Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Upcycling

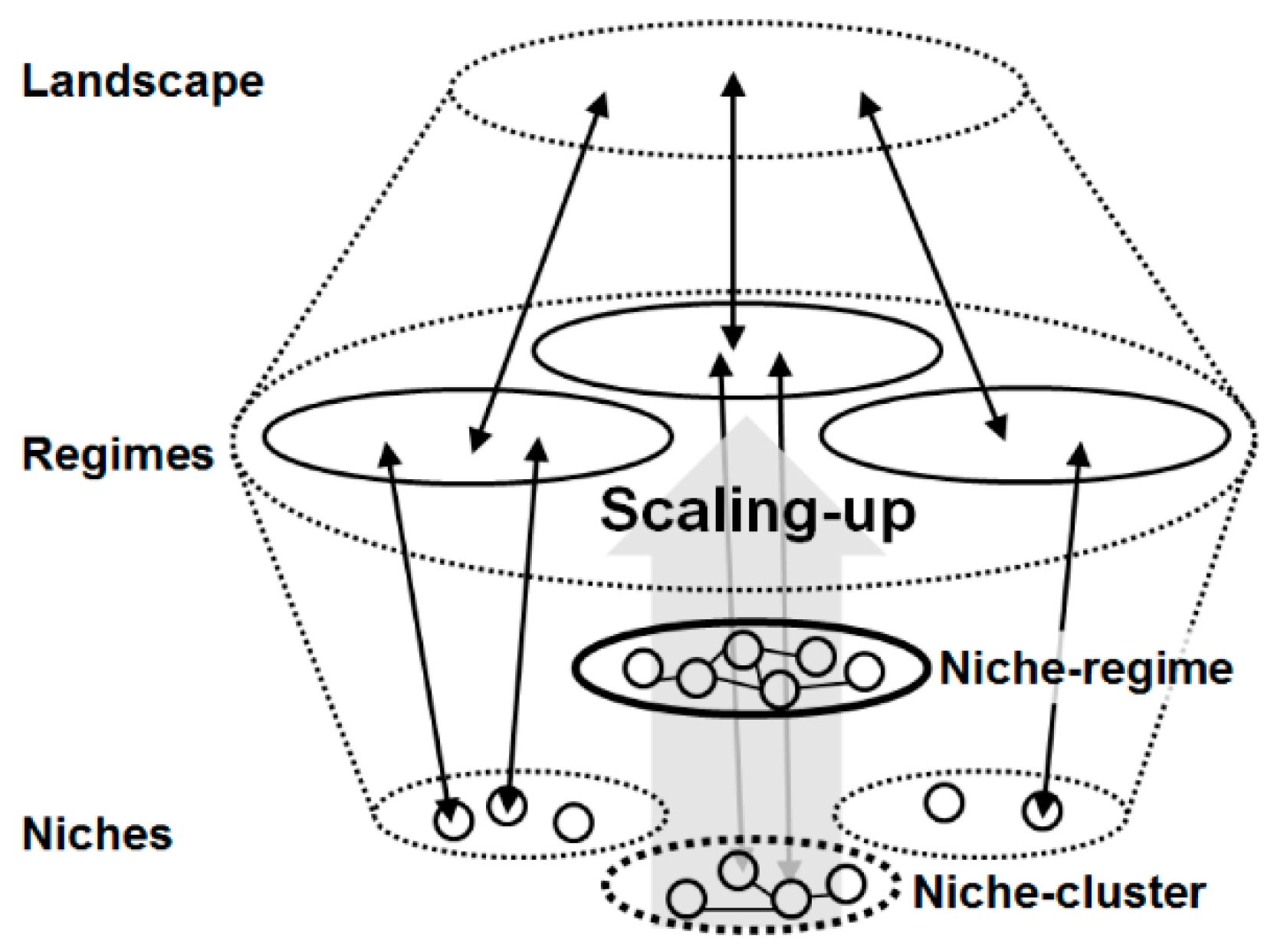

1.2. Scaling Up

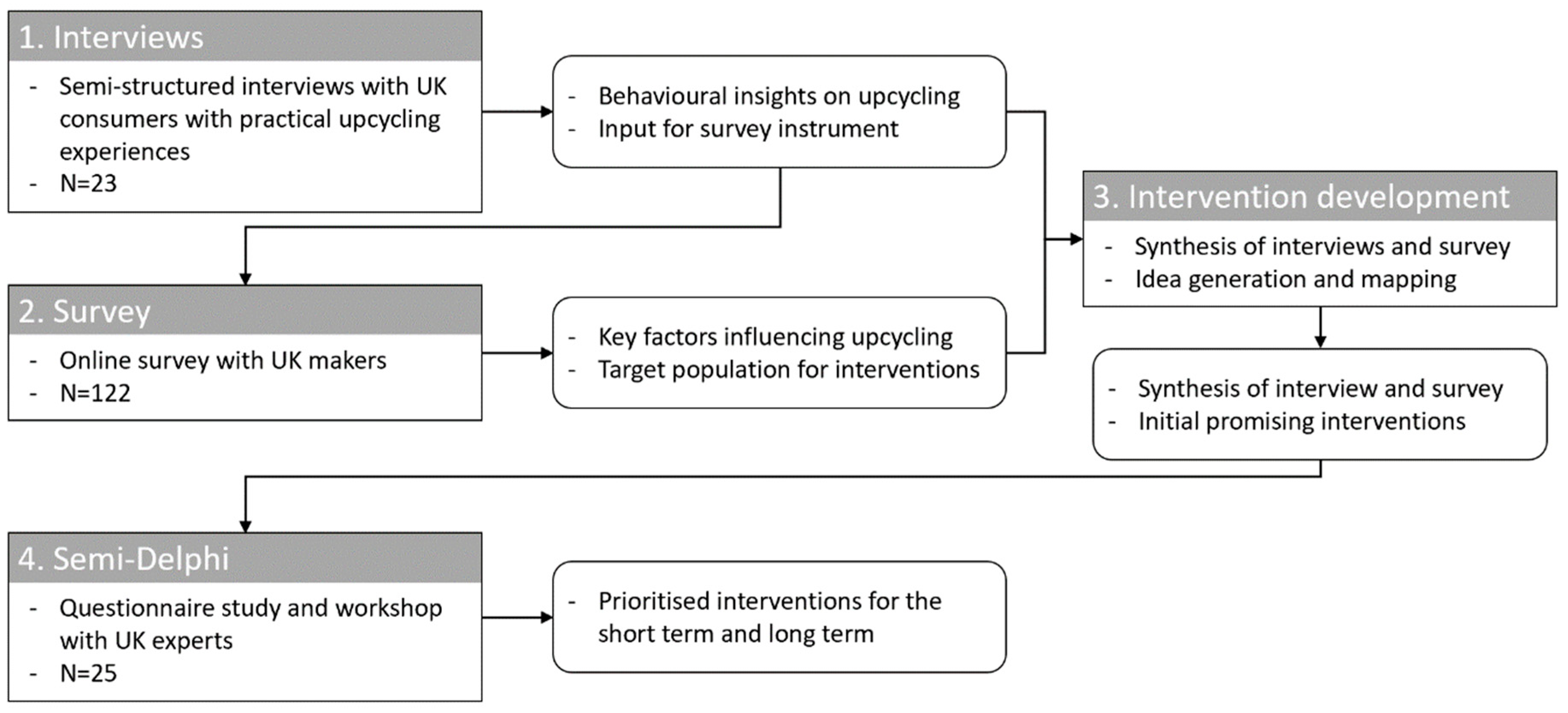

2. Research Methodology

2.1. Interviews

2.1.1. Instrument

2.1.2. Sampling and Participants

2.1.3. Analysis

2.2. Survey

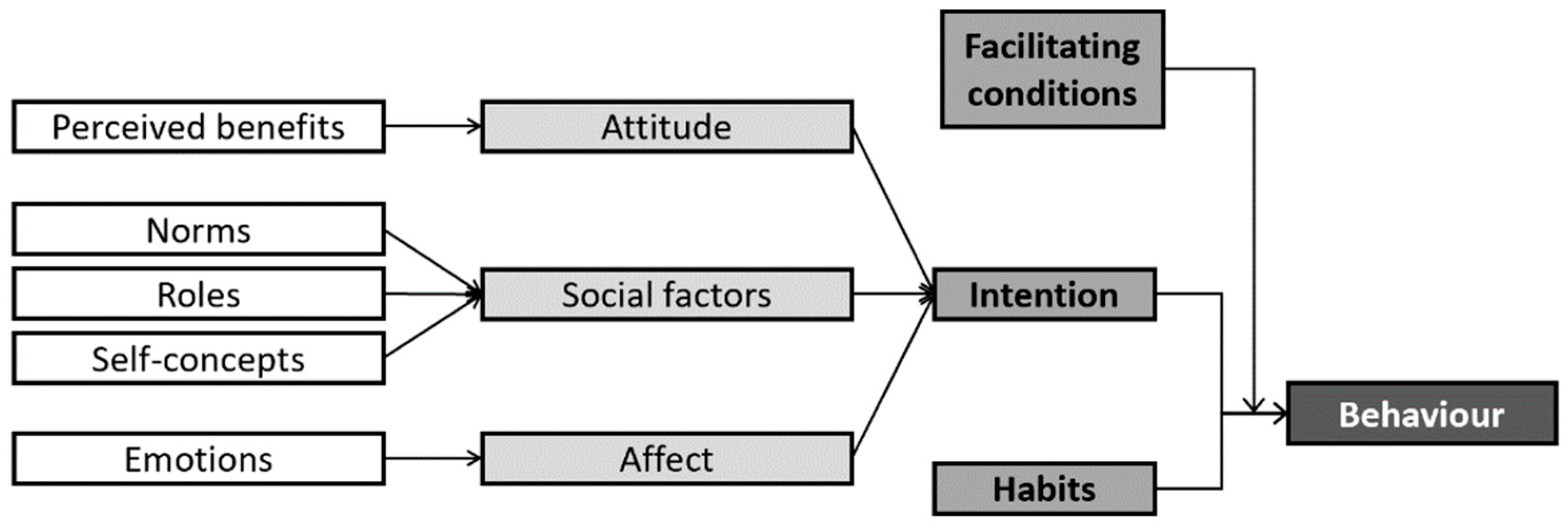

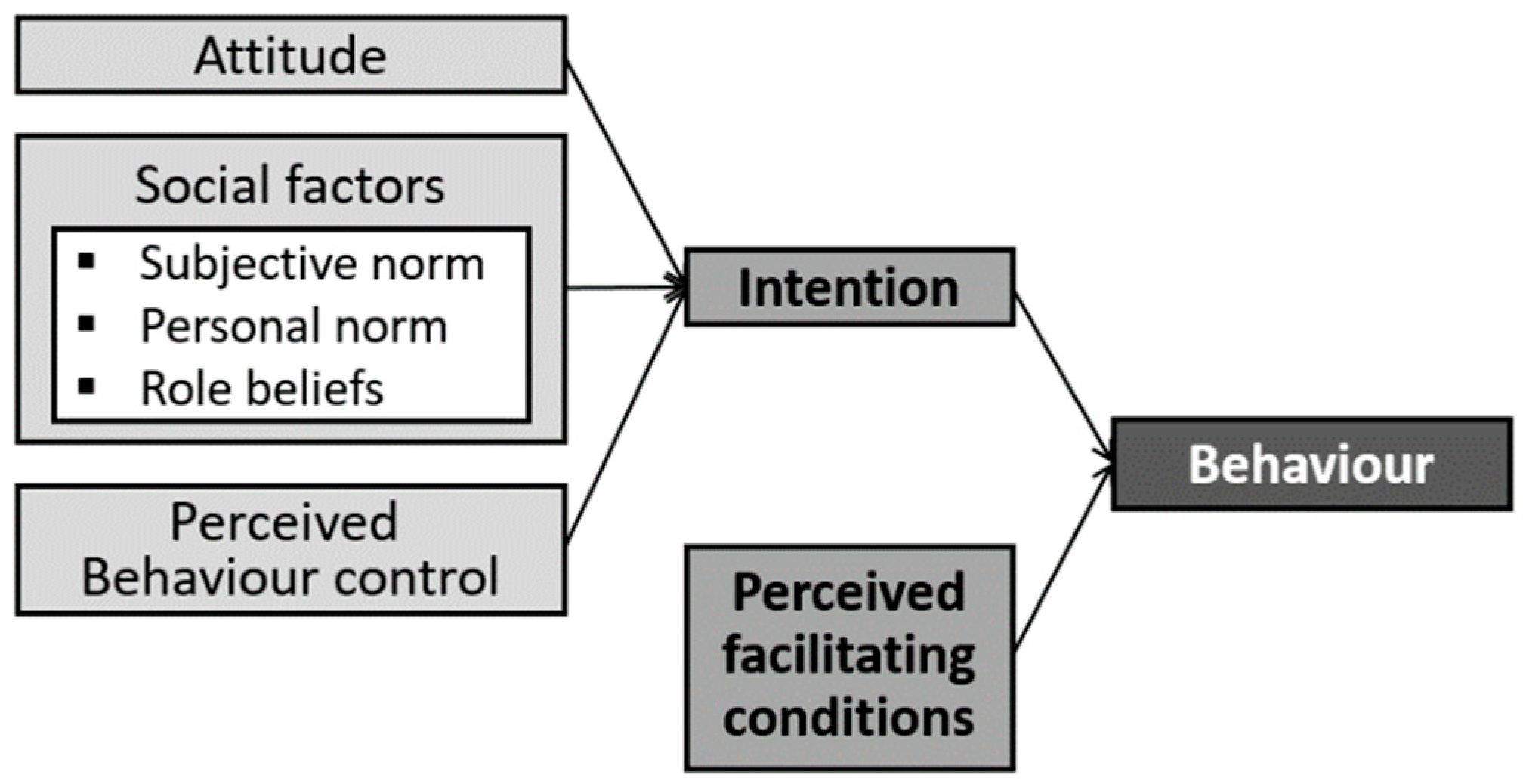

2.2.1. Instrument

2.2.2. Sampling and Respondents

2.2.3. Analysis

2.3. Intervention Development

2.4. Semi-Delphi

2.4.1. Instrument

2.4.2. Sampling and Participants

2.4.3. Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Interviews: Insights into UK Upcycling

3.1.1. Approaches to Upcycling

3.1.2. Context for Upcycling

3.1.3. Factors Influencing Upcycling

3.2. Survey: Key Factors Influencing UK Upcycling

3.2.1. Key Factors Influencing Upcycling

3.2.2. Important Demographic Characteristics

3.3. Intervention Development: Interventions for Scaling Up Upcycling

3.3.1. Synthesis of Interviews and Survey

3.3.2. Interventions

3.4. Semi-Delphi: Prioritised Interventions for Scaling Up Upcycling

3.4.1. Short-Term High Priority Interventions

3.4.2. Short-Term Medium Priority Interventions

3.4.3. Long-Term Priority Interventions

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Interview Questions to Gain Insights into Upcycling

| Category | Sub Category | Questions |

| Approaches to upcycling | Upcycling materials | What kinds of materials do you use for upcycling? |

| Ways of acquiring materials | Where or how do you get the materials? | |

| Material selection criteria | How or why do you choose particular materials? | |

| End product usage | What do you do with the end products after upcycling? | |

| Context for upcycling | When | When do you usually upcycle? |

| How often | How often do you upcycle? | |

| Where | Where do you usually upcycle? | |

| With whom | Do you upcycle by yourself or with others? If with others, who are they? What is the occasion? | |

| Factors influencing upcycling | Perceived benefits | What benefits do you expect and see from upcycling? |

| Norms | Norms are social beliefs that certain behaviours are appropriate, correct or desirable. Are they any social norms involved in your motivation? | |

| Roles | Roles are particular positions in a group, for example, as son or daughter, partner, father or mother, friend, employee, etc. Are there any of your roles involved in your motivation? | |

| Self-concept | Self-concept is your idea of who you are. For example, I am the kind of person who does this. Are there any of your self-concepts involved in your motivation? | |

| Any other motivations | Are there any other motivations for upcycling besides what you have already mentioned? | |

| Emotions | What positive or negative and strong or weak emotions do you feel when upcycling? What emotions do you feel when you complete upcycling? | |

| Habits | What other activities do you habitually engage in, relating to upcycling? Do you have any childhood activities related to upcycling? | |

| Facilitating conditions | Before your first upcycling, what were the barriers? Why were you not upcycling? Have you experienced any problems or difficulties with upcycling? What conditions do you think have facilitated your upcycling so far? |

Appendix B. Fifteen Interventions Used for Testing/Evaluation

- Community workshops: Improve services and facilities of, and access to community workshops with materials, tools, training and space

- Novice toolkits: Design and provide toolkits for notice upcyclers

- Upcycling centre: Operate a reuse/upcycle centre with a product collection service aligned with existing waste collection system

- Materials provision service: Design and provide a service model for improved provision of used materials

- Curriculum enrichment: Enrich the curriculum in art and design at schools, colleges and universities to incorporate advanced upcycling knowledge and skills

- Community events: Organize community-based upcycling events and training sessions

- Competitions: Organize upcycling competitions in schools, universities, communities and industry

- Business consulting: Provide advice and consultancy on upcycling businesses (feasibility and safety test, market identification)

- Communication: Design and provide effective communication materials for the general public and industry

- Campaign: Design and provide a wow experience as an upcycling promotion campaign

- TV and inspirational media: Produce TV shows and other inspirational media to share the best practices

- Incentives for upcycling businesses: Provide tax benefits and subsidies for upcycling-related businesses

- Incentives for upcycling initiatives/research: Provide grants and subsidies for upcycling-related initiatives and research

- Commissioned projects: Demonstrate high quality and value of upcycling through commissioning high profile upcycling projects by famous artists and designers

- Government procurement change: Demonstrate upcycled goods as a new social norm or standard by changing government procurement policy to favour upcycled goods

References

- Barrett, J.; Peters, G.; Wiedmann, T.; Scott, K.; Lenzen, M.; Roelich, K.; Le Quéré, C. Consumption-based GHG emission accounting: A UK case study. Clim. Policy 2013, 13, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millward-Hopkins, J.; Gouldson, A.; Scott, K.; Barrett, J.; Sudmant, A. Uncovering blind spots in urban carbon management: The role of consumption-based carbon accounting in Bristol, UK. Reg. Environ. Chang. 2017, 17, 1467–1478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minx, J.; Baiocchi, G.; Wiedmann, T.; Barrett, J.; Creutzig, F.; Feng, K.; Förster, M.; Pichler, P.; Weisz, H.; Hubacek, K. Carbon footprints of cities and other human settlements in the UK. Environ. Res. Lett. 2013, 8, 035039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggleston, H.S.; Buendia, L.; Miwa, K.; Ngara, T.; Tanabe, K. IPCC guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories; IPCC, 2006; Available online: https://www.ipcc-nggip.iges.or.jp/public/2006gl/index.html (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Wiedmann, T.; Wood, R.; Lenzen, M.; Minx, J.C. Development of an Embedded Carbon Emissions Indicator-Producing a Time Series of Input-Output Tables und Embedded Carbon Dioxide Emissions for the UK by Using a MRIO Data Optimisation System; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2008; Available online: https://opus4.kobv.de/opus4-hsog/frontdoor/index/index/docId/1918 (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Wiedmann, T.; Wood, R.; Minx, J.C.; Lenzen, M.; Guan, D.; Harris, R. A carbon footprint time series of the UK–results from a multi-region input–output model. Econ. Syst. Res. 2010, 22, 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medlock, K.B., III; Soligo, R. Economic development and end-use energy demand. Energy J. 2001, 22, 77–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorrell, S. Reducing energy demand: A review of issues, challenges and approaches. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 47, 74–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UK Government 2010 to 2015 Government Policy: Greenhouse Gas Emissions. Available online: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/2010-to-2015-government-policy-greenhouse-gas-emissions/2010-to-2015-government-policy-greenhouse-gas-emissions#issue (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- What is EUED? Available online: http://www.eued.ac.uk/whatiseued (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- About CIE-MAP. Available online: http://ciemap.leeds.ac.uk/index.php/about/ (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Van den Bosch, S.J.M. Transition experiments: Exploring societal changes towards sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Gutowski, T.G.; Worrell, E. Material efficiency: Providing material services with less material production. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A 2013, 371, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Factors Influencing Upcycling for UK Makers. Sustainability 2019, 11, 870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K. Sustainable Production and Consumption by Upcycling: Understanding and Scaling Up Niche Environmentally Significant Behaviour. Ph.D. Thesis, Nottingham Trent University, Nottingham, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Genovese, A.; Acquaye, A.A.; Figueroa, A.; Koh, S.L. Sustainable supply chain management and the transition towards a circular economy: Evidence and some applications. Omega 2017, 66, 344–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emgin, B. Trashion: The Return of the Disposed. Design Issues 2012, 28, 63–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braungart, M.; McDonough, W. Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way We Make Things; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, M.; Eklund, M. Improving the environmental performance of biofuels with industrial symbiosis. Biomass Bioenergy 2011, 35, 1747–1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McDonough, W.; Braungart, M. The Upcycle: Beyond Sustainability—Designing for Abundance; North Point Press: New York, NY, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Individual Upcycling Practice: Exploring the Possible Determinants of Upcycling Based on a Literature Review. In Proceedings of the Sustainable Innovation 2014 Conference, Copenhagen, Denmark, 3–4 November 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Emerging Social Movements for Sustainability: Understanding and Scaling Up Upcycling in the UK. In The Palgrave Handbook of Sustainability; Brinkmann, R., Garren, S., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 299–312. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M.; Cullen, J.M.; Carruth, M.A.; Cooper, D.R.; McBrien, M.; Milford, R.L.; Moynihan, M.C.; Patel, A.C. Sustainable Materials: With Both Eyes Open; UIT Cambridge Ltd: Cambridge, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Maestri, L.; Wakkary, R. Understanding repair as a creative process of everyday design. In Proceedings of the 8th ACM Conference on Creativity and Cognition, Atlanta, GA, USA, 3–6 November 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.; Paulos, E. Practices in the creative reuse of e-waste. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 7–12 May 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Guide, V.D.R., Jr.; Jayaraman, V.; Linton, J.D. Building contingency planning for closed-loop supply chains with product recovery. J. Oper. Manag. 2003, 21, 259–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, S.S.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C.S.; Shih, K. Value-added recycling of construction waste wood into noise and thermal insulating cement-bonded particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2016, 125, 316–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhir, R.; Paine, K.; Dyer, T.; Tang, A. Value-added recycling of domestic, industrial and construction arisings as concrete aggregate. Concr. Eng. 2004, 8, 43–48. [Google Scholar]

- Stahel, W.R. The circular economy. Nature 2016, 531, 435–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Circular Economy. Available online: http://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org (accessed on 14 June 2019).

- Geissdoerfer, M.; Savaget, P.; Bocken, N.M.; Hultink, E.J. The Circular Economy–A new sustainability paradigm? J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 143, 757–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, T. (Ed.) Longer Lasting Products; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Allwood, J.M.; Ashby, M.F.; Gutowski, T.G.; Worrell, E. Material efficiency: A white paper. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2011, 55, 362–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cramer, J.M. Pros and Cons of Optimising the Life of Consumer Electronics Products. In Proceedings of the First International Working Seminar on Reuse, Edinburgh, UK, 11–13 November 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, T. The durability of consumer durables. Bus. Strategy Environ. 1994, 3, 23–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brezet, H.; Van Hemel, C.; Böttcher, H.; Clarke, R. Ecodesign: A Promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Consumption; UNEP: Nairobi, Kenya, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Bramston, D.; Maycroft, N. Designing with waste. In Materials Experience: Fundamentals of Materials and Design; Karana, E., Pedgley, O., Rognoli, V., Eds.; Butterworth-Heinemann: Oxford, UK, 2013; pp. 123–133. [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo, C.; Levendis, Y.A. Upcycling waste plastics into carbon nanomaterials: A review. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2014, 131, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.L.; Chan, P.Y.; Venkatraman, P.; Apeagyei, P.; Cassidy, T.; Tyler, D.J. Standard vs. Upcycled Fashion Design and Production. Fash. Pract. 2016, 9, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T. Sarah Turner–Eco-artist and designer through craft-based upcycling. Craft Res. 2015, 6, 113–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teli, M.; Valia, S.P.; Maurya, S.; Shitole, P. Sustainability Based Upcycling and Value Addition of Textile Apparels. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Multidisciplinary Innovation for Sustainability and Growth, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 27–28 August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Cumming, D. A Case Study Engaging Design for Textile Upcycling. J. Text. Des. Res. Pract. 2017, 4, 113–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmsköld, A. Reusing Textiles: On Material and Cultural Wear and Tear. Cult. Unbound J. Curr. Cult. Res. 2015, 7, 31–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, E. To Have or to Be? Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Rathje, W.L.; Murphy, C. Rubbish: The archaeology of garbage; University of Arizona Press: Tucson, AZ, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins, G. Plastic bags: Living with rubbish. Int. J. Cult. Stud. 2001, 4, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packard, V. The Waste Makers; Penguin Books: Harmondsworth, Australia, 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Salvia, G.; Cooper, T.; Fisher, T.; Harmer, L.; Barr, C. What is broken? Expected lifetime, perception of brokenness and attitude towards maintenance and repair. In Proceedings of the Product Lifetimes and the Environment (PLATE) Conference, Nottingham, UK, 17–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Van Nes, N. Understanding replacement behaviour and exploring design solutions. In Longer Lasting Products: Alternatives to the Throwaway Society; Cooper, T., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2010; pp. 107–132. [Google Scholar]

- Farrant, L.; Olsen, S.I.; Wangel, A. Environmental benefits from reusing clothes. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2010, 15, 726–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, C. Makers: The New Industrial Revolution; Random House Business: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Charter, M.; Keiller, S. Grassroots Innovation and the Circular Economy: A Global Survey of Repair Cafés and Hackerspaces; The Centre for Sustainable Design: Farnham, UK, 2014; Available online: https://research.uca.ac.uk/2722/1/Survey-of-Repair-Cafes-and-Hackerspaces.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Sung, K. A review on upcycling: Current body of literature, knowledge gaps and a way forward. In Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Environmental, Cultural, Economic and Social Sustainability, Venice, Italy, 13–14 April 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pol, V.G. Upcycling: Converting waste plastics into paramagnetic, conducting, solid, pure carbon microspheres. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 4753–4759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mo, Y.; Zhao, L.; Chen, C.; Tan, G.Y.A.; Wang, J. Comparative pyrolysis upcycling of polystyrene waste: Thermodynamics, kinetics, and product evolution profile. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2013, 111, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.H.; Kim, S.H. Poly (ethylene terephthalate) recycling for high value added textiles. Fash. Text. 2014, 1, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fletcher, K. Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys; Earthscan: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J.H.; Kim, Y.H. A Study on fashion design for up-cycled waste resources. J. Korean Soc. Costume 2014, 64, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Tyler, D.; Apeagyei, P. Upcycling as a design strategy for product lifetime optimisation and societal change. In Proceedings of the Product Lifetimes and the Environment (PLATE) Conference, Nottingham, UK, 17–19 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsworthy, K. Design for Cyclability: Pro-active approaches for maximising material recovery. Mak. Futures 2014, 3, 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Santulli, C.; Langella, C. ‘+ design-waste’: A project for upcycling refuse using design tools. Int. J. Sustain. Des. 2013, 2, 105–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janigo, K.A.; Wu, J. Collaborative Redesign of Used Clothes as a Sustainable Fashion Solution and Potential Business Opportunity. Fash. Pract. 2015, 7, 75–97. [Google Scholar]

- Todeschini, B.V.; Cortimiglia, M.N.; Callegaro-de-Menezes, D.; Ghezzi, A. Innovative and sustainable business models in the fashion industry: Entrepreneurial drivers, opportunities, and challenges. Bus. Horiz. 2017, 60, 759–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Ramanathan, U.; Singh, J. Challenges and support for scaling up upcycling businesses in the UK: Insights from small-business entrepreneurs. In Proceedings of the Product Lifetimes and the Environment (PLATE) Conference, Delft, The Netherlands, 8–10 November 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Steinhilper, R.; Hieber, M. Remanufacturing-the key solution for transforming “downcycling” into “upcycling” of electronics. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Symposium on Electronics and the Environment, Denver, CO, USA, 9 May 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Busch, O.V. Fashion-able. Hacktivism and engaged fashion design. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Park, H.H. The Influence of LOHAS Consumption Tendency and Perceived Consumer Effectiveness on Trust and Purchase Intention Regarding Upcycling Fashion Goods. Int. J. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 16, 37–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twigger Holroyd, A. Fashion Diggers: Transgressive making for personal benefit. Mak. Futures 2012, 2, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy, D.; Han, S. Upcycling fashion for mass production. In Sustainability in Fashion and Textiles: Values, Design, Production and Consumption; Gardetti, M., Torres, A., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2013; pp. 148–163. [Google Scholar]

- La Mantia, F.P. Polymer mechanical recycling: Downcycling or upcycling? Prog. Rubber Plast. Recycl. Technol. 2004, 20, 11–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Iris, K.M.; Tsang, D.C.; Yu, K.; Li, S.; Poon, C.S.; Dai, J. Upcycling wood waste into fibre-reinforced magnesium phosphate cement particleboards. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 159, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hossain, M.U.; Wang, L.; Iris, K.M.; Tsang, D.C.; Poon, C. Environmental and technical feasibility study of upcycling wood waste into cement-bonded particleboard. Constr. Build. Mater. 2018, 173, 474–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennacchia, E.; Tiberi, M.; Carbonara, E.; Astiaso Garcia, D.; Cumo, F. Reuse and upcycling of municipal waste for zeb envelope design in European urban areas. Sustainability 2016, 8, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, M. When creative consumers go green: Understanding consumer upcycling. J. Prod. Brand Manag. 2016, 25, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Haan, J.H.; Rotmans, J. Patterns in transitions: Understanding complex chains of change. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 2011, 78, 90–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A. Translating sustainabilities between green niches and socio-technical regimes. Technol. Anal. Strateg. Manag. 2007, 19, 427–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rip, A.; Kemp, R. Technological change. In Human Choice and Climate Change; Rayner, S., Malone, E., Eds.; Battelle Press: Columbus, OH, USA, 1998; Volume 2, pp. 327–399. [Google Scholar]

- Geels, F.W. Technological transitions as evolutionary reconfiguration processes: A multi-level perspective and a case-study. Res. Policy 2002, 31, 1257–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceschin, F. The Introduction and Scaling Up of Sustainable Product-Service Systems. A New Role for Strategic Design for Sustainability. Ph.D. Thesis, The Polytechnic University of Milan, Milan, Italy, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Haxeltine, A.; Whitmarsh, L.; Bergman, N.; Rotmans, J.; Schilperoord, M.; Kohler, J. A Conceptual Framework for transition modelling. Int. J. Innov. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 3, 93–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darnton, A.; Verplanken, B.; White, P.; Whitmarsh, L. Habits, Routines and Sustainable Lifestyles; Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, R.B.; Onwuegbuzie, A.J. Mixed methods research: A research paradigm whose time has come. Educ. Res. 2004, 33, 14–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziglio, E. The Delphi Method and Its Contribution to Decision-Making; Edler, M., Ziglio, E., Eds.; Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health; Jessica Kingsley Publishers: London, UK, 1996; pp. 3–33. [Google Scholar]

- Barriball, K.L.; While, A. Collecting Data using a semi-structured interview: A discussion paper. J. Adv. Nurs. 1994, 19, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triandis, H.C. Interpersonal Behavior; Brooks/Cole: Monterey, CA, USA, 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Nesta Top Findings from the Open Dataset of UK Makerspaces. Available online: http://www.nesta.org.uk/blog/top-findings-open-dataset-uk-makerspaces?utm_source=Nesta+Weekly+Newsletter&utm_campaign=dea994abb8-Nesta_newsletter_29_04_154_28_2015&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_d17364114d-dea994abb8-180827681 (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- UK Hackspace Foundation. Available online: http://www.hackspace.org.uk/view/Main_Page (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Goodman, L.A. Snowball sampling. Ann. Math. Stat. 1961, 32, 148–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fishbein, M.; Ajzen, I. Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research; Addison-Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. Constructing a TPB questionnaire: Conceptual and methodological considerations. 2002. Available online: https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/0574/b20bd58130dd5a961f1a2db10fd1fcbae95d.pdf?_ga=2.217297366.1799960242.1563460349-1419732309.1563460349 (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Bamberg, S.; Schmidt, P. Incentives, morality, or habit? Predicting students’ car use for university routes with the models of Ajzen, Schwartz, and Triandis. Environ. Behav. 2003, 35, 264–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagnon, M.; Godin, G.; Gagné, C.; Fortin, J.; Lamothe, L.; Reinharz, D.; Cloutier, A. An adaptation of the theory of interpersonal behaviour to the study of telemedicine adoption by physicians. Int. J. Med. Inf. 2003, 71, 103–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francis, J.J.; Eccles, M.P.; Johnston, M.; Walker, A.; Grimshaw, J.; Foy, R.; Kaner, E.F.; Smith, L.; Bonetti, D. Constructing questionnaires based on the theory of planned behaviour. Man. Health Serv. Res. 2004, 2010, 2–12. [Google Scholar]

- Tonglet, M.; Phillips, P.S.; Read, A.D. Using the Theory of Planned Behaviour to investigate the determinants of recycling behaviour: A case study from Brixworth, UK. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2004, 41, 191–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryman, A. Social Research Methods; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Robson, C. Real World Research: A Resource for Social Scientists and Practitioner-Researchers; John Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Toombs, A.; Bardzell, S.; Bardzell, J. Becoming makers: Hackerspace member habits, values, and identities. J. Peer Prod. 2014, 5, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Buxmann, P.; Hinz, O. Makers. Bus. Inf. Syst. Eng. 2013, 5, 357–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolko, J. Abductive thinking and sensemaking: The drivers of design synthesis. Des. Issues 2010, 26, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolko, J. Information architecture and design strategy: The importance of synthesis during the process of design. In Proceedings of the Industrial Designers Society of America Conference; 2007. Available online: http://www.jonkolko.com/writingInfoArchDesignStrategy.php (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Defra. A Framework for Pro-Environmental Behaviours; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Defra. The Sustainable Lifestyles Framework; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Michie, S.; van Stralen, M.M.; West, R. The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implement Sci. 2011, 6, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eppel, S.; Sharp, V.; Davies, L. A review of Defra’s approach to building an evidence base for influencing sustainable behaviour. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2013, 79, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collier, A.; Cotterill, A.; Everett, T.; Muckle, R.; Pike, T.; Vanstone, A. Understanding and influencing behaviours: A Review of Social Research, Economics and Policy Making in Defra; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs: London, UK, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Adler, M.; Ziglio, E. Gazing into the Oracle: The Delphi Method and Its Application to Social Policy and Public Health; Jessica Kingsley: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Individual Upcycling in the UK: Insights for Scaling up Towards Sustainable Development. In Sustainable Development Research at Universities in the United Kingdom; Leal Filho, W., Ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 193–227. [Google Scholar]

- Blom, J. Personalization: A taxonomy. In Proceedings of the CHI EA ’00, Hague, The Netherlands, 1–6 April 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Mugge, R.; Schoormans, J.P.L.; Schifferstein, H.N.J. Emotional bonding with personalised products. J. Eng. Des. 2009, 20, 467–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoltzfus, J.C. Logistic regression: A brief primer. Acad. Emerg. Med. 2011, 18, 1099–1104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greening, L.A.; Greene, D.L.; Difiglio, C. Energy efficiency and consumption—The rebound effect—A survey. Energy Policy 2000, 28, 389–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hobolt, S.B. The Brexit vote: A divided nation, a divided continent. J. Eur. Public Policy 2016, 23, 1259–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watt, J.; Austin, M.J.; Simocko, C.K.; Pete, D.V.; Chavez, J.; Ammerman, L.M.; Huber, D.L. Formation of Metal Nanoparticles Directly from Bulk Sources Using Ultrasound and Application to E-Waste Upcycling. Small 2018, 14, 1703615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hjelmgren, D.; Salomonson, N.; Ekström, K.M. Upcycling of Pre-Consumer Waste. In Waste Management and Sustainable Consumption; Ekström, K., Ed.; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2015; pp. 187–198. [Google Scholar]

- Bridgens, B.; Powell, M.; Farmer, G.; Walsh, C.; Reed, E.; Royapoor, M.; Gosling, P.; Hall, J.; Heidrich, O. Creative upcycling: Reconnecting people, materials and place through making. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 189, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, I.; Shaw, P. Reuse: Fashion or future? Waste Manag. 2017, 60, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albinsson, P.A.; Yasanthi Perera, B. Alternative marketplaces in the 21st century: Building community through sharing events. J. Consum. Behav. 2012, 11, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGinley, T. JunkUp: Supporting e-procurement of used materials in the construction industry using eBay and BIM. In Proceedings of the Unmaking Waste 2015 Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 22–24 May 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Kant Hvass, K. Post-retail responsibility of garments–a fashion industry perspective. J. Fash. Mark. Manag. 2014, 18, 413–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WilliAms, A. Fashionable dilemmas. Crit. Stud. Fash. Beauty 2011, 2, 69–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dissanayake, G.; Sinha, P. An examination of the product development process for fashion remanufacturing. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 104, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binotto, C.; Payne, A. The poetics of waste: Contemporary fashion practice in the context of wastefulness. Fash. Pract. 2017, 9, 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watson, M.; Shove, E. Product, competence, project and practice: DIY and the dynamics of craft consumption. J. Consum. Cult. 2008, 8, 69–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willett, R. Making, makers, and makerspaces: A discourse analysis of professional journal articles and blog posts about makerspaces in public libraries. Libr. Q. 2016, 86, 313–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratich, J. The digital touch: Craft-work as immaterial labour and ontological accumulation. Ephemer. Theory Politics Organ. 2010, 10, 303–318. [Google Scholar]

- Luckman, S.; Andrew, J. Online Selling and the Growth of Home-Based Craft Micro-enterprise: The ‘New Normal’ of Women’s Self-(under) Employment. In The New Normal of Working Lives; Taylor, S., Luckman, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 19–39. [Google Scholar]

- Mason, R. The meaning and value of home-based craft. Int. J. Art Des. Educ. 2005, 24, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, J. Here’s one I made earlier: Making and living with home craft in contemporary Britain. J. Des. Hist. 2004, 17, 267–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheatle, A.; Jackson, S.J. Digital entanglements: Craft, computation and collaboration in fine art furniture production. In Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 14–18 March 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Phetteplace, E.; Dixon, N.; Ward, M. The maker movement and the Louisville free public library. Ref. User Serv. Q. 2014, 54, 17–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Gauntlett, D. Making is Connecting; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, T. Motivating Sustainable Consumption: A Review of Evidence on Consumer Behaviour and Behavioural Change; University of Surrey: Surrey, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bernstad, A. Household food waste separation behavior and the importance of convenience. Waste Manag. 2014, 34, 1317–1323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sustainable Consumption Roundtable. I Will If You Will: Towards Sustainable Consumption; Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs and Department of Trade and Industry: London, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Carrington, M.J.; Neville, B.A.; Whitwell, G.J. Why ethical consumers don’t walk their talk: Towards a framework for understanding the gap between the ethical purchase intentions and actual buying behaviour of ethically minded consumers. J. Bus. Ethics 2010, 97, 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, L.M.; Shiu, E.; Shaw, D. Who says there is an intention–behaviour gap? Assessing the empirical evidence of an intention–behaviour gap in ethical consumption. J. Bus. Ethics 2016, 136, 219–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juvan, E.; Dolnicar, S. The attitude–behaviour gap in sustainable tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 2014, 48, 76–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulstridge, E.; Carrigan, M. Do consumers really care about corporate responsibility? Highlighting the attitude—Behaviour gap. J. Commun. Manag. 2000, 4, 355–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Hwang, K.; McDonald, S.; Oates, C.J. Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 18, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vermeir, I.; Verbeke, W. Sustainable food consumption among young adults in Belgium: Theory of planned behaviour and the role of confidence and values. Ecol. Econ. 2008, 64, 542–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.H.; Hancer, M. The role of attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, and moral norm in the intention to purchase local food products. J. Foodserv. Bus. Res. 2016, 19, 338–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Ha, S. Understanding consumer recycling behavior: Combining the theory of planned behavior and the norm activation model. Fam. Consum. Sci. Res. J. 2014, 42, 278–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, K. Mass communication and pro-environmental behaviour: Waste recycling in Hong Kong. J. Environ. Manag. 1998, 52, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, C. ‘Home is where the art is’: Women, handicrafts and home improvements 1750–1900. J. Des. Hist. 2006, 19, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, P. Do it yourself: Democracy and design. J. Des. Hist. 2006, 19, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakefield, M.A.; Loken, B.; Hornik, R.C. Use of mass media campaigns to change health behaviour. Lancet 2010, 376, 1261–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SØGAARD, A.J.; FØNNEBØ, V. Self-reported change in health behaviour after a mass media-based health education campaign. Scand. J. Psychol. 1992, 33, 125–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heath, G.W.; Parra, D.C.; Sarmiento, O.L.; Andersen, L.B.; Owen, N.; Goenka, S.; Montes, F.; Brownson, R.C. Lancet Physical Activity Series Working Group Evidence-based intervention in physical activity: Lessons from around the world. Lancet 2012, 380, 272–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swanton, R.; Allom, V.; Mullan, B. A meta-analysis of the effect of new-media interventions on sexual-health behaviours. Sex Transm Infect 2015, 91, 14–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.L.; Owen, N.; Bauman, A.E. Mediated approaches for influencing physical activity: Update of the evidence on mass media, print, telephone and website delivery of interventions. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2004, 7, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brendryen, H.; Kraft, P. Happy Ending: A randomized controlled trial of a digital multi-media smoking cessation intervention. Addiction 2008, 103, 478–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hargreaves, T. Practice-ing behaviour change: Applying social practice theory to pro-environmental behaviour change. J. Consum. Cult. 2011, 11, 79–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shove, E.; Pantzar, M.; Watson, M. The Dynamics of Social Practice: Everyday Life and How it Changes; Sage: London, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Spurling, N.J.; McMeekin, A.; Southerton, D.; Shove, E.A.; Welch, D. Interventions in Practice: Reframing Policy Approaches to Consumer Behavior; Lancaster University: Lancaster, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- The World’s First Recycling Mall Is Found in Eskilstuna. Available online: https://www.retuna.se/sidor/in-english/ (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- Seoul Upcycling Plaza. Available online: http://www.seoulup.or.kr/eng/index.do (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- Wijayanti, D.R.; Suryani, S. Waste bank as community-based environmental governance: A lesson learned from Surabaya. Procedia-Soc. Behav. Sci. 2015, 184, 171–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothwell, R. Technology-based small firms and regional innovation potential: The role of public procurement. J. Public Policy 1984, 4, 307–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geroski, P.A. Procurement policy as a tool of industrial policy. Int. Rev. Appl. Econ. 1990, 4, 182–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aschhoff, B.; Sofka, W. Innovation on demand—Can public procurement drive market success of innovations? Res. Policy 2009, 38, 1235–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biran, A.; Schmidt, W.; Varadharajan, K.S.; Rajaraman, D.; Kumar, R.; Greenland, K.; Gopalan, B.; Aunger, R.; Curtis, V. Effect of a behaviour-change intervention on handwashing with soap in India (SuperAmma): A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Glob. Health 2014, 2, 145–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rissel, C.E.; New, C.; Wen, L.M.; Merom, D.; Bauman, A.E.; Garrard, J. The effectiveness of community-based cycling promotion: Findings from the Cycling Connecting Communities project in Sydney, Australia. Int. J. Behav. Nutr. Phys. Act. 2010, 7, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, B.E.; Schmidt, W.P.; Aunger, R.; Garbrah-Aidoo, N.; Animashaun, R. Marketing hygiene behaviours: The impact of different communication channels on reported handwashing behaviour of women in Ghana. Health Educ. Res. 2007, 23, 392–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steg, L.; Vlek, C. Encouraging pro-environmental behaviour: An integrative review and research agenda. J. Environ. Psychol. 2009, 29, 309–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berge, L.I.O.; Bjorvatn, K.; Tungodden, B. Human and financial capital for microenterprise development: Evidence from a field and lab experiment. Manag. Sci. 2014, 61, 707–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.S.; Osteryoung, J.S. A comparison of critical success factors for effective operations of university business incubators in the United States and Korea. J. Small Bus. Manag. 2004, 42, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.; Chen, Y.J. Impact of government financial intervention on competition among green supply chains. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2012, 138, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peidong, Z.; Yanli, Y.; Yonghong, Z.; Lisheng, W.; Xinrong, L. Opportunities and challenges for renewable energy policy in China. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2009, 13, 439–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Luo, C. Overall review of renewable energy subsidy policies in China–Contradictions of intentions and effects. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 41, 1478–1488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waste Not Want Not: Sweden to Give Tax Breaks for Repairs. Available online: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/sep/19/waste-not-want-not-sweden-tax-breaks-repairs (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- Bozeman, B.; Gaughan, M. Impacts of grants and contracts on academic researchers’ interactions with industry. Res. Policy 2007, 36, 694–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godin, B. The impact of research grants on the productivity and quality of scientific research; INRS: Ottawa, IL, USA, 2003; Available online: http://www.csiic.ca/PDF/NSERC.pdf (accessed on 18 July 2019).

- Ton, G.; Klerkx, L.; de Grip, K.; Rau, M. Innovation grants to smallholder farmers: Revisiting the key assumptions in the impact pathways. Food Policy 2015, 51, 9–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Digelidis, N.; Papaioannou, A.; Laparidis, K.; Christodoulidis, T. A one-year intervention in 7th grade physical education classes aiming to change motivational climate and attitudes towards exercise. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 2003, 4, 195–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michie, S.; Abraham, C. Interventions to change health behaviours: Evidence-based or evidence-inspired? Psychol. Health 2004, 19, 29–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, M.; Burns, C.F.; McGuinness, M.; Heslin, J.; Murphy, N.M. Influence of a health education intervention on physical activity and screen time in primary school children: ‘Switch Off–Get Active’. J. Sci. Med. Sport 2006, 9, 388–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nutbeam, D. Health literacy as a public health goal: A challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot. Int. 2000, 15, 259–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodwin, M.J.; Greasley, S.; John, P.; Richardson, L. Can we make environmental citizens? A randomised control trial of the effects of a school-based intervention on the attitudes and knowledge of young people. Environ. Politics 2010, 19, 392–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyes, E.; Stanisstreet, M. Environmental education for behaviour change: Which actions should be targeted? Int. J. Sci. Educ. 2012, 34, 1591–1614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boudet, H.; Ardoin, N.M.; Flora, J.; Armel, K.C.; Desai, M.; Robinson, T.N. Effects of a behaviour change intervention for Girl Scouts on child and parent energy-saving behaviours. Nat. Energy 2016, 1, 16091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, W.; Davis, M.; McNeill, I.M.; Malhotra, B.; Russell, S.; Unsworth, K.; Clegg, C.W. Changing behaviour: Successful environmental programmes in the workplace. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2015, 24, 689–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dewulf, A.E.; Termeer, C.J.; Werkman, R.A.; Breeman, G.R.; Poppe, K.J. Transition management for sustainability: Towards a multiple theory approach. In Transitions towards Sustainable Agriculture and Food Chains in Peri-Urban Areas; Poppe, K., Termeer, C., Slingerland, M., Eds.; Wageningen Academic: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 25–50. [Google Scholar]

- Shove, E.; Walker, G. Governing transitions in the sustainability of everyday life. Res. Policy 2010, 39, 471–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vinnari, M.; Vinnari, E. A framework for sustainability transition: The case of plant-based diets. J. Agric. Environ. Ethics 2014, 27, 369–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raven, R. Niche accumulation and hybridisation strategies in transition processes towards a sustainable energy system: An assessment of differences and pitfalls. Energy Policy 2007, 35, 2390–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vezzoli, C.; Ceschin, F.; Kemp, R. Designing transition paths for the diffusion of sustainable system innovations. A new potential role for design in transition management? In Proceedings of the Changing the Change: Design, Visions, Proposals and Tools, Turin, Italy, 10–12 July 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Foxon, T.J.; Reed, M.S.; Stringer, L.C. Governing long-term social–ecological change: What can the adaptive management and transition management approaches learn from each other? Environ. Policy Gov. 2009, 19, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liesbet, H.; Gary, M. Unraveling the central state, but how? Types of multi-level governance. Am. Political Sci. Rev. 2003, 97, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Schoor, T.; Scholtens, B. Power to the people: Local community initiatives and the transition to sustainable energy. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2015, 43, 666–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upcycled Hour. Available online: https://www.upcycledhour.co.uk/ (accessed on 18 June 2019).

- Chertow, M.R. Industrial symbiosis: Literature and taxonomy. Annu. Rev. Energy Environ. 2000, 25, 313–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Instruction |

|---|---|

| 01 | Review all interventions. |

| 02 | Make comments on any intervention. |

| 03 | Rate the level of importance and feasibility of each intervention

|

| 04 | Vote for the most suitable actor(s) for each intervention (amongst government, local authorities, companies, NGOs (non-governmental organisations), designers, others—specify) |

| Category | Main Findings | Implications for Scaling Up |

|---|---|---|

| Approaches to upcycling | Frequently used materials identified | Target wood, furniture, metal, electronics, fabric and packaging as mainly used materials provision |

| Frequently used source of materials identified as online | Provide online service (for searching and purchasing) for improved materials provision | |

| Major material selection criteria identified | Provide estimated potential value, estimated money saving and quality rating for used materials | |

| End product use mainly for themselves at home with aspiration for commercialisation | Provide specialised services such as business feasibility assessment, technical safety test and market identification | |

| Context for upcycling | Predominant use of home for upcycling | Provide tools hiring/rent service or lower membership price for Hackspace/Makerspace |

| Interest in good companions or collaborators | Provide a community event on a regular basis to enable people to identify collaborators, companions or business partners. | |

| Factors influencing upcycling | Particular benefits emphasised | Stress economic, environmental and emotional/psychological benefits when providing information about upcycling |

| Key factors | Key factors identified as intention, attitude and subjective norm | Design and prioritise interventions to shape intention, build positive attitude and establish positive subjective norm (culture) |

| Important demographic characteristics | Females, aged 30 years or older, working in art and design, and part-time or self-employment | Target 30+ females working in art and design for interventions |

| Action | Category | Elements | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Provide facilities (Enable) | Environmental restructuring/service provision/social planning |

|

|

| Ensure ability (Enable) | Education and training |

|

|

| Build understanding (Enable) | Persuasion/communication/marketing |

|

|

| Incentives (Encourage) | Incentivisation/fiscal/regulation/legislation |

|

|

| Lead by example (Exemplify) | Modelling |

|

|

| Intervention | Importance | Feasibility | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Community workshops | 3.52 | 0.71 | 3.60 | 0.87 |

| Novice toolkits | 3.25 | 1.15 | 3.67 | 1.09 |

| Upcycling centre | 3.72 | 1.10 | 3.48 | 0.96 |

| Materials provision service | 3.90 | 0.85 | 3.35 | 0.75 |

| Curriculum enrichment | 3.72 | 1.02 | 3.96 | 0.84 |

| Community events | 3.33 | 1.01 | 4.00 | 0.80 |

| Competitions | 2.84 | 1.21 | 4.12 | 0.88 |

| Business consulting | 3.26 | 0.96 | 3.65 | 0.88 |

| Communication | 3.16 | 1.25 | 4.04 | 0.86 |

| Campaign | 2.92 | 1.04 | 4.00 | 0.87 |

| TV and inspirational media | 3.60 | 0.87 | 4.12 | 0.78 |

| Incentives for upcycling businesses | 3.86 | 1.08 | 2.73 | 1.12 |

| Incentives for upcycling initiatives/research | 3.56 | 0.96 | 3.20 | 1.08 |

| Commissioned projects | 3.09 | 1.12 | 3.38 | 0.92 |

| Government procurement change | 3.64 | 1.11 | 2.84 | 1.31 |

| Intervention | Number of Answers (n) | Others Specified | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gov 1 | LA | Com | NGO | Des | Oth | ||

| Community workshops | 3 | 11 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 5 | Communities, volunteers |

| Novice toolkits | 1 | 2 | 10 | 8 | 8 | 1 | Communities |

| Upcycling centre | 4 | 20 | 3 | 8 | 0 | 2 | WRAP 2 |

| Materials provision service | 4 | 3 | 12 | 3 | 6 | 0 | NA |

| Curriculum enrichment | 13 | 5 | 1 | 0 | 6 | 9 | Educational institutions |

| Community events | 2 | 12 | 1 | 14 | 2 | 2 | Communities |

| Competitions | 6 | 7 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 12 | Educational institutions, communities |

| Business consulting | 2 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 3 | 2 | Business consultants, researchers |

| Communication | 9 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 6 | 3 | Communities, WRAP |

| Campaign | 2 | 3 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 1 | Communication specialists |

| TV and inspirational media | 1 | 0 | 5 | 11 | 10 | 6 | Broadcasters |

| Incentives for upcycling businesses | 20 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Incentives for upcycling initiatives/research | 20 | 2 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 3 | Research Councils, Arts Council |

| Commissioned projects | 6 | 3 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 0 | NA |

| Government procurement change | 22 | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | NA |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sung, K.; Cooper, T.; Kettley, S. Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling. Energies 2019, 12, 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12142778

Sung K, Cooper T, Kettley S. Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling. Energies. 2019; 12(14):2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12142778

Chicago/Turabian StyleSung, Kyungeun, Tim Cooper, and Sarah Kettley. 2019. "Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling" Energies 12, no. 14: 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12142778

APA StyleSung, K., Cooper, T., & Kettley, S. (2019). Developing Interventions for Scaling Up UK Upcycling. Energies, 12(14), 2778. https://doi.org/10.3390/en12142778