How Do Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital Impact the Investment Efficiency of Listed Firms in Nigeria?

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Conceptual Review

2.1. Segment Disclosure

2.2. Investment Efficiency

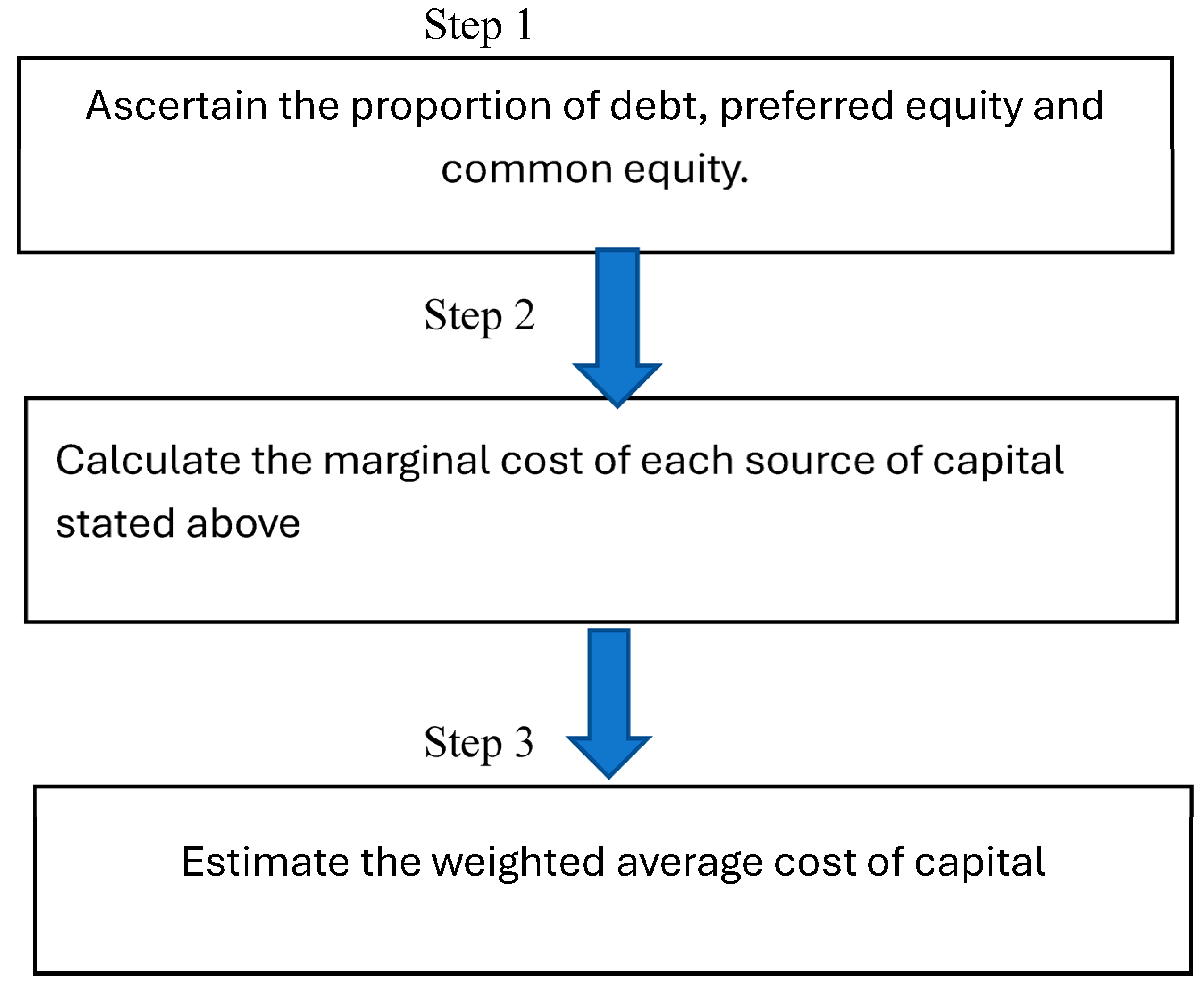

2.3. Cost of Capital

3. Empirical Review

3.1. Extent of Segment Disclosure

3.2. Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital

3.3. Segment Disclosure, Cost of Capital, and Investment Efficiency

4. Theoretical Underpinning and Hypothesis Development

4.1. Signalling Theory

4.2. Agency Theory

5. Methodology

Model Specification

6. Findings and Discussions

6.1. Descriptive Statistics

6.2. Correlation Matrix Analysis

6.3. Effect of Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital on Investment Efficiency

7. Conclusions

7.1. Policy Implications

7.2. Limitations of Study and Future Research Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Abbas, N., Ahmed, H., Malik, Q. A., & Waheed, A. (2018). Impact of investment efficiency on cost of equity: An empirical study on Shariah and non-Shariah compliance firms listed on Pakistan Stock Exchange. Administrative Review, 2(3), 307–322. Available online: https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-60206-5 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Aboud, A., & Diab, A. A. (2018). The impact of social, environmental and corporate governance disclosure on firm value evidence from Egypt. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 8(4), 442–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboud, A., & Roberts, C. (2018). Managers’ segment disclosure choices under IFRS 8: EU evidence. Accounting Forum, 42(4), 293–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelegan, O. J. (2009). Capital market development and investment efficiency in Nigeria. Savings and Development, 33, 113–132. Available online: https://aisberg.unibg.it/retrieve/handle/10446/27432/9075/ADELEGAN%202-2009.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Adeyemi, S. B., & Fagbemi, T. O. (2010). Audit quality, corporate governance and firm characteristics in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Management, 5(5), 169–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeyemi, S. B., & Oboh, C. S. (2011). Perceived relationship between corporate capital structure and firm value in Nigeria. International Journal of Business and Social Science, 2(19), 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Agoraki, K. K., Giaka, M., Konstantios, D., & Negkakis, I. (2024). The relationship between firm-level climate change exposure, financial integration, cost of capital and investment efficiency. Journal of International Money and Finance, 141, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajide, M. F. (2017). Firm specific and institutional determinants of corporate investments in Nigeria. Future Business Journal, 3(2), 107–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinlo, O. O., & Sule, D. F. (2019). Voluntary disclosure and cost of equity capital in Nigerian banks: An empirical study. Ife Journal of Economics and Finance, 8(12), 61–72. [Google Scholar]

- Akinsulire, O. (2006). Financial management and evaluation of cost effectiveness (4th ed., Vol. 73, pp. 543–551). El-toda Ventures, Ceemol Nigeria Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Hadi, A., Hasan, M. M., Taylor, G., Hossain, M., & Richardson, G. (2017). Market risk disclosures and investment efficiency: International evidence from the Gulf Cooperation Council financial firms. Journal of International Financial Management & Accounting, 28(3), 349–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsayegh, M., Rahman, R. A., & Homayoun, S. (2022). Corporate sustainability performance and firm value through investment efficiency. Sustainability, 15(1), 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, P., Filip, A., & Moldovan, R. (2016). Segment disclosure, quality and quantity under IFRS 8: Determinant and the effects on financial analysts’ earnings forecast errors. International Journal of Accounting, 51(4), 443–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anwar, R., & Malik, J. A. (2020). When does corporate social responsibility disclosure affect investment efficiency? A new answer to an old question. SAGE Open, 10(2). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ardianto, A., Anridho, N., Ngelo, A. A., Ekasari, W. F., & Haider, I. (2023). Internal audit function and investment efficiency: Evidence from public companies in Indonesia. Cogent Business &Management, 10(2), 2242174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assad, N., Jaafar, A., & Zervopoulos, P. D. (2023). The interplay of real earnings management and investment efficiency: Evidence from the U.S. Cogent Business & Management, 10(2), 2237174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakrishnan, K., Core, J. E., & Verdi, R. S. (2014). The relation between reporting quality and financing and investment: Evidence from changes in financing capacity. Journal of Accounting Research, 52(1), 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, S., Kim, O., & Lim, L. (1999). The usefulness of industry segment information (Working paper). Baruch College-City University of New York. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228306664_The_Usefulness_of_Industry_Segment_Information (accessed on 22 September 2024).

- Bens, D. A., Berger, P. G., & Monahan, S. J. (2011). Discretionary disclosure in financial reporting: An examination comparing internal firm data to externally reported segment data. Journal of Accounting Review, 86(2), 417–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P., & Hann, R. (2003). The impact of SFAS No. 131 on information and monitoring. Journal of Accounting Research, 41, 163–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P., & Hann, R. (2007). Segment profitability and the proprietary and agency costs of disclosure. The Accounting Review, 82, 869–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, N., Chang, H. S., & Chiorean, R. (2022). Regulatory interventions in response to non-compliance with mandatory derivatives disclosure rules. Review of Accounting Studies, forthcoming, SMU Cox School of Business research paper No. 21-21, Singapore Management University School of Accountancy research paper No. 2022-145. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3979231 (accessed on 10 July 2024). [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G. C., & Hilary, G. (2006). Accounting quality and firm-level capital investment. The Accounting Review, 81(5), 963–982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, G. C., Hilary, G., & Verdi, R. S. (2009). How does financial reporting quality improve investment efficiency? Journal of Financial Economics, 48, 112–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, B., García, L., Juan, M., Tribo, G., & Joseph, A. (2015). Segment disclosure and cost of capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 42(3–4), 367–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. A. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. The Accounting Review, 72(3), 323. [Google Scholar]

- Botosan, C. A., Huffman, A., & Stanford, M. H. (2021). The state of segment reporting by U.S. Public Entities: 1976–2017. Accounting Horizons, 35(1), 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. A., & Plumlee, M. A. (2002). A re-examination of disclosure level and expected cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 40, 21–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botosan, C. A., & Stanford, M. (2005). Managers motives to withhold segment disclosures and the effect of SFAS No. 131 on analysts’ information environment. The Accounting Review, 80, 751–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bova, F., Luo, Z., & Yang, L. (2024). Geographic segment disclosures and proprietary costs. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5022683 (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Bushman, R. M., & Smith, A. J. (2001). Financial accounting information and corporate governance. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 32(1–3), 237–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, C., Cao, V. N., Clinch, G., & Sek, M. (2024). Real effect and segment disclosure policy: Implications for investment decision, cost of capital and firm value. AASB Research Centre Working Paper No. 24-05. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4957270 (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Hope, O., Li, Q., & Wang, X. (2011). Financial reporting quality and investment efficiency of private firms in emerging markets. The Accounting Review, 86(4), 1255–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P., & Zhang, G. (2003). Heterogeneous investment opportunities in multiple-segment firms and the incremental value relevance of segment accounting data. The Accounting Review, 78, 397–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. J. (2015). Segment disclosure transparency and internal capital market efficiency: Evidence from SFAS No 131. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(4), 669–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y. J., & Seo, H. (2024). Segment dissagregation and equity-based pay contracts. Contemporary Accounting Research, 41(2), 1216–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, D., & Verrecchia, R. (1991). Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 46, 1325–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domantas, S. (2010). Practical approach to estimating cost of capital. University Library of Munich, Germany. Available online: https://econpapers.repec.org/RePEc:pra:mprapa:31011 (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Drake, P. (2010). A reading prepared by Pamela Peterson Drake. J.J Newberry. Available online: https://books.google.com.ng/books?hl=en&lr=&id=4zqgXdITQuAC&oi=fnd&pg=PR13&dq=info:05Js4eVN6N4J:scholar.google.com&ots=jh1xUDFiun&sig=2gwUrubdYYwSJpigshPZFm7MhDQ&redir_esc=y#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 23 April 2025).

- Easton, P. D. (2004). PEG ratios and estimating the implied expected rate of return on equity capital. The Accounting Review, 79(1), 73–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elberry, N. S. (2018). Corporate investment efficiency, disclosure practices and governance [Doctoral thesis, University of Portsmouth]. Available online: https://pure.port.ac.uk/ws/portalfiles/portal/13077818/Thesis.pdf (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Elsayed, N., Ammar, S., & Mardini, G. H. (2019). The impact of ERP utilization experience and segmental reporting on corporate performance in the UK context. Enterprise Information Systems, 15(1), 61–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganiyu, O. Y., Adelopo, I., Rodionova, Y., & Samuel, L. O. (2019). Capital structure and firm performance in Nigeria. African Journal of Economic Review, 7(1), 31–56. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, R., & Sidhu, B. K. (2018). The impact of mandatory international financial reporting standards adoption on investment efficiency: Standard enforcement and reporting incentives. Journal of Accounting, Finance and Business Studies, 54(3), 277–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gisbert, A., Navallas, B., & Romero, D. (2024). From IAS 14 to IFRS 8: The role of proprietary and agency costs in shaping financial reporting. Spanish Journal of Finance and Accounting/Revista Española de Financiación y Contabilidad, 53(4), 451–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L. (2000). The impact of voluntary corporate disclosures on the ex-ante cost of capital for Swiss firms. The European Accounting Review, 11(04), 741–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2006). International differences in the cost of equity capital: Do legal institutions and securities regulation matter? Journal of Accounting Research, 44(3), 485–531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hann, R. N., Ogneva, M., & Ozbas, O. (2012). Corporate diversification and the cost of capital. Journal of Finance, forthcoming, Marshall School of Business working paper No. FBE 32-09, Rock Center for Corporate Governance at Stanford University working paper No. 58, AFA 2011 Denver meetings paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1364481 (accessed on 23 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- He, J., Plumlee, M. A., & Wen, H. (2019). Voluntary disclosure, mandatory disclosure and the cost of capital. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 46(3–4), 307–335. [Google Scholar]

- Healy, P. M., & Palepu, K. G. (2001). Information asymmetry, corporate disclosure, and the capital markets: A review of the empirical disclosure literature. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 31(1-3), 405–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, O. K., & Thomas, W. B. (2008). Managerial empire building and firm disclosure. Journal of Accounting Research, 46, 591–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X., & Tarkom, A. (2022). Labor investment efficiency and cash flow volatility. Finance Research Letters, 50, 103227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IFRS 8. (2007). Operating segments. International Accounting Standards Board. Available online: https://www.ifrs.org/content/dam/ifrs/publications/pdf-standards/english/2022/issued/part-a/ifrs-8-operating-segments.pdf?bypass=on (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M. A., Yau, J. T. H., Sarang, A. A. A., Gull, A. A., & Javed, M. (2024). Information asymmetry and investment efficiency: The role of blockholders. Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 26(1), 194–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komara, A., Ghozali, I., & Januarti, I. (2020, March). Examining the firm value based on signaling theory. In 1st international conference on accounting, management and entrepreneurship (ICAMER 2019) (pp. 1–4). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lathief, J. T. A., Kumaravel, S. C., Velnadar, R., Vijayan, R. V., & Parayitam, S. (2024). Quantifying risk in investment decision-making. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(2), 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, E., & Verriest, A. (2019). Does location matter for disclosure? Evidence from geographic segments. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 46(5–6), 541–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, A. B., & Alencar, R. C. (2010). Disclosure and cost of equity capital in emerging markets: The Brazilian case. SSRN Electronic Journal, 45(4), 443–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucky, A. L. (2017). Cost of capital and corporate earning of Nigeria quoted firms: A multi-dimensional analysis of quoted firms in Nigeria. Australian Finance & Banking Review, 1(1), 41–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M. A., Zhang, X., & Umar, M. (2018). Impact of investment efficiency on cost of equity: Evidence from China. Journal of Asia Business Studies, 12(1), 44–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardini, G. H., Alkurdi, A., & Ahmed, A. H. (2023). A longitudinal investigation of IFRS-8 implementation: Evidence from Qatar. Afro-Asian Journal of Finance and Accounting, 13(1), 125–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mardini, G. H., Tahat, Y. A., & Power, D. M. (2013). Determinants of segmental disclosures: Evidence from the emerging capital market of Jordan. International Journal of Managerial and Financial Accounting, 5(3), 253–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, R. (2016). Segment disclosure practices and determinants: Evidence from Romanian listed companies. The International Journal of Management Science and Information Technology (IJMSIT), 20, 40–50. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10419/178824 (accessed on 14 August 2024).

- Meiryani, H. S., Soepriyanto, G., Jessica, F. M., Grabowska, S., & Aljuaid, M. (2023). The effect of voluntary disclosure on financial performance: Empirical study on manufacturing industry in Indonesia. PLoS ONE, 18(6), e0285720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moldovan, R. (2015). Three essays on operating segment disclosure. Essex Business School. [Google Scholar]

- Moncarz, E. S., Moncarz, R., Cabello, A., & Moncarz, B. (2006). The rise and collapse of Enron: Financial innovation, errors and lessons. Contaduría y Administración, 218, 17–37. Available online: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=39521802 (accessed on 18 April 2025).

- Nagar, V., Nanda, D., & Wysocki, P. (2003). Discretionary Disclosure and Stock-Based Incentives. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 34, 283–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odia, J. O. (2018). The determinants and decision usefulness of ifrs 8 on segment disclosures. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/THE-DETERMINANTS-AND-DECISION-USEFULNESS-OF-IFRS-8-OdiaJ./1cdbce0d8a641d1e36a556794db13196b0dfd99c (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Opara, S. (2017, March 5). 15 firms delisted from Nigerian stock exchange in 2016. Punch Newspaper. Available online: https://punchng.com/15-firms-delisted-from-nigerian-stock-exchange-in-2016-report/#google_vignette (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Owusu-Ansah, S. (1998). The impact of corporate attributes on the extent of mandatory disclosure and reporting by listed companies in Zimbabwe. The International Journal of Accounting, 33(5), 605–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peláez, B. B. (2010). Segment disclosure, cost of capital and investment efficiency [Doctoral thesis, Department de economica de la empressa, Universidad, Carloss III de Madrid]. Available online: https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/rest/api/core/bitstreams/c63f74d2-63b4-4294-a19c-2a9fa4f4dc4b/content (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Prencipe, A. (2004). Proprietary costs and voluntary segment disclosure: Evidence from Italian listed companies. European Accounting Review, 13(2), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffournier, B. (1995). The determinants of voluntary financial disclosure by Swiss listed companies. The European Accounting Review, 4, 261–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Revsine, L., Collins, D., & Johnson, B. (1999). Financial reporting and analysis. Prentice Hall International. Available online: https://books.google.co.za/books/about/Financial_Reporting_and_Analysis.html?id=soEeAQAAIAAJ&redir_esc=y (accessed on 11 September 2024).

- Saini, J. S. (2010). Cost of equity capital, information asymmetry, and segment disclosures [Doctoral thesis, Oklahoma State University]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwarcz, S. L. (2023, April). Reexamining Enron’s regulatory consequences. NYU annual survey of American law, 2023, Duke Law School public law & legal theory series No. 2023-28. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4419119 (accessed on 12 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Serghiescu, L., & Văidean, V. L. (2014). Determinant factors of the capital structure of a firm: An empirical analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 15, 1447–1457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shehata, N. F. (2014). Theories and determinants of voluntary disclosure. Accounting and Finance Research, 3(1), 18–26. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2442486 (accessed on 12 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Shittu, I., & Che-Ahmad, A. (2024). Corporate governance and equity value: Empirical evidence from Nigerian firms. Corporate Governance, 24(2), 462–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sule, D. F. (2025a). Can segment disclosure improve the investment efficiency of listed companies in Nigeria? African Journal of Business and Economic Research, 20(1), 319–340. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_ajber_v20_n1_a14 (accessed on 19 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Sule, D. F. (2025b). The determinants off voluntary segment disclosure by Nigerian Listed Companies: Further Evidence. African Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 4(1), 311–329. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-aa_ajie_v4_n1_a13 (accessed on 19 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Svetek, M. (2022). Signaling in the context of early-stage equity financing: Review and directions. Venture Capital, 24(1), 71–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uremadu, S. F., & Onyekachi, O. (2019). The impact of capital structure on corporate performance in Nigeria: A quantitative study of the consumer goods sector. Current Investigations in Agriculture and Current Research, 5(4), 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F., Zhu, Z., & Hoffmire, J. (2015). Financial reporting quality, free cash flow and investment efficiency. EDP Sciences, SHS Web Conferences, 17, 701027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahaya, O. A. (2024). Board characteristics and cost of capital of listed consumer goods companies in Nigeria. SSRN. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=5028900 (accessed on 11 October 2024). [CrossRef]

- Yasar, B., Martin, T., & Kiessling, T. (2020). An empirical test of signaling theory. Management Research Review, 43(11), 1309–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Measurement | References |

|---|---|---|

| TSD | A total segment disclosure index of 42 adapted from extant studies 1(0) if segment information is (is not) disclosed | Mardini et al. (2013) and Blanco et al. (2015) |

| Investment efficiency ( | Biddle et al. (2009), Wang et al. (2015), and F. Chen et al. (2011) | |

| Cost of capital | PEG ratio =

| Easton (2004) |

| Size | Hail and Leuz (2006), Diamond and Verrecchia (1991), Wang et al. (2015) | |

| Book-to-market ratio | Hail and Leuz (2006); Wang et al. (2015). | |

| Growth | Nagar et al. (2003). | |

| Tangibility | Serghiescu and Văidean (2014) | |

| Cash flow | Biddle et al. (2009), Wang et al. (2015) | |

| Profitability | Raffournier (1995) |

| TSD | CoC | INV_EFF | MTB | TANG | CASHFL | GROWTH | PROF | AGE | SIZE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 18.18 | 2.61 | 0.35 | 0.88 | 0.29 | 1.42 | 0.39 | 1.64 | 23.70 | 18.78 |

| Median | 18.00 | 2.48 | 0.33 | 0.70 | 0.27 | 1.27 | 0.41 | 1.35 | 23.00 | 15.60 |

| Maximum | 24.00 | 23.58 | 0.47 | 3.45 | 0.46 | 1.90 | 0.71 | 4.88 | 60.00 | 35.50 |

| Minimum | 13.00 | 0.02 | 0.07 | 0.20 | 0.15 | 1.18 | 0.23 | 0.99 | 1.00 | 5.76 |

| Std. Dev. | 2.28 | 1.82 | 0.07 | 0.49 | 0.08 | 0.26 | 0.08 | 0.82 | 14.24 | 9.41 |

| Skewness | 0.45 | 2.26 | 0.04 | 0.87 | 0.01 | 0.76 | 0.51 | 2.29 | 0.29 | 0.42 |

| Kurtosis | 2.76 | 24.23 | 3.26 | 4.24 | 2.10 | 2.04 | 4.44 | 8.00 | 1.98 | 1.75 |

| Sum | 12,366.0 | 1780.39 | 228.96 | 601.78 | 200.41 | 965.36 | 269.63 | 1121.63 | 16116.00 | 12,770.59 |

| Observations | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 | 680 |

| VIF | INV_EFF | CoC | PROF | SIZE | GROWTH | TANG | MTB | CASHFL | TSD | AGE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| INV_EFF | - | 1.00 | |||||||||

| CoC | 2.02 | −0.24 ** | 1.00 | ||||||||

| PROF | 1.12 | 0.13 * | −0.05 | 1.00 | |||||||

| SIZE | 1.11 | 0.02 | 0.02 * | 0.12 * | 1.00 | ||||||

| GROWTH | 1.21 | 0.05 ** | −0.00 | −0.02 | −0.05 ** | 1.00 | |||||

| TANG | 1.16 | 0.02 ** | 0.06 ** | −0.05 ** | −0.04 | −0.05 * | 1.00 | ||||

| MTB | 2.51 | 0.06 * | −0.09 | 0.08 | −0.02 | −0.00 | −0.07 * | 1.00 | |||

| CASHFL | 2.09 | 0.26 ** | −0.18 ** | 0.18 ** | −0.06 ** | −0.00 | 0.00 | 0.08 ** | 1.00 | ||

| TSD | 1.22 | 0.15 *** | 0.13 * | 0.08 | −0.06 | 0.07 ** | 0.03 * | 0.05 | 0.03 | 1.00 | |

| AGE | 1.06 | 0.01 | −0.01 | −0.18 | 0.01 ** | 0.02 * | −0.05 | −0.03 * | −0.19 ** | 0.01 | 1.00 |

| Variables | Pooled OLS | Fixed Effect | Random Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| CoC | −0.0250 (0.0965) *** | 0.0289 (0.3435) | −0.0267 (0.0307) ** |

| TSD | 0.0192 (0.0089) * | 0.0114 (0.0908) *** | 0.0119 (0.0303) ** |

| TSD*COC | 0.0215 (0.0078) * | 0.0141 (0.0894) *** | 0.0192 (0.0030) * |

| LOG(PROF) | 0.0099 (0.8131) | −0.0165 (0.0097) * | −0.0126 (0.0001) * |

| LOG(SIZE) | −0.0036 (0.1990) | 0.0075 (0.1244) | 0.0042 (0.0835) *** |

| GROWTH | 0.0439 (0.0129) ** | 0.0247 (0.0199) *** | 0.0258 (0.0272) ** |

| TANG | 0.0360 (0.0299) ** | −0.0289 (0.2935) | −0.0257 (0.2539) |

| MTB | 0.0059 (0.0464) ** | 0.0036 (0.1466) | 0.0035 (0.2583) |

| CASHFL | 0.0565 (0.0000) * | 0.0793 (0.0076) * | 0.0803 (0.0016) * |

| LOG(AGE) | 0.0004 (0.8266) | 0.013773 (0.00117) | 0.009668 (0.0571) *** |

| C | 0.1858 (0.0000) * | 0.1352 (0.0563) ** | 0.1517 (0.0051) * |

| R-square | 0.1318 | 0.8143 | 0.8590 |

| Adjusted R-square | 0.1201 | 0.7849 | 0.7370 |

| Hausman | 7.567 (0.865) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sule, D.F.; Moloi, T. How Do Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital Impact the Investment Efficiency of Listed Firms in Nigeria? J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050258

Sule DF, Moloi T. How Do Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital Impact the Investment Efficiency of Listed Firms in Nigeria? Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050258

Chicago/Turabian StyleSule, Dolapo Faith, and Tankiso Moloi. 2025. "How Do Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital Impact the Investment Efficiency of Listed Firms in Nigeria?" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050258

APA StyleSule, D. F., & Moloi, T. (2025). How Do Segment Disclosure and Cost of Capital Impact the Investment Efficiency of Listed Firms in Nigeria? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050258