European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Green Jobs

2.2. Green Growth

2.3. Green Jobs, Technovation and Wellbeing

3. Methodology

4. Green Jobs Generation

4.1. Macroeconomics View

4.1.1. An Overview

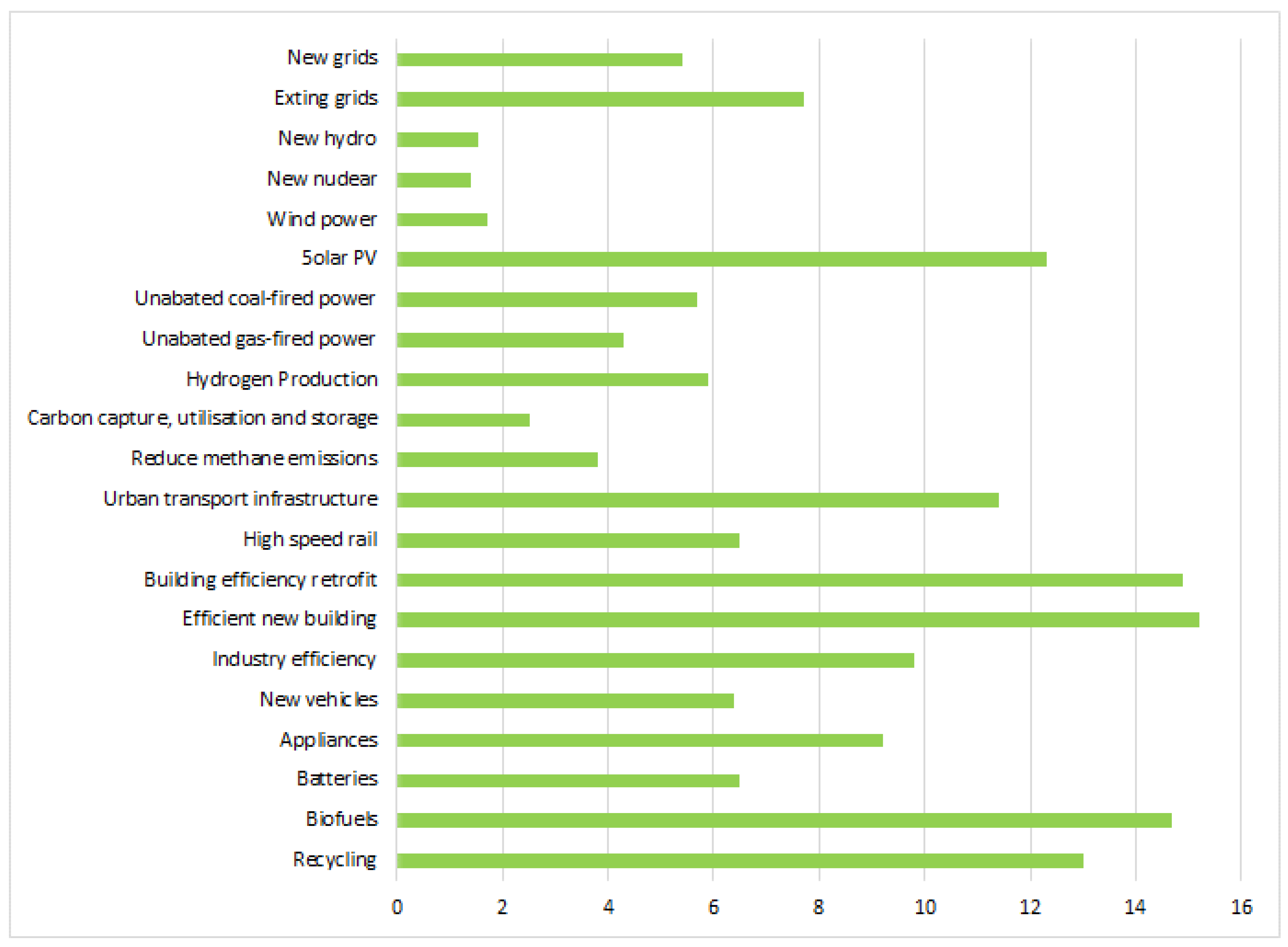

4.1.2. Cross-Cutting Lines of Action for a Green Spain

4.1.3. Green Recovery Plans—Cross Country View

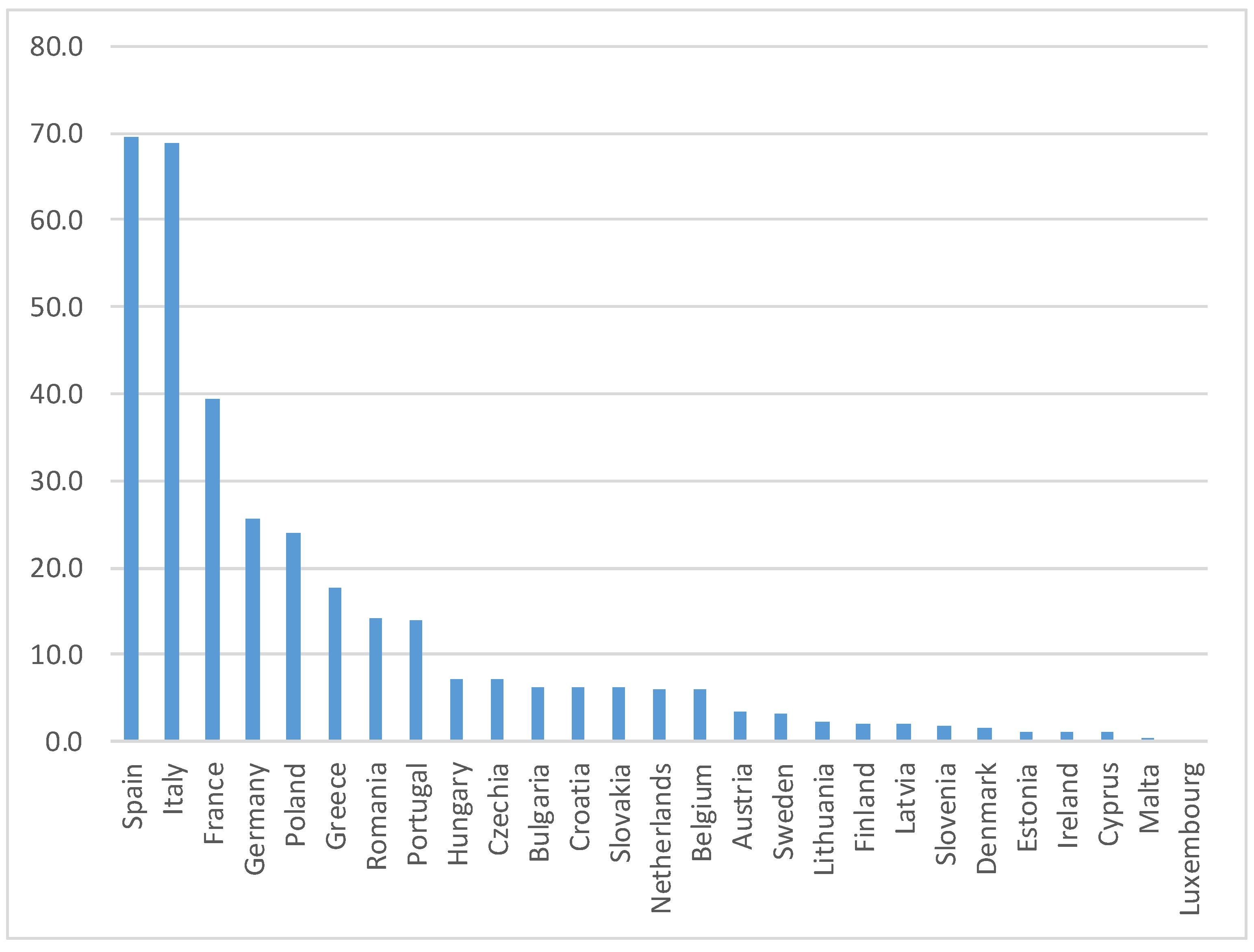

4.1.4. Green Jobs to Generate in Spain

4.2. Microeconomics View

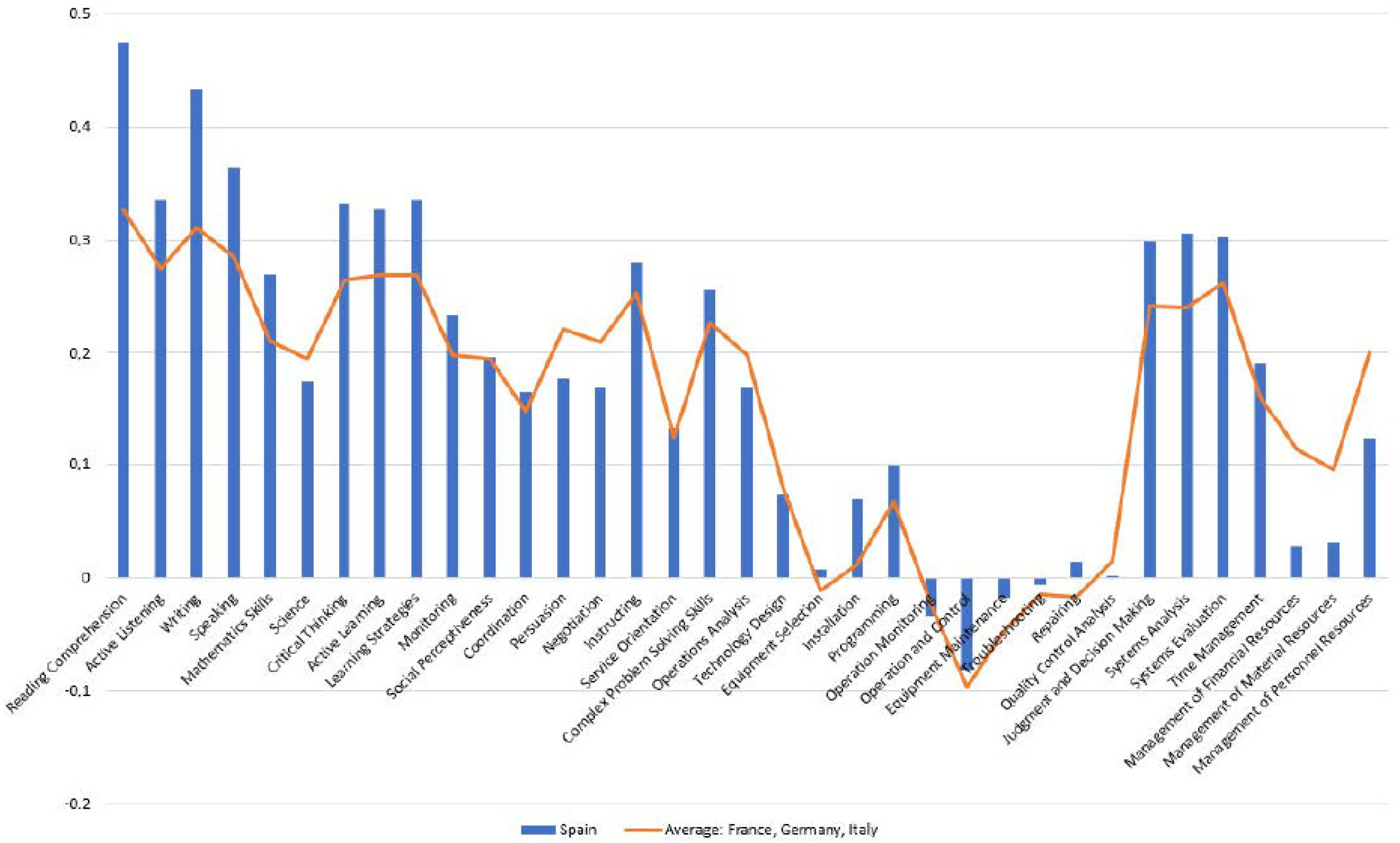

4.2.1. Green Jobs and Skills

4.2.2. Harmonisation and Unit of Measure Used

5. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Renewal of business & economic thought after the globalization. Bajo Palabra 2020, 24, 293–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. In Managing the Risks of Extreme Events and Disasters to Advance Climate Change Adaptation: Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2012.

- SDG agenda 2030. Transforming our World. The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development|Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Available online: Un.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- OECD. The Economy of Well-Being. The Economy of Well-Being—OECD. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote=SDD/DOC(2019)2&docLanguage=En#:~:text=The%20%E2%80%9CEconomy%20of%20Well%2Dbeing,2 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- WEF. Wellbeing Economy Alliance. About—Wellbeing Economy Alliance. Available online: https://wellbeingeconomy.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. European Green Deal. A European Green Deal—European Commission. Available online: Europa.eu (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Parliament. Multiannual Finance Framework. El Marco Financiero Plurianual—Fichas Temáticas Sobre la Unión Europea—Parlamento Europeo. Available online: Europa.eu (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. The European Green Deal COM/2019/640 Final. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=COM%3A2019%3A640%3AFIN (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Heredia Yzquierdo, J.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. The European transition to a green energy production model: Italian feed-in tariffs scheme & Trentino Alto Adige mini wind farms case study. Small Bus. Int. Rev. 2020, 4, 39–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Trincado, E. Business and labour culture changes in digital paradigm. Cogito 2020, 12, 225–243. [Google Scholar]

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable; Ramdom House: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Bagus, P.; Peña-Ramos, J.A.; Sánchez-Bayón, A. COVID-19 and the Political Economy of Mass Hysteria. Int. J. Env. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Soto, J.H.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Bagus, P. Principles of Monetary & Financial Sustainability and Wellbeing in a Post-COVID-19 World: The Crisis and Its Management. Sustainability 2021, 13, 4655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Commission. Recovery Plan for Europe. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/strategy/recovery-plan-europe_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- EUR-Lex. Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 Establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility. 2021. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A32021R0241 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Vicepresidencia del Gobierno y Ministerio de Asuntos Económicos y Transformación Digital. Plan de Recuperación, Transformación y Resiliencia. Available online: https://portal.mineco.gob.es/es-es/ministerio/areas-prioritarias/Paginas/PlanRecuperacion.aspx (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- International Labour Organization (ILO). What Is a Green Job? Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/news/WCMS_220248/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Eur-Lex. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and the Council Establishing the Framework for Achieving Climate Neutrality and Amending Regulation (EU) 2018/1999 (European Climate Law). Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?qid=1588581905912&uri=CELEX:52020PC0080 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Ecologic-EU. Climate Laws in Europe. Good Practices in Net-Zero Management. Available online: Ecologic.eu (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Developing a Sustainable Blue Economy in the European Union. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_2341 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Towards Zero Pollution for Air, Water and Soil. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_21_2345 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Organic Action Plan. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/food-farming-fisheries/farming/organic-farming/organic-action-plan_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. Fundamentos de Derecho Comparado y Global: ¿cabe un orden común en la globalización? Boletín Mex. Derecho Comp. 2014, 141, 1021–1051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- International Labour Organization (ILO). Guidelines for a Just Transition towards Environmentally Sustainable Economies and Societies for All. Available online: https://www.ilo.org/global/topics/green-jobs/publications/WCMS_432859/lang--en/index.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sánchez-Bayón, A.; García-Vaquero, M.; Lominchar, J. Wellbeing Economics: Beyond the Labour compliance & challenge for business culture. J. Leg. Ethical Regul. Issues 2021, 24, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bowen, A.; Kuralbayeva, K.; Tipoe, E.L. Characterizing green employment: The impacts of ‘greening’ on workforce composition. Energy Econ. 2018, 72, 263–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Consoli, G.; Marin, A.; Marzucchi, A.; Vona, F. Do green jobs differ from non-green jobs in terms of skills and human capital? Res. Policy 2016, 45, 1046–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lobisger, M.; Rutzer, C. Jobs with Green Potential in Switzerland: Demand and Possible Skills Shortages Jobs with Green Potential in Switzerland: Demand and Possible Skills Shortages; WWZ Working Papers-University of Basel: Basel, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez-Fernández, C.; Hinojosa, C.; Miranda, G. Green Jobs and Skills: The Local Labour Market Implications of Addressing Climate Change. Working Document-CFE/LEED-OECD. 2010. Available online: www.oecd.org/dataoecd/54/43/44683169.pdf?contentId=44683170 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- UK Office of National Statistics. The Challenges of Defining a “Green Job”. Available online: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/environmentalaccounts/methodologies/thechallengesofdefiningagreenjob (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Eurostat. Environmental Economy Statistics on Employment and Growth. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Environmental_economy_–_statistics_on_employment_and_growth (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Measuring Green Jobs. Available online: https://www.bls.gov/green/home.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- O*NET. U.S. Department of Labour. Available online: https://www.onetcenter.org/dictionary/22.0/excel/green_occupations.html (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- O*NET Online. Available online: https://www.onetonline.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- OECD. Towards Green Growth. 2021. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/greengrowth/48012345.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- European Commission. Basics Green Economy [WWW Document]. 2016. Available online: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/basics/green-economy/resources/index_en.htm (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- World Bank. Inclusive Green Growth, the Pathway to Sustainable Development. 2012. Available online: worldbank.org (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- UNEP. Towards a Green Economy: Pathways to Sustainable Development and Poverty Eradication. 2011. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=126&menu=35 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Grand, M.C. Carbon emission targets and decoupling indicators. Ecol. Indic. 2016, 67, 649–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tapio, P. Towards a theory of decoupling: Degrees of decoupling in the EU and the case of road traffic in Finland between 1970 and 2001. Transp. Policy 2005, 12, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Akizu-Gardoki, O.; Bueno, G.; Wiedmann, T.; Lopez-Guede, J.M.; Arto, I.; Hernandez, P.; Moran, D. Decoupling between human development and energy consumption within footprint accounts. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 202, 1145–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bithas, K.; Kalimeris, P. Unmasking decoupling: Redefining the Resource Intensity of the Economy. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 619, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonaiuti, M. Are we entering the age of involuntary degrowth? Promethean technologies and declining returns of innovation. J. Clean. Prod. Technol. Degrowth 2018, 197, 1800–1809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreau, V.; Vuille, F. Decoupling energy use and economic growth: Counter evidence from structural effects and embodied energy in trade. Appl. Energy 2018, 215, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- EEA. Trends and Projections in Europe 2018. In Tracking Progress towards Europe’s Climate and Energy Targets (No. 16/2018); European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. A Clean Planet for All. In A European Strategic Long-Term Vision for a Prosperous, Modern, Competitive and Climate Neutral (COM No. 773); European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- VV.AA. Defining a New Economic Paradigm: The Report of the High-Level Meeting on Wellbeing and Happiness. 2012. Available online: https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/index.php?page=view&type=400&nr=617&menu=35 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- World Happiness Report 2020. 2020. Available online: https://s3.amazonaws.com/happiness-report/2020/WHR20.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sánchez-Bayón, A. A history of HR and its digital transformation: From Fordism to talentism and happiness management. Rev Asoc. Española Espec. Med. Trab. 2020, 29, 198–214. [Google Scholar]

- Nordstrom, K.; Ridderstrale, J. Funky Business: Talent Makes Capital Dance; Pitman Publishing: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Cubeiro, J.L. Del Capitalismo al Talentismo; University of Deusto: Bilbao, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- European Commission. Recovery and Resilience Facility. Available online: https://ec.europa.eu/info/business-economy-euro/recovery-coronavirus/recovery-and-resilience-facility_en (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- E3G and Wuppertal Institute. Green Recovery Tracker. Available online: https://experience.arcgis.com/experience/f2700c9b597a4aababa4c80e732c6c5c/page/page_13/?views=view_16 (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- IEA and International Monetary Fund. Sustainable Recovery: World Energy Outlook. Sustainable Recovery—Analysis—IEA. Available online: https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/c3de5e13-26e8-4e52-8a67-b97aba17f0a2/Sustainable_Recovery.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Skills-OVATE. Skills Online Vacancy Analysis Tool for Europe. Available online: https://www.cedefop.europa.eu/en/data-visualisations/skills-online-vacancies/skills/occupations (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- OECD. Skills Statistics by Country STAT. 2018. Available online: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=SKILLS_2018_TOTAL# (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- CEDEFOP. Skills for Green Jobs. Skills for Green Jobs: 2018 Update Cedefop. Available online: europa.eu (accessed on 15 May 2021).

- Sikora, A. European Green Deal—Legal and Financial Challenges of Climate Change. ERA Forum 2021, 4, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sulich, A.; Rutkowska, M.; Pop, L. Green jobs, definitional issues, and the employment of young people: An analysis of three European Union countries. J. Jenvman 2020, 262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dell’Anna, F. Green jobs and energy efficiency as strategies for economic growth and the reduction of environmental impacts. Energy Policy 2021, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Green Jobs USA as of May 2021 | Employment (2019) | Projected Job Openings (2019–2029) | Projected Growth (2019–2029) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sustainability Specialists | 1,316,800 | 128,000 | much faster than average (8% or higher) |

| Landscaping and Groundskeeping Workers | 1,188,000 | 158,900 | much faster than average (8% or higher) |

| First-Line Supervisors of Production and Operating Workers | 648,900 | 56,900 | little or no change |

| Inspectors, Testers, Sorters, Samplers and Weighers | 590,100 | 48,300 | decline (−1% or lower) |

| Plumbers, Pipefitters and Steamfitters | 490,200 | 49,800 | average (3–4%) |

| Financial and Investment Analysts | 487,800 | 38,600 | Faster than average |

| Training and Development Specialists | 327,900 | 33,700 | much faster than average (8% or higher) |

| Sales Rep., Wholesale and Manufacturing, Tech and Scientific Products | 321,000 | 30,700 | average (3–4%) |

| Mechanical Engineers | 316,300 | 19,200 | average (3–4%) |

| Chief Sustainability Officers | 287,900 | 13,900 | decline (−1% or lower) |

| Production Workers, All Other | 238,600 | 24,700 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Energy Engineers, Except Wind and Solar | 170,100 | 10,300 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Architects, Except Landscape and Naval | 129,900 | 8700 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Mixing and Blending Machine Setters, Operators and Tenders | 128,000 | 13,300 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Career/Technical Education Teachers, Postsecondary | 124,100 | 9400 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Industrial Ecologists | 90,900 | 8900 | much faster than average (8% or higher) |

| Machine Feeders and Offbearers | 62,900 | 7000 | little or no change |

| Separating, Filtering, Clarifying, Precipitating, Operators and Tenders | 53,100 | 5400 | average (3–4%) |

| Materials Engineers | 27,500 | 1500 | slower than average (1–2%) |

| Foundry Mold and Coremakers | 17,600 | 1400 | decline (−1% or lower) |

| Lever Policies and Components | EUR Billion 2021–2023 | % |

|---|---|---|

| I. Urban and rural agenda, agricultural development and the fight against depopulation | 14.4 | 20.70% |

| 1. Action Plan for sustainable, safe and connected mobility in urban and metropolitan areas | 6.53 | 9.40% |

| 2. Housing rehabilitation and urban renewal plan | 6.82 | 9.80% |

| 3. Green and digital transformation of agri-food and fisheries industries | 1.05 | 1.50% |

| II. Resilient infrastructures and ecosystems | 10.4 | 15% |

| 4. Ecosystems and biodiversity conservation and restoration | 1.64 | 2.40% |

| 5. Coastal area and water resources preservation | 2.09 | 3% |

| 6. Sustainable, safe and connected mobility | 6.66 | 9.60% |

| III. A fair and inclusive energy transition | 6.38 | 9.20% |

| 7. Renewable energies implementation and integration | 3.16 | 4.50% |

| 8. Electrical infrastructures, promotion of smart networks and deployment of flexibility and storage | 1.36 | 2% |

| 9. Renewable hydrogen roadmap and sectoral integration | 1.55 | 2.20% |

| 10. Fair transition strategy | 0.3 | 0.40% |

| IV. A public administration for the 21st century | 4.31 | 6.20% |

| 11. Modernisation of public administration | 4.31 | 6.20% |

| V. Modernisation and digitalisation of industry and SMEs, entrepreneurship and business environment, recovery and transformation of tourism and other strategic sectors | 16.07 | 23.10% |

| 12. Industrial Policy Spain 2030 | 3.78 | 5.40% |

| 13. Fostering SME growth | 4.89 | 7% |

| 14. Modernisation and competitiveness of the tourism sector | 3.4 | 4.90% |

| 15. Digital connectivity, cybersecurity, 5G deployment | 3.99 | 5.70% |

| VI. Promotion of science and innovation and strengthening of the capabilities of the National Health System | 4.94 | 7.10% |

| 16. National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence | 0.5 | 0.70% |

| 17. Institutional reform and capacity building in the national science, technology and innovation system | 3.38 | 4.90% |

| 18. Renewal and expansion of the capabilities of the National Health System | 1.06 | 1.50% |

| VII. Education and knowledge, lifelong learning and capacity building | 7.31 | 10.50% |

| 19. National Plan for Digital skills | 3.59 | 5.20% |

| 20. Strategic plan for Vocational Training | 2.07 | 3% |

| 21. Modernisation and digitalisation of the education system, including early years education from age 0 to 3 | 1.64 | 2.40% |

| VIII. The new care economy and employment policies | 4.85 | 7% |

| 22. Emergency plan for the care economy and reinforcement of inclusion policies | 2.49 | 3.60% |

| 23. New public policies for a dynamic, resilient and inclusive labour market | 2.36 | 3.40% |

| IX. Promotion of the culture and sports industries | 0.82 | 1.20% |

| 24. Valorization of the cultural industry | 0.32 | 0.50% |

| 25. Spain audio-visual hub | 0.2 | 0.30% |

| 26. Sports industry promotion plan | 0.3 | 0.40% |

| X. Modernisation of the tax system for inclusive and sustainable growth | 0 | 0% |

| 27. Measures and actions to prevent and combat tax fraud | 0 | 0% |

| 28. Tax reform for the 21st century | 0 | 0% |

| 29. Improving the effectiveness of public spending | 0 | 0% |

| 30. Long-term sustainability of the public pension system within the framework of the Toledo Pact | 0 | 0% |

| Total | 69.52 | |

| Total Green Initiatives | 36.98 | 53% |

| The 20 Programmes Driving Investment | EUR Billion 2021–2023 |

|---|---|

| 1. Safe, sustainable and connected mobility strategy | 13.2 |

| 2. Housing rehabilitation and urban renewal programme | 6.82 |

| 3. Modernisation of the public administration | 4.31 |

| 4. SMEs Digitalisation Plan | 4.06 |

| 5. 5G roadmap | 3.99 |

| 6. New Spain 2030 industrial policy and circular economy strategy | 3.78 |

| 7. National Plan for Digital Skills | 3.59 |

| 8. Modernisation and competitiveness of the tourism industry | 3.4 |

| 9. Development of the national science and innovation system | 3.38 |

| 10. Implementation and integration of renewable energies | 3.16 |

| 11. New care economy | 2.49 |

| 12. New public policies for a dynamic, resilient and inclusive labour market | 2.36 |

| 13. Preservation of coastal areas and water resources | 2.09 |

| 14. Strategic plan for vocational training | 2.07 |

| 15. Modernisation and digitalisation of the education system | 1.64 |

| 16. Conservation and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity | 1.64 |

| 17. Renewable hydrogen roadmap | 1.55 |

| 18. Electrical infrastructure, smart networks and storage | 1.36 |

| 19. Renovation and modernisation of the health system | 1.06 |

| 20. National Strategy for Artificial Intelligence | 0.5 |

| Total | 69.52 |

| Total Green Initiatives | 36.98 |

| The 20 Main Reforms of the Recovery Plan |

|---|

| 1. Climate Change and Energy Transition Law |

| 2. Development of a robust and flexible energy system, implementation and integration |

| of renewable energies |

| 3. Renewable hydrogen roadmap |

| 4. Resilience and adaptation of ecosystems, development and connectivity of green infrastructures |

| 5. Water Law and national water treatment, sanitation, efficiency, saving and reuse plan |

| 6. Modernisation of the agricultural and fisheries policy—soil protection and efficient use of water |

| 7. Waste policy and promotion of the circular economy |

| 8. Modernisation of the national science system and support for innovation |

| 9. Sustainable and connected mobility strategy |

| 10. New housing policy |

| 11. Modernisation of the justice system |

| 12. Modernisation and digitalisation of the public administration |

| 13. Better regulation and business environment—insolvency framework reform |

| 14. Modernisation and strengthening of the National Health System |

| 15. Modernisation and strengthening of the education, vocational training and university system |

| 16. New labour market public policies |

| 17. New care economy |

| 18. Reinforcement of inclusion policies and social services |

| 19. Modernisation and progressivity of the tax system |

| 20. Strengthening of the pension system |

| The 20 Programmes Driving Investment | EUR Billion 2021–2023 | New Green Jobs/1 Million Investment | New Green Jobs Created |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Safe, sustainable and connected mobility strategy | 13.2 | 9.00 | 118,800 |

| 2. Housing rehabilitation and urban renewal programme | 6.82 | 15.20 | 103,664 |

| 6. New Spain 2030 industrial policy and circular economy strategy | 3.78 | 9.90 | 37,422 |

| 9. Development of the national science and innovation system | 3.38 | 8.00 | 27,040 |

| 10. Implementation and integration of renewable energies | 3.16 | 6.95 | 21,962 |

| 13. Preservation of coastal areas and water resources | 2.09 | 8.00 | 16,720 |

| 16. Conservation and restoration of ecosystems and biodiversity | 1.64 | 8.00 | 13,120 |

| 17. Renewable hydrogen roadmap | 1.55 | 5.90 | 9145 |

| 18. Electrical infrastructure, smart networks and storage | 1.36 | 6.35 | 8636 |

| Total Green Initiatives | 36.98 | 356,509 |

| Country | Basic Skills (Content)—Average | Basic Skills (Content) | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reading Comprehension | Active Listening | Writing | Speaking | Mathematics Skills | Science | |||||||

| France | 0.167 | 0.173 | 0.167 | 0.182 | 0.22 | 0.109 | 0.153 | |||||

| Germany | 0.259 | 0.32 | 0.279 | 0.3 | 0.263 | 0.235 | 0.156 | |||||

| Italy | 0.375 | 0.487 | 0.377 | 0.452 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.274 | |||||

| Spain | 0.342 | 0.475 | 0.335 | 0.433 | 0.364 | 0.269 | 0.175 | |||||

| Country | Basic Skills (Process)—Average | Basic Skills (Process) | ||||||||||

| Critical Thinking | Active Learning | Learning Strategies | Monitoring | |||||||||

| France | 0.211 | 0.166 | 0.189 | 0.308 | 0.181 | |||||||

| Germany | 0.228 | 0.255 | 0.268 | 0.223 | 0.165 | |||||||

| Italy | 0.311 | 0.373 | 0.349 | 0.275 | 0.248 | |||||||

| Spain | 0.307 | 0.332 | 0.328 | 0.335 | 0.234 | |||||||

| Country | Social Skills—Average | Social Skills | ||||||||||

| Social Perceptiveness | Coordination | Persuasion | Negotiation | Instructing | Service Orientation | |||||||

| France | 0.158 | 0.152 | 0.19 | 0.1 | 0.129 | 0.259 | 0.116 | |||||

| Germany | 0.228 | 0.225 | 0.117 | 0.341 | 0.293 | 0.219 | 0.175 | |||||

| Italy | 0.19 | 0.209 | 0.138 | 0.222 | 0.208 | 0.28 | 0.082 | |||||

| Spain | 0.187 | 0.197 | 0.166 | 0.177 | 0.169 | 0.28 | 0.133 | |||||

| Country | Technical Skills—Average | Technical Skills | ||||||||||

| Operations Analysis | Technology Design | Equipment Selection | Installation | Programming | Operation Monitoring | Operation and Control | Equipment Maintenance | Troubleshooting | Repairing | Quality Control Analysis | ||

| France | -0.016 | 0.058 | 0.014 | −0.027 | −0.007 | −0.049 | 0.006 | −0.052 | −0.062 | −0.01 | −0.042 | −0.003 |

| Germany | -0.034 | 0.242 | 0.103 | −0.052 | 0.024 | 0.095 | −0.167 | −0.236 | −0.123 | −0.101 | −0.079 | −0.077 |

| Italy | 0.094 | 0.295 | 0.122 | 0.045 | 0.018 | 0.155 | 0.089 | −0.001 | 0.046 | 0.067 | 0.069 | 0.125 |

| Spain | 0.027 | 0.169 | 0.074 | 0.007 | 0.07 | 0.1 | −0.034 | −0.081 | −0.018 | −0.006 | 0.014 | 0.002 |

| Country | Complex Problem Solving Skills—Average | Complex Problem Solving Skills | ||||||||||

| France | 0.094 | 0.094 | ||||||||||

| Germany | 0.244 | 0.244 | ||||||||||

| Italy | 0.341 | 0.341 | ||||||||||

| Spain | 0.256 | 0.256 | ||||||||||

| Country | Resource Management Skills—Average | Resource Management Skills | ||||||||||

| Time Management | Management of Financial Resources | Management of Material Resources | Management of Personnel Resources | |||||||||

| France | 0.169 | 0.17 | 0.124 | 0.144 | 0.238 | |||||||

| Germany | 0.1 | 0.089 | 0.104 | 0.062 | 0.145 | |||||||

| Italy | 0.159 | 0.222 | 0.113 | 0.082 | 0.219 | |||||||

| Spain | 0.093 | 0.191 | 0.028 | 0.031 | 0.124 | |||||||

| Country | Systems Skills | Systems Skills | ||||||||||

| Judgment and Decision Making | Systems Analysis | Systems Evaluation | ||||||||||

| France | 0.133 | 0.143 | 0.118 | 0.139 | ||||||||

| Germany | 0.263 | 0.247 | 0.25 | 0.291 | ||||||||

| Italy | 0.348 | 0.335 | 0.353 | 0.355 | ||||||||

| Spain | 0.302 | 0.299 | 0.306 | 0.302 | ||||||||

| Skill | Skill Above Average |

|---|---|

| Reading Comprehension | − |

| Active Listening | − |

| Writing | − |

| Speaking | − |

| Mathematics Skills | − |

| Science | + |

| Critical Thinking | − |

| Active Learning | − |

| Learning Strategies | − |

| Monitoring | − |

| Social Perceptiveness | − |

| Coordination | − |

| Persuasion | + |

| Negotiation | + |

| Instructing | − |

| Service Orientation | − |

| Complex Problem-Solving | − |

| Operations Analysis | + |

| Technology Design | − |

| Equipment Selection | − |

| Installation | − |

| Programming | − |

| Operation and Control | − |

| Equipment Maintenance | + |

| Troubleshooting | + |

| Repairing | + |

| Judgment and Decision Making | − |

| Systems Analysis | − |

| Systems Evaluation | − |

| Time Management | − |

| Management of financial resources | + |

| Management of material resources | + |

| Management of personnel resources | + |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

García Vaquero, M.; Sánchez-Bayón, A.; Lominchar, J. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies 2021, 14, 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144145

García Vaquero M, Sánchez-Bayón A, Lominchar J. European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies. 2021; 14(14):4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144145

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarcía Vaquero, Martín, Antonio Sánchez-Bayón, and José Lominchar. 2021. "European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain" Energies 14, no. 14: 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144145

APA StyleGarcía Vaquero, M., Sánchez-Bayón, A., & Lominchar, J. (2021). European Green Deal and Recovery Plan: Green Jobs, Skills and Wellbeing Economics in Spain. Energies, 14(14), 4145. https://doi.org/10.3390/en14144145