Traumatic amputation or laceration of the auricle is a periodic occurrence often caused by human and canine bite injuries, followed by accidents. [

1] Reattachment and microsurgical anastomosis of the vessels are considered state of the art. Reattachment without venous anastomosis can be justified due to the rapid revascularization, the capacity of the auricle to tolerate hypoxia, and the efficacy of treating venous stasis by leeching. Reattachment without arterial anastomosis is usually successful in partial lacerations, where the irrigation via the capillaries of the remaining soft tissue bridge often is sufficient. In amputations, reattachment as a composite graft without anastomosis does not appear to be promising, yet it is a common task—‘‘utaliquid fiat’’—in nonspecialized hospitals. Due to the widespread unfamiliarity with leech therapy, some auricles that might have had sufficient capillary input are lost due to venous stasis.

Leech therapy generally is contraindicated in anticoagulated patients. [

2] Nevertheless, we will encounter this condition more often in the next years due to the demographic evolution. We present a case of successful reattachment of a partial amputation of the upper left auricle followed by leech therapy in a patient with concomitant anticoagulation, and we review the different treatment possibilities.

Case Report

The patient was a white male, 74-years-old, with a history of pulmonary embolism in 1999 due to a deep venous thrombosis in the right leg. At the time of the accident, he was under concomitant anticoagulation therapy with warfarin (alternating 5 mg/d and 3.75 mg/d, international normalized ratio 2 to 3).

By accidentally colliding with a radiator, he suffered an amputation of the upper third of his left auricle. With the amputated part wrapped in a napkin, the patient presented at the local hospital, where the staff of the emergency room reattached the amputated part 3 hours later as a composite flap without microsurgical anastomosis.

The patient received levofloxacin 500 mg and was discharged with the recommendation to present to a plastic surgeon for follow-up. The following day, he presented to our outpatient clinic. The reattached part presented an anemic aspect and, due to the time passed, further microsurgical measures were discarded. The patient was prescribed amoxicillin with clavulanic acid 1 g/8 h and was asked to continue his habitual prophylaxis with warfarin.

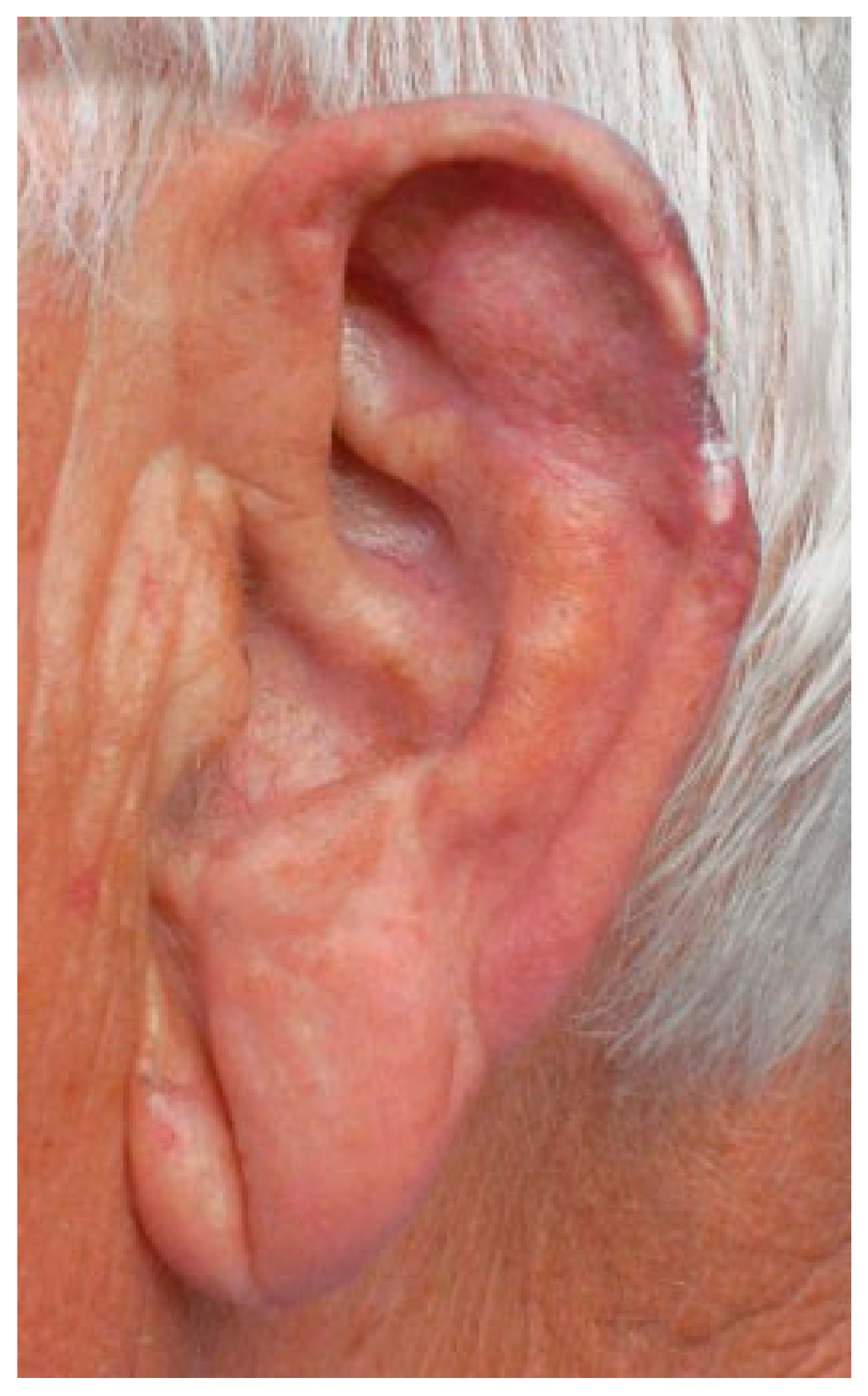

The next day (some 35 hours after the accident), the reattached part presented a livid coloring, indicative of venous congestion. Stab incisions produced scarce quantities of blood of dark color (

Figure 1).

The patient was admitted and leech therapy was initiated (

Hirudo medicinalis, Biopharm Leeches

TM, Hendy, South Wales, UK). Two leeches were applied and remained until reaching a volume indicative of sufficient ingestion (~20 minutes) before withdrawal. The decongestive effect was visible in the course of application (

Figure 2). During the following 48 hours, two leeches were applied every 8 hours. Posttreatment care to avoid early closure of the bites and to favor passive bleeding consisted of applying gauzes soaked in warm saline solution. The warfarin treatment was not suspended or substituted. Upon spontaneous bleeding and not showing signs of congestion, leeching was suspended temporarily during the third day. On the fourth day, epidermolysis began, forming a blister (

Figure 3). As it was accompanied by signs of congestion, leeching was reinitiated once every 24 hours, to the ninth day. The patient was dismissed that day showing partial necrosis of the epidermis of the reattached part (

Figure 4). The hemogram confirmed a light anemia (red corpuscles 3.69 ċ 10

12/L, hemoglobin 12.00 g/dL, hematocrit 35.2%) that did not require transfusion.

The patient was seen weekly and the auricle was almost completely epithelialized 44 days after the amputation (

Figure 5). Three months later, 90% of the amputated part had survived and the patient was satisfied with the final result (

Figure 6).

Discussion

Surgical Management

Reattachment of amputated parts has always been a desire throughout human history. The New Testament (Lucas 22:47) relates the reattachment of Malchus’ auricle by Jesus after its amputation by St. Peter. [

3] In the medical literature, the first reattachment of an auricle after an amputation as a result of a horse bite was described by Brown 1898. [

4] In 1966, Buncke and Schulz [

5] described the microsurgical technique of reattaching auricles in rabbits, and Pennington et al. described the first successful reattachment with microsurgery in humans in 1980. [

6]

The auricle primarily consists of skin and cartilage, which, due to their low metabolism, show a higher resistance toward ischemia. Times of ischemia of 10, 18, and up to 33 hours have been described, [

3,

7,

8] a fact that plays an important role in survival as a composite flap.

Small defects of the auricle are esthetically well treated by performing a reductive otoplasty if localization and size permit it. In cases of larger lacerations or amputations, it is recommended to reattach the avulsed part. [

9,

10] This also applies to bite injuries, disregarding the usual practice not to perform primary closure due to contamination and damage of the wound margins.

The reattachment with microsurgical connection of the blood vessels is state of the art. [

11] Nevertheless, it is a challenging task to find and connect the auricular vessels due to their minuscule size (

Figure 7). It is not recommended to perform excessive searches for vessels to avoid further damage to the capillary bed. Due to the good blood supply of the auricle, it is sufficient to connect one single artery. [

12]

Most problems are caused by the venous drainage. Some authors recommend multiple anastomosis, [

13] and others describe the difficulties to find adequate veins. [

2,

7,

11,

14,

15] Concannon and Puckett [

16] and De Chalain and Jones [

17] even discourage performing venous microanastomosis in difficult cases due to the good results when treating venous congestion adequately.

If it is impossible to perform microsurgical anastomosis, the reattachment without it, like a composed flap, is recommended. [

9,

12,

16] It has a good prognosis in cases of partial lacerations due the ample ability of the remaining tissue bridge to nourish the auricle. [

12] In amputations, reintegration as a composite flap is indicated only if microsurgical techniques are unavailable. It has advantages like its simplicity, short duration, and few additional scars, facilitating secondary reconstruction in case of failure. [

12] The risk of failure is influenced by the size of the amputation. In surgically designed transplants from the auricle, a composite graft up to 15 mm has a success rate of 90%, and grafts more than 15 mm fail in 50%. [

18] In traumatic amputations, nevertheless, the laceration of the wound margins might lead to difficulties in revascularization and thus to minor success rates.

Contused and necrotic tissue should be debrided because revascularization—beginning in the subdermal plexus—cannot be effective within the necessary time if a barrier of compromised or necrotic tissue has to be passed. It may even be beneficial for revascularization to amplify the surface of nonepithelialized tissue by resection of retroauricular skin. [

9,

14,

16]

The metabolic needs can be lowered by cooling, which is recommended in transplants. [

19] Yet in cases of reduced arterial or venous flow, warm dressings are used to encourage vasodilatation.

An alternative to microsurgical reconstruction is the dermabrasion of the amputated part, its reattachment, and its conservation in a retroauricular subcutaneous pouch. [

20,

21,

22] This has proven successful in partial amputations from one-third to two-thirds of the auricle, [

7] although the esthetic result might be deficient as the cartilage can suffer morphological changes such as ossification and fibrous degeneration. [

23]

It is advised to carefully evaluate the indication of nonmicrosurgical techniques and to consider even a more time-consuming transport to a center with microsurgical experience. [

1] The treatment should be considered ‘‘planned urgent’’ rather than as an emergency surgery. [

8]

Venous Congestion

Venous congestion in reattached auricles is such a common situation that we have to accept it as being an accompanying symptom rather than seeing it as a complication. [

12] A meta-analysis found venous problems in 10 of 14 cases with arterial and venous microsurgical anastomosis. Eight cases were treated appropriately (six with leeches and two with external decompression) and rescued. A case without treatment and another that was treated too late lost their auricle. [

16]

In cases of venous stasis, the question is not whether to introduce leeching and anticoagulation, but rather when to do so. [

11]

Leech Therapy

At the present time, in many hospitals leech therapy has not yet become part of the standard armament of treating venous stasis. The lack of awareness of its possibilities and the concern of provoking an antediluvian image hinder its nationwide introduction, leading to the loss of some reattached auricles.

Leeching has a long history and was very popular in medieval times, whereas from the 19th century to the last quarter of the 20th century, few descriptions are found. [

24] With the advances in plastic and reconstructive surgery, leeches again began to play an important therapeutic role in the 1960s, mainly in cases of venous stasis in flaps.

The

Hirudo medicinalis has three jaws with 60 rigid, thin, sharp teeth, each of which has a secretory opening. [

25] The secretions consist of anticoagulants such as hirudin (a potent inhibitor of thrombin), antiaggregating substances like calin, vasoactive substances like histamine, proteases such as collagenases and hyaluronidases, and anesthetics. [

2,

26] This cocktail not only facilitates the puncture of the skin and ingestion of blood but also increases the capillary flow by vasodilatation and thrombolysis and prolongs passive bleeding after withdrawal of the leech. [

24,

27]

A study with skin flaps in pigs found that between 1 and 5 mL of blood was ingested by one leech, with an average of 2.45 mL. The passive bleeding after withdrawal of the leech lasted up to more than 4 hours. [

26] In our anticoagulated patient, the quantities seemed to have been higher and the times of passive bleeding under application of warm saline-soaked gauzes were longer. Additionally, the size of the area of reperfusion was evaluated. [

26] A 16-mm average diameter of increased perfusion was measured. Outside that area, the effect was smaller, making it advisable to apply one leech every 15 to 20 mm.

Leeching should continue until revascularization is sufficient, which takes about a week (4 to 10 days). [

14,

26] In our case, it took 9 days, though the suspension of leeching during the third day and the low frequency of application possibly prolonged the time necessary for revascularization.

Control of the therapeutic effect on the ear’s perfusion is made clinically, observing color, temperature, and capillary refill. Attempts to objectify the perfusion by using a dye (fluorescein) have been described. [

11] Yet, because visual inspection is a very simple, reliable, and effective way to control the efficacy of leeching, other more laborious methods are preferably applied when objectivity is required for scientific studies.

The drawbacks of leeching are the time and the personnel needed to perform leech therapy. [

26] In difficult cases, it may be necessary to apply leeches every 4 hours at first, reducing frequency during the course. In our case, nurses volunteered to apply and monitor the leeches. In other hospitals, the nursing staff does not consider leeching to be part of their duty. An article in

The American Journal of Nursing, on the other hand, states that ‘‘nurses may be expected to participate in this therapy’’ and offers guidelines for the nursing staff. [

28] Given the problems of time and staff, delegating the monitoring of the leech to the family of the patient might be considered, in cases of good acceptance and interest.

Complications of leeching are migration of the leech to healthy tissue, infection, and hemorrhage. [

2] The tendency of the leech to search for healthier tissue and its instinct to hide after feeding require vigilance during the whole time of application.

Aeromonas hydrophila, a gramnegative germ located in the gut of the leech, is the main cause of infections. Antibiotic prophylaxis must be given. Several antibiotics are recommended: third-generation cephalosporins, aminoglycosides, tetracyclines, and ciprofloxacin. [

2,

29]

Hemorrhage and Anticoagulation

The loss of blood can reach a pathological value. Anticoagulated patients or patients with coagulopathies are usually not considered to be candidates for leeching. [

2] However, recommendations are contradictory: on one hand, it is advised not to treat these patients, and on the other hand, it is widely recommended to prescribe anticoagulants during leeching in healthy patients. [

7,

10,

11,

12,

30] Our patient was under anticoagulation with warfarin (international normalized ratio 2.2), and as the area of leeching was easily accessible for control and as less bleeding has to be expected in composite flaps because no arterial input is present, we decided to start leeching and continue his medication.

A control blood count on the ninth day showed mild anemia, but no blood transfusion was required. Steffen et al. [

1] reviewed publications of 37 cases of microsurgical reattachment of the auricle and found that 20 cases (54%) required blood transfusions, demonstrating the risk of critical blood loss if an arterial anastomosis is present. The risk of having to receive a transfusion has to be discussed with the patient before leeching. A patient who refuses transfusion (for religious reasons, for example) might not be a candidate for leech therapy.

Other contraindications are arterial insufficiency, immune system disorders, and allergy. [

2]

There is consensus in the literature that the patient should be anticoagulated systemically in cases of ear reattachment. But there is no consensus on what type of anticoagulant to use. Heparin, aspirin, warfarin, prostaglandin E, dextrans, and combinations have been used. [

7,

8,

10,

11,

12,

30] Because our patient was taking warfarin for 10 years, we decided he should continue with his usual dose without adding other anticoagulants or antiaggregants. Curiously, anticoagulation is not part of the protocol in composite grafts from the auricle (e.g., to the ala of the nose). Anticoagulation should even be discontinued preoperatively because of the risk of hematoma. [

19]

There are few alternatives if leeching is not possible or does not show the desired result. Various skin incisions and injections of heparin have been tried or a stab incision in the lobe with a gauze drainage, but the consensus is that leeching is the preferred method. [

2,

12,

15] Mechanical devices have been tested to substitute leeches. [

31] The amount of blood drained was superior of that ingested by leeches (sevenfold), but no studies have been published to date showing their clinical usefulness.

Conclusion

The case presented is singular because of its circumstances. The patient was correctly treated surgically in another hospital but discharged without further consideration of possible complications. He presented to our clinic and with a delay of 36 hours from injury, we started leech therapy. Supposedly, the patient’s anticoagulant therapy with warfarin could have played an important role in the survival of the amputated part during the first 36 hours without leech therapy, preventing capillary thrombosis and in consequence facilitating the minimal oxygenation necessary. Leeching was performed during 9 days and resulted in a good outcome of 90% survival of the amputation. An increased frequency of leeching might have prevented epidermolysis and necrosis of 10% of the amputated part.

However, leech therapy is timeand staff-consuming, and in many hospitals a controversy exists between doctors and nurses about who should be assigned. This, the lack of knowledge about its beneficial effects, and the fear of provoking a medieval impression—especially among nonmedical decision makers—still prevents the use of leeches in all major hospitals. Nonetheless, it is important to consider some disadvantages of leech therapy, such as prolonged hospital stay, bleeding with the possible need for blood transfusion, and a certain risk of infection.

The demographic evolution will lead to more and more patients with ongoing anticoagulation who might need leeching. That should make us reconsider that in locations that can be easily controlled, an ongoing anticoagulation therapy should be no contraindication for leech therapy in reattached amputations. Caution is advised where patent arterial anastomoses are present.