Rigid internal fixation (RIF) revolutionized the management of craniomaxillofacial trauma. Convalescence was simplified and made more pleasant. The course of treatment was shortened and outcomes were improved. In no area is this more evident than in the management of atrophic mandibular fractures. These injuries have always been difficult to manage in any setting. The patients are often elderly and infirm. The bone has little osteogenic potential and thus diminished healing capacity [

1,

2]. There is opposing muscle pull from the elevators and depressors of the mandible, which tends to place tension across the facture, which then displaces it. When reduced, there is minimal bone height to achieve adequate buttressing; this puts much stress on any internal fixation device.

Traditional forms of treatment (wiring in dentures or splints), in addition to not achieving union in the proper place, created a host of comorbidities themselves in the form of infection, discomfort, and so on. Indeed, maxillomandibular fixation (MMF) in elderly, infirm patients often resulted in pulmonary complications and death. Skeletal pin fixation, although effective, was cumbersome and ungainly and not well tolerated by the patient.

Open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) with wire, usually supplemented with some form of MMF or external fixation, often resulted in non- or malunion. The literature is replete with reports of poor outcomes with these difficult injuries [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Rigid fixation initially offered the prospect of repair with more predictably favorable outcomes as well as a more comfortable and less awkward convalescence. As more and more experience was gained, it became evident that some forms of rigid internal fixation give predictably more favorable outcomes than others. We share our experience managing the complications of failure with miniplates used in the management of atrophic edentulous mandibular fractures.

Miniplate fixation of atrophic mandibular fractures superficially looks to be a fairly ideal method of management. They are small, easily adapted to the bone, and have small screws that seem to lend themselves to placement in small, thin fragments. Extensive exposure is not necessary, and they can often be placed transorally. In short, they are easier to apply than even transosseous wire fixation.

In other types of mandibular fractures where the possibility of load sharing exists, miniplates are most useful with predictably good outcomes [

8,

9,

10,

11]. Indeed, in angle fractures that lend themselves to this load sharing, the single transoral miniplate placed as a “tension band” results in the lowest morbidity of any form of treatment [

12]. This is hardly the case in atrophic fractures where there is little surface area at the fracture site for load sharing. In these cases, the plate and screw construct must take up the load, and miniplates are not up to the task. The mandible is subject to flexion or “wish boning” when opening and closing or even during swallowing [

13]. This becomes more pronounced in the edentulous mandible. This “wish boning” quickly hardens and fractures miniplates or pulls the small screws from the bone; both complications result in failure. Both single and double miniplates as well as the heavier 2.0 locking plate are subject to this failure [

14].

We present our results with retreatment of eight miniplate failures in atrophic mandibular fractures. Although this hardly is a comparative study, it does represent our total experience in managing miniplate fixation of atrophic mandibular fractures, all of which resulted in subsequent failure. We also submit that retreatment should consist of an aggressive reconstruction with load-bearing osteosynthesis as well as primary bone grafting of the atrophic fracture sites [

15,

16]. This is true mandibular reconstruction according to AO/ASIF principles [

17,

18,

19]. If the miniplates have been placed bilaterally for bilateral fractures and only one side failed, we do not wait for the other side to fail. We go ahead and reconstruct both sides simultaneously.

Because the best bone stock is in the angle and symphysis, this is where the reconstruction-type plate should be anchored with bicortical screws—at least three on each side of the fracture. In bilateral fractures, a single plate facilitates anterior fixation in the symphysis because it may be difficult to get six screws in place if two plates were used. Indeed, if one side needs to be later removed, or to facilitate removal of the entire plate, it can always be cut into two pieces with a high-speed bur. The plate itself must be big enough to withstand continued flexion until union occurs. In our hands, this means a reconstruction plate or currently a locking reconstruction plate. In these cases, the plate is often larger than the bone in the markedly atrophic saddle areas of the mandibular bodies [

20,

21]. The bone at the fracture site is completely cortical, with a porcelain characteristic. This bone has little if any osteogenic potential. As such, these areas require grafting with fresh autogenous bone marrow to facilitate union. This is based on our early experience, in which nonunions were noted when plate removal was attempted. Reconstruction was not simply limited to hardware removal and coapting a larger plate; we found that bone grafting was necessary to augment bony healing and restore bony continuity, thus yielding a predictable outcome. Likewise, defect areas require grafting because true RIF will not allow micromovement and callous generation, facilitating union.

We have followed this protocol for primary management of atrophic mandibular fractures since 1989. We have aggressively managed them with wide-exposure RIF with a reconstruction plate or locking reconstruction plate utilizing bicortical screws in the symphysis and angles and primary grafting of the fractures with autogenous particulate marrow from the tibia or iliac crest. All patients in our series (14) went on to union and were restored to preinjury function in a single operation [

16].

The same obviously cannot be said for attempted management of these difficult injuries with miniplates. Although we have not personally used this form of treatment, other than for temporary immobilization to hold the reduction while a reconstruction or locking reconstruction plate is placed, we have managed the complications of eight cases of miniplate fixation done elsewhere. Of the eight patients, the age range was 36 to 81 years. Six presented with bilateral fractures of the mandibular body and two with unilateral fractures also in the mandibular body. All fractures were noted in the areas with the most significant atrophy. These patients initially presented to us with complaints related to plate failure including mobility, infection, and/or drainage. All fixation failures occurred at the fracture sites regardless of whether or not they were treated with both single or dual 2.0 miniplates or newer 2.0 heavy-locking miniplates. Screw fracture and/or loosening was also noted in most cases. Of particular note, there were two cases where miniplate fixation was attempted three times before the patient was referred to us for our form of definitive care. All failures in our series occurred within 3 weeks of initial reduction and fixation, some as early as 2 days postoperatively. The treatment plan for all was the same: fractures were primarily reconstructed as outlined with reconstruction plates or locking reconstruction plates, and autogenous bone grafts from either tibia or iliac crest were placed at the time of surgery. All went on to union without complication. We present two cases that are illustrative of the eight.

Case Reports

Case 1

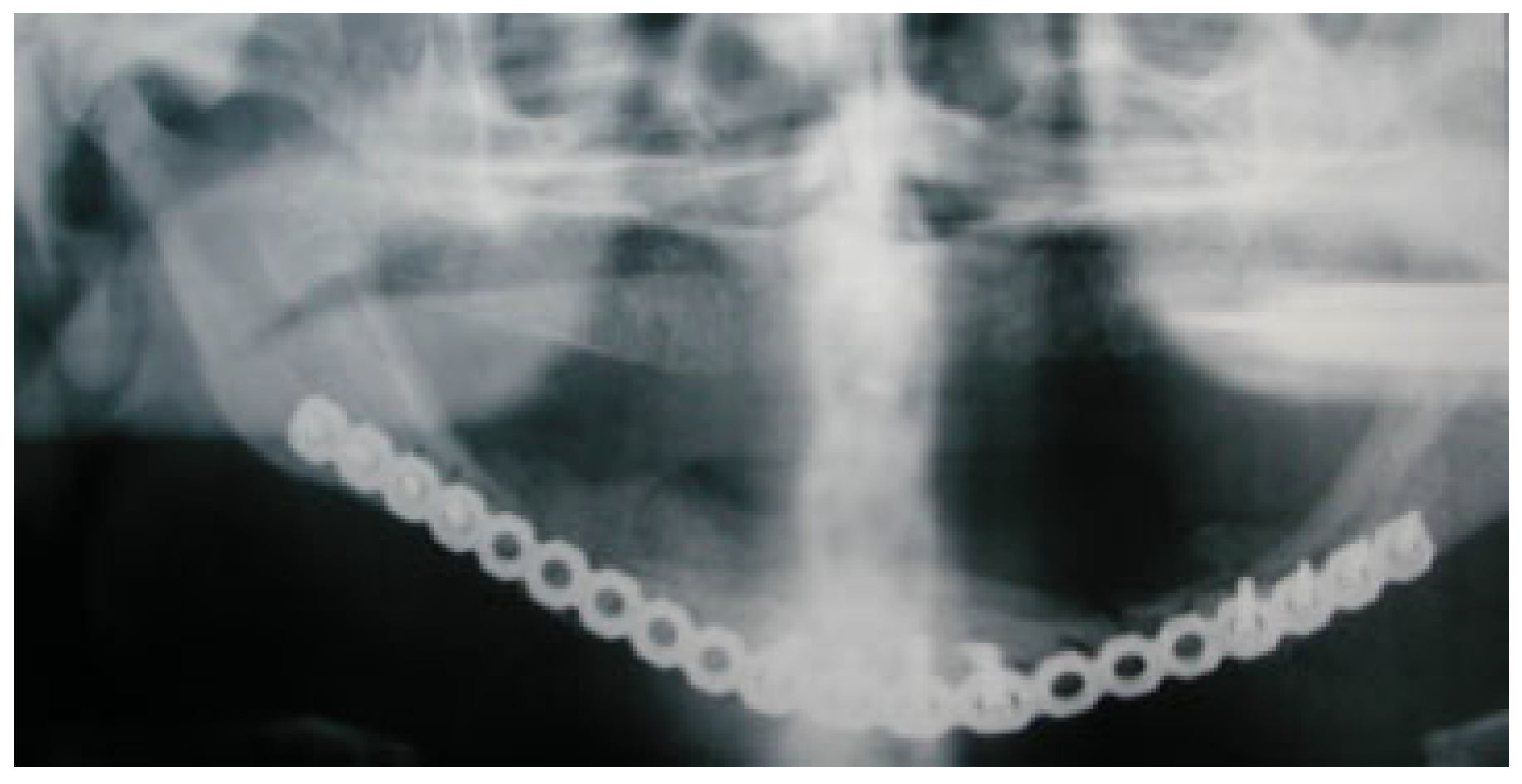

A 55-year-old man was referred from an outside hospital to the University of Louisville oral and maxillofacial clinic; his chief complaint was inability to eat along with mandibular mobility. His history was consistent with a previous attempt at ORIF of a bilateral mandibular fracture. A panoramic radiograph was obtained, showing failed miniplate fixation of an atrophic right mandibular body (

Figure 1). The left mandibular body demonstrated the same fixation with the hardware still intact. Previous panoramic X-rays were obtained from the referring surgeon and demonstrated intact hardware postoperatively (

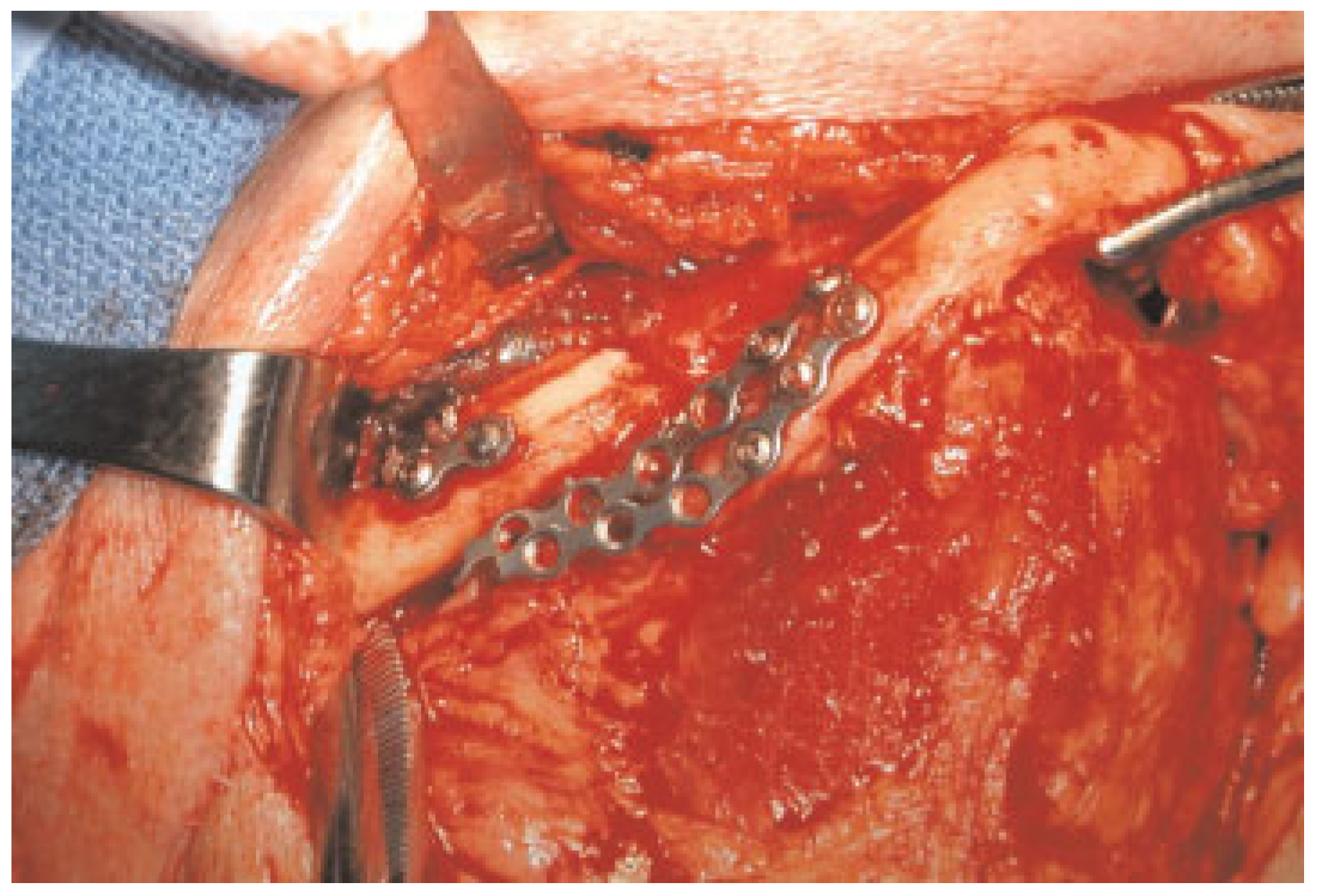

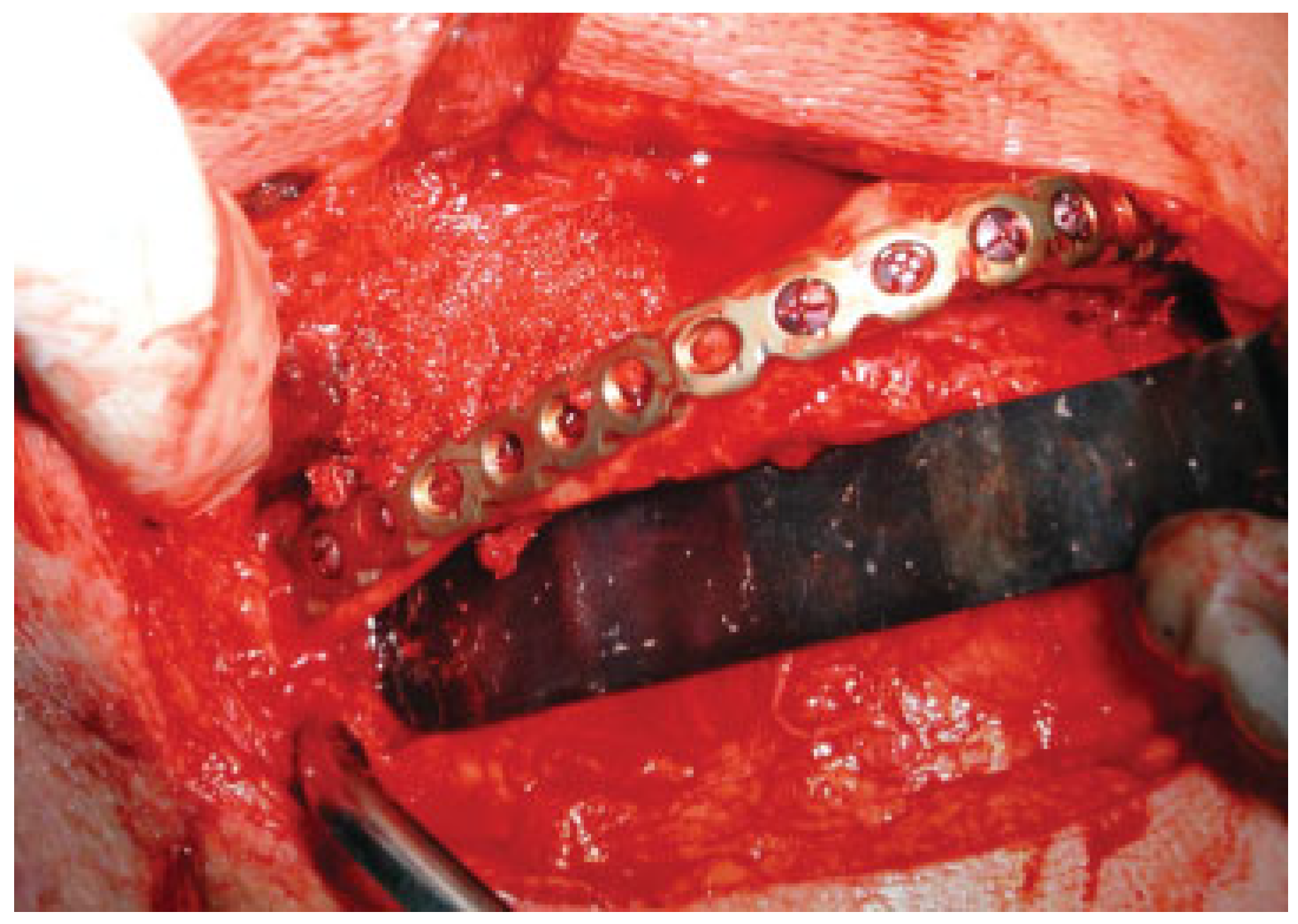

Figure 2). These findings were explained to the patient, and a plan was made for definitive treatment to remove the hardware and to reconstruct using an extraoral approach with a load-bearing plate in conjunction with autogenous bone grafting. Intraoperatively, an obvious failure of the two miniplates on the right mandibular body was seen (

Figure 3) with the left-sided fixation construct still intact (

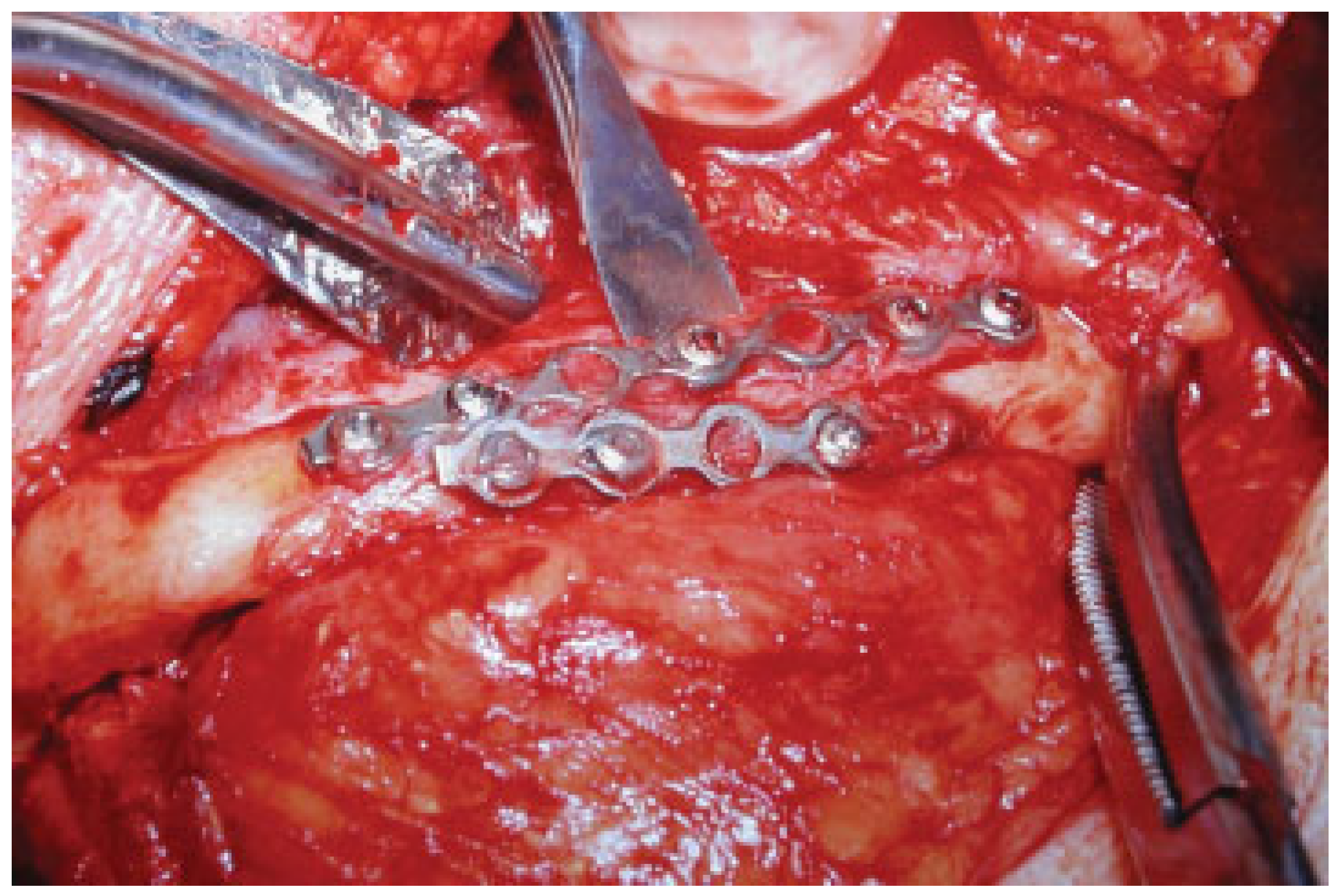

Figure 4). The hardware was removed bilaterally with a plan to reconstruct the entire atrophic mandible before the left side failed as well. A template was fashioned for the reconstruction plate (

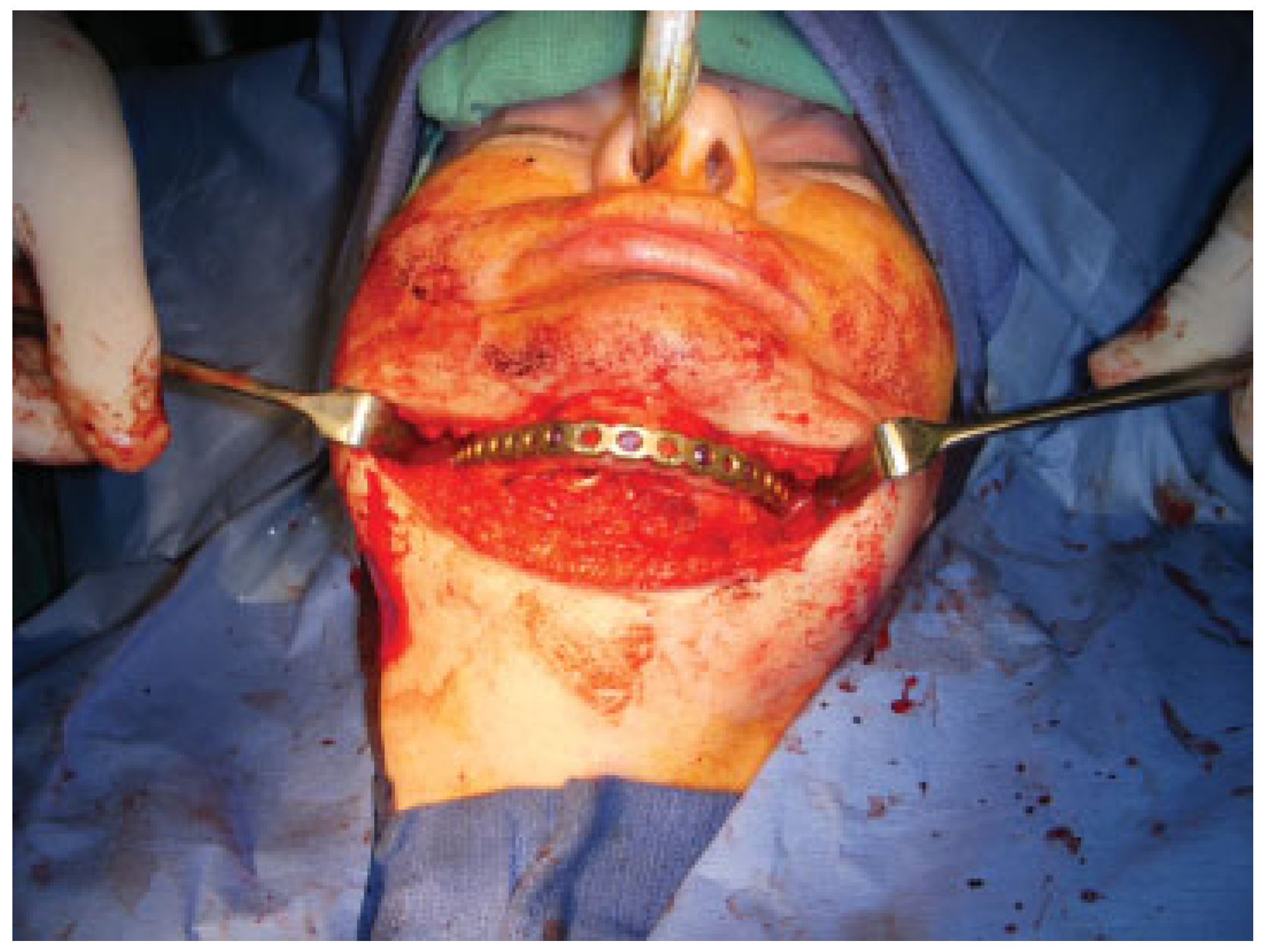

Figure 5) with a simultaneous tibial bone graft harvest. A locking reconstruction plate was secured to the mandibular angles bilaterally as well as the symphysis (

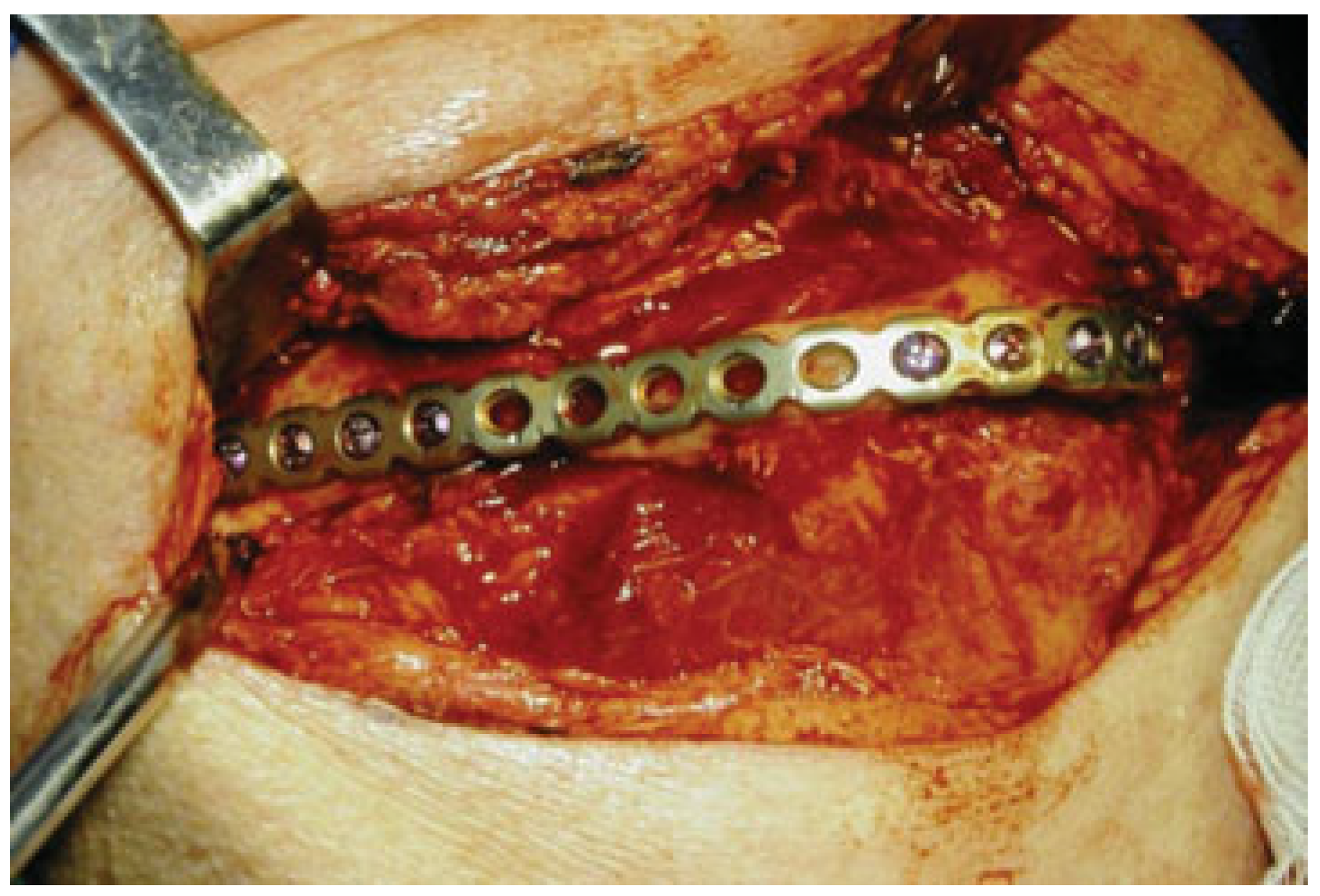

Figure 6). The autogenous bone graft was then placed (

Figure 7), and the incisions were closed. Postoperative panoramic X-rays showed excellent fracture reduction with ample bone graft in place (

Figure 8). The patient went on to recover with no functional deficits.

Case 2

A 36-year-old woman was referred to our institution for treatment from another surgeon after two failed attempts at repairing a bilateral atrophic edentulous mandibular fracture. The first attempt at fixation was with miniplates placed bilaterally after reducing the fractures. These failed within 3 days. The second attempt was fixation with a larger locking 2.0 plate placed bilaterally along the lateral border of the mandible, with a second miniplate placed along the inferior border (

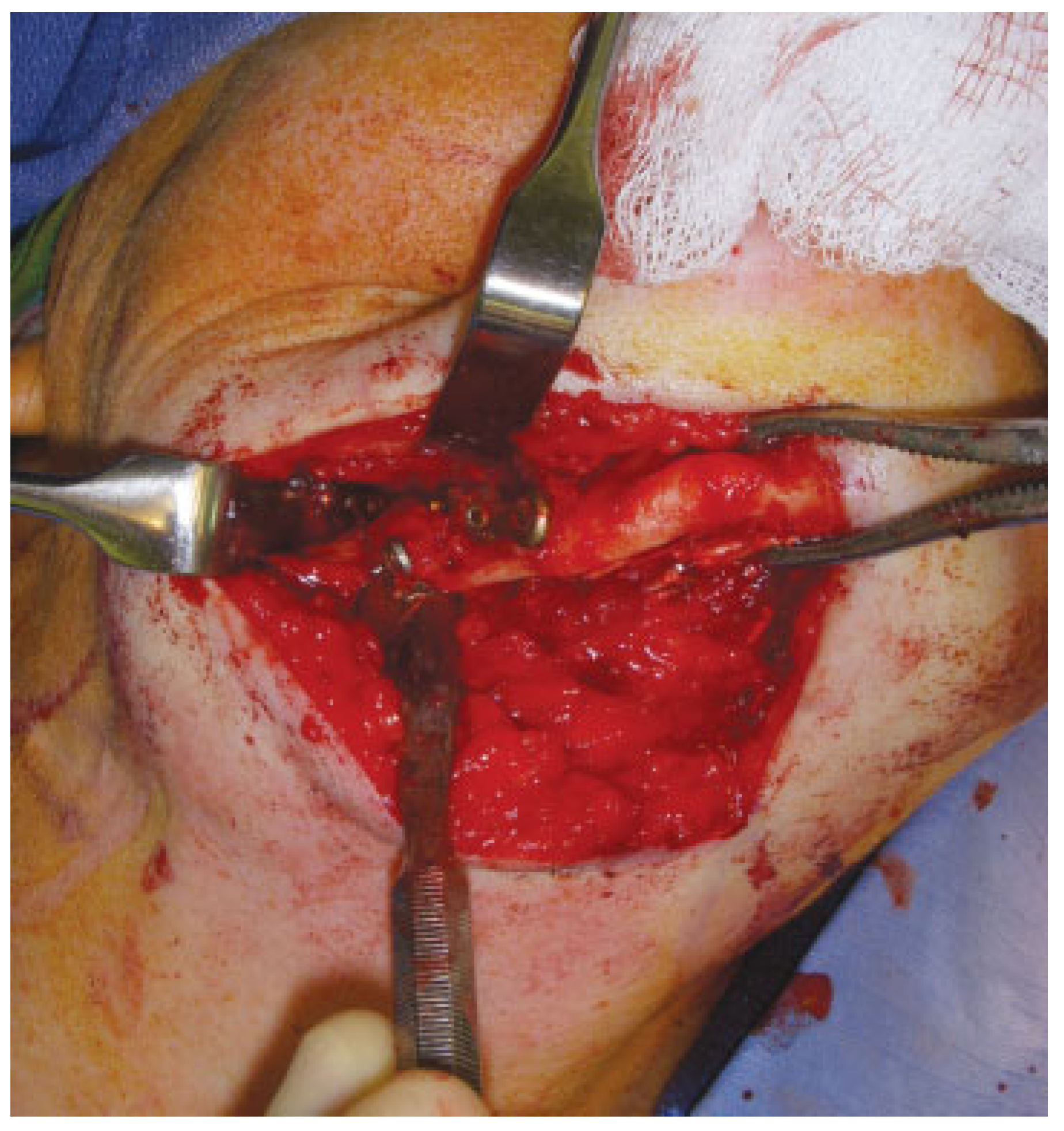

Figure 9). This construct failed within a matter of weeks. A plan was made to proceed with a definitive reconstruction using a large locking reconstruction plate with autogenous bone grafting as previously described. Intraoperatively, it was noted that the fixation along the right mandibular body was the point of failure (

Figure 10). A locking reconstruction plate was fashioned and secured to the mandibular angles bilaterally as well as to the symphysis (

Figure 11). The graft was then placed (

Figure 12) and the incision was closed. Postoperative computed tomography scans showed excellent reduction and plate adaptation with favorable bone graft placement (

Figure 13). The patient’s postoperative course was uncomplicated.

Discussion

We certainly recognize the difficulty with this form of treatment. It requires a center with an extensive armamentarium and skilled team to accomplish. This may not always be available in some of the more remote areas. Yet we hope to make the point that miniplate fixation should only be looked upon as temporarily immobilization in these particular difficult injuries. We also acknowledge that even though our experience has yielded very favorable results for treating miniplate failure, there is no comparative group to which we can scrutinize our long-term results. We feel that at this time, our approach following AO/ASIF principles using a load-bearing plate, augmenting bony healing with nonvascular autogenous bone, in conjunction with anatomic reduction, yields the most predictable result in this patient population. Further prospective, randomized study may be performed, yet the relative paucity of these fractures, compounded with patient’s comorbid medical conditions at the time of injury, necessitates treatment using methods known to be successful, not methods hoped to be successful.