1. Introduction

This paper was written in response to a

JRFM Special Issue call titled Sustainability Reporting and Corporate Governance. We research the contention that “the role of corporate governance in sustainability and how organizations contribute to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) has become a global priority” (

Pirzada & Moens, 2024). The combined impact of an increasing world population and climate change is stimulating action to enhance water supply resilience in many countries, consistent with the pursuit of UN SDG 6: “

ensure availability and sustainable management of water and sanitation for all” (e.g.,

Tzanakakis et al., 2020;

Douville et al., 2021). This requires the economically viable management of three classes of water resources: “blue” water, that is, freshwater found in natural waterways; “green” water embedded in the soil; and “grey” water, a form of polluted blue water. Grey water recycling is seen as particularly important in the pursuit of UN SDG 6 (e.g.,

Tortajada, 2020), with risks related to unregulated practices to be managed (e.g.,

Voulvoulis, 2018). The term “water governance” has been used to characterize actions needed to maintain a balance between these three classes of water and their consumption, with water scarcity being a dominant concern (

Woodhouse & Muller, 2017;

Falkenmark et al., 2019). Innovation on multiple fronts is needed: technological, social, and business model (e.g.,

Leboucher & Oberti, 2025).

The pursuit of water resilience brings together initiatives by different water sector actors in response to potential system stressors: flood, drought, pollution, and distribution infrastructure failures (e.g.,

Rodina & Chan, 2019). Drawing on an analysis of 222 water resilience publications,

Pamidimukkala et al. (

2021) identified 51 potential challenges they classified into five categories: environmental, technical and infrastructure, social, organizational, and financial and economic. Thus, action that makes business sense must also be seen to support stakeholder expectations and how this may be measured and reported requires careful consideration (e.g.,

Balaei et al., 2018). This action influences and is influenced by communication modalities, regulations and cultural norms, and access to resources, requiring contributions from business, community, and government actors (e.g.,

Caprar & Neville, 2012). It has been argued that the adoption of enterprise governance standards that embody transparency, participation, legality, rationality, proportionality, reviewability, and accountability facilitates dealing with this complex set of conditions (

McIntyre, 2018). We address a research gap to investigate how policy and practice are orchestrated, leading to our research question:

How might an enterprise support the pursuit of viable water resilience goals whilst engaging with a diverse group of stakeholders?Water conservation and recycling action plus associated energy usage initiatives are viewed through a circular economy lens. Governance action is seen as establishing rules and allocating resources to balance endogenous and exogenous dynamic complexities (

Ludwig & Sassen, 2022). We follow the lead of

Ahmed and Sundaram (

2007), who adopted a system dynamics modelling approach to consider the integration of sustainability practice and sustainability reporting in support of transparency.

This paper begins with a literature survey considering water resilience scenarios and circular economy perspectives as well as governance and integrated sustainability reporting requirements to identify emergent themes. This is followed by the representation of specific research gaps, proposition development, and the presentation of an agile structuration theoretical model that considers the dynamics involved, which is applied to an in-depth longitudinal case study of an innovative Australian water utility. A within-case causal tracing process is utilized to map the evolutionary dynamics of governance and reporting, viewing operations as embedded in a broader socio-economic ecosystem. It is observed that making business sense is facilitated by proactive governance, the monetization of all aspects of operations, and by transparent reporting arrangements that help maintain stakeholder trust.

2. Literature Review and Theoretical Background

Our objective in this section is to identify current and emergent concepts from the literature, building on comprehensive review articles by others and current research. There is a substantial body of literature associated with each of the technology and management themes explored in the following sub-sections. Large scale sustainability and governance studies have identified some variety in the specific theoretical foundations used (e.g., stakeholder theory, agency theory and socio-political theories—

Naciti et al. (

2022)). We contend that such foundations provide a partial view and introduce agile structuration theory, which combines structuration, agile project management, and business ecosystem theories.

2.1. Water Resilience Scenarios

Blackmore and Plant (

2008) drew on two metaphors in considering integrated urban water system options in a risk-based sustainability context. These were “the stability landscape” covering both routine and disruptive aspects, and the “adaptive cycle”, considering how to prepare for and recover from external forces of change. They noted the prospect of turning potential threats into opportunities to enhance overall system operations. For example, a study of resilience theory and its application by

Carlson et al. (

2012) considered operational resilience to be exemplified as: “

the ability of an entity (e.g.,

asset, organization, community, region) to anticipate, resist, absorb, respond to, adapt to, and recover from a disturbance”.—a risk management perspective.

Makropoulos et al. (

2018) proposed a water resilience assessment framework noting varying degrees of decision-maker influence: strong internal control, transactional interface control where the decision-maker may have some influence, and an external system where the decision-maker may have no control (e.g., in mandated reporting requirements). Their framework involved comparing a variety of increasingly more “stressful” scenarios.

Craig (

2020) noted that change should be the norm, suggesting a complex adaptive socio-ecological perspective where “once and done” planning and management would not be practical. Drawing on a combination of literature review, interviews, and case studies in four countries,

Johannessen and Wamsler (

2017) contend that it is necessary to discern between and manage three intervention levels (i.e., socio-economic, external hazard considerations, and larger social–ecological systems) to be sustainable. Drawing on a review of drinking water resilience, policy, and planning in 100 US cities,

Friedman et al. (

2024) proposed a transferable analysis framework that involved (a—planning for the future—an extended temporal scale; (b—planning at broad scales—an extended spatial scale; (c—buffering against change—accounting for social and environmental change; and (d—investing and engaging in community wellbeing—strengthening the social system.

We identified six recurring water resilience sub-themes in our broader literature search, as shown in

Table 1.

With respect to the recurring water resilience sub-themes, it is reasonable to conclude that the “stability landscape” stressors may be short-term (e.g., flash flooding) or long term (e.g., population growth or climate change). “Adaptation cycle” requirements may include redundancy in water collection and distribution arrangements, water recycling, and finding an economic balance via a portfolio of initiatives. However, implementation requires infrastructure and social change via the orchestration of the following key resources:

Timely action by motivated, knowledgeable actors within and external to a water management enterprise continuously adapting through feedback mechanisms to support “social learning” (e.g.,

Pahl-Wostl et al., 2008);

The establishment of economically viable integrated water management resource infrastructure and process that support both clean water availability and the water–energy–food nexus (e.g.,

Albrecht et al., 2021).

How this orchestration is achieved is viewed as a research gap, reflecting the observations of

Rodina (

2019) that more studies were needed into (a) practices integrating the contribution of various water subsectors and (b) the influence of institutional and governance factors.

2.2. Circular Economy

In a limited supply environment, water recycling becomes an important process, with potential complementary benefits and risks to be managed (e.g.,

Voulvoulis, 2018).

Radcliffe (

2022) provided a comprehensive review of water recycling in Australia noting the increasing use of water recycling practice and desalination technology, and that different regions had different needs at different times. They reiterated the need to gain public trust and confidence in the quality of recycled water via two-way engagement processes. The need to transition from a linear water usage model, characterized as extract, use dispose, to a circular economy water system, characterized by reuse of water within the technical water system, have been observed by many authors (e.g.,

Rickfält, 2019;

Mannina et al., 2021). This has led to a need for innovative water management practices across technological, regulatory, organizational, social, and economic dimensions.

Mannina et al. (

2021, p. 14) suggested that “the role of water-management utilities is crucial; indeed, they must change their traditional vision of a utility manager and transform into actors in the market for recovered resources”. Furthermore,

Sgroi et al. (

2018) observed that the characteristics of local water markets and economics may determine the feasibility of water re-use. Therefore, political and decisional, social and economic, and technological and environmental factors need to be considered.

2.2.1. Circular Economy Background Research

Circular economy research has suggested that learning through experimentation is an essential evolutionary process (e.g.,

Aminoff & Pihlajamaa, 2020) and that regulations and societal norms may have to adapt to the learning (e.g.,

Voulvoulis, 2018;

Ziegler, 2019). How this learning takes place is seen as a research gap.

It has also been noted there is an interplay between water, energy, and the conversion of waste into valuable products where a circular economy framework has five components: reduce (usage), remove (pollutants), re-use (non-potable water), recycling (recovery of wastewater) and recovery (of assets from water) (e.g.,

Smol et al., 2020). In addition, ongoing technological developments may provide new resources supporting continuous innovation (e.g.,

Liu et al., 2021;

Mannina et al., 2021). The emergence of “water 4.0” digital technology adoption as a collaborative industry imperative is changing both operational and business practices (

Alabi et al., 2019).

2.2.2. The Circular Economy as a Complex Adaptive System

The literature generally considers conditions supporting the evolution of a circular water economy with limited information about the dynamics involved. Multi-actor change on a number of fronts is needed.

Peltoniemi and Vuori (

2004) had suggested a multi-actor business ecosystem may be represented as a complex adaptive environment that develops through self-organization, emergence, and co-evolution in supporting adaptability. Circular economy initiatives are embedded in a broader business ecosystem that provides inputs and utilizes outputs. If appropriate input/output conditions are not met, then the initiative may not be economically viable.

Phillips and Ritala (

2019) studied business ecosystem attributes to suggest a research approach to their exploration.

Three focus areas were suggested:

A conceptual view: how we think about a particular instance—what is the focal issue and what are appropriate boundaries?

A structural view: what we know about the instance, its actors, and their relationships at a chosen level of analysis.

A temporal view: how an instance may change over time—its dynamics and internal/external co-evolution.

Our particular focus is on the conceptual view, focusing on how innovation supports freshwater access and wastewater recycling, where climate and geographical factors make the externalities place-dependent. Our level of analysis is an individual enterprise (boundary and structural view). We are drawing on a longitudinal study to consider the interaction between external change factors and internal responses (temporal view).

2.3. Enterprise Governance Considerations

Woodhouse and Muller (

2017) reviewed the emergence of a “water governance” concept where shared responsibilities extend across multiple jurisdictions associated with a particular water network and noted the dominance of a scarcity narrative. They also noted the need for multiple disciplines to be involved in associated Integrated Water Resource Management. Matters of equitable water allocations across a diverse range of users were raised in the context of finding a balance between the public nature of the resource and private rights to it. A recent study of water resilience policy development covering 100 US cities found that they were at different stages on maturity and noted the influence of community attributes on planning.

Ludwig and Sassen (

2022) researched enterprise governance mechanisms that may drive corporate sustainability. From a sample of 56 articles, they found some board attributes such as diversity, independence, size, and use of a sustainability committee, in addition to the role of the CEO, ownership concentration, and disclosure and transparency practices, all contributed to achieving integration.

McIntyre (

2018) considered matters of transnational environmental regulation and how firms were approaching environmental governance in this context. He noted the emergence of a set of practices that could be applied in a variety of contexts: “including transparency, participation, legality, rationality, proportionality, reviewability and accountability—which serve to enhance the credibility and legitimacy of each regulatory mechanism”. A review of 468 research studies relating to governance and sustainability by

Naciti et al. (

2022) identified three dominant themes, represented as corporate social responsibility and reporting, corporate governance strategies, and board composition. They noted that stakeholder theory, agency theory and socio-political theories were the most common study foundations.

Fisher et al. (

2006) introduced the idea of technology governance to integrate the work of scientist and engineers and others in reflecting societal expectations in their work

Krzus (

2011) argued that some business leaders see environmental challenges as risks managed to do-no-harm, whilst others see them as opportunities that support resilience, necessitating an understanding the dependencies between financial and non-financial performance. He cited Siemens AG as demonstrating benefits resulting from an integrated approach to strategic thinking placing sustainable practices at the core.

Othman and Ameer (

2014) studied the interplay between finance and sustainability investment decisions, viewing sustainability as a forward-looking strategic intent. They found that a surplus (deficit) in financial capabilities influenced the financing trajectory.

An earlier review by

Gillan (

2006) considered governance interactions between internal factors (the board, management, capital structures, and rules) and external factors (regulation, capital markets, and external oversight). At the same time,

J. F. Moore (

2006) had suggested that traditional economic organization based on markets and hierarchy was being supplemented or substituted by business ecosystem concepts.

Tsujimoto et al. (

2018) have defined the objective of such ecosystems as: “

to provide a product/service system, an historically self-organized or managerially designed multilayer social network consists of actors that have different attributes, decision principles, and beliefs” (p. 55).

Some researchers studied potential links between corporate governance practice and sustainability disclosure.

Michelon and Parbonetti (

2012) noted that engagement with “community influentials” positively influenced sustainability disclosure. In a study of Pakistani organization practice,

Mahmood et al. (

2018) found that firstly a large board size including a female director and secondly the establishment of a CSR committee helped make better-informed decisions relating sustainability issues and better sustainability disclosure.

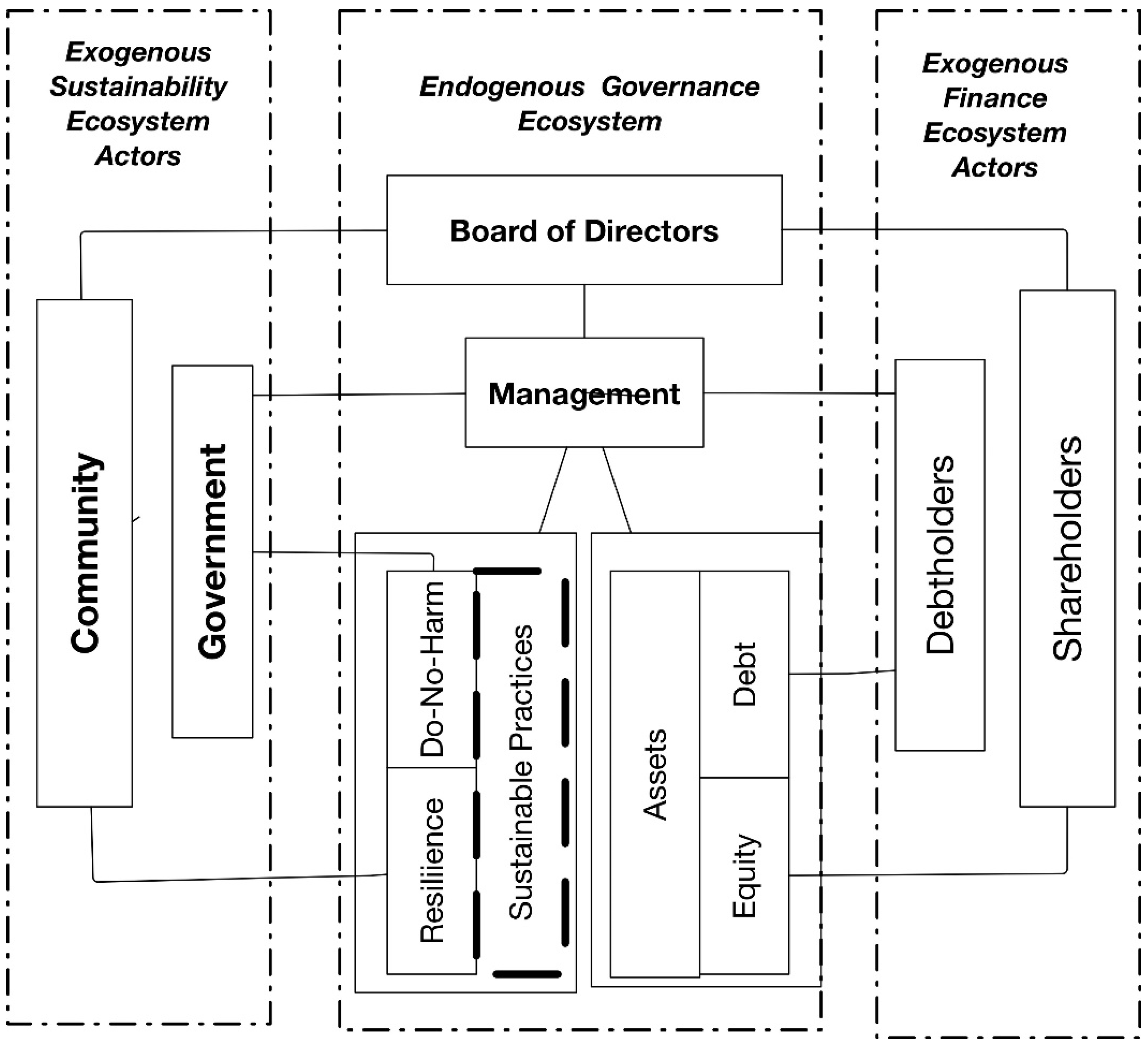

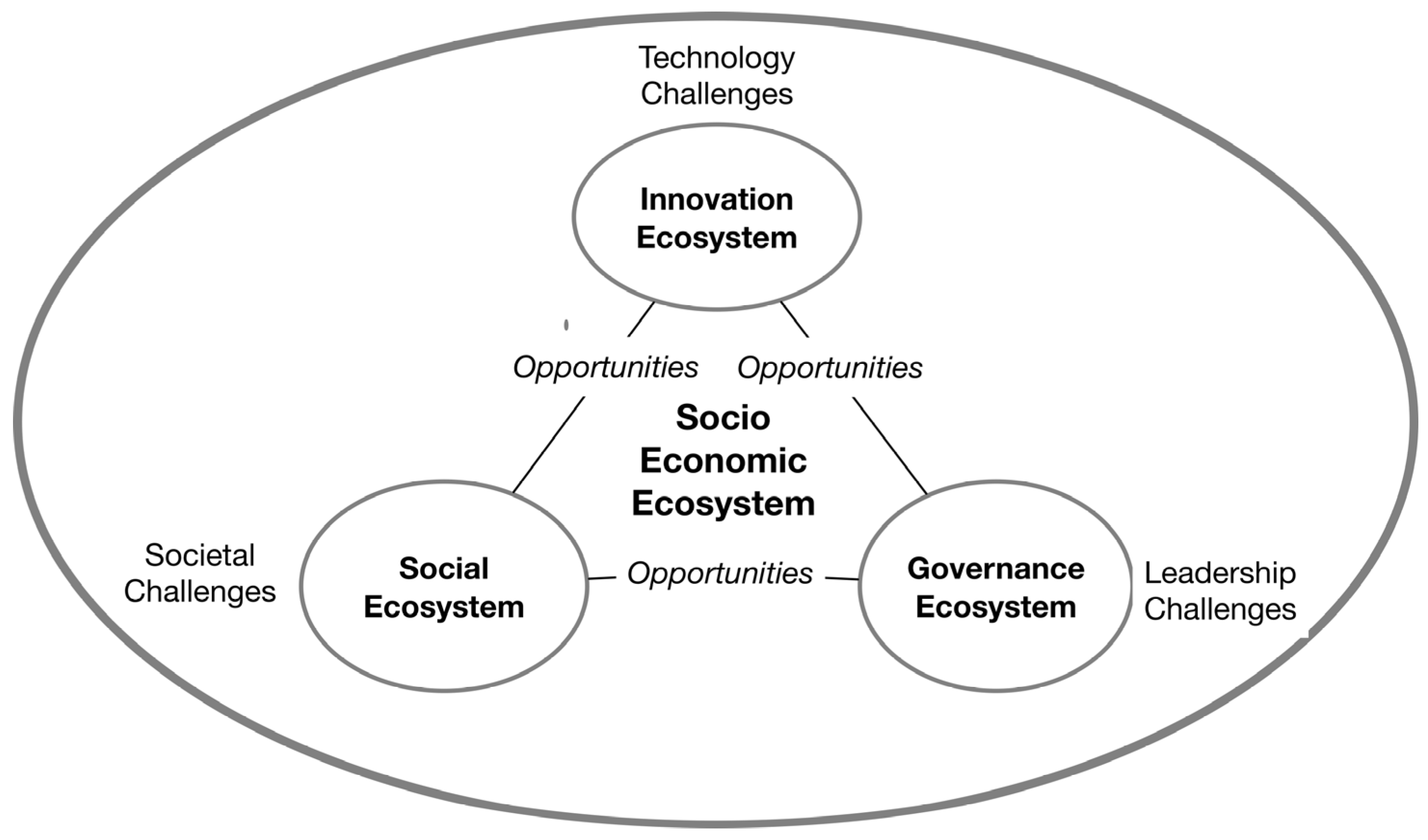

A view of governance ecosystem interactions combining these perspectives is shown in

Figure 1.

In bringing these two exogenous ecosystem actors together, some researchers have suggested that monetizing or placing a long term value on social and environment assets can support better board decision-making (e.g.,

Orlowski & Wicker, 2015;

Schramade et al., 2021;

Roy & Teasdale, 2022), and this may be a topic for further exploration.

2.4. Integrated Reporting Requirements and the Triple Bottom Line

Placing sustainable practices at the core, the idea of “triple bottom line” (people, profit, planet) reporting emerged in the 1990s, with each topic having associated key performance indicators. A review of developments by

Norman and MacDonald (

2004) expressed concerns about the utility and real impact of this approach. In parallel with this, an environmental management systems standard, ISO 14000, was released (

Casto & Ellisen, 1996). Consistent with quality and risk management standards, ISO 14000 incorporated a plan–do–check–act learning cycle to stimulate continuous improvement. It had been observed that auditing against such standards could support new knowledge creation (

Beckett & Murray, 2000). Formal reporting was voluntary and could take different forms. Some concerns were expressed about “greenwashing”—reporting biased or inaccurate representations of actual practice (e.g.,

de Freitas Netto et al., 2020).

A Global Reporting Initiative (GRI—

https://www.globalreporting.org/ accessed on 15 March 2025) sought to institutionalize voluntary sustainability reporting arrangements, but whilst widely adopted, it could have some shortcomings (

Levy et al., 2010). The GRI offers a multi-level, template-oriented structure where an enterprise can configure a set of reports that satisfy their needs for corporate disclosure. A water reporting structure is oriented towards disclosures related to water as a shared resource and to effluent management control.

Siew et al. (

2013) noted that the GRI did not include infrastructure disclosure advice and proposed 21 new indicators related to the environmental, economic, and social dimensions. The point is that multi-dimensional data from many sources have to be assembled in framing a sustainability report. A recent review of GRI practicalities suggested that whilst research on the subject was well established, there were concerns about potential misalignments between the representation of public and private short-term and long-term interests in reporting (

Bais et al., 2024).

Mandatory environmental reporting requirements have been established in some jurisdictions for some time (e.g.,

Holgaard & Jørgensen, 2005). Drawing on 132 observations from German and Italian organizations,

Mion and Loza Adaui (

2019) noted an improvement in the quality of non-financial disclosures after mandatory reporting requirements were introduced. A study of the impact of mandatory sustainability reporting in the UK by

Hummel and Rötzel (

2019) suggested that both standards and reporting incentives shaped a firm’s sustainability disclosure level.

Mazzotta et al. (

2020) examined the impact of making non-financial disclosures on an organization’s credibility, which they viewed as a multi-dimensional construct. They found the 31 Italian companies assessed were regarded as credible in relation to three dimensions: truth, sincerity and appropriateness, and understandability.

Leong and Hazelton (

2019) found that mandatory disclosure could stimulate change if, first, indicators were appropriate for information intermediaries or other intended users; second, information was provided at the appropriate level of aggregation; third, data were comparable to external benchmarks and/or other corporations; fourth, there existed a linkage to networks of other relevant information; and fifth, that sufficient popular and political support existed.

Krzus (

2011) suggested that integrated reporting had implications beyond just combining a financial and sustainability report into one document. He viewed the associated transparency as a critical element of market reform, particularly when social media tools were used in parallel to facilitate engagement. He noted the dominant influence of intangible assets as a component of market value.

A longitudinal study of mandatory reporting practice in Australia by

L. Yang et al. (

2021) identified three emergent themes. The first was an increased level of disclosure in reporting that is associated with environmental regulations. The second was an increasing level of compliance but with some desired outcomes lagging. The third was enhanced identification of emergent issues and follow-up reporting on remedial action, but still with some room for improvement.

Băndoi et al. (

2021) studied the interaction between disclosure, corporate transparency, sustainable development goals, and economic performance, finding that the three context factors had a positive influence on economic performance.

2.5. Research Gaps and Propositions

Our water resilience literature review (

Section 2.1) indicated that the orchestration of timely action, collaborative policy-setting, and resource infrastructure development was needed, but how this orchestration takes place is seen as a research gap. In a similar vein, the circular economy literature (

Section 2.2.1) indicates that learning through experimentation was an essential evolutionary process and that regulations and societal norms may have to adapt to the learning. How this learning takes place is seen as a research gap. It was also noted that circular economy initiatives are embedded in a broader business ecosystem that provides inputs and utilizes output (

Section 2.2.2) and this may also be seen as a potential orchestration issue.

Leong and Hazelton (

2019) suggested that social and environmental accounting research should consider adopting more site-based reporting, ascertain what sustainability information governments already collect, determine what information NGOs need for campaigning purposes, and theorize how to create and link a nexus of accounts. This is seen as a research gap.

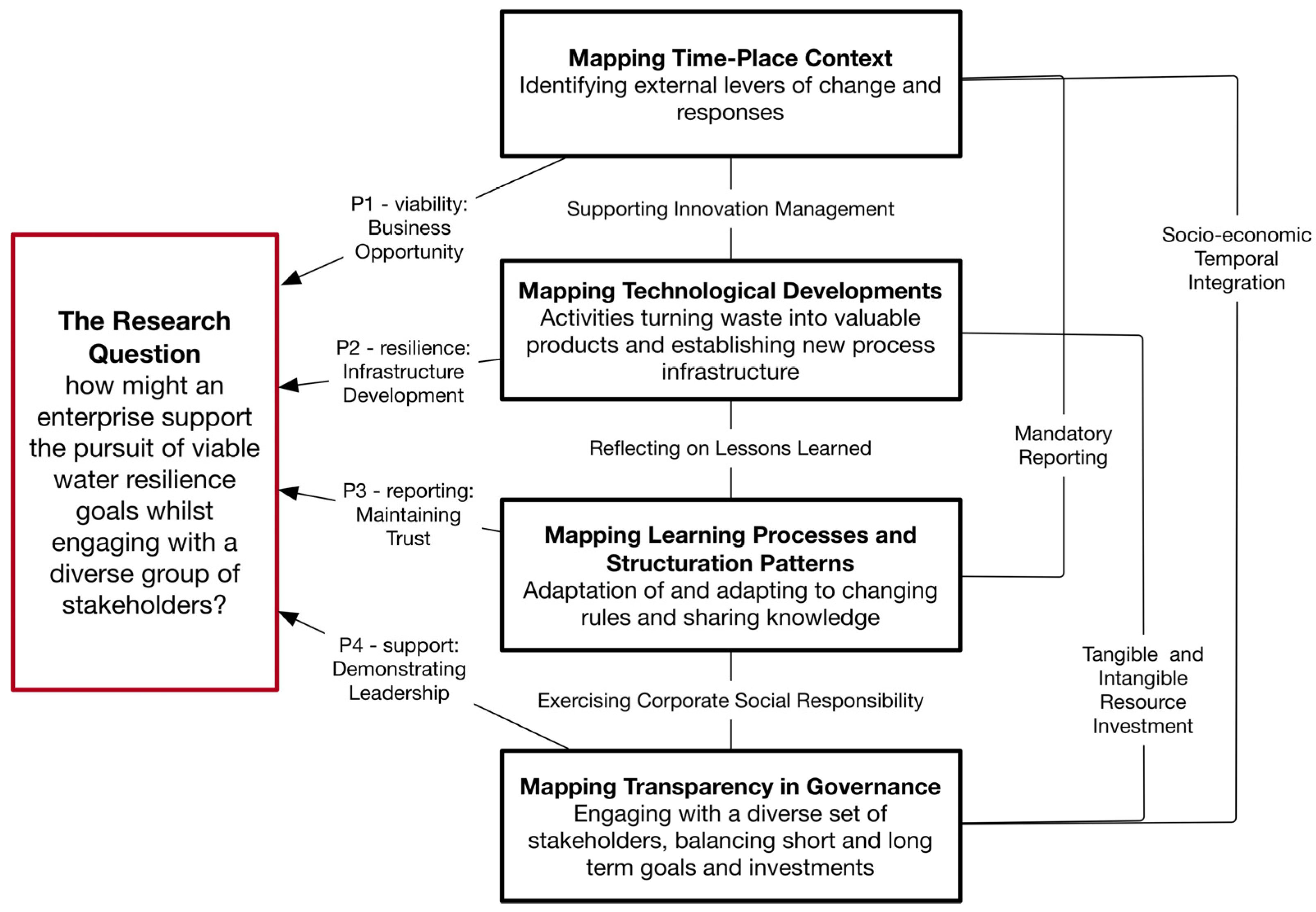

In considering these gaps, we have taken two actions: The first was to identify a model that supports the investigation of multi-factor orchestration dynamics (presented in

Section 2.6). The second was to develop a set of propositions to investigate different aspects of the research question. A structured analysis of thematic narratives was undertaken consistent with the discourse mapping ideas of

Barthes and Duisit (

1975). In this process items of discourse are clustered under segmented units associated with form (the collection of thematic observations), and an integration of these units that conveys meaning (in the context of derived propositions). The outcome was the identification of four propositions:

P1. Time–Place Context: changes in the emerging socio-economic ecosystem an organization is embedded in may be viewed as stimulating new business opportunities and innovation whilst also highlighting the need to balance the pursuit of short- and long-term goals.

P2. Emergent technological developments: these may support the evolution of enhanced operational infrastructure, drawing on investment in both tangible and intangible resources.

P3. Learning and Structuration: reflecting on lessons learned from experimentation may contribute to the satisfaction of mandatory financial and sustainability reporting requirements, demonstrating corporate social responsibility and maintaining organization stakeholder trust.

P4. Establishing transparent leadership in governance through multi-stakeholder sharing of information on investments made and a balanced pursuit of short- and long-term goals to enhance organizational fit with emergent socio-economic ecosystem changes.

We noted there were interconnections between these propositions, and these are illustrated in

Table 2. The null interactions (P1–P1, P2–P2, P3–P3, and P4–P4) are represented as interactions within particular functional ecosystems. The combination of row and column for each proposition identifies associated activities undertaken.

2.6. System Evolution: Working Across Boundaries

Based on the forgoing, we contend that enterprise governance is a continuously evolving activity that informs and is informed by integrated reporting arrangements. In managing sustainable practices enterprises must work across social, professional, and technological boundaries that may vary with time and place (e.g.,

Kakwani & Kalbar, 2020). Rules and resources facilitate (or inhibit) multiple actions and learning that supports adaptation (e.g.,

Voulvoulis, 2018;

Aminoff & Pihlajamaa, 2020).

Beckett and O’Loughlin (

2022) considered interactions within an evolving business ecosystem, drawing on parallels with agile project management practice (e.g.,

Nerur & Balijepally, 2007;

Andriyani et al., 2017a,

2017b) and rules-oriented structuration theory (

Giddens, 1984,

1985;

Edwards, 2000;

den Hond et al., 2012). We test the utility of the

Beckett and O’Loughlin (

2022) model, shown in

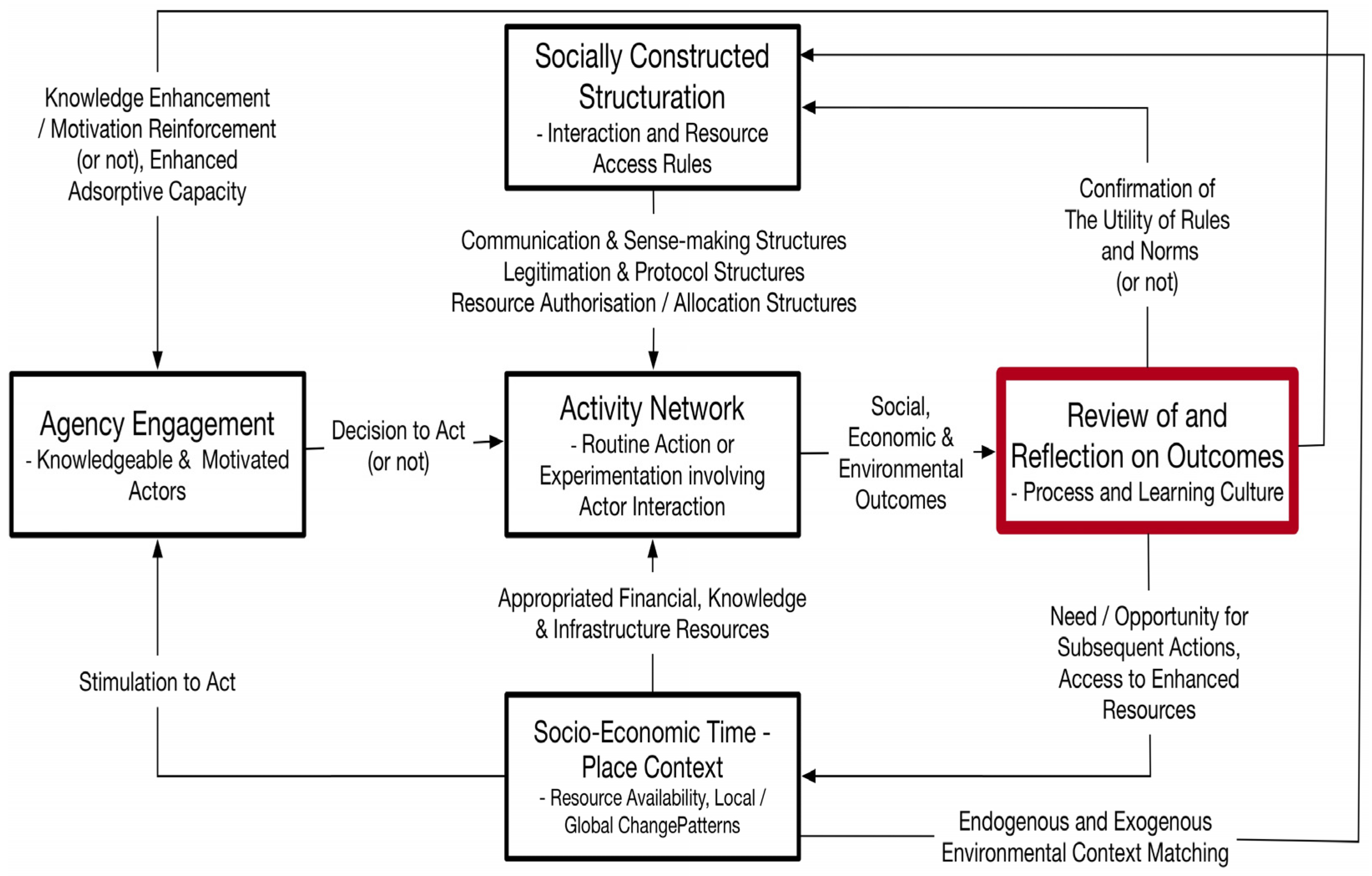

Figure 2 as a case analysis tool in the complex adaptive ecosystem context as suggested by

Phillips and Ritala (

2019). Explanatory comments follow.

Agile Structuration Theory Model (AST)

In the agile structuration theory model, motivated knowledgeable agents act within an institutional (structuration) rules framework to implement a business idea. In the AST, agents also draw on accessible resources within the enterprise and from a broader business ecosystem and then learn from the outcomes. In a particular instance, this learning may lead to enhanced agent absorptive capacity, to an adaptation of an institutional framework associated with governance, and to enhanced ecosystem resources that may be built on in another instance. The review and reflection on outcomes may be organized in different ways in different settings.

In an agile project management setting, this takes place at a micro-level with “retrospectives” being documented at the end of a short-duration task activity. In an annual reporting meso-level context, this involves assessing performance against targets. At a more strategic program macro-level, this involves a focus on the impact of what has been achieved and what has been learned to inform follow-on strategic initiatives.

Formal and informal interaction across boundaries is seen as important in accessing a broader socio-economic ecosystem which may be time–place-sensitive. Consistent with the observations of others (e.g.,

Berends et al., 2016;

Penttilä et al., 2020),

Beckett and O’Loughlin (

2022) suggested there is a need for further research into the review and reflection element of their model, and this is specifically considered in this paper in relation to sustainability governance and reporting implications.

3. Methodology: Longitudinal Case Study

A longitudinal case study was utilized to identify within-case causal relationships in a complex environment, as suggested by

Blatter and Haverland (

2014), and to assess the utility of the agile structuration theory model (AST). This process starts with an observed effect and looks back in time at events that influence that effect. It is consistent with the review of and reflection on activity in the AST. According to

Yin (

2014), case study research is appropriate when investigating “how” questions in a contemporary setting.

We selected a government-owned Australian for-profit water utility, Yarra Valley Water (YVW), as our case study enterprise.

The selection criteria used were as follows:

Established, stable operation and an established pursuit of a water resilience agenda;

Evidence of innovation on multiple fronts and an established market for recovered resources;

Ready access to data related to technical and management aspects of operations from multiple sources such as 120+ company, supplier, and government news releases; 11 years of annual reports; and more than 50 academic engineering and business publications from 2000 to 2023 related to YVW.

The individual documents were assembled in a commercial database system (

https://c-command.com/eaglefiler/ accessed on 15 March 2025) where notes and tags representing particular themes could be associated with particular records. Data were organized into eleven sets of transformational annual events from 2011 plus one pre-2011 set to identify trends and the nature of change taking place. Consistent with the agile structuration theory model developed by

Beckett and O’Loughlin (

2022), shown in

Figure 2, actors, activities, resources, institutional structures, and learning practices associated with each set were identified. A summary-level view of the analysis undertaken exploring four causal relationships reflected in our propositions, time–place context, technological developments, learning processes, and structuration patterns (rules) plus governance transparency, as shown in

Figure 3.

4. Results

The findings are structured following four themes reflected in our propositions P1–P4, namely, enterprise context, collaborative technological developments, learning processes and structuration patterns, and maintaining transparency in enterprise operations.

4.1. Some Matters of Time–Place Context

Yarra Valley Water (YVW) was established under the provisions of the Victorian State Water Industry Act 1994 and began operation on 1 January 1995. From 1 July 2012, it became a corporation subject to regulation by the Essential Services Commission, making payments to the Victorian Government equivalent to the income tax and sales tax that would be payable if it was not a statutory corporation. The corporation is responsible for the control of water supply headworks, major wastewater treatment, and transfer infrastructure and drainage in its region which covers the Yarra River catchment area to the east and north of metropolitan Melbourne, an area covering over 4000 square kilometers. It works with 15 Local Government Authorities.

YVW owns and sustains more than 10,000 km of water mains and approximately 10,000 km of sewer mains. It provides drinking water, sewerage, recycled water and trade waste services to more than 1.9 million residents—almost 30 per cent of Victoria’s population plus over 60,000 businesses across Melbourne’s northern and eastern suburbs. It has a revenue of about AUD 1 billion pa and manages more than AUD 5 billion in assets. YVW directly employs about 600 people. It has won more than fifteen state, national, and international innovation awards for its community, technical, and sustainability initiatives. YVW was the first Australian water corporation to commit to the United Nations Global compact and the pursuit of SDGs.

YVW is pursuing a portfolio of multiple projects that progressively build on prior developments. Multiple actor engagement and strong communication emerged as an important attribute, with active participants being a motivated leadership team, consumers, state government policymakers, specialist suppliers, and industry associations. Innovation activities took place in a succession of overlapping waves or episodes, each one having multiple associated project themes. Individual episodes are outlined in

Table 3.

Ehrenfried et al. (

2022) considered options for YVW’s 2030 circular economy strategy using lifecycle models to map water product flows, nutrient flows, and infrastructure material flows in the pursuit of multiple SDG targets. In 2024, YVW launched a supplementary new map-based tool to show the threat that climate change may have on its infrastructure in the future. The tool uses data from several sources, including the Bureau of Meteorology and Department of Energy, Environment, and Climate Action, and overlayed the data on the YVW service area. It is intended that planning for the worst-case scenario helps YVW assess risks to protect its sites more effectively. This modelling indicated that to manage water supply responsibly, and to keep storages at the levels required to avoid water restrictions, YVW will need new climate-resilient sources of water over the coming decades.

4.2. Collaborative Technological Developments

At the time of writing, YVW was pursuing six innovative project initiatives, including an expanded food waste-to-energy facility, a green hydrogen pilot plant, two expanded sewage collection and treatment facilities, and the establishment of a sustainable water-efficient planned community on irrigation farmland no longer needed by YVW. This has required collaboration with a wider variety of technology partners and research with the Australian Water (industry) Association.

Consistent with the observations of

Sgroi et al. (

2018), technological developments associated with circular economy initiatives took place on several fronts over time, moving beyond water supply and wastewater treatment services to generate valuable products from waste. The YVW common practice was to establish a pilot project, learn from that project, and develop a technology platform that could be replicated in multiple locations.

Table 4 provides an illustration of the capabilities developed or in development.

Over the last decade, YVW has piloted many of these initiatives in one growing peri-urban district providing a greenfield site where wastewater processing, food waste processing, bio-energy production, and hydrogen production can be co-located and parallel drinking water and A-grade processed water distribution arrangements can be put in place. This area is now viewed as an “innovation hub”. A recent initiative to support a community farm by supplying recycled water and allocating some of its buffer zone land won a gold International Water Association innovation award and subsequently attracted national government support. The point here is that establishing a viable baseline activity and business model leads to subsequent scale-up.

YVW undertakes a range of initiatives in parallel. How these relate to circular economy principles is illustrated in

Table 5.

4.3. Learning Processes and Structuration Patterns

The Victorian State Government established a “statement of obligations” following the transition of YVW to for-profit corporation status and has progressively updated it. The obligations relate to pricing, governance, customer and community engagement, risk management, planning, water service delivery, water demand forecasting, contribution to climate and renewable energy goals, and compliance reporting. The early establishment of an innovation culture within YVW provided support to meet these commitments and the impact of external drivers (e.g.,

Crittenden et al., 2011). The innovation cultural norms underpinning both YVW societal and technological engagement has been shared with and adopted by the American Water Institute (

Carter et al., 2017) and has a three-component structure:

Focus on and provide feedback on impact projects;

Maintain evaluation and development capability;

Pursue multi-faceted engagement including consideration of reach.

One example of a social transformation project is called “tap it”—working through schools and sporting clubs to persuade the community to use refillable containers rather than water bottled in disposable plastic containers to reduce plastic waste. YVW has established an independently organized “citizen jury” to help judge what is important in future planning from a community perspective. A form of triple bottom line annual reporting covers both compliance with state government commitments and meeting community expectations. Collaboration continues to evolve in several ways: through project engagement with emerging technologies as indicated in

Table 2, via personnel secondment with other Victorian Government departments, and via mentoring water utilities in developing economies.

Table 6 provides an overview of the YVW innovation process with circular economy project examples.

YVW has embraced agile project management techniques in its digital transformation journey and is more broadly deploying their application. This is built on prior experience in rapidly responding to operational problems and learning through pilot program activities; learning that providing good service can cost less rather than more if handled innovatively (

McCafferty, 2021). Collaborative learning from technology projects and from industry sector initiatives is the norm, e.g., exploring multiple uses for waste biosolids and sharing knowledge in conjunction with industry partners (

AWABS, 2023).

4.4. Maintaining Transparency

YVW uses a variety of social media channels to engage with stakeholders. A Facebook channel provides community subscribers with information about emerging developments and system alerts. A LinkedIn channel is used to share news and engage with partners and current and potential employees. A comprehensive website has primary channels that support client account management, provide help and advice in relation to a number of topics, and share information about faults and works, and an “about us” channel that provides information about YVW functioning.

Specific themes covered in the latter channel are (a) an organization overview, (b) the YVW strategy, (c) how it engages with its communities, (d) information about the YVW community grants program, and (e) a link to a careers page. A ”newsroom” page provides several stories each month relating to a diverse range of YVW initiatives. In a February 2025 article, YVW announced the establishment of an asset services group to lead the implementation of a five-year, AUD 2.6 billion infrastructure enhancement plan.

4.4.1. Governance Arrangements

Effective from 1 July 2012, Yarra Valley Water became a corporation under the Water Act 1989. A study by

Furlong et al. (

2017) provided detailed background to the change in water governance arrangements from a centralized system to a distributed one intended to better meet the needs of a growing metropolitan region. YVW is subject to regulation by the Victorian Government Essential Services Commission and makes payments to the Victorian Government equivalent to the income tax and sales tax that would be payable if the Corporation was not a statutory corporation. The Victorian Government Minister for Water has issued three water corporation statements of obligations to be pursued:

A general statement that includes requirements for price-setting, governance, community engagement, risk management consistent with ISO 31000 (

International Standards Organisation, 2018a), supply planning including modelling for climate change and a drought response plan, water service provision that includes managing assets, and compliance auditing.

A statement of water system management requirements to support equitable engagement with the broader state water storage and distribution network.

A statement of requirements to support greenhouse gas emission reductions and renewable energy use.

The YVW board has six female and four male members, including the chair and the operational managing director. Some members have prior water industry executive management and board experience, some are experienced in community engagement (including engagement with indigenous communities), and some have a technology background. The board is responsible for setting strategic direction, establishing goals for management and monitoring their achievement, and for monitoring the performance of the business. Day-to-day responsibility for operations and administration is delegated by the board to the managing director and the executive team. Members of the executive team are invited to board meetings when their areas of operational responsibility are being considered.

The non-executive chair and non-executive directors are appointed by the minister for water. The managing director is appointed by the board. A board charter clearly sets out clearly the role, responsibilities, and powers of the board and incorporates all aspects of board governance, along with referencing the source of the items included in the charter. Consistent with the charter, the board undertakes a review of the charter at least every three years and may amend the charter if required at any time. Sub-tier charter commitment statements have been customized to reflect the needs of residential, business, trade waste, and recycled water customers.

The board has established three committees covering the following:

Finance, audit, and risk management;

Customer, asset, and sustainability;

Leadership, culture, and wellbeing.

As noted earlier, in 2017, the YVW board established a “citizens jury” that every few years considers information on pricing, service provision, and other expectations to support planning over the next five years. The aim is to consider realistic water pricing given stakeholder priorities. The “jury” has some 50 members representing a cross-section of stakeholders and its operation is facilitated independently. The first “citizens jury” identified seven focus areas with associated target measures which YVW reported against annually. The second “citizens jury” was given the specific remit—“With the challenges of climate change and population growth in mind, the quality and reliability of water supply and sewerage services are critical needs. Clear communication and transparency are essential to empower and inform users to access resources in a respectful, equitable and sustainable way”. A specific question was: How can water and the environment be protected and respected, for and by present and future generations? Indigenous community elders were included in the jury for the first time and their presentations on caring for the land based on centuries of experience influenced subsequent recommendations. Twelve recommendations for 2023–2028 focus areas were provided, and these were consolidated into six generic outcomes with year-by-year targets.

4.4.2. Integrated Reporting

The YVW board has approved the adoption of an integrated management system policy that brings together compliance with ISO 9001 quality management standard, (

International Standards Organisation, 2015), ISO 14001 environmental management standard, (

International Standards Organisation, 2017), and ISO 45001 occupational health and safety management standard, (

International Standards Organisation, 2018b). Maintaining accreditation with these standards requires regular auditing of YVW operations. A ten-year strategic plan was released in 2020, and annual reports provide updates on its realization. Three strategic plan themes are identified: (a) helping communities thrive, (b) transforming around the customer, and (c) leading for our environmental future. The

YVW (

2022) climate resilience plan also reflects these values. By way of example, the 184-page 2023–2024 annual report contains the following:

A section introducing YVW and its operational context with messages from the chair and the managing director.

Twenty pages of 2023–2024 highlights structured around elements of the strategic plan.

Seventy-two pages framed as “delivering value”. This includes outlines of multiple livability outcomes (including resilience considerations showing where the input water supplies come from), environmental outcomes, compliance with regulatory requirements, and a summary of financial indicator outcomes. Both information and associate measures are reported.

Sixty-six pages of detailed operational and financial reporting

The 2023–2024 operational performance in relation to citizen jury expectations was detailed in a separate report on the six outcomes identified via the “citizen jury” process. Whilst performance targets were met in most areas, where there was a need for corrective action (3 of 17 measures), an action plan was proposed.

By comparison, the 70 page 2011–2012 annual report contained the following:

A section introducing YVW and its operational context with messages from the chair and the managing director.

One page giving an operational overview under the headings of customer, culture, environment, and efficiency.

Five pages providing a corporate governance statement.

A statement that risk management practices are in line with anational standard (AS/NZS ISO 31000:2009).

Five pages presenting a financial summary.

Forty-five pages presenting the financial report.

Seven pages relating to water resilience matters. This showed that water usage measured in terms of liters per capita per day had reduced to about 60% of prior norms, and sustaining this level has been an ongoing target.

Differences between the 2011–2012 and the 2023–2024 annual reports shows an increase in the attention to sustainability and the extent of reporting supplemented by broader use of social media supporting the maintenance of transparency.

5. Discussion

In the following, we consider the alignment between case enterprise actions and theoretical perspectives. We start by comparing observations from the case with those from the water resilience literature, illustrated in

Table 1, followed by implications for governance and reporting in illustrated in

Figure 1. We then consider the case observations in the context of the agile structuration model (ASM) dynamics illustrated in

Figure 2.

5.1. Contribution to Practice: Water Resilience Actions

Table 7 shows a strong alignment between the themes emerging from our water resilience literature survey and the practical actions taken by the YVW case enterprise.

It may be noted that the case study 2023–2028 plan is called the “climate resilience” strategic plan in recognition of the water–energy nexus. This plan may be viewed as an enactment of the themes identified in the literature and has three pillars:

A focus on core activities represented as ensuring water security, managing climate-resilient assets, and greenhouse emissions reduction.

Providing strong foundations represented as embedding climate resilience, understanding climate risks, and strengthening partnerships for climate resilience (e.g., YVW has established water efficiency programs with 21 major customers).

An increasing focus on emergency management, preparation, and recovery; on building financial resilience; and on supporting community and environment resilience.

5.2. Contribution to Practice: Implications for Governance and Reporting

The YVW Board has two kinds of governance responsibilities. The first is the responsibility for enterprise operations that are influenced by both sustainability and economic considerations, as represented in

Figure 1. The second is a shared responsibility for water governance beyond its designated service area. We discuss each in turn. The Global Reporting Initiative has an orientation towards disclosure, and whilst the YVW annual reports supply information about compliance with external requirements, the focus is on transparency supporting ongoing stakeholder engagement.

5.2.1. Enterprise Governance and Reporting Scope

The literature (

Section 2.3) indicates that some particular board attributes (diversity, independence, and size) and practices (use of a sustainability committee, CEO role, disclosure, and transparency) supported a sustainability agenda. The YVW annual report has a section providing information on the background of each board member and which board committees they are engaged with. The annual report also identifies ten senior management staff members with brief descriptions of the roles and responsibilities of each one.

The YVW board is expected to utilize assets provided by its shareholders and other stakeholders to deliver value-in-use and to appropriate benefits to those actors. This is reflected in the maintenance of profitable operations and, for instance, in making community grants available.

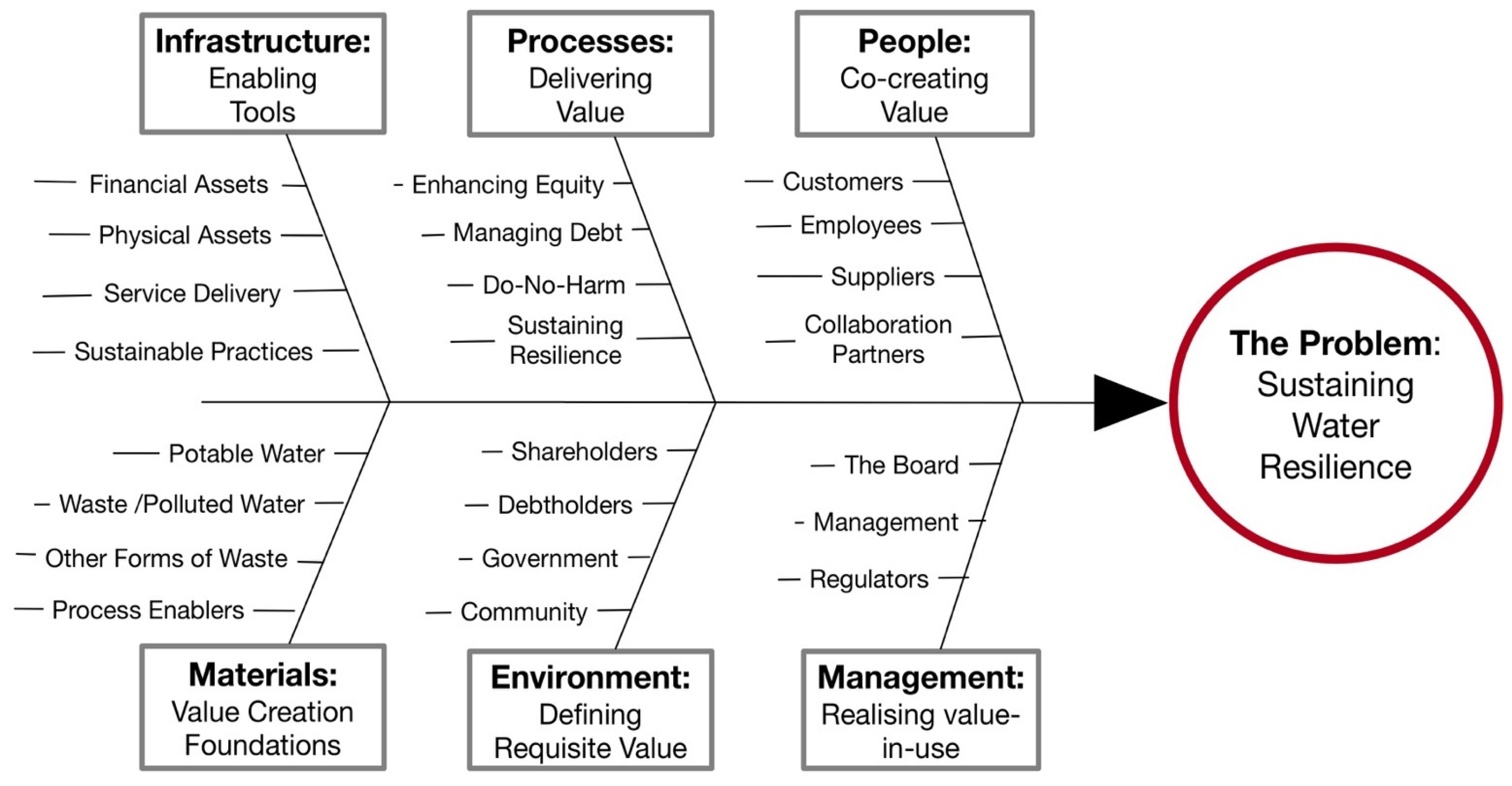

Multiple factors influence the realization of water resilience, but the adoption of circular economy principles is at the core. The case study business ecosystem actors, activities, and resources supporting problem resolution matters that need to be governed and reported on are outlined from a value perspective in the Ishikawa diagram shown as

Figure 4, drawing on our causal process tracing analysis.

5.2.2. Water Governance and Reporting Scope

As noted in the literature review (

Section 2.3), there is need for multiple disciplines to be involved in Integrated Water Resource Management that reflects water governance requirements. Matters of equitable water allocations across a diverse range of users were raised in the context of finding a balance between the public nature of the resource and private rights to it. In 2017, the Victorian State Government released an Integrated Water Management (IWM) framework to support water resilience planning with shared decision-making. This followed a period of research and consultation; the government specified who should be involved in a formally established IWM forum that was expected to meet three to four times each year to establish and monitor development plans. Sixteen IWM forum areas across the state were identified, each having particular kinds of water resilience imperatives. Multidisciplinary working groups were established to progress particular actions. Forum partners “are encouraged to put in place self-assessment measures at defined intervals during the progression of collaborative planning”. Individual organizations should also consider adding IWM key performance indicators (KPIs) to their own reporting mechanisms. This could include the outcomes to be achieved in the IWM plans. The Global Reporting Initiative standard relating to water suggests “a need for a description of how water-related impacts are addressed, including how the organization works with stakeholders to steward water as a shared resource, and how it engages with suppliers or customers with significant water-related impacts”. In the YVW case, its annual report documents where its water supply comes from (three large river/catchment systems and a desalination plant) and how much is supplied from each source, and summarizes progress on regional IWM activities it is responsible for.

5.3. Contribution to Practice: Balancing Efficiency and Effectiveness

The YVW 2023 “climate resilience” strategic plan calls for the maintenance of supportive financial resilience. Investment in financial and physical infrastructure redundancy is needed to establish and maintain service and organization resilience, but this may be seen as inefficient. In the YVW case, the state government had invested in a seawater desalination facility, stimulated by a long period of drought. When more normal conditions subsequently retuned, some viewed this as a waste of public money, but as the population has increased, it is now used more frequently. This provides an example of balancing long- and short-term views.

Herrmann et al. (

2008) studied the management of the efficiency and effectiveness dialectic in social spending, observing a need for a broader focus on the quality of outcomes. For instance, YVW has invested in renewable energy, which both reduces its input costs and supports a broader sustainability agenda. A board review of outcomes reflected in customer pricing trends over a decade indicated that whilst prices had increased, there was a significant relative reduction shown after adjustment for inflation. The inference we draw is that balancing short and long term investments to support organizational effectiveness can still support long term efficiency.

Another dialectic to be confronted (referred by some authors and balancing yin and yang philosophies, e.g.,

Nguyen et al. (

2008)) is how financial viability is maintained whilst encouraging clients to buy less of the primary product (potable water). The YVW responses have been to (a) offer an alternative to service some customer needs (recycled water) and (b) supplement income via associated lines of business (processing food waste). The point here is that balance can be achieved, but this requires multi-dimensional action.

5.4. Contribution to Theory: Agile Structuration Theory (AST)—Incorporating Rules for the Game

AST brings together three theoretical perspectives that characterize the dynamics of enterprise operations within a broader business ecosystem:

Structuration Theory—The evolution of overarching rules and norms that support coherent operations, e.g., analogous to the data exchange protocols that support the internet. Drawing on the three elements of structure—signification/communication, legitimation/cultural norms, and domination/resource access and allocation—this theory has been used in accounting system research (

Macintosh & Scapens, 1990;

Busco, 2009), in helping to understand aspects of e-government systems assimilation (

Hossain et al., 2011), and in studying the organizational dynamics associated with environmental reporting (

Correa-Ruiz, 2019). In the YVW case, rules and norms have been enunciated through the establishment and tracking of strategic plans and through the maintenance of an innovation culture.

Agile Project Management Theory—Practices that support adaptation to changing circumstances by addressing and learning about complex problems via a succession of pilot program activities. In the YVW case, the actual dynamics were consistent with the observations of

Kavin and Narasimhan (

2017), who considered the influence of industry clock speed on innovation practice. They noted that whilst low-speed (e.g., the water industry in our case) and high-speed (e.g., the IT industry) sectors may follow similar innovation practices, how these practices were used differed. In the YVW case, the digital technology initiatives are developed faster than major process initiatives.

Business Ecosystems Theory—Recognizing that a particular enterprise draws on and contributes to an external socio-economic ecosystem. The AST contains several feedback/feedforward linkages between its components, and these linkages frame the following discussion. The socially constructed structuration components are shaped via context matching with the socio-economic time–place context and via feedback from experience utilizing previously established structures (structuration theory “duality of structure”).

D. R. Moore (

2013) utilized an adaptation of structuration theory to study the evolution of sustainability accounting practice in a regional Australian Water Board through the 2000s as regulatory requirements issued by different government bodies emerged. This helped identify potential conflict between political/economic and environmental requirements. Initially, YVW compliance with environmental management system requirements was a primary industry focus (e.g.,

Schaefer, 2007). The subsequent adoption of integrated water management practices to support resilience involved engagement with a broader range of business ecosystem actors.

Institutionalization actions framing rules for the game were considered at three levels: political/regulatory, industry sector norms, and individual enterprise-level responses. YVW adopted a relatively aggressive approach towards environmental sustainability in the mid 2000s, recognizing that (consistent with agile thinking) “every journey starts with a single step” (

Pamminger & Crawford, 2006). They started with a focus on mindset issues, and these philosophies (mindset and small steps) have continued to evolve ever since. At the individual enterprise level, YVW believes it has harmonized multi-faceted issues by firstly associating monetary value with efficiency, environmental, social (customer), and internal cultural action responses, and secondly including measures of performance in these four dimensions in its annual reporting (review and reflection in the AST model).

The establishment of a “community jury” provides another independent review process that influences legitimation structures. The YVW innovation process (

Table 6) includes community and partner engagement, which may be viewed as adopting structures of signification; a focus on impact, which may be associated with structures of legitimation; and capabilities, which may be associated with structures of domination. From structuration perspective, we would suggest YVW has overlaid government and community expectations with an entrepreneurial mindset.

A review and reflection process drawing on experience from routine and project activities undertaken may also enhance agent absorptive capacity supporting effective innovation (e.g.,

Kostopoulos et al., 2011). YVW specifically invests in this capacity via projects involving secondment to international collaborator organizations and mentoring water utilities in developing economies but also learns from interaction with technology providers as expanded process capabilities are developed (e.g., as indicated in

Table 3). At both an enterprise and industry level, the review and reflection process presents needs/opportunities for subsequent action, contributing knowledge and infrastructure resources to the broader socio-economic ecosystem YVW is embedded in.

The point to be made here is that review and reflection processes covering multiple stakeholder perspectives are an important part of YVW’s innovation management practice that either endorses or adapts that practice over time. This resonates with the ideas of

Barnabè and Nazir (

2021), who suggest that integrated reporting practices and systems thinking can support the conceptualization and deployment of circular economy principles. If there is an emergent operational issue, a problem-solving team assembles observations from all associated stakeholders in pursuing a resolution, a process analogous to user story collection in agile IT systems methodologies.

Through its industry association connections, YVW also shares and captures knowledge in targeted collaborative projects (e.g.,

AWABS, 2023). As implied in

Figure 1, these contributions and/or external drivers (e.g.,

Table 2) provide a stimulation for people to act.

5.5. Contribution to Theory: Orchestrating Governance and Reporting

The literature suggested a research gap in the relationship between governance and reporting that supported a sustainability agenda, with a need to orchestrate a multiplicity of activities. In this discussion, we consider the orchestration of board and of reporting activities drawing on the theoretical models (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) introduced in this paper. This theoretical contribution illustrates how these models work together.

We start with a discussion of governance orchestration. In the AST model, motivated and knowledgeable actors, including boards, draw on established absorptive capacity (e.g.,

Zahra et al., 2009;

Lu et al., 2021) to interpret a stimulation to act and decide on activities to progress. Viewing the board as one such actor, our literature review (

Section 2.3) identified expanded board attributes that would support both financial and sustainability considerations. Examples of activities progressed are shown in row D and column 4 in

Table 2. The absorptive capacity aspect may be a topic for future research.

The notion of engagement with various kinds of functional ecosystems (e.g., the shaded diagonal cells in

Table 2) is a recurring theme in this paper, with the board and management being responsible for making/maintaining connections with other semi-autonomous actors.

Figure 1 presents a governance activity ecosystem view where the board has three primary connections: an internal connection with management, and external connections to shareholders, and the community served. The management connections establish sustainable practice and asset management action characterized as resilience, providing reliable service in demanding conditions, and as equity maintenance/growth. In the YVW case, asset management involves both intangible agency assets (knowledge and culture) and physical resource assets (YVW has a turnover of about AUD 1 billion and manages physical assets valued at about AUD 6 billion). Management also has responsibility for orchestrating debtholder (financial) and government connections (represented as compliance with do-no-harm regulatory requirements, e.g., environmental and health/safety standards). The board has a responsibility to see that these activities are managed appropriately, relying on both internal reporting and external auditing associated with mandatory reporting for this purpose. In the YVW case, reporting on the measures of performance established in conjunction with the “citizen jury” may be viewed as reporting to the community on resilience. Mandatory annual reporting, as illustrated in the YVW case, provides feedback to both shareholders and the community.

Leong and Hazelton (

2019) reported that mandatory disclosure could stimulate change. The AST model indicates the process of review and reflection on outcomes of operational action identifies three kinds of change:

- -

A potential need to modify governing structuration rules or cultural norms related to communication/communication sensemaking (e.g., adapting the annual report content and style in the YVW case), legitimation (e.g., contributing to broader community-integrated water management requirements in the YVW case) and resource use authorization/allocation (e.g., the ability to administer water use restrictions in the YVW case).

- -

Potential knowledge enhancement/motivation reinforcement and absorptive capacity (e.g., the expansion of transdisciplinary activities in the YVW case).

- -

A need/opportunity for subsequent action (e.g., “taking action on unsatisfactory citizen jury KPIs” in the YVW case) and providing access to enhanced resources that may support future actions (e.g., extending the use of sewage biodigester technology to process food waste in the YVW case).

These outcomes emerge from a review and reflection process, which Beckett and O’Loughlin indicated was under-researched in the AST model context. We view mandatory reporting and auditing as part of that process, both supported by and facilitating the reinforcement of a learning culture. We had noted earlier that some standards (e.g., relating to environment management systems—ISO 14000) were organized around a plan–do–check–act learning cycle.

Beckett and Murray (

2000) found that a combination of a learning culture and framing auditing as a normal business activity could enhance the knowledge base and absorptive capacity of manufacturing organizations. They identified three audit learning opportunities: firstly, in preparing for an audit, collecting requisite data, and reflecting on them; secondly, learning from the experience of the auditor during the process; and thirdly, in following up corrective actions.

Hoole and Patterson (

2008) found that in the social organization sector, evaluation processes stimulated the development of a learning culture given management support and facilitative infrastructure.

Alberti et al. (

2022) studied audit firm culture, noting that better-quality outcomes emerged when the leadership emphasized professionalism over commercialism and learning was facilitated through systems, the integration of specialists, and interpersonal interactions amongst auditors. The message here is that there is learning

for auditing and learning

from auditing, but this requires governance supporting a learning culture.

In the YVW case review and reflection activities were also part of the responsibilities of Board committees. One committee specifically focused on leadership, culture, and wellbeing, promoting an innovation culture in particular.

5.6. Contribution to Theory: The Integration of Multiple Perspectives

The ecosystem analogy is mentioned in a variety of literature stream contexts. We presented propositions based on our literature survey and classified interactions between them in

Table 2, representing integrating mechanisms as socio-economic, innovation, societal, and governance ecosystems. Another recurring theme in the literature was the need to transform challenges into opportunities, as exemplified in the YVW case. These are combined in the model shown as

Figure 5, which identifies three classes of emergent opportunity as briefly elaborated in the following:

Socio-technical system opportunities. Emergent technology may be viewed as providing an opportunity to pursue social goals as illustrated the YVW recycling case (

Table 5). This may be seen as consistent with the views of

Laszlo (

2018) regarding the need for leadership in the evolutionary design of combined socio-technical and ecological system solutions.

Giudici et al. (

2024) studied EU investment practices supporting sustainability goals and emphasized need for trans-disciplinary solutions combined with agile and adaptive approaches to organizational learning.

Governance technology systems opportunities. YVW utilizes a variety of IT tools to support community and professional stakeholder engagement and is using digital modelling tools to support management decision-making. There has been recent interest in how artificial intelligence tools may support governance, e.g.,

Hilb (

2020) and

Zuiderwijk et al. (

2021), and in the need for governance of artificial intelligence systems, e.g.,

Taeihagh (

2021).

Governance social opportunities. These may be considered from a corporate social responsibility (CSR) perspective. In the YVW case, both transparent reporting and investment in community projects reflect this kind of interaction.

T. K. Yang and Yan (

2020) used the ecosystem concept as a lens to investigate how creating shared values as an aspect of CSR programs could lead to a variety of enterprise operational and business initiatives.

Joo et al. (

2017) viewed CSR as an investment in building a sustainable business ecosystem and investigated opportunities to integrate social and economic values to enhance firm competitiveness, noting that established social capital could increase the survival rate of ecosystem members after an external shock.

The point to be made here is that the multitude of activities to be addressed in the pursuit of sustainability goals draw on and contribute to the continuing evolution of networks of independent but interdependent networks of actors, activities, and resources.

6. Conclusions

With respect to the research question “How might an enterprise support the pursuit of viable water resilience goals whilst engaging with a diverse group of stakeholders?”, we conclude that integrating circular economy principles in water resilience whilst maintaining traditional services, and implementing change, is critical for a successful transition. This integrated approach has positive implications for corporate governance and sustainability reporting. The longitudinal case study, based on an interconnected ecosystem perspective, provides a “best practice” example of learning through experimentation, interactions with evolving social norms and regulations, and the conversion of waste into valuable product within a broader regional socio-economic context, as noted in separate studies in the literature. The case was interpreted in terms of four propositions developed from the literature and we add to this compilation by identifying interactions between the proposition (

Table 2). This indicates such interactions are moderated by engagement with associated socio-economic, innovation, social, and governance ecosystems. We make a further contribution to the literature by illustrating how these interactions may be interpreted as opportunities in response to challenges (

Figure 5).

The associated ecosystem activity mechanism has been explored using an agile structuration theoretical model (

Figure 2) to help understand how a succession of projects within longer-term waves/episodes of innovation support circular economy outcomes. One aspect of this model is a review and reflection process associated with each activity and an individual project episode (related set of activities).

We make a theoretical contribution by illustrating how corporate governance and mandatory reporting may be viewed from this perspective. This reflection process provides feedback to engaged actors to enhance their absorptive capacity, indicates where norms/rules may be beneficially adapted (

Giddens, 1984, duality of structure concept), and identifies enhanced resources that may help form a platform supporting the next project or episode. This holistic view of the dynamics at play complements specific enabling innovation and circular economy factor condition studies identified in the literature.

Components of a water utility innovation management framework that has evolved over time via global collaboration are outlined (

Table 6). Our research also adapted a recent circular water economy model emerging from a joint academia/industry study that showed interactions between the management of rain and stormwater assets, water and wastewater treatment and distribution, associated energy generation and consumption, food waste management, and inputs to agriculture (

Table 4).

The current practitioner focus is on outcomes to achieve the UN Sustainable Development Goals, and the case shows how this may be progressively achieved through a succession of modest pilot projects where the successful outcomes help build a platform for further innovation. Consistent with the innovative company observations of

Keeley et al. (

2013), YVW mixes and matches multiple innovations that demonstrate how circular economy principles in water resilience are integrated for corporate governance and sustainability reporting.

YVW governance shows good alignment with a model derived from the literature (

Figure 1) that combines the perspectives of financial and sustainability ecosystem actors with internal ecosystem actors. Comprehensive sustainability reporting is founded on the intentions of enterprise strategic plans that bring together operational and sustainability short-and long-term requirements. As a result, in the interests of transparency, the size and scope of the case annual report has more than doubled over the last decade, but the results captured come seamlessly from the integrated management approach adopted.

Limitations and Future Research

Whilst drawing on one case may be seen as a limitation, reference to “the identified causal configurations and mechanisms” (

Blatter & Haverland, 2014) may be explored in other water circular economy cases in different settings (e.g.,

Rickfält, 2019) to examine the four propositions enunciated in this paper. Several case studies could be a topic for future research drawing on the agile structuration model presented in this paper. The monetization of assets such as waste and social capital was noted in the case presented and in the literature, and how this is used in decision-making could be a topic for further research. Finally, how the absorptive capacity of the board and the organization is enhanced by engagement with mandatory reporting may be another topic for further research.