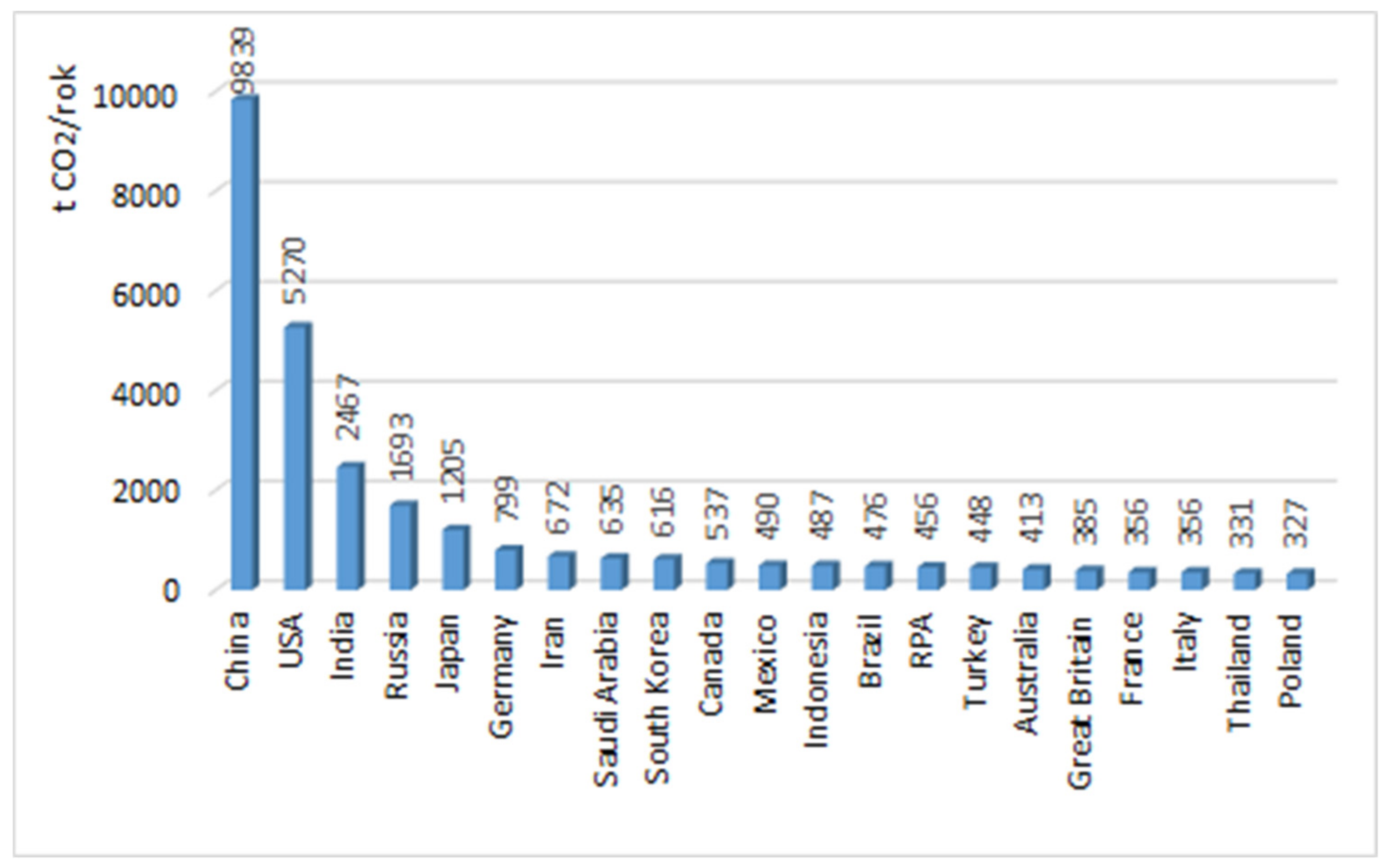

5. Environmental Impact of GWHR System in Case Study

5.1. Environmental Impact of Fossil Fuel Consumption

5.2. Air Pollutant for the Case Study in the Analysed Swimming Pool

6. Conclusions

- DHW daily consumption included in the range from 21.2 to 41.2 m3, the average daily consumption is 31.9 m3;

- DHW temperature included in the range from 33.7 to 51.1 °C, the average DHW temperature is 45.7 °C;

- Cold water temperature included in the range from 10.7 to 53.5 °C, the average DHW temperature is 14.5 °C.

- ①

- For DHW preheating, taking the measured flow and water temperatures as the basis for calculation;

- ②

- For DHW preheating, taking the flow rates and water temperatures from guidelines and standards as the basis for calculation;

- ③

- To preheat swimming pool water.

- For case 1—from 1.34 to 2.43 GJ per day, average 4.19 GJ per day, which gives average 45% energy saving;

- For case 2—from 3.25 to 5.20 GJ per day, average 4.23 GJ per day, which gives 40% energy saving;

- For case 3, depending on the type of swimming pool provide from 48 to 67% energy saving.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Barbato, M.; Cirillo, L.; Menditto, L.; Moretti, R.; Nardini, S. Geothermal energy application in Campi Flegrei Area: The case study of a swimming pool building. Int. J. Heat Technol. 2017, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, E.M.; Jorge, H.M.; Quintela, D.A. An approach to optimised control of HVAC systems in indoor swimming pools. Int. J. Sustain. Energy 2014, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization Guidelines for Safe Recreational Water Environments. Swimming Pools and Similar Environments. 2006, Volume 2. Available online: https://www.who.int/water_sanitation_health/bathing/srwe2full.pdf (accessed on 19 January 2019).

- Katsaprakakis, D.A. Comparison of swimming pools alternative passive and active heating systems based on renewable energy sources in Southern Europe. Energy 2015, 81, 738–753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Departament Infrastruktury Sportowej Ministerstwo Sportu i Turystyki. Pływalnie Kryte w Polsce. Inwentaryzacja Bazy Sportowej; Ministerstwo Sportu i Turystyki: Warsaw, Polska, 2015.

- Kannewischer, B. 301—Bäder—Grundlagen für Planung, Bau und Betrieb; Fachstelle Sportanlagen, Bundesamt für Sport BASPO: Magglingen, Switzerland, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- International Swimming Federation (FINA). Fina Facilities Rules 2017–2021, Part X; FINA: Lausanne, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Główny Urząd Statystyczny. Available online: https://stat.gov.pl/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Johansson, L.; Westerlund, L. Energy savings in indoor swimming-pools: Comparison between different heat-recovery systems. Appl. Energy 2001, 70, 281–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, P.; Wu, J.Y.; Wang, R.; Xu, Y.X. Analysis of indoor environmental conditions and heat pump energy supply systems in indoor swimming pools. Energy Build. 2011, 43, 1071–1080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für das Badewessen e.V. Baeder Atlas. Available online: http://www.baederatlas.com/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Leitfaden Energie in Hallen- und Freibädern, Programm Energie Schweiz, Bundesamt für Energie. Available online: www.bfe.admin.ch (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Verband Hallen- und Freibäder. Available online: https://vhf-gsk.ch/data/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- 2019 State of the UK Swimming Industry Report—Out Now. Available online: https://www.leisuredb.com/blogs/2019/6/7/2019-state-of-the-uk-swim-industry-report-out-now (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- André, A. 39 Stunning Swimming Pools in France You Won’t Believe Are Public. Available online: https://www.annieandre.com/amazing-public-swimming-pools-in-france/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Annuaire des Piscines Publiques. Available online: https://www.guide-piscine.fr/guide-des-piscines/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Willoughby, I. Many Municipalities Looking to Replace Old Pools and Stem Losses. Available online: https://english.radio.cz/many-municipalities-looking-replace-old-pools-and-stem-losses-8157498 (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Basic Study on Public and Communal Swimming Pools in Spain. Available online: https://www.eurospapoolnews.com/actualites_piscines_spas-en/55176-aofap,study,public,swimming,pools,spain.html (accessed on 20 April 2017).

- News and Press Releases. Available online: https://www.firabarcelona.com/en/press-release/piscina_s046/the-swimming-pool-sector-forecasts-a-turnover-of-1274-million-euros-6-more-than-in-2018/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Lamprecht, M.; Stamm, H.P. Sportaktivität und Sportkonsum der Schweizer Bevölkerung; Swiss Olympic Association/Sport-Toto-Gesellschaft: Berne, Switzerland, 2000; ISBN 3-9521335-4-X. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Lamprecht, M.; Fischer, A.; Stamm, H.P. Sportaktivität und Sportinteresse der Schweizer Bevölkerung; Bundesamt für Sport BASPO, Sport Schweiz: Magglingen, Switzerland, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Aufbereitung von Schwimm-und Badebeckenwasser—Teil 1: Allgemeine Anforderungen, DIN 19643-1—1997-04; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 1997.

- Aufbereitung von Schwimm-und Badebeckenwasser—Teil 1: Allgemeine Anforderungen. Treatment of Water of Swimming Pools and Baths—Part 1: General Requirements, DIN 19643-1—2012-11; Beuth: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Sokołowski, C. Wymagania Sanitarno-Higieniczne dla Krytych Pływalni; Polskie Zrzeszenie Inżynierów i Techników Sanitarnych: Wrocław, Polska, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizerischer Schwimmverband. Wettkampfanlagen in der Schweiz. Anforderungen, Erläuterungen und Beratung; Reglement 7.2.3; Swiss Swimming: Basel, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Wettkampfbestimmungen; Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen—Fachteil Synchronschwimmen (WB-FT SYN); Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen—Fachteil Schwimmen (WB-FT SW); Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen—Fachteil Wasserspringen (WB-FT SPR); Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2018.

- Bau- und Ausstattungs-Anforderungen für Wettkampfgerechte Schwimmsportstätten; Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2012.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen—Fachteil Wasserball (WB-FT WAB); Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2019.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen—Fachteil Schwimmen Freiwasser (WB-FT SW FS); Deutscher Schwimm-Verband e.V.: Berlin, Germany, 2017.

- Wettkampfbestimmungen für Schwimmen, Wettkampfbestimmungen Sparte Schwimmen Gesamtvorstand; Österreichischer Schwimmverband: Vienna, Austria, 2015.

- Maglionico, M.; Stojkov, I. Water consumption in a public swimming pool. Water Supply 2015, 15, 1304–1311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hof, A.; Morán-Tejeda, E.; Lorenzo-Lacruz, J.; Blázquez-Salom, M. Swimming pool Evaporative water loss and water use in the Balearic Islands (Spain). Water 2018, 10, 1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinopoulos, I.; Katsifarakis, K. Optimization of energy and water management of swimming pools. A case study in Thessaloniki, Greece. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2017, 38, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galvez-Martos, J.-L.; Schoenberger, H.; Styles, D. Reference Document on Best Environmental Management Practice in the building and construction sector. Final Report; European Commission, Joint Research Centre Institute for Prospective Technological Studies Contact: Brussels, Belgium, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Wyczarska-Kokot, J. The study of possibilities for reuse of washings from swimming pool circulation systems. Ecol. Chem. Eng. S 2016, 23, 447–459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampel, W.; Carlucci, S.; Aas, B.; Bruland, A. A proposal of energy performance indicators for a reliable benchmark of swimming facilities. Energy Build. 2016, 129, 186–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Styles, D.; Schoenberger, H.; Martos, J.L.G. Water management in the European hospitality sector: Best practice, performance benchmarks and improvement potential. Tour. Manag. 2015, 46, 187–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Union and European Commission. Energy audits and Energy Performance Certification; Report; European Union and European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Styles, D.; Schönberger, H.; Martos, J.L.G. Best Environmental Management Practice in the Tourism Sector; Publications Office of the European Union: Luxembourg, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hazell, F.; Nimmo, L. Best Practice Profile for Public Swimming Pools Maximising Reclamation and Reuse Best Practice Profile for Public Swimming Pools Maximising Reclamation and Reuse; Royal Life Saving Society (WA Branch): Mount Claremont, Australia, 2006; pp. 1–47. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.G. Measure 4: Swimming Pool Water Use Analysis by Observed Data and Long-Term Continuous Simulation; Conserve Florida Water Clearinghouse Department of Environmental Engineering Sciences, University of Florida: Gainesville, FL, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes, E.; Arce, L.; Salom, J. A review of domestic hot water consumption profiles for application in systems and buildings energy performance analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 81, 1530–1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Englart, S.; Jedlikowski, A. The influence of different water efficiency ratings of taps and mixers on energy and water consumption in buildings. SN Appl. Sci. 2019, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federation Internationale de Natation. Available online: https://www.fina.org/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Ligue Européenne de Natation. Available online: http://www.len.eu/# (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Kampel, W.; Aas, B.; Bruland, A. Energy-use in Norwegian swimming halls. Energy Build. 2013, 59, 181–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trianti-Stourna, E.; Spyropoulou, K.; Theofylaktos, C.; Droutsa, K.; Balaras, C.; Santamouris, M.; Asimakopoulos, D.; Lazaropoulou, G.; Papanikolaou, N. Energy conservation strategies for sports centers: Part A. Sports halls. Energy Build. 1998, 27, 109–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 9836: Performance Standards in Building—Definition and Calculation of Area and Space Indicators; International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2011.

- Rajagopalan, P.; McIntosh, A. A guide for Benchmarking Energy and the Indoor Environmental Quality of Aquatic Centres in Victoria; Aquatic and Recreation Victoria: Wellington, Australia, 2016; pp. 1–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rozporządzenie Ministra Infrastruktury z Dnia 14 Stycznia 2002 r. w Sprawie Określenia Przeciętnych Norm Zużycia Wody, no. 8 Pos. 70; Warsaw, Poland, 2002.

- Internationale Akademie für Bäder-, Sport- und Freizeitbauten e.V. (IAB). Fangstrasse 22—24, 59077 Hamm, Deutschland.

- Schramek, E.R. Taschenbuch für Heizung und Klimatechnik Einschließlich Warmwasser und Kältetechnik, 75th ed.; Oldenbourg Industrieverlag: München, Germany, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Piechurski, F. Ocena i analiza zużycia wody w różnych pływalniach krytych. Rynek Instal. 2016, 3. Available online: http://www.rynekinstalacyjny.pl/artykul/id4011,ocena-i-analiza-zuzycia-wody-w-roznych-plywalniach-krytych (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Definicja Wody Szarej. Available online: http://www.ecolife.com/define/grey-water.html (accessed on 20 March 2021).

- Odzysk Ciepła ze Ścieków w Krytych Pływalniach. Pływalnie i Baseny. 2013. Available online: http://plywalnieibaseny.pl/odzysk-ciepla-ze-sciekow-w-krytych-plywalniach (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Zhang, Q.; Fan, X.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Z. Utilization potential and economic feasibility analysis of bathing sewage and its heat generated in colleges and universities. Energy Procedia 2017, 142, 1244–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PN-EN 12056-1:2002 Systemy Kanalizacji Grawitacyjnej Wewnątrz Budynków—Część 1: Postanowienia Ogólne i Wymagania; Warsaw, Poland.

- Mazhar, A.R.; Liu, S.; Shukla, A. A key review of non-industrial greywater heat harnessing. Energies 2018, 11, 386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebersbach, J.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.T.; Polarczyk, I.; Danielewicz, J. Comparison of pools water heating systems. In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference Sustainable Energy and Environmental Protection, Sharjah, United Arab Emirates, 18–21 November 2019; pp. 542–547. [Google Scholar]

- Krajowa Agencja Poszanowania Energii. Koncepcja Przedprojektowa i Plan Funkcjonalno-Użytkowy dla Niskobudżetowego, Energooszczędnego Basenu; Krajowa Agencja Poszanowania Energii: Warsaw, Poland. Available online: https://cloud2.edupage.org/cloud1.edupage.org/cloud/8_PFU.pdf?z%3ATJaGKFwDbfv%2FCB59nbHEmpHxqofIMqOKHhLO4gkEkL2ZSzBigwMfkbqXLu7S0Z7L (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Cardoso, B.; Gaspar, A.R.; Góis, J.C.; Rodrigues, E. Energy and water consumption characterization of portuguese indoor swimming pools. In Proceedings of the CYTEF 2018 VII Congreso Ibérico, Ciencias Y Técnicas del Frío, Valencia, Spain, 19–21 June 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, E. Rozkład zużycia i źródła ciepła w obiektach basenowych. Rynek Instal. 2013, 1–2, 72–74. Available online: http://www.rynekinstalacyjny.pl/artykul/id3488,rozklad-zuzycia-i-zrodla-ciepla-w-obiektach-basenowych (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Fijewski, M.; Polarczyk, I.; Paduchowska, J. Analysis and simulation of the circulation pump operation. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polarczyk, I.; Fijewski, M. Impact of the circulation system on the energy balance of the building. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polarczyk, I.; Fijewski, M. Impact of the circulation system on domestic hot water consumption. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Żabnieńśka-Góra, A. Impact of external conditions on energy consumption in industrial halls. E3S Web Conf. 2017, 22, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brough, D.; Jouhara, H. The aluminium industry: A review on state-of-the-art technologies, environmental impacts and possibilities for waste heat recovery. Int. J. Thermofluids 2020, 1–2, 100007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malinauskaite, J.; Jouhara, H.; Czajczynska, D.; Stanchev, P.; Katsou, E.; Rostkowski, P.; Thorne, R.; Colón, J.; Ponsa, S.; Al-Mansour, F.; et al. Municipal solid waste management and waste-to-energy in the context of a circular economy and energy recycling in Europe. Energy 2017, 141, 2013–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kharmanda, G.; Sayegh, M.A. Reliability-based design optimization for heat flux analysis of composite modular walls using inverse reliability assessment method. Int. J. Thermofluids 2020, 1–2, 100008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czajczyńska, D.; Anguilano, L.; Ghazal, H.; Krzyżyńska, R.; Reynolds, A.; Spencer, N.; Jouhara, H. Potential of pyrolysis processes in the waste management sector. Therm. Sci. Eng. Prog. 2017, 3, 171–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savenkova, E.V.; Sayegh, M.A.; Bystryakov, A.Y.; Blokhina, T.K.; Karpenko, O. Utilization and recycling of municipal solid waste in a subarctic zone. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayegh, M.A.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A. Characteristics of Oder river water temperature for heat pump. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajski, K.; Danielewicz, J.; Brychcy, E. Performance evaluation of a gravity-assisted heat pipe-based indirect evaporative cooler. Energies 2020, 13, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudkiewicz, E.; Ludwińska, A.; Rajski, K. Implementation of greywater heat recovery system in hospitals. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhara, H.; Serey, N.; Khordehgah, N.; Bennett, R.; Almahmoud, S.; Lester, S.A.S.P. Investigation, development and experimental analyses of a heat pipe based battery thermal management system. Int. J. Thermofluids 2020, 1–2, 100004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnell, M.; Lundin, E.; Jeppson, U. Sustainability Analysis for Wastewater Heat Recovery—Literature Review. Sustain. Anal. Wastewater Heat Recovery 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayegh, M.A.; Hammad, M.; Faraa, Z. Comparison of two methods of improving dehumidification in air conditioning systems: Hybrid system (refrigeration cycle-rotary desiccant) and heat exchanger cycle. Energy Procedia 2011, 6, 759–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristensen, B.B.; Madsen, O.L.; Møller-Pedersen, B.; Nygaard, K. Classification of actions or inheritance also for methods. Comput. Vis. 1987, 156, 98–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jimenez, S.A.; Carrillo, V.; Alvarado, M.A. Swimming pool heating systems: A review of applied models. TECCIENCIA 2015, 10, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Skowroński, P. Raport Czyste Ciepło; Ministerstwo Klimatu: Warsaw, Poland, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Kancelaria Senatu. Emisja Gazów Wybrane Zagadnienia Dotyczące Emisji CO2 w Polsce. Opracowania Tematyczne OT–683; Kancelaria Senatu: Warsaw, Poland, 2020.

- KOBIZE. Krajowy Raport Inwentaryzacyjny 2019; KOBIZE: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Albulescu, C.T.; Artene, A.E.; Luminosu, C.T.; Tămășilă, M. CO2 emissions, renewable energy, and environmental regulations in the EU countries. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 27, 33615–33635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PPAL and DKT Expert-Kraków. Kryta Pływalnia w Strzelinie—Projekt Budowlany; Branża G-Technologie Cieplne: Cracov, Poland, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Golak, D. Praktyczny Aspekt Funkcjonowania Biogazowni na Przykładzie pływalni „Na fali” w Michałowie. 2019. Available online: http://plywalnieibaseny.pl/praktyczny-aspekt-funkcjonowania-biogazowni-na-przykladzie-plywalni-na-fali-w-michalowie/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Żarski, K. Projektowanie kotłowni wodnej. Bilans cieplny kotłowni wodnej. Rynek Instal. 2012, 12. Available online: http://www.rynekinstalacyjny.pl/artykul/id3466,projektowanie-kotlowni-wodnej-bilans-cieplny-kotlowni-wodnej?print=1 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Rodak, M. Kogeneracja—Gwarancją; Pływalnie i Baseny, AGM Grupa Mediowa: Ząbki, Poland, 2017; pp. 106–107. Available online: https://www.ces.com.pl/sites/default/files/pib_17_ces4.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Jarosiński, M.; Grzebielec, A. Analiza opłacalności systemu trójgeneracji w budynku sanatoryjnym. Rynek Instal. 2018, 10. [Google Scholar]

- Pawlak, M. Ekologiczne Rozwiązania w Wodnym Parku Tychy; Pływalnie i Baseny, AGM Grupa Mediowa: Ząbki, Poland, 2019; Volume 31. Available online: http://plywalnieibaseny.pl/ekologiczne-rozwiazania-w-wodnym-parku-tychy/ (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Rotimi, A.; Bahadori-Jahromi, A.; Mylona, A.; Godfrey, P.; Cook, D. Estimation and validation of energy consumption in UK existing hotel building using dynamic simulation software. Sustainability 2017, 9, 1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paduchowska, J.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Polarczyk, I. Energy-saving analysis of grey water heat recovery systems for student dormitory. E3S Web Conf. 2019, 116, 00056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słyś, D.; Kordana-Obuch, S. Financial analysis of the implementation of a Drain Water Heat Recovery unit in residential housing. Energy Build. 2014, 71, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Directive 2012/27/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2012 on Energy Efficiency. 2012, pp. 1–56. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2012:315:0001:0056:en:PDF (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Rashad, M.; Khordehgah, N.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Ahmad, L.; Jouhara, H. The utilisation of useful ambient energy in residential dwellings to improve thermal comfort and reduce energy consumption. Int. J. Thermofluids 2021, 9, 100059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaci, K.; Merzouk, M.; Merzouk, N.K.; El Ganaoui, M.; Sami, S.; Djedjig, R. Dynamic simulation of hybrid-solar water heated olympic swimming pool. Energy Procedia 2017, 139, 750–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietras-Szewczyk, M. Wybór technologii OZE do ogrzewania wody w basenach otwartych. Rynek Instal. 2015, 3, 62–67. [Google Scholar]

- Clot, M.R.; Rosa-Clot, P.; Tina, G.M. Submerged PV solar panel for swimming pools: SP3. Energy Procedia 2017, 134, 567–576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sayegh, M.A. The solar contribution to air conditioning systems for residential buildings. Desalination 2007, 209, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podgrzewanie Wody w Basenie—Jakie Rozwiązanie Wybrać? Available online: www.hewalex.pl/porady-i-wiedza/kolektory-sloneczne/podgrzewanie-wody-basenowej-jakie-rozwiazania-wybrac.html (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Jordaan, M.; Narayanan, R. A numerical study on various heating options applied to swimming pool for energy saving. Energy Procedia 2019, 160, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khordehgah, N.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Jouhara, H. Energy performance analysis of a PV/T system coupled with domestic hot water system. ChemEngineering 2020, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryś, K.; Bryś, T.; Sayegh, M.A.; Ojrzyńska, H. Characteristics of heat fluxes in subsurface shallow depth soil layer as a renewable thermal source for ground coupled heat pumps. Renew. Energy 2020, 146, 1846–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, S.N.; Mishra, A.; Dutta, A.K. International Conference on Recent Trends in Physics 2016 (ICRTP2016). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2016, 755, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratajczak, K.; Szczechowiak, E. Energy consumption decreasing strategy for indoor swimming pools—Decentralized ventilation system with a heat pump. Energy Build. 2020, 206, 109574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jouhara, H.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Khordehgah, N.; Ahmad, D.; Lipinski, T. Latent thermal energy storage technologies and applications: A review. Int. J. Thermofluids 2020, 5–6, 100039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahash, A.; Ochs, F.; Janetti, M.B.; Streicher, W. Advances in seasonal thermal energy storage for solar district heating applications: A critical review on large-scale hot-water tank and pit thermal energy storage systems. Appl. Energy 2019, 239, 296–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubiński, K.; Szabłowski, Ł. Dynamic model of solar heating plant with seasonal thermal energy storage. Renew. Energy 2020, 145, 2025–2033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ninikas, K.; Hytiris, N.; Emmanuel, R.; Aaen, B. Recovery and valorisation of energy from wastewater using a water source heat pump at the Glasgow subway: Potential for similar underground environments. Resources 2019, 8, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewitecka, K. Possibilities of heat energy recovery from greywater systems. E3S Web Conf. 2018, 30, 03003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pintér, R. Wastewater heat recovery systems: A simple, cost-effective way to help meet the renovation wave energy saving and decarbonisation targets. REHVA J. 2020, 60–63. Available online: https://www.rehva.eu/rehva-journal/chapter/wastewater-heat-recovery-systems-a-simple-cost-effective-way-to-help-meet-the-renovation-wave-energy-saving-and-decarbonisation-targets-1 (accessed on 19 March 2021).

- Energy Union Package—A Framework Strategy for a Resilient Energy Union with a Forward-Looking Climate Change Policy, COM(2015) 80 Final; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; pp. 1–21.

- European Commission, Report from the Commission to the European Parliament and the Council. Assessment of the Progress Made by Member States towards the National Energy Efficiency Targets for 2020 and towards the Implementation of the Energy Efficiency Directive 2012/27/EU as, vol. 24, no. 2015; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2015; p. 17. [Google Scholar]

- Airly Map. Available online: https://airly.org/map/pl/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Definicja Indeksów. Available online: https://www.airqualitynow.eu/pl/about_indices_definition.php (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Rachunki Ekonomiczne Środowiska; Główny Urząd Statystyczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2018.

- Europe’s Coal Power Collapse Exposes Steel Plants as Europe’s Biggest Emitters. Available online: https://ember-climate.org/project/ets-2019-release/ (accessed on 20 February 2021).

- Przyszły Miks Energetyczny Polski—Determinanty, Narzędzia i Prognozy; Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2019; Volume 6.

- Wartości Opałowe (WO) i Wskaźniki emisji CO2 (WE) w Roku 2015 do Raportowania w Ramach Systemu Handlu Uprawnieniami do Emisji za rok 2018; Krajowy Ośrodek Bilansowania i Zarządzania Emisjami: Warsaw, Poland, 2017; Volume 2. (In Polish)

- Krajowy Ośrodek Bilansowania i Zarządzania Emisjami and Instytut Ochrony Środowiska—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy. Krajowy Bilans Emisji Pyłów, Metali Ciężkich i TZO za Lata 2015–2017 w Układzie Klasyfikacji SNAP Raport syntetyczny; Krajowy Ośrodek Bilansowania i Zarządzania Emisjami and Instytut Ochrony Środowiska—Państwowy Instytut Badawczy: Warsaw, Poland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Krajowy Ośrodek Bilansowania i Zarządzania Emisjami and Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny. Wskaźniki Emisji Zanieczyszczeń ze Spalania Paliw, Kotły o Nominalnej Mocy Cieplnej do 5 MW; Krajowy Ośrodek Bilansowania i Zarządzania Emisjami and Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny: Warsaw, Poland, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Paris Agreement; United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change: Paris, France, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kancelaria Sejmu, Ustawa z Dnia 17 lipca 2009 r. o Systemie Zarządzania Emisjami Gazów Cieplarnianych i Innych Substancji; Warsaw, Poland, 2009. Available online: http://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20091301070/T/D20091070L.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2021).

| Water Consumption Target | L/Person | Share in % |

|---|---|---|

| Filling the pool | 5–10 | 4% |

| Constant water inflow to the pools adapted to the number of users (at least 30 L/person) Average limits: | 50 | 28% |

| Shower before and after bathing | 50–80 | 37% |

| Water consumption for toilets, handbasins, dry cleaners, canteens | 40–70 | 31% |

| Total water consumption | 145–210 | 100% |

| Water Consumption Target | L/Person |

|---|---|

| Indoor swimming pool | 160 |

| Outdoor swimming pool | |

| (a) sports | 200 |

| (b) for mass use | 400 |

| Water Consumption Target | L/Person | Temperature in °C |

|---|---|---|

| Sports facilities | 50–70 | 45 |

| Indoor swimming pool | 50 | 40 |

| Pool Type | Pool Basin Size in m | Water Surface Area in m2 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Sports pool + Recreation pool | 25 × 12.5 - | in both pools 372.5 |

| B | Sports pool | 25 × 12.5 | 312.5 |

| Recreation pool | irregular | 520 | |

| Paddling pools | irregular | 70 | |

| Whirlpool 1 piece | round | 1.3 | |

| Whirlpool 2 piece | round | 2.6 | |

| Outdoor | - | 626 | |

| Cooling pool | - | 11 |

| Source of GW in Swimming Pool | DHW in °C | GW Temperature in °C |

|---|---|---|

| Showers, handbasins | 39–42 | 28–41 |

| Filter rinsing | - | 25–35 |

| Swimming pool water losses | - | 25–35 |

| Swimming Pool Characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pool dimensions | 25 m × 16 m | |||

| Water surface | 400 m2 | |||

| Pool depth | 1.8–2.2 m | |||

| Pool volume | 800 m3 | |||

| Water temperature | 27 °C | |||

| Water supply to the basin | Bottom channels | |||

| Daily operating time of the installation | 24 h | |||

| Max. number of swimmers | 90 person/h | |||

| Fresh water volume | 42.62 m3 | |||

| Attractions | - | |||

| Requirements of simplified method [24] | Requirements of accurate method [24] | DIN 1997 [22] | DIN 2012 [23] | |

| Filtration efficiency | 160.00 m3/h | 177.60 m3/h | 177.60 m3/h | 177.60 m3/h |

| Filtration rate | 20.95 m/h | 23.25 m/h | 23.25 m/h | 23.25 m/h |

| Amount of backwater to rinse 1 filter | 15.27 m3 | 15.27 m3 | 15.27 m3 | 10.18 m3 |

| Equalising tank—active capacity | 31.25 m3 | 30.46 m3 | 30.46 m3 | 25.37 m3 |

| Recreational Pool Characteristics | ||||

| Pool dimensions | 16 m × 9 m | |||

| Water surface | 144 m2 | |||

| Pool depth | 0.9–1.3 m | |||

| Pool volume | 158.4 m3 | |||

| Water temperature | 30 °C | |||

| Water supply to the basin | Bottom channels | |||

| Daily operating time of the installation | 24 h | |||

| Max. number of swimmers | 35 person/h | |||

| Fresh water volume | 15.34 m3 | |||

| Attractions | slide | |||

| Requirements of simplified method [24] | Requirements of accurate method [24] | DIN 1997 [22] | DIN 2012 [23] | |

| Filtration efficiency | 93.60 m3/h | 141.56 m3/h | 141.56 m3/h | 141.56 m3/h |

| Filtration rate | 18.38 m/h | 27.80 m/h | 27.80 m/h | 27.80 m/h |

| Amount of backwater to rinse 1 filter | 15.27 m3 | 15.27 m3 | 15.27 m3 | 10.18 m3 |

| Equalising tank—active capacity | 22.79 m3 | 21.66 m3 | 21.66 m3 | 16.57 m3 |

| Children’s Pool Characteristics | ||||

| Pool dimensions | 4 m × 4 m assumption | |||

| Water surface | 16 m2 | |||

| Pool depth | 0.3–0.6 m assumption | |||

| Pool volume | 7.2 m3 | |||

| Water temperature | 33 °C | |||

| Water supply to the basin | Bottom channels | |||

| Daily operating time of the installation | 24 h | |||

| Max. number of swimmers | 4 person/h | |||

| Fresh water volume | 1.70 m3 | |||

| Attractions | little slide | |||

| Requirements of simplified method [24] | Requirements of accurate method [24] | DIN 1997 [22] | DIN 2012 [23] | |

| Filtration efficiency | 11.20 m3/h | 60.00 m3/h | 60.00 m3/h | 60.00 m3/h |

| Filtration rate | 4.56 m/h | 24.44 m/h | 24.44 m/h | 24.44 m/h |

| Amount of backwater to rinse 1 filter | 7.37 m3 | 7.37 m3 | 7.37 m3 | 4.91 m3 |

| Equalising tank—active capacity | 8.47 m3 | 8.05 m3 | 8.05 m3 | 5.60 m3 |

| GWHR System for DHW | Energy Savings in GJ per Day | Energy Savings in % | ||||

| Min. | Max. | Average | Min. | Max. | Average | |

| 1.34 | 2.43 | 1.87 | 34 | 48 | 45 | |

| Swimming Pool | |

|---|---|

| Max. number of swimmers | 90 person/h |

| Recreational Pool | |

| Max. number of swimmers | 35 person/h |

| Children’s Pool | |

| Max. number of swimmers | 4 person/h |

| Total number of swimmers | 129 person/h |

| Domestic cold water temperature T1 | 10 °C |

| Preheated domestic water temperature T2 | 30 °C |

| DHW temperature T3 | 60 °C |

| Showers water temperature T4 | 40 °C |

| Min. water consumption | 50 L/person |

| Max. water consumption | 80 L/person |

| Open time (assumed) | 12 h |

| Average use of the pool (assumed) | 50% |

| GWHR System for DHW | DHW Consumption in m3/h | Energy Savings in GJ per Day | Savings in % | ||||

| Min. | Max. | Average | Min. | Max. | Average | ||

| 3.23 | 5.16 | 4.19 | 3.25 | 5.20 | 4.23 | 40 | |

| GWHR System for Pool Preheating | Water Amount in m3/Day | Energy Savings in GJ per Day | Savings in % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Swimming pool | 42.62 | 1.79 | 67 |

| Recreational pool | 15.34 | 0.64 | 56 |

| Children’s pool | 1.70 | 0.07 | 48 |

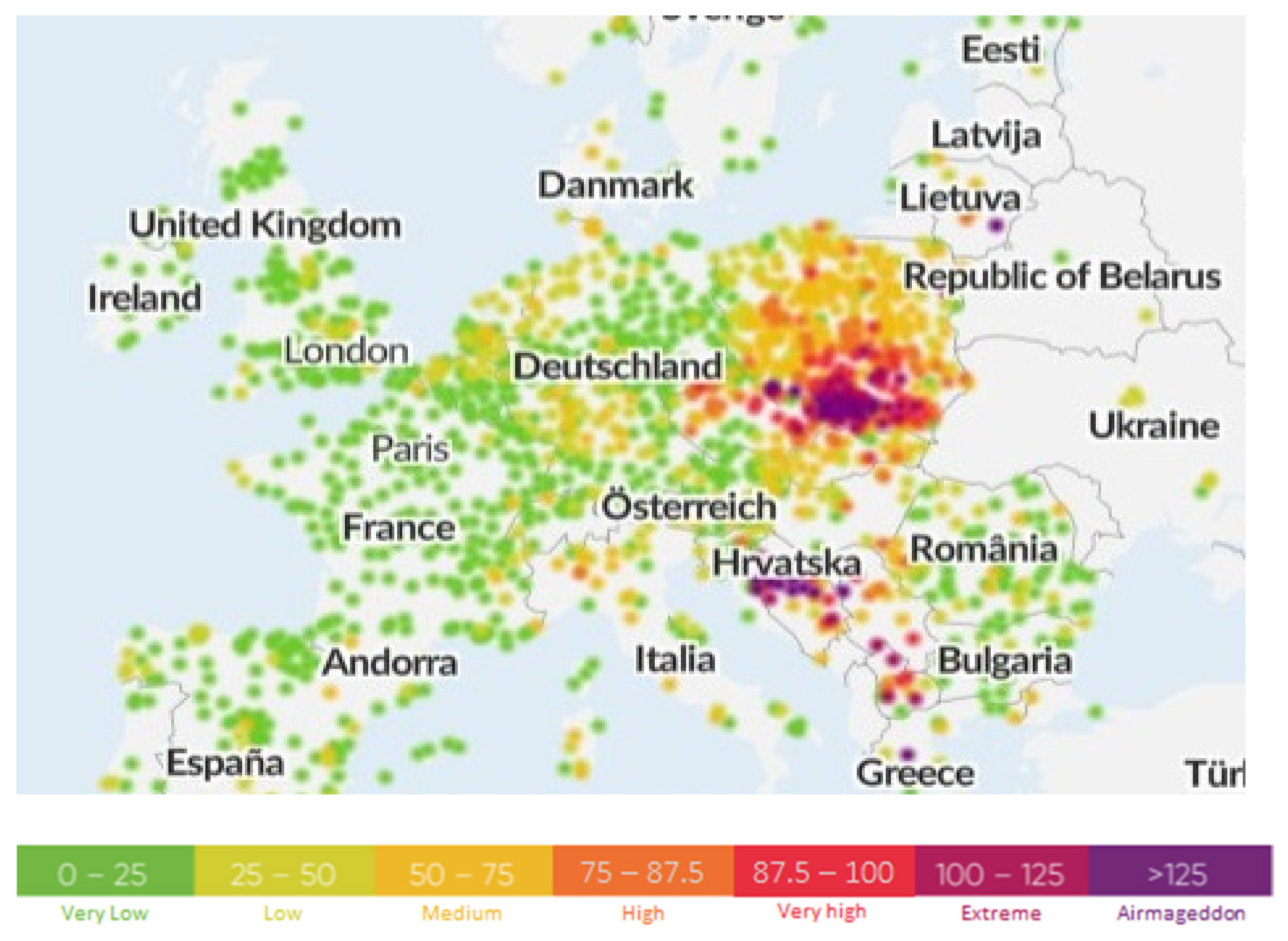

| Country | Poland | Germany | Czech Republic | Slovakia | Austria | Switzerland | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Air Pollutant | |||||||

| CO NO2 SO2 | 0–50 | 0–50 | 0–50 | 0–50 | 0–50 | 0–50 | |

| Dust | 0–125 | 0–50 | 0–100 | 0–75 | 0–75 | 0–75 | |

| Heat Source | Fuel | CV in MJ/kg | CO2 EF in kg/GJ |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHP plants | hard coal brown coal | 21.42 8.99 | 93.46 107.13 |

| Industrial CHP plants | hard coal | 22.94 | 94.66 |

| Heating plants | hard coal brown coal | 21.74 9.02 | 94.94 106.62 |

| Pollutants in kg/GJ | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| CO2 | NOX | SOX | Dust |

| 96.935 | 0.22 | 0.41 | 0.09 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liebersbach, J.; Żabnieńska-Góra, A.; Polarczyk, I.; Sayegh, M.A. Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools. Energies 2021, 14, 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144221

Liebersbach J, Żabnieńska-Góra A, Polarczyk I, Sayegh MA. Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools. Energies. 2021; 14(14):4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144221

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiebersbach, Joanna, Alina Żabnieńska-Góra, Iwona Polarczyk, and Marderos Ara Sayegh. 2021. "Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools" Energies 14, no. 14: 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144221

APA StyleLiebersbach, J., Żabnieńska-Góra, A., Polarczyk, I., & Sayegh, M. A. (2021). Feasibility of Grey Water Heat Recovery in Indoor Swimming Pools. Energies, 14(14), 4221. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144221