Mandibular fractures are the second most common fractures of the face after the nasal bones. [

1] Mandibular symphyseal fracture accounts for 15.6 to 29.3% of mandibular fractures. [

2,

3]

Tooth loss in the fracture line is a known characteristic of jaw fractures. [

4] Indications for removal of the tooth in the fracture line are unrestorable crown, crown/root fractures, vertical root fractures, and severe periodontal disease. [

5] The basic principle is to retain the tooth in the fracture line as much as possible to help register the occlusion accurately, especially in the symphyseal area. [

6]

Tooth loss occurs as a result of avulsion or intentional extraction during the treatment of mandibular fractures. Forgetting the principle of “restoring preinjury occlusion” in the treatment of mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fractures with incisor tooth loss may cause problems in obtaining acceptable occlusion and facial esthetics as well as prosthodontic problems.

Materials and Methods

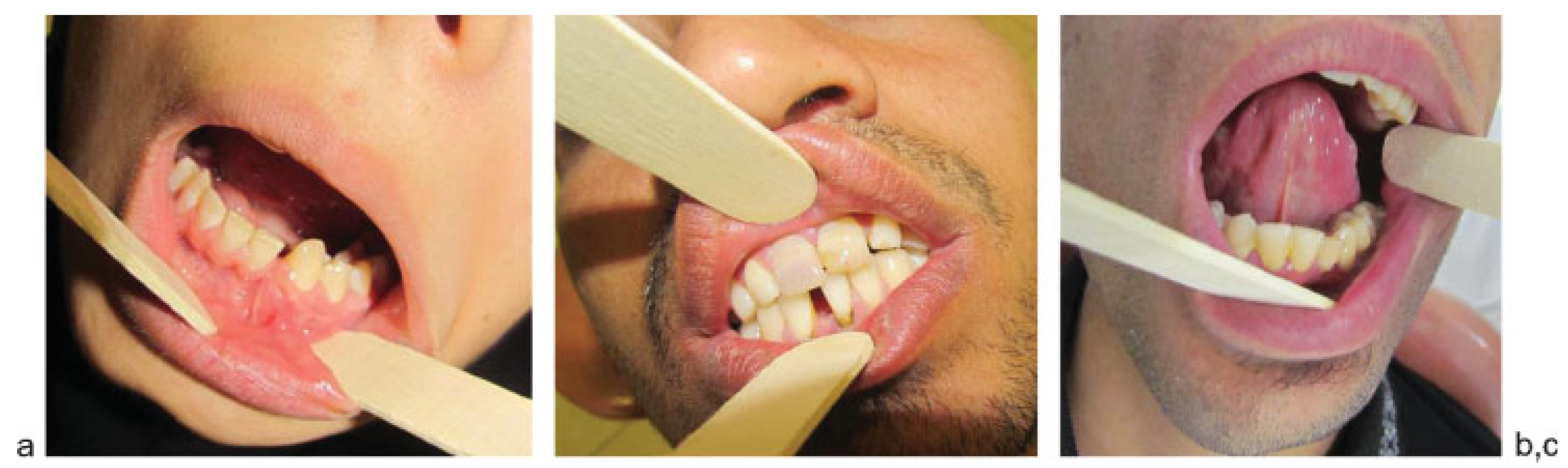

All the procedures were approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee (number 922450). In a retrospective study, patients with mandibular symphyseal/parasymphy-seal fractures, who had been operated in 2012 to 2013 in Emdadi Hospital, Mashhad University, Iran, were recalled. Patients with maximum 1-year follow-up were included in this study to mitigate the factor of tooth movement near the lost tooth and its effect in this study. Symphyseal/para-symphyseal fracture was defined as fracture line in mandibular bone between the canine teeth. These patients had not been treated by the same surgeon or the same technique. Patients with the loss of mandibular incisor tooth/ teeth in the fracture line were included in the study. Space loss was defined as remaining space insufficient for replacement of the lost incisor or decreased incisor tooth counts in intercanine space in the case of complete space closure. This ranged from slight to complete space loss (

Figure 1). Methods by which the lost incisor(s) had been replaced were recorded. Control panoramic radiographs and photographs from each jaw and in the occlusion were obtained.

Upper and lower jaw study casts were made with alginate impression material and poured in dental stone. Upper-lower dental midlines were checked. Combination fractures or fractures in other facial skeleton were noted. Type of treatment, including closed or open reduction, was recorded. In the open reduction group, type of incision for access to the fracture line (intraoral, extraoral surgical incision, or through facial laceration) and finally type of internal fixation devices (wire, lag screw, miniplate, etc.) were noted.

Results

Of 98 patients with mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fractures that responded to the recall, 22 had mandibular incisor loss (22.5%). Twenty-eight patients had another facial fracture, including zygoma, nose, or Le Fort fractures. Among them, 16 patients (73%) had space loss in the mandibular dental arch. Only 36 patients had isolated mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture. Forty patients had multiple mandibular fractures with the accompanying condylar fracture (30%) at the top of the list.

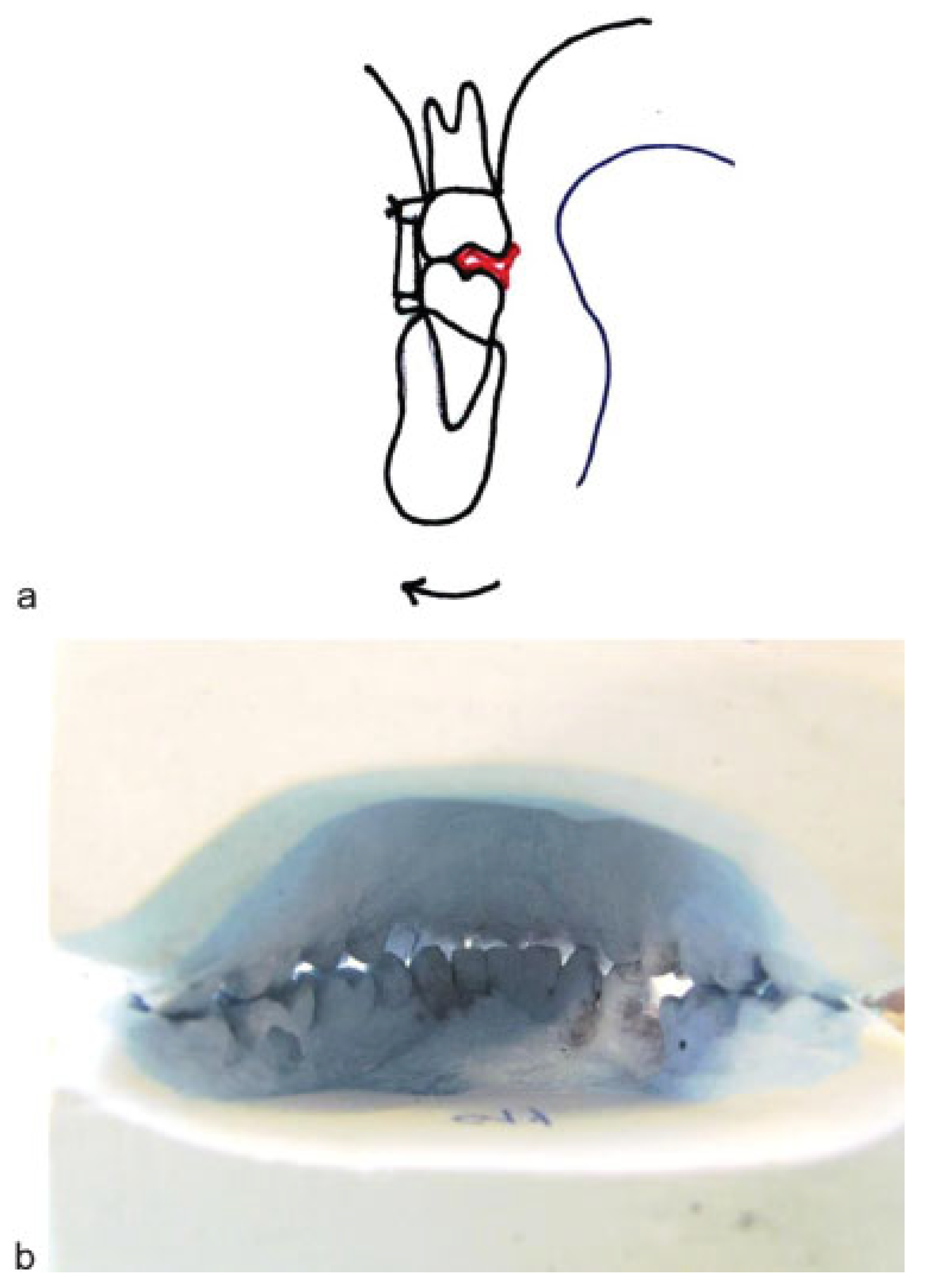

Twenty-two patients with mandibular symphyseal/para-symphyseal fracture and incisor tooth loss that included in the study have mean age of 32 ± 5.8. Male:female ratio was 4:5. Demographic information of these patients is demonstrated in

Table 1. Loss of four incisor teeth with the least frequency rate (9%) and one incisor tooth with the highest frequency rate (54.5%) were at the bottom and top of the list, respectively. Only four patients had replaced the lost incisors with dental prosthetic appliances, all with multiple incisors lost. Removable partial denture was the only method used for multiple incisor teeth loss but with artificial teeth, less in the count in comparison with what should have been replaced (

Figure 2).

Upper and lower dental midlines could not be evaluated in 10 patients because of the lost maxillary incisors or tooth loss that included both mandibular central incisors. In remaining patients (12 patients), the upper and lower dental midlines were off, although we had no documents to evaluate the pretrauma state of the midlines in these patients. All the patients except one had been treated with open reduction and internal fixation with miniplates. Extraoral access to the symphyseal bone had been used in eight patients.

Discussion

Postoperative occlusal discrepancy is less prominent when the tooth in the line of fracture is preserved. [

7] Space problem is more prominent in mandibular anterior region because of thin cortical bones and comminuted fractures. Tightening the wires passed in two sides of fracture line permits the fractured segments to come closer. Considering the mobility of the teeth adjacent to the fracture line, this movement will cause some problems in the fabrication of prosthetic appliances, occlusion, and facial esthetic.

Available space for prosthodontic replacement of the lost tooth is an important factor. In all the cases in which one incisor tooth had been lost, resulting in space loss (if the space had not been closed completely), the edentulous space had been left neglected without prosthetic replacement.

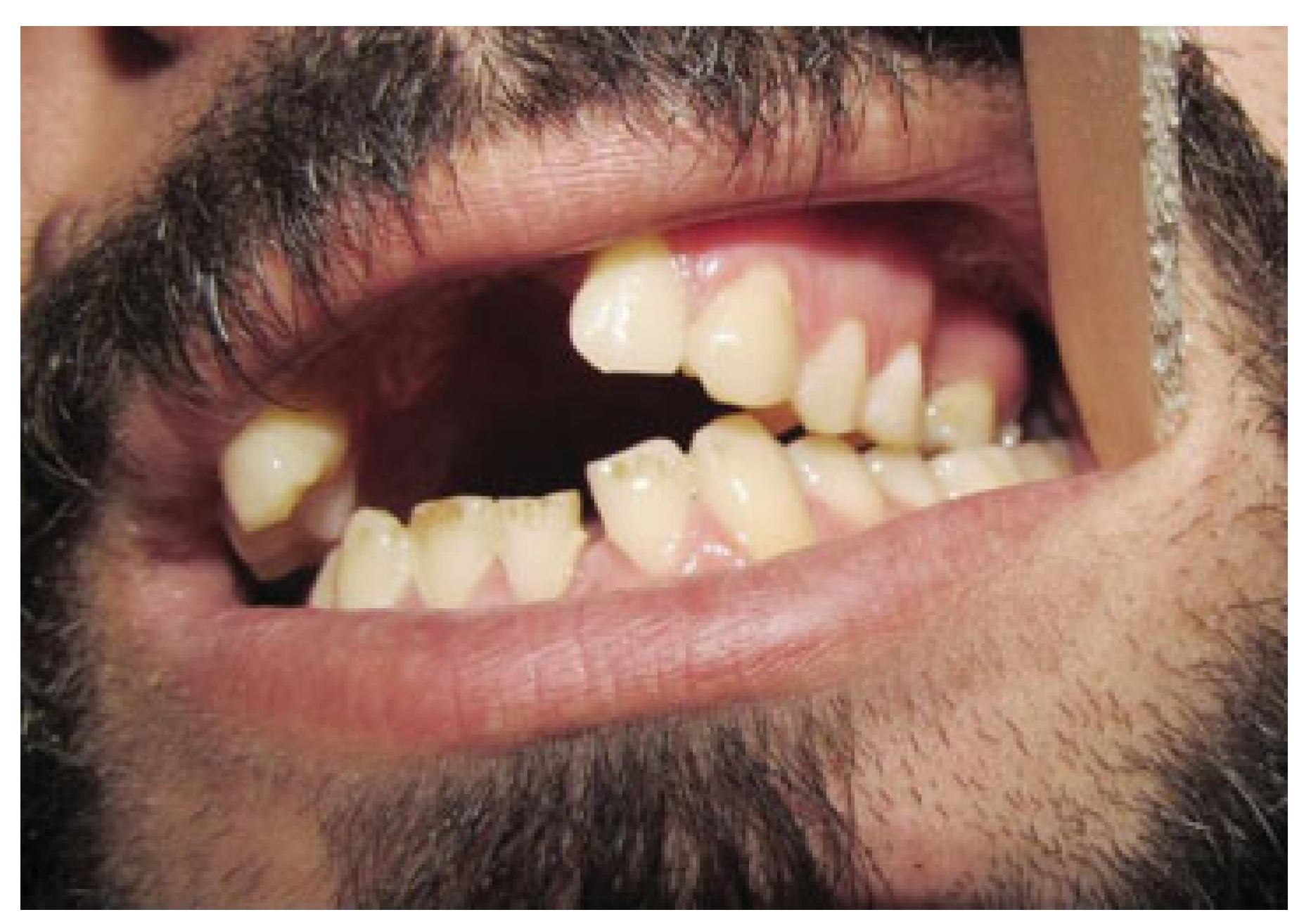

Occlusion is also influenced by this error. The classic occlusal problems were observed in cases in which symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture was not accompanied with maxillary fractures. In such cases, mandibular symphyseal fracture leads to dental arch narrowing in anterior mandible and widening in posterior segment, especially if it is accompanied with mandibular condylar fractures. [

8] A gap in the mandibular inferior border appears on radiographs when this error in the treatment happens and the lingual cusps of the mandibular posterior teeth fall out of the occlusion (

Figure 3).

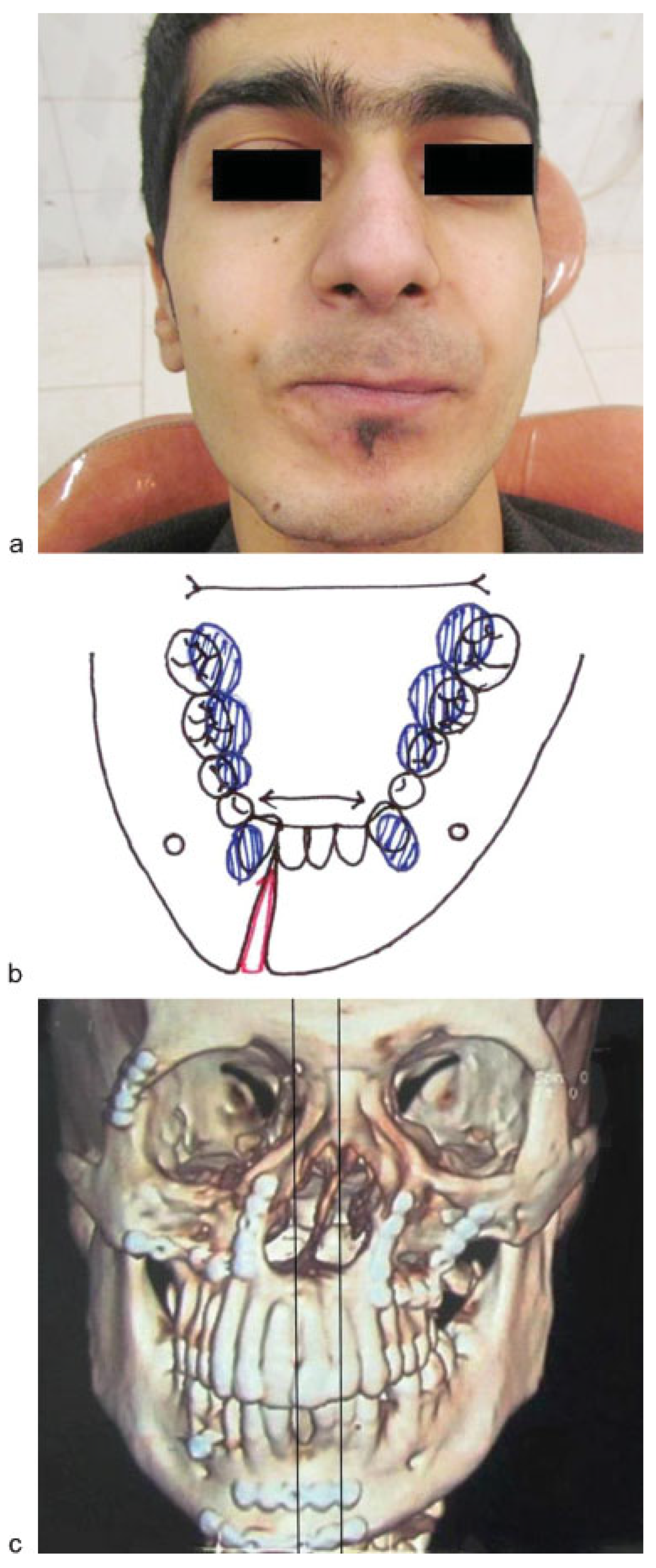

Maxillary fractures that involve the palate and alveolar arch, especially the sagittal and parasagittal fracture of the palate, often lead to widened maxillary dental arch in the anterior region. [

9] Combination of these two fractures without width control leads to grave prosthodontic problems (

Figure 4).

Facial esthetic problems are the other feature of this error. Mandibular asymmetry in the chin, when the incisor tooth loss is unilateral to the midline and the space is closed, is the rule. The facial asymmetry is less than expected. The reason may be the fact that slight space closure has no negative effect here and the fact that at least some part of the space closed is dental rather than skeletal. This asymmetry may extend to other parts of the face, when panfacial fracture happens and decision is to use the mandible as the reference (bottom-to-top concept) and the mandibular symphyseal fracture is the starting point for fixation. In this condition, it is our opinion not the fact from the results of this study that closure of the lost space in the mandibular incisor region in panfacial fracture patients causes facial asymmetry that affects the whole face (

Figure 5).

The fact that most patients with space loss belonged to the open reduction and internal fixation group does not show that this method is inferior to the closed treatment method. Its explanation is that the more severe the injury, the greater the need for open reduction and internal fixation for treatment of symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture.

The prevention of these problems is possible if the surgeon is aware of such a complication. Maintaining the space with simple appliances such as braided wires or the cut end of a plastic needle cup between the two segments is the solution (

Figure 6). Retaining the fractured root cannot prevent loss of the space.

The treatment of established malocclusion as the result of this error is difficult. Regaining the space in slight space loss might be possible by orthodontic tooth movements, but in more severe cases, it needs corrective surgery.

Mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal osteotomy (straight cut) with bone graft or sliding monocortical osteotomy without bone graft is the suggested surgical procedure. Osteodistraction is the other option.

Theoretically, extraoral incisions that expose labial, lingual, and inferior mandibular border permit the surgeon to check the fracture line from several aspects. [

9] The presence of posterior teeth, if used for maxillomandibular fixation, can also mitigate this problem.

Conclusion

Space loss after mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fracture with incisor tooth loss is a common error. The most important factor to prevent complications related to space loss following mandibular symphyseal/parasymphyseal fractures accompanying incisor tooth loss is space preservation.