Organizational Ambidexterity: How Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Activity-Based Costing (ABC) Enable Exploration–Exploitation Synergy and Sustainable Performance

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses Development

2.1. Theoretical Background

2.1.1. Organizational Ambidexterity

2.1.2. Balanced Scorecard

2.1.3. Activity-Based Costing

2.1.4. Recent Developments and Extensions

2.2. Hypotheses Development

3. Methodology

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Sample and Data

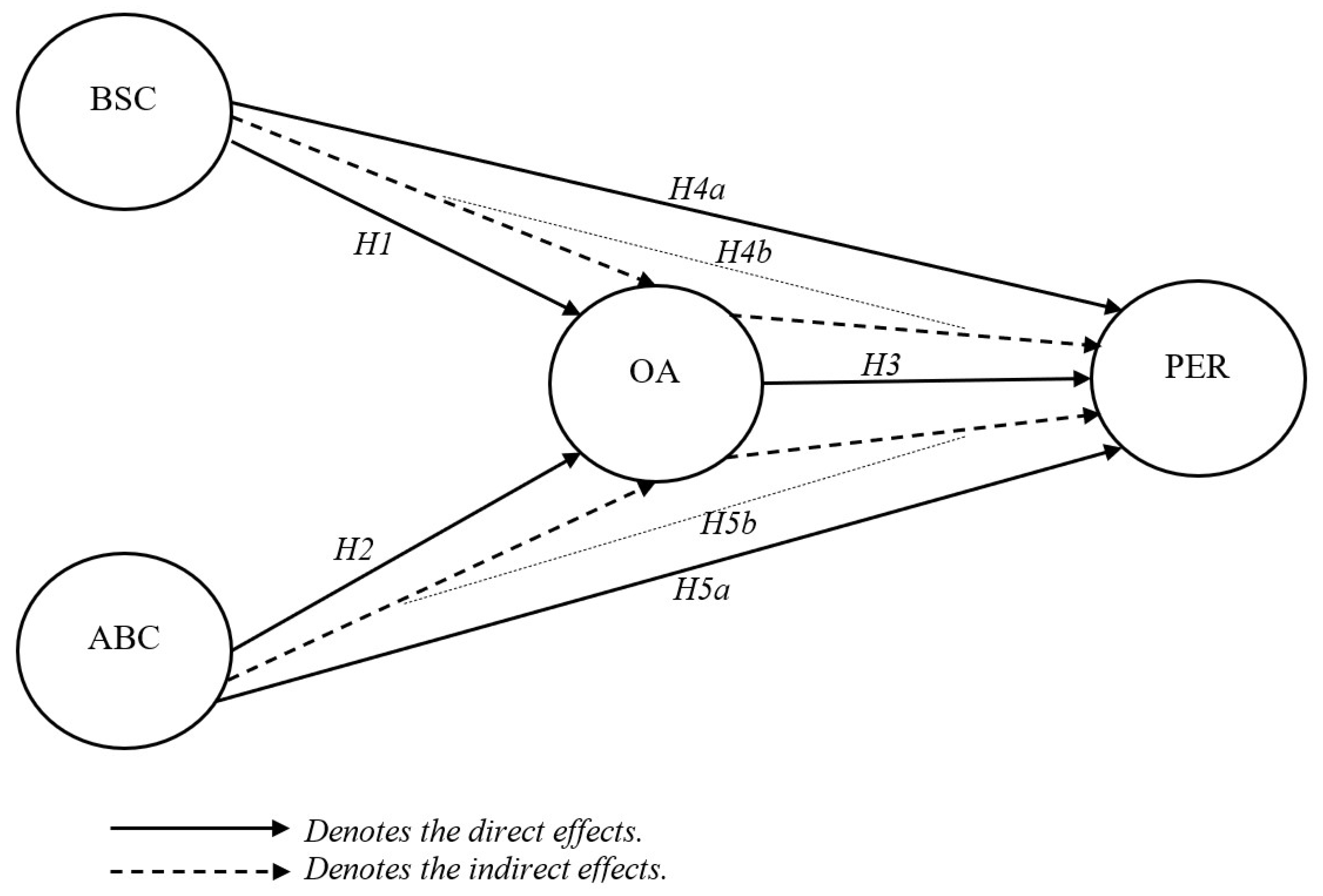

3.3. Path Model

- (i)

- OA = β0 + β1BSC + β2ABC + ℇ

- (ii)

- PER = β0 + β1BSC + β2ABC + β3OA + ℇ

- OA = Organizational ambidexterity;

- BSC = Balanced scorecard;

- ABC = Activity-based costing;

- PER = Organizational performance;

- β0 = Constant term;

- β1, β2, β3 = Regression coefficients;

- ε = Error term.

4. Results

4.1. Measures Validation

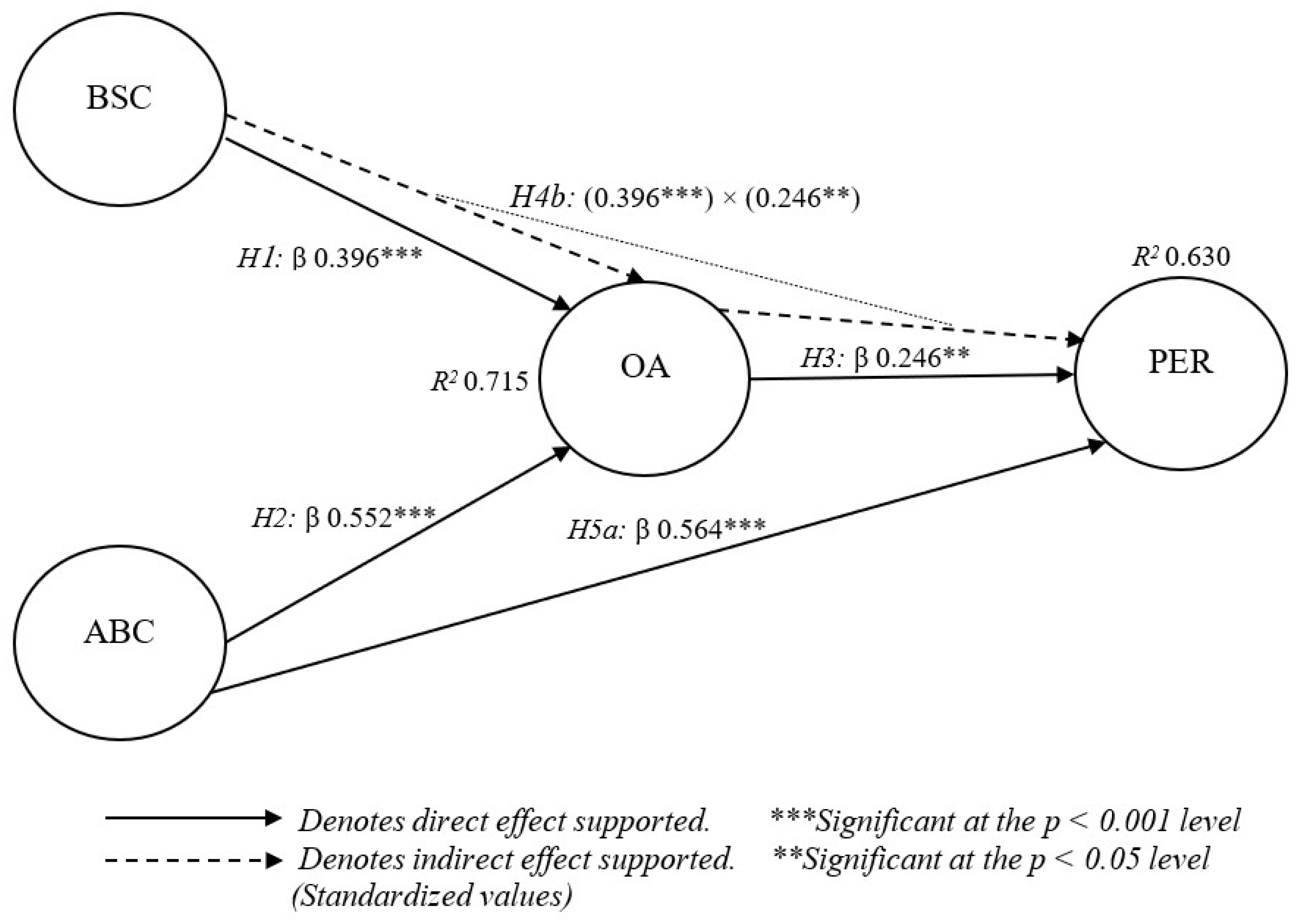

4.2. Results of the Structural Model and Hypothesis Testing

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

6.1. Theoretical Implications

6.2. Practical Implications

6.3. Limitations and Future Studies

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abernethy, M. A., & Lillis, A. M. (1995). The impact of manufacturing flexibility on management control system design. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 20(4), 241–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhubaibi, A. A. S. (2024). Unveiling the mediating effect of intellectual capital on the relationship between management control system, management accounting, and business performance. International Journal of Mathematical, Engineering and Management Sciences, 9(4), 844–864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dhubaibi, A. A. S., Sanusi, Z. M., Hasnan, S., & Yusuf, S. N. S. (2023). The association between management accounting advancement and corporate performance: An application of IFAC conception for management accounting evolution. Quality-Access to Success, 24(195), 272–279. [Google Scholar]

- Appelbaum, D., Kogan, A., Vasarhelyi, M., & Yan, Z. (2017). Impact of business analytics and enterprise systems on managerial accounting. International Journal of Accounting Information Systems, 25, 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banker, R. D., Bardhan, I. R., & Chen, T.-Y. (2008). The role of manufacturing practices in mediating the impact of activity-based costing on plant performance. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisbe, J., & Malagueño, R. (2012). Using strategic performance measurement systems for strategy formulation: Does it work in dynamic environments? Management Accounting Research, 23(4), 296–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bocken, N. M., Ritala, P., & Huotari, P. (2017). The circular economy: Exploring the introduction of the concept among S&P 500 firms (Vol. 21, pp. 487–490). Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Braam, G. J., & Nijssen, E. J. (2004). Performance effects of using the balanced scorecard: A note on the Dutch experience. Long Range Planning, 37(4), 335–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cagwin, D., & Bouwman, M. J. (2002). The association between activity-based costing and improvement in financial performance. Management Accounting Research, 13(1), 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., & Halevi, M. Y. (2009). How top management team behavioral integration and behavioral complexity enable organizational ambidexterity: The moderating role of contextual ambidexterity. The Leadership Quarterly, 20(2), 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chehimi, M., & Naro, G. (2024). Balanced scorecards and sustainability balanced scorecards for corporate social responsibility strategic alignment: A systematic literature review. Journal of Environmental Management, 367, 122000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. H. (2005). Integrative strategic performance measurement systems, strategic alignment of manufacturing, learning and strategic outcomes: An exploratory study. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 30(5), 395–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chenhall, R. H., & Langfield-Smith, K. (1998). Adoption and benefits of management accounting practices: An Australian study. Management Accounting Research, 9(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, S., Venieris, G., & Kaimenaki, E. (2005). ABC: Adopters, supporters, deniers and unawares. Managerial Auditing Journal, 20(9), 981–1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooper, R., & Kaplan, R. S. (1988). Measure costs right: Make the right decisions. Harvard Business Review, 66(5), 96–103. [Google Scholar]

- Dağıdır, B. D., & Özkan, B. (2024). A comprehensive evaluation of a company performance using sustainability balanced scorecard based on picture fuzzy AHP. Journal of Cleaner Production, 435, 140519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Decoene, V., & Bruggeman, W. (2006). Strategic alignment and middle-level managers’ motivation in a balanced scorecard setting. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 26(4), 429–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dess, G. G., & Robinson, R. B. (1984). Measuring organizational performance in the absence of objective measures: The case of the privately-held firm and conglomerate business unit. Strategic Management Journal, 5(3), 265–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranev, Y., Izosimova, A., & Meissner, D. (2020). Organizational ambidexterity and performance: Assessment approaches and empirical evidence. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 11, 676–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drury, C., & Tayles, M. (1994). Product costing in UK manufacturing organizations. European Accounting Review, 3(3), 443–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duh, R. R., Lin, T. W., Wang, W. Y., & Huang, C. H. (2009). The design and implementation of activity-based costing: A case study of a Taiwanese textile company. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 17(1), 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabac, R. (2022). Digital balanced scorecard system as a supporting strategy for digital transformation. Sustainability, 14(15), 9690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gavrea, C., Ilies, L., & Stegerean, R. (2011). Determinants of organizational performance: The case of Romania. Management and Marketing, 6(2), 285–300. [Google Scholar]

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldratt, E. M., & Cox, J. (2016). The goal: A process of ongoing improvement. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T., & Figge, F. (2018). Why architecture does not matter: On the fallacy of sustainability balanced scorecards. Journal of Business Ethics, 150, 919–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis: Pearson new international edition. Pearson Education Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Havermans, L. A., Den Hartog, D. N., Keegan, A., & Uhl-Bien, M. (2015). Exploring the role of leadership in enabling contextual ambidexterity. Human Resource Management, 54(S1), s179–s200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.-L., & Wong, P.-K. (2004). Exploration vs. exploitation: An empirical test of the ambidexterity hypothesis. Organization Science, 15(4), 481–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henri, J.-F. (2006). Management control systems and strategy: A resource-based perspective. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(6), 529–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. (2008). Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53–60. [Google Scholar]

- Hoozée, S., & Bruggeman, W. (2010). Identifying operational improvements during the design process of a time-driven ABC system: The role of collective worker participation and leadership style. Management Accounting Research, 21(3), 185–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopper, T., & Major, M. (2007). Extending institutional analysis through theoretical triangulation: Regulation and activity-based costing in Portuguese telecommunications. European Accounting Review, 16(1), 59–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Z. (2014). 20 years of studies on the balanced scorecard: Trends, accomplishments, gaps and opportunities for future research. The British Accounting Review, 46(1), 33–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoque, Z., & James, W. (2000). Linking balanced scorecard measures to size and market factors: Impact on organizational performance. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 12(1), 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, I., Mohammed, A., Abdulaali, H. S., Mohammad, M. M., & Ali, K. (2023). Does digital balanced scorecards lead to the sustainable performance amongst the jordanian SMEs? International Journal of Professional Business Review, 8(7), 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inamdar, N., & Kaplan, R. S. (2002). Applying the balanced scorecard in healthcare provider organizations. Journal of Healthcare Management, 47(3), 179–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innes, J., & Mitchell, F. (1995). A survey of activity-based costing in the UK’s largest companies. Management Accounting Research, 6(2), 137–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C. D., Lanen, W. N., & Larcker, D. F. (2002). The association between activity-based costing and manufacturing performance. Journal of Accounting Research, 40(3), 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C. D., & Larcker, D. F. (2001). Assessing empirical research in managerial accounting: A value-based management perspective. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 349–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ittner, C. D., Larcker, D. F., & Randall, T. (2003). Performance implications of strategic performance measurement in financial services firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 28(7–8), 715–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. J., Tempelaar, M. P., Van den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2009). Structural differentiation and ambidexterity: The mediating role of integration mechanisms. Organization Science, 20(4), 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansen, J. J., Van Den Bosch, F. A., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory innovation, exploitative innovation, and performance: Effects of organizational antecedents and environmental moderators. Management Science, 52(11), 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junni, P., Sarala, R. M., Taras, V., & Tarba, S. Y. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity and performance: A meta-analysis. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 299–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jusoh, R., Nasir Ibrahim, D., & Zainuddin, Y. (2008). The performance consequence of multiple performance measures usage: Evidence from the Malaysian manufacturers. International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, 57(2), 119–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalista, A., Az-Zahro, S., & Wibowo, M. M. A. (2023). Designing key performance indicators based on the sustainable digital balanced scorecard for herbal medicine and cosmetic companies. In International conference on environment and sustainability. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Anderson, S. R. (2007). Time-driven activity-based costing: A simpler and more powerful path to higher profits. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Cooper, R. (1998). Cost & effect: Using integrated cost systems to drive profitability and performance. Harvard Business Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1992). The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1), 71–79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The balanced scorecard: Translating strategy into action. Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2001). Transforming the balanced scorecard from performance measurement to strategic management: Part 1. Accounting Horizons, 15(1), 87–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (2002). The strategy-focused organization: How balanced scorecard companies thrive in the new business environment (Vol. 2). Harvard Business School Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kasztelnik, K., & Campbell, S. (2023). The future of business data analytics and accounting automation. CPA Journal, 93(12/12), 60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Krumwiede, K. R. (1998). The implementation stages of activity-based costing and the impact of contextual and organizational factors. Journal of Management Accounting Research, 10, 239. [Google Scholar]

- Lavie, D., Stettner, U., & Tushman, M. L. (2010). Exploration and exploitation within and across organizations. Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 109–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maiga, A. S., & Jacobs, F. A. (2008). Extent of ABC use and its consequence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 25(2), 533–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- March, J. G. (1991). Exploration and exploitation in organizational learning. Organization Science, 2(1), 71–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Falcó, J., Sánchez-García, E., Marco-Lajara, B., & Lee, K. (2024). Green intellectual capital and environmental performance: Identifying the pivotal role of green ambidexterity innovation and top management environmental awareness. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 25(2/3), 380–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayo-Alvarez, L., Del-Aguila-Arcentales, S., & Alvarez-Risco, A. (2024). Innovation using dynamic balanced scorecard design as an industrial safety management system in a company in the mining metallurgical sector. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(3), 100362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mio, C., Costantini, A., & Panfilo, S. (2022). Performance measurement tools for sustainable business: A systematic literature review on the sustainability balanced scorecard use. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(2), 367–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newbert, S. L. (2008). Value, rareness, competitive advantage, and performance: A conceptual-level empirical investigation of the resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 29(7), 745–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niven, P. R. (2002). Balanced scorecard step-by-step: Maximizing performance and maintaining results. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Norreklit, H. (2000). The balance on the balanced scorecard a critical analysis of some of its assumptions. Management Accounting Research, 11(1), 65–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2004). The ambidextrous organization. Harvard Business Review, 82(4), 74–83. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2008). Ambidexterity as a dynamic capability: Resolving the innovator’s dilemma. Research in Organizational Behavior, 28, 185–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, C. A., & Tushman, M. L. (2013). Organizational ambidexterity: Past, present, and future. The Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 324–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, P. C., Messersmith, J. G., & Lepak, D. P. (2013). Walking the tightrope: An assessment of the relationship between high-performance work systems and organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1420–1442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, M. Y.-P., Lin, K.-H., Peng, D. L., & Chen, P. (2019). Linking organizational ambidexterity and performance: The drivers of sustainability in high-tech firms. Sustainability, 11(14), 3931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J.-Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raisch, S., & Birkinshaw, J. (2008). Organizational ambidexterity: Antecedents, outcomes, and moderators. Journal of Management, 34(3), 375–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robert, G., & George, S. (2013). The performance frontier: Innovating for a sustainable strategy. Harvard Business Review, 91, 50–60. [Google Scholar]

- Sayed, S., & Dayan, M. (2024). The impact of managerial autonomy and founding-team marketing capabilities on the relationship between ambidexterity and innovation performance. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 10(1), 100238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharaf-Addin, H. H., & Al-Dhubaibi, A. A. S. (2025). Carbon sustainability reporting based on GHG protocol framework: A Malaysian practice towards net-zero carbon emissions. Environmental and Sustainability Indicators, 25, 100588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sierra, H. L., & Mila, M. I. P. (2025). The ambidextrous scorecard: A strategic tool for balancing exploitation and exploration in the hospitality sector. DYNA: Revista De La Facultad De Minas. Universidad Nacional de Colombia. Sede Medellín, 92(236), 81–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Speckbacher, G., Bischof, J., & Pfeiffer, T. (2003). A descriptive analysis on the implementation of balanced scorecards in German-speaking countries. Management Accounting Research, 14(4), 361–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tayles, M., Pike, R. H., & Sofian, S. (2007). Intellectual capital, management accounting practices and corporate performance: Perceptions of managers. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 20(4), 522–548. [Google Scholar]

- Tsamenyi, M., Sahadev, S., & Qiao, Z. S. (2011). The relationship between business strategy, management control systems and performance: Evidence from China. Advances in Accounting, 27(1), 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, N., & Lee-Kelley, L. (2013). Unpacking the theory on ambidexterity: An illustrative case on the managerial architectures, mechanisms and dynamics. Management Learning, 44(2), 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turney, P. B. B. (1996). Activity based costing: The performance breakthrough. Kogan. Available online: https://cir.nii.ac.jp/crid/1130282272297174656 (accessed on 18 August 2024.).

- Tushman, M. L., & O’Reilly, C. A. (1996). Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change. California Management Review, 38(4), 8–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Úbeda-García, M., Marco-Lajara, B., Zaragoza-Sáez, P. C., Manresa-Marhuenda, E., & Poveda-Pareja, E. (2022). Green ambidexterity and environmental performance: The role of green human resources. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(1), 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wall, T. D., Michie, J., Patterson, M., Wood, S. J., Sheehan, M., Clegg, C. W., & West, M. (2004). On the validity of subjective measures of company performance. Personnel Psychology, 57(1), 95–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource-based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, E. J., Harrington, K. M., Clark, S. L., & Miller, M. W. (2013). Sample size requirements for structural equation models: An evaluation of power, bias, and solution propriety. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(6), 913–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ylinen, M., & Gullkvist, B. (2014). The effects of organic and mechanistic control in exploratory and exploitative innovations. Management Accounting Research, 25(1), 93–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yousef, H., & Sponem, S. (2025). The adoption of management accounting innovations in emerging economies: Exploring market, institutional and organizational factors. Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Construct | Absolute Fit | Incremental Fit | Parsimonious Fit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GFI (>0.90) | CFI (>0.90) | TLI (>0.90) | NFI (>0.90) | ChiSq/df (<5.0) | |

| Balanced Scorecard | 0.975 | 0.993 | 0.982 | 0.989 | 3.041 |

| Activity-Based Costing | 0.940 | 0.974 | 0.951 | 0.966 | 4.256 |

| Organizational Ambidexterity | 0.950 | 0.975 | 0.963 | 0.959 | 2.438 |

| Performance | 0.948 | 0.979 | 0.963 | 0.970 | 3.129 |

| Balanced Scorecard | Activity-Based Costing | Organizational Ambidexterity | Performance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Scorecard | 0.909 | |||

| Activity-Based Costing | 0.580 | 0.849 | ||

| Organizational Ambidexterity | 0.716 | 0.782 | 0.784 | |

| Performance | 0.537 | 0.776 | 0.711 | 0.842 |

| Construct | Item | Factor Loading (>0.6) | R2 (>0.4) | Cronbach Alpha (>0.7) | CR (>0.6) | AVE (>0.5) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Scorecard | BSC_1 | 0.88 | 0.77 | 0.961 | 0.960 | 0.827 |

| BSC_2 | 0.85 | 0.72 | ||||

| BSC_3 | 0.93 | 0.86 | ||||

| BSC_4 | 0.97 | 0.94 | ||||

| BSC_5 | 0.92 | 0.85 | ||||

| Activity-Based Costing | ABC_1 | 0.89 | 0.78 | 0.936 | 0.939 | 0.720 |

| ABC_2 | 0.87 | 0.75 | ||||

| ABC_3 | 0.92 | 0.84 | ||||

| ABC_4 | 0.89 | 0.80 | ||||

| ABC_5 | 0.83 | 0.69 | ||||

| ABC_6 | 0.69 | 0.47 | ||||

| Organizational Ambidexterity | OA_1 | 0.79 | 0.62 | 0.913 | 0.916 | 0.610 |

| OA_2 | 0.65 | 0.43 | ||||

| OA_3 | 0.82 | 0.68 | ||||

| OA_4 | 0.70 | 0.49 | ||||

| OA_5 | 0.84 | 0.71 | ||||

| OA_6 | 0.75 | 0.57 | ||||

| OA_7 | 0.88 | 0.78 | ||||

| Performance | PER_1 | 0.76 | 0.57 | 0.944 | 0.944 | 0.710 |

| PER_2 | 0.81 | 0.65 | ||||

| PER_3 | 0.88 | 0.77 | ||||

| PER_4 | 0.95 | 0.90 | ||||

| PER_5 | 0.86 | 0.75 | ||||

| PER_6 | 0.90 | 0.81 | ||||

| PER_7 | 0.73 | 0.53 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Standardized Estimate | Regression Estimate | S.E. | C.R. | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Structural Model with Direct Effects (Pre-Mediation Effects) | |||||||

| Balanced Scorecard | ➔ | Performance | 0.129 | 0.111 | 0.055 | 2.018 | 0.044 |

| Activity-Based Costing | ➔ | Performance | 0.701 | 0.71 | 0.083 | 8.527 | *** |

| Final Structural Model (After Incorporating the Mediator) | |||||||

| Balanced Scorecard | ➔ | Organizational Ambidexterity | 0.396 | 0.314 | 0.051 | 6.183 | *** |

| Activity-Based Costing | ➔ | Organizational Ambidexterity | 0.552 | 0.517 | 0.065 | 7.974 | *** |

| Balanced Scorecard | ➔ | Performance | 0.033 | 0.029 | 0.064 | 0.448 | 0.654 |

| Activity-Based Costing | ➔ | Performance | 0.564 | 0.573 | 0.098 | 5.841 | *** |

| Organizational Ambidexterity | ➔ | Performance | 0.246 | 0.266 | 0.117 | 2.279 | 0.023 |

| Hypothesized Paths | Direct Effect Before Mediation | Direct Effect After Mediation | Indirect Effect | Test of Mediation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BSC | ---------> | PER | 0.129 ** | 0.033 | Full Mediation | |||

| BSC | ---> | OA | ---> | PER | (0.396 ***) × (0.246 **) = 0.097 | |||

| ABC | ---------> | PER | 0.701 *** | 0.564 *** | No Mediation | |||

| ABC | ---> | OA | ---> | PER | (0.552 ***) × (0.246 **) = 0.136 | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Al-Dhubaibi, A.A.S. Organizational Ambidexterity: How Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Activity-Based Costing (ABC) Enable Exploration–Exploitation Synergy and Sustainable Performance. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090508

Al-Dhubaibi AAS. Organizational Ambidexterity: How Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Activity-Based Costing (ABC) Enable Exploration–Exploitation Synergy and Sustainable Performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(9):508. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090508

Chicago/Turabian StyleAl-Dhubaibi, Ahmed Abdullah Saad. 2025. "Organizational Ambidexterity: How Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Activity-Based Costing (ABC) Enable Exploration–Exploitation Synergy and Sustainable Performance" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 9: 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090508

APA StyleAl-Dhubaibi, A. A. S. (2025). Organizational Ambidexterity: How Balanced Scorecard (BSC) and Activity-Based Costing (ABC) Enable Exploration–Exploitation Synergy and Sustainable Performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(9), 508. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18090508