Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: Management and Outcomes in a Tertiary Maxillofacial Surgery Unit

Abstract

1. Introduction

- Acute Osteomyelitis (AO)—duration less than 4 weeks.

- Secondary Chronic Osteomyelitis (SCO)—duration of more than 4 weeks, often evolving from an acute episode, marked by milder symptoms.

- Primary Chronic Osteomyelitis (PCO)—a non-suppurative, idiopathic chronic inflammation, typically presenting with intermittent flare-ups intersected with symptom-free periods.

Objectives

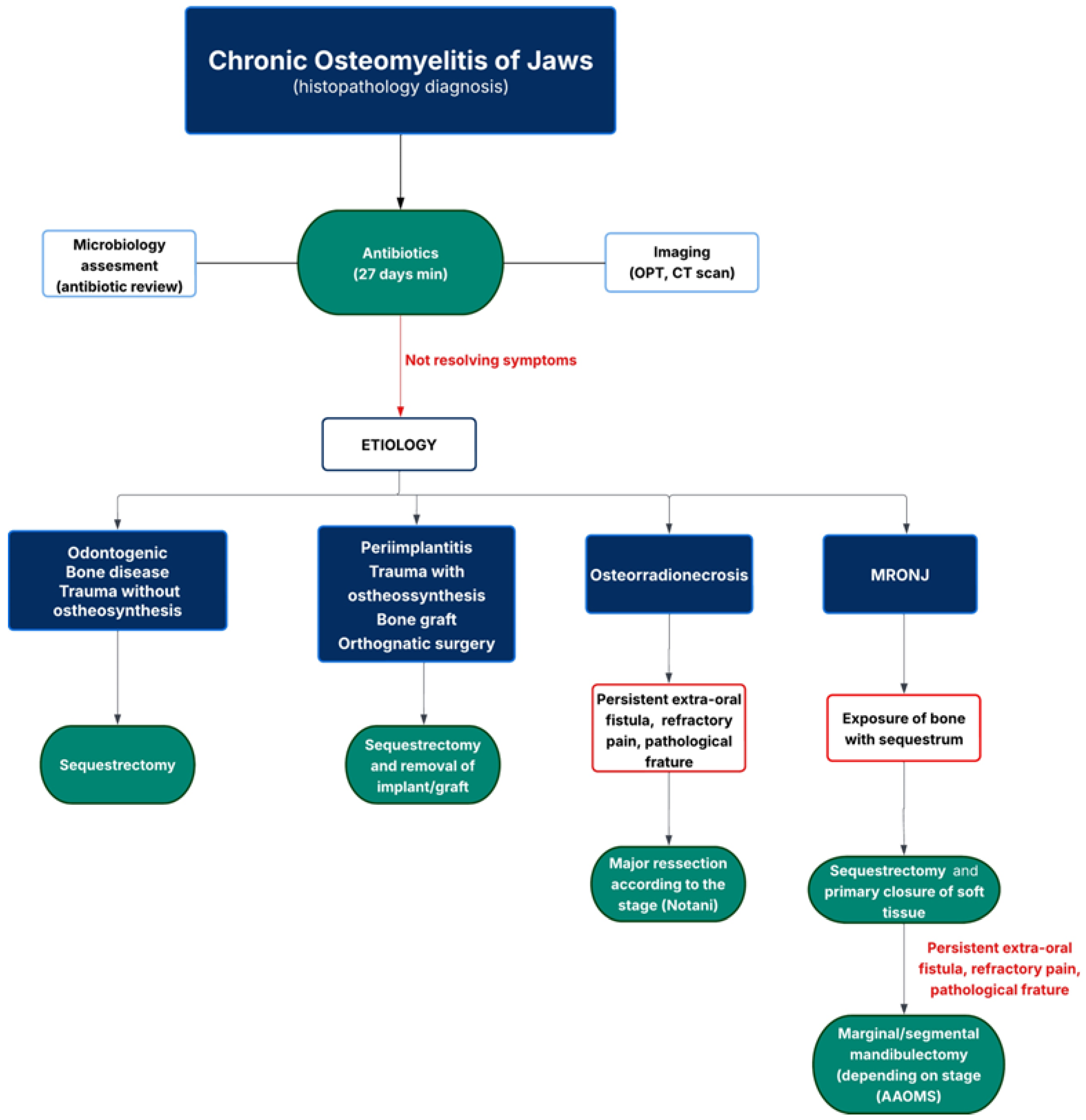

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection

2.4. Data Analysis

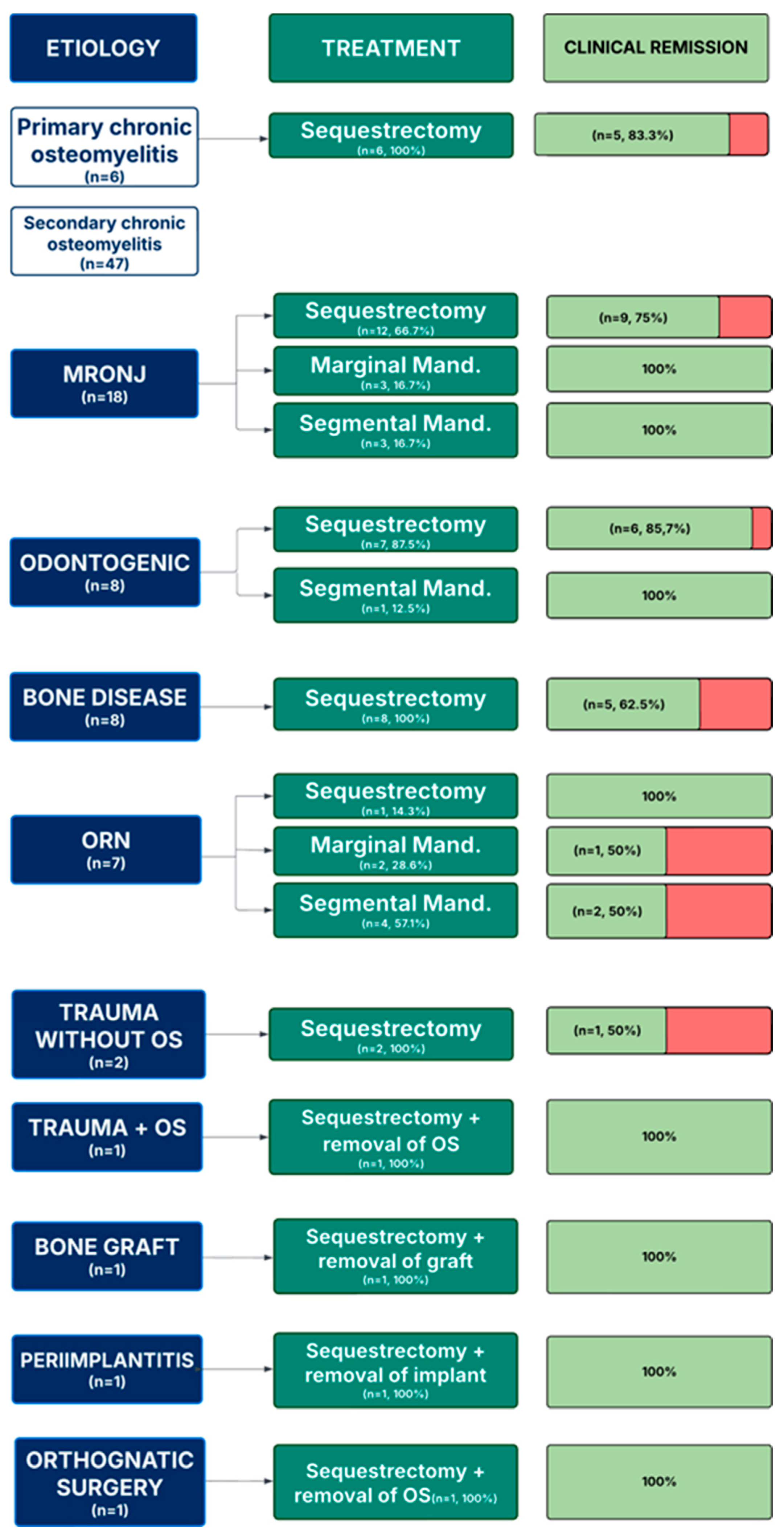

3. Results

3.1. Demographic and Clinical

3.2. Management

3.2.1. Diagnosis

3.2.2. Treatment

4. Discussion and Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Andre, C.V.; Khonsari, R.H.; Ernenwein, D.; Goudot, P.; Ruhin, B. Osteomyelitis of the jaws: A retrospective series of 40 patients. J. Stomatol. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2017, 118, 261–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltensperger, M.M.; Eyrich, G.K.H. Osteomyelitis of the Jaws, 1st ed.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2009; pp. 5–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koorbusch, G.F.; Deatherage, J.R.; Curé, J.K. How Can We Diagnose and Treat Osteomyelitis of the Jaws as Early as Possible? Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2011, 23, 557–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coviello, V.; Stevens, M.R. Contemporary Concepts in the Treatment of Chronic Osteomyelitis. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2007, 19, 523–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moratin, J.; Freudlsperger, C.; Metzger, K.; Braß, C.; Berger, M.; Engel, M.; Hoffmann, J.; Ristow, O. Development of osteomyelitis following dental abscesses-influence of therapy and comorbidities. Clin. Oral Vestig. 2021, 25, 1395–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koorbusch, G.F.; Fotos, P.; Gollc, K.T. Retrospective Assessment of Osteomyelitis Etiology, Demographics, Risk Factors, and Management in 35 Cases. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. 1992, 74, 149–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peravali, R.K.; Jayade, B.; Joshi, A.; Shirganvi, M.; Bhasker Rao, C.; Gopalkrishnan, K. Osteomyelitis of Maxilla in Poorly Controlled Diabetics in a Rural Indian Population. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2012, 11, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baur, D.A.; Altay, M.A.; Flores-Hidalgo, A.; Ort, Y.; Quereshy, F.A. Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Mandible: Diagnosis and Management—An Institution’s Experience Over 7 Years. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2015, 73, 655–665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tani, M.; Hatano, K.; Yoshimura, A.; Horibe, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sassi, N.; Oka, T.; Okuda, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Uemura, T.; et al. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw during long-term prostate cancer management. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brunner, C.; Arvandi, M.; Marth, C.; Egle, D.; Baumgart, F.; Emmelheinz, M.; Walch, B.; Lercher, J.; Iannetti, C.; Wöll, E.; et al. Incidence of Medication-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in Patients with Breast Cancer During a 20-Year Follow-Up: A Population-Based Multicenter Retrospective Study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2024, 43, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sood, R.; Gamit, M.; Shah, N.; Mansuri, Y.; Naria, G. Maxillofacial Osteomyelitis in Immunocompromised Patients: A Demographic Retrospective Study. J. Maxillofac. Oral Surg. 2020, 19, 273–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuzayyen, A.; Elsaraj, S.M.; Agabawi, S. Osteomyelitis of the Jaw: A 10-Year Retrospective Analysis at a Tertiary Health Care Centre in Canada. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2024, 90, o6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- López-Carriches, C.; Mateos-Moreno, M.V.; Taheri, R.; Martínez, J.L.Q.; Madrigal-Martínez-Pereda, C. Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaw. Osteomyelitis. J. Clin. Exp. Dent. 2025, 17, e324–e328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balaban, S.; Shuster, A.; Kaplan, I.; Shlomi, B. Osteomyelitis of the jaws—Review of the literature and a case report. Refuat Hapeh Vehashinayim (1993) 2016, 33, 61–67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Portales Castillo, C.A.; Mousavian, M.; Peacock, Z.; Barshak, M.B. Jaw Osteomyelitis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2025, 39, 483–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adekeye, E.O.; Cornah, J. Osteomyelitis of the jaws: A review of 141 cases. Br. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 1985, 23, 24–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haeffs, T.H.; Scott, C.A.; Campbell, T.H.; Chen, Y.; August, M. Acute and Chronic Suppurative Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: A 10-Year Review and Assessment of Treatment Outcome. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018, 76, 2551–2558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, R.; Mills, C.; Burke, A.B.; Dhanireddy, S.; Beieler, A.; Dillon, J.K. Are Oral Antibiotics an Effective Alternative to Intravenous Antibiotics in Treatment of Osteomyelitis of the Jaw? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2021, 79, 1882–1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marschall, J.S.; Flint, R.L.; Kushner, G.M.; Alpert, B. Management of Mandibular Osteomyelitis With Segmental Resection, Nerve Preservation, and Immediate Reconstruction. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 77, 1490–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shuster, A.; Reiser, V.; Trejo, L.; Ianculovici, C.; Kleinman, S.; Kaplan, I. Comparison of the histopathological characteristics of osteomyelitis, medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw, and osteoradionecrosis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2019, 48, 17–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eyrich, G.K.; Baltensperger, M.M.; Bruder, E.; Graetz, K.W. Primary chronic osteomyelitis in childhood and adolescence: A retrospective analysis of 11 cases and review of the literature. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2003, 61, 561–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Total n = 53 | |

|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis, y | |

| Median (IQR) | 55 (5–90) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 25 (47.2) |

| Female | 28 (52.8) |

| Smoking Habits | |

| Yes | 12 (22.6) |

| No | 41 (77.4) |

| Alcohol habits | |

| Yes | 4 (7.5) |

| No | 49 (92.5) |

| Jaw affected | |

| Mandible | 45 (84.9) |

| Maxilla | 8 (15.1) |

| Both | 1 (1.9) |

| Immunocompromised condition | 22 (41.5) |

| Iatrogenic | 8 (36.3) |

| Cancer | 8 (36.3) |

| HIV | 1 (4.5) |

| Diabetes | 1 (4.5) |

| Rheumatoid Arthritis | 1 (4.5) |

| Tuberculosis | 1 (4.5) |

| Hepatic disease | 1 (4.5) |

| Renal disease | 1 (4.5) |

| Etiology | |

| Primary chronic osteomyelitis | 6 (11.3) |

| Secondary chronic osteomyelitis | 47 (88.7) |

| Medication related osteonecrosis of the jaw | 18 (38.3) |

| Osteoradionecrosis | 7 (14.8) |

| Bone disease | 8 (17) |

| Trauma | 3 (6.3) |

| Alveolar–dental | 8 (17) |

| Periimplantitis | 1 (2.1) |

| Bone graft | 1 (2.1) |

| Post orthognathic | 1 (2.1) |

| Total n = 53 | |

|---|---|

| Imaging | 49 (92.5) |

| CT scan | 46 (93.9) |

| OPG | 3 (6.1) |

| Bacteriological samples | |

| Performed | 25 (47.2) |

| Polymicrobial | 4 (16) |

| Germens isolated | 13 (52) |

| Actinomyces | 6 (46.2) |

| Streptococcus | 5 (38.5) |

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 2 (15.4) |

| Staphylococcus | 1 (7.7) |

| Citrobacter braakii | 1 (7.7) |

| Hafnia alvei | 1 (7.7) |

| Eikenella corrodens | 1 (7.7) |

| Proteus mirabilis | 1 (7.7) |

| Prevotella buccae | 1 (7.7) |

| Morganella morganii | 1 (7.7) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the AO Foundation. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Santos, P.; Moreira, C.; Gião, N.; Coelho, P.V. Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: Management and Outcomes in a Tertiary Maxillofacial Surgery Unit. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2025, 18, 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040043

Santos P, Moreira C, Gião N, Coelho PV. Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: Management and Outcomes in a Tertiary Maxillofacial Surgery Unit. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2025; 18(4):43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040043

Chicago/Turabian StyleSantos, Patrícia, Carolina Moreira, Nuno Gião, and Paulo Valejo Coelho. 2025. "Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: Management and Outcomes in a Tertiary Maxillofacial Surgery Unit" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 18, no. 4: 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040043

APA StyleSantos, P., Moreira, C., Gião, N., & Coelho, P. V. (2025). Chronic Osteomyelitis of the Jaws: Management and Outcomes in a Tertiary Maxillofacial Surgery Unit. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 18(4), 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/cmtr18040043