Abstract

Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) has emerged as an important and increasingly common comorbidity, especially in patients undergoing long-term treatment with high doses of bisphosphonates. The management of BRONJ remains controversial. Surgical treatment is necessary in severe cases. Treatment of the bone requires sequestrectomy or resection. Given the lack of sufficient mucosa to perform the operation and fragility of margins in many patients, local flaps are crucial. We report two cases of stage-3 BRONJ presenting secondary infection with Actinomyces, receiving treatment consisting of marginal resection of the necrotic bone, reinforcement with a reconstruction plate, and reconstruction of soft tissues using a submental perforator artery flap ipsilateral to the lesion. Total cure was achieved in both cases, achieving favorable aesthetic and functional outcomes.

Bisphosphonates are anti–bone resorptive drugs which have been used to treat different diseases and conditions with increased bone resorption.[1,2,3,4,5,6] Since 2003, bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) has emerged as an important comorbidity, especially in patients treated with high doses of bisphosphonates over an extended period of time.[1,3,4,7] The risk factors for BRONJ include high doses of intravenous aminobisphosphonate, intravenous treatment for cancer (compared with those treated orally), smoking, concomitant treatment with immunosuppressive and/or chemotherapy drugs, invasive dental procedures, oral infections, mechanical trauma to the jawbone, and long-term treatment for bisphosphonates.[2,4,8]

The American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons recommends suspicion BRONJ if all of the following three characteristics are present: current or previous treatment with a bisphosphonate, exposed bone in the maxillofacial region persisting for more than 8 weeks, and no history of radiation therapy to the jaws.[4]

Four clinical stages of BRONJ have been established:

- Step 0: No clinical evidence of necrotic bone, but nonspecific clinical findings and symptoms

- Step 1: Exposed and necrotic bone in asymptomatic patients without evidence of infection

- Step 2: Exposed and necrotic bone associated with infection as evidenced by pain and erythema in region of exposed bone with or without purulent drainage

- Step 3: Exposed and necrotic bone in patients with pain, infection, and one or more of the following: exposed and necrotic bone extending beyond the region of the alveolar bone (i.e., inferior border and ramus in the mandible, maxillary sinus, and zygoma in the maxilla) resulting in pathologic fracture, extraoral fistula, oral antral/oral nasal communication, or osteolysis extending to the inferior border of the mandible or the sinus floor.[4]

The management of BRONJ remains controversial.[1,2,3,5,7,9] Surgical treatment is necessary in severe cases of BRONJ. Surgery may range from sequestrectomy to resection of the affected bone in the mandible or maxilla.[3,10] The gold standard treatments for stage 3 and advanced stage 2 diseases are surgical removal of necrotic bone tissue, a sufficient tension-free wound closure with a mucoperiosteal flap, and intravenous antibiotic treatment.[3,6,10]

As there is mostly a lack of sufficient mucosa and fragility of margins, local flaps are crucial.[11,12] Some authors defend the use of local flaps—especially for resistant cases—in advanced stages of the disease.[2,10,12,13]

Based on the submental artery, the submental flap is a reliable option in facial reconstruction.[14,15,16,17,18,19,20] The flap was first described by Martin[15] in 1993. The perforator submental flap, which excludes the anterior belly of the digastric muscle, is a reliable technique described in the literature.[14]

We report two cases of stage 3 BRONJ presenting secondary infection with Actinomyces species and treated by performing marginal resection of the necrotic bone, reinforcement with a reconstruction plate, and reconstruction of soft tissues using a submental perforator flap ipsilateral to the lesion.

Clinical Cases

Case 1

A 64-year-woman presented to our hospital with exposed bone with purulent discharge on the lingual surface of the left mandibular third molar and paresthesia of the inferior alveolar nerve. She had received intravenous zoledronic acid every 3 months over a 3-year period due to bone metastasis following primary carcinoma of the breast, and had undergone extraction of her left mandibular third molar 1 year before. Computed tomography (CT) images revealed a sclerotic lesion measuring 35 mm in diameter at its widest point, located in the posterior mandibular body extending from the left mandibular second molar to the mandibular ramus, with areas of heterogeneous osteolytic lesions on the medullary and lingual cortical bone.

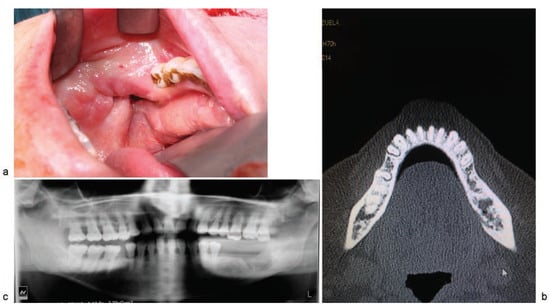

Figure 1.

(a) Exposed bone on the lingual side of the left posterior mandibular body; (b) computed-tomography image showing peripheral sclerosis with lysis of the medullary and lingual cortical bone of the posterior region of the left mandibular body; (c) panoramic radiograph images revealing low bone density with areas of sequestration in the left posterior mandibular body and including the mandibular canal.

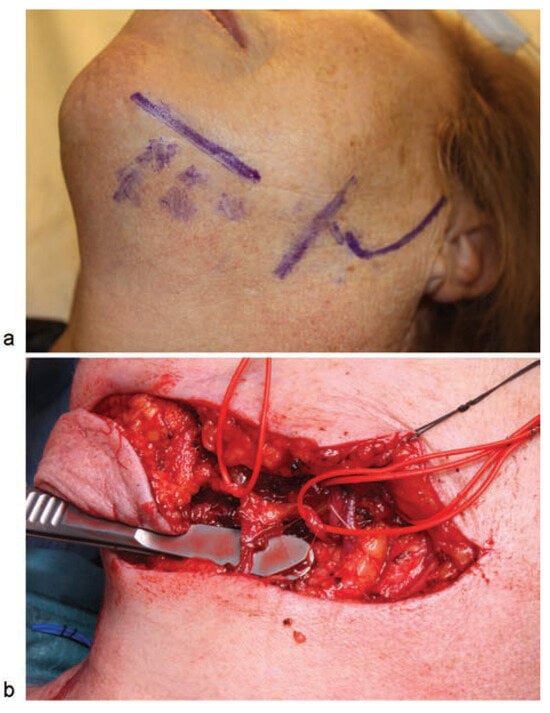

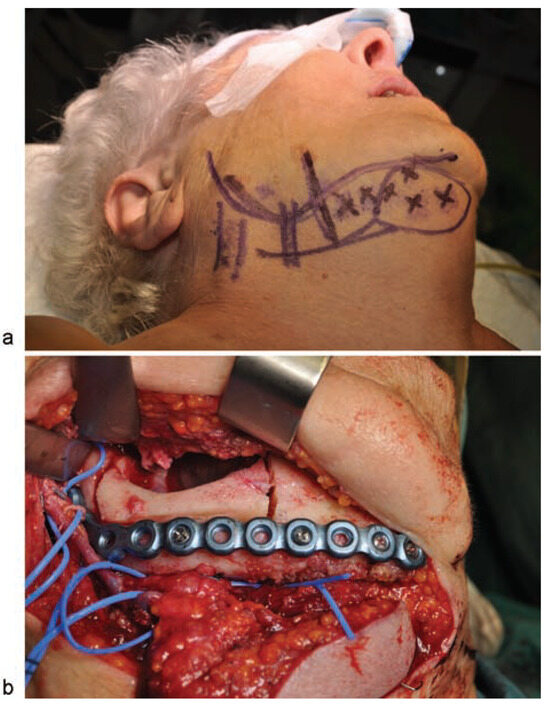

Figure 2.

(a) Perforator marking: The transverse line shows the inferior border of the mandibular body. The anterior vertical line indicates the facial artery. The perforators are marked with the letter “x”; (b) The harvested skin paddle. The submental vein is shown below the handle of the tissue forceps at the site where the vein connects with the submental artery and venae comitantes (vessel loop posterior), thereby producing a perforator with branches of the submental artery and vein (vessel loop anterior).

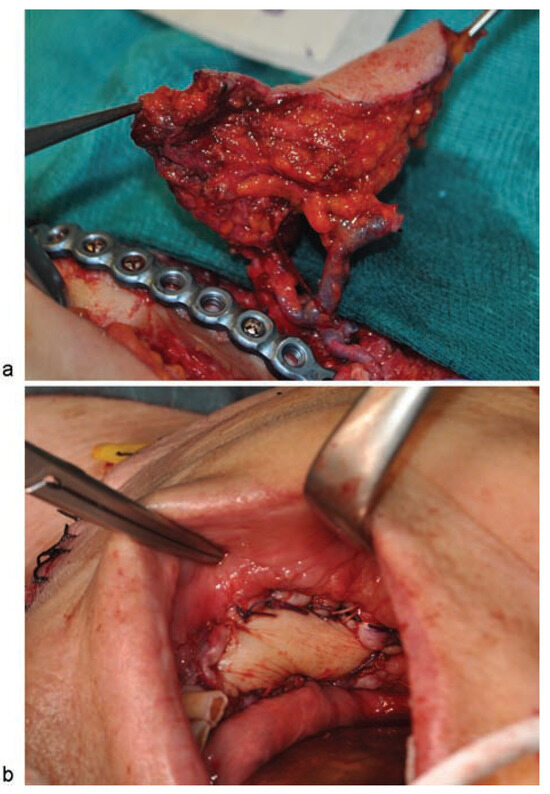

Figure 3.

(a) Surgical approach via the neck showing facial vessels (vessel loop posterior), marginal mandibulectomy, before removal of resected bone, and a 2.0-mm reconstruction plate to reinforce the mandible; (b) image showing the wide flap radius, with no need for facial vessels section; (c) submental flap covering the treated bone and tunneled through the lingual surface of the mandible.

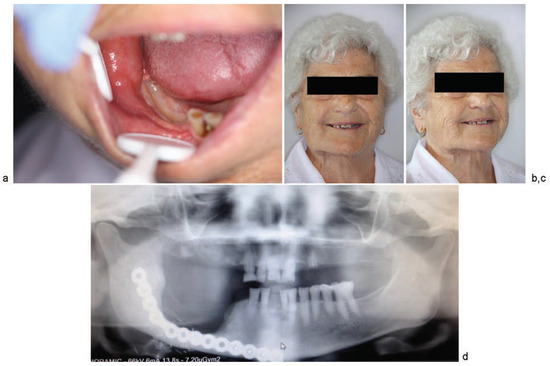

Figure 4.

5 months postoperatively: (a) appearance of the oral cavity, including the submental flap; (b) anterior view; (c) 3/4 left view; (d) panoramic radiograph image.

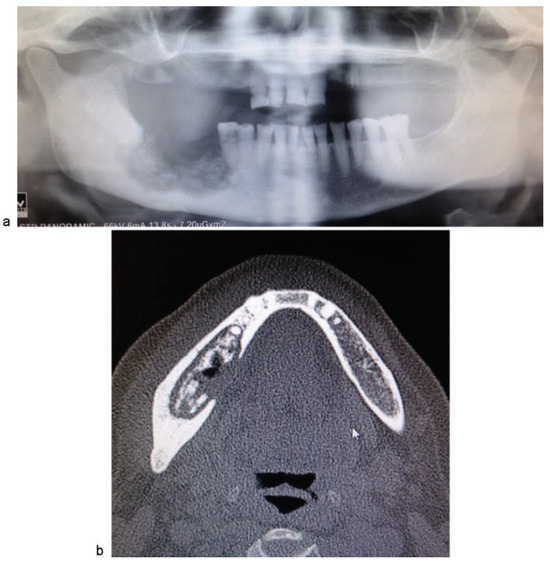

Figure 5.

(a) Panoramic radiograph image in which low bone density and areas containing sequestra appear between the right mandibular second premolar and the ramus, including involvement of mandibular canal; (b) computed tomography image in which a lesion can be seen in the posterior right mandibular body, with peripheral sclerosis, and sequestration of the medullary and the lingual cortical bone.

Seven months after completing treatment with zoledronic acid, the patient underwent the first surgical procedure under general anesthesia. The left mandibular second molar was extracted, the bone sequestra were resected, and then curettage was performed on the necrotic bone until healthy bone was reached. Following this, a buccal fat pad flap was raised to cover the treated bone, and a vestibular mucosal flap was placed on top of the fat pad flap for closure of the wound.

A histopathology study revealed histologic changes compatible with osteonecrosis in association with clusters belonging to the Actinomyces spp.

Antibiotic therapy consisting of amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (500–125 mg) every 8 hours was prescribed. Two months after surgery, the patient presented with exposed alveolar bone in the area of the extraction socket with no purulent discharge (►Figure 1a). CT images evidenced a sclerotic lesion of the same size and in the same site as in the previous CT scan; the new osteolytic lesions were larger than the earlier ones, thus indicating progression of osteonecrosis (►Figure 1b, c).

The patient underwent a second surgical operation under general anesthesia and nasotracheal intubation, consisting of a transverse incision in the neck and harvesting of a submental perforator flap, including the submental vein and artery in the flap. The skin paddle measured 6 × 3 cm (►Figure 2). Using a surgical approach through the neck, marginal mandibulectomy was performed with a piezoelectric cutting tool, also removing the necrotic bone, after which the remaining bone was drilled until healthy bone was reached. The area was reconstructed using a 2.0-mm reconstruction plate from the mandibular ramus to the first left mandibular premolar to reinforce the basal bone (►Figure 3a). Finally, the submental flap was used to seal the site of the treated bone. It was not necessary to section the artery or the facial vein to augment the length of the pedicle (►Figure 3b, c). A nasogastric tube was inserted and remained in for 14 days. Antibiotic treatment was withdrawn 1 month postoperatively. At 7 months postoperatively, there were no signs of osteonecrosis, and the aesthetic and functional outcomes were favorable (►Figure 4a–d).

Case 2

An 81-year-old woman presented to our department with BRONJ of 3 years’ evolution. She had received oral treatment for osteoporosis, consisting of ibandronic acid over 1.5 years. She had stopped taking the drug following extraction of a molar in the fourth quadrant of the mouth 3 years prior.

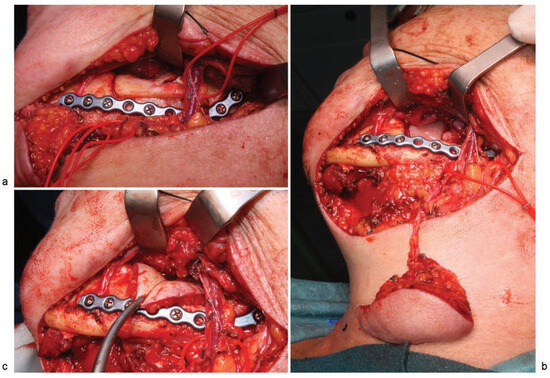

Figure 6.

(a) Flap design. Posterior vertical lines marking the veins of the neck, and anterior vertical lines signaling the facial vein (posterior) and facial artery (anterior). Perforators are marked with an “x.” A spindleshaped circle is used to mark the skin paddle situated at the center of the perforators; (b) image of the harvested submental flap. Marginal mandibulectomy before removal of the resected bone and insertion of the reconstruction plate used to reinforce the remaining bone.

An oral examination revealed purulent discharge and exposed bone on the lingual surface of the area of the right molars and paresthesia of inferior alveolar nerve.

Imaging studies revealed a wide sclerotic lesion measuring 6.3 cm at its widest point, extending from the right mandibular ramus to the right mandibular second premolar, including the mandibular canal. Most of the lingual cortical bone had disappeared, and a bone sequestrum of 3 cm at its widest point was observed (►Figure 5a, b).

A biopsy of the bone sequestrum was performed, revealing histologic changes consistent with osteonecrosis associated with clusters belonging to the Actinomyces spp.

With the patient under general anesthesia and following nasotracheal intubation, a submental perforator flap with a skin island of 4 × 3 cm was raised (►Figure 6a). A marginal mandibulectomy of the mandibular ramus and body was performed using a piezoelectric cutting tool. All necrotic bone was resected, preserving a portion of the mandibular basal bone. To reinforce the mandibular bone, a 2.4-mm reconstruction plate was inserted, extending from the right mandibular ramus to the symphysis (►FFigure 6b). Finally, the submental flap was used to seal the defect in the oral mucosa and cover the treated bone (►Figure 7a, b). There was no need to sacrifice the facial vessels for the sake of pedicle size, as the area to be reconstructed lies along the submental artery axis. A nasogastric tube was inserted and remained in for 23 days. Following surgery, the patient was administered antibiotic therapy (amoxicillin + clavulanic acid, 500–125 mg) over a period of 16 days. At 17 months postoperatively, there were no signs or symptoms of osteonecrosis, and the aesthetic and functional outcomes were favorable (►Figure 8a–d).

Figure 7.

(a) Image of the submental flap showing the inclusion of another vein in addition to the submental vein to improve venous return; the submental vein is joined to the submental artery; (b) image of the oral cavity after the flap was sutured.

Discussion

Several theories on the pathogenesis of BRONJ have appeared in the literature, mostly focusing on osteoclast inhibition, antiangiogenic processes, mucosal toxicity, and cytokine-mediated inflammation.[1,6,8,9,13,21] However, the exact mechanisms need further investigation.[1,3,6,8,10,21,22]

Given the long average life of bisphosphonates in bone, some authors consider it unnecessary to withdraw them before surgical treatment of BRONJ. Others, however, report a reduction in symptoms and reduced risk of new sites of BRONJ when they are withdrawn.[3,4,6,10] For patients with cancer, oncologists and maxillofacial surgeons together must perform a risk–benefit analysis for each case when considering suspension of treatment.[3,4,6,10] In the two cases presented here, biphosphonate treatment was withdrawn.

Figure 8.

13 months postoperatively: (a) appearance of the oral cavity; (b) anterior image; (c) (3/4 right view); (d) panoramic radiograph image.

Some studies have hypothesized that bacteria belonging to the Actinomyces genus may play an important role in BRONJ.[13,23] The two cases presented exhibited infection with species belonging to the Actinomyces genus.

Surgical treatment of BRONJ requires proper resection of necrotic bone as well as adequate coverage of soft tissues, and success rates are higher the earlier treatment is performed.[10,11,12,13]

To treat BRONJ of the mandible, Lemound et al first resected the necrotic bone and then used a flap made from the mylohyoid muscle to cover the healthy muscle. This muscle was later covered by the oral mucosa. Good results are achieved when BRONJ is treated while in stages I and II.[3] The approach taken by Voss et al, called multiple-layered wound closure, uses both conventional closure of the mucosa and harvesting of a periosteal flap, achieving complete recovery of the mucosa in 95.2% of patients with BRONJ.[13]

Other authors have used a pedicled buccal fat pad flap to cover treated bone, obtaining good results.[12] In the first case described here, we used a pedicled buccal fat pad flap to cover the treated bone, though with suboptimal results.

The submental flap allows us to access large amounts of wellvascularized skin and subcutaneous cell tissue without the need for a microsurgical free flap. The donor site is in the neck, and the only sequel is a transverse scar in the area of the neck; however, other types of flaps would cause this same surgical scarring because of the need to approach the surgical site through the neck in order for the marginal mandibulectomy to be well controlled and also to insert the reconstruction plate. It is a rather reliable and straightforward type of flap, although when performed to treat cases of BRONJ, the existence of a chronic infection adjacent to the submental vessels adds complication to the harvest of the flap.[14,15,16,17,18,19,20] Damage to the marginal branch of the facial nerve is one of the possible consequences of raising this flap, and this complication occurs in up to 16% of cases. This undesired outcome may be avoided by locating the nerve during the procedure.[14] In male patients, another difficulty of this flap is translocation of hair-bearing skin.[14,19]

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank Oliver Shaw (IIS-FJD) for editing the manuscript for aspects related to the English language.

References

- Barba-Recreo, P.; Del Castillo Pardo de Vera, J.L.; García-Arranz, M.; Yébenes, L.; Burgueño, M. Zoledronic acid - related osteonecrosis of the jaws. Experimental model with dental extractions in rats. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2014, 42, 744–750. [Google Scholar]

- Barba-Recreo, P.; Del Castillo Pardo de Vera, J.L.; Georgiev-Hristov, T.; et al. Adipose-derived stem cells and platelet-rich plasma for preventive treatment of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw in a murine model. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 1161–1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lemound, J.; Eckardt, A.; Kokemüller, H.; et al. Bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the mandible: reliable soft tissue reconstruction using a local myofascial flap. Clin Oral Investig 2012, 16, 1143–1152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Assael, L.A.; Landesberg, R.; Marx, R.E.; Mehrotra, B.; American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws—2009 update. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 67 (Suppl 5), 2–12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fliefel, R.; Tröltzsch, M.; Kühnisch, J.; Ehrenfeld, M.; Otto, S. Treatment strategies and outcomes of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) with characterization of patients: a systematic review. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015, 44, 568–585. [Google Scholar]

- Jabbour, Z.; El-Hakim, M.; Mesbah-Ardakani, P.; Henderson, J.E.; Albuquerque, R., Jr. The outcomes of conservative and surgical treatment of stage 2 bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: a case series. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2012, 41, 1404–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marx, R.E. Pamidronate (Aredia) and zoledronate (Zometa) induced avascular necrosis of the jaws: a growing epidemic. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2003, 61, 1115–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, L.W.; Hsiao, S.H.; Chen, L.K. Clinical treatment outcomes for 40 patients with bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. J Formos Med Assoc 2014, 113, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, T.; Kuraguchi, J.; Kogashiwa, Y.; Yokoi, H.; Satomi, T.; Kohno, N. Successful treatment of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ) patients with sitafloxacin: new strategies for the treatment of BRONJ. Bone 2015, 73, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton, D.C.; Balasanian, E. Outcome of surgical management of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws: review of 33 surgical cases. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2009, 67, 943–950. [Google Scholar]

- Reich, W.; Bilkenroth, U.; Schubert, J.; Wickenhauser, C.; Eckert, A.W. Surgical treatment of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis: Prognostic score and long-term results. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2015, 43, 1809–1822. [Google Scholar]

- Rotaru, H.; Kim, M.K.; Kim, S.G.; Park, Y.W. Pedicled buccal fat pad flap as a reliable surgical strategy for the treatment of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2015, 73, 437–442. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Voss, P.J.; Joshi Oshero, J.; Kovalova-Müller, A.; et al. Surgical treatment of bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: technical report and follow up of 21 patients. J Craniomaxillofac Surg 2012, 40, 719–725. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.T. Morris, S.F., Hallock, G.G., Neligan, P.C., Eds.; Submental artery perforator flap. In Perforator Flaps: Anatomy, Technique, and Clinical Applications; Quality Medical Publishing, Inc.: St. Louis, MO, USA, 2006; Volume 1, pp. 161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, D.; Pascal, J.F.; Baudet, J.; et al. The submenta island flap: a new donor site. Anatomy and clinical applications as a free or pedicled flap. Plast Reconstr Surg 1993, 92, 867–873. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.L.; Ye, J.T.; Yang, Z.H.; Huang, Z.Q.; Zhang, D.M.; Wang, K. Reverse facial artery-submental artery mandibular osteo muscular flap for the reconstruction of maxillary defects following the removal of benign tumors. Head Neck 2009, 31, 725–731. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.H.; Chen, W.L.; Wang, Y.P.; Liang, J.; Zhang, D.M. Reverse facial-submental artery island flap for the reconstruction of maxillary defects after cancer ablation. J Craniofac Surg 2009, 20, 2217–2220. [Google Scholar]

- You, Y.H.; Chen, W.L.; Wang, Y.P.; Liang, J. The feasibility of facial-submental artery island myocutaneous flaps for reconstructing defects of the oral floor following cancer ablation. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2010, 109, e12–e16. [Google Scholar]

- Jeong, S.H.; Lee, B.I. Versatile use of submental tissue for reconstruction of perioral soft tissue defects. J Craniofac Surg 2012, 23, 934–938. [Google Scholar]

- Amin, A.A.; Sakkary, M.A.; Khalil, A.A.; Rifaat, M.A.; Zayed, S.B. The submental flap for oral cavity reconstruction: extended indications and technical refinements. Head Neck Oncol 2011, 3, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Rupel, K.; Ottaviani, G.; Gobbo, M.; et al. A systematic review of therapeutical approaches in bisphosphonates-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (BRONJ). Oral Oncol 2014, 50, 1049–1057. [Google Scholar]

- Otto, S.; Schreyer, C.; Hafner, S.; et al. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws characteristics, risk factors, clinical features, localization and impact on oncological treatment. J Cranio maxillofac Surg 2012, 40, 303–309. [Google Scholar]

- Arranz Caso, J.A.; Flores Ballester, E.; Ngo Pombe, S.; López Pizarro, V.; Dominguez-Mompello, J.L.; Restoy Lozano, A. Bisphosphonate related osteonecrosis of the jaw and infection with Actinomyces [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc) 2012, 139, 676–680. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the author. The Author(s) 2016.