3. Methodology

The empirical analysis utilises a balanced panel dataset comprising 41 countries over the period from 2019 to 2024. As the original dataset included only 27 countries with complete observations, it was expanded through data harmonization and the application of multiple imputation techniques. Specifically, Predictive Mean Matching (PMM) was employed in R to address missing values. PMM was selected for its ability to draw imputed values from the observed data distribution, thereby preserving the empirical properties of the adoption variable. This approach improves data integrity, enhances the generalizability of the results, and mitigates distortion across country contexts.

The analysis incorporates a set of economic risk indicators, namely inflation, unemployment, and exchange rate volatility, alongside structural control variables including GDP per capita, internet penetration, and regulatory permissiveness. These variables were sourced from reputable international databases, including the World Bank, Statista, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the Vision of Humanity, and Transparency International. Prior to estimation, all variables were standardised using z-scores to facilitate comparability and ensure scale invariance. The primary analytical technique is a country fixed-effects regression model, which accounts for time-invariant heterogeneity across countries, capturing persistent macroeconomic and institutional differences that could otherwise bias estimates. To address potential issues of serial correlation and cross-sectional dependence, robust standard errors were calculated using the Driscoll–Kraay method. Additionally, Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was employed to mitigate multicollinearity and uncover latent structures among the explanatory variables. By condensing highly correlated indicators into orthogonal components, PCA enables clearer identification of the dominant risk dimensions associated with cryptocurrency adoption.

3.1. Data Rationale

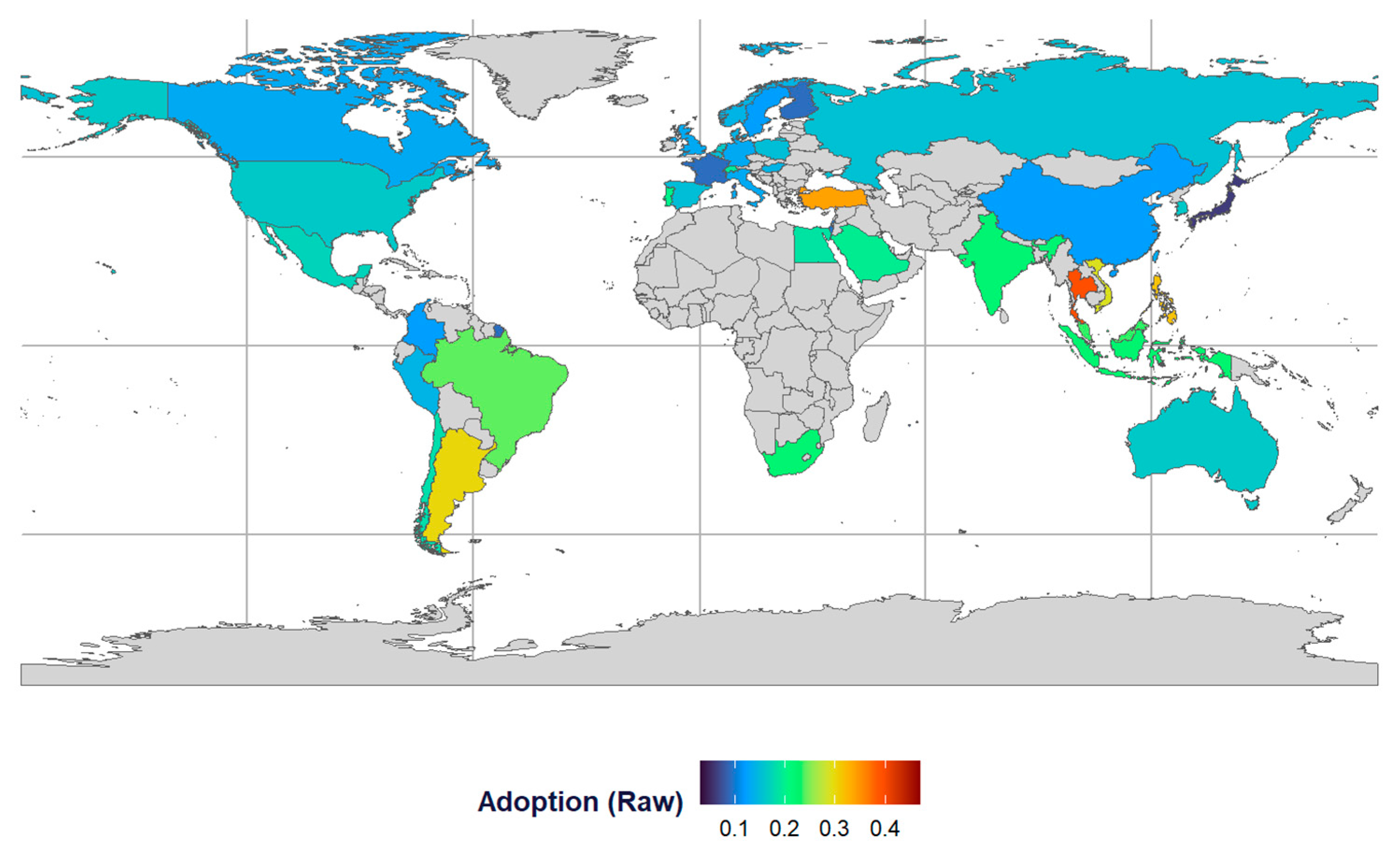

A balanced panel dataset comprising 41 countries from 2019 to 2024 was constructed for the empirical analysis (

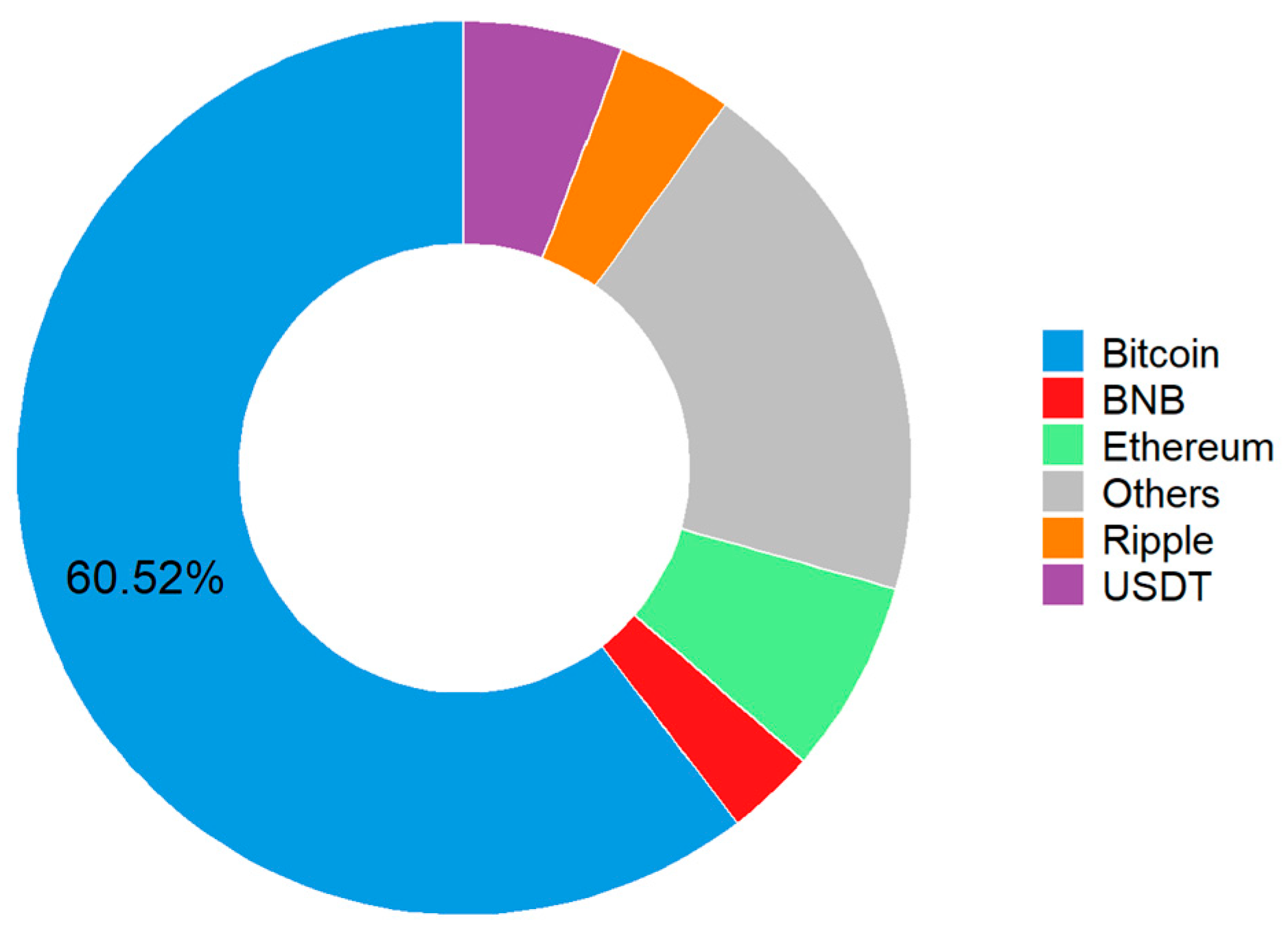

Appendix A provides the full list of countries). The dependent variable, cryptocurrency adoption, is defined as the proportion of individuals within a country who report owning or using digital currencies such as Bitcoin or Ethereum. This measure is drawn from Statista’s Global Consumer Survey, offering self-reported adoption rates across countries. As illustrated in

Figure 3, the “raw” adoption rates capture the original, untransformed percentage of the population using cryptocurrency. This indicator was selected for its granularity and its ability to reflect adoption at the household level.

The 41 countries included were selected based on the availability of complete data across key variables for the 2019 to 2024 period, including cryptocurrency adoption rates, CPI scores, inflation, unemployment, exchange rate volatility, GDP per capita, internet penetration, and regulatory status. Countries with missing or inconsistent data across more than two of these indicators were excluded to ensure comparability and the reliability of statistical inferences. The final sample includes a diverse mix of developed and developing economies, high-adoption and low-adoption contexts, and varying regulatory environments, allowing for a globally representative and analytically balanced dataset.

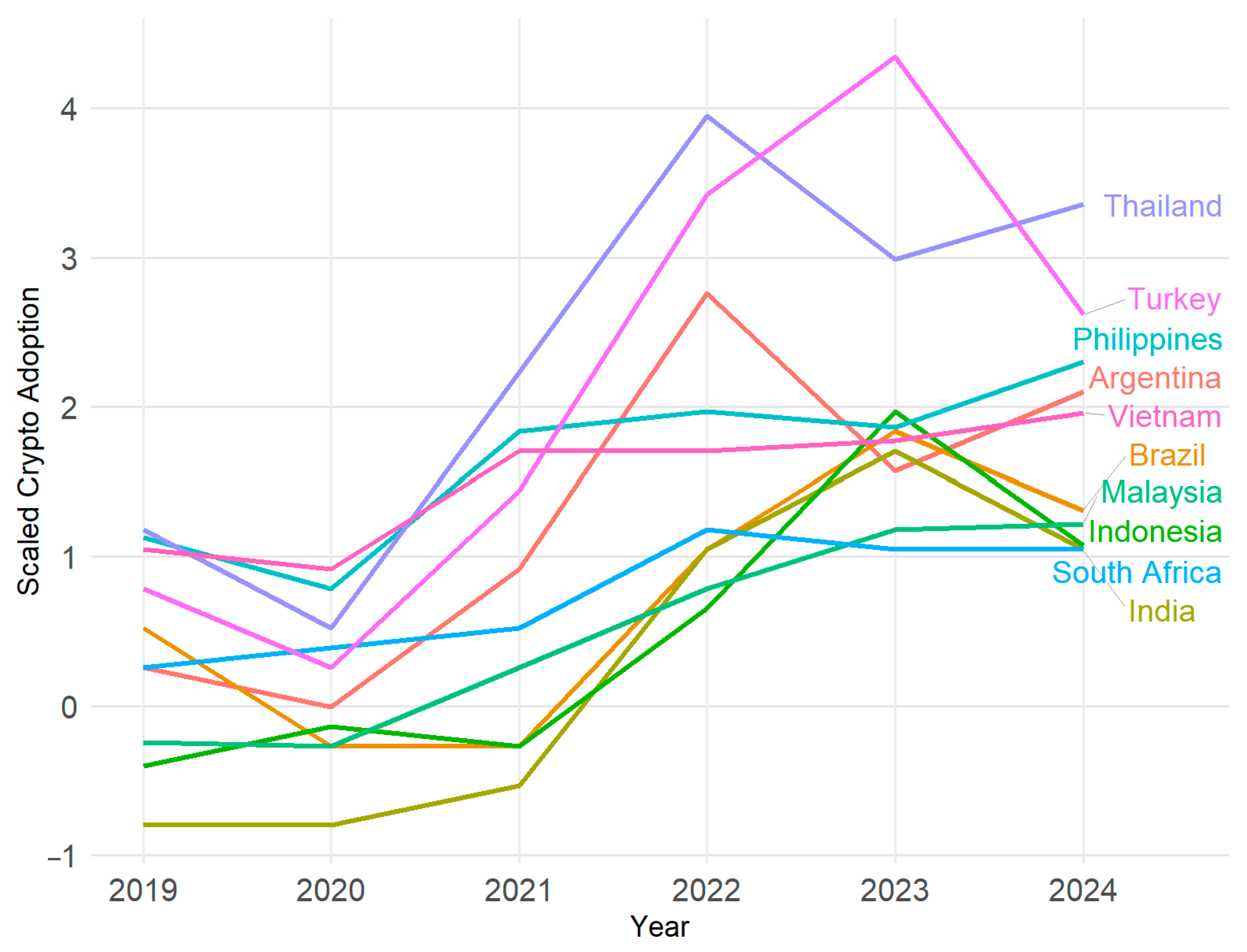

The inclusion of a diverse set of countries was intended to capture cryptocurrency adoption dynamics across a wide range of economic environments, thereby enhancing the study’s external validity. By incorporating developed and developing economies, the analysis facilitates cross-contextual comparisons that reflect varying degrees of technological readiness, financial infrastructure, and institutional trust. This heterogeneity allows for the identification of distinct adoption trajectories shaped by local conditions. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the dataset reveals pronounced contrasts; countries such as Turkey and Thailand exhibit rapid increases in adoption, while others, such as South Africa and Malaysia, display relatively stable or modest growth trends.

3.2. Independent Variables

This research utilises a variety of independent variables to represent various aspects of economic risk. Each variable is chosen based on its empirical validity, theoretical significance, and availability across different countries and time periods.

The CPI, published annually by Transparency International, serves as a widely recognised measure of perceived public sector corruption across countries, derived from expert assessments and business surveys (

Transparency International, 2025). As corruption is frequently employed as a proxy for institutional quality, this study uses the CPI to evaluate whether individuals in highly corrupt environments are more likely to disengage from traditional financial institutions and adopt decentralised alternatives such as cryptocurrency. This approach aligns with Hirschman’s EVL framework, wherein high perceived corruption may reduce the effectiveness of “voice” mechanisms, prompting strategic “exit” through alternative financial systems.

The inflation rate reflects the yearly percentage change in consumer prices and serves as an important indicator of the purchasing power of a currency. In situations where inflation undermines confidence in fiat currency, people may look to cryptocurrencies as alternative stores of value (

Birnbaum, 2025). From the perspective of the EVL framework, this behaviour represents a form of “exit”, a strategic withdrawal from malfunctioning monetary institutions when trust is eroded and avenues for reform are limited.

The unemployment rate serves as a proxy for labour market conditions and broader economic sentiment. While elevated unemployment is associated with economic hardship, recent scholarship indicates that favourable employment levels can support the diffusion of technological innovations by enhancing individuals’ financial stability and willingness to engage with emerging tools (

Bezirgan, 2023). This relationship aligns with IDT, which posits that adoption is more likely among those who are economically empowered and have access to digital infrastructure. Within this framework, unemployment functions as a critical differentiator; adoption in low-unemployment contexts may reflect innovation-seeking behaviour driven by opportunity, whereas in high-unemployment settings, adoption may be motivated by financial exclusion and necessity.

Exchange rate volatility reflects the degree to which a national currency fluctuates against major foreign currencies, posing risks to price stability, savings, and cross-border transactions. Elevated volatility can erode confidence in the domestic monetary regime, particularly in economies with limited monetary credibility, capital controls, or dual exchange rate systems. In such environments, individuals may increasingly turn to decentralised alternatives such as cryptocurrencies to preserve value and bypass formal exchange mechanisms. This behaviour aligns with the emerging “cryptoization” literature, which highlights the role of digital assets as substitutes in the face of fiat currency instability (

Sergio & Petti, 2024). Supporting this perspective,

Fernández-Villaverde and Sanches (

2016) argue that citizens are more likely to adopt private currencies when official money is volatile and prices fluctuate unpredictably.

Collectively, these indicators offer a multidimensional framework for assessing the conditions under which cryptocurrency adoption emerges. By incorporating measures of macroeconomic volatility and institutional fragility, the analysis captures both structural enablers and systemic pressures that may influence individuals to pursue decentralised financial alternatives. This integrated approach moves beyond reductionist explanations, allowing for a more nuanced examination of how economic risk and opportunity interact to shape global cryptocurrency adoption patterns.

3.3. Control Variables

To isolate the effects of economic risk on cryptocurrency adoption, the analysis incorporates three control variables that reflect a country’s digital and economic readiness. These variables capture the supply-side capacity necessary to support the uptake of digital financial technologies, ensuring that observed adoption patterns are not solely attributed to economic distress. By accounting for a nation’s underlying infrastructure and innovation capacity, the model distinguishes between adoption driven by systemic vulnerability and that facilitated by structural preparedness.

GDP per capita, sourced from the IMF, is included as a standard proxy for economic development. Higher levels of GDP per capita are generally associated with greater income levels, financial inclusion, and access to digital infrastructure, factors that collectively enhance a population’s capacity to experiment with and adopt emerging technologies (

Kanga et al., 2021). As such, economically advanced countries are more likely to exhibit the absorptive capacity required to integrate complex innovations like cryptocurrencies. To address skewness in the data and improve interpretability within the regression model, GDP per capita was log-transformed and subsequently standardised.

Internet penetration, sourced from the World Bank, captures the proportion of a country’s population with access to the internet and serves as a proxy for digital infrastructure. As engagement with cryptocurrencies necessitates reliable internet access, for activities such as managing digital wallets, interacting with exchanges, and verifying blockchain transactions, this variable constitutes a foundational condition for participation in decentralised finance. Consistent with IDT, internet penetration reflects a critical enabling factor that facilitates the uptake of emerging technologies by lowering access barriers and expanding digital inclusion across societies.

Regulatory permissiveness plays a pivotal role in shaping the institutional adoption of cryptocurrencies. Clear, supportive regulatory frameworks enhance investor confidence by reducing legal uncertainty and establishing safeguards for market participants. As more jurisdictions introduce comprehensive regulatory measures, institutional engagement with digital assets is expected to rise, thereby accelerating overall adoption (

Sadek et al., 2024). Conversely, restrictive policies or outright bans, such as those implemented in China, can act as significant deterrents, suppressing adoption by increasing perceived risk and discouraging participation in cryptocurrency markets.

To account for cross-national differences in the legal treatment of digital assets, a regulatory permissiveness index was constructed using data from the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance’s (CCAF) Cryptoasset Regulation Index. Countries were assigned an ordinal score based on the evolution of their regulatory environment; a score of “0” for outright bans on cryptoassets, “1” for jurisdictions lacking comprehensive regulation or operating under ambiguous legal conditions, and “2” for years in which a formal national regulatory framework for cryptoassets was adopted. This coding strategy captures temporal shifts in legal clarity and enforcement. For instance, Austria received a score of “1” from 2019 to 2022 and “2” in 2023 following the enactment of its comprehensive cryptoasset legislation (

CCAF, 2025). The scale is premised on the assumption that greater regulatory clarity reduces uncertainty and enhances trust, thereby creating more favourable conditions for cryptocurrency adoption.

According to the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance (CCAF), a “comprehensive regulatory framework” refers to a national policy regime that encompasses anti-money laundering (AML) and counter-terrorism financing (CTF) provisions, securities regulation, consumer protection measures, and licensing requirements for digital asset service providers (

CCAF, 2025). The regulation index used in this study draws on the comprehensiveness of these frameworks as a proxy for the degree of state involvement in the cryptocurrency economy. Unlike ad hoc or narrowly scoped regulations, a comprehensive framework signifies a deliberate effort by the state to govern the development and use of digital assets. This measure therefore captures when governments transition from reactive enforcement to proactive regulatory engagement, marking a key inflection point in the institutionalization of crypto adoption.

These control variables enable the differentiation between need-based adoption, where cryptocurrency uptake is motivated by economic instability, and opportunity-based adoption, which reflects structural readiness and innovation capacity. Their inclusion allows for a more granular analysis of the underlying drivers of cryptocurrency use when examined alongside risk-related predictors. All variables were standardised to normalise distributions and minimise skewness, thereby enhancing cross-country comparability and improving the robustness of the regression estimates.

3.4. Regression Model

To assess the relationship between risk indicators and cryptocurrency adoption, this study employs a panel regression model with country–year observations. The dependent variable, standardised cryptocurrency adoption, is analysed using a fixed-effects regression framework to account for unobserved, time-invariant heterogeneity across countries. The analysis was conducted using the “plm” package in R, with standard errors corrected using the Driscoll–Kraay method to ensure robustness to cross-sectional dependence, heteroskedasticity, and serial correlation.

The regression equation incorporates the CPI, exchange rate volatility, inflation rate, and unemployment rate. To account for structural readiness, control variables such as internet penetration, GDP per capita, and regulatory permissiveness are also included.

In this specification, represents unobserved, time-invariant, country-specific effects, while denotes the idiosyncratic error term. The fixed-effects framework allows for the empirical testing of the study’s four hypotheses by isolating the influence of economic risk factors, net of underlying structural development. The use of Driscoll–Kraay robust standard errors further enhances the reliability of coefficient estimates by addressing potential issues of autocorrelation, heteroskedasticity, and cross-sectional dependence among countries.

5. Discussion

The findings suggest a significant link between economic risk factors and the adoption of cryptocurrency, though the results do not always align with initial hypotheses. The analysis uncovers the following two distinct pathways for adoption: opportunity-driven adoption and constraint-driven adoption (as depicted on

Figure 5).

Opportunity-driven adoption (green arrow) is observed in environments characterised by favourable socioeconomic conditions, such as low unemployment, high GDP per capita, strong internet penetration, and the presence of comprehensive regulatory frameworks. These factors reflect a country’s structural readiness and absorptive capacity, key conditions that facilitate innovation uptake. In such contexts, cryptocurrency adoption emerges as a function of empowerment and proactive engagement with emerging technologies.

Constraint-driven adoption (orange arrow), by contrast, is more prevalent in countries experiencing elevated levels of economic instability, particularly where institutional trust is low, and corruption is widespread. Here, individuals are not drawn to cryptocurrency by opportunity but are instead pushed toward decentralised alternatives as a form of financial exit. This behaviour is consistent with the EVL model, wherein “exit” denotes withdrawal from failing institutional arrangements.

Importantly, the empirical findings reveal that opportunity-related structural factors, such as GDP per capita, internet penetration, and regulatory clarity, exert stronger and more consistent effects on cryptocurrency adoption. In contrast, most economic risk indicators, particularly inflation and exchange rate volatility, do not demonstrate significant associations. This does not undermine the dual-path framework; instead, it suggests that structural readiness is a necessary precondition for widespread adoption, even in constraint-driven contexts. Notably, institutional risk factors such as corruption and unemployment remain statistically significant, supporting the idea that constraint-driven adoption emerges only when sufficient structural infrastructure is in place. Thus, the results suggest an interaction effect; institutional dissatisfaction may prompt adoption, but only when enabling conditions (such as internet access) make such a shift feasible.

Ultimately, both pathways converge on the same behavioural outcome, cryptocurrency adoption, but differ in their underlying drivers and theoretical grounding. This dual-path model enhances our understanding of adoption dynamics by illustrating that innovation may be catalysed either by the presence of opportunity or the pressure of constraint, each operating through distinct but interrelated mechanisms.

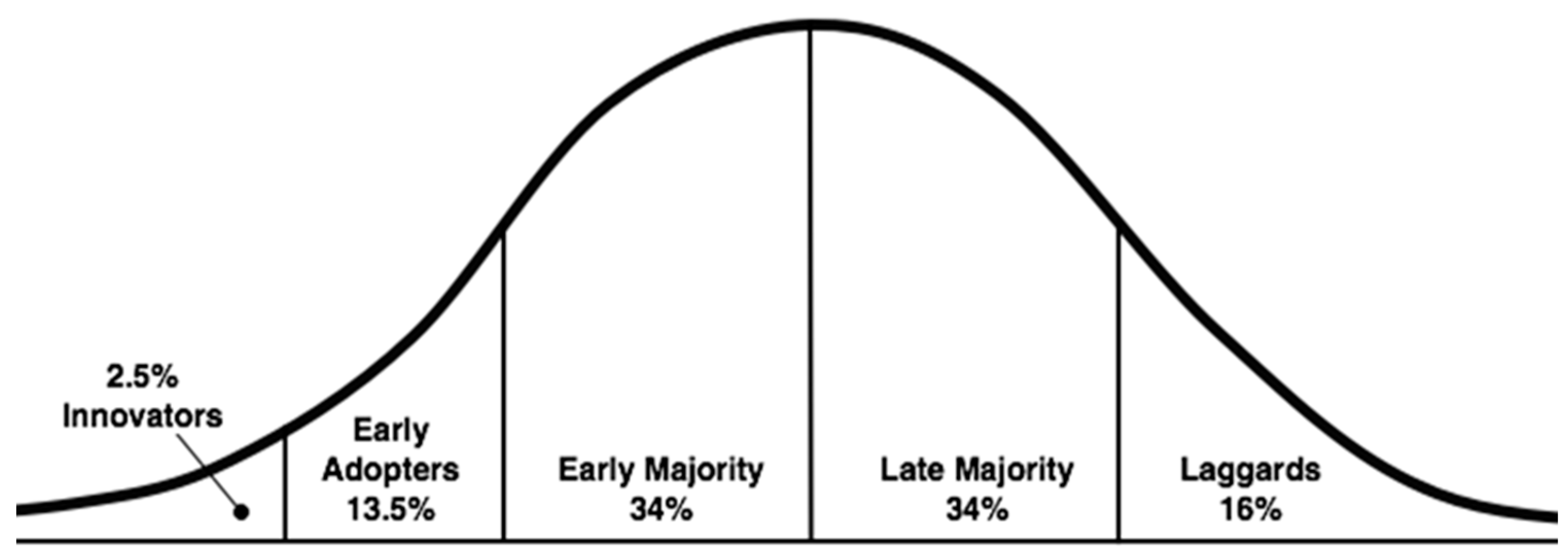

While at first glance it may appear contradictory that elevated corruption and low unemployment are associated with increased cryptocurrency adoption (given that one is a marker of dysfunction and the other of prosperity), this finding aligns with the logic of the dual-path model. These two predictors operate through distinct but parallel mechanisms. In high-corruption environments, adoption reflects constraint-driven behaviour, where individuals disengage from dysfunctional institutions in search of more trustworthy, decentralised alternatives, consistent with Hirschman’s “exit” logic. In contrast, in low-unemployment contexts, adoption reflects opportunity-driven motives; individuals are economically empowered, digitally connected, and more likely to experiment with innovative financial tools. This pattern is consistent with Rogers’ IDT, which suggests that early adopters are often found in structurally advantaged settings. Therefore, these findings demonstrate that cryptocurrency adoption can emerge as a response to institutional failure or as a reflection of prosperity and technological readiness, depending on the surrounding socioeconomic context.

The results from this study suggest that clear and supportive regulations encourage adoption. At first glance, this could appear contradictory; people turn to crypto to escape broken systems, yet strong regulations help it grow. However, this reflects two distinct stages in the adoption curve. In contexts of institutional failure, individuals may adopt crypto as a form of “exit.” However, for broader, mainstream diffusion to occur, beyond early adopters, there must be trust in new forms of governance and rules. This is consistent with IDT, which posits that later adopters require security and legitimacy. In this way, regulatory clarity does not oppose institutional distrust but instead enables distrust-led adoption to evolve into mainstream integration.

The dual-path model suggests the presence of deeper mediating and moderating mechanisms. Specifically, for constraint-driven adoption, perceived corruption may lead to lower institutional trust, which in turn motivates individuals to seek decentralised financial tools, suggesting that institutional trust could act as a mediator. Similarly, economic instability may only translate into adoption where enabling conditions (such as internet penetration or mobile banking infrastructure) exist, making these factors moderators of the relationship. In opportunity-driven contexts, the relationship between low unemployment and adoption may be mediated by increased financial literacy or exposure to fintech platforms. Consequently, future research should formally test these mechanisms, as their inclusion could sharpen the explanatory power of the dual-path model and reveal critical inflexion points for policy intervention.

These findings offer several broader theoretical implications. Specifically, this study contributes to and complicates the growing literature that portrays cryptocurrencies as “hedges” against systemic risk (

Yilmazkuday, 2024;

Birnbaum, 2025). While prior research has focused on price volatility and the safe-haven function of cryptocurrencies during crises, this paper shifts the focus to behavioural adoption at the population level, demonstrating that uptake is influenced by systemic factors beyond price dynamics. Moreover, by empirically validating the dual-path model, the findings also bridge a gap between financial inclusion literature (for example,

Bhimani et al., 2022) and institutional exit theories (

Alnasaa et al., 2022), demonstrating that cryptocurrency can function both as a tool for empowerment and as a vehicle for protest or disengagement. These insights call for a rethinking of crypto not only as a financial asset class but also as a sociotechnical response to systemic pressures and structural opportunities.

5.1. Policy Implications

These findings carry important implications for policymakers seeking to regulate and guide the growth of cryptocurrency markets. By identifying the structural and institutional conditions that facilitate adoption, this research enables more targeted and proactive regulatory interventions. Specifically, countries characterised by high levels of corruption and greater structural capacity, such as widespread internet access and elevated GDP per capita, should prioritise the development of comprehensive legal frameworks for digital assets. For example, Turkey and Argentina illustrate a scenario where, despite low levels of institutional trust, favourable digital and economic conditions have led to a swift increase in cryptocurrency adoption. Developing regulation can enhance market transparency, promote user trust, and support the integration of cryptocurrencies into the financial system. In turn, this approach mitigates systemic risks and reduces the likelihood of negative externalities associated with unregulated or rapid adoption, such as speculative bubbles or financial instability.

5.2. Limitations

Several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the dataset comprises 41 countries selected based on data availability, which (while diverse) may exclude certain high-risk or low-connectivity states where alternative drivers of cryptocurrency adoption prevail. Second, although multiple imputation and PCA were employed to address missing data and multicollinearity, these techniques rest on assumptions that may not fully hold across heterogeneous country contexts. For instance, PMM assumes that data are missing at random, and while this method is appropriate for modelling adoption patterns, the presence of unobserved confounders may still introduce bias. Despite these limitations, this study contributes to the literature by offering one of the first globally comparative, theory-grounded, and empirically robust examinations of the relationship between economic risk and cryptocurrency adoption. Notably, it introduces a novel country-level index of regulatory permissiveness as a control variable, enabling a more refined assessment of how legal frameworks influence adoption behaviour. By moving beyond binary classifications of cryptocurrency as either speculative or apolitical, this research provides a more nuanced perspective; one in which institutional fragility and structural capacity interact to shape patterns of adoption. Future research should extend this framework by incorporating direct measures of institutional trust and user-level psychological variables to further elucidate the mechanisms driving adoption.