Sophisticated Capital Budgeting Decisions for Financial Performance and Risk Management—A Tale of Two Business Entities

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Conceptualizing Capital Budgeting (CB)

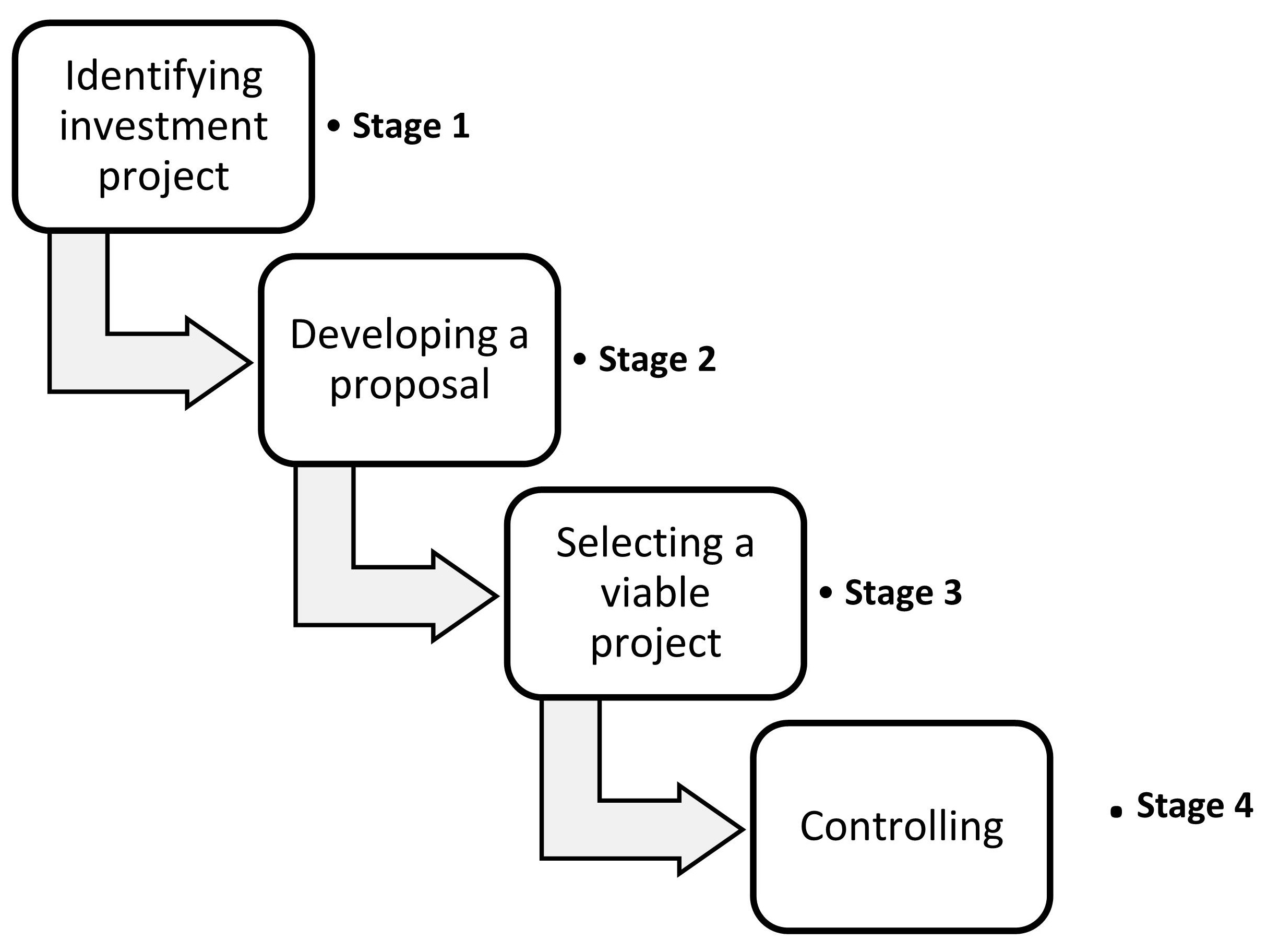

2.2. CB Process and Techniques

2.3. CBDs of Global Firms

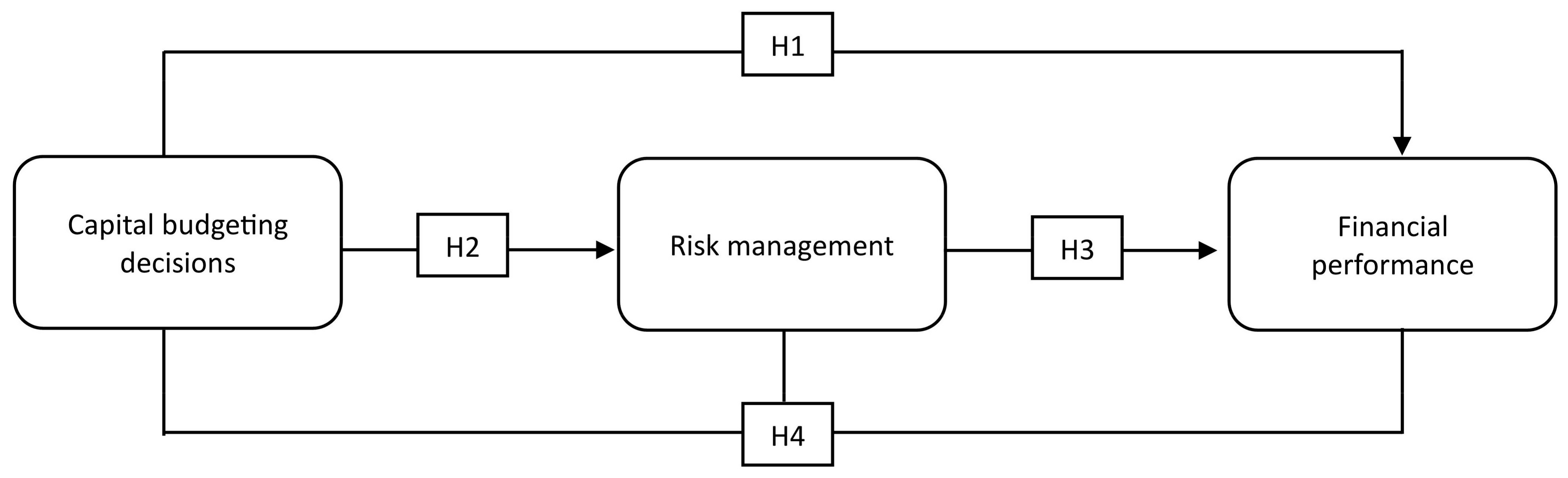

2.4. Hypothesis Development

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Sampling

3.2. Experimental Variables

3.3. Data Analysis

4. Findings and Discussion

5. Conclusions

5.1. Research Implications

5.2. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANPV | Annualized net present value |

| ARR | Accounting/average rate of return |

| CB | Capital budgeting |

| CBDs | Capital budgeting decisions |

| FP | Financial performance |

| GMM | Generalized method of moments |

| IRR | Internal rate of return |

| RM | Risk management |

| SCBDs | Sophisticated capital budgeting decisions |

| SMEs | Small and medium enterprises |

| MNCs | Multinational corporations |

| NPV | Net present value |

| PBM | Payback method |

| PI | Profitability index |

| RADRs | Risk-adjusted discount rates |

| RBV | Resource-based view |

References

- Akalu, M. M. (2003). The process of investment appraisal: The experience of 10 large British and Dutch companies. International Journal of Project Management, 21(5), 355–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Hashimy, H. N. H. (2025). The relationship between financial management strategies and firm financial performance: The moderating role of firm size. Journal of Financial Management of Property and Construction. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alles, L., Jayathilaka, R., Kumari, N., Malalathunga, T., Obeyesekera, H., & Sharmila, S. (2021). An investigation of the usage of capital budgeting techniques by small and medium enterprises. Quality & Quantity, 55, 993–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeida, R. P., Ayala, N. F., Benitez, G. B., Kliemann Neto, F. J., & Frank, A. G. (2023). How to assess investments in industry 4.0 technologies? A multiple-criteria framework for economic, financial, and sociotechnical factors. Production Planning & Control, 34(16), 1583–1602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andon, P., Baxter, J., & Chua, W. F. (2024). Affect and reason in uncertain accounting settings: The case of capital investment appraisal. Accounting & Finance, 64(2), 1439–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrés-Sánchez, J. D. (2025). A systematic overview of fuzzy-random option pricing in discrete time and fuzzy-random binomial extension sensitive interest rate pricing. Axioms, 14(1), 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, J., Butt, I., & Ahmad, N. (2025). SMEs’ strategic orientation through Miles and Snow typology: A synthesis of literature and future directions. Management Research Review, 48(2), 258–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Añón Higón, D., Máñez, J. A., Sanchis, A., & Sanchis, J. A. (2025). Digitalisation and global value chain participation: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms. Industry and Innovation, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, M., & Bond, S. (1991). Some tests of specification for panel data: Monte Carlo evidence and an application to employment equations. The Review of Economic Studies, 58(2), 277–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asian Development Bank. (2022). ADB Asia SME monitor—Indonesia. Available online: https://data.adb.org/media/13281/download (accessed on 16 April 2024).

- Barbieri, G., Vega, A. S., Gutierrez, J., Laserna, J., & Mateus, L. M. (2025). Strategic capital investments in asset management: A value-based approach. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, 31(5), 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batra, R., & Verma, S. (2017). Capital budgeting practices in Indian companies. IIMB Management Review, 29(1), 29–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battalio, R. H., Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2024). How managers communicate about capital budgeting to investors. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4766530 (accessed on 24 April 2024).

- Beckett-Camarata, J. (2003). An examination of the relationship between the municipal strategic plan and the capital budget and its effect on financial performance. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 15(1), 23–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, Y., & Marzo, G. (2011). Decision making using behavioral finance for capital budgeting. In K. Baker, & P. English (Eds.), Capital budgeting valuation: Financial analysis for today’s investment decisions (pp. 421–444). John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Bogsnes, B. (2023). Beyond budgeting and dynamic resource allocation. Controlling & Management Review, 67(6), 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollen, K. A. (1996). An alternative two stage least squares (2SLS) estimator for latent variable equations. Psychometrika, 61(1), 109–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bring, J. (1994). How to standardize regression coefficients. The American Statistician, 48(3), 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, J. Y., Stein, J. C., & Wu, A. A. (2024). Economic budgeting for endowment-dependent universities (No. w32506). National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cassone, D. (2024). Budgeting for your organization. In Leadership concepts for the engineering mindset (pp. 55–64). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cetingoz, A. R., Fermanian, J. D., & Guéant, O. (2024). Risk Budgeting portfolios: Existence and computation. Mathematical Finance, 34(3), 896–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charoenwong, B., Kimura, Y., Kwan, A., & Tan, E. (2024). Capital budgeting, uncertainty, and misallocation. Journal of Financial Economics, 153, 103779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danielson, M. G., Hogan, K. M., & Olson, G. T. (2024). Shareholder theory, stakeholder theory, and the capital budgeting decision. Corporate Ownership & Control, 21(2), 37–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Driscoll, J., & Kraay, A. C. (1998). Consistent covariance matrix estimation with spatially dependent data. Review of Economics and Statistics, 80, 549–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermasova, N. (2020). 35 years of public capital budgeting: A review and future research agenda. Public Finance and Management, 19(4), 297–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farragher, E. J., Kleiman, R. T., & Sahu, A. P. (2001). The association between the use of sophisticated capital budgeting practices and corporate performance. The Engineering Economist, 46(4), 300–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C., Fei, W., Rui, Y., & Yan, L. (2021). International investment with exchange rate risk. Asia-Pacific Journal of Accounting & Economics, 28(2), 225–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrison, R. H., Noreen, E. W., & Brewer, P. C. (2021). Managerial accounting. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, P. J., & Sathye, M. (2020). The relationship between national culture, capital budgeting systems and firm financial performance: Evidence from Australia and Indonesia. International Journal of Management Practice, 13(6), 650–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gujarati, D. N. (2021). Essentials of econometrics. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Gujarati, D. N., & Porter, D. C. (2009). Basic econometrics. McGraw-Hill. [Google Scholar]

- Haka, S. F., Gordon, L. A., & Pinches, G. E. (1985). Sophisticated capital budgeting selection technique and firms’ performance. The Accounting Review, 60(4), 651–669. [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann, M., & Weißenberger, B. E. (2024). Decision-making in the capital budgeting context: Effects of type of decision aid and increases in information load. Journal of Business Economics, 94(2), 379–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, A. D., Johnson, S. G., Greco, L. M., O’Boyle, E. H., & Walter, S. L. (2020). Endogeneity: A review and agenda for the methodology-practice divide affecting micro and macro research. Journal of Management, 47(1), 105–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunjra, A. I., Arunachalam, M., Verhoeven, P., Colombage, S., & Bouri, E. (2024). The interplay of CSR, stakeholder interest management, capital budgeting, and firm performance. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 43, 100967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1979). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. In K. Brunner (Ed.), Economics social institutions. Rochester studies in economics and policy issues (Vol. 1). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, W. Y. (2022). Internal Capital Budgeting and Allocation in Financial Firms. In C. F. Lee, & A. C. Lee (Eds.), Encyclopedia of finance. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khajavi, S., Etemedy Jooriaby, M., & Kermani, E. (2024). Budgeting in healthcare. In T. Allahviranloo, F. Hosseinzadeh Lotfi, Z. Moghaddas, & M. Vaez-Ghasemi (Eds.), Decision making in healthcare systems. Studies in systems, decision and control (Vol. 513). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, A. (2024). Capital budgeting and improvement process. In Fundamentals of public budgeting and finance. Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H. T., & Nguyen, Q. (2025). Managers’ risk preferences and firm investment: The moderating role of early-life war exposure and firm size. International Journal of Finance & Economics. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleibergen, F., & Paap, R. (2006). Generalized reduced rank tests using the singular value decomposition. Journal of Econometrics, 133(1), 97–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazim, N. A. M., Ariffin, S. H. S., & Khair, Z. (2025). Asia’s tiger economies and beyond: Project management views from Asian institutions. In Project management for European, Asian and African practitioners—Theory and technique examples in selected professions (pp. 185–214). Springer Nature. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leitner, S. (2024). Corporate investment: Advancing theoretical perspectives using agent-based techniques. In F. Wall, S. H. Chen, & S. Leitner (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of agent-based computational management science. Oxford Academic. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leon, F. M., Isa, M., & Kester, G. W. (2008). Capital budgeting practices of listed Indonesian companies. Asian Journal of Business and Accounting, 1(2), 175–192. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W., Li, W., Seppänen, V., & Koivumäki, T. (2023). Effects of greenwashing on financial performance: Moderation through local environmental regulation and media coverage. Business Strategy and the Environment, 32(1), 820–841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mollah, M. A. S., Rouf, M. A., & Rana, S. S. (2023). A study on capital budgeting practices of some selected companies in Bangladesh. PSU Research Review, 7(2), 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota, J., & Moreira, A. C. (2023). Capital Budgeting Practices: A Survey of Two Industries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(3), 191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunden, N., Abbana, S., Marimuthu, F., & Sentoo, N. (2022). An assessment of management skills on capital budgeting planning and practices: Evidence from the small and medium enterprise sector. Cogent Business & Management, 9(1), 2136481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurullah, M., & Kengatharan, L. (2015). Capital budgeting practices: Evidence from Sri Lanka. Journal of Advances in Management Research, 12(1), 55–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. (2022). Financing SMEs and entrepreneurs 2022: An OECD scoreboard. Available online: https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/13753156-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/13753156-en (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Peel, M. J., & Bridge, J. (1998). How planning and capital budgeting improve SME performance. Long Range Planning, 31(6), 848–856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, P., & Fabozzi, F. (2002). Capital budgeting: Theory and practice. John Wiley and Sons. Available online: https://www.wiley.com/en-au/Capital+Budgeting%3A+Theory+and+Practice-p-9780471218333 (accessed on 13 April 2024).

- Purnamasari, P., & Adriza. (2024). Capital budgeting techniques and financial performance: A comparison between SMEs and large listed firms. Cogent Economics & Finance, 12(1), 2404707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puwanenthiren, P. (2024). National development level effects on capital budgeting practices: A comparative study of nature vs nurture. PSU Research Review, 8(1), 227–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quirin, G. D. (1967). The capital expenditure decision. Irwin, R.D. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, P., Kumar, S., Chavan, M., & Lim, W. M. (2021). A systematic literature review on SME financing: Trends and future directions. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(3), 1247–1277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryan, P. A., & Ryan, G. P. (2002). Capital budgeting practices of the Fortune 1000: How have things changed. Journal of Business and Management, 8(4), 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seddiki, B. (2025). Revolutionizing project control: Leveraging control theory for integrated cost, schedule, and risk management. Discover Civil Engineering, 2(1), 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segelod, E. (1998). Capital budgeting in a fast-changing world. Long Range Planning, 31(4), 529–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, J. F., Bilsky, B. A., & Shelleman, J. M. (2024). SMEs, Sustainability, and Capital Budgeting. Small Business Institute Journal, 20(1), 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureka, R., Kumar, S., Colombage, S., & Abedin, M. Z. (2022). Five decades of research on capital budgeting—A systematic review and future research agenda. Research in International Business and Finance, 60, 101609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sureka, R., Kumar, S., Mukherjee, D., & Theodoraki, C. (2023). What restricts SMEs from adopting sophisticated capital budgeting practices? Small Business Economics, 60(1), 265–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeeten, F. H. M. (2006). Do organizations adopt sophisticated capital budgeting practices to deal with uncertainty in the investment decision? A research note. Management Accounting Research, 17(1), 106–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vonlanthen, J. (2024). On the determinants of discount rates in discounted cash flow valuations: A counterfactual analysis. Real Estate, 1(2), 174–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S. Y., & Lee, C. F. (2021). A fuzzy real option valuation approach to capital budgeting under uncertainty environment. In C. F. Lee, & A. C. Lee (Eds.), Encyclopedia of finance. Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolf, A. (2025). Public support for the roll-out of renewable hydrogen in Europe: A real options perspective. International Journal of Hydrogen Energy, 97, 1440–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2024). Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) finance. Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (2021). Five key insights on the future-readiness of SMEs. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2021/12/5-key-insights-on-the-future-readiness-of-smes/ (accessed on 20 March 2025).

- Yu, J., Zhang, Z., Chen, X., & Boward, R. (2025). Mapping government budgeting research: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Public Administration, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| SMEs | MNCs | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industries | N | % | Industries | N | % |

| Agriculture, forestry, and fisheries | 74 | 25.08 | Energy, oil, gas, and coal | 80 | 27.11 |

| Manufacturing | 52 | 17.62 | Agriculture and plantation | 59 | 20.00 |

| Transportation and communication | 48 | 16.27 | Real estate management and development | 48 | 16.27 |

| Construction | 45 | 15.25 | Apparel and luxury goods | 45 | 15.25 |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 43 | 14.57 | Food and beverages | 33 | 11.18 |

| Other services | 33 | 11.18 | Media and entertainment | 30 | 10.16 |

| Total | 295 | 100 | Total | 295 | 100 |

| Variables | Discussion | Estimation | Types | Symbol | Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sophisticated capital budgeting decisions | The theoretical analysis of extant literature established that both SMEs and MNCs implement SCBDs in their investment appraisals. | SCBDs of SMEs and MNCs are described and estimated through an index. Firms following SCBDs in their investment appraisals are assigned a score of ‘1’, and firms that do not follow SCBDs are assigned a score of ‘0’. The index value ranges from 0 to 590. A higher SCBD index value indicates the increasing use of SCBDs in investment appraisals. | Independent | SCBDs | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Risk management | Risk management in sampled SMEs and MNCs is represented by evaluating their effectiveness in managing liquidity and solvency risks. | Both liquidity and solvency risks are represented by two dummy variables. The dummy variable liquidity risk is estimated by the quick ratio (QR), which is used for analyzing the immediate ability of a firm to pay its short-term liabilities and measured by dividing a company’s most liquid assets, like cash, cash equivalents, marketable securities, and accounts receivable, by total current liabilities. Whilst SLR’s dummy is represented by Debt-to-Equity Ratio (DER) and it is estimated by dividing a firm’s total debt by its total equity. A higher DER implies the possibility of solvency risk. | Dependent | QR, DER | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Financial performance | Following the extant literature review, FP is quantified through ROA and ROE dummies. | ROA is evaluated by the ratio of earnings before tax divided by the total assets of the firm. A higher ROA ratio represents better FP, whereas a low ROA ratio implies reduced FP. Similarly, ROE is estimated by a ratio between profit after tax divided by the average core capital. A higher ROE ratio signifies an increase in FP, and a lower ROE ratio is an indicator of a reduction in the FP of a firm. | Dependent | ROA, ROE | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Size | The extant literature indicates that the size of the firm may affect the CBDs; therefore, it is essential to include this as a control variable in the empirical analysis of this study. | Size is measured by a dummy named SIZE, and it is evaluated by a ratio obtained by dividing the firm’s total assets by the average total assets of the respective industry of the firm. | Control | SIZE | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Sales | This control variable is likely to influence the CBDs as well as the FP of firms. | Sales are estimated by the dummy of annual growth in sales, represented by (SAL), and it is evaluated by the changes in real sales. | Control | SAL | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Operational risk | This variable may influence the measurement of the RM variable; therefore, it is applied as a control variable. | The operational risk (OPR) is represented by a proxy variable, and it is evaluated by the coefficient of changes in a firm’s income. | Control | OPR | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Capital intensity | This control variable is found to influence the RM and FP of firms and may affect the findings related to the relationship between CBDs and FP. | It is represented by a dummy of capital intensity ratio (CIR), and it is estimated by dividing a firm’s total assets by its total revenue. A higher CIR implies that a firm has a higher financial leverage, affecting the FP and RM of firms. | Control | CIR | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Degree of focus | Firms operating in a saturated industry with a large number of firms are likely to enjoy fewer financial benefits of CBDs, whereas firms operating in an industry with a smaller number of firms may enjoy more financial benefits of CBDs. | It is represented by a DOF dummy, and it is estimated by the ratio of the number of industries in which the firm is operating, divided by the average number of segments for the firms in the same industry. | Control | DOF | ± | OECD, ADB, OECD, annual reports |

| Variable | Mean | Median | Max. | Min. | SD | Skewness | Kurtosis | Jarque–Bera | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCBDs | 318.47 | 71.09 | 590 | 0 | 305.55 | 40.56 | 36.47 | 38.45 | 0.001 |

| LDR | 2.17 | 2.76 | 6.35 | 1.20 | 1.618 | 1.148 | 2.751 | 2.128 | 0.011 |

| SLR | 1.18 | 1.37 | 9.57 | 3.52 | 1.235 | 2.470 | 4.385 | 3.651 | 0.001 |

| ROA | 1.32 | 1.44 | 4.79 | 2.53 | 1.81 | 1.408 | 2.157 | 2.475 | 0.001 |

| ROE | 5.25 | 5.56 | 6.71 | 1.47 | 4.87 | 1.348 | 2.447 | 1.523 | 0.001 |

| SIZE | 35.69 | 36.64 | 77.84 | 11.24 | 22.569 | 7.417 | 9.625 | 18.749 | 0.001 |

| SAL | 20.98 | 18.34 | 45.75 | 9.48 | 8.394 | 9.494 | 11.394 | 8.403 | 0.001 |

| OPR | 6.49 | 6.95 | 7.48 | 1.39 | 1.484 | 0.454 | 0.584 | 0.494 | 0.000 |

| CIR | 22.49 | 23.28 | 30.45 | 6.49 | 7.589 | 5.302 | 5.139 | 2.494 | 0.001 |

| DOF | 3.29 | 3.22 | 6.37 | 1.39 | 0.853 | 0.663 | 1.113 | 1.484 | 0.001 |

| Variables | SCBDs | LDR | SLR | ROA | ROE | SIZE | SAL | OPR | CRI | DOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCBDs | 1 | |||||||||

| LDR | 0.234 | 1 | ||||||||

| SLR | 0.148 | 0.196 | 1 | |||||||

| ROA | 0.316 | 0.391 | 0.394 | 1 | ||||||

| ROE | 0.218 | 0.321 | 0.348 | 0.553 | 1 | |||||

| SIZE | 0.387 | 0.490 | 0.475 | 0.374 | 0.379 | 1 | ||||

| SAL | 0.437 | 0.470 | 0.298 | 0.184 | 0.127 | 0.142 | 1 | |||

| OPR | 0.399 | 0.135 | 0.396 | 0.157 | 0.151 | 0.358 | 0.484 | 1 | ||

| CRI | 0.155 | 0.184 | 0.464 | 0.194 | 0.104 | 0.430 | 0.185 | 0.351 | 1 | |

| DOF | 0.468 | 0.371 | 0.296 | 0.193 | 0.346 | 0.397 | 0.175 | 0.478 | 0.358 | 1 |

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| SCBDs | 0.43 | 2.325 |

| LDR | 0.51 | 1.960 |

| SLR | 0.54 | 1.851 |

| SIZE | 0.57 | 1.754 |

| SAL | 0.58 | 1.724 |

| OPR | 0.63 | 1.587 |

| CRI | 0.68 | 1.470 |

| DOF | 0.71 | 1.408 |

| Mean VIF | 4.65 |

| LDR | SLR | ROA | ROE | SIZE | SAL | OPR | CRI | DOF | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-sectional independence | 0.510 | 0.521 | 0.475 | 0.432 | 0.765 | 0.548 | 0.418 | 0.308 | 0.284 |

| Off-diagonal elements | 0.414 | 0.267 | 0.412 | 0.386 | 0.365 | 0.484 | 0.358 | 0.219 | 0.135 |

| LDR | SLR | ROA | ROE | SIZE | SAL | OPR | CRI | DOF | |

| Cross-sectional independence | 1.348 | 0.947 | 0.748 | 0.894 | 0.565 | 0.474 | 0.658 | 1.107 | 0.660 |

| Off-diagonal elements | 0.928 | 0.732 | 0.713 | 0.735 | 0.294 | 0.198 | 0.389 | 0.105 | 0.448 |

| Model | Statistics | Coefficients | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| LDR | Slope | 0.638 | 0.613 |

| Adjusted slope | 0.729 | 0.702 | |

| SLR | Slope | 0.740 | 0.711 |

| Adjusted slope | 0.734 | 0.690 | |

| ROA | Slope | 0.803 | 0.781 |

| Adjusted slope | 0.811 | 0.784 | |

| ROE | Slope | 0.729 | 0.698 |

| Adjusted slope | 0.719 | 0.706 |

| [ROA] | [ROE] | [LDR] | [SLR] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) | Model (8) | Model (9) | Model (10) | |

| Lagged of dependent variables | 0.008 *** (2.53) | 0.012 *** (1.74) | 0.022 *** (1.35) | 0.019 *** (2.85) | 0.031 *** (3.16) | 0.006 *** (2.36) | 0.008 *** (2.09) | 0.011 *** (1.68) | 0.017 *** (2.74) | 0.021 *** (3.38) |

| LDR | 0.015 *** (2.10) | 0.023 ** (2.24) | 0.009 *** (1.34) | 0.017 ** (1.32) | ||||||

| SLR | 0.016 *** (2.18) | 0.015 ** (1.15) | ||||||||

| ROA | 0.018 *** (3.14) | 0.022 ** (2.44) | 0.027 *** (3.76) | |||||||

| ROE | 0.032 ** (3.77) | 0.012 *** (3.80) | 0.020 *** (2.64) | |||||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||

| SIZE | 0.022 *** (3.32) | 0.027 *** (3.65) | 0.026 ** (3.57) | 0.031 *** (4.01) | 0.018 *** (3.57) | 0.016 *** (3.43) | 0.018 *** (3.54) | 0.023 ** (3.25) | 0.021 *** (4.25) | 0.028 *** (3.47) |

| SALE | 0.018 *** (2.68) | 0.026 *** (3.38) | 0.038 ** (4.61) | 0.013 *** (1.86) | 0.012 *** (1.77) | 0.027 *** (3.94) | 0.031 *** (3.87) | 0.029 ** (3.52) | 0.024 *** (2.47) | 0.032 *** (3.68) |

| OPR | 0.042 * (5.55) | 0.047 * (6.06) | 0.052 * (6.28) | 0.042 ** (4.90) | 0.037 * (3.81) | 0.038 * (3.64) | 0.034 * (4.73) | 0.019 * (2.54) | 0.024 ** (2.52) | 0.014 * (2.45) |

| CRI | 0.047 *** (4.95) | 0.044 ** (5.52) | 0.015 ** (2.16) | 0.024 * (3.46) | 0.017 ** (1.40) | 0.058 *** (5.90) | 0.042 ** (4.16) | 0.056 ** (5.18) | 0.042 * (4.91) | 0.039 ** (5.22) |

| DOF | 0.010 *** (1.21) | 0.015 ** (2.47) | 0.005 ** (1.18) | 0.010 * (1.12) | 0.003 ** (1.18) | 0.009 *** (1.06) | 0.014 ** (1.85) | 0.010 ** (1.65) | 0.018 * (2.74) | 0.022 ** (2.30) |

| Yearly effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.3274 | 0.2484 | 0.1983 | 0.1148 | 0.3145 | 0.2046 | 0.2976 | 0.2474 | 0.2251 | 0.2854 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.3184 | 0.4375 | 0.4723 | 0.3412 | 0.2142 | 0.4872 | 0.5981 | 0.4023 | 0.2871 | 0.3174 |

| [TQ] | [TQ] | [CAR] | [CAR] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | Model (5) | Model (6) | Model (7) | Model (8) | Model (9) | Model (10) | |

| Lagged of dependent variables | 0.010 *** (2.80) | 0.011 *** (1.82) | 0.016 *** (2.41) | 0.018 *** (2.95) | 0.022 *** (2.66) | 0.013 *** (2.34) | 0.015 *** (2.50) | 0.008 *** (1.61) | 0.011 *** (1.55) | 0.020 *** (3.01) |

| CAR | 0.014 *** (1.90) | 0.032 ** (4.02) | 0.019 *** (2.64) | 0.031 *** (3.72) | 0.018 *** (2.77) | |||||

| TQ | 0.018 *** (2.32) | 0.007 ** (1.12) | 0.016 *** (1.84) | 0.019 *** (2.62) | 0.022 *** (3.97) | |||||

| Control variables | ||||||||||

| SIZE | 0.020 *** (2.42) | 0.021 *** (3.23) | 0.025 ** (3.47) | 0.032 *** (4.31) | 0.028 *** (3.84) | 0.015 *** (2.45) | 0.023 *** (3.53) | 0.026 ** (3.87) | 0.024 *** (3.22) | 0.025 *** (3.24) |

| SALE | 0.028 *** (2.75) | 0.036 *** (3.92) | 0.018 ** (2.24) | 0.023 *** (2.56) | 0.002 *** (0.87) | 0.020 *** (3.45) | 0.031 *** (4.22) | 0.028 ** (3.09) | 0.029 *** (3.56) | 0.035 *** (1.27) |

| OPR | 0.032 * (2.61) | 0.037 * (3.96) | 0.042 ** (4.37) | 0.032 ** (3.89) | 0.027 * (2.70) | 0.021 ** (2.72) | 0.016 * (2.55) | 0.022 *** (2.99) | 0.041 ** (5.39) | 0.037 ** (4.70) |

| CRI | 0.037 *** (3.51) | 0.034 ** (4.41) | 0.025 ** (3.22) | 0.020 * (2.47) | 0.027 ** (2.60) | 0.035 *** (3.82) | 0.039 ** (3.21) | 0.024 ** (3.18) | 0.023 * (2.11) | 0.013 ** (1.90) |

| DOF | 0.011 *** (1.95) | 0.016 ** (2.87) | 0.008 ** (2.53) | 0.012 * (1.40) | 0.008 ** (1.01) | 0.017 *** (2.16) | 0.009 ** (1.44) | 0.014 ** (2.24) | 0.021 * (2.10) | 0.006 ** (1.11) |

| Yearly effect | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Industry | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| R2 | 0.5787 | 0.3879 | 0.4076 | 0.3917 | 0.4273 | 0.2046 | 0.2976 | 0.2474 | 0.2251 | 0.2854 |

| Adjusted R2 | 0.4450 | 0.4878 | 0.5238 | 0.5813 | 0.5523 | 0.4872 | 0.5981 | 0.4023 | 0.2871 | 0.3174 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Darmansyah, A.; Ali, Q.; Parveen, S. Sophisticated Capital Budgeting Decisions for Financial Performance and Risk Management—A Tale of Two Business Entities. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060297

Darmansyah A, Ali Q, Parveen S. Sophisticated Capital Budgeting Decisions for Financial Performance and Risk Management—A Tale of Two Business Entities. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(6):297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060297

Chicago/Turabian StyleDarmansyah, Asep, Qaisar Ali, and Shazia Parveen. 2025. "Sophisticated Capital Budgeting Decisions for Financial Performance and Risk Management—A Tale of Two Business Entities" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 6: 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060297

APA StyleDarmansyah, A., Ali, Q., & Parveen, S. (2025). Sophisticated Capital Budgeting Decisions for Financial Performance and Risk Management—A Tale of Two Business Entities. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(6), 297. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18060297