The orbitozygomatic fracture is one of the most commonly encountered maxillofacial injuries. Many epidemiological studies have investigated the incidence of facial injuries around the world and all report low infection rates. Ellis et al. in Scotland report 2,067 cases over a 10-year period but no data on postoperative infections [

1], Gomes et al. in Brazil report 1,857 cases over a 5-year period with a 6.20% infection rate [

2], Haug et al. in the United States report 402 cases over a 5-year period with no data on infection rates [

3], Tadj and Kimble from Australia reported 263 cases over a 10-year period with complications discussed but no infection rate [

4], Bogusiak et al. in Europe report 468 cases over a 12-year period with an infection rate of 1.5% [

5], and Calderoni et al. report 141 cases over a 7-year period with an infection rate of 7.8% [

6].

The RBWH is a 929-bed quaternary and tertiary referral teaching hospital; with a large maxillofacial unit accepting patients from as far away as central, far western Queensland as well as serving patients from northern New South Wales and the Pacific Rim [

7]. It has a well-established trauma service with maxillofacial surgery playing an integral role.

This study aims to review orbitozygomatic fractures in a tertiary referral center and present their outcomes, complications, and, in particular, infection rate, and to suggest whether antibiotic use is appropriate.

Material and Methods

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the RBWH, Metro North Health Service District. Approval Number: HREC/12/QRBW/170.

We conducted a retrospective case selection study using the RBWH Database of Queensland Health [

8], which prospectively registers all maxillofacial cases at the RBWH from January 1, 2011, to December 31, 2011. All adult patients with orbitozygomatic fractures were included. Patients were excluded if they were younger than 14 years and 6 months, had isolated orbital fractures, and had fractures involving more than the orbitozygomatic complex. Data were reviewed for the admission and consecutive follow-up examinations at 1-, 2-, and 6-week postoperative period. Clinical assessments and plain film radiographs were performed to document the progress and complications of these fractures such as implant failure, reoperations, and potential infections.

The current standard protocol at the RBWH for surgical management of orbitozygomatic fractures involves the use of prophylactic intravenous ampicillin with metronidazole in all cases. These are started preoperatively and continued for 24 h postoperatively. Patients with compound wounds are also commenced on oral antibiotics for 1 week postsurgery. They are assessed day 1 postoperative both clinically and with plain film radiographs. Patients are reviewed at 1, 2, and 6 weeks postoperatively.

Results

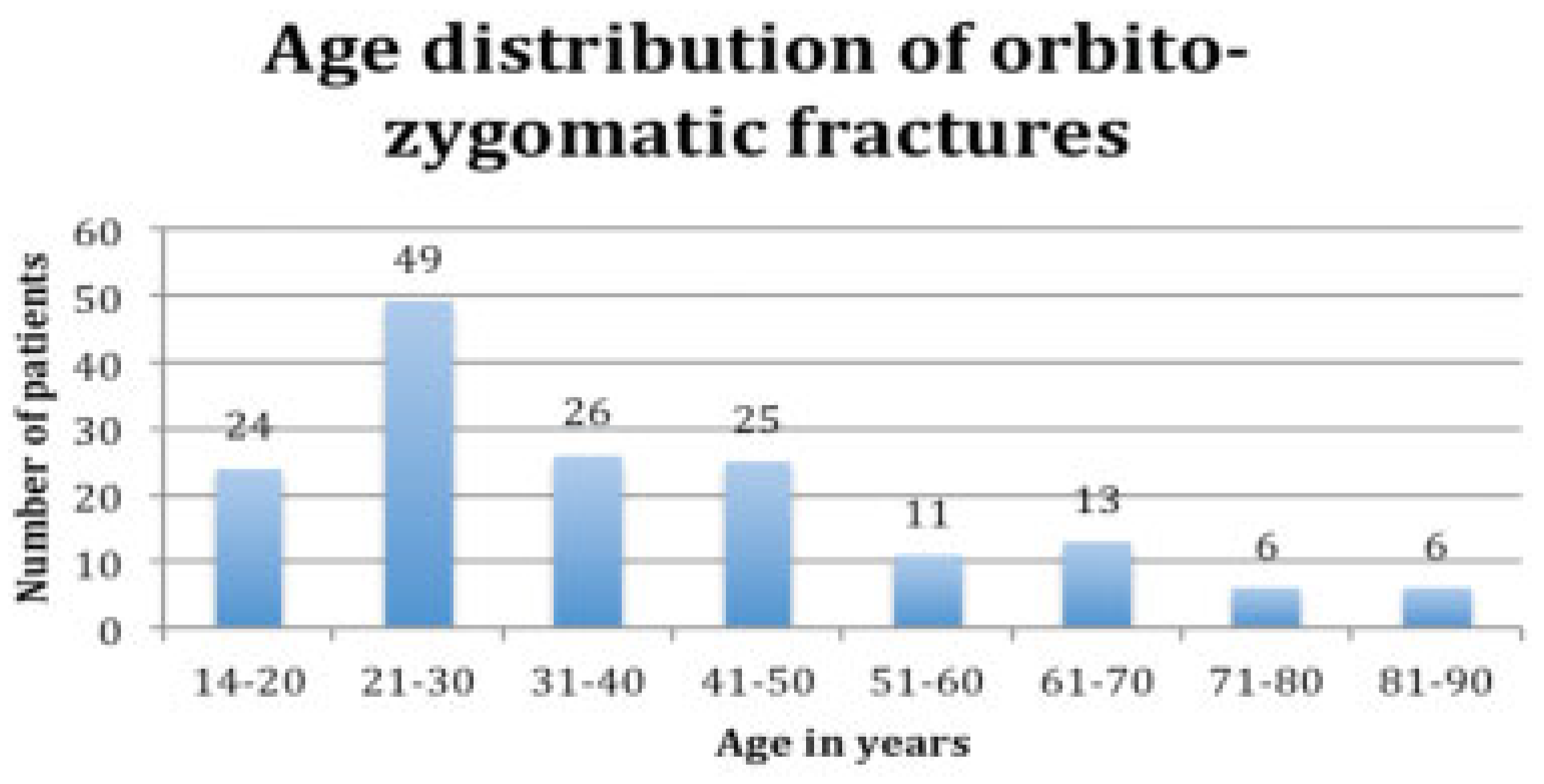

The mean age of patients with an orbitozygomatic fracture was 37.8 years with a range of 15 to 85 years. There were 140 males (87.5%) and 20 females (12.5%). The most common age group to have had an orbitozygomatic fracture was in the third decade of life (

Figure 1).

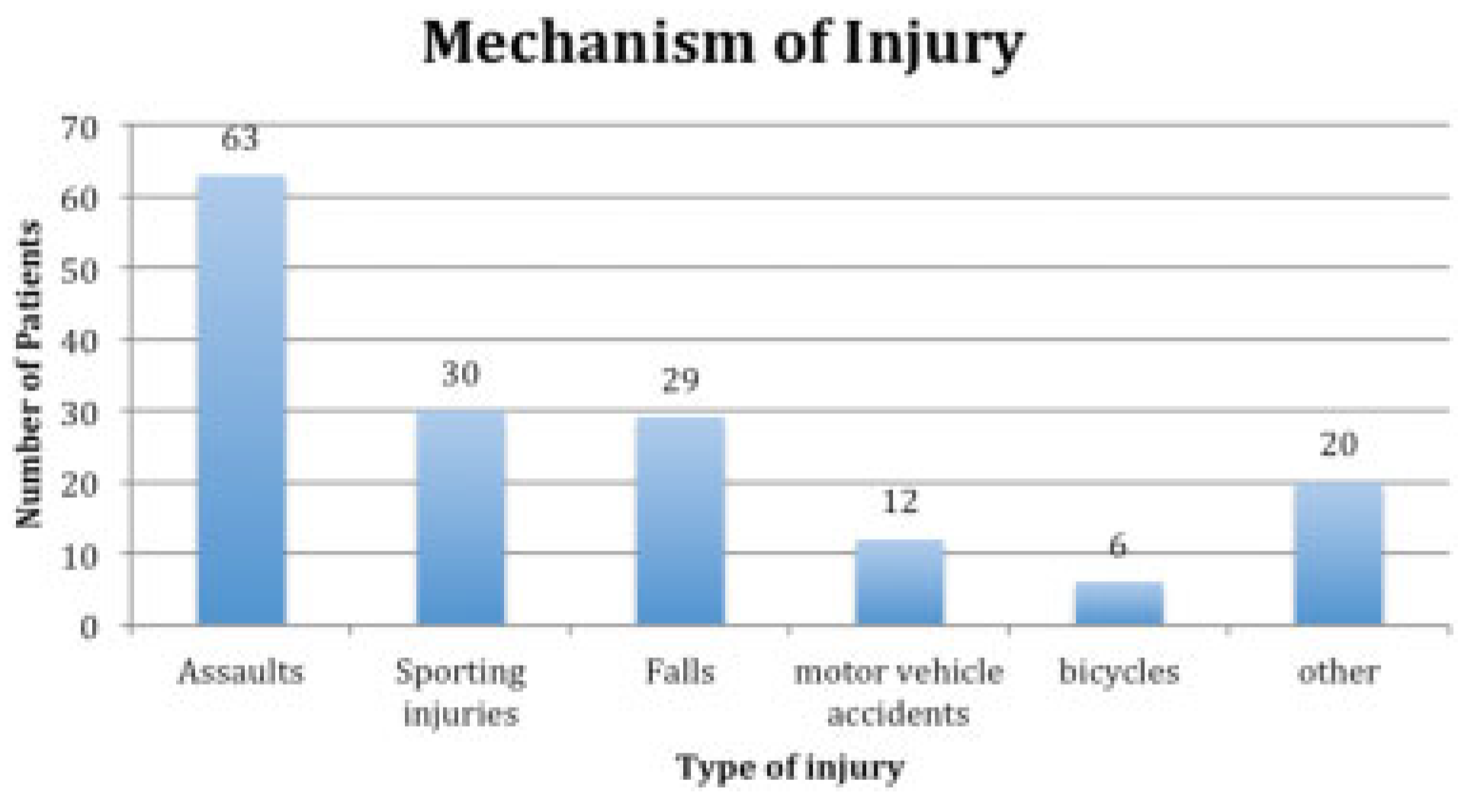

Alleged assaults accounted for 63 cases (39.4%) of mechanism of injury; 30 cases (18.8%) were attributed to sporting injuries; 29 cases (18.1%) were due to falls mechanical or medical; 12 cases (7.5%) were due to motor vehicle accidents; 6 cases (3.8%) due to bicycles; and 20 (12.5%) cases were attributed to other causes (

Figure 2).

In 40 cases (25.0%), the patients admitted taking alcohol and 2 (1.3%) cases admitted using recreational drugs such as amphetamines, marijuana, or cocaine.

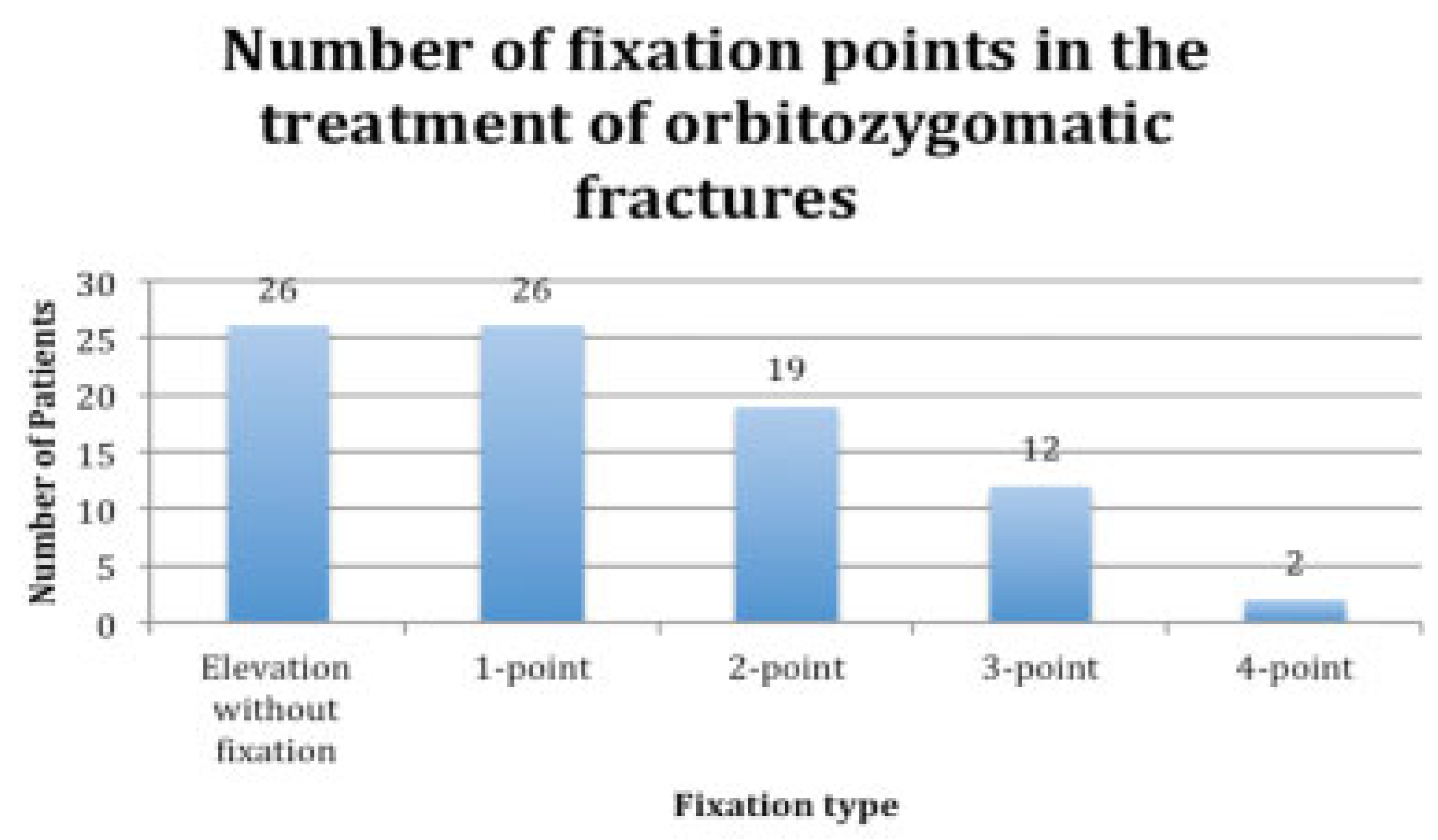

There were 160 orbitozygomatic fractures managed at the RBWH in 2011. Eighty-five cases (53.1%) were treated surgically. Reduction without fixation and one-point fixation were equally the most commonly used techniques in the surgical treatment of orbitozygomatic fractures (

Figure 3).

The average waiting time to surgery was 3.7 days. Seventeen patients (20%) received their operations on the same day as their injury whereas 54 patients (63.5%) waited 4 days or less for their surgery.

In total, 75 cases (46.9%) were managed conservatively. The same follow-up regime as the operatively treated group was conducted, and all had excellent results as determined at the 6-week follow-up appointment. Three of the surgical cases (1.9%) had complications that required further surgery. Two cases were due to inadequate cosmesis and one was due to exposure of the mini-plate requiring its removal along with the screws. Specifically, there were no complications of an infective nature.

The first complication involved a 32-year-old man injured due to an alleged assault, resulting in a severe left orbitozygomatic fracture. The patient had paraesthesia to the distribution of the left infraorbital nerve (

Figure 4).

The patient had resolution of the infraorbital paraesthesia after the first reduction; however, he complained of an inadequate aesthetic result (

Figure 5).

The patient underwent reoperation with removal of the fixation, correct anatomical reduction, and refixation with mini-plates. The postoperative result was excellent with the patient being discharged from outpatient care 6 weeks after the second procedure.

The second complication is of a 28-year-old man injured due to an assault. There was an anatomical defect in the left zygomatic arch (

Figure 6).

The arch was reduced via the Gillies’ approach. This resulted in inadequate reduction, poor cosmesis, and subsequently the patient returned for appropriate correction. The second procedure was repeat reduction without fixation via the same approach (

Figure 7).

The third complication involved a 21-year-old man who sustained a right orbitozygomatic injury due to an assault. The six-hole mini-plate became exposed intraorally after 3 months. It was removed uneventfully under general anesthesia (

Figure 8).

Discussion

This study examined the incidence and complications of orbitozygomatic fractures at a tertiary referral center of the RBWH with good outcomes and a very low complication rate. Orbitozygomatic injuries account for approximately 20% of maxillofacial injuries and 30 to 45% of all mid-face fractures [

9,

10].

There were 160 orbitozygomatic fractures treated at the RBWH in 2011. This number represents the cases seen in the RBWH maxillofacial unit alone. There are four other units in Queensland that treat facial injuries. There were no cases of early postoperative infection. Infection rates in the literature range from nil to 7.8% [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6].

There are no randomized controlled trials looking at the use of antibiotics in the surgical treatment of orbitozygomatic fractures. Knepil and Loukota report a wide variation in use of antibiotic regimes with surgical repair of orbitozygomatic fractures and that the infection rate is low at 1.5% [

11]. Andreasen suggests a one-shot or 1-day administration of a range of prophylactic antibiotics in any fracture of the facial skeleton. There was a similar very low infection rate with antibiotics used over 7 days and there were no infections related to zygomatic fractures [

12].

Antibiotic Use

Australian therapeutic guidelines suggest that antibiotic prophylaxis should be considered for procedures that involve an incision through oral, nasal, pharyngeal, or esophageal mucosa, or the insertion of prosthetic material. According to these guidelines, a single dose of antibiotics is usually sufficient, but if the procedure is not completed within 3 h of initiating prophylaxis, a second dose should be given. It is suggested that intravenous cephazolin 1 g (adult 80 kg or more: 2 g) (child 25 mg/kg up to 1 g) be given at the time of induction [

13].

Antibiotics are selected on cost, safety, pharmacokinetic profile, and bactericidal activity. Intravenous ampicillin and metronidazole are used at the RBWH as prophylaxis for common oral flora such as streptococci, lactobacilli, staphylococci, and Bacteroides anaerobes particularly with oral mucosal incisions. For patients with allergies or reactions to penicillin, lincomycin is used. The Maxillofacial unit at the RBWH follows these guidelines with routine antibiotic use for every case.

Imaging

Evaluation of the orbitozygomatic fractures invariably involves the use of imaging. Most imaging modalities are available at the RBWH as it is the tertiary referral center for maxillofacial injury in Queensland, Australia. Imaging for orbitozygomatic fractures at the RBWH usually involves a computed tomographic (CT) scan at 2-mm intervals. These images can also be used for three-dimensional reconstruction and/or be used for construction of stereolithographic models. Plain films are also available but are not used preoperatively by this unit. Postoperative assessment, however, does include the use of plain films.

Management and Surgical Repair

Displaced orbitozygomatic fractures at the RBWH are repaired with open reduction and internal fixation soon after injury. When indicated, repair can be delayed temporarily for gross swelling to resolve or if life-threatening injuries are required to be attended to [

14]. In all cases, however, it is the Maxillofacial unit’s policy that orbitozygomatic fractures should be repaired within 2 weeks.

Common surgical approaches for reduction of orbitozygomatic fractures include the intraoral approach as described by Keen’s and the Gillies et al.’s temporal approach [

15,

16].

Other incisions commonly used for access to the orbitozygomatic skeleton by this unit include the upper blepharoplasty, subciliary, subtarsal, infraorbital, and transconjunctival approaches [

17,

18].

Complications

Posttraumatic orbitozygomatic complications include ocular injury, residual telecanthus, enophthalmos, diplopia, nerve paraesthesia, cosmetic deformities, problems with rigid fixation, and scarring [

19]. Orbitozygomatic fractures can result in significant globe displacement as the zygoma constitutes the anterolateral portion of the orbit. Minor ophthalmic injuries included subconjunctival hemorrhage, iris sphincter tear, and corneal abrasion (66.6%). Major ophthalmic injuries included ruptured globe and retinal hemorrhage (10%). Diplopia was noted in 16% of patients dropped to 2% in the 3-month postoperative period [

20]. Transient diplopia is commonly due to posttraumatic edema of periorbital tissues. Persistent diplopia is due to frank entrapment of ocular musculature, orbital adnexa, paralysis of the ocular musculature secondary to trauma, or nerve injury and occurred in 1.1 to 33% of cases, depending on the severity of the injury [

20,

21]. The proximity of the zygoma to the infraorbital canal and foramen is the main factor for initial and persistent paraesthesia of the infraorbital nerve. Zingg et al. concluded that 23.9% of their series of 1,025 patients suffered from persistent paresthesia of the infraorbital nerve [

22].

The most commonly reported complications included inaccurate reduction causing minor asymmetry (7.7%), major asymmetry (4.9%) [

5], ectropion (14%), diplopia, and epiphora [

23]. The incidence of postoperative complications differed between research papers [

2,

3,

4,

5,

6]. Treatment included local wound care, antimicrobial application, and oral antibiotics [

24]. Infection most often occurred when the intraoral approach was used and mainly in patients with poor oral hygiene [

23].

According to Zingg et al., significant facial asymmetry requiring surgical revision occurred in 3 to 4% of patients [

22]. Poor choice of sutures and suturing technique resulted in infection and keloid formation leading to poor cosmesis. An unrecorded incidence of maxillary sinusitis was noted postoperatively, which was prevented through postoperative sinus precautions and the use of antibiotics, nasal decongestants, and sprays [

19].

Longer-term complications included migration of the plate due to bone resorption (2.3%) and a “cold feeling” associated with the titanium mini-plates during the cooler months of the year (1.4%) [

24].

Because of strict surgical protocols, the complication rate of this particular injury subtype managed at the RBWH Maxillofacial unit was exceptionally low. Antibiotic usage is, however, routine and may be a factor in the low infection rate.

Conclusion

The RBWH treats a significant number of orbitozygomatic fractures. The complication rate is very low at 1.9%. It should be noted that of the three complications, all returned to theater where the surgical problem was corrected without further consequence. The infection rate is nil. This could be attributed to the use of strict surgical protocols and prophylactic antibiotic use. It should be noted that all cases of orbitozygomatic fractures are operated on in this institution with direct consultant supervision. Audits are held weekly and follow-up protocols with patient recall is strict.

It is considered that there is a general overuse of antibiotics in medicine. Surgical repair of orbitozygomatic fractures may in fact be one surgical procedure that does not require antibiotics. It is recommended that further studies be considered to review the use of prophylactic antibiotics in the management of this injury. The authors have considered that because the infection rate is so low, in this and other papers, thought may be given to modifying the antibiotic protocol by limiting its use to surgical prophylaxis only and not extending it beyond the 24 h postoperative period.