Assessing the Relative Financial Literacy Levels of Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Preliminary Evidence from 13 Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. The OECD/INFE (2020) Methodology

3.1. The Questionnaire

- Screening (QC1–QC5 questions)

- Characteristics of the business (QC6–QC10 questions)

- Financial products (QP questions)

- Managing and planning business finances (QM questions)

- Financial knowledge and attitudes (QK questions)

- Financial education and protection (QF questions)

- Demographics (QD questions)

- Impact of COVID-19 (QX questions)

3.2. The Overall Financial Literacy Score

3.3. Data Collection Methodology and the Dataset

4. Study Methodology

5. Results

5.1. Overall Financial Literacy Score Results

5.2. Results per Aspect of Financial Literacy

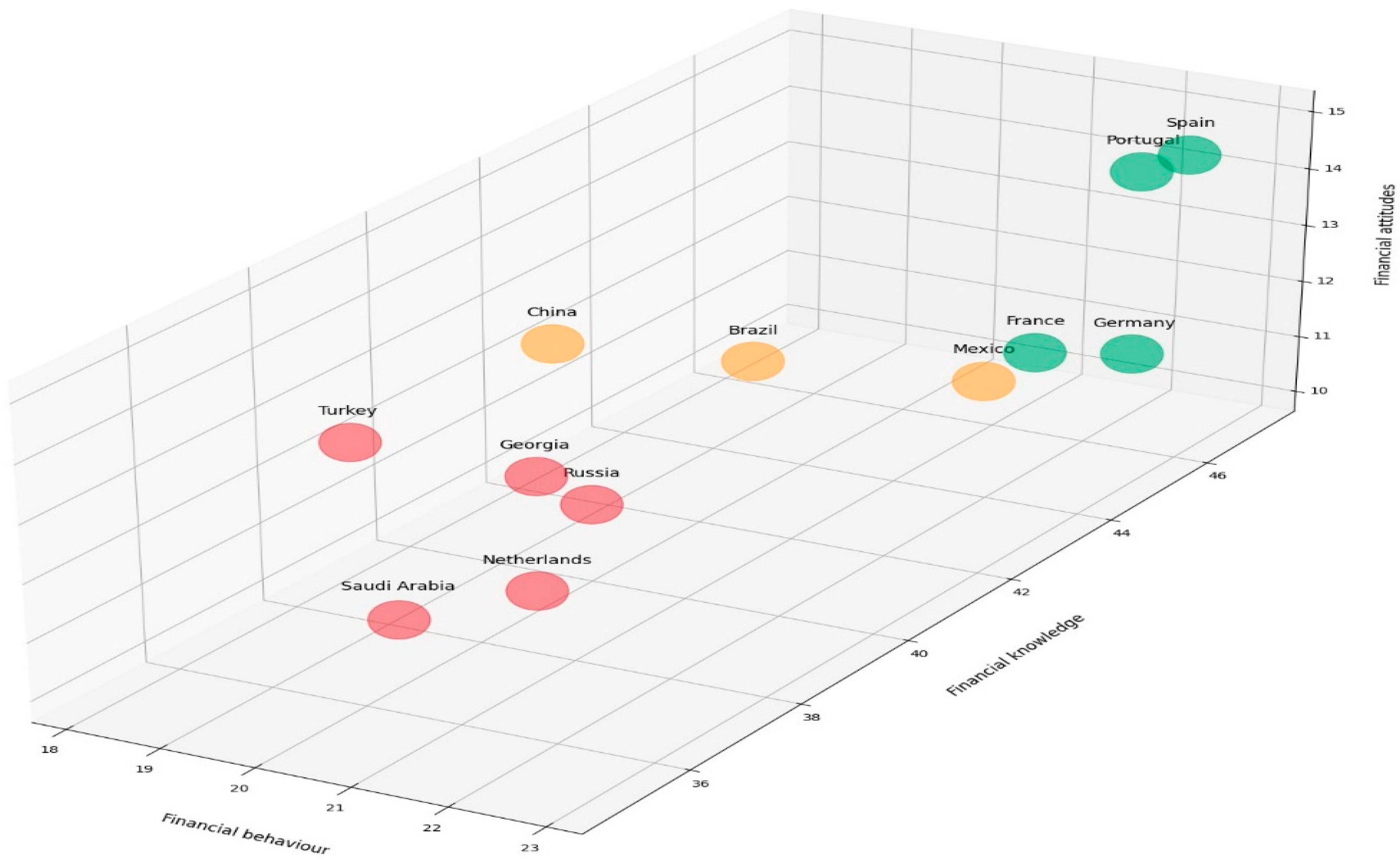

5.2.1. Overall Results

5.2.2. Financial Knowledge Results

5.2.3. Financial Behaviour Results

5.2.4. Financial Attitudes Results

5.2.5. Relating Findings to Existing Literature

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Question Number | Question: I Would Like to Know Whether You Think the Following Statements Are True or False: |

| QK7_1 | Dividends are part of what a business pays to a bank to repay a loan Record responses as: 1 = True, 0 = False, −97 = Don’t know, −99 = Refused 1 for correct response [false]. 0 in all other cases |

| QK7_2 | When a company obtains equity from an investor, it gives the investor part of the ownership of the company Record responses as: 1 = True, 0 = False, −97 = Don’t know, −99 = Refused 1 for correct response [tru3]. 0 in all other cases |

| QK7_3 | If a financial investment offers the chance to make a lot of money, it is likely that there is also a chance to lose a lot of money Record responses as: 1 = True, 0 = False, −97=Don’t know, −99 = Refused 1 for correct response [true]. 0 in all other cases |

| QK7_4 | High inflation means that the cost of living is increasing rapidly (1 for correct response [true]. 0 in all other cases) |

| QK7_5 | A 15-year loan typically requires higher monthly payments than a 30-year loan, but the total interest paid over the life of the loan will be less Record responses as: 1 = True, 0 = False, −97 = Don’t know, −99 = Refused (1 for correct response [true]. 0 in all other cases) |

| Question Number | Question |

| QP2 | Separation account: You mentioned that you have a current or savings account for your business. Can you tell me which of these statements best represents your situation?

|

| QP5 | Shopping around: Which of the following statements best describes how you made your most recent choice about a financial product or service for the business?

|

| QM3 | Keeping track of financial records How do you keep track of the financial records of the business?

|

| QM4 | Thought about retirement Have you thought about how you will fund your own retirement or maintain yourself when you will no longer work due to old age?

|

| QM6 | Strategies to cope with theft Imagine that tomorrow you discover that most of the equipment that you need to operate the business has been stolen (it could be computers, vehicles or other equipment). Which one of these statements best represents what you would do?

|

| QM7 | Thinking about your business, would you agree or disagree with the following statements?

|

| Question Number | Question: Still Thinking About Your Business… Would You Agree or Disagree with the Following Statements? |

| QK2_1 | I set long term financial goals for the business and strive to achieve them. Record responses as: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree; −97 = Don’t know, or −99 = Refuse 1 for long-term attitude [3 or 4]. 0 in all other cases. |

| QK2_2 | I am confident to approach banks and external investors to obtain business finance. Record responses as: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree; −97 = Don’t know, or −99 = Refuse 1 for long-term attitude [3 or 4]. 0 in all other cases. |

| QK2_4 | I prefer to follow my instinct rather than to make detailed financial plans for my business. Record responses as: 1 = strongly disagree; 2 = disagree; 3 = agree; 4 = strongly agree; −97 = Don’t know, or −99 = Refuse 1 for prudent attitude [1 or 2]. 0 in all other cases. |

| 1 | For more information on OECD/INFE, please see: https://www.oecd.org/en/networks/infe.html (accessed on 4 April 2024). |

| 2 | The 14th country that is not included in our study is Peru, as the scores that appear in the database seem problematic. In addition, the OECD/INFE reports for Italy only provide scores for micro-enterprises (1–9 employees). |

| 3 | The dataset is available here: https://web-archive.oecd.org/2021-11-12/616062-G20-OECD-INFE-report-navigating-the-storm-tables-figures.xlsx (accessed on 20 April 2024). |

| 4 | Only questions and results are shown with no indicative answers to avoid excess table sizes. For the full questions, including indicative answers, please refer to Appendix A. |

| 5 | Same as in note 4. |

References

- Abdallah, A., Harraf, A., Ghura, H., & Abrar, M. (2024). Financial literacy and small and medium enterprises performance: The moderating role of financial access. Journal of Financial Reporting and Accounting. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwala, S. K., Barua, S. K., Jacob, J., & Varma, J. R. (2013). Financial literacy among working young in urban India. Indian Institute of Management. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad, K. (2024). The influence of financial literacy, risk orientation and qualified accountants on performance in micro, small and medium enterprises: The mediating role of management accounting. International Review of Management and Marketing, 14(6), 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andreou, P., & Philip, D. (2018). Financial knowledge among university students and implications for personal debt and fraudulent investments. Cyprus Economic Policy Review, 12(2), 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anshika, A., & Singla, A. (2022). Financial literacy of entrepreneurs: A systematic review. Managerial Finance, 48(9/10), 1352–1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atkinson, A. (2017). Financial education for MSMEs and potential entrepreneurs (Working Papers Finance No. 43). Insurance and Private Pensions. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Balloch, A., Nicolae, A., & Philip, D. (2015). Stock market literacy, trust and participation. Review of Finance, 19(5), 1925–1963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuyan, U. (2016). A study on the performance of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in India. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 16(9), 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. Y., Jackson, H. E., Madrian, B. C., & Tufano, P. (2011). Consumer financial protection. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 25(1), 91–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chimucheka, T., & Rungani, E. (2011). The impact of inaccessibility to bank finance and lack of financial management knowledge to small, medium and micro enterprises in Buffalo City municipality, South Africa. African Journal of Business Management, 5(14), 5509–5517. [Google Scholar]

- Culebro-Martínez, R., Moreno-García, E., & Hernández-Mejía, S. (2024). Financial literacy of entrepreneurs and companies’ performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(2), 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bassa Scheresberg, C. (2013). Financial literacy and financial behavior among young adults: Evi dence and implications. Numeracy, 6(2), 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deevy, M., Lucich, S., & Beals, M. (2012). Scams, schemes and swindles: A review of consumer financial fraud research. Stanford University Center on Longevity Financial Fraud Research Center. [Google Scholar]

- Deuflhard, F., Georgarakos, D., & Inderst, R. (2019). Financial literacy and savings account returns. Journal of the European Economic Association, 17(2), 131–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwyanti, A. (2024). The importance of financial literacy in financial management in Micro, Small and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). Journal of Applied Management and Business, 5(1), 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EC. (2021). Annual report on European SMEs. Available online: https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/849659ce-dadf-11eb-895a-01aa75ed71a1 (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Engström, P., & McKelvie, A. (2017). Financial literacy, role models, and micro-enterprise performance in the informal economy. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 35(7), 855–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferawati, D., Fadah, I., & Paramu, H. (2024). Literature review: Financial literacy in the context of micro enterprise development and the methods used. Jurnal Pendidikan Akuntansi dan Keuangan, 12(2), 189–202. [Google Scholar]

- Gbandi, E. C., & Amissah, G. (2014). Financing options for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) in Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 10(1), 327–340. [Google Scholar]

- Graha, A., Asna, A., & Suharso, A. (2024). Crafting the msmes’ performance into financial literacy, financial inclusion, and fintech in emerging countries. Migration Letters, 21(8), 50–63. [Google Scholar]

- Graña-Alvarez, R., Lopez-Valeiras, E., Loureiro, M. G., & Coronado, F. (2022). Financial literacy in SMEs: A systematic literature review and a framework for further inquiry. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(1), 331–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamid, A., Widjaja, W., Sutrisno, S., Napu, F., & Sipajung, B. (2024). The role of fintech on enhancing financial literacy and inclusive financial Management in MSMEs. TECHNOVATE: Journal of Information Technology and Strategic Innovation Management, 1(2), 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S., Sureka, R., & Colombage, S. (2020). Capital structure of SMEs: A systematic literature review and bibliometric analysis. Management Review Quarterly, 70, 535–565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2007). Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: Evidence and implications for financial education. Business Economics, 42(1), 35–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A., & Mitchell, O. (2014). The economic importance of financial literacy: Theory and evidence. Journal of Economic Literature, 52(1), 5–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lusardi, A., & Tufano, P. (2015). Debt literacy, financial experiences, and overindebtedness. Journal of Pension Economics & Finance, 14(4), 332–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murdiono, A., Zen, F., & Istanti, L. (2024). The influence of financial technology on the performance of MSMEs in the regency blitar: Effect financial literacy mediation. Journal of International Accounting Taxation and Information Systems, 1(3), 150–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkundabanyanga, S. K., Kasozi, D., Nalukenge, I., & Tauringana, V. (2014). Lending terms, financial literacy and formal credit accessibility. International Journal of Social Economics, 41(5), 342–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyamboga, T. O., Nyamweya, B. O., & Njeru, F. (2014). An assessment of the effect of financial literacy on loan repayment by small and medium entrepreneurs in Ngara, Nairobi county. Research Journal of Finance and Accounting, 5(12), 181–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD/INFE. (2020). OECD/INFE survey instrument to measure the financial literacy of MSMEs. Available online: https://www.bancaditalia.it/statistiche/tematiche/indagini-famiglie-imprese/alfabetizzazione-imprese/Data-Description.pdf (accessed on 10 May 2024).

- OECD/INFE. (2021). G20/OECD-INFE report on navigating the storm: MSMEs’ financial and digital competencies in COVID-19 times. OECD Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Psillaki, M., & Daskalakis, N. (2009). Are the determinants of capital structure country or firm specific? Small Business Economics, 33, 319–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramalho, J., & Silva, V. (2009). A two-part fractional regression model for the capital structure decisions of micro, small, medium and large firms. Quantitative Finance, 9(5), 621–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, A., Sami Latif, A., & Hassan, S. (2025). The role of financial literacy in entrepreneurial success: A study of small businesses in Pakistan. Qualitative Research Review Letter, 3(1), 192–216. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. (2024). 2024 Theme: MSMEs and the SDGs. Available online: https://www.un.org/en/observances/micro-small-medium-businesses-day (accessed on 16 April 2025).

- Urefe, O., Odonkor, T. N., Chiekezie, N. R., & Agu, E. E. (2024). Enhancing small business success through financial literacy and education. Magna Scientia Advanced Research and Reviews, 11(2), 297–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Rooij, M., Lusardi, A., & Alessie, R. (2012). Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. Economic Journal, 122(560), 449–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wachira, M. I., & Kihiu, E. N. (2012). Impact of financial literacy on access to financial services in Kenya. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 3(19), 40–50. [Google Scholar]

- World Bank. (2021). Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) finance (IBRD-IDA). Available online: https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/smefinance (accessed on 14 April 2024).

- Zaimovic, A., Omanovic, A., Dedovic, L., & Zaimovic, T. (2025). The effect of business experience on fintech behavioural adoption among MSME managers: The mediating role of digital financial literacy and its components. Future Business Journal, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Country | Sample Size | Timing of Data Collection | Method of Data Collection |

|---|---|---|---|

| Brazil | 1011 | 26 May to 21 June 2021 | Telephone survey (CATI) |

| China | 2500 | 2 April to 11 May 2021 | Mixed methods |

| France | 1002 | 31 March to 21 April 2021 | Telephone survey |

| Georgia | 1002 | 26 June to 18 July 2021 | Telephone and Face-to-face survey |

| Germany | 2366 | 10 to 26 March 2021 | Online survey |

| Italy | 2076 | March to May 2021 | Almost all respondents (99 per cent) used a dedicated online platform. Other respondents chose to fill out a (faxed) paper format of the questionnaire |

| Mexico | 753 | 2 August to 10 September 2021 | Telephone survey |

| Netherlands | 1151 | 9 May to 4 June 2021 | Online survey (CAWI) |

| Peru | 600 | 19 May to 30 August 2021 | Mixed methods, mainly through telephone, virtual or in-person |

| Portugal | 1541 | 13 July to 1 August 2021 | Online survey |

| Russia | 1023 | 6 to 21 July 2021 | Mix methods: telephone and online survey (CATI + CAWI) |

| Saudi Arabia | 1094 | 21 April to 23 June 2021 | Face-to-face survey |

| Spain | 1120 | 22 March to 21 May 2021 | Online survey |

| Turkey | 1050 | 16 April to 17 May 202 | Mixed methods: face-to-face, telephone and online survey (CAPI, CATI and Online) |

| Financial Literacy Scores (Out of 100) | Percentage of Business Owners Reaching a High Score in Financial Literacy (>80) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Knowledge | Financial Behaviour | Financial Attitudes | Financial Literacy Overall Score | ||

| Score | Score | Score | Score | % | |

| Brazil | 20 | 39 | 10 | 69 | 25 |

| China | 17 | 38 | 11 | 66 | 32 |

| France | 22 | 37 | 10 | 69 | 26 |

| Georgia | 18 | 32 | 9 | 59 | 8 |

| Germany | 22 | 38 | 9 | 69 | 28 |

| Italy | 21 | 41 | 11 | 73 | 43 |

| Mexico | 20 | 34 | 10 | 64 | 17 |

| Netherlands | 21 | 36 | 8 | 64 | 20 |

| Portugal | 22 | 43 | 13 | 77 | 54 |

| Russia | 19 | 37 | 9 | 65 | 20 |

| Saudi Arabia | 20 | 36 | 12 | 67 | 20 |

| Spain | 22 | 42 | 12 | 76 | 54 |

| Turkey | 18 | 38 | 13 | 69 | 30 |

| Overall average | 20 | 38 | 11 | 68 | 29 |

| Overall standard deviation | 1.77 | 3.13 | 1.59 | 5.05 | 13.83 |

| Financial Literacy Scores (Out of 100) | Percentage of Business Owners Reaching a High Score in Financial Literacy (>80) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Financial Knowledge | Financial Behaviour | Financial Attitudes | Financial Literacy Overall Score | ||

| Score | Score | Score | Score | % | |

| Brazil | 20 | 43 | 12 | 76 | 45 |

| China | 19 | 41 | 13 | 72 | 45 |

| France | 23 | 43 | 13 | 79 | 52 |

| Georgia | 20 | 39 | 12 | 71 | 29 |

| Germany | 23 | 45 | 12 | 80 | 61 |

| Mexico | 23 | 42 | 13 | 78 | 49 |

| Netherlands | 20 | 39 | 10 | 69 | 38 |

| Portugal | 22 | 47 | 14 | 84 | 69 |

| Russia | 20 | 40 | 11 | 71 | 31 |

| Saudi Arabia | 21 | 35 | 12 | 68 | 21 |

| Spain | 23 | 46 | 15 | 84 | 72 |

| Turkey | 18 | 39 | 12 | 68 | 26 |

| Overall average | 21 | 42 | 12 | 75 | 45 |

| Overall standard deviation | 1.85 | 3.55 | 1.37 | 5.95 | 16.68 |

| Financial Knowledge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Correctly Answering Questions About the Following Statements: | ||||||

| Dividends Are Part of What a Business Pays to a Bank to Repay a Loan (False) | When a Company Obtains Equity From an Investor It Gives the Investor Part of the Ownership of the Company (True) | If a Financial Investment Offers the Chance to Make a lot of Money It Is Likely That There Is Also a Chance to Lose a Lot of Money (True) | High Inflation Means That the Cost of Living Is Increasing Rapidly (True) | A 15-Year Loan Typically Requires Higher Monthly Payments Than a 30-Year Loan of the Same Amount, But the Total Interest Paid Over the Life of the Loan Will Be Less (True) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 44.6 | 54.3 | 91.3 | 90.7 | 52.0 | |

| China | 72.4 | 36.1 | 68.3 | 55.0 | 58.6 | |

| France | 82.6 | 47.2 | 85.4 | 87.7 | 68.4 | |

| Georgia | 32.1 | 61.3 | 74.2 | 70.4 | 61.9 | |

| Germany | 86.5 | 41.9 | 92.6 | 91.5 | 66.8 | |

| Italy | 83.1 | 45.3 | 82.7 | 80.4 | 59.3 | |

| Mexico | 45.8 | 76.4 | 88.9 | 82.0 | 50.4 | |

| Netherlands | 72.1 | 45.7 | 86.0 | 92.0 | 59.3 | |

| Portugal | 72.4 | 60.9 | 73.5 | 85.7 | 74.2 | |

| Russia | 73.9 | 49.8 | 68.5 | 72.2 | 57.0 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 46.6 | 75.7 | 77.9 | 74.3 | 68.6 | |

| Spain | 88.1 | 51.7 | 82.2 | 81.5 | 77.4 | |

| Turkey | 32.7 | 55.1 | 75.8 | 74.0 | 68.5 | |

| Overall average | 64.1 | 54.0 | 80.6 | 79.8 | 63.2 | 68.3 |

| Overall standard deviation | 20.63 | 12.10 | 8.20 | 10.55 | 8.17 | 11.9 |

| Financial Behaviour Score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Indicating the Following Savvy Financial Behaviours: | ||||||||||

| Separation Account | Shopping Around | Keeping Track of Financial Records | Thought About Retirement | Strategies to Cope with Theft | I Keep Secure Data and Information About the Business | I Compare the Cost of Different Sources of Finance for the Business | I Forecast the Profitability of the Business Regularly | I Adjust My Planning According to the Changes in Economic Factors | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 63.3 | 42.1 | 96.7 | 70.5 | 53.1 | 91.9 | 78.9 | 83.8 | 85.3 | |

| China | 50.8 | 65.5 | 89.3 | 62.1 | 52.3 | 78.3 | 82.0 | 83.8 | 79.0 | |

| France | 87.5 | 35.1 | 97.4 | 72.8 | 78.9 | 80.0 | 56.5 | 58.8 | 65.1 | |

| Georgia | 32.0 | 32.9 | 90.5 | 50.8 | 18.3 | 79.3 | 75.2 | 78.2 | 86.0 | |

| Germany | 74.0 | 35.0 | 91.6 | 93.3 | 68.1 | 94.0 | 57.5 | 65.6 | 66.0 | |

| Italy | 87.6 | 58.3 | 96.5 | 47.8 | 62.1 | 90.9 | 82.1 | 85.6 | 86.5 | |

| Mexico | 31.6 | 30.0 | 93.9 | 56.5 | 21.4 | 90.5 | 75.1 | 80.7 | 89.9 | |

| Netherlands | 75.5 | 26.7 | 94.9 | 80.2 | 75.0 | 90.9 | 52.1 | 53.1 | 63.4 | |

| Portugal | 92.4 | 53.1 | 97.5 | 72.5 | 73.3 | 95.5 | 80.9 | 81.3 | 87.8 | |

| Russia | 62.9 | 52.4 | 93.3 | 59.0 | 36.2 | 84.6 | 80.5 | 77.6 | 80.8 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 58.6 | 48.8 | 81.1 | 40.6 | 41.7 | 89.9 | 84.8 | 79.1 | 80.7 | |

| Spain | 92.4 | 63.8 | 97.9 | 55.4 | 70.3 | 94.2 | 79.7 | 76.8 | 75.4 | |

| Turkey | 49.5 | 51.3 | 96.6 | 57.9 | 63.6 | 85.3 | 79.3 | 84.1 | 84.7 | |

| Overall average | 66.0 | 45.8 | 93.6 | 63.0 | 54.9 | 88.1 | 74.2 | 76.0 | 79.3 | 71.2 |

| Overal standard deviation | 21.19 | 12.99 | 4.70 | 14.36 | 20.11 | 5.95 | 11.11 | 10.30 | 9.12 | 12.2 |

| Financial Attitudes Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Indicating the Following Savvy Financial Attitudes: | ||||

| I Set Long-Term Financial Goals for the Business and Strive to Achieve Them (Agree) | I Am Confident to Approach Banks and External Investors to Obtain Business Finance (Agree) | I Prefer to Follow My Instinct Rather Than Make Detailed Financial Plans for My Business (Disagree) | ||

| % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 79.8 | 50.5 | 42.1 | |

| China | 70.2 | 67.0 | 53.2 | |

| France | 60.4 | 69.9 | 39.4 | |

| Georgia | 69.4 | 57.4 | 26.1 | |

| Germany | 69.3 | 25.3 | 54.2 | |

| Italy | 78.7 | 59.3 | 51.8 | |

| Mexico | 81.1 | 45.5 | 48.8 | |

| Netherlands | 65.1 | 29.8 | 34.0 | |

| Portugal | 88.7 | 64.1 | 60.1 | |

| Russia | 72.1 | 43.9 | 41.9 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 93.4 | 83.7 | 22.0 | |

| Spain | 76.7 | 68.3 | 61.0 | |

| Turkey | 81.0 | 79.3 | 57.5 | |

| Overall average | 75.8 | 57.2 | 45.5 | 59.5 |

| Overal standard deviation | 9.29 | 17.67 | 12.61 | 13.2 |

| Financial Knowledge | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Correctly Answering Questions About the Following Statements: | ||||||

| Dividends Are Part of What a Business Pays to a Bank to Repay a Loan (False) | When a Company Obtains Equity From an Investor, It Gives the Investor Part of the Ownership of the Company (True) | If a Financial Investment Offers the Chance to Make a Lot of Money, It Is Likely That There Is also a Chance to Lose a Lot of Money (True) | High Inflation Means That the Cost of Living Is Increasing Rapidly (True) | A 15-Year Loan Typically Requires Higher Monthly Payments Than a 30-Year Loan of the Same Amount, but the Total Interest Paid over the Life of the Loan Will Be Less (True) | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 63.8 | 56.2 | 88.5 | 86.4 | 51.7 | |

| China | 72.4 | 42.0 | 74.9 | 62.8 | 64.5 | |

| France | 88.3 | 52.4 | 85.3 | 89.3 | 67.3 | |

| Georgia | 48.3 | 64.0 | 82.0 | 76.4 | 64.0 | |

| Germany | 90.3 | 40.2 | 90.7 | 90.7 | 72.2 | |

| Mexico | 71.4 | 78.6 | 88.6 | 88.6 | 68.6 | |

| Netherlands | 74.6 | 53.0 | 75.9 | 76.1 | 60.1 | |

| Portugal | 76.0 | 64.6 | 78.5 | 83.7 | 75.1 | |

| Russia | 75.5 | 56.5 | 71.8 | 73.9 | 59.4 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 52.4 | 82.2 | 79.1 | 80.3 | 65.7 | |

| Spain | 86.1 | 55.2 | 84.2 | 86.3 | 78.5 | |

| Turkey | 31.6 | 52.0 | 67.6 | 77.7 | 68.7 | |

| Overall average | 69.2 | 58.1 | 80.6 | 81.0 | 66.3 | 71.0 |

| Overal standard deviation | 17.55 | 12.67 | 7.22 | 8.11 | 7.26 | 10.6 |

| Financial Behaviour Score | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Indicating the Following Savvy Financial Behaviours: | ||||||||||

| Separation Account | Shopping Around | Keeping Track of Financial Records | Thought About Retirement | Strategies to Cope with Theft | I Keep Secure Data and Information About the Business | I Compare the Cost of Different Sources of Finance for the Business | I Forecast the Profitability of the Business Regularly | I Adjust My Planning According to the Changes in Economic Factors | ||

| % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 81.2 | 60.6 | 100.0 | 75.9 | 68.7 | 92.1 | 87.9 | 85.4 | 85.9 | |

| China | 62.3 | 71.0 | 92.0 | 65.0 | 63.9 | 83.4 | 87.3 | 87.0 | 83.1 | |

| France | 92.2 | 52.4 | 99.6 | 72.6 | 86.5 | 90.3 | 77.9 | 83.4 | 83.8 | |

| Georgia | 65.2 | 49.4 | 100.0 | 57.3 | 39.3 | 85.4 | 83.1 | 93.3 | 91.0 | |

| Germany | 94.1 | 53.5 | 95.0 | 94.8 | 83.8 | 96.0 | 74.3 | 86.3 | 82.5 | |

| Mexico | 72.9 | 47.1 | 98.6 | 72.9 | 54.3 | 97.1 | 84.3 | 90.0 | 91.4 | |

| Netherlands | 65.2 | 45.7 | 91.4 | 67.9 | 78.0 | 88.5 | 67.5 | 78.4 | 74.9 | |

| Portugal | 96.6 | 76.0 | 98.2 | 75.1 | 85.2 | 97.8 | 93.8 | 89.8 | 93.2 | |

| Russia | 70.5 | 62.1 | 95.3 | 63.8 | 49.1 | 88.3 | 85.6 | 83.6 | 88.5 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 53.5 | 47.9 | 79.6 | 31.2 | 41.2 | 94.1 | 88.6 | 77.2 | 82.5 | |

| Spain | 97.9 | 84.2 | 100.0 | 54.2 | 85.2 | 93.6 | 90.7 | 90.3 | 89.1 | |

| Turkey | 42.2 | 51.5 | 96.0 | 66.6 | 70.6 | 85.7 | 82.2 | 83.3 | 82.2 | |

| Overall average | 74.5 | 58.4 | 95.5 | 66.4 | 67.1 | 91.0 | 83.6 | 85.7 | 85.7 | 78.7 |

| Overal standard deviation | 18.11 | 12.57 | 5.85 | 15.16 | 17.54 | 4.86 | 7.36 | 4.84 | 5.18 | 10.2 |

| Financial Attitudes Score | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percentage of Business Owners Indicating the Following Savvy Financial Attitudes: | ||||

| I Set Long-Term Financial Goals for the Business and Strive to Achieve Them (Agree) | I Am Confident to Approach Banks and External Investors to Obtain Business Finance (Agree) | I Prefer to Follow My Instinct Rather Than to Make Detailed Financial Plans for My Business (Disagree) | ||

| % | % | % | ||

| Brazil | 82.1 | 69.4 | 48.1 | |

| China | 79.0 | 75.3 | 60.4 | |

| France | 77.8 | 88.1 | 55.8 | |

| Georgia | 88.8 | 73.0 | 39.3 | |

| Germany | 82.7 | 57.2 | 71.5 | |

| Mexico | 90.0 | 71.4 | 58.6 | |

| Netherlands | 70.3 | 50.7 | 48.6 | |

| Portugal | 92.6 | 80.3 | 69.5 | |

| Russia | 81.6 | 55.4 | 54.4 | |

| Saudi Arabia | 94.2 | 82.2 | 20.3 | |

| Spain | 91.5 | 88.4 | 77.9 | |

| Turkey | 78.8 | 78.0 | 48.5 | |

| Overall average | 84.1 | 72.5 | 54.4 | 70.3 |

| Overal standard deviation | 7.27 | 12.45 | 15.46 | 11.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Daskalakis, N. Assessing the Relative Financial Literacy Levels of Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Preliminary Evidence from 13 Countries. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050283

Daskalakis N. Assessing the Relative Financial Literacy Levels of Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Preliminary Evidence from 13 Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050283

Chicago/Turabian StyleDaskalakis, Nikolaos. 2025. "Assessing the Relative Financial Literacy Levels of Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Preliminary Evidence from 13 Countries" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050283

APA StyleDaskalakis, N. (2025). Assessing the Relative Financial Literacy Levels of Micro and Small Entrepreneurs: Preliminary Evidence from 13 Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 283. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050283