Socially Responsible Investing: Is Social Media an Influencer?

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature

1.1.1. Social Media

1.1.2. Social Media as a Financial Information Source

1.1.3. Social Media and Socially Responsible Investing

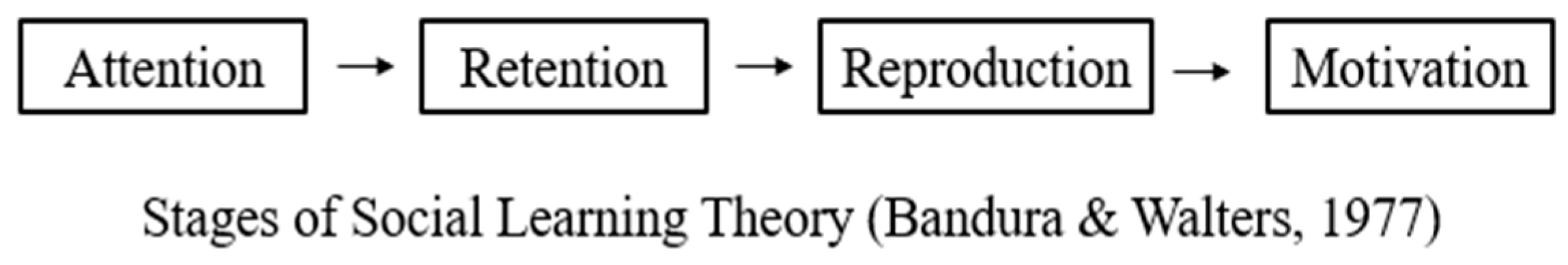

1.2. Theory

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Dependent Variable

2.2. Independent Variables

2.3. Control Variables

3. Results

3.1. SRI in the Age of Digital Information

3.2. Social Media Platforms and SRI

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Altaf, H., & Jan, A. (2023). Generational theory of behavioral biases in investment behavior. Borsa Istanbul Review, 23(4), 834–844. [Google Scholar]

- Aristei, D., & Gallo, M. (2023). Gender-related effects of financial knowledge and confidence on preferences for ethical intermediaries and sustainable investments. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 42(3), 486–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arora, M. K., Singh, J., & Singh, A. (2024). Development of intelligent system based on synthesis of affective signals and deep neural networks to foster mental health of the Indian virtual community. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 14, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aulia, M., Afiff, A. Z., Hati, S. R. H., & Gayatri, G. (2024). Consumers’ sustainable investing: A systematic literature review and research agenda. Cleaner and Responsible Consumption, 14, 100215. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, H. K., & Nofsinger, J. R. (2012). Socially responsible finance and investing: Financial institutions, corporations, investors, and activists. John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action (pp. 23–28). Prentice-Hall, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Jeffrey, R. W. (1973). Role of symbolic coding and rehearsal processes in observational learning. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 26(1), 122–130. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A., & Walters, R. H. (1977). Social learning theory (Vol. 1, pp. 141–154). Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, R., & Smeets, P. (2015). Social identification and investment decisions. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 117, 121–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, A., & O’Shea, A. (2024, August 20). What is socially responsible investing (SRI) and how to get started. NerdWallet. Available online: https://www.nerdwallet.com/article/investing/socially-responsible-investing (accessed on 17 May 2025).

- Bikhchandani, S., & Sharma, S. (2001). Herd behavior in financial markets. IMF Staff Papers, 47(3), 279–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bishara, A. J., & Hittner, J. B. (2012). Testing the significance of a correlation with nonnormal data: Comparison of Pearson, Spearman, transformation, and resampling approaches. Psychological Methods, 17(3), 399. [Google Scholar]

- Camilleri, M. A. (2021). The market for SRI: A review of the developments. Social Responsibility Journal, 17(3), 412–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, S., & Chang, Y. (2025). Utilization of alternative financial services and the role of financial capability. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 59(1), e12614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H., & Hwang, B. H. (2022). Listening in on investors’ thoughts and conversations. Journal of Financial Economics, 143(1), 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. X. (2019). Confirmation bias in investments. International Journal of Economics and Finance, 11(2), 50–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deaton, S. (2015). Social learning theory in the age of social media: Implications for educational practitioners. Journal of Educational Technology, 12(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- FINRA Investor Education Foundation (FINRA). (2022). Highlights from the FINRA foundation national financial capability study. Available online: https://www.finrafoundation.org/sites/finrafoundation/files/NFCS-Report-Fifth-Edition-July-2022.pdf (accessed on 23 June 2025).

- Firmansyah, D., & Saepuloh, D. (2022). Social learning theory: Cognitive and behavioral approaches. Jurnal Ilmiah Pendidikan Holistik (JIPH), 1(3), 297–324. [Google Scholar]

- Fryling, M. J., Johnston, C., & Hayes, L. J. (2011). Understanding observational learning: An interbehavioral approach. The Analysis of Verbal Behavior, 27, 191–203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Green, D., & Roth, B. (2024). The allocation of socially responsible capital. Journal of Finance, 80(2), 755–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horsburgh, J., & Ippolito, K. (2018). A skill to be worked at: Using social learning theory to explore the process of learning from role models in clinical settings. BMC Medical Education, 18, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, H., & Nam, S. J. (2021). Social media use and subjective well-being among middle-aged consumers in Korea: Mediation model of social capital moderated by disability. Journal of Consumer Affairs, 55(3), 832–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, R., Gupta, S., & Tiwari, A. K. (2025). Environmental, social and governance-type investing: A multi-stakeholder machine learning analysis. Management Decision. Advance online publication. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joseph, M., Lim, H. N., Lawson, D., MacDonald, M., & Chua, A. (2024). Do ostriches worry less? Information avoidance and retirement worry. Journal of Financial Therapy, 15(2), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Junkus, J. C., & Berry, T. C. (2010). The demographic profile of socially responsible investors. Managerial Finance, 36(6), 474–481. [Google Scholar]

- Khemir, S., Baccouche, C., & Ayadi, S. D. (2019). The influence of ESG information on investment allocation decisions: An experimental study in an emerging country. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 20(4), 489–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K. T., & Fan, L. (2025). Beyond the hashtags: Social media usage and cryptocurrency investment. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(3), 569–590. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, S., & Zhang, Y. (2020). The role of the media in socially responsible investing. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 38(4), 823–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. T., Bumcrot, C., Mottola, G., Valdes, O., & Walsh, G. (2022). The changing landscape of investors in the United States: A report of the national financial capability study. FINRA Investor Education Foundation. Available online: www.FINRAFoundation.org/Investor-Report2021 (accessed on 27 June 2025).

- Meng, X., Zhang, W., Li, Y., Cao, X., & Fen, X. (2020). Social media effect, investor recognition and the cross-section of stock returns. International Review of Financial Analysis, 67, 101432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolas, M. L. D., Desroziers, A., Caccioli, F., & Aste, T. (2024). ESG reputation risk matters: An event study based on social media data. Finance Research Letters, 59, 104712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquino, M., & Lucarelli, C. (2025). Socially responsible investments inside out: A new conceptual framework for investigating retail investor preferences. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 43(3), 449–475. [Google Scholar]

- Rooh, S., El-Gohary, H., Khan, I., Alam, S., & Shah, S. M. A. (2023). An attempt to understand stock market investors’ behaviour: The case of environmental, social, and governance (ESG) forces in the Pakistani stock market. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(12), 500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, M., Sansone, D., Van Soest, A., & Torricelli, C. (2019). Household preferences for socially responsible investments. Journal of Banking & Finance, 105, 107–120. [Google Scholar]

- Safdie, S. (2024, August 28). Socially responsible investing (SRI): All you need to know. Greenly. Available online: https://greenly.earth/en-us/blog/industries/socially-responsible-investing-sri-all-you-need-to-know (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Sandberg, J., Juravle, C., Hedesström, T. M., & Hamilton, I. (2009). The heterogeneity of socially responsible investment. Journal of Business Ethics, 87(4), 519–533. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40294943 (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Schueth, S. (2003). Socially responsible investing in the United States. Journal of Business Ethics, 43(3), 189–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schunk, D. H., & DiBenedetto, M. K. (2020). Motivation and social cognitive theory. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 60, 101832. [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan, R., & Mackenzie, C. (Eds.). (2017). Responsible investment (1st ed.). Routledge. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talan, G., Sharma, G. D., Pereira, V., & Muschert, G. W. (2024). From ESG to holistic value addition: Rethinking sustainable investment from the lens of stakeholder theory. International Review of Economics & Finance, 96(Pt A), 103530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, C. G., Kim, R. S., Aloe, A. M., & Becker, B. J. (2017). Extracting the variance inflation factor and other multicollinearity diagnostics from typical regression results. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 39(2), 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- US SIF. (2024, December 18). The forum for sustainable and responsible investment. In US sustainable investing trends 2024/2025—Executive summary. Available online: https://www.ussif.org/research/trends-reports/us-sustainable-investing-trends-2024-2025-executive-summary (accessed on 16 May 2025).

- Viviers, S., & Eccles, N. S. (2012). 35 years of socially responsible investing (SRI) research: General trends over time. South African Journal of Business Management, 43(4), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Weighted n | % | n | % | |

| Investment Experience | ||||

| Less than 1 year | 92.88 | 4.46 | 86 | 4.13 |

| 1 year to less than 2 years | 179.11 | 8.60 | 159 | 7.63 |

| 2 years to less than 5 years | 188.99 | 9.07 | 190 | 9.12 |

| 5 years to less than 10 years | 232.90 | 11.18 | 222 | 10.66 |

| 10 years or more | 1389.12 | 66.69 | 1426 | 68.46 |

| Investment Assets | ||||

| Less than USD 50 K | 620.81 | 29.80 | 602 | 28.90 |

| USD 50 K up to USD 100 K | 257.50 | 12.36 | 265 | 12.72 |

| USD 100 K up to USD 500 K | 703.10 | 33.75 | 685 | 32.89 |

| USD 500 K up to USD 1 M | 239.76 | 11.51 | 256 | 12.29 |

| USD 1 M or more | 261.84 | 12.57 | 275 | 13.20 |

| Investment Risk Preference | ||||

| Take substantial financial risk | 181.29 | 8.70 | 174 | 8.34 |

| Take above average financial risk | 563.86 | 27.07 | 595 | 28.51 |

| Take average financial risk | 1152.48 | 55.33 | 1142 | 54.72 |

| Not willing to take any financial risk | 185.37 | 8.90 | 176 | 8.43 |

| Income | ||||

| Less than USD 50 K | 436.17 | 20.94 | 424 | 20.36 |

| USD 50 K up to USD 100 K | 807.23 | 38.75 | 805 | 38.65 |

| USD 100 K or more | 839.60 | 40.31 | 854 | 41.00 |

| Age | ||||

| 18 to 24 | 68.94 | 3.31 | 57 | 2.74 |

| 25 to 34 | 152.17 | 7.31 | 152 | 7.30 |

| 35 to 44 | 278.54 | 13.37 | 268 | 12.87 |

| 45 to 54 | 248.10 | 11.91 | 268 | 12.87 |

| 55 to 64 | 475.78 | 22.84 | 470 | 22.56 |

| 65 and older | 859.47 | 41.26 | 868 | 41.67 |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1328.83 | 63.79 | 1322 | 63.47 |

| Female | 754.17 | 36.21 | 761 | 36.53 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| White, non-Hispanic | 1556.78 | 74.74 | 1717 | 82.43 |

| Non-White | 526.22 | 25.26 | 366 | 17.57 |

| Education | ||||

| HS or less | 200 | 9.60 | 242 | 11.63 |

| Some college | 373 | 17.91 | 409 | 19.66 |

| Associate’s | 212 | 10.18 | 241 | 11.58 |

| Bachelor’s | 816 | 39.17 | 744 | 35.71 |

| Post-graduate | 482 | 23.14 | 446 | 21.43 |

| Employment Status | ||||

| Self-employed | 171.57 | 8.24 | 175 | 8.40 |

| Full-time | 773.16 | 37.12 | 792 | 38.02 |

| Part-time | 128.57 | 6.17 | 132 | 6.34 |

| Retired | 858.13 | 41.20 | 851 | 40.85 |

| Other | 151.57 | 7.28 | 133 | 6.39 |

| Marital Status | ||||

| Married | 1392.61 | 66.86 | 1389 | 66.68 |

| Single | 380.44 | 18.26 | 374 | 17.95 |

| Separated/Divorced/Widowed | 309.95 | 14.88 | 320 | 15.36 |

| n | Mean | Std Dev | Min/Max | |

| Subjective financial knowledge | 2083 | 4.80 | 1.34 | 1/7 |

| Objective financial knowledge | 2083 | 4.37 | 1.41 | 0/6 |

| Weighted n | % | n | % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social Media Platforms Used for Investing Information | ||||

| YouTube | 417.68 | 20.05 | 408 | 18.83 |

| 221.06 | 10.61 | 225 | 10.41 | |

| 219.69 | 10.55 | 220 | 10.24 | |

| 211.28 | 10.14 | 205 | 9.59 | |

| Discord | 119.44 | 5.73 | 107 | 5.03 |

| Twitch | 66.65 | 3.20 | 64 | 3.01 |

| Clubhouse | 56.53 | 2.71 | 60 | 2.83 |

| 189.32 | 9.09 | 175 | 8.26 | |

| 176.54 | 8.48 | 162 | 7.57 | |

| Stocktwits | 117.47 | 5.64 | 108 | 5.11 |

| TikTok | 105.83 | 5.08 | 109 | 5.08 |

| Social Media Groups Used for Investment Decisions | ||||

| Not at all | 1652.48 | 79.33 | 1727 | 79.70 |

| Somewhat | 315.60 | 14.94 | 316 | 14.58 |

| A great deal | 114.92 | 5.52 | 124 | 5.72 |

| Variable | Measurement |

|---|---|

| Age | 18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, or 65 and older |

| Gender | Male or female |

| Race | White non-Hispanic or non-White |

| Marital status | Married, single, or separated/divorced/widowed |

| Education | HS or less, some college, associate’s, bachelor’s, or post-graduate |

| Employment status | Self-employed, full-time, part-time, retired, or other * |

| Objective financial knowledge | |

| Interest |

|

| Inflation |

|

| Bond pricing |

|

| Compounding |

|

| Mortgage |

|

| Portfolio risk |

|

| Subjective financial knowledge | ‘How would you assess your overall knowledge about investing?’ on a 7-point scale (1 = very low to, 7 = very high) |

| Investment assets | Less than USD 50 K, USD 50 K up to USD 100 K, USD 100 K up to USD 500 K, USD 500 K up to USD 1 M, or USD 1 M or more |

| Investment experience | Less than a year ago, 1 year to less than 2 years ago, 2 years to less than 5 years ago, 5 years to less than 10 years ago, or 10 years ago or more |

| Investment risk preference | Substantial financial risks, above average financial risks, average financial risks, or not willing to take any financial risks |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1.00 | ||||||||||

| 2 | 0.51 *** | 1.00 | |||||||||

| 3 | 0.43 *** | 0.34 *** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| 4 | 0.38 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.34 *** | 1.00 | |||||||

| 5 | 0.48 *** | 0.62 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.59 *** | 1.00 | ||||||

| 6 | 0.48 *** | 0.52 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.49 *** | 0.63 *** | 1.00 | |||||

| 7 | 0.39 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.40 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.45 *** | 1.00 | ||||

| 8 | 0.27 *** | 0.38 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.47 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.44 *** | 1.00 | |||

| 9 | 0.27 *** | 0.35 *** | 0.31 *** | 0.46 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.52 *** | 1.00 | ||

| 10 | 0.41 *** | 0.42 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.39 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.37 *** | 0.38 *** | 1.00 | |

| 11 | 0.25 *** | 0.30 *** | 0.33 *** | 0.26 *** | 0.29 *** | 0.32 *** | 0.34 *** | 0.43 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.34 *** | 1.00 |

| Socially Responsible Investing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β(SE) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social media | 0.91(0.15) *** | 2.49 | [1.87, 3.31] |

| Investment Exp (ref 10 yr or more) | |||

| Less than 1 yr | 0.31(0.29) | 1.36 | [0.77, 2.40] |

| 1 yr to less than 2 yr | 0.61(0.23) ** | 1.84 | [1.18, 2.87] |

| 2 yr to less than 5 yr | 0.52(0.20) ** | 1.68 | [1.14, 2.47] |

| 5 yr to less than 10 yr | 0.29(0.17) | 1.33 | [0.95, 1.88] |

| Investment Risk Preference (ref Average Risk) | |||

| Take substantial risk | 0.18(0.21) | 1.20 | [0.80, 1.79] |

| Take above average risk | 0.02(0.12) | 1.02 | [0.81, 1.29] |

| Not willing to take risk | −0.18(0.20) | 0.83 | [0.57, 1.22] |

| Age (ref 65 and older) | |||

| 18 to 24 | 0.68(0.41) | 1.96 | [0.88, 4.37] |

| 25 to 34 | 0.23(0.27) | 1.25 | [0.74, 2.13] |

| 35 to 44 | −0.11(0.22) | 0.90 | [0.59, 1.37] |

| 45 to 54 | −0.16(0.19) | 0.85 | [0.58, 1.24] |

| 55 to 64 | −0.03(0.15) | 0.97 | [0.72, 1.30] |

| Investment Assets (ref less than USD 50 K) | |||

| USD 50 K up to USD 100 K | 0.09(0.18) | 1.09 | [0.77, 1.54] |

| USD 100 K up to 500 K | 0.10(0.14) | 1.11 | [0.84, 1.47] |

| USD 500 K up to USD 1 M | 0.09(0.19) | 1.09 | [0.75, 1.58] |

| USD 1 M or more | 0.13(0.20) | 1.14 | [0.77, 1.67] |

| Subj financial knowledge | 0.30(0.04) *** | 1.35 | [1.24, 1.48] |

| Obj financial knowledge | −0.21(0.04) *** | 0.81 | [0.75, 0.88] |

| Gender (ref Male) | |||

| Female | 0.46(0.11) *** | 1.59 | [1.27, 1.98] |

| Own Home (ref Yes) | |||

| No | −0.37(0.16) * | 0.69 | [0.51, 0.95] |

| Ethnicity (ref White non-Hispanic) | |||

| Non-White | 0.41(0.13) ** | 1.51 | [1.17, 1.96] |

| Income | 0.00(0.08) | 1.00 | [0.85, 1.18] |

| Marital Status (ref Married) | |||

| Single | 0.14(0.16) | 1.15 | [0.85, 1.54] |

| Separated/Divorced | 0.27(0.15) | 1.31 | [0.98, 1.76] |

| Education (ref Bachelor’s) | |||

| HS or less | −0.33(0.19) | 0.72 | [0.49, 1.04] |

| Some college | −0.27(0.15) | 0.76 | [0.57, 1.02] |

| Associate’s | −0.28(0.18) | 0.76 | [0.53, 1.08] |

| Post-graduate | 0.21(0.13) | 1.23 | [0.95, 1.58] |

| Employment (ref Full-time) | |||

| Self-employed | 0.02(0.19) | 1.02 | [0.71, 1.48] |

| Part-time | 0.20(0.22) | 1.22 | [0.80, 1.85] |

| Retired | −0.46(0.16) ** | 0.63 | [0.46, 0.86] |

| Other + | −0.25(0.23) | 0.78 | [0.50, 1.21] |

| N | 2083 | ||

| Log pseudo-likelihood | −1211.626 | ||

| Chi-square | 370.32 *** | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.133 | ||

| Socially Responsible Investing | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| β(SE) | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social Media Platforms Used for Financial Information | |||

| YouTube | −0.38(0.17) * | 0.68 | [0.49, 0.94] |

| −0.36(0.24) | 0.70 | [0.44, 1.11] | |

| −0.23(0.21) | 0.80 | [0.52, 1.21] | |

| TikTok | −0.11(0.38) | 0.90 | [0.43, 1.87] |

| −0.63(0.34) | 0.53 | [0.27, 1.03] | |

| −0.53(0.25) * | 0.59 | [0.36, 0.97] | |

| Discord | 0.12(0.32) | 1.12 | [0.60, 2.12] |

| Twitch | −0.12(0.50) | 0.89 | [0.33, 2.39] |

| Clubhouse | 0.24(0.52) | 1.27 | [0.46, 3.50] |

| −0.55(0.23) * | 0.58 | [0.37, 0.91] | |

| Stocktwits | −0.21(0.29) | 0.81 | [0.46, 1.43] |

| Investment Exp (ref 10 yr or more) | |||

| Less than 1 yr | 0.29(0.29) | 1.34 | [0.76, 2.39] |

| 1 yr to less than 2 yr | 0.51(0.23) * | 1.67 | [1.06, 2.63] |

| 2 yr to less than 5 yr | 0.44(0.20) * | 1.55 | [1.05, 2.31] |

| 5 yr to less than 10 yr | 0.21(0.18) | 1.24 | [0.87, 1.76] |

| Investment Risk Preference (ref Average Risk) | |||

| Take substantial risk | −0.01(0.22) | 0.99 | [0.64, 1.53] |

| Take above average risk | 0.01(0.12) | 1.00 | [0.80, 1.27] |

| Not willing to take risk | −0.21(0.20) | 0.81 | [0.55, 1.19] |

| Age (ref 65 and older) | |||

| 18 to 24 | 0.40(0.43) | 1.50 | [0.64, 3.51] |

| 25 to 34 | 0.09(0.28) | 1.10 | [0.64, 1.89] |

| 35 to 44 | −0.13(0.22) | 0.88 | [0.57, 1.35] |

| 45 to 54 | −0.20(0.20) | 0.81 | [0.56, 1.20] |

| 55 to 64 | −0.02(0.15) | 0.98 | [0.73, 1.31] |

| Investment Assets (ref less than USD 50 K) | |||

| USD 50 K up to USD 100 K | 0.07(0.18) | 1.07 | [0.75, 1.52] |

| USD 100 K up to 500 K | 0.05(0.15) | 1.05 | [0.79, 1.41] |

| USD 500 K up to USD 1 M | 0.05(0.19) | 1.05 | [0.72, 1.54] |

| USD 1 M or more | 0.12(0.20) | 1.13 | [0.77, 1.66] |

| Subj financial knowledge | 0.26(0.05) *** | 1.30 | [1.19, 1.42] |

| Obj financial knowledge | −0.18(0.04) *** | 0.83 | [0.77, 0.91] |

| Gender (ref Male) | |||

| Female | 0.52(0.11) *** | 1.68 | [1.34, 2.09] |

| Own Home (ref Yes) | |||

| No | −0.35(0.16) * | 0.70 | [0.51, 0.97] |

| Ethnicity (ref White non-Hispanic) | |||

| Non-White | 0.41(0.13) ** | 1.51 | [1.16, 1.96] |

| Income | −0.01(0.08) | 0.99 | [0.84, 1.17] |

| Marital Status (ref Married) | |||

| Single | 0.19(0.15) | 1.20 | [0.89, 1.63] |

| Separated/Divorced | 0.25(0.15) | 1.29 | [0.96, 1.72] |

| Education (ref Bachelor’s) | |||

| HS or less | −0.31(0.19) | 0.74 | [0.50, 1.08] |

| Some college | −0.24(0.15) | 0.79 | [0.59, 1.06] |

| Associate’s | −0.24(0.18) | 0.79 | [0.55, 1.12] |

| Post-graduate | 0.19(0.13) | 1.21 | [0.93, 1.56] |

| Employment (ref Retired) | |||

| Self-employed | 0.02(0.19) | 1.02 | [0.70, 1.49] |

| Part-time | 0.21(0.22) | 1.23 | [0.80, 1.88] |

| Retired | −0.45(0.16) * | 0.64 | [0.47, 0.88] |

| Other + | −0.23(0.23) | 0.79 | [0.51, 1.24] |

| N | 2083 | ||

| Log pseudo-likelihood | −1195.078 | ||

| Wald Chi-square | 403.42 *** | ||

| Pseudo R2 | 0.144 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Joseph, M.; Ouyang, C.; DeVille, J. Socially Responsible Investing: Is Social Media an Influencer? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070382

Joseph M, Ouyang C, DeVille J. Socially Responsible Investing: Is Social Media an Influencer? Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(7):382. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070382

Chicago/Turabian StyleJoseph, Mindy, Congrong Ouyang, and Joanne DeVille. 2025. "Socially Responsible Investing: Is Social Media an Influencer?" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 7: 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070382

APA StyleJoseph, M., Ouyang, C., & DeVille, J. (2025). Socially Responsible Investing: Is Social Media an Influencer? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(7), 382. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18070382