Facial Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:Introduction

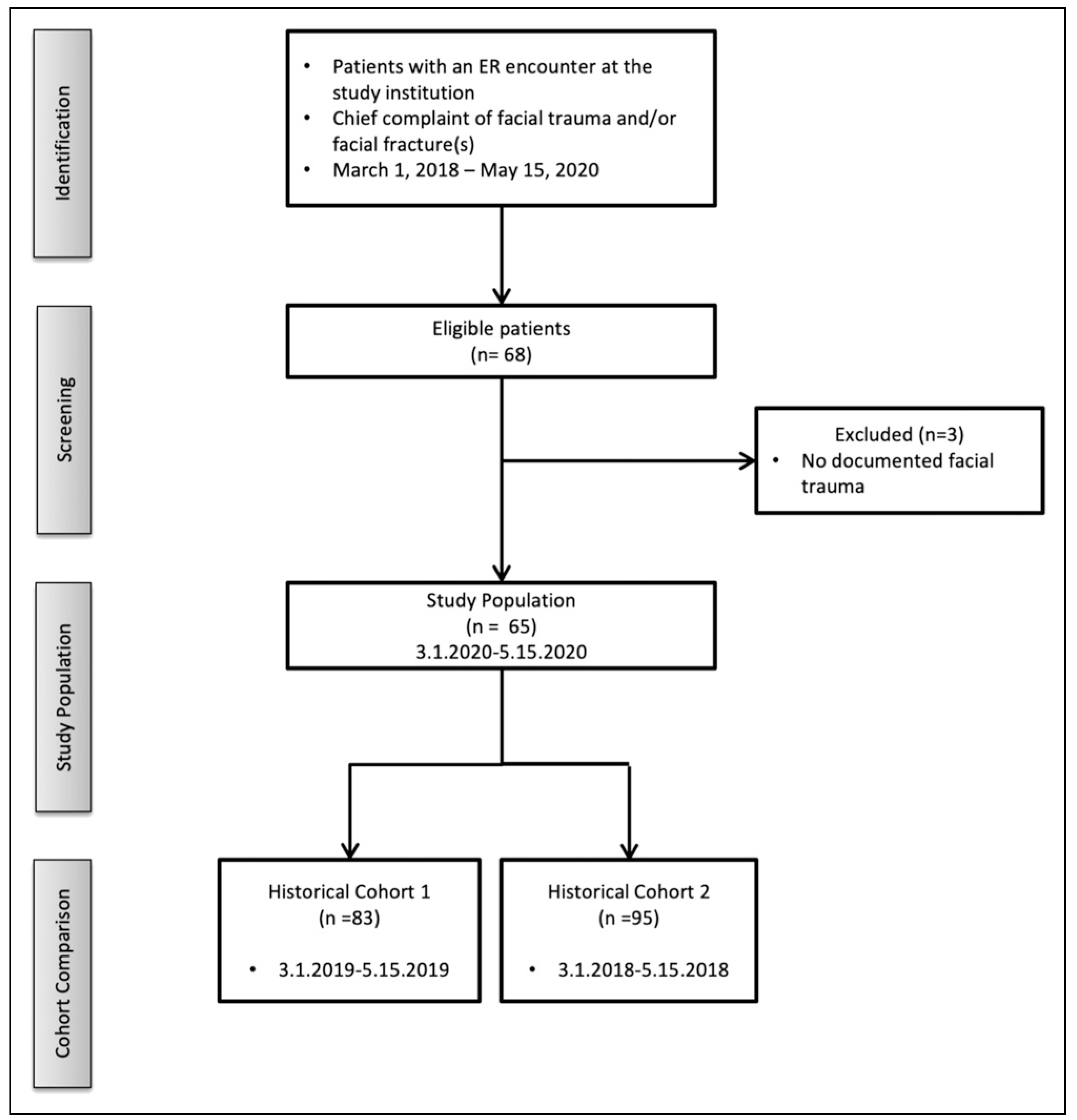

Methods

Patient Selection and Data Collection

Study Period and Endpoints

Statistical Analysis

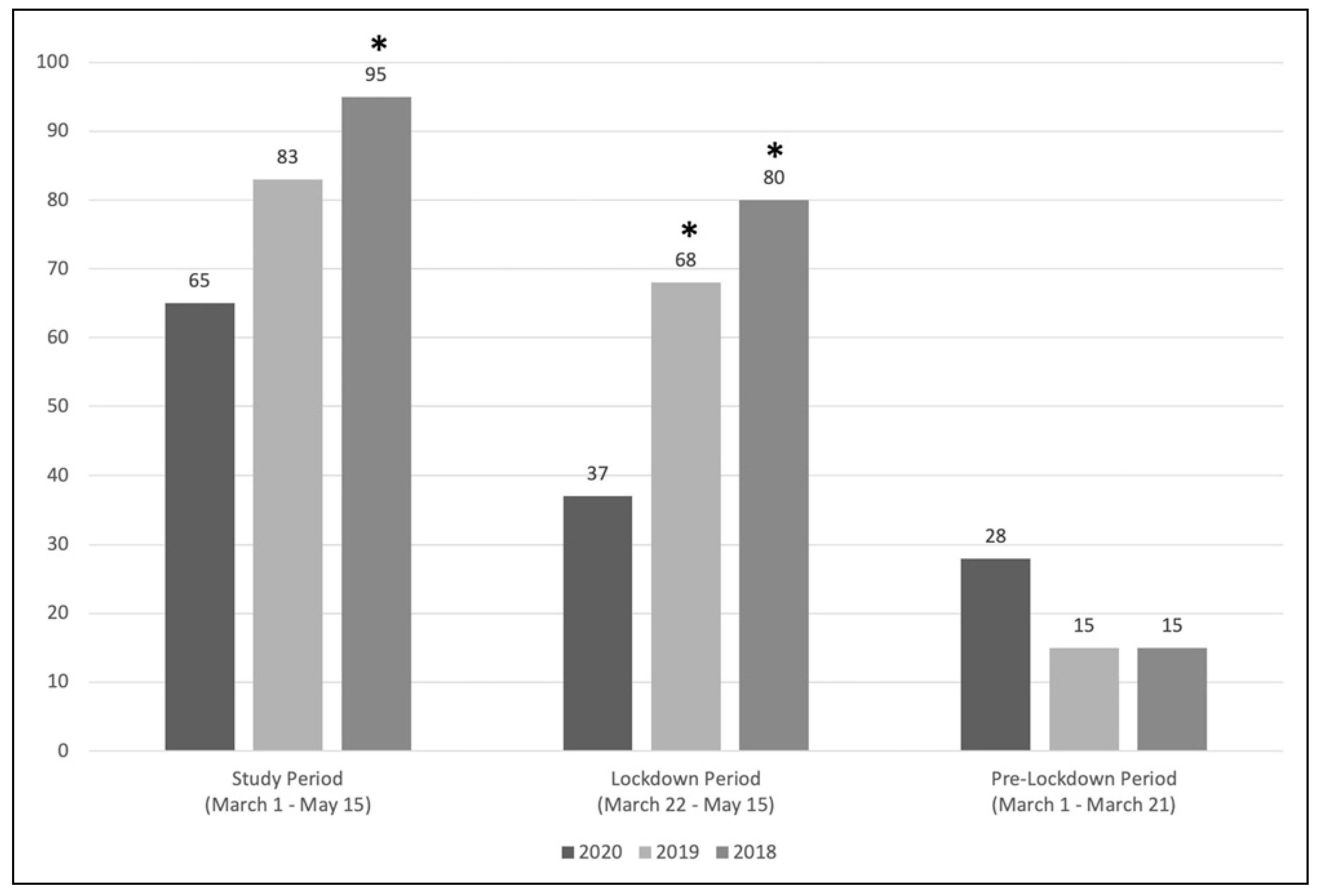

Results

Discussion

COVID-19 and Incidence of Facial Trauma

Variations in Facial Trauma Patterns

Study Limitations

Conclusion

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Ethical approval

References

- McLean, I. Climatic effects on incidence of sexual assault. J Forensic Leg Med. 2007, 14, 16–19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thomas, J.; Lynham, A.; Borgna, S.; Jones, L.; Vasani, S. Climatic effects on the incidence of interpersonal maxillofacial trauma. Int J Publ Health Sci. 2017, 2, 124. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, K.H.; Qiu, M.; Sun, J. Temporal distribution of alcohol related facial fractures. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2017, 124, 450–455. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Olson, R.A.; Fonseca, R.J.; Zeitler, D.L.; Osbon, D.B. Fractures of the mandible: a review of 580 cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 1982, 40, 23–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, Y.; Ho, W.; Huang, Y.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 is an appropriate name for the new coronavirus. Lancet. 2020, 395, 949–950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- De Filippo, O.; D’Ascenzo, F.; Angelini, F.; et al. Reduced rate of hospital admissions for ACS during Covid-19 outbreak in Northern Italy. N Engl J Med. 2020, 383, 88–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hatchimonji, J.S.; Swendiman, R.A.; Seamon, M.J.; Nance, M.L. Trauma does not quarantine: violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Surg. 2020, 272, e53–e54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mick, P.; Murphy, R. Aerosol-generating otolaryngology procedures and the need for enhanced PPE during the COVID-19 pandemic: a literature review. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020, 49, 29. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Thamboo, A.; Lea, J.; Sommer, D.D.; et al. Clinical evidence based review and recommendations of aerosol generating medical procedures in otolaryngology—head and neck surgery during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020, 49, 28. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zou, L.; Ruan, F.; Huang, M.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral load in upper respiratory specimens of infected patients. N Engl J Med. 2020, 382, 1177–1179. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Libonati, C. Arrests plummet accross central New York during coronavirus pandemic. 13 April 2020. Available online: https://www.syracuse.com/crime/2020/04/arrests-plummet-across-central-new-york-duringcoronavirus-pandemic.html (accessed on 13 April 2020).

- Boserup, B.; McKenney, M.; Elkbuli, A. Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020, 38, 2753–2755. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- CDC COVID Data Tracker. Center for disease control and prevention (CDC). United States COVID-19 cases and deaths by state web site. 15 May 2020. Available online: https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_totaldeaths (accessed on 16 May 2020).

- Rezaeian, M. The association between natural disasters and violence: A systematic review of the literature and a call for more epidemiological studies. J Res Med Sci. 2013, 18, 1103–1107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Interpersonal Violence and Disasters; 2008; Available online: https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/violence/violence_disasters.pdf (accessed on 14 May 2020).

- Zhu, W.; Huang, X.; Zhao, H.; Jiang, X. A COVID-19 patient who underwent endonasal endoscopic pituitary adenoma resection: A case report. Neurosurgery. 2020, 87, E140–E146. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishihama, K.; Sumioka, S.; Sakurada, K.; Kogo, M. Floating aerial blood mists in the operating room. J Hazard Mater 2010, 181, 1179–1181. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ishihama, K.; Koizumi, H.; Wada, T.; et al. Evidence of aerosolised floating blood mist during oral surgery. J Hosp Infect. 2009, 71, 359–364. [Google Scholar]

- Hallier, C.; Williams, D.W.; Potts, A.J.; Lewis, M.A. A pilot study of bioaerosol reduction using an air cleaning system during dental procedures. Br Dent J. 2010, 209, E14. [Google Scholar]

- Urban, M.; Patel, T.; Raad, R.; et al. Implementation of preoperative screening protocols in otolaryngology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2020, 163, 265–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Study Period No. (%) | Control Periods No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 (n = 65) | 2019 (n = 83) | 2018 (n = 95) | P-value | |

| Age | 40.2 | 42.4 | 36.9 | .178 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 45 (69.2) | 51 (61.4) | 70 (73.7) | .212 |

| Female | 20 (30.8) | 32 (38.6) | 25 (26.3) | |

| Mechanism | ||||

| Assault | 31 (47.7) | 33 (39.8) | 50 (52.6) | .214 |

| Fall | 22 (33.8) | 29 (34.9) | 28 (29.5) | |

| MVA | 6 (9.2) | 10 (12.0) | 9 (9.5) | |

| Sports | 1 (1.5) | 8 (9.6) | 7 (7.4) | |

| Other | 5 (7.7) | 3 (3.6) | 1 (1.1) | |

| Domestic assault | ||||

| Yes | 3 (4.6) | 7 (8.4) | 7 (7.4) | .65 |

| No | 62 (95.4) | 76 (91.6) | 88 (92.6) | |

| EtOH or drug use | ||||

| Yes | 16 (24.6) | 19 (22.9) | 27 (28.4) | .687 |

| No | 49 (75.4) | 64 (77.1) | 68 (71.6) | |

| OHNS consult | ||||

| Yes | 46 (70.8) | 61 (73.5) | 76 (80.0) | .369 |

| No | 19 (29.2) | 22 (26.5) | 19 (20.0) | |

| Procedural intervention | ||||

| Yes | 28 (43.1) | 27 (32.5) | 41 (43.2) | .277 |

| No | 37 (56.9) | 56 (67.5) | 54 (56.8) | |

| OSH transfer | ||||

| Yes | 26 (40.0) | 21 (25.3) | 35 (36.8) | .123 |

| No | 39 (60.0) | 62 (74.7) | 60 (63.2) | |

| Prior facial trauma | ||||

| Yes | 8 (12.3) | 7 (8.4) | 6 (6.3) | .414 |

| No | 57 (87.7) | 76 (91.6) | 89 (93.7) | |

| Study Group No. (%) | Historical Controls No. (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 (n = 37) | 2019 (n = 68) | 2018 (n = 80) | P-value | |

| Age | 40.6 | 43.6 | 36.9 | .136 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 26 (70.3) | 41 (60.3) | 60 (75.0) | .153 |

| Female | 11 (29.7) | 27 (39.7) | 20 (25.0) | |

| Mechanism | ||||

| Assault | 19 (51.4) | 28 (41.2) | 42 (52.5) | .0617 |

| Fall | 11 (29.7) | 27 (39.7) | 24 (30.0) | |

| MVA | 3 (8.1) | 5 (7.4) | 8 (10.0) | |

| Sports | 0 (.0) | 6 (8.8) | 6 (7.5) | |

| Other | 4 (10.8) | 2 (2.9) | 0 (.0) | |

| Domestic assault | ||||

| Yes | 3 (8.1) | 4 (5.9) | 6 (7.5) | .891 |

| No | 34 (91.9) | 64 (94.1) | 74 (92.5) | |

| Procedural intervention | ||||

| Yes | 15 (40.5) | 21 (30.9) | 35 (43.8) | .264 |

| No | 22 (59.5) | 47 (69.1) | 45 (56.3) | |

| EtOH or drug use | ||||

| Yes | 13 (35.1) | 16 (23.5) | 23 (28.8) | .444 |

| No | 24 (64.9) | 52 (76.5) | 57 (71.2) | |

| OHNS consult | ||||

| Yes | 28 (75.7) | 51 (75.0) | 64 (80.0) | .743 |

| No | 9 (24.3) | 17 (25.0) | 16 (20.0) | |

| OSH transfer | ||||

| Yes | 16 (43.2) | 18 (26.5) | 27 (33.7) | .213 |

| No | 21 (56.8) | 50 (73.5) | 53 (66.3) | |

| Prior facial trauma | ||||

| Yes | 1 (2.7) | 7 (10.3) | 5 (6.3) | .326 |

| No | 36 (97.3) | 61 (89.7) | 75 (93.7) | |

© 2021 by the author. The Author(s) 2021.

Share and Cite

Tipirneni, K.E.; Gemmiti, A.; Arnold, M.A.; Suryadevara, A. Facial Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofac. Trauma Reconstr. 2022, 15, 318-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211053760

Tipirneni KE, Gemmiti A, Arnold MA, Suryadevara A. Facial Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction. 2022; 15(4):318-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211053760

Chicago/Turabian StyleTipirneni, Kiranya E., Amanda Gemmiti, Mark A. Arnold, and Amar Suryadevara. 2022. "Facial Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic" Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction 15, no. 4: 318-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211053760

APA StyleTipirneni, K. E., Gemmiti, A., Arnold, M. A., & Suryadevara, A. (2022). Facial Trauma During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Craniomaxillofacial Trauma & Reconstruction, 15(4), 318-324. https://doi.org/10.1177/19433875211053760