Abstract

Introduction/Objecive: There are very few studies that have investigated equestrian-related maxillofacial injuries. A retrospective review was performed to investigate maxillofacial horse trauma at a Level 1 Trauma Centre at the Royal Stoke Hospital over the last 10 years between 2010 and 2020. Study Design/Methods: Search of the hospital’s major trauma database as well as ED records showed 51 patients who sustained maxillofacial injuries related to horses. Statistical analysis was performed using Chi Squared tests. Results: 41 patients were female and the remaining 10 were male. 43% of patients were female and aged 30 and under. Kicks from horses accounted for 64.4% of equine-related maxillofacial injuries. A total of 90 injuries were recorded. Hard tissue injuries which include all fractures accounted for 66.3% of injuries sustained. 70.5% patients sustained isolated maxillofacial trauma. There was an association between patients sustaining non-isolated maxillofacial trauma and hard tissue maxillofacial injuries (P = 0.04). 65.6% of injuries were managed operatively. Patients aged 30 and under were more likely to be managed operatively (P = 0.03). Conclusion: Equestrian related maxillofacial trauma represents a proportion of trauma workload. The safety aspect of horse riding should be considered and education in safe riding and the use of appropriate safety equipment is vital.

Introduction

Maxillofacial injuries are a common presentation in Accident and Emergency departments up and down the United Kingdom (UK). They range from soft tissue injuries to severe craniofacial injuries requiring the input of multiple specialist teams including Emergency physician’s, Oral & Maxillofacial surgeons, Neurosurgeons, Anaesthetists, and Intensivists.

An often-overlooked aspect of maxillofacial injuries are those injuries which are sustained as result of trauma caused by a horse. Horse riding remains popular as a leisure activity certainly in the UK with a thriving equestrian sporting industry. Approximately 4.3 million people in the UK ride horses, and the equestrian industry is worth a reported £7 billion as well as providing employment for over 200,000 people.[1] In a recent study 41% of injuries caused involved the spine.[2] There are few studies which shows their impact in the head and neck region, specifically facial injuries. Horse trauma is noted to be more dangerous than rugby injuries and motorcycle accidents.[2,3] This is in part due to the high position of the rider as well as the force of a direct kick from a horse, which can be up to 10 000 newtons. The unpredictability of an animal also contributes to severity of the injury with mechanism of injury varying from a direct kick, fall, bite and being trampled on.

Major trauma centers are located around the country and serve as tertiary trauma care hubs for adults, children, or both. Royal Stoke Hospital as part of the University Hospitals of North Midlands Trust is a trauma center for adults covering the geographical areas of North West Midlands and North Wales, serving a population of approximately 2.5million people. This study evaluates the incidence, aetiology, demographics, fracture patterns, management and follow-up of equestrian-related maxillofacial trauma. The information obtained can be used to understand the impact of injuries sustained by patients, outcomes of management and future considerations regarding the safety aspect of horse riding.

Study Design/Method

All patients who had sustained horse-related maxillofacial injuries and been seen in Royal Stoke Hospital in the past 10 years (2010-2020) were included in this study. Information on patients was obtained from the TARN (Trauma Audit & Research Network) database and a record of Emergency Department attendees using keyword search maintained by the hospital; this was then cross-referenced with historic handover data kept by the maxillofacial department. Patient records stored electronically were retrospectively analyzed and information was collated. Information obtained included: age group; gender; type of injury; mechanism of injury; categorization of injury; concurrent head-injury; other non-maxillofacial injuries; treatment/management; follow-up; complications; and further procedures if applicable. Data was stored in tables and statistical analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel spreadsheet software. The dataset was analyzed for a relationship between demographics and type of injury as well as mechanism of injury. Statistical significance was determined using Chi squared tests.

Results

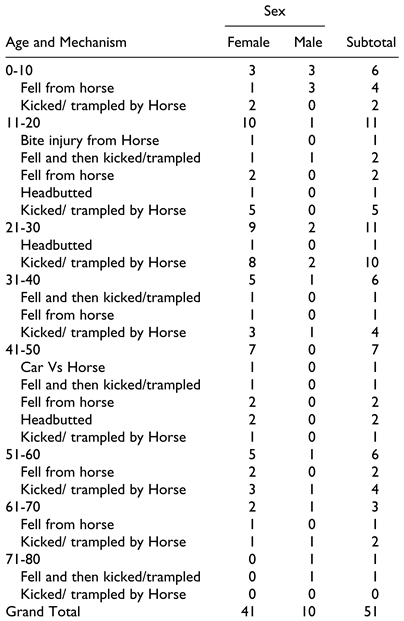

A total of 51 patients were identified. Results show comparison of injuries as well as treatment. Of the total number of patients identified (n = 51), 41 were female and 10 were male. The median age of these patients was 29 years, and the mean age was 32.7 years. The 11-20 and 21-30 age groups sustained the greatest number of injuries (n = 22). Females aged 30 and underrepresented nearly half of the patients identified (43%, n = 22). Table 1 indicates most common mechanism of injury involved a direct blow from a horse such as a kick or being trodden on. This is reflected in Table 1 and true for male and female as well as all age groups with the exception being the 41-50 age group. In total 31 patients were either kicked or trodden on and an additional 5 patients fell and were then kicked or trodden on.

Table 1.

Comparison of the Number of Injuries Caused by Horses by Age, Gender and Mechanism.

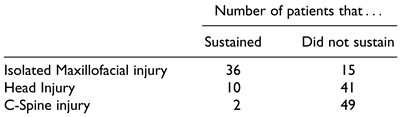

A total of 95 injuries were recorded. Hard tissue injuries accounted for 66.3% of injuries sustained (n = 57). Table 2 shows soft lacerations were the most commonly seen injuries (n = 32); the next most common were orbital fractures (n = 12). In both cases the mechanism most commonly associated was being kicked or being trampled on by a horse. Of the total injuries sustained 70.5% (n = 36) were isolated maxillofacial trauma. Patients who sustained nonisolated injuries were associated with a greater number of hard tissue injuries compared to patients who had isolated maxillofacial injuries (P = 0.04). 19.6% (n = 10) patients also sustained a head injury, with 1 patient dying as a result of intra-cranial trauma. Patients who sustained a head injury as well as maxillofacial injuries were associated with a greater number of hard tissue injuries (P = 0.02). Additionally, 2 patients sustained c-spine fractures shown in Table 3.

Table 2.

Number and Type of Injuries Sustained and the Causative Mechanism.

Table 3.

Number of Patients with Multiple Injuries.

A total of 31 injuries were managed conservatively, and 59 managed operatively. Four skull base injuries noted in Table 2 were not included in treatment total, Table 4, as was management of infection with antibiotics. Most mandibles (n = 7) were managed conservatively (n = 5) compared to soft tissue lacerations (n = 32) which were almost exclusively managed operatively (n = 31). There was no statistical significance between whether male and females were managed operatively or conservatively. Similarly, there was no statistical significance between whether patients aged 30 and under were managed operatively or conservatively. However, when excluding soft tissue lacerations and comparing the management of facial fractures, patients aged 30 and under were associated with being managed operatively as a opposed to conservatively in comparison to patients aged over 30 (P = 0.03). Four patients required revision surgery or further procedures after initial management.

Table 4.

Management of Maxillofacial Trauma Caused by Horses.

Discussion

The aetiology, demographics and treatment data are vital to our understanding of how to manage horse related maxillofacial injuries. Trauma caused by horses has been well documented however very few have focused on maxillofacial injuries and to our knowledge this is the first study performed at a UK trauma center.

Horse related trauma can result in severe craniofacial injuries with life threatening consequences. This has been reflected elsewhere.[4,5,6,7] This is likely due to the large forces of a horse kick or the impact of being thrown at significant force resulting in collision. One such example of a 15-year-old patient sustaining a mandible fracture gained nationwide press; it was described by the operating surgeon as “one of the most significant injuries that I have seen in a child outside of areas of conflict.”[8]

Our results clearly showed that younger females, aged 30 or under, were the most common demographic accounting for 43% of patients. This pattern is reflected in other studies.[9,10,11] This may be explained as equestrian sports and activities have a higher number of young female participants.[12] Patients aged older than 30 that sustained injuries were also primarily female which is not reflected elsewhere as the ratio of male and female patients over 30 were found to be similar.[11] Future analysis could include if patients were mounted or unmounted and the experience level of the rider as to whether this affects the likelihood of sustaining maxillofacial trauma.

The mechanism of injury demonstrated in our study closely mirrored other studies showing that kicks by horses were responsible for the most maxillofacial injuries, and for a wide range of traumatic injuries.[9,10,11,13] This is in contrast to Meredith and Antoun,[14] Abdulkarim et al[15] and Kriss and Kriss[16] which found that falls were the most frequent mechanism of injury. The same studies also found that falls were associated with lower and upper limb injuries. Our study did not collect data on whether patients were wearing helmets or not as this data was found to be inconsistently recorded. Although wearing helmets or other head protective equipment has been shown to reduce the incidence of head injuries, it remains to be seen whether helmets can reduce maxillofacial trauma as they do not directly protect the face unless installed with a face guard.[9] It is of the authors view that helmets should be mandatory as conclusions drawn from other studies show that they contribute to prevention of serious intra-cranial injuries.[17] O’Brien[18] reported that certain types of equestrian activities such as hunting, and the cross-country element of hunting are associated with an increased risk of injury due to the horses traveling at high speed.

Site of injury varied however results showed that the middle third of the face was most commonly affected when soft tissue lacerations were excluded. This pattern is consistent with other comparable studies.[10,11] Due to the overall force of the animal, injuries caused by horses can be associated with trauma caused by other large animals and motor vehicles which have similar fracture patterns and severity of injuries.[19] Our results clearly demonstrated a greater association of hard tissue injuries with nonisolated maxillofacial fractures and accompanying head injuries were noted.

Operative management accounted for the majority of injuries as previously observed.[11] This may be due to severity of injury causing functional and or aesthetic deficit which demands operative intervention. It remains to be seen whether injuries caused by horses amounted to an increased incidence of operative intervention when compared to the total number of traumatic maxillofacial injuries treated in the unit. Our results show that when excluding soft tissue injuries, patients under the age of 30 were more likely to be managed operatively.

We recognize the limitations of our study including limited sample size and having no standardized method of obtaining data on patients who fit the criteria. We hope that some of the limitations of this study give scope for further investigations such as comparison of our data set with equestrian related non-maxillofacial injuries.

In conclusion, maxillofacial trauma caused by horses represents an important proportion of workload by a maxillofacial department and requires coordination between multiple hospital specialities to achieve satisfactory outcomes for patients. The education and implementation of safety recommendations should also be a priority in anyone participating in equestrian activities.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr Diane Adamson—Emergency Medicine & Trauma Consultant at University Hospitals of North Midlands and Mr Douglas Mobley—Operational Data Service Manager at University Hospitals of North Midlands for their assistance with data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Sandiford, N.; Buckle, C.; Alao, U.; Davidson, J.; Ritchie, J. Injuries associated with recreational horse riding and changes over the last 20 years: a review. JRSM Short Rep. 2013, 4, 2042533313476688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, F.; Govilkar, S.; Woo, T.; Britton, I.; Youseff, B.; Lim, J. Injury patterns of equine-related trauma. The Open Orthopae- dics Journal. 2019, 13, 130–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ball, C.; Ball, J.; Kirkpatrick, A.; Mulloy, R. Equestrian injuries: incidence, injury patterns, and risk factors for 10 years of major traumatic injuries. Am J Surg. 2007, 193, 636–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, L.; Ekman, R.; Thomson, R. Horse-related incidents and factors for predicting injuries to the head. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med. 2018, 4, e000398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pounder, D. “The grave yawns for the horseman”: equestrian deaths in South Australia 1973-1983. Med J Aust. 1984, 141, 632–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papachristos, A.; Edwards, E.; Dowrick, A.; Gosling, C. A description of the severity of equestrian-related injuries (ERIs) using clinical parameters and patient-reported outcomes. Injury. 2014, 45, 1484–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zuckerman, S.; Morgan, C.; Burks, S.; et al. Functional and structural traumatic brain injury in equestrian sports: a review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2015, 83, 1098–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- BBC. Teenager’s jaw rebuilt after horror horse accident in Derbyshire [Internet]. BBC News. Published October 8, 2019. Available online: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-south-yorkshire-49971866 (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Islam, S.; Gupta, B.; Taylor, C.; Chow, J.; Hoffman, G. Equine-associated maxillofacial injuries: retrospective 5-year analysis. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2014, 52, 124–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Antoun, J.; Steenberg, L.; Lee, K. Maxillofacial fractures sustained by unmounted equestrians. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2011, 49, 213–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singleton, C.; Manchella, S.; Nastri, A. Operative management of equine-related maxillofacial trauma presenting to a Melbourne level-one trauma centre over a six-year period. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2019, 57, 1126–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- British Equestrian Trade Association. Market Information [Internet]. Beta-uk.org. Published 2019. Available online: https://www.beta-uk.org/pages/industry-informa tion/market-information.php (accessed on 3 February 2021).

- Lee, K.; Steenberg, L. Equine-related facial fractures. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2008, 37, 999–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meredith, L.; Antoun, J. Horse-related facial injuries: the perceptions and experiences of riding schools. Inj Prev. 2010, 17, 55–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdulkarim, A.; Juhdi, A.; Coffey, P.; Edelson, L. Equestrian injury presentations to a regional trauma centre in Ireland. Emerg Med Int. 2018, 7394390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriss, T.; Kriss, V. Equine-related neurosurgical trauma: a prospective series of 30 patients. J Trauma. 1997, 43, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bier, G.; Bongers, M.; Othman, A.; et al. Impact of helmet use in equestrian-related traumatic brain injury: a matched-pairs analysis. Br J Neurosurg. 2017, 32, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Brien, D. Look before you leap: What are the obstacles to risk calculation in the equestrian sport of eventing? Animals (Basel). 2016, 6, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norwood, S.; McAuley, C.; Vallina, V.; Fernandez, L.; McLarty, J.; Goodfried, G. Mechanisms and patterns of injuries related to large animals. J Trauma. 2000, 48, 740–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2021 by the authors. The Authors 2021.