Abstract

Blunt trauma to the parotid resulting in the formation of a sialocele is rare, with only three cases identified in the literature. We present a unique case involving a 32-year-old man with blunt trauma resulting in a left mandibular angle fracture. The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the left mandibular angle fracture via transoral approach. At follow-up, after resolution of the edema from the injury, a sialocele was noted in the region of the left anterior parotid gland. The patient was treated conservatively with antisialagogues, pressure dressings, and multiple percutaneous aspirations that ultimately resulted in resolution of the sialocele.

Blunt trauma to the parotid region resulting in the formation of a sialocele is a rare occurrence. Posttraumatic sialocele formation is typically the result of penetrating trauma or surgical approaches that violate the capsule of the parotid or Stensen duct [1]. Blunt force trauma to the parotid significant enough to cause gland parenchyma or duct disruption is likely to be associated with fractures or disruption of other important head and neck structures.

A 32-year-old man presented with acute left facial swelling 10 hours after being struck in the left face and right ankle with a hammer during an altercation that resulted in a left mandibular angle fracture and right ankle fracture. The patient’s past medical history was unremarkable.

On initial physical examination, there was marked diffuse left facial edema. A 2-cm abrasion with associated ecchymosis was evident 2 cm below the left zygomatic arch and anterior to the lobule of the ear. The patient’s maximum incisal opening was 31 mm with deviation to the left upon opening. Intraoral edema was isolated to the left buccal mucosa. There was grade l mobility associated with the lower left third molar, and no hemorrhage was noted. The facial nerve examination was normal.

Computed tomography (CT) of the face was positive for a minimally displaced fracture of the left mandibular angle that was continuous with the periodontal ligament space of an erupted nonfunctional lower left third molar (Figure 1a–d). Inaddition to left mandibular angle fracture, the radiologist noted left-sided soft-tissue fullness that was thought to represent a possible hematoma that was 3.4 × 5.5 cm (Figure 2).

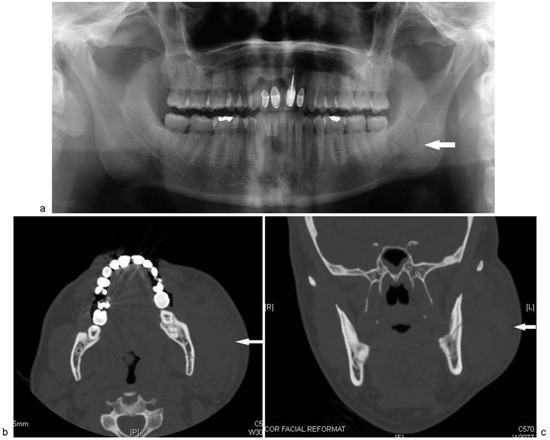

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative orthopanorex showing fracture of left mandibular angle with communication to the periodontal ligament space tooth no. 17. (b) Axial view on CT scan showing left mandibular angle fracture. (c) Coronal view on CT scan showing left mandibular angle fracture.

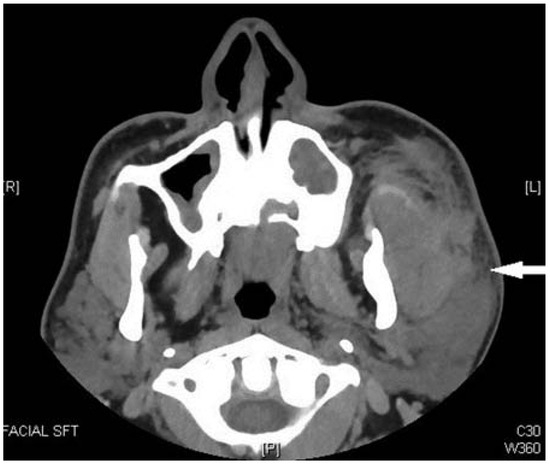

Figure 2.

Preoperative CT scan showing left-sided perimandibular fluid collection. This was initially read as a possible hematoma by the radiologist. Further inspection shows an intracapsular parotid fluid collection consistent with a sialocele.

The patient was taken to the operating room and under-went open reduction and internal fixation of the left mandibular angle fracture utilizing a miniplate osteosynthesis via transoral approach (Figure 3). The patient’s immediate postoperative course was uneventful and he was discharged thenext day.

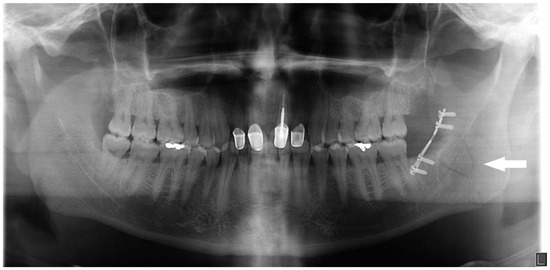

Figure 3.

Postoperative orthopanorex showing fixation of the left angle fracture with a 2.0 Champy plate.

The patient failed to return for 1 week follow-up and was seen 5 weeks postrepair. At this follow-up visit, the patient reported that he began to notice a fluctuant swelling several days following the injury as the surgical edema progressively resolved. He reported that the mass had not increased or decreased in size since he first noticed it. A 4 × 5 cm sized fluctuant swelling was noted over the left ascending ramus of the mandible. The mass was nontender to palpation. The patient was prepped and draped in a sterile fashion. The mass was aspirated percutaneously with an 18-gauge needle producing 20 mL of clear/yellow fluid (Figure 4a–d). A pressure dressing head-wrap was applied. Laboratory analysis of the fluid revealed an amylase value greater than 100,000 U/L. Aerobic and anaerobic cultures were negative.

Figure 4.

(a–d) Fluctuant left facial mass 5 weeks post-op. Aspiration of 20 mL of fluid from the mass. (d) Post-aspiration.

The patient returned 1 week later with a similar presentation. The mass was aspirated in the same fashion producing 15 mL of fluid. A bolster pressure dressing was applied to provide pressure over the sialocele. One week later. the patient returned with persistence of the left facial mass, although of a smaller size than previously. The mass was aspirated in the same fashion producing 10 mL of fluid. A pressure dressing head-wrap was applied. The patient was prescribed scopolamine 1.5-mg transcutaneous patches. At the subsequent visit, the mass was noted to have decreased in size. One week later, he returned with resolution of the sialocele. Healing of the fracture, as defined by clinical and radiographic evidence, was not compromised by the formation of the sialocele.

Discussion

The formation of a sialocele or salivary fistula secondary to penetrating trauma causing a disruption of the parotid capsule or Stensen duct is well established [1]. There are few reported cases of the formation of a sialocele or salivary fistula secondary to blunt trauma to the parotid gland, a search of the literature reveals only three cases [2]. Previous case reports do not provide the mechanism of injury. In this case the mechanism of injury is likely the focused blow by the hammer leading to parenchymal disruption.

Parotid injuries occur by either blunt or sharp trauma to the face. Vital structures to consider, when assessing the lacerations, include the parotid duct (Stensen duct) and branches of the facial nerve. Facial nerve injuries, if present, may require surgical intervention. Parotid duct injuries historically have been managed by exploration and/or primary repair (repair over a stent, ligation, or fistulization to the oral cavity) [3]. Successful conservative management has been described [3].

Parotid duct injuries have a low incidence of infection [3]. When a suspected ductal injury occurs, it is important to consider both medical and surgical therapies. Adequate wound care and adjunct antibiotics should be considered with any ductal injury. The drug of choice is amoxicillin/ clavulanate potassium (Augmentin 875/125 bid) [3]: Doxycycline 100 mg PO bid for penicillin-allergic patients and Rocephin 1 g intramuscularly or intravenously for suspected noncompliant patients [3]. Additionally, immunizations should be up-to-date and cover for Clostridium tetani [3].

Prior to the 1970s, the term used to define a saliva collection secondary to disruption of the parotid capsule or parotid duct was “pseudocyst,” as popularized by Landry in the 1950s [4]. It was not until the 1970s that the term “sialocele” was commonly used and in 1995 Van der Goten et al. differentiated a sialocele from a pseudocyst. He defined a “sialocele” as a collection of fluid in an epithelium lined cavity. A “pseudocyst” is a collection of fluid confined by connective tissue or fibrosis [5]. Confirmation of a sialocele or pseudocyst is performed through aspiration of the fluid, which shows an amylase level greater than 100,000 U/L [6]. The clinical presentation and management of a pseudocyst or sialocele is identical, and differentiation can only be made with histological examination. Despite Van der Goten et al.’s attempts at defining the nomenclature, the term “sialocele” is still commonly used in the literature to describe both pseudocyst and sialocele.

Multiple modalities have been described in the literature for the management of a parotid sialocele. These include, but are not limited to, pressure dressings, serial aspirations, antisialagogues, radiation therapy, botulinum toxin, primary repair of the duct if ductal injury is present, marsupialization of the sialocele, superficial or total parotidectomy, and/or parasympathetic nerve denervation (sectioning of the auriculotemporal or Jacobson nerve) [1,7,8,9,10,11]. Multiple modalities may be necessary to ensure complete resolution of a sialocele as in this case.

In the case presented, disruption of the glandular substance was evident on the initial CT, but was initially interpreted as representing a possible hematoma. This case illustrates the need for careful assessment of soft tissues on initial CT scans taken for maxillofacial trauma. A high index of suspicion for soft tissue injury should be maintained while reviewing scans to ensure diagnoses are not missed.

In summary, a case of parotid sialocele secondary to blunt trauma is presented. With proper recognition, such conditions can be successfully managed conservatively.

References

- Canosa, A.; Cohen, M.A. Post-traumatic parotid sialocele: Report of two cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 1999, 57, 742–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monfared, A.; Ortiz, J.; Roller, C. Distal parotid duct pseudocyst as a result of blunt facial trauma. Ear Nose Throat J 2009, 88, E15–E17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Barrera, J.; Kellman, R. Parotid Duct Injuries Treatment & Management. Available online: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/ 8686512013.

- Landry, R.M. Traumatic pseudocyst formation of the parotid duct: A safer method of obliteration. AMA Arch Surg 1958, 76, 97–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van der Goten, A.; Hermans, R.; Smet, M.H.; Baert, A.L. Submandibular gland mucocele of the extravasation type. Report of two cases. Pediatr Radiol 1995, 25, 366–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, D.; Glezerson, G.; Stewart, M.; Esser, J.; Lawson, H.H. Posttraumatic parotid fistulae and sialoceles. A prospective study of conservative management in 51 cases. Ann Surg 1989, 209, 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavanaugh, K.; Park, A. Postparotidectomy fistula: A different treatment for an old problem. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol 1999, 47, 265–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchese, R.R.; Blotta, P.; Pastore, A.; Tugnoli, V.; Eleopra, R.; De Grandis, D. Management of parotid sialocele with botulinum toxin. Laryngoscope 1999, 109, 1344–1346. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas, H.; Galati, L.T.; Parnes, S.M. A pilot study evaluating the treatment of postparotidectomy sialoceles with botulinum toxin type A. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000, 126, 421–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Epker, B.N.; Burnette, J.C. Trauma to the parotid gland and duct: Primary treatment and management of complications. J Oral Surg 1970, 28, 657–670. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Haller, J.R. Trauma to the salivary glands. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1999, 32, 907–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the author. The Author(s) 2016.