1. Introduction

Opioid-related morbidity and mortality has become a public health crisis in the last 30 years. In 2016, approximately 2.1 million people were affected by an opioid-use disorder, and more than 17,000 opioid-related deaths occurred in the United States [

1,

2]. This is a particularly troubling issue in surgical fields given surgeons prescribe 10% of all opioids [

3], and opioid use in the perioperative period has been identified as a significant risk factor for long-term opioid dependence [

4,

5,

6,

7]. Furthermore, nearly 40% of opioid-related deaths are due to consumption of prescription opioids [

8]. Despite this, opioids are continually used for perioperative pain control following facial fractures.

In the 1990s, it was noted surgeons were underassessing and undertreating pain [

9]. In response, the pain standard was updated by the Joint Commission to include the 10-point pain scale as the fifth vital sign [

10]. Unfortunately, these changes had unintended consequences. Physicians began prescribing increased amounts of opioid medications, which led to a surge in prescription opioidrelated deaths [

11]. In 2017, the Department of Health and Human Services declared a public health emergency known as the opioid crisis.

Multiple efforts have been aimed at combatting the opioid epidemic at clinical and legislative levels. As of 2019, 33 states have enacted a policy to address prescribing practices [

12]. Those policies concerning acute and postoperative pain are most applicable to surgeons. In North Carolina, this type of policy took the form of the Strengthen Opioid Misuse Prevention Act (NC STOP Act), which came into effect on 1 January 2018 [

13].

The NC STOP Act addressed prescribing practices for acute pain, which is defined as pain expected to last no more than 3 months. The legislation had 3 key aspects of interest to surgeons. The first stipulation was that an opioid prescription written for an acute injury could not exceed a 5-day supply. Secondly, no more than a 7-day supply could be prescribed postoperatively. Lastly, prescribers were required to perform a review of the NC Controlled Substances Reporting System (PMP AWARE) for a patient’s 12-month controlled substance history prior to providing an initial prescription for a Schedule II or III medication [

13].

The efficacy of the NC STOP Act has not been evaluated in craniofacial surgery. This retrospective populationbased cohort study aims to assess for a change in the overall quantity of opioids prescribed in facial fracture repair before and after the NC STOP Act. A secondary aim was to assess for a treatment bias and a change in prescription patterns across different surgical specialties, including plastic surgery and otolaryngology in the treatment of similar injuries.

2. Methods

Institutional review board approval for this study was obtained. A retrospective cohort of patients who sustained facial fractures and underwent operative repair from 1 January 2015 to 31 December 2019 at a single level 1 trauma center were identified. Patients were excluded if they were less than 13 years of age or if they sustained multisystem trauma.

Given the North Carolina STOP Act was enacted on 1 January 2018, patients who underwent facial fracture repair prior to that date were included in the “Before” group, and those following that date were included in the “After” group.

Patient demographics, including age at surgery, gender, race, insurance, the presence of comorbidities, tobacco use, and substance use were collected. Clinical characteristics, including mechanism of injury, date of injury, date of surgery, and the specialty of the surgeon were noted. Each case was categorized based on the anatomic region of the surgically treated fracture into one of the following subgroups: mandible; isolated orbital; midface, including zygomatic-maxillary-complex fractures and Le Fort type fractures; and multiple regions, which included cases of surgically treated fractures of more than one of the above categories. Further subgroup analysis was conducted based on the surgical specialty of the operative surgeon: otolaryngology or plastic surgery.

Perioperative opioid prescription data were obtained from PMP AWARE, a multi-state database which includes prescribing information about every controlled substance dispensed. The perioperative period was defined as the time period between the date of injury and 30 days following the surgery. Due to variations in medications and dosages prescribed, the total dose and strength of each opioid was converted into morphine milligram equivalents (MME) (Equation 1) to allow for comparisons among prescriptions (

Table 1).

To evaluate for the over-prescription of opioids, each patient’s chart was reviewed for an opioid prescription, followed by evaluation of prescription fill status as noted in PMP AWARE. The fill rate was defined as the number of patients who filled an opioid prescription, divided by the total number of the prescriptions written (Equation 2). The fill rate was determined for the before and after groups.

Data for the before and after groups were summarized using descriptive statistics: means were compared for continuous variables (age, MME) using student’s t-test for analysis. Chi-square tests were used for categorical variables (gender, race, insurance status, comorbidities, substance use, tobacco use, mechanism of injury, specialty of the surgeon, and fill rate). Statistical significance for all parameters was set at a value of p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Demographics

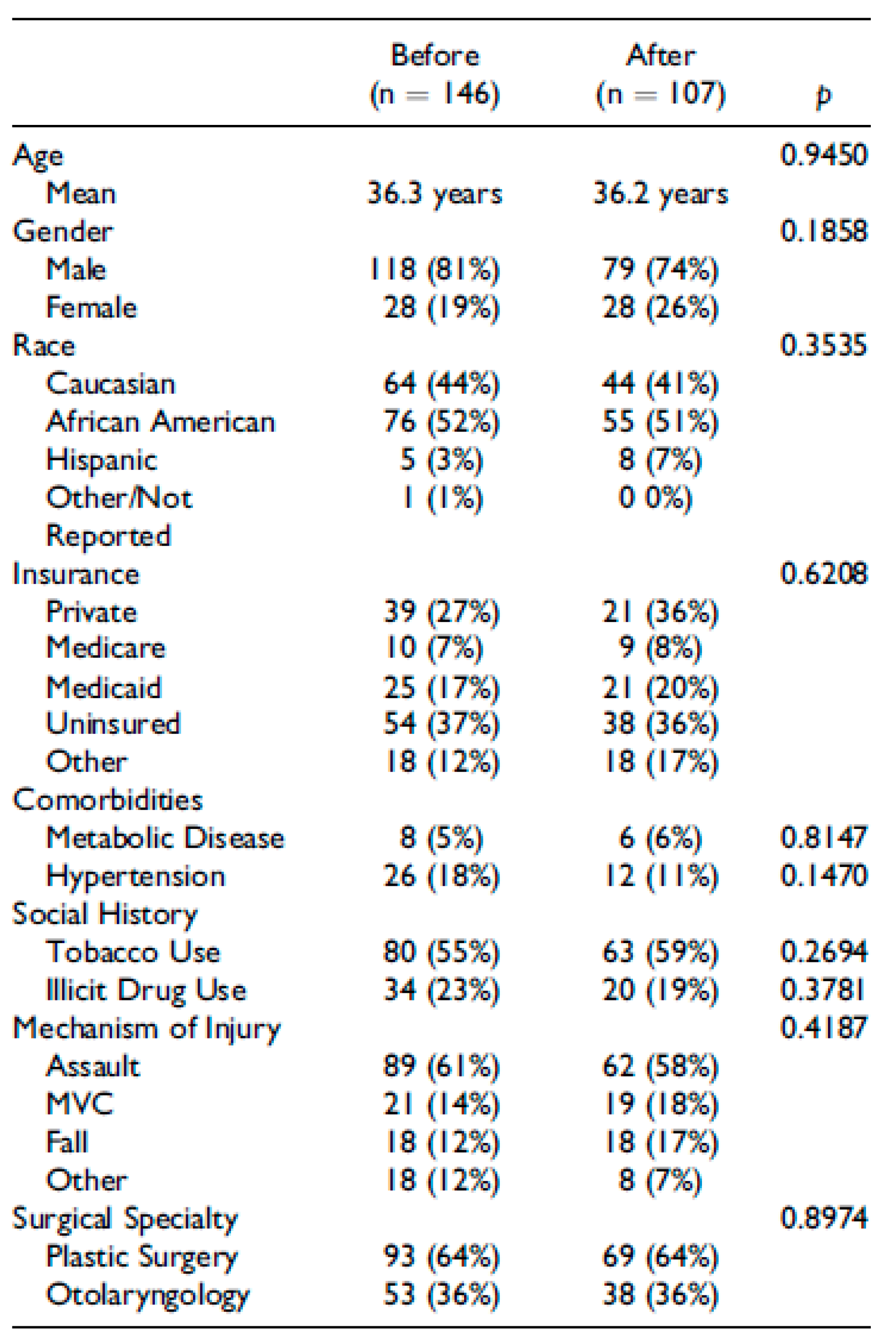

Of the 253 patients who met inclusion criteria, 146 were treated before enactment of the NC Stop Act and 107 were treated after. The demographics, medical comorbidities, and clinical characteristics did not differ between the 2 groups (

Table 2).

3.2. Prescription Trends

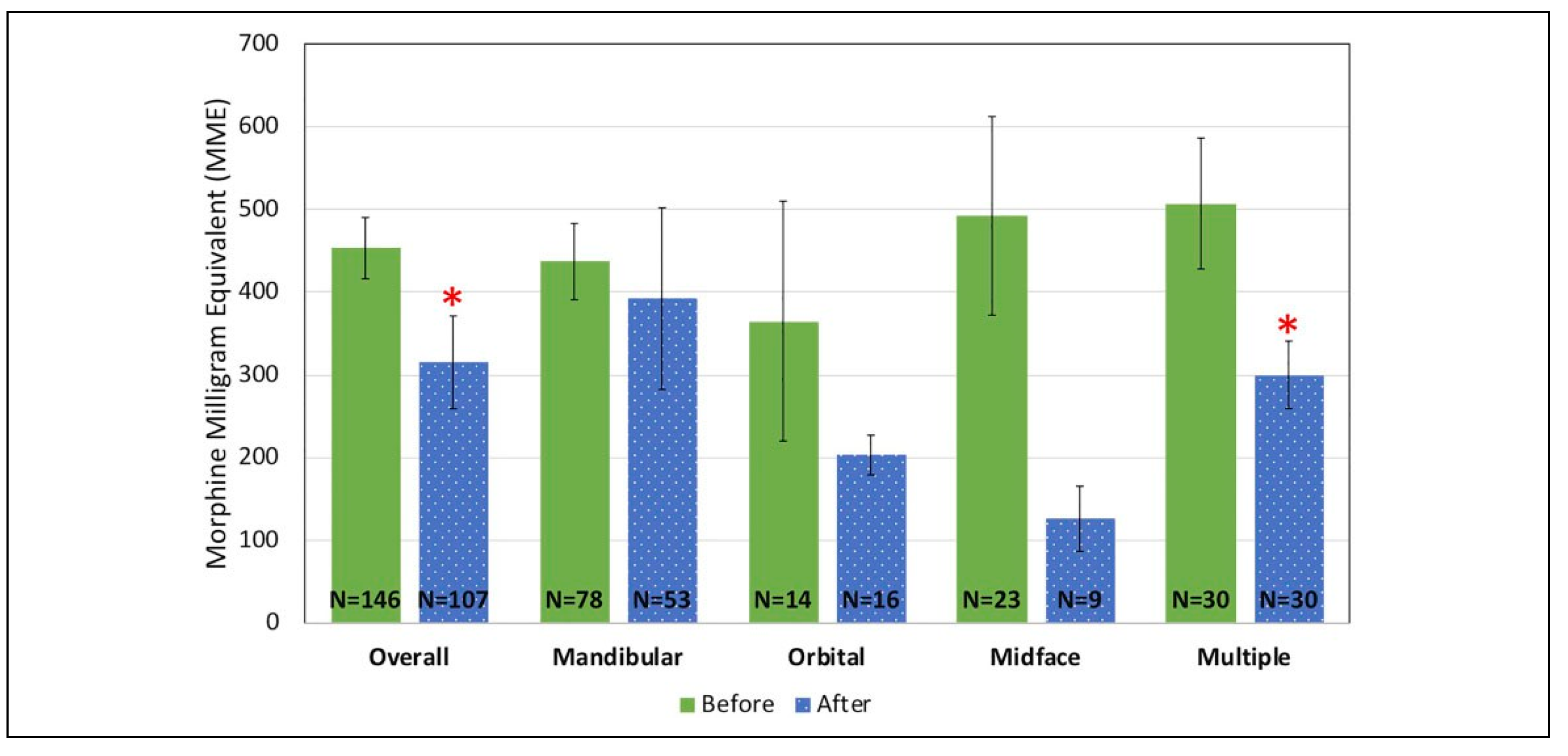

Prior to the enactment of the North Carolina STOP Act in 2018, the average perioperative opioid dose in each patient who underwent facial fracture repair was 453 MME (

Figure 1). After implementation, there was a 30.9% reduction to 315 MME dispensed (

p = 0.038), reaching statistical significance. Subgroup analysis of fractures of multiple regions (n = 60) demonstrated a 40.8% reduction, from 507 to 300 MME (

p = 0.024). There were clinically significant reductions in the subgroups of mandible, isolated orbital, and midface, but they did not reach statistical significance. The mandible subgroup (n = 132) showed an 11.3% reduction, from 437 to 392 MME (

p = 0.675). Opioid prescriptions filled in the isolated orbital subgroup (n = 30) were reduced by 44%, from 365 to 203 MME (

p = 0.246). Opioid prescribing in the midface (n = 32) subgroup was reduced by 74.6% from 492 to 126 MME (

p = 0.069).

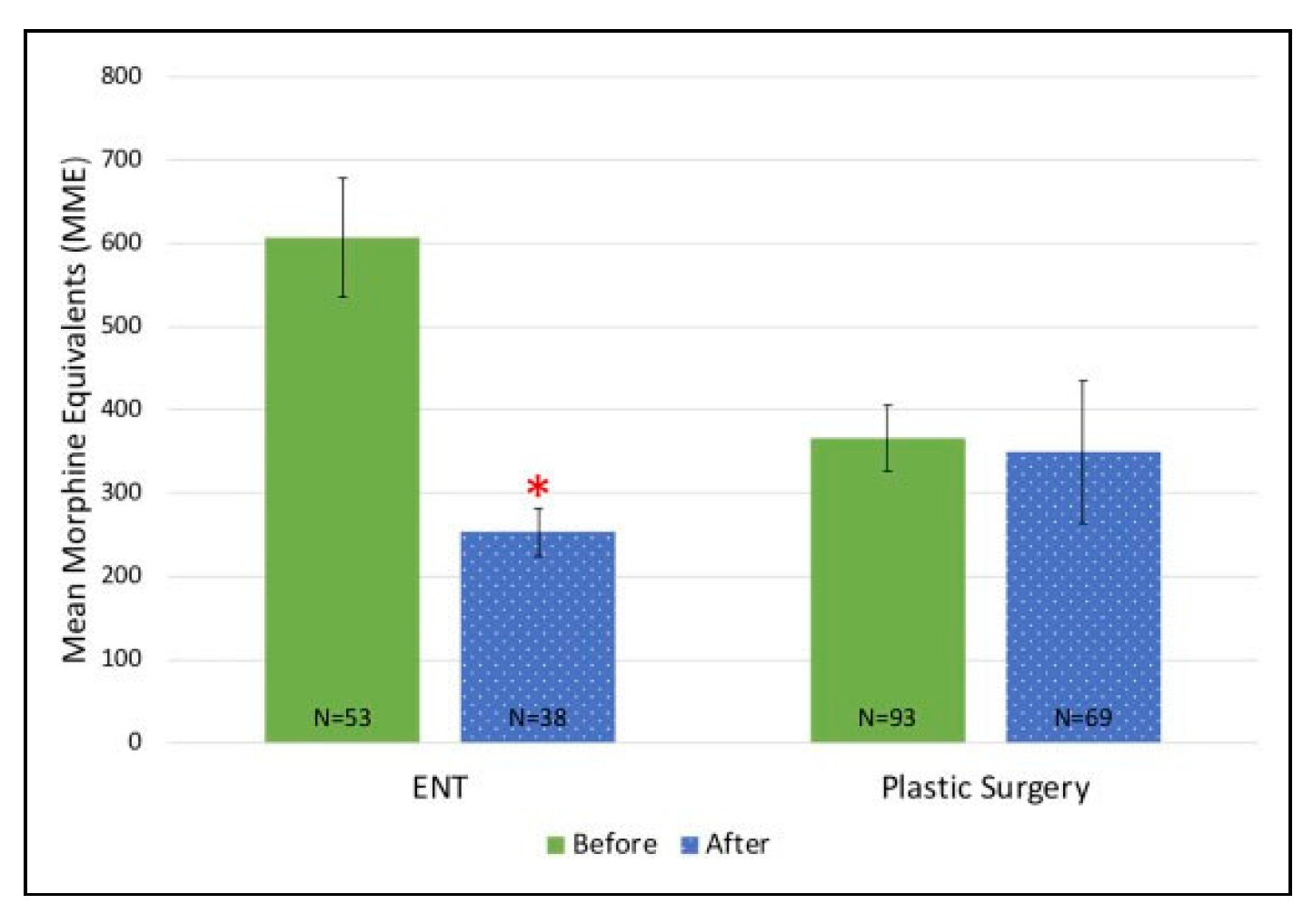

Subgroup analyses of plastic surgeons’ prescribing practices revealed a 5.4% reduction of prescribed opioids dispensed, from 366 to 350 MME (

p = 0.828). Otolaryngologists demonstrated a statistically significant, 58.3% reduction in opioid prescribing from 607 to 253 MME (

p < 0.0001) (

Figure 2).

In both the before and after groups, 95% of patients received a prescription for opioids. The 2 groups had an 88% and a 91% fill rate, respectively (p = 0.4873).

4. Discussion

Appropriate use of opioids in surgical patients presents a challenge for physicians and surgeons. Two competing interests must be balanced: the management of acute pain and minimization of chemical dependency as a result of opioid use following surgery. Prior to recognition of the addictive nature of opioid medications, prescribing practices were not regulated. However, in the face of the observed increase of opioid-related overdoses and deaths, it became evident legislative intervention would be necessary to combat the growing crisis.

Our data indicate that following the North Carolina Strengthen Opioid Misuse Prevention Act, there was a 30.9% reduction of narcotic prescriptions in facial fracture treatment at our institution, which was both clinically and statistically significant. The decrease was also observed in the multi-region fracture subgroup. A clinically significant reduction was seen in the isolated orbital and midface subgroups, although these subgroups were underpowered and did not reach statistical significance.

These findings are supported in a study by Aran et al., which noted a 35% reduction of average MME prescribed to orthopedic trauma patients following the NC STOP Act [

14]. In contrast to their work, our study utilized the NC Controlled Substance Database (PMP AWARE), rather than the electronic medical record. Every controlled substance prescription written in North Carolina is entered into this database, therefore it provides a more accurate representation of opioid prescriptions filled by each patient than does reviewing the patient’s chart.

Analysis of the opioid fill rate was performed to measure excess prescriptions. An unfilled prescription is assumed to be not required by the patient. Following NC STOP Act, fewer opioids were prescribed and the fill rate did not change significantly, suggesting patients’ pain requirements are still being met. The reduction of average MME and no significant change in fill rate suggests that prior to NC STOP Act, a pattern of over-prescription existed. It is possible surgeons were previously overestimating opioid requirements in facial fracture repair. The excess opioids in the community at that time had the potential for misuse and diversion. This is consistent with a study by Lapidus et al. who found inappropriate prescribing occurred at high rates (39%) in facial trauma which underwent surgical repair. Inappropriate prescribing was defined as greater than 100 MME daily, overlapping opioid prescriptions, and co-prescription with benzodiazepines [

15].

In comparing subgroups, a relatively smaller reductionof perioperative MME (11.3%) was noted in mandibular fractures. It is possible postoperative maxillomandibular fixation leads to increased patient discomfort, requiring higher opiate requests. This is supported in a study by Peisker et al. which showed patients with mandibular fractures report significantly higher mean maximal pain in a questionnaire than those with malar, maxillary, zygomatic, or orbital fractures [

16].

Annually, facial fractures account for over 400,000 emergency department visits in the United States [

17]. These fractures are commonly treated by plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists.

Our data indicate that prior to the act, a prescribing bias existed between the departments of otolaryngology and plastic surgery at our institution. Otolaryngologists were prescribing more opioid medications than plastic surgeons prior to enactment of the NC STOP Act. After the legislation in 2018, similar prescribing practices are present. Given there is multispecialty involvement in facial fracture treatment, standardization of pain control is necessary to protect patients from opioid dependence and misuse.

This study is not without limitations. It is restricted to a review of 2 surgical specialties at a single academic center. Additionally, PMP AWARE identifies filled prescriptions, but does not quantify the amount of opioids consumed by each patient. Future multicenter studies across multiple specialties evaluating opioids consumed are needed to corroborate these findings. Further studies should analyze the economic impact of the legislation, considering the cost of the medication as well as the frequency of pain-related visits to a clinic or emergency department.

5. Conclusions

Our findings indicate that following the NC STOP Act, there were clinically and statistically significant reductions in opioid prescription in patients with surgically treated facial fractures overall. Clinically significant reductions in filled opioid prescriptions were also seen in all facial fracture subgroups and across specialties. In fact, more consistent prescribing practices were observed between plastic surgeons and otolaryngologists. Most notably there was a reduction in over-prescription of opioid medications. While combatting this crisis will continue to require a multi-pronged approach, this study suggests state level legislation can have an impact in reducing the amount of circulating opioids in the population. This is the first known assessment efficacy of a state’s legislation in reducing perioperative opioid prescription in facial fracture repair.