Organizational and Systemic Policy Capacity of Government Organizations Involved in Energy-From-Waste (EFW) Development in Thailand

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Context of the Alternative Energy Development Plan 2015

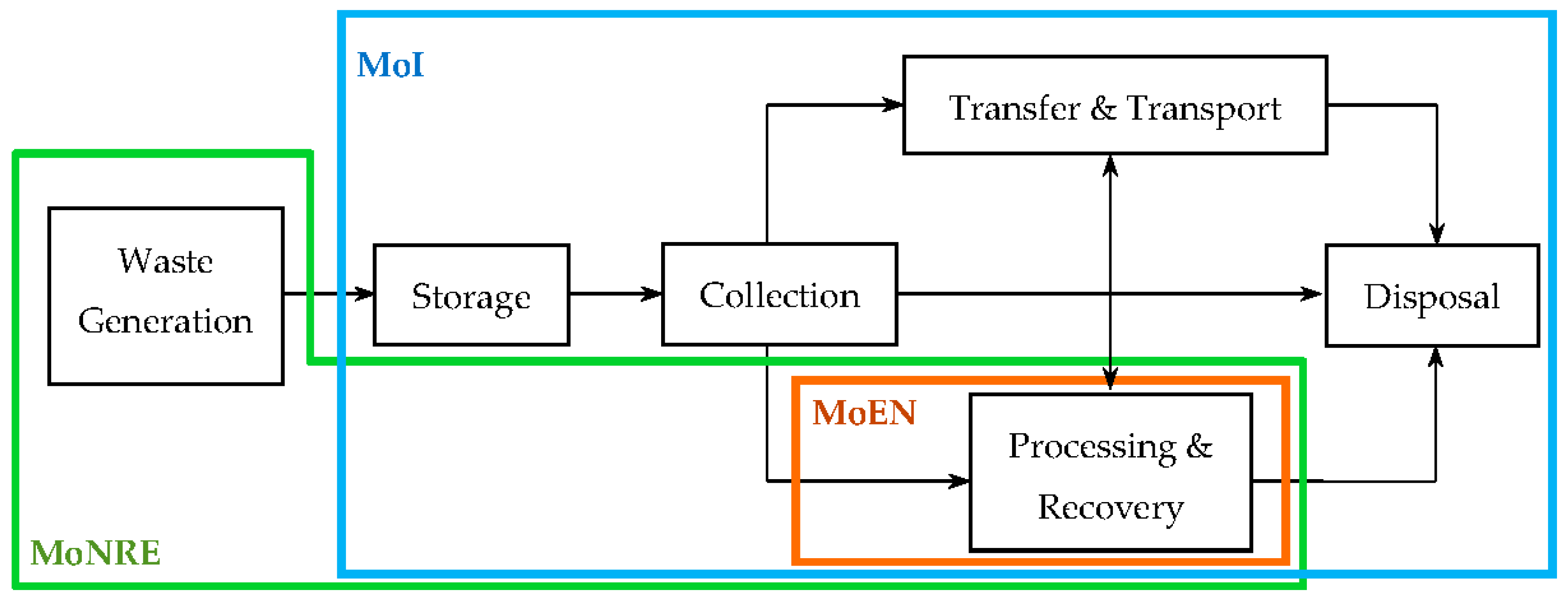

1.2. Major Government Organizations Involved in EFW Development

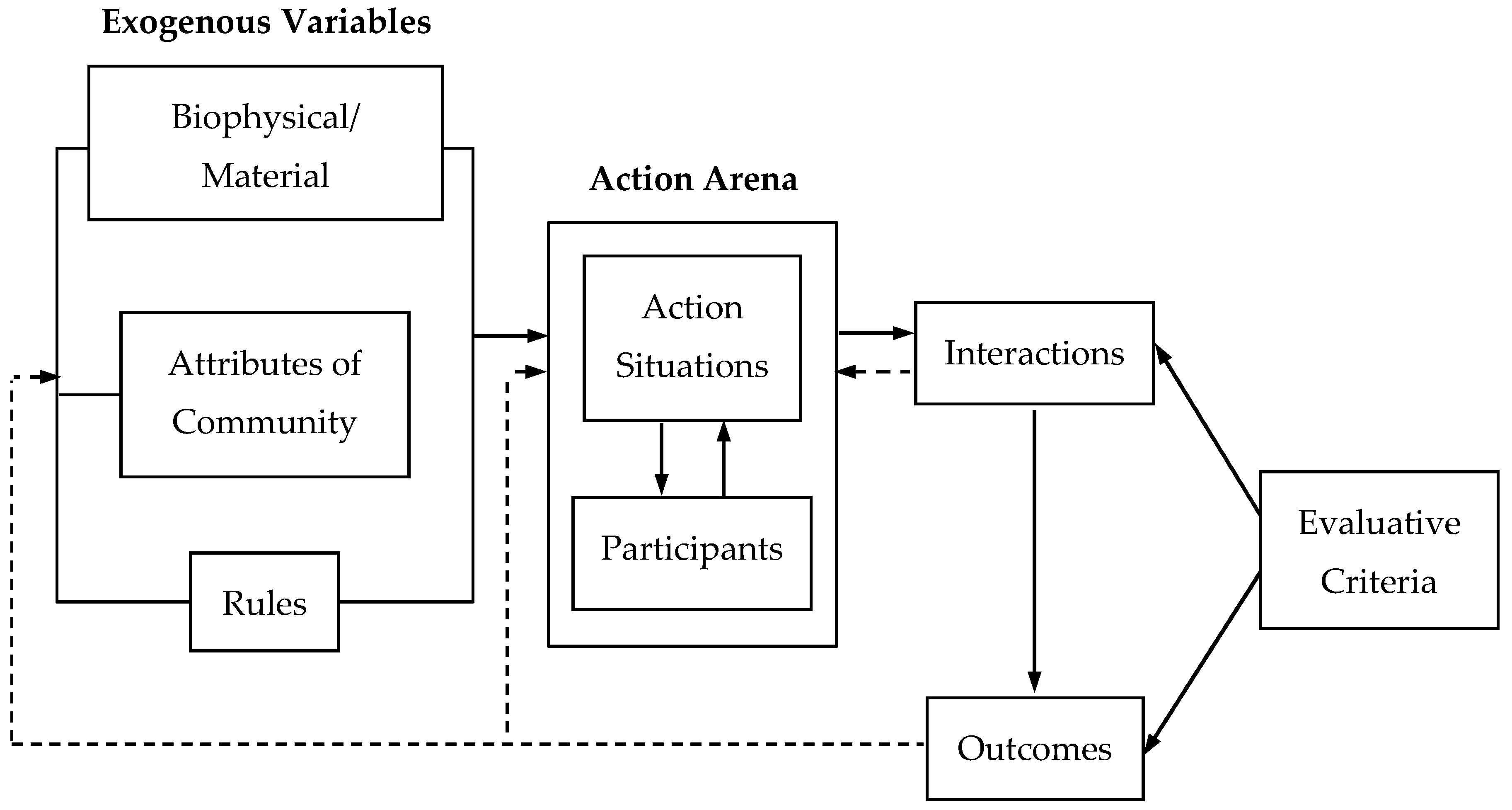

1.3. Institutional Analytical and Development Framework for Institutional Analysis

1.4. Conceptualization of Policy Capacity

2. Methodology

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Expert Interviews

3. Results

3.1. Factors Contributing to Policy Capacity

3.2. Key Findings and Recommendations for Analysing Policy Capacity

- (1)

- Skills—the abilities and expertise needed to conduct policy work effectively. Examples of these skills include analytical skills, coordination skills, and communication skills.

- (2)

- Resources—any supplies and support that an organization brings to the policy process, such as information, human resources, coordination, trust, political support, and legitimacy.

- (3)

- Processes that affect the decisions and actions required to conduct the policy work, for example, the communication process, internal and external coordination processes, and the stakeholder participation process.

3.3. Policy Capacity of the Thai Government

3.3.1. Ministry of Energy

3.3.2. Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment

3.3.3. Ministry of Interior

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Acronyms

| 3Rs | Reduce, Reuse, and Recycle |

| AEDP 2015 | Alternative Energy Development Plan 2015 |

| EEDP | Energy Efficiency Development Plan |

| EFW | Energy from waste |

| IAD | Institutional analytical and development |

| MoEN | Ministry of Energy |

| MoI | Ministry of Interior |

| MoNRE | Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment |

| PDP | Power Development Plan |

| SWM | Solid Waste Management |

| TIEB | Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint |

| WTE | Waste to energy |

References

- Energy Policy and Planning Office (EPPO). Thailand Integrated Energy Blueprint (TIEB). Available online: http://www.eppo.go.th/index.php/en/policy-and-plan/en-tieb/tieb-pdp#&Itemid=813 (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE). Alternative Energy Development Plan: AEDP2015; Department of Alternative Energy Development and Efficiency (DEDE): Bangkok, Thailand, 2015.

- Gleeson, D.; Legge, D.; O’Neill, D.; Pfeffer, M. Negotiating Tensions in Developing Organizational Policy Capacity: Comparative Lessons to be Drawn. J. Comp. Policy Anal. Res. Pract. 2011, 13, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polski, M.M.; Ostrom, E. An Institutional Framework for Policy Analysis and Design. In Workshop in Political Theory and Policy Analysis Working Paper W98-27; Indiana University: Bloomington, Indiana, February 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Srisaeng, N.; Tippayawong, N.; Tippayawong, K.Y. Energetic and Economic Feasibility of RDF to Energy Plant for a Local Thai Municipality. Energy Procedia 2017, 110, 115–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukholthaman, P.; Sharp, A. A system dynamics model to evaluate effects of source separation of municipal solid waste management: A case of Bangkok, Thailand. Waste Manag. 2016, 52, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vassanadumrongdee, S.; Kittipongvises, S. Factors influencing source separation intention and willingness to pay for improving waste management in Bangkok, Thailand. Sustain. Environ. Res. 2018, 28, 90–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makarichi, L.; Jutidamrongphan, W.; Techato, K. The evolution of waste-to-energy incineration: A review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2018, 91, 812–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menikpura, S.N.M.; Sang-Arun, J.; Bengtsson, M. Assessment of environmental and economic performance of Waste-to-Energy facilities in Thai cities. Renew. Energy 2016, 86, 576–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M. Policy capacity: A conceptual framework for understanding policy competences and capabilities. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollution Control Department (PCD). National Solid Waste Management Master Plan (2016–2021); Pollution Control Department (PCD): Bangkok, Thailand, 2016.

- Office of the Council of State (OCS) Act on the Maintenance of the Cleanliness and Orderliness of the Country, B.E. 2560. Available online: http://laws.anamai.moph.go.th/ewtadmin/ewt/laws/download/about_laws_2017/laws_concerned/Announce_07.pdf (accessed on 25 July 2018).

- Ostrom, E. Institutional Analysis and Development: Elements of the framework in historical perspective. Hist. Dev. Theor. Approaches Sociol. 2010, 2, 401. [Google Scholar]

- Wellstead, A.M.; Stedman, R.C.; Lindquist, E.A. The Nature of Regional Policy Work in Canada’s Federal Public Service. Can. Polit. Sci. Rev. 2009, 3, 34–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gleeson, D.H.; Legge, D.G.; O’Neill, D. Evaluating health policy capacity: Learning from international and Australian experience. Aust. N. Z. Health Policy 2009, 6, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howlett, M.; Ramesh, M. The two orders of governance failure: Design mismatches and policy capacity issues in modern governance. Policy Soc. 2014, 33, 317–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woo, J.J.; Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M. Legitimation capacity: System-level resources and political skills in public policy. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 271–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M. Policy Capacity: Conceptual Framework and Essential Components. In Policy Capacity and Governance; Wu, X., Howlett, M., Ramesh, M., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Germany, 2018; pp. 1–25. ISBN 978-3-319-54674-2. [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, A.; Gleeson, D.; Legge, D.; Lin, V. Governance and policy capacity in health development and implementation in Australia. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 229–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honadle, B.W. A capacity-building framework: A search for concept and purpose. Public Adm. Rev. 1981, 41, 575–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, S.N.; Nørgaard, O. Conceptualising state capacity: Comparing Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Polit. Stud. 2004, 52, 685–708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challenges to State Policy Capacity; Painter, M., Pierre, J., Eds.; Palgrave Macmillan UK: London, UK, 2005; ISBN 978-1-349-51825-8. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M. Policy analytical capacity and evidence-based policy-making: Lessons from Canada. Can. Public Adm. 2009, 52, 153–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlop, C.A. Organizational political capacity as learning. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 259–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattyn, V.; Brans, M. Organisational analytical capacity: Policy evaluation in Belgium. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 183–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, B.G. Policy capacity in public administration. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 219–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M.P.; Wu, X. Rethinking Governance Capacity as Organizational and Systemic Resources. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angel, H. Measuring policy analytical capacity for the environment: A case for engaging new actors. Policy Soc. 2015, 34, 197–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, J.A.; Osborn, M. Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. In Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis; SAGE: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Howlett, M.; Wellstead, A.; Craft, J. Policy Work in Canada: Professional Practices and Analytical Capacities in Canada’s Policy Advisory System; Michigan Tech: Houghton, MI, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ramesh, M.; Howlett, M.P.; Saguin, K. Measuring Individual-Level Analytical, Managerial and Political Policy Capacity: A Survey Instrument. SSRN Electron. J. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.J. Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Tax Cuts. Public Opin. Q. 2009, 73, 144–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, T.J.; Evans, J. Political Trust, Ideology, and Public Support for Government Spending. Am. J. Pol. Sci. 2005, 49, 660–671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thissen, W.A.H.; Twaalfhoven, P.G.J. Towards a conceptual structure for evaluating policy analytic activities. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2001, 129, 627–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiernan, A.; Wanna, J. Competence, capacity, capability: Towards conceptual clarity in the discourse of declining policy skills. In Proceedings of the GovNet International Conference, Canberra, Australia, 28 November 2006. [Google Scholar]

| Organizations | Documents |

|---|---|

| MoEN | AEDP 2015 |

| AEDP 2015 Action Plan | |

| Renewable and alternative energy annual reports | |

| MoNRE | The National Solid Waste Management Master Plan (2016–2021) |

| Waste management annual reports | |

| MoI | Action Plan “Thai Zero Waste” (2016–2017) |

| Action Plan “Clean Province” (2018) | |

| Act on the Maintenance of the Cleanliness and Orderliness of the Country, B.E. 2560 |

| Context | Year | Authors | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical framework | 2015 | Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett | [10] |

| 2018 | Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh | [18] | |

| Policy capacity at organizational level | 2015 | Dunlop | [24] |

| 2009 | Gleeson et al. | [15] | |

| 2011 | Gleeson et al. | [3] | |

| 2015 | Hughes | [19] | |

| 2015 | Pattyn and Brans | [25] | |

| 2015 | Peters | [26] | |

| 2016 | Ramesh, Howlett, and Wu | [27] | |

| 2015 | Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett | [10] | |

| 2018 | Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh | [18] | |

| Policy capacity at systemic level | 2015 | Hsu | [28] |

| 2015 | Hughes | [19] | |

| 2016 | Ramesh, Howlett, and Wu | [27] | |

| 2015 | Woo et al. | [17] | |

| 2015 | Wu, Ramesh, and Howlett | [10] | |

| 2018 | Wu, Howlett, and Ramesh | [18] |

| Organizations | Number of Interviewees | Contributions in AEDP 2015 and/or EFW |

|---|---|---|

| MoEN | 5 | Setting agendas, formulating, and making decisions for AEDP 2015 |

| MoNRE | 2 | Setting agendas, formulating, and regulating the National Solid Waste |

| Management Master Plan | ||

| Approving funding for local administrative organizations | ||

| MoI | 2 | Operating the waste management system |

| Level of Policy Capacity | Factors Contributing to Policy Capacity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Skills | Operational Skills | Political Skills | |

| Organizational Level |

|

|

|

| Systemic Level |

|

|

|

| Level of Resources and Capabilities | Policy Capacity | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Analytical Skills | Operational Skills | Political Skills | |

| Organizational level |

|

|

|

| Systemic level |

|

|

|

| Policy Capacity Component | Categorized Factors Contributing to Policy Capacity | Government Organizations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MoEN | MoNRE | MoI | ||

| Organizational Analytical Capacity | Skills: Information acquiring and processing | Abilities in acquiring and processing the required information for policy were demonstrated. | The MoNRE can acquire and process the required information necessary for policy works. | Not mentioned. |

| Resources: Adequately skilled staff, time, and tools for information analysis and evaluation | Even though the MoEN applies various tools for helping analyze and evaluate the acquired information, more human resources are still required due to the quality of the information. | The MoNRE uses different analytical information and evaluation needed to overcome the limitation of human resources. | Not mentioned. | |

| Processes: Information acquisition, analysis, dissemination, and evaluation | Different processes and methods were used to acquire and process the required information, such as sending formal letters and questionnaires, discussing with relevant organizations, cross-checking the received information, and forecasting the missing information. | The inspection manual was used by local organizations to evaluate the situations and information for the MoNRE. Moreover, sending formal letters, discussing with the relevant organizations, and searching for the required information from secondary data were also used. | The MoI disseminated the existing information when there was a request from other organizations. | |

| Organizational Operational Capacity | Skills: Leadership and management | The MoEN prepared counterplans for the flexibility in conducting future activities and projects if the approved budget was lower than the expectation. | The MoNRE plans to solve the inadequate budget by encouraging coordination from private sectors. | The MoI manages and directs its policy activities and projects through the cooperation of local delegates such as community leaders, teachers, and monks. |

| Resources: Information, human resources, and financial resources | The MoEN required more staff to deal with various information sources related to policy works. Moreover, the expected budgets for AEDP 2015 might be adjusted by government. | The MoNRE faced the challenge of inadequacy of timely and updated information, human resources, and the approved budget. | The MoI requires information, human resources, and financial resources to establish and operate 18 waste collection centers effectively; however, the expected annual budget might be changed by the government. | |

| Processes: External and internal coordination | Internally, the MoEN set all energy plans consistently to support each other. Externally, the MoEN tried sharing information, communicating, and consulting with other organizations to adjust the energy plans in harmony with other relevant policies. | The MoNRE consulted and coordinated internally to adjust the regulations for renewable energy plan approval. Externally, the MoNRE consulted and shared information with the MoI to establish the action plans to support the National Solid Waste Master Plan. | The MoI communicated and cooperated internally to conduct policy works among teams. Externally, the MoI worked with the MoNRE to establish action plans to support the waste management roadmap, and shared its information with relevant organizations. | |

| Organizational Political Capacity | Skills: Communication and persuasion | The MoEN communicated within and outside organizations to gain support for policy works with different groups of stakeholders. | The MoNRE communicated with other organizations to share information and gain support for its policy works. | The MoI mainly communicated and persuaded local authorities to participate and support its policy works. |

| Resources: Legitimacy for policy process, and stakeholders’ information | The MoEN used the information of different groups of stakeholders to establish and implement energy policies consistent with the direction and final decision made by the government. | The MoNRE was assigned by the government to solve the waste management problem urgently by setting up the waste management roadmap. | The MoI was assigned by the government to establish the waste management action plans and work corporately with the MoNRE to solve waste management problems. | |

| Processes: Access to key policy-makers, and internal and external communication | The MoEN accessed key policy-makers through formal proposals and reports. Moreover, the MoEN analyzed and consulted within organizations to select some special groups of stakeholders, such as energy experts. | The MoNRE accessed key policy-makers by raising the waste management problem and causing it to be on the national agenda. | The MoI consulted and communicated with the MoNRE for support of the waste management action plans. | |

| Systemic Analytical Capacity | Skills: Information collecting, analyzing, evaluating, and disseminating | The MoEN tried collecting the received information, and analyzed, evaluated, and disseminated it -systematically within the organization. | The MoNRE tried analyzing and evaluating the received information systematically. | The MoI lacks the skills in collecting and disseminating information systemically. |

| Resources: Efficiency and transparency of information system including channels for stakeholder participation | The MoEN lacks an effective and transparent information system and formal channels for stakeholder participation in the information system. | The MoNRE lacks an effective and transparent information system and formal channels for stakeholder participation in the information system. | The MoI lacks an effective and transparent information system and formal channels for stakeholder participation in the information system. | |

| Processes: Information collecting, processing, evaluating, and disseminating | The MoEN used different techniques to process and evaluate the received information, then collected and disseminated the information within the organization through internal reports and discussions. | The MoNRE used different techniques to process and evaluate the received information and disseminate the information through annual reports, meetings, and discussions. | The MoI requires a standard format for information collection and central channels to disseminate accurate and timely information to the relevant organizations. | |

| Systemic Operational Capacity | Skills: Communication and control over stakeholders, and building and maintaining relationships | The MoEN communicated with other organizations and stakeholders to build and maintain support for policy works. | The MoNRE communicated with other organizations to maintain their relationships and to monitor policy implementation. | The MoI communicated and controlled the local authorities to build and maintain their relationships for the support of policy works. |

| Resources: Coherence and engagement of policy networks and communities, and clarity in roles and responsibilities | The MoEN tried working coherently, especially with private sectors and local communities. | The MoNRE requires clarity in roles and responsibility, especially as a regulator of the MoI. | The MoI works closely with local authorities and communities. | |

| Processes: Communication and negotiation | The MoEN communicated and negotiated with stakeholders through the public hearing process to balance the interests and benefits of all stakeholders. | The MoNRE communicated with stakeholders through the public hearing process and negotiated with relevant organizations through discussions and consultations. | The MoI communicated and negotiated with stakeholders, especially local authorities, through public hearings and different policy activities. | |

| Systemic Political Capacity | Skills: Enabling stakeholder participation, and skills in managing policy activities | The MoEN showed effective abilities in enabling stakeholder participation by arranging various policy activities to gain support from different sectors of stakeholders. | The MoNRE enabled stakeholder participation and managed different policy activities. | The MoI received good participation in different policy projects and activities from local authorities, communities, and private sectors. |

| Resources: Level of stakeholder participation, public support, legitimacy, and trust. | AEDP 2015 was supported by various sectors which reflected a high level of stakeholder participation and interest during the policy process, especially public hearings. However, stability and continuity of the policy and incentive measures were questioned by the private sector. | Level of stakeholder participation was not mentioned. However, the MoI supports the MoNRE and works with locals concerned about the continuity of policy projects and activities launched by the MoNRE. | High level of stakeholder participation and public support was reflected in different policy activities and projects. However, the discontinuity of past projects and activities might affect the level of participation in future. | |

| Processes: Stakeholder participation | Public hearings, focused group meetings, and expert discussions were the processes used by the MoEN to encourage stakeholder participation. | The MoNRE uses public hearing processes for stakeholder participation. | Similar to the MoEN and the MoNRE, the MoI also uses public hearings as the main process for stakeholder participation. | |

© 2018 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Chenboonthai, H.; Watanabe, T. Organizational and Systemic Policy Capacity of Government Organizations Involved in Energy-From-Waste (EFW) Development in Thailand. Energies 2018, 11, 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11102501

Chenboonthai H, Watanabe T. Organizational and Systemic Policy Capacity of Government Organizations Involved in Energy-From-Waste (EFW) Development in Thailand. Energies. 2018; 11(10):2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11102501

Chicago/Turabian StyleChenboonthai, Haruthai, and Tsunemi Watanabe. 2018. "Organizational and Systemic Policy Capacity of Government Organizations Involved in Energy-From-Waste (EFW) Development in Thailand" Energies 11, no. 10: 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11102501

APA StyleChenboonthai, H., & Watanabe, T. (2018). Organizational and Systemic Policy Capacity of Government Organizations Involved in Energy-From-Waste (EFW) Development in Thailand. Energies, 11(10), 2501. https://doi.org/10.3390/en11102501