Does Sustainability Orientation Drive Financial Success in a Non-Ergodic World? A Systematic Literature Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: How is SO defined and conceptualised in the existing academic literature?

- RQ2: How can the relationship between a firm’s SO and FP be characterised?

- RQ3: What are the major themes emerging from recent research on SO and FP?

- RQ4: What knowledge gaps do the major themes reveal for future research?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Approach to Systematic Literature Review

2.2. Approach to Thematic Analysis

- converting all text to lowercase;

- removing special characters (e.g., /, ‘, “);

- manually removing section labels in abstracts (e.g., “purpose”, “methodology”, “results”);

- removing any copyright statements;

- removing all numerical characters;

- removing common stop words with no lexical meaning.

3. Defining Sustainability Orientation

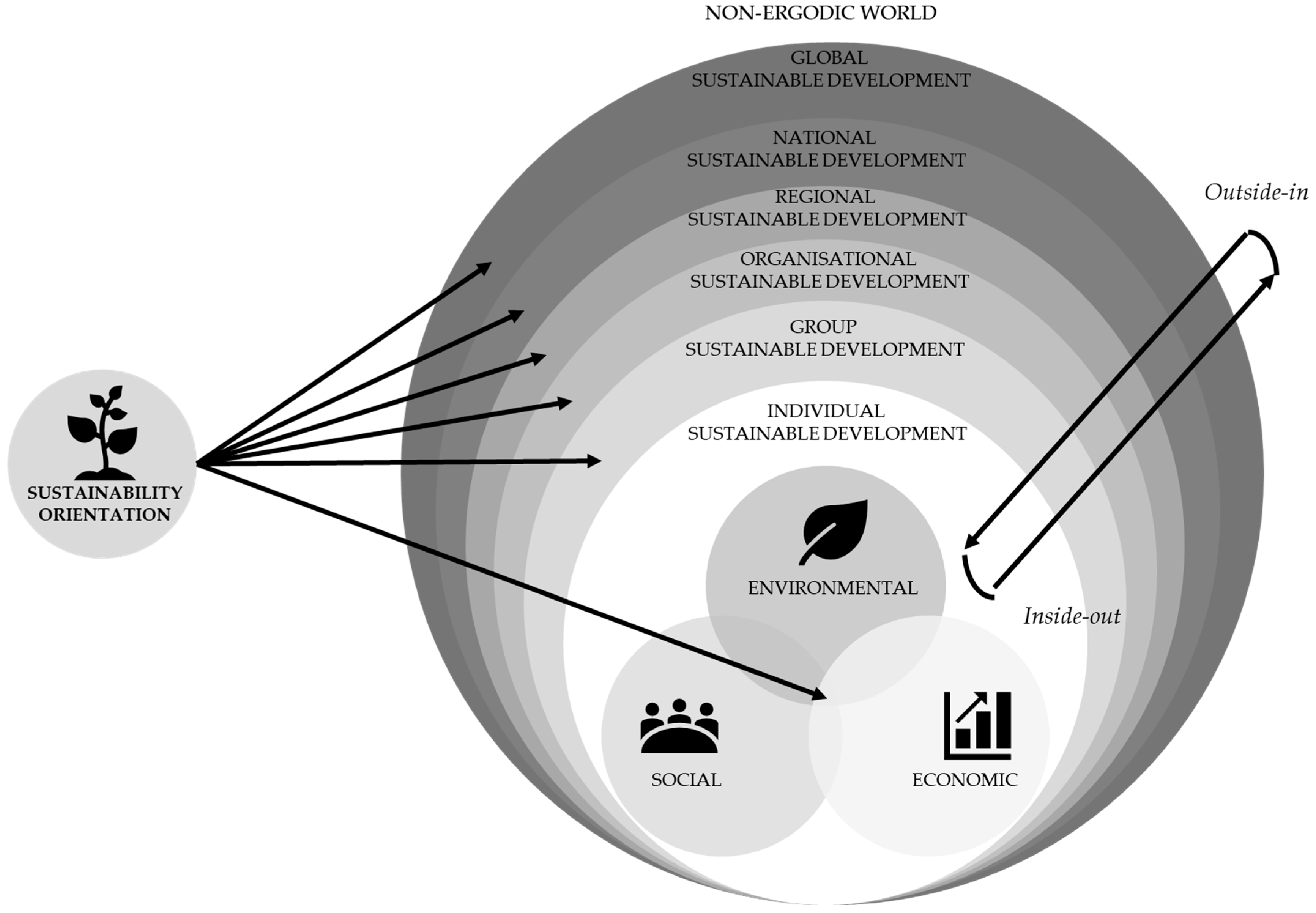

4. Theoretical Framework

4.1. Resource-Based Theory

4.2. Institutional Theory

4.3. Stakeholder Theory

4.4. Combination of the Theoretical Framework

SO is a proactive and holistic strategic stance that integrates environmental, social and economic considerations into values, resources, decision making and operations to create long-term value and achieve SD at individual, group, organisational, regional, national and global levels. It reflects an internal capability—developing unique resources and competencies for SD—while responding to external opportunities and threats and aligning with surrounding stakeholder interests.

5. Sustainability Orientation and Financial Performance

5.1. Sustainability Orientation and Financial Performance: Overall Relationship

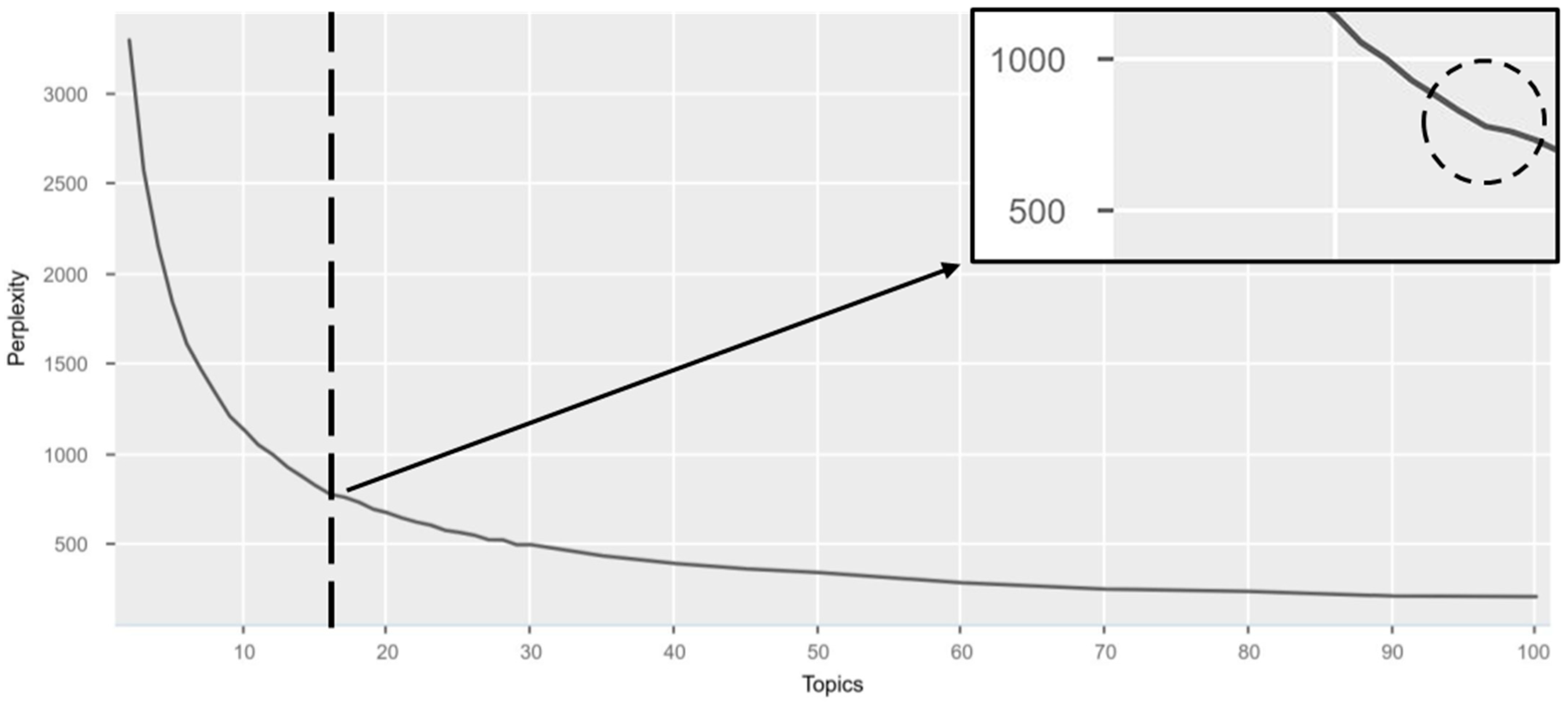

5.2. Topic Modelling

5.3. Thematic Analysis

6. Discussion

7. Conclusions, Limitations, Implications and Future Research Areas

7.1. Conclusions

7.2. Limitations

7.3. Implications

7.4. Future Research Areas

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SD | Sustainable development |

| SO | Sustainability orientation |

| FP | Financial performance |

| SLR | Systematic literature review |

| LDA | Topic modelling using latent Dirichlet allocation |

| RBT | Resource-Based Theory |

| IT | Institutional Theory |

| ST | Stakeholder Theory |

| PRISMA | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses |

| ESG | Environmental, social and governance |

| SME | Small and medium enterprises |

| CSR | Corporate social responsibility |

Appendix A

| Stage | Query Code | Result | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Web of Science | Scopus | Web of Science | Scopus | |

| Stage 1 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*))) | 1266 | 864 |

| Stage 2 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025) | 1244 | 838 |

| Stage 3 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) and Management or Business or Economics or Business Finance (Web of Science Categories) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“ECON”))) | 790 | 482 |

| Stage 4 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) and Management or Business or Economics or Business Finance (Web of Science Categories) and Article (Document Types) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“ECON”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”))) | 704 | 399 |

| Stage 5 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) and Management or Business or Economics or Business Finance (Web of Science Categories) and Article (Document Types) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2005 (Final Publication Year) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“ECON”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,“final”))) | 655 | 379 |

| Stage 6 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) and Management or Business or Economics or Business Finance (Web of Science Categories) and Article (Document Types) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2005 (Final Publication Year) and English (Languages) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“ECON”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,“final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,“English”))) | 640 | 367 |

| Stage 7 | sustainab* (Topic) and orient* (Topic) and financ* (Topic) and perform* (Topic) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2006 or 2005 (Publication Years) and Management or Business or Economics or Business Finance (Web of Science Categories) and Article (Document Types) and 2024 or 2023 or 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 or 2012 or 2011 or 2010 or 2009 or 2008 or 2007 or 2005 (Final Publication Year) and English (Languages) and All Open Access (Open Access) | ((TITLE-ABS-KEY(sustainab*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(orient*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(financ*) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY(perform*)) AND PUBYEAR > 1991 AND PUBYEAR < 2025 AND (LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“BUSI”) OR LIMIT-TO (SUBJAREA,“ECON”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (DOCTYPE,“ar”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (PUBSTAGE,“final”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (LANGUAGE,“English”)) AND (LIMIT-TO (OA,“all”))) | 238 | 149 |

| Stage 8 | Elimination of duplicate values from the results of both databases in Bibliometrix. | 296 | ||

| Stage 9 | Manual title and abstract screening. | 190 | ||

| Stage 10 | Manual retrieval of articles. | 186 | ||

| Stage 11 | Manual full-text review for further analysis, LDA topic modelling and thematic analysis. | 117 | ||

Appendix B

| No. | Topic | Top Terms | Coherence | Prevalence (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Topic 14 | Financial Performance | green, performance, innovation, orientation, entrepreneurial, manufacturing, product, financial, financial performance, entrepreneurial orientation, firms, study, product innovation, green product, manufacturing firms | 0.055 | 7.479 |

| Topic 8 | Gender Diversity | board, governance, ESG, family, study, firms, diversity, gender, sample, reporting, boards, directors, gender diversity, environmental, influence | 0.093 | 6.948 |

| Topic 9 | Sustainable Performance | performance, social, environmental, study, relationship, sustainable, geo, financial, medium, data, impact, sustainable performance, enterprises, medium-sized, sized | 0.042 | 6.59 |

| Topic 2 | Structural Equation | performance, practices, sustainability, SMEs (small and medium enterprises), study, structural equation, business, equation, structural, effects, corporate, role, financial, sustainable, mediating | 0.022 | 6.53 |

| Topic 7 | Corporate Social | CSR, corporate, corporate social, social responsibility, responsibility, social, responsibility CSR, countries, firms, role, performance, context, institutional, CSR performance, relationship | 0.509 | 6.49 |

| Topic 1 | Corporate Sustainability | sustainability, strategies, performance, market, corporate, study, findings, strategy, financial, firms, environmental, managerial, managers, negative, implications | 0.035 | 6.411 |

| Topic 17 | Financial Performance | green, firms, performance, capabilities, based, financial, financial performance, sustainability, relationship, leadership, pollution, role, resource, dynamic, chain | 0.034 | 6.321 |

| Topic 16 | Sustainability Orientation | environmental, sustainability, orientation, performance, sustainability orientation, organisational, findings, economic, environmental performance, strategic, social, firms, environmental sustainability orientation, resilience, companies | 0.044 | 6.184 |

| Topic 6 | Social Responsibility | social, innovation, responsibility, corporate, social responsibility, sustainability, oriented, sustainable, relationship, paper, firms, economic, corporate social, orientation, development | 0.202 | 5.851 |

| Topic 15 | Financial Performance | financial, firms, financial performance, performance, environmental, culture, internal, external, organisational, power, orientation, firm, market, resources, actions | 0.058 | 5.798 |

| Topic 4 | Stakeholder Engagement | engagement, stakeholder, quality, mechanisms, financial, stakeholders, sustainability, governance, firms, corporate, performance, stakeholder engagement, study, sustainable, financial performance | 0.191 | 5.431 |

| Topic 11 | Sustainability Orientation | performance, sustainable, orientation, micro and SME, sustainability, financial, study, circular economy, factors, sustainability orientation, impact, economy, SMEs, oriented innovation, business | 0.027 | 5.384 |

| Topic 3 | Business Performance | business, performance, management, environmental, environment, sustainable, development, financial, sustainable development, business performance, sustainable value added, sustainability, oriented, enterprises, corporate | 0.033 | 5.233 |

| Topic 12 | Bank Performance | CSR, bank, firms, study, corporate financial performance, performance, countries, companies, empirical, ownership, bank performance, practices, banks, economic, profitability | −0.046 | 5.139 |

| Topic 13 | Environmental Disclosure | disclosure, sustainability, companies, banks, senior, cultural, leaders, analysis, ESG, European, B-BBEE, EU, financial, reporting, mission | 0.066 | 4.956 |

| Topic 5 | Oriented Innovation | sustainability, executives, decision, financial, sustainable, oriented, finance, literature, models, regulation, data, reporting, risk, emerging, accounting | −0.015 | 4.796 |

| Topic 10 | Environmental Performance | environmental, performance, study, financial, sustainability, relationship, data, analysis, economic, organisations, conditions, governance, board, directors, management | 0.023 | 4.46 |

| 1 | General publications on Omnibus I. Available online: https://commission.europa.eu/publications/omnibus-i_en (accessed on 3 April 2025). |

| 2 | US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/01/putting-america-first-in-international-environmental-agreements (accessed on 5 April 2025). |

| 3 | US withdrawal from the UN Loss and Damage fund. Available online: https://www.lossanddamagecollaboration.org/resources/what-does-the-u-s-withdrawal-from-the-board-of-the-fund-for-responding-to-loss-and-damage-mean-for-loss-and-damage (accessed on 5 May 2025). |

| 4 | US reviewing membership in UNESCO. Available online: https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/02/withdrawing-the-united-states-from-and-ending-funding-to-certain-united-nations-organizations-and-reviewing-united-states-support-to-all-international-organizations (accessed on 5 May 2025). |

References

- Adomako, S., Amankwah-Amoah, J., Danso, A., Konadu, R., & Owusu-Agyei, S. (2019). Environmental sustainability orientation and performance of family and nonfamily firms. Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(6), 1250–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alaka, H. A., Oyedele, L. O., Owolabi, H. A., Kumar, V., Ajayi, S. O., Akinade, O. O., & Bilal, M. (2018). Systematic review of bankruptcy prediction models: Towards a framework for tool selection. Expert Systems with Applications, 94, 164–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, R. R. (2025). Outcomes of paradox responses in corporate sustainability: A qualitative meta-analysis. Business & Society, 64(5), 889–932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almada, L., Borges, R. S. G. e., & Ferreira, B. P. (2022). Are Natural-RBV strategies profitable? A longitudinal study of the Brazilian corporate sustainability index. Rbgn-Revista Brasileira de Gestao de Negocios, 24(3), 533–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ameer, R., & Othman, R. (2012). Sustainability practices and corporate financial performance: A study based on the top global corporations. Journal of Business Ethics, 108(1), 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, J. (2022). An attention-based view on environmental management: The influence of entrepreneurial orientation, environmental sustainability orientation, and competitive intensity on green product innovation in Swedish small manufacturing firms. Organization & Environment, 35(4), 627–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arco-Castro, M. L., López-Pérez, M. V., Alonso-Conde, A. B., & Rojo Suárez, J. (2024). Determinants of corporate environmental performance and the moderating effect of economic crises. Baltic Journal of Management, 19(6), 39–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aria, M., & Cuccurullo, C. (2017). Bibliometrix: An R-tool for comprehensive science mapping analysis. Journal of Informetrics, 11(4), 959–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahl, L. R., Jelinek, F., & Mercer, R. L. (1983). A maximum likelihood approach to continuous speech recognition. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, PAMI-5(2), 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. B., Ketchen, D. J., & Wright, M. (2021). Resource-based theory and the value creation framework. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1936–1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, D., & Chipulu, M. (2023). Developing a new scale for measuring sustainability-oriented innovation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 429, 139590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, G. G., & Dyck, B. (2011). Conventional resource-based theory and its radical alternative: A less materialist-individualist approach to strategy. Journal of Business Ethics, 99(Suppl. 1), 121–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bigelli, M., Mengoli, S., & Sandri, S. (2023). ESG score, board structure and the impact of the non-financial reporting directive on European firms. Journal of Economics and Business, 127, 106133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3(4–5), 601–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boso, N., Danso, A., Leonidou, C., Uddin, M., Adeola, O., & Hultman, M. (2017). Does financial resource slack drive sustainability expenditure in developing economy small and medium-sized enterprises? Journal of Business Research, 80, 247–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bundy, J., Vogel, R. M., & Zachary, M. A. (2018). Organization–stakeholder fit: A dynamic theory of cooperation, compromise, and conflict between an organization and its stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 39(2), 476–501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burdon, W. M., & Sorour, M. K. (2020). Institutional theory and evolution of ‘A Legitimate’ compliance culture: The case of the UK financial service sector. Journal of Business Ethics, 162(1), 47–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busch, T., Barnett, M. L., Burritt, R. L., Cashore, B. W., Freeman, R. E., Henriques, I., Husted, B. W., Panwar, R., Pinske, J., Schaltegger, S., & York, J. (2024). Moving beyond “the” business case: How to make corporate sustainability work. Business Strategy and the Environment, 33(2), 776–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabezas, H., Pawlowski, C. W., Mayer, A. L., & Hoagland, N. T. (2003). Sustainability: Ecological, social, economic, technological, and systems perspectives. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy, 5(3–4), 167–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmeli, A., Dothan, A., & Boojihawon, D. K. (2020). Resilience of sustainability-oriented and financially-driven organizations. Business Strategy and the Environment, 29(1), 154–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carmine, S., & De Marchi, V. (2023). Reviewing paradox theory in corporate sustainability toward a systems perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 184(1), 139–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C. C. J. (2020). Sustainability orientation, green supplier involvement, and green innovation performance: Evidence from diversifying green entrants. Journal of Business Ethics, 161(2), 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chistov, V., Aramburu, N., Florit, M. E. F., Pena-Legazkue, I., & Weritz, P. (2023). Sustainability orientation and firm growth as ventures mature. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(8), 5314–5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarkson, M. E. (1995). A stakeholder framework for analyzing and evaluating corporate social performance. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 92–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Claudy, M. C., Peterson, M., & Pagell, M. (2016). The roles of sustainability orientation and market knowledge competence in new product development success. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33, 72–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifton, D., & Amran, A. (2011). The stakeholder approach: A sustainability perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 98(1), 121–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conard, B. R. (2013). Some challenges to sustainability. Sustainability, 5(8), 3368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosma, S., Schwizer, P. M., Nobile, L., & Leopizzi, R. (2021). Environmental attitude in the board. Who are the “green directors”? Evidences from Italy. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(7), 3360–3375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crisóstomo, V. L., De Souza Freire, F., & De Vasconcellos, F. C. (2011). Corporate social responsibility, firm value and financial performance in Brazil. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(2), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danso, A., Adomako, S., Lartey, T., Amankwah-Amoah, J., & Owusu-Yirenkyi, D. (2020). Stakeholder integration, environmental sustainability orientation and financial performance. Journal of Business Research, 119, 652–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De la Hoz-M, J., Fernández-Gómez, M. J., & Mendes, S. (2021). Ldashiny: An R package for exploratory review of scientific literature based on a Bayesian probabilistic model and machine learning tools. Mathematics, 9(14), 1671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delmas, M. A., Nairn-Birch, N., & Lim, J. (2015). Dynamics of environmental and financial performance: The case of greenhouse gas emissions. Organization and Environment, 28(4), 374–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1983). The iron cage revisited: Institutional isomorphism and collective rationality in organizational fields. American Sociological Review, 48(2), 147–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincer, B., Keskin, A. İ., & Dincer, C. (2023). Nexus between sustainability reporting and firm performance: Considering industry groups, accounting, and market measures. Sustainability, 15(7), 5849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobija, D., Arena, C., Kozlowski, L., Krasodomska, J., & Godawska, J. (2023). Towards sustainable development: The role of directors’ international orientation and their diversity for non-financial disclosure. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 30(1), 66–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, T., & Preston, L. E. (1995). The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review, 20(1), 65–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donthu, N., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., Pandey, N., & Lim, W. M. (2021). How to conduct a bibliometric analysis: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 133, 285–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, S. P. (2000). Fundamental uncertainty and the firm in the long run. Review of Political Economy, 12(4), 419–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durden, C. (2008). Towards a socially responsible management control system. Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, 21(5), 671–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dvorsky, J., Svihlikova, I., Kozubikova, L., Frajtova Michalikova, K., & Balcerzak, A. P. (2023). Effect of CSR implementation and crisis events in business on the financial management of SMEs. Technological and Economic Development of Economy, 29(5), 1496–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eccles, R. G., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2014). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. Management Science, 60(11), 2835–2857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elkington, J. (1997). Cannibals with forks: The triple bottom line of 21st century business. New Society. [Google Scholar]

- Emamisaleh, K., & Taimouri, A. (2021). Sustainable supply chain management drivers and outcomes: An emphasis on strategic sustainability orientation in the food industries. Independent Journal of Management & Production, 12(1), 282–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, P., Doronzo, E., & Dicorato, S. L. (2023). The financial and green effects of cultural values on mission drifts in European social enterprises. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(1), 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatoki, O. (2019). Green entrepreneurial orientation and firm performance in South Africa. Entrepreneurship and Sustainability Issues, 7(1), 247–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E. (1984). Strategic management: A stakeholder approach. In Business ethics quarterly (Vol. 4, Issue 4). Pitman. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman, R. E., Dmytriyev, S. D., & Phillips, R. A. (2021). Stakeholder theory and the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1757–1770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frerichs, I. M., & Teichert, T. (2023). Research streams in corporate social responsibility literature: A bibliometric analysis. Management Review Quarterly, 73(1), 231–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freudenreich, B., Lüdeke-Freund, F., & Schaltegger, S. (2020). A stakeholder theory perspective on business models: Value creation for sustainability. Journal of Business Ethics, 166(1), 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance and Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Funtowicz, S., Ravetz, J., & O’Connor, M. (1998). Challenges in the use of science for sustainable development. International Journal of Sustainable Development, 1(1), 99–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassim, B., & Bogers, M. (2019). Linking stakeholder engagement to profitability through sustainability-oriented innovation: A quantitative study of the minerals industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 224, 905–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez-Ramos, M. I., Donate, M. J., & Guadamillas, F. (2023). The interplay between corporate social responsibility and knowledge management strategies for innovation capability development in dynamic environments. Journal of Knowledge Management, 27(11), 59–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hahn, T., Figge, F., Pinkse, J., & Preuss, L. (2018). A paradox perspective on corporate sustainability: Descriptive, instrumental, and normative aspects. Journal of Business Ethics, 148(2), 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haldar, S. (2019). Towards a conceptual understanding of sustainability-driven entrepreneurship. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(6), 1157–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, Y., Sarfraz, M., Khalid, R., Ozturk, I., & Tariq, J. (2022). Does corporate social responsibility and green product innovation boost organizational performance? A moderated mediation model of competitive advantage and green trust. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istrazivanja, 35(1), 5379–5399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. L. (1995). A natural-resource-based view of the firm. Academy of Management Review, 20(4), 986–1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hart, S. L., & Dowell, G. (2011). A natural-resource-based view of the firm: Fifteen years after. Journal of Management, 37(5), 1464–1479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helfat, C. E., & Peteraf, M. A. (2003). The dynamic resource-based view: Capability lifecycles. Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 997–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herli, M., Tjahjadi, B., & Hamidah, H. (2024). Business sustainability practices and financial performance in the creative economy sector in Indonesia: Moderating role of power distance and long-term orientation. Intangible Capital, 20(3), 531–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herold, D. M. (2018). Demystifying the link between institutional theory and stakeholder theory in sustainability reporting. Economics, Management and Sustainability, 3(2), 6–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hess, M. F., & Hess, A. M. (2016). Stakeholder-driven strategic renewal. International Business Research, 9(3), 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hitt, M. A., Arregle, J. L., & Holmes, R. M. (2021). Strategic management theory in a post-pandemic and non-ergodic world. Journal of Management Studies, 58(1), 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, P., Jagani, S., Kim, J., & Youn, S. H. (2019). Managing sustainability orientation: An empirical investigation of manufacturing firms. International Journal of Production Economics, 211, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, I., Chirico, A., & Ranalli, F. (2022). Corporate strategies oriented towards sustainable governance: Advantages, managerial practices and main challenges. Journal of Management & Governance, 26(1), 75–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Issa, A., & Hanaysha, J. R. (2023). Breaking the glass ceiling for a sustainable future: The power of women on corporate boards in reducing ESG controversies. International Journal of Accounting and Information Management, 31(4), 623–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagani, S., & Hong, P. (2022). Sustainability orientation, byproduct management and business performance: An empirical investigation. Journal of Cleaner Production, 357, 131707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Járfás, Z. (2023). Reconcile the paradox: Stability & volatility inclusive. European Journal of Studies in Management and Business, 26, 24–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, M. K., & Rangarajan, K. (2020). Analysis of corporate sustainability performance and corporate financial performance causal linkage in the Indian context. Asian Journal of Sustainability and Social Responsibility, 5(1), 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joglekar, N., & Phadnis, S. (2021). Accelerating supply chain scenario planning. MIT Sloan Management Review, 62(2), 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Karman, A., & Savaneviciene, A. (2021). Enhancing dynamic capabilities to improve sustainable competitiveness: Insights from research on organisations of the Baltic region. Baltic Journal of Management, 16(2), 318–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R. U., Richardson, C., & Salamzadeh, Y. (2022). Spurring competitiveness, social and economic performance of family-owned SMEs through social entrepreneurship; a multi-analytical SEM & ANN perspective. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 184, 122047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizar, H. M. U., Iqbal, M. J., Khalid, J., & Adomako, S. (2022). Addressing the conceptualization and measurement challenges of sustainability orientation: A systematic review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 142, 718–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khizar, H. M. U., Iqbal, M. J., & Rasheed, M. I. (2021). Business orientation and sustainable development: A systematic review of sustainability orientation literature and future research avenues. Sustainable Development, 29(5), 1001–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A. A. (2025). Do sustainable companies have better financial performance? Revisiting a seminal study. Journal of Management Scientific Reports, 3(2), 88–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiran, M., Chughtai, S., & Naeem, M. A. (2024). Navigating greenwashing in the G8: Insights into family-owned firms, technology innovation, and economic policy uncertainty. Research in International Business and Finance, 71, 102481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, S. P., Spieth, P., & Heidenreich, S. (2021). Facilitating business model innovation: The influence of sustainability and the mediating role of strategic orientations. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 38(2), 271–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuckertz, A., & Wagner, M. (2010). The influence of sustainability orientation on entrepreneurial intentions—Investigating the role of business experience. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(5), 524–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linnenluecke, M. K., Marrone, M., & Singh, A. K. (2020). Conducting systematic literature reviews and bibliometric analyses. Australian Journal of Management, 45(2), 175–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maier, D., Waldherr, A., Miltner, P., Wiedemann, G., Niekler, A., Keinert, A., Pfetsch, B., Heyer, G., Reber, U., Häussler, T., Schmid-Petri, H., & Adam, S. (2018). Applying LDA topic modeling in communication research: Toward a valid and reliable methodology. Communication Methods and Measures, 12(2–3), 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meder, D., Rabe, F., Morville, T., Madsen, K. H., Koudahl, M. T., Dolan, R. J., Siebner, H. R., & Hulme, O. J. (2021). Ergodicity-breaking reveals time optimal decision making in humans. PLoS Computational Biology, 17(9), e1009217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer, J. W., & Rowan, B. (1977). Institutionalized organizations: Formal structure as myth and ceremony. American Journal of Sociology, 83(2), 340–363. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778293 (accessed on 12 March 2025). [CrossRef]

- Meyer, R. E., & Höllerer, M. A. (2014). Does institutional theory need redirecting? Journal of Management Studies, 51(7), 1221–1233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitroff, I. I., & Alpaslan, M. C. (2003). Preparing for evil. Harvard Business Review, 81(4), 109–124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Mo, Y., Liao, K., & Wang, J. (2024). Analysis of current research in the field of sustainable employment based on latent dirichlet allocation. Sustainability, 16(11), 4557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., Antes, G., Atkins, D., Barbour, V., Barrowman, N., Berlin, J. A., Clark, J., Clarke, M., Cook, D., D’Amico, R., Deeks, J. J., Devereaux, P. J., Dickersin, K., Egger, M., Ernst, E., Gøtzsche, P. C., … Tugwell, P. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Myeni, T. P., & Singh, P. (2024). Implementing B-BBEE: Leader experiences in the South African banking industry. SA Journal of Human Resource Management, 22, a2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasta, L., Magnanelli, B. S., & Ciaburri, M. (2024). From profits to purpose: ESG practices, CEO compensation and institutional ownership. Management Decision, 62(13), 46–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nelling, E., & Webb, E. (2009). Corporate social responsibility and financial performance: The “virtuous circle” revisited. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 32(2), 197–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, D. C. (1999). Dealing with a non-ergodic world: Institutional economics, property rights, and the global environment. Duke Environmental Law & Policy Forum, X(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Nwoba, A. C., Boso, N., & Robson, M. J. (2021). Corporate sustainability strategies in institutional adversity: Antecedent, outcome, and contingency effects. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 787–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ononye, U., Ndudi, F., Aloamaka, J., Mba, M., & Ejumudo, T. (2022). Examining the role of quality performance and entrepreneurial orientation on green manufacturing and financial performance. Environmental Economics, 13(1), 50–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., & McKenzie, J. E. (2022). Introduction to PRISMA 2020 and implications for research synthesis methodologists. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(2), 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pagell, M., & Wu, Z. (2009). Building a more complete theory of sustainable supply chain management using case studies of 10 exemplars. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 45(2), 37–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pahlevan-Sharif, S., Mura, P., & Wijesinghe, S. N. R. (2019). A systematic review of systematic reviews in tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management, 39, 158–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, B. L., Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Purnell, L., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. The Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasamar, S., Bornay-Barrachina, M., & Morales-Sánchez, R. (2023). Institutional pressures for sustainability: A triple bottom line approach. European Journal of Management and Business Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Penrose, E. (1959). Theory of the growth of the firm: Chapters 1, 2, and 5. Basil Blackwell, Oxford. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, O. (2019). The ergodicity problem in economics. Nature Physics, 15(12), 1216–1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, R. E., & Sevillano, F. J. M. (2025). Business sustainability and its effect on performance measures: A comprehensive analysis. Sustainability, 17(1), 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinzon-Castro, S. Y., & Maldonado-Guzman, G. (2023). Effects of sustainable culture on CSR and financial performance in manufacturing industry. Retos-Revista de Ciencias de la Administracion y Economia, 13(26), 191–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajnoha, R., Lesníková, P., & Korauš, A. (2016). From financial measures to strategic performance measurement system and corporate sustainability: Empirical evidence from Slovakia. Economics and Sociology, 9(4), 134–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajnoha, R., Lesníková, P., & Krajčík, V. (2017). Influence of business performance measurement systems and corporate sustainability concept to overal business performance: “Save the planet and keep your performance”. E + M Ekonomie a Management, 20(1), 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roxas, B., Ashill, N., & Chadee, D. (2017). Effects of entrepreneurial and environmental sustainability orientations on firm performance: A study of small businesses in the Philippines. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(S1), 163–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlosser, R. W., Wendt, O., & Sigafoos, J. (2007). Not all systematic reviews are created equal: Considerations for appraisal. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention, 1(3), 138–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoemaker, P. J. H., Heaton, S., & Teece, D. (2018). Innovation, dynamic capabilities, and leadership. California Management Review, 61(1), 15–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, W. R. (2008). Institutions and organizations: Ideas and interests. SAGE Publications, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Scott, W. R., Smith, K. G., & Hitt, M. A. (2004). Institutional theory: Contributing to a theoretical research program. In Great minds in management: The process of theory development. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- She, C., & Michelon, G. (2023). A governance approach to stakeholder engagement in sustainable enterprises-Evidence from B Corps. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(8), 5487–5505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sine, W. D., Cordero, A. M., & Coles, R. S. (2022). Entrepreneurship through a unified sociological neoinstitutional lens. Organization Science, 33(4), 1675–1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, Z. (2016). Sustainable development goals: Challenges and opportunities. Indian Journal of Public Health, 60(4), 247–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soo Sung, C., & Park, J. Y. (2018). Sustainability orientation and entrepreneurship orientation: Is there a tradeoff relationship between them? Sustainability, 10(2), 379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straková, J. (2015). Sustainable value added as we do not know it. Business: Theory and Practice, 16(2), 168–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardin, M. G., Perin, M. G., Simões, C., & Braga, L. D. (2024). Organizational sustainability orientation: A review. Organization and Environment, 37(2), 298–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28(13), 1319–1350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turkes, M. C. (2024). Driving success: Unveiling the synergy of e-marketing, sustainability, and technology orientation in online SME. Journal of Theoretical and Applied Electronic Commerce Research, 19(2), 1411–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. (2024). Progress towards the sustainable development goals: Report of the secretary-general. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/files/report/2024/SG-SDG-Progress-Report-2024-advanced-unedited-version.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- Valdez-Juarez, L. E., Ramos-Escobar, E. A., Hernandez-Ponce, O. E., & Ruiz-Zamora, J. A. (2024). Digital transformation and innovation, dynamic capabilities to strengthen the financial performance of Mexican SMEs: A sustainable approach. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1), 2318635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vallet-Bellmunt, T., Del-Corte-Lora, V., & Martínez-Fernández, M. T. (2024). Do we have to choose between economic or environmental performance? The case of the ceramic industry cluster. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(6), 5815–5836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagenhofer, A. (2024). Sustainability reporting: A financial reporting perspective. Accounting in Europe, 21(1), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wale, L. E. (2015). Board diversity, external governance, ownership structure and performance in Ethiopian microfinance institutions. Corporate Ownership and Control, 12(3), 190–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, L., & Kanbach, D. K. (2022). Toward an integrated framework of corporate venturing for organizational ambidexterity as a dynamic capability. Management Review Quarterly, 72(4), 1129–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willmott, H. (2015). Why institutional theory cannot be critical. Journal of Management Inquiry, 24(1), 105–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L., Subramanian, N., Gunasekaran, A., Abdulrahman, M. D.-A., Pawar, K. S., & Doran, D. (2018). A two-dimensional, two-level framework for achieving corporate sustainable development: Assessing the return on sustainability initiatives. Business Strategy and the Environment, 27(8), 1117–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Y., & Demirel, P. (2023). The impact of sustainability-oriented dynamic capabilities on firm growth: Investigating the green supply chain management and green political capabilities. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(8), 5873–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuen, M. K., Ngo, T., Le, T. D. Q., & Ho, T. H. (2022). The environment, social and governance (ESG) activities and profitability under COVID-19: Evidence from the global banking sector. Journal of Economics and Development, 24(4), 345–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zetzsche, D. A., & Anker-Sorensen, L. (2022). Regulating sustainable finance in the dark. European Business Organization Law Review, 23(1), 47–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zubeltzu-Jaka, E., Álvarez-Etxeberria, I., & Aldaz-Odriozola, M. (2024). Corporate social responsibility oriented boards and triple bottom line performance: A meta-analytic study. Business Strategy and Development, 7(1), e320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zumente, I., & Bistrova, J. (2021). Esg importance for long-term shareholder value creation: Literature vs. practice. Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 7(2), 127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No. | Definition |

|---|---|

| 1 | …a modern approach that involves expanding the economic dimensions of the enterprise’s activity by incorporating environmental protection measures and social responsibility (Turkes, 2024). |

| 2 | …the integration of economic, environmental, and social orientation (Jagani & Hong, 2022). |

| 3 | …a strategic resource, which can lead to competitive advantage and superior (financial) performance (Claudy et al., 2016). |

| 4 | …not merely for a firm’s long-term survival, but also for preservation of social ecosystems at large (Hong et al., 2019). |

| 5 | …a combination of economic, green, and social/ethical motives (Haldar, 2019). |

| 6 | …the level of concern about the environmental protection and social responsibility of individuals, and consists of items that measure the underlying attitudes and personal traits on environmental protection and social responsibility (Kuckertz & Wagner, 2010). |

| 7 | …becomes integrated in the organisation when the organisation has both a managerial orientation toward sustainability and an innovation capability (Pagell & Wu, 2009). |

| 8 | …illustrates how sustainability factors and issues are executed and performed at an organisation (Emamisaleh & Taimouri, 2021). |

| 9 | …the culture, principles, and behaviours that helps firms commit to the creation of superior sustainable practices and efficiently invest resources necessary to develop appropriate new green products, leading to superior green innovation performance (Cheng, 2020). |

| 10 | …linked to environmental performance, while social capital and organisational resilience are linked to economic performance (Vallet-Bellmunt et al., 2024). |

| 11 | …considered as an organisational resource and a dynamic capability that can yield competitive advantage and superior firm performance (Khizar et al., 2022). |

| Theory Name | Single Theory Application | Multi-Theory Application | Total Theory Application | % of Reviewed Studies |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stakeholder Theory | 8 | 28 | 36 | 30.8% |

| Resource-Based Theory | 4 | 13 | 18 | 15.5% |

| Institutional Theory | 4 | 8 | 12 | 10.4% |

| Natural Resource-Based View | 2 | 7 | 9 | 7.9% |

| Upper Echelons Theory | 3 | 5 | 8 | 7.1% |

| Agency Theory | 1 | 6 | 7 | 6.3% |

| Legitimacy Theory | 0 | 7 | 7 | 6.3% |

| Dynamic Capabilities Theory | 2 | 5 | 7 | 6.4% |

| Stewardship Theory | 2 | 2 | 4 | 3.7% |

| Resource Dependency Theory | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2.8% |

| Signalling Theory | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2.8% |

| Neoclassical Economic Theory | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2.8% |

| Theory and Impact on Sustainability Orientation | Focus | Key Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Resource-Based Theory: inside-out | Firm’s internal resources and capabilities (Barney, 1991; Penrose, 1959) | Unique value creation, innovation, competitive advantage |

| Institutional Theory: outside-in | External institutions and societal norms (DiMaggio & Powell, 1983; J. W. Meyer & Rowan, 1977) | Compliance, legitimacy, norms, sector-wide change |

| Stakeholder Theory: inside-out and outside-in | Stakeholder interests and relationships (Clarkson, 1995; Freeman, 1984) | Ethical responsibility, performance improvement |

| Description | Results |

|---|---|

| Timespan (years) | 2008:2024 |

| Sources (number of journals) | 78 |

| Articles (number) | 117 |

| Annual growth rate (%) | 23.7 |

| Article average age (years) | 3.4 |

| Average citations per article (number) | 50.2 |

| Keywords (number of keywords plus the author’s keywords) | 925 |

| Authors (number) | 360 |

| Single-authored articles (number) | 13 |

| Co-Authors per article (number) | 3.3 |

| International co-authorships (%) | 40.2 |

| Category Name | Topic Name and ID |

|---|---|

| Sustainability and sustainability orientation as a concept | Sustainability Orientation (Topics 16 and 11) |

| Structural Equation (Topic 2) | |

| Corporate Sustainability (Topic 1) | |

| Environmental dimension | Environmental Disclosure and Performance (Topics 10 and 13) |

| Oriented Innovation (Topic 5) | |

| Social dimension | Gender Diversity (Topic 8) |

| Corporate Social (Topic 7) and Social Responsibility (Topic 6) | |

| Stakeholder Engagement (Topic 4) | |

| Economic dimension | Business Performance (Topic 3) |

| Bank Performance (Topic 12) | |

| Financial performance | Financial Performance (Topics 14, 15 and 17) |

| Sustainable Performance (Topic 9) |

| Characteristic | Ergodic World | Non-Ergodic World | Implications for Firms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictability | Relatively high; past data reliably predict the future | Relatively low; past data are less reliable for future predictions | Traditional forecasting methods may be less effective; scenario planning and agility are needed. |

| Equilibrium | Stable, predictable long-term equilibrium | Lack of stable, predictable long-term equilibrium | Cannot expect a return to pre-disruption states; continuous adaptation is required. |

| Role of the past | Significant; used for forecasting and planning | Limited disruptions create new contexts and the new business-as-usual environment | Historical data are less reliable; real-time monitoring and learning are needed. |

| Nature of change | Gradual, incremental | Rapid, discontinuous, and interconnected | Organisations must be flexible and responsive to sudden shifts and cascading effects. |

| Focus of strategy | Long-term static planning based on predictions | Dynamic adaptation and building resilience | Shift from rigid plans to agile strategizing and the ability to evolve and adjust. |

| Implications | Emphasis on efficiency and optimisation | Focus on adaptability, resilience, and learning | Building dynamic capabilities becomes paramount for survival and sustained competitive advantage. |

| Theoretical Proposition | Topic Theme | Future Research Questions |

|---|---|---|

| A clearly defined and strategically integrated SO is a strategic resource and internal capability that promotes innovation, value creation, and long-term resilience against environmental, social, and economic disruptions. | Sustainability orientation (Topics 16 and 11) | 1. How does the impact of SO on FP vary across industries, sectors, cultural contexts or market conditions? |

| Structural equation (Topic 2) | 2. What are the key mediating factors through which SO affects financial outcomes? | |

| Corporate sustainability (Topic 1) | 3. Under what conditions (e.g., firm size, leadership commitment, culture, etc.) does integrating sustainability into strategy yield financial benefits? | |

| In a world of green policy and commitment reversals and escalating environmental disruptions, firms that proactively embed environmental SD into corporate governance, strategic planning, and reporting frameworks are more adept at maintaining legitimacy and operational resilience. | Environmental disclosure and performance (Topics 10 and 13) | 1. How do different cultural or regulatory contexts influence the effectiveness of sustainability transparency and disclosures? |

| Oriented innovation (Topic 5) | 2. How does sustainability-driven innovation contribute to environmental performance and long-term firm adaptability to natural disasters? | |

| Firms that prioritise social responsibility and actively engage with stakeholders, promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion, can enhance stakeholder trust and robust reputational resilience in a world of growing political tensions, military conflicts, and social disasters. | Gender diversity (Topic 8) | 1. How do diversity, equity and inclusivity on boards influence the implementation and outcomes of sustainability-oriented initiatives? |

| Corporate social responsibility (Topic 6 and 7) | 2. To what extent do proactive CSR initiatives translate into FP improvements, and how do stakeholder expectations or industry characteristics impact it? | |

| Stakeholder engagement (Topic 4) | 3. What forms of stakeholder engagement most effectively translate SO into reputational resilience? 4. How does corporate governance impact the relationship between SO and FP? | |

| Firms can leverage SO to gain a competitive advantage and bolster their resilience against macroeconomic shocks and induced disruptions caused by sudden policy changes, geopolitical tensions, and trade wars. | Business performance (Topic 3) | 1. What internal business processes are most enhanced by SO, and how do they influence economic performance? |

| Bank performance (Topic 12) | 2. How does the SO influence FP, risk management, and disclosure, and what role do financial intermediaries play? | |

| The financial advantages of SO are not immediate and are contingent upon context and firms’ capacity to effectively utilise their dynamic capabilities and external expectations. | Financial performance (Topics 14, 15 and 17) | 1. How does the SO implementation affect measurable financial outcomes? |

| Sustainable performance (Topic 9) | 2. What composite metrics can capture SD performance across economic, environmental, and social dimensions in a non-ergodic world? |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sedovs, E.; Volkova, T.; Ludviga, I. Does Sustainability Orientation Drive Financial Success in a Non-Ergodic World? A Systematic Literature Review. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060339

Sedovs E, Volkova T, Ludviga I. Does Sustainability Orientation Drive Financial Success in a Non-Ergodic World? A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060339

Chicago/Turabian StyleSedovs, Edgars, Tatjana Volkova, and Iveta Ludviga. 2025. "Does Sustainability Orientation Drive Financial Success in a Non-Ergodic World? A Systematic Literature Review" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060339

APA StyleSedovs, E., Volkova, T., & Ludviga, I. (2025). Does Sustainability Orientation Drive Financial Success in a Non-Ergodic World? A Systematic Literature Review. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 339. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060339