1. Introduction

PayLater is a digital payment platform that aims to offer users a convenient and efficient way to handle their financial transactions. As the demand for quick, secure, and practical payment systems grows, PayLater meets these needs by providing features that streamline payments, financial management, and everyday transactions. With ongoing advancements in information technology fueling the expansion of digital financial services, PayLater is in line with the global shift towards a cashless society, where digital payments are viewed as safer and more efficient than traditional methods (

Arvidsson, 2019). Additionally, PayLater presents unique advantages for consumers with irregular income, improving financial flexibility and cash flow management. By enabling users to postpone payments and make purchases even when funds are temporarily low, it helps to bridge the gap caused by income fluctuations. Users can also modify payment options after transactions are completed, showcasing the flexibility and convenience of the “buy now, pay later” model (

Brune et al., 2021).

In Indonesia, the adoption of PayLater services has surged in recent years due to economic challenges and changing consumer behaviors. Economic downturns have diminished household purchasing power, pushing many to rely on PayLater as a convenient solution for managing expenses (

Ramli & Setiawan, 2024). These services, particularly popular among young and middle-income groups, have witnessed rapid growth, with platforms like Gojek, Shopee PayLater, and Kredivo leading the market. The increasing number of PayLater financing contracts in Indonesia (

Figure 1: Number of PayLater Financing Contracts in Indonesia) reflects this growing reliance on deferred payment options. However, this growth has not come without challenges. High-profile data breaches, such as the Indonesian Communication and Informatics Service incident in 2024, which exposed sensitive personal information, have heightened public concerns over data security and cyber fraud (

Revolusi, 2024). These challenges highlight a crucial paradox; while PayLater services provide financial flexibility and convenience, persistent trust issues continue to shape consumer adoption.

PayLater adoption in Malaysia has grown rapidly, surpassing 5 million users in 2023, driven by providers like Atome, Grab, PayLater, and Rely. Millennials and Gen Z are the primary users, especially for small purchases like electronics, fashion, and daily essentials (

Research and Markets, 2025). The rising demand is fueled by limited credit card penetration and a booming e-commerce market, positioning PayLater as a mainstream payment method, with expected innovations such as loyalty programs and digital wallet integrations. However, concerns over data security and the risks of digital financial tools have slowed adoption (

Samarasekara et al., 2023). At the same time, Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) has tightened regulations to prevent consumer debt and improve transparency, following similar moves in Singapore and Australia. While stricter credit assessments and clearer disclosures may build trust, they could also push smaller providers out of the market (

Malay Mail, 2025). In both Malaysia and Indonesia, PayLater adoption is hindered by security concerns and regulatory challenges. To encourage growth, fintech companies must strengthen cybersecurity, improve transparency, and educate consumers to build trust and ensure a safer financial ecosystem in Southeast Asia.

Although extensive research has been conducted on fintech adoption, the influence of trust and security on PayLater usage remains underexplored, particularly in Southeast Asia. Existing studies have primarily examined factors such as convenience and impulse buying behavior. For example, prior research has analyzed PayLater adoption from an Islamic economic perspective, investigating its impact on impulse buying and consumer behavior in Indonesia (

Khairunnisa et al., 2022). Similarly, a study on Generation Z in Malaysia found that materialism, money management skills, self-efficacy, attitude, subjective norms, perceived behavioral control, and moral obligation significantly influence the intention to adopt PayLater services (

Osman et al., 2024). While these studies provide valuable insights, they largely overlook the crucial role of trust and security concerns in shaping consumer decision making.

Furthermore, while fintech adoption has been widely studied on a global scale, much of the existing literature focuses on Western economies or China, where digital financial ecosystems are more developed. Research from the U.S. and Europe highlights the importance of regulatory frameworks and consumer protection in fostering trust; whereas, studies from China emphasize the role of super-app ecosystems in driving adoption. In contrast, Southeast Asian markets, such as Indonesia and Malaysia, present distinct regulatory landscapes, varying levels of digital literacy, and unique consumer perceptions of financial risk. This study aims to bridge this research gap by conducting a comparative analysis of trust and security concerns in PayLater adoption within these two neighboring yet distinct fintech environments.

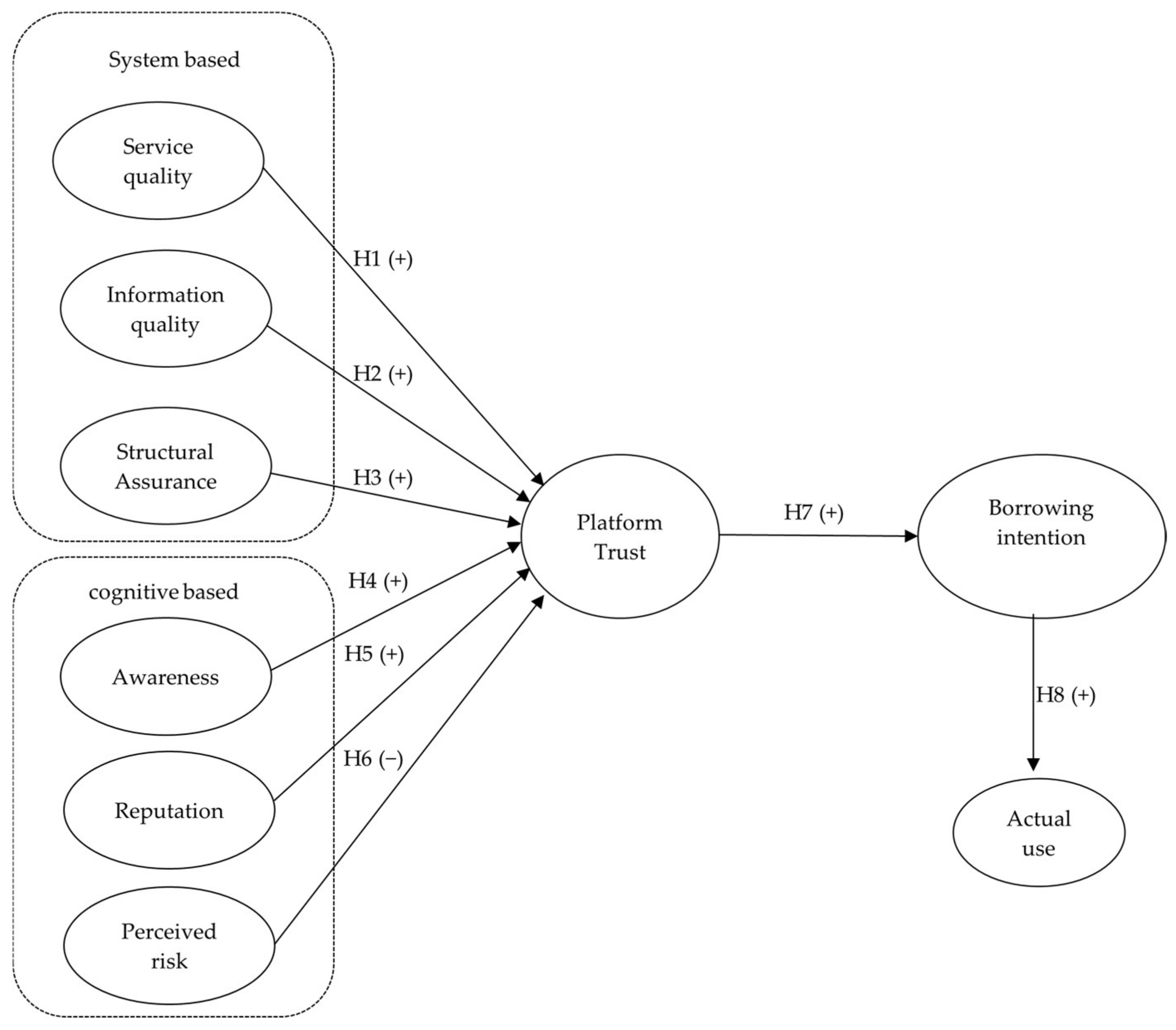

To address these research gaps, this study investigates the determinants of PayLater adoption in Southeast Asia, with a specific focus on the role of trust and security in Indonesia and Malaysia. Drawing from established models, like the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the diffusion of innovations theory, which emphasize perceived ease of use and usefulness in technology adoption (

Davis, 1989;

Rogers, 2003), this research extends TAM by integrating platform trust as a key factor. It explores how trust and security concerns shape adoption, what drives differences in consumer trust between the two countries, and how system-based factors (such as service quality, information quality, and structured assurance) and cognitive-based factors (such as awareness, reputation, and risk perception) influence user behavior. By adopting this expanded framework, the study provides a more comprehensive understanding of trust in digital financial platforms. Additionally, this study situates its findings within a broader global context by comparing trends in Indonesia and Malaysia to those observed in other regions where PayLater adoption has been extensively studied.

This research contributes to the literature by refining theoretical frameworks on fintech adoption and expanding the application of TAM in the context of digital lending. By incorporating trust dimensions as a central construct, it provides a comprehensive framework to analyze consumer decision making in emerging fintech markets. Practically, the findings offer actionable recommendations for fintech companies and regulators, emphasizing strategies such as enhanced cybersecurity measures, transparent communication, and consumer education initiatives to build trust and improve user adoption. By examining PayLater adoption through a comparative lens, this research not only deepens the understanding of Southeast Asian fintech markets but also provides broader insights applicable to emerging economies facing similar trust-related barriers in digital finance.

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

2.1. The Influence of Service Quality on Platform Trust

Service quality refers to the extent to which a service meets or exceeds customer expectations, playing a crucial role in customer satisfaction and long-term loyalty. According to the SERVQUAL model (

Sari et al., 2023), service quality is assessed through the following five key dimensions: tangibility, reliability, responsiveness, assurance, and empathy. In the digital context, these aspects become even more critical due to the lack of physical interaction, making responsive service, secure transactions, and service reliability essential for user satisfaction (

Wang & Huang, 2025).

Platform trust is the users’ confidence that a platform will provide secure and reliable services.

Mayer et al. (

1995) identify the following three core components of trust: ability (competence), benevolence (concern for users), and integrity (honesty). Research indicates that high service quality strengthens users’ trust in digital platforms (

McKnight et al., 2002). Factors such as quick responsiveness, transaction security, and effective customer support contribute to enhancing user trust (

Gefen et al., 2003;

Kim & Yum, 2024).

In conclusion, service quality and platform trust are deeply interconnected. High service quality enhances user experience and strengthens their trust in digital platforms. Therefore, digital businesses must ensure responsive, reliable, and secure services to maintain user loyalty and competitiveness in the digital marketplace.

H1. Service quality positively influences platform trust.

2.2. The Influence of Information Quality on Platform Trust

Information quality is a crucial factor in information systems and digital marketing, covering aspects such as accuracy, relevance, completeness, timeliness, and clarity. High-quality information enhances user decision making, engagement, and trust in digital platforms (

van der Cruijsen et al., 2023). Beyond accuracy, the way information is structured and presented also plays a key role in shaping user perceptions and fostering trust (

Xu et al., 2013).

Trust is essential for user interactions on digital platforms, especially in e-commerce. Users’ trust is closely tied to the reliability and transparency of the information provided (

Gefen et al., 2003). Research shows that up-to-date, well-structured, and clearly presented information significantly boosts user trust and engagement (

Kim & Yum, 2024;

McKnight et al., 2002;

Wu et al., 2022).

Moreover, information quality is critical for user retention and long-term engagement. Platforms that fail to provide reliable information risk losing user trust and loyalty (

Cheng et al., 2024). As digital reliance grows, prioritizing accuracy, relevance, and transparency in information delivery is key to building trust, enhancing user satisfaction, and ensuring long-term platform success.

H2. Information quality has a significant positive influence on platform trust.

2.3. The Influence of Structured Assurance on Platform Trust

Structured assurance refers to the institutional and technological measures put in place to build user confidence in a platform’s reliability and security (

Y. Yang et al., 2024). This concept encompasses various components, including compliance with regulations, data protection protocols, and clear operational procedures (

Manghani, 2011). In the context of digital payment systems, structured assurance is crucial for establishing user trust, especially in platforms that offer deferred payment options, like PayLater services. These services, which allow consumers to postpone payments, inherently carry a certain level of risk (

Jafri et al., 2024). Consequently, structured assurance mechanisms are vital in shaping users’ perceptions of the platform’s trustworthiness and security.

The structured assurance case metamodel (SACM) serves as a theoretical framework for understanding and implementing structured assurance in digital platforms. Developed by the object management group (OMG), SACM provides a standardized method for documenting and presenting claims, arguments, and evidence that demonstrate a system’s reliability and security. In the case of PayLater platforms, SACM can be employed to systematically detail the platform’s security measures and operational protocols, providing users with a transparent and verifiable assurance case. This transparency aligns with SACM’s goal of fostering confidence through auditable claims and evidence, addressing essential trust factors, such as security, fairness, and transparency (

Wei et al., 2019).

Applying SACM principles in PayLater platforms enhances structured assurance by presenting concrete evidence of compliance with industry standards, such as data encryption, multi-factor authentication, and fraud detection systems. Certifications from reputable third-party security organizations further reinforce structured assurance by providing tangible proof of adherence to rigorous security and privacy standards (

Alzaidi & Agag, 2022). By documenting these security measures using SACM, PayLater platforms can effectively communicate their commitment to protecting user data and minimizing risks of fraud or breaches (

Chatterjee et al., 2024).

Furthermore, SACM underscores the importance of clear reasoning in assurance cases, allowing platforms to illustrate how specific security measures mitigate perceived risks. This is particularly crucial for PayLater services, where financial commitments are deferred, heightening user concerns about security and fairness. Therefore, structured assurances, such as encryption, third-party certifications, and transparent compliance with regulatory standards, are expected to positively impact trust in PayLater platforms. By adopting SACM principles, PayLater providers can move beyond merely implementing security measures to actively demonstrating their effectiveness, ultimately fostering greater trust and encouraging wider user adoption.

H3. Structured assurance has a positive effect on platform trust.

2.4. The Influence of Awareness on Platform Trust

Awareness, in the context of digital platforms, refers to how well users understand the features, benefits, and risks associated with a service (

A. George & Gireeshkumar, 2013). This understanding aligns with the hierarchy of effects theory, which posits that awareness is the initial stage in the decision making process, laying the groundwork for subsequent user behaviors, like evaluation, trial, and adoption. Awareness includes not just knowledge of the platform itself but also an understanding of the mechanisms that ensure user safety and security. This concept is especially important in financial services, particularly for PayLater platforms, where users must navigate the complexities of deferred payment options. According to the diffusion of innovations theory, awareness is a crucial factor in adopting new technologies, as users need to be exposed to and comprehend the innovation before moving toward adoption (

Rogers, 2003). In this context, greater awareness can significantly shape users’ perceptions of trust and their willingness to engage with these platforms (

Daneshgadeh & Yıldırım, 2014).

In digital platforms that involve sensitive financial transactions, such as PayLater services, awareness is essential in building users’ trust. Drawing from the technology acceptance model (TAM), perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use are key factors that affect technology adoption. Awareness boosts these perceptions by informing users about the platform’s security measures, including encryption protocols, fraud detection systems, and data privacy policies. Users who are aware of these features are more likely to view the platform as trustworthy (

Saeed, 2023). This is because increased awareness diminishes uncertainties and reassures users that their personal and financial information is secure. Furthermore, in line with the hierarchy of effects theory, being aware of a platform’s security certifications and compliance with industry standards boosts users’ confidence by offering concrete proof of reliability (

Culot et al., 2021). This awareness not only builds trust but also aids in the overall process of adopting new technology.

In conclusion, awareness serves as a crucial foundation in both the technology acceptance model and the diffusion of innovations theory, connecting knowledge and trust. It is suggested that greater user awareness regarding a platform’s security, transparency, and operational practices will positively impact trust in the platform, ultimately encouraging adoption and ongoing use.

H4. Awareness has a positive effect on platform trust.

2.5. The Influence of Reputation on Platform Trust

The reputation of companies in the financial sector plays a crucial role in establishing trust, especially for new consumers who lack prior experience with the platform. Reputation is often used as a primary indicator of a service’s reliability and security. According to

Kaabachi et al. (

2017), consumers without personal experience with a platform typically rely on the available information about its reputation to reduce uncertainty when making decisions. Referring to signaling theory (

Spence, 1973), provider reputation is important information used by consumers to form and maintain a level of trust, so that they are willing to put themselves in a vulnerable position by using a relatively new product (

Garrouch, 2021). A strong reputation serves as a positive signal, reassuring consumers that the platform can be trusted, while also mitigating perceived risks (

Qalati et al., 2021).

In the context of fintech, where new technologies and innovations are frequently introduced, reputation becomes even more vital. Consumers who are unfamiliar with fintech services may feel skeptical about the security and reliability of such platforms. However, a solid reputation can help address these concerns, reassuring consumers that the platform is secure and trustworthy (

Nguyen et al., 2022). Thus, a strong reputation not only influences initial consumer trust but also promotes the adoption of new technologies in financial services. Previous studies consistently demonstrate that reputation positively impacts trust in a platform (

Cardoso & Cardoso, 2024;

Garrouch, 2021;

Jadil et al., 2022). Therefore, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H5. Reputation has a positive effect on platform trust.

2.6. The Influence of Risk Perception on Platform Trust

Risk perception plays a significant role in shaping consumer trust when using financial services. In this context, risk perception refers to an individual’s assessment of the potential losses that may arise from using financial services, including the loss of money, data breaches, or other risks associated with financial transactions. According to consumer perceived risk theory, consumers perceive risk, because they face uncertainty and possible unintended consequences as a result of using financial services (

Mitchell, 1992). Perceived risk is powerful in explaining consumer behavior, because consumers are more often more motivated to avoid mistakes than to maximize utility in using PayLater services (

Mitchell, 1999). When consumers perceive high risks related to a financial service, they tend to be more cautious and skeptical, which can lower their trust in the service provider. Consumers with high-risk perceptions are more likely to seek additional information and demand greater transparency from service providers. If providers fail to offer sufficient assurances regarding the security and reliability of their services, consumer trust will decline (

Eastlick et al., 2006).

In the fintech context, risk perception significantly affects the adoption of fintech services. This research emphasizes the importance for fintech companies to address high-risk perceptions to enhance consumer trust. Therefore, fintech companies that effectively manage risk perception are more likely to succeed in attracting and retaining customers. Customers with higher trust tendencies perceive lower risks and are, thus, more confident in engaging in online transactions (

Agag & Eid, 2019). Previous studies have found that risk perception negatively affects platform trust (

Chen et al., 2015;

Q. Yang & Lee, 2016).

H6. Risk perception has a negative effect on platform trust.

2.7. The Influence of Platform Trust on Borrowing Intention

Trust is a complex concept that can be defined in many ways (

Castaldo et al., 2010); it can encompass reliance, belief, willingness, expectation, confidence, and attitude. In the realm of business relationships, trust is characterized by the interaction between a trustor and a trustee, which can include individuals, groups, firms, or organizations. These entities are often evaluated based on qualities such as competence, expertise, honesty, integrity, and benevolence, which are essential for building trust. Essentially, trust allows individuals to make future decisions informed by past experiences and has been studied across various fields, including social psychology, e-commerce, and e-banking. Over time, the concept of trust has shifted from being mainly interpersonal to incorporating mechanisms based on platforms (

Szabó, 2024).

Trust plays a crucial role in shaping consumer behavior, particularly in the context of financial transactions facilitated by digital platforms. In the context of digital financial transactions, consumer behavior can manifest as the intention to borrow through PayLater services. Borrowing intention refers to the extent to which users consciously formulate plans to use the PayLater services provided on a platform (

Hooda et al., 2022). Research by

Nur and Azzahra (

2023) indicates that the intention to borrow via PayLater services is influenced by the level of trust users have in the platform. Other studies also highlight that users’ intention to use PayLater services is influenced by various behavioral and psychological factors, including their trust in the service, which significantly impacts their willingness to engage with PayLater (

Fitriyah & Nadlifatin, 2024;

Szabó, 2024).

H7. Platform trust has a positive effect on borrowing intention.

2.8. The Influence of Borrowing Intention on Actual Use

Borrowing intention reflects the user’s desire or intention to utilize the borrowing facilities offered by PayLater services. The elements within users’ intentions have a significant impact on their actual usage of a platform (

Pan et al., 2024). When the intention to borrow is high, it is likely to contribute to increased actual use, which refers to the actualization of using PayLater services for transactions.

The concept of actual use on a service platform refers to the frequency of users utilizing the service and an estimate of how many times they engage in that service within a certain period (

Shamsuzzoha et al., 2023). Several factors can influence users’ actual use of a service, one of which is borrowing intention, or the user’s intention to borrow money through PayLater services. There is a strong relationship between borrowing intention (the intention to borrow) and actual use (the real-world usage). One study has shown that behavioral intention, defined as the perceived or subjective probability that an individual will engage in a specific behavior, significantly affects the actual use of a service (

Azzahra et al., 2023).

H8. Borrowing intention has a positive effect on actual use.

Based on the literature review and hypothesis development, we propose the research model in

Figure 2.

3. Research Methods

This study aims to analyze the factors (system-based and cognitive-based) that influence trust in platforms, examine how this trust impacts borrowing intentions, and explore the relationship between borrowing intentions and actual usage. A quantitative research approach is employed, utilizing non-probability purposive sampling to ensure the selection of relevant respondents. This method was chosen, because the study specifically targets active PayLater users, defined as individuals who have used PayLater services multiple times within the past three months, those who are unable to make immediate payments, and users who manage PayLater accounts for their financial needs. By selecting respondents who meet these criteria, purposive sampling allows for a more focused and relevant analysis of the challenges faced by PayLater users and the factors influencing their trust in such platforms. However, this sampling technique has limitations, as findings cannot be generalized to individuals who use fintech payment services but do not utilize PayLater specifically.

The research instrument, a structured questionnaire, was developed based on an extensive review of prior studies on platform trust, borrowing intentions, and actual usage behavior. The selection of constructs was guided by established theoretical frameworks, including the technology acceptance model (TAM) and the diffusion of innovations theory. The questionnaire consists of 41 items organized into four sections. The first section collects demographic information to provide insights into respondent characteristics. The second section assesses platform trust factors, including perceived security, perceived transparency, and prior experience. The third section evaluates borrowing intentions, while the final section measures the frequency and manner in which users engage with PayLater services. Details of the questionnaire in this study are in

Appendix A.

To ensure content validity, the questionnaire was pre-tested with a small group of PayLater users, and their feedback was incorporated into the final version. Additionally, fintech experts and academic researchers specializing in consumer behavior and digital finance reviewed the instrument to enhance its reliability and relevance. Data collection took place online between August and September 2024, targeting PayLater users in Indonesia and Malaysia to allow for a comparative analysis. A total of 246 responses were collected, comprising 106 from Indonesia (62 active PayLater users) and 140 from Malaysia (85 active users). While the sample sizes are relatively small, they align with prior re-search on fintech adoption within specific user groups. Nonetheless, the study acknowledges potential limitations in sample representativeness and recommends future research with larger and more diverse populations to enhance generalizability.

To analyze the data and test the proposed hypotheses, partial least squares structural equation modeling (PLS-SEM) was employed using SmartPLS software version 3.2.9. This method was selected, because it is particularly effective in examining complex, multi-variable relationships, accommodating smaller sample sizes, and allowing for the predictive modeling of latent constructs, such as trust and borrowing intentions, which are difficult to measure directly. To ensure the robustness of the model, reliability and validity tests were con-ducted. Composite reliability (CR) and Cronbach’s alpha were used to assess internal consistency, with acceptable thresholds set above 0.7. Convergent validity was evaluated using average variance extracted (AVE), requiring values above 0.5, while discriminant validity was tested using the Fornell–Larcker criterion. These assessments confirm that the measurement model is statistically sound and that the constructs used in the study are both reliable and valid.

By employing this methodological approach, the study ensures a structured and rigorous analysis of trust in PayLater services, offering insights into its impact on borrowing behavior and actual usage.

4. Results

The results for the outer model, which examines the relationship between variables and their indicators, are assessed by looking at the factor loading values. The validity is considered sufficient if the factor loading values exceed 0.7. Factor loading represents the correlation between an indicator and its respective variable; if it is above 0.7, it is considered valid (

Hair et al., 2019). For the Indonesian sample, after eliminating indicators that have a factor loading below 0.7, the remaining indicators have met the validity and reliability criteria. In the Malaysian sample, one indicator from the reputation variable was dropped, but after re-testing, the factor loadings for all indicators exceeded 0.7, thereby ensuring the validity of the Malaysian sample as well. The loading factor for each indicator can be seen in

Appendix B.

To confirm the robustness of the model, the R-square values serve as indicators of the explanatory power of the independent variables in predicting the dependent variables, as presented in

Table 1.

For the Indonesian sample,

Table 1 shows that the R-square value of 0.626 indicates that 62.6% of the variability in actual use is explained by borrowing intention, demonstrating a strong predictive relationship. Similarly, 18.3% of the variability in borrowing intention is accounted for by platform trust, suggesting a moderate explanatory power. Furthermore, 78.1% of the variability in platform trust is explained by cognitive-based and system-based factors, highlighting the model’s robustness in capturing the key determinants of trust.

For the Malaysian sample,

Table 1 reports an R-square value of 0.516, suggesting that 51.6% of the variability in actual use is explained by borrowing intention, confirming a substantial influence. The R-square value of 0.468 indicates that 46.8% of the variability in borrowing intention is attributed to platform trust, reinforcing its role in shaping borrowing behavior. Additionally, cognitive-based and system-based factors explain 77.9% of the variability in platform trust, as reflected in the R-square value of 0.779, further supporting the model’s robustness. These findings, as summarized in

Table 1, confirm the model’s ability to effectively capture the relationships among platform trust, borrowing intention, and actual use across both countries, reinforcing the reliability of the results.

Discriminant validity was tested by comparing the square root of the average variance extracted (AVE) with the correlations between variables. Discriminant validity is considered met if the square root of the AVE is greater than the correlations with other variables. The results show that, for all variables, the square root of the AVE exceeded the correlations with other variables, indicating that discriminant validity is satisfied. Next, the measurement model was assessed by looking at the average variance extracted (AVE). If the AVE value is greater than 0.5, it indicates good convergent validity for the latent variables. The test results showed that the AVE for all variables was greater than 0.5, confirming that the validity requirements were met. Reliability was assessed using composite reliability, with a threshold of 0.70 indicating that the indicators consistently measure their respective latent variables. The results showed that all variables had composite reliability values above 0.70, indicating that the constructs are reliable.

The results of testing the relationship between variables are shown in

Table 2 for the Indonesian sample and

Table 3 for the Malaysian sample.

The results from the inner model indicate differences between Indonesia and Malaysia regarding the factors influencing platform trust. In Indonesia, the factors influencing platform trust are structured assurance and reputation. In contrast, in Malaysia, the factors influencing platform trust include information quality, reputation, and perceived risk. However, platform trust significantly influences borrowing intention in both countries. Additionally, the effect of borrowing intention on actual use is significant and similar in both Indonesia and Malaysia.

5. Discussion

The results from the analysis provide valuable insights into the factors influencing platform trust and how platform trust affects borrowing intention and actual use of PayLater services, revealing both similarities and differences between Indonesian and Malaysian respondents. The findings highlight the complex nature of consumer behavior within the digital financial services space and underscore the importance of localizing strategies to enhance platform trust and foster platform usage.

5.1. Factors Influencing Trust

This study examined key factors influencing platform trust in PayLater services across Indonesia and Malaysia, revealing notable differences in consumer trust formation. While some hypotheses were supported, others were rejected, offering insights into the role of service characteristics, regulatory environments, and consumer behaviors in shaping trust in digital financial services.

5.1.1. H1: Service Quality and Platform Trust

The impact of service quality on platform trust was found to be insignificant in both Indonesia and Malaysia. This can be attributed to the standardized nature of PayLater services, where ease of application, seamless processing, and flexible payment options are already well-established. Since all transactions are conducted online without the need for physical interaction, factors such as data security, platform reputation, and prior user experience play a more critical role in shaping trust. Prior studies suggest that, while high service quality enhances user satisfaction, trust in digital financial services is primarily influenced by perceived risk, transparency, and consistency in user experience (

Gefen et al., 2003). Additionally, trust is a long-term construct that evolves over time, rather than being determined by any single aspect of service delivery. Consequently, users prioritize security and long-term reliability over immediate service quality, leading to the non-significant relationship between service quality and platform trust.

5.1.2. H2: Information Quality and Platform Trust

Information quality did not significantly influence platform trust in Indonesia, likely because PayLater services in the country, such as Shopee PayLater, GoPay PayLater, Kredivo, OVO PayLater, and Traveloka PayLater, provide relatively uniform information. Since loan limits, installment tenures (typically up to 12 months), and interest rates (ranging from 2.2% to 4.8%) are similar across platforms, users may not consider information quality as a differentiating factor in trust formation. Instead, when facing urgent needs, they may prioritize access to credit over detailed financial disclosures.

In contrast, information quality significantly influenced platform trust in Malaysia. This difference may stem from the unique PayLater service structures in Malaysia, where platforms do not charge interest but impose late fees. For example, TikTok PayLater allows users to purchase products through installment plans without interest, making the transparency of terms a crucial factor in consumer trust. The findings align with previous research suggesting that, in markets where financial policies vary significantly, clear and accurate information can enhance trust (

Kim & Yum, 2024).

5.1.3. H3: Structured Assurance and Platform Trust

Structured assurance was a significant determinant of platform trust in Indonesia but not in Malaysia. In Indonesia, PayLater services must be registered with the Financial Services Authority (Otoritas Jasa Keuangan, OJK) to operate legally. The OJK enforces compliance with regulations to ensure fair and transparent operations, protect consumers from fraudulent practices, and enhance data security. Given that PayLater services have been available in Indonesia since 2019, consumers have had time to develop trust in regulatory oversight. This finding supports the argument that institutional assurances play a key role in digital trust formation, particularly in markets where financial technology is well-established (

Y. Yang et al., 2024).

Conversely, structured assurance did not significantly influence trust in Malaysia, possibly because PayLater services were introduced more recently. While Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM) oversees fintech services, the market is still evolving, with newer platforms such as TikTok PayLater only launching in 2024. As a result, Malaysian users may not yet perceive regulatory oversight as a key trust factor and instead rely more on direct user experiences and platform reputation.

5.1.4. H4: Awareness and Platform Trust

Awareness did not significantly influence platform trust in either Indonesia or Malaysia. Since the respondents were already active PayLater users, they were familiar with the platforms, their risks, and the regulatory bodies overseeing them—OJK in Indonesia and BNM in Malaysia. Awareness, therefore, did not necessarily translate into increased trust. This result is different from the findings of

Q. Yang and Lee (

2016).

5.1.5. H5: Reputation and Platform Trust

Reputation significantly influenced platform trust in both Indonesia and Malaysia. The results of this study are in accordance with

Cardoso and Cardoso (

2024) and

Garrouch (

2021). A strong reputation for honesty and reliability enhances user confidence in PayLater services. If platforms demonstrate a commitment to customer service, such as resolving complaints efficiently, ensuring fast approval processes, and transparently communicating fees, interest rates, and terms, users are more likely to trust them. Reputation serves as a crucial signal of platform integrity, aligning with digital trust theories that emphasize credibility in online transactions (

Mayer et al., 1995). A well-managed reputation not only fosters trust but also increases user loyalty and long-term engagement with the platform.

5.1.6. H6: Perceived Risk and Platform Trust

The influence of perceived risk on platform trust differed between Indonesia and Malaysia. In Indonesia, perceived risk did not significantly affect trust, suggesting that users’ decisions to utilize PayLater services were driven more by financial necessity or habitual credit use rather than concerns about security or potential financial loss. Many users, particularly students, rely on credit-based purchasing due to limited savings, making them less sensitive to risk. Optimism bias may also play a role, where users assume they will be able to manage installment payments without considering potential financial difficulties. In contrast, perceived risk significantly influenced platform trust in Malaysia. Unlike in Indonesia, Malaysian PayLater services impose late fees instead of interest rates, leading users to perceive different financial risks. Concerns over unexpected penalties or financial losses contribute to lower trust levels among Malaysian users. This finding aligns with prior studies indicating that, in digital financial services, perceived financial uncertainties can reduce consumer trust (

Agag & Eid, 2019).

5.2. H7: Platform Trust and Borrowing Intention

The study revealed a significant positive relationship between platform trust and borrowing intention in both Indonesia and Malaysia, indicating that users who trust the PayLater platform are more likely to express an intention to borrow money through the platform. This result aligns with previous studies (

Hooda et al., 2022) that have demonstrated the critical role of trust in enhancing users’ intentions to adopt digital financial services. Trust is a vital component in reducing the perceived risks associated with online financial transactions, as it increases users’ confidence in the platform’s ability to deliver secure, reliable, and transparent services. When users trust the platform, they are more inclined to engage with it, which in turn, increases their likelihood of borrowing.

This relationship is significant across both Indonesian and Malaysian respondents, reinforcing the notion that trust is a universal determinant of borrowing intention. While local contextual factors might influence the specific reasons for trust, the fundamental role of trust in driving borrowing intention remains consistent. This suggests that PayLater platforms, regardless of market, should prioritize building and maintaining trust, as it directly impacts users’ likelihood to engage with the service.

5.3. H8: Borrowing Intention and Actual Use

The study also found a strong positive relationship between borrowing intention and actual use of the PayLater service in both Indonesia and Malaysia. This indicates that users who express a strong intention to borrow through the platform are more likely to follow through and actually use the service. This finding is consistent with the theory of planned behavior (

Ajzen, 2012), which posits that intentions are strong predictors of actual behavior. The relationship between intention and behavior is particularly relevant in the context of BNPL services, where users’ initial intentions are often shaped by the perceived benefits and flexibility offered by the service, such as the ability to make purchases now and pay later.

The strong influence of borrowing intention on actual use underscores the importance of fostering positive borrowing intentions. By shaping users’ intentions to borrow, PayLater platforms can significantly increase the likelihood of actual usage. This finding highlights the critical role of psychological factors, such as the user’s confidence in their ability to repay and their perception of the benefits offered by the platform, in influencing platform adoption and usage.

5.4. Platform Trust as Mediation

Trust in online lending platforms has a significant mediating effect on borrowing intentions and then affects actual usage in both Malaysia and Indonesia. However, the factors shaping platform trust are different. In Malaysia, the factors that shape trust in online lending platforms are information quality, reputation, and perceived risk. Meanwhile, in Indonesia, reputation and structured assurance. The results of statistical testing for indirect effects are shown in

Table 4 for the Malaysian sample and

Table 5 for the Indonesian sample. The PLS analysis results show that platform trust is a key factor influencing borrowing intention and actual use. This finding is in line with previous research that emphasizes the importance of trust in driving new technology adoption (

Samarasekara et al., 2023).

5.5. Platform Trust as Mediation Between Information Quality and Borrowing Intention

In Malaysia, information quality significantly affects users’ interest in using PayLater, mainly through the mediation of trust. Research shows that high-quality information increases customer trust, which in turn, affects the intention to use electronic payment systems. This relationship is particularly important, where trust acts as a mediator between information quality and user engagement. Trust mediates the relationship between information quality and users’ intention to engage with PayLater, as shown in various studies (

Pratondo et al., 2023).

5.6. Platform Trust as Mediation Between Structured Assurance and Borrowing Intention

In Indonesia, structured assurance plays an important role in building user trust in fintech services, with trust platforms acting as mediators that strengthen this relationship. Improving both aspects can encourage more users to adopt fintech, such as PayLater. Structured assurance significantly influences interest in using fintech, with trust acting as an important mediating factor. Structured assurance in the form of perceived security is critical in defending against cyber risks and protecting personal information, which significantly impacts individuals’ propensity to use fintech. In particular, perceived safety and perceived risk are important factors influencing intentions. Structured assurance, which includes the credibility of the fintech company and the user-friendly nature of the technology, increases perceived trust, thereby positively impacting users’ interest in utilizing fintech services. This mediating effect underscores the importance of trust in the adoption of advanced financial technologies (

Chawla et al., 2023).

5.7. Platform Trust as Mediation Between Reputation and Borrowing Intention

In both Malaysia and Indonesia, strong reputation and positive user feedback, payment security can significantly increase trust, leading to increased interest in using services such as PayLater (

Wu et al., 2022). The relationship between reputation and interest in using fintech payers is significantly influenced by trust, which acts as a mediating factor. Research shows that, while perceived benefits increase interest in digital payments, perceived risks can deter users. Trust emerges as an important element that not only fosters interest but also mitigates the negative impact of perceived risks on user engagement with fintech services. A strong reputation can increase trust, which in turn, increases the likelihood of users engaging with fintech services. Trust propensity and perceived reputation are significant facilitators of consumer confidence, and conversely, lack of trust can lead to hesitation in adopting fintech solutions, highlighting the importance of building a reputable image in the fintech sector (

Zhao et al., 2024).

5.8. Platform Trust as Mediation Between Perceived Risk and Borrowing Intention

In Malaysia, the presence of a trust platform significantly mediates the risk associated with using PayLater services, influencing consumer interest. Trust acts as a buffer against perceived risk, increasing user satisfaction and driving engagement with the PayLater option. Trust mediates the relationship between perceived risk and continuing intention to adopt fintech. Higher trust can reduce perceived risk, thereby positively influencing an individual’s intention to continue using this lending option (

Purnama et al., 2023). A strong trust platform can increase user engagement, which leads to an increased willingness to use PayLater services, despite the risks faced. Trust platforms significantly influence risk mitigation in the context of PayLater usage by increasing user confidence and reducing perceived risks associated with online transactions. Trust mechanisms, such as secure payment processes and platform reputation, play an important role in shaping users’ willingness to engage with these systems.

5.9. Borrowing Intention as Mediation Between Platform Trust and Actual Use

In both Indonesia and Malaysia, the role of borrowing intentions as a factor mediating the relationship between platform trust and actual usage is significant, as evidenced by various studies. Trust affects users’ intention to engage with the platform, which in turn, affects their actual usage. This mediation is critical to understanding user behavior in digital environments. As in

Kim and Yum (

2024), fintech platforms can improve user experience by focusing on service quality and building trust, which then increases usage intention.

6. Implications and Recommendations

The findings of this study have significant implications for the development and marketing of PayLater services, highlighting the critical role of platform trust in shaping borrowing intentions and actual usage. Reputation emerges as a key driver of platform trust in both Indonesia and Malaysia, reinforcing trust theory (

Mayer et al., 1995), which posits that reputation is fundamental in building trust in digital-based services. From a practical standpoint, PayLater service providers should prioritize reputation management by leveraging positive testimonials, user ratings, and industry achievements to enhance consumer confidence. Displaying these trust signals prominently can serve as an effective marketing strategy to attract potential users.

However, the factors influencing platform trust differ between Indonesian and Malaysian consumers due to distinct regulatory and market conditions. In Indonesia, the online lending sector faces persistent challenges related to regulatory oversight and fraudulent lending practices, making structured assurances a primary concern for potential users. To address these concerns, PayLater platforms should focus on reinforcing security measures and consumer protection policies. Providing transparent information on data security, privacy policies, and user protection mechanisms can significantly enhance trust among Indonesian consumers. In contrast, Malaysia has a more mature and regulated fintech ecosystem, with strong oversight from Bank Negara Malaysia (BNM). Given the clearer regulatory environment, Malaysian users place greater emphasis on the quality of information available on the platform when making borrowing decisions. To cater to this preference, PayLater services in Malaysia should prioritize transparent communication regarding lending terms, interest rates, and potential risks. By clearly outlining safeguards and risk mitigation measures, platforms can alleviate user concerns and further strengthen trust.

The study also highlights that platform trust is a powerful predictor of borrowing intention and actual use. These results reinforce the theory that explains how trust is a key factor in technology-based service adoption decisions. In the technology acceptance model (TAM), trust can act as a factor that influences intention and actual use. Trust increases certain aspects of the perceived usefulness of a service (

Gefen et al., 2003). The usefulness of a fintech service depends on the service being honest, caring, and capable, as customers expect. Therefore, PayLater services should focus on strategies that not only enhance users’ trust but also encourage positive borrowing intentions. This can be achieved by offering competitive benefits, such as flexible repayment terms, and ensuring that the borrowing process is easy, transparent, and user-friendly. Additionally, platforms should work towards reducing perceived risks by implementing robust security features and providing clear, accessible customer support to address any concerns users may have.

Finally, since borrowing intention strongly influences actual use, it is crucial for PayLater platforms to design services that make it easy for users to transition from intending to borrow to actually using the service. This can include simplifying the sign-up process, streamlining credit approval procedures, and providing easy-to-understand payment structures that cater to the diverse needs of users.

7. Conclusions

This study offers a deeper understanding of the dynamics between platform trust, borrowing intention, and actual use in the context of PayLater services in Indonesia and Malaysia. The differences between the two countries underscore the importance of tailoring trust-building strategies to local consumer behavior and perceptions. As platform trust plays a central role in determining borrowing intention and actual use, service providers should prioritize reputation, security assurances, and transparency to foster trust. Moreover, understanding the cultural and market-specific differences in consumer behavior will be essential for fintech platforms to successfully penetrate and grow in diverse markets.

A key limitation of this study lies in its exclusive focus on existing PayLater users, which may introduce sampling bias and limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of fintech users. Since PayLater services were only recently introduced—around 2019 in Indonesia and 2020 in Malaysia—and were initially met with skepticism due to regulatory concerns and negative publicity, current users may represent early adopters with more favorable attitudes. This could skew the results and under-represent the perspectives of non-users or more cautious potential adopters. To address this, future research should incorporate more diverse and representative samples, including both users and non-users, and across varied demographic and regional profiles, to enhance external validity. Moreover, given that some of the variables in this study were found to be statistically insignificant, future studies could explore additional constructs such as perceived ease of use, financial literacy, digital trust, risk tolerance, and the influence of social networks. Qualitative or mixed-methods approaches might also be valuable in uncovering deeper behavioral motivations and context-specific drivers of fintech adoption that quantitative models alone may not capture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.K.P. and C.J.; methodology, T.K.P.; software, T.K.P.; validation, G.O.W., C.J. and F.K.; formal analysis, T.K.P.; investigation, T.K.P.; resources, T.K.P.; data curation, G.O.W. and N.H.; writing—original draft preparation, F.K.; writing—review and editing, N.H.; visualization, G.O.W.; supervision, T.K.P.; project administration, F.K.; funding acquisition, T.K.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is funded by the Research and Community Service Universitas Pembangunan Nasional Veteran Jawa Timur, Indonesia, funding number SPP/204/UN.63.8/LT/VI/2024.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical review and approval were waived for this study due to the research does not involve any sensitive or high-risk questions, and the respondents in this research are anonymous.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects through their voluntary participation in completing the questionnaire.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| BNPL | Buy Now, Pay Later |

| BNM | Bank Negara Malaysia |

| OJK | Otoritas Jasa Keuangan |

| TAM | Technology Acceptance Model |

| PLS | Partial Least Squares |

| SACM | Structured Assurance Case Metamode |

| OMG | Object Management Group |

Appendix A

Table A1.

Question item list.

Table A1.

Question item list.

| Construct | Measurement Items | Source |

|---|

| Service quality | I am satisfied with the overall service quality provided by the PayLater service. | (Rana et al., 2025) |

| The customer support of the PayLater service is responsive to my issues. |

| To what extent do you agree that the PayLater service is reliable and performs consistently? |

| Information quality | Information provided about PayLater services is clear and understandable. | (Wu et al., 2022) |

| Information about PayLater service fees and rates is transparent. |

| Information about my PayLater account and transactions is accurate. |

| I am satisfied with the updates and notifications provided by the PayLater service. |

| The information available on the PayLater service website or app is useful for my financial decisions. |

| Structural assurance | I am confident in the security measures implemented by the PayLater service to protect my personal and financial information. | (Gefen et al., 2003; Mousavizadeh et al., 2016) |

| PayLater service has a clear and fair policy for resolving disputes. |

| I find the PayLater service trustworthy in handling my financial transactions. |

| I am satisfied with the assurance provided by the PayLater service regarding data privacy. |

| The PayLater service communicates its terms and conditions clearly to me. |

| Awareness | I already know about PayLater Service. | (L. George et al., 2022) |

| I know the risks of using PayLater Service. |

| I am aware that PayLater Services are supervised and regulated by the Financial Services Authority. |

| I know the role of family and environment in increasing financial awareness. |

| Reputation (My PayLater service) | Has a reputation for honesty. | (Yap et al., 2010) |

| Is known for caring about its customers. |

| Will do its job properly even if it is unsupervised. |

| Has a bad reputation in the market (reverse code). |

| Is known to be reliable. |

| Perceived risk | How would you describe the decision to transact with this PayLater service? (Significant risk/insignificant risk.) | (Pavlou, 2003) |

| How would you describe the decision to transact with this PayLater service? (Very negative situation/very positive situation.) |

| How would you describe the decision to make a product purchase using this PayLater Service? (High potential loss/high potential gain.) |

| Platform trust | The PayLater service I use is trustworthy. | (Suh & Han, 2002) |

| I believe in the benefits of my decision to use PayLater services. |

| The PayLater service that I use keeps its promises and commitments. |

| The PayLater service I use always considers the best interests of its users. |

| The PayLater service that I use will function properly even if it is not always monitored. I trust the PayLater service that I use. |

| The PayLater service I use is trustworthy. |

| Borrowing intention | I intend to use the PayLater service for my future purchases. |

| I plan to rely on the PayLater service to manage my short-term financial needs. | (Suh & Han, 2002) |

| I would likely recommend PayLater service to my friends and family. |

| I find the PayLater service a convenient way to handle unexpected expenses. |

| Actual use | I regularly use the PayLater service for my purchases. | (Suh & Han, 2002) |

| I have used the PayLater service several times in the last three months. |

| I use the PayLater service to make large purchases that I cannot pay for outright. |

| The PayLater service is my primary method for managing my cash flow. |

| I frequently check and manage my PayLater account for my spending needs. |

Appendix B

Table A2.

Loading factor Indonesian and Malaysian sample.

Table A2.

Loading factor Indonesian and Malaysian sample.

| Indonesian Sample | Malaysian Sample |

|---|

| Indicator of variables | Loading Factor | Indicator of variables | Loading Factor |

| Service Quality | | Service Quality | |

| X1.1 | 0.809 | X1.1 | 0.85 |

| X1.2 | 0.789 | X1.2 | 0.818 |

| X1.4 | 0.789 | X1.3 | 0.891 |

| X1.5 | 0.714 | X1.4 | 0.861 |

| | | X1.5 | 0.876 |

| Information quality | | Information quality | |

| X2.2 | 0.721 | X2.1 | 0.866 |

| X2.3 | 0.795 | X2.2 | 0.81 |

| X2.4 | 0.896 | X2.3 | 0.86 |

| X2.5 | 0.820 | X2.4 | 0.827 |

| | | X2.5 | 0.866 |

| Structured assurance | | Structured assurance | |

| X3.1 | 0.832 | X3.1 | 0.892 |

| X3.2 | 0.802 | X3.2 | 0.824 |

| X3.3 | 0.854 | X3.3 | 0.857 |

| X3.4 | 0.743 | X3.4 | 0.909 |

| X3.5 | 0.875 | X3.5 | 0.874 |

| Awareness | | Awareness | |

| X4.1 | 0.787 | X4.1 | 0.819 |

| X4.2 | 0.849 | X4.2 | 0.73 |

| X4.3 | 0.896 | X4.3 | 0.757 |

| X4.4 | 0.708 | X4.4 | 0.723 |

| Reputation | | Reputation | |

| X5.1 | 0.853 | X5.1 | 0.847 |

| X5.2 | 0.765 | X5.2 | 0.866 |

| X5.3 | 0.894 | X5.3 | 0.851 |

| X5.5 | 0.823 | X5.5 | 0.816 |

| Perceived risk | | Perceived risk | |

| X6.2 | 0.933 | X6.1 | 0.842 |

| X6.3 | 0.925 | X6.2 | 0.859 |

| | | X6.3 | 0.855 |

| Platform trust | | Platform trust | |

| X7.1 | 0.795 | X7.1 | 0.902 |

| X7.2 | 0.847 | X7.2 | 0.828 |

| X7.3 | 0.872 | X7.3 | 0.888 |

| X7.4 | 0.806 | X7.4 | 0.848 |

| X7.5 | 0.826 | X7.5 | 0.716 |

| X7.6 | 0.860 | X7.6 | 0.826 |

| Borrowing intention | | Borrowing intention | |

| X8.1 | 0.833 | X8.1 | 0.912 |

| X8.2 | 0.834 | X8.2 | 0.815 |

| X8.3 | 0.888 | X8.3 | 0.794 |

| X8.4 | 0.822 | X8.4 | 0.772 |

| X8.5 | 0.788 | X8.5 | 0.783 |

| Actual use | | Actual use | |

| X9.1 | 0.875 | X9.1 | 0.824 |

| X9.2 | 0.856 | X9.2 | 0.836 |

| X9.4 | 0.893 | X9.3 | 0.849 |

| X9.5 | 0.891 | X9.4 | 0.796 |

| | | X9.5 | 0.792 |

References

- Agag, G., & Eid, R. (2019). Examining the antecedents and consequences of trust in the context of peer-to-peer accommodation. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 81, 180–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I. (2012). The theory of planned behavior. In Handbook of theories of social psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 438–459). Sage. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzaidi, M. S., & Agag, G. (2022). The role of trust and privacy concerns in using social media for e-retail services: The moderating role of COVID-19. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 68, 103042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvidsson, N. (2019). Building a cashless society: The Swedish route to the future of cash payments. Issue November. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Azzahra, K., Rahayu Zees, S., & Ayundyayasti, P. (2023). Factors influence the intention to use in paylater feature among the Millennial Generation. Applied Accounting and Management Review (AAMAR), 2(2). Available online: https://jurnal.polines.ac.id/index.php/AAMAR (accessed on 20 January 2025). [CrossRef]

- Brune, L., Chyn, E., & Kerwin, J. (2021). Pay me later: Savings constraints and the demand for deferred payments. American Economic Review, 111(7), 2179–2212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cardoso, A., & Cardoso, M. (2024). Bank reputation and trust: Impact on client satisfaction and loyalty for Portuguese clients. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(7), 277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castaldo, S., Premazzi, K., & Zerbini, F. (2010). The meaning(s) of trust. A content analysis on the diverse conceptualizations of trust in scholarly research on business relationships. Journal of Business Ethics, 96(4), 657–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, P., Das, D., & Rawat, D. B. (2024). Digital twin for credit card fraud detection: Opportunities, challenges, and fraud detection advancements. Future Generation Computer Systems, 158, 410–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chawla, U., Mohnot, R., Singh, H. V., & Banerjee, A. (2023). The mediating effect of perceived trust in the adoption of cutting-edge financial technology among digital natives in the post-COVID-19 era. Economies, 11(12), 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D., Lou, H., & Van Slyke, C. (2015). Toward an understanding of online lending intentions: Evidence from a survey in China. Communications of the Association for Information Systems, 36, 317–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X., Huang, X., Yang, B., Chen, S., & Yan, Y. (2024). How perceived justice leads to stickiness to short-term rental platforms: Unveiling the effect of relationship commitment and trust. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 66, 101422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Culot, G., Nassimbeni, G., Podrecca, M., & Sartor, M. (2021). The ISO/IEC 27001 information security management standard: Literature review and theory-based research agenda. TQM Journal, 33(7), 76–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daneshgadeh, S., & Yıldırım, S. Ö. (2014). Empirical investigation of internet banking usage: The case of Turkey. Procedia Technology, 16, 322–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eastlick, M. A., Lotz, S. L., & Warrington, P. (2006). Understanding online B-to-C relationships: An integrated model of privacy concerns, trust, and commitment. Journal of Business Research, 59(8), 877–886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitriyah, N. W., & Nadlifatin, R. (2024). Behavioral factors of intention to use pay later services. A systematic literature review. E3S Web of Conferences, 501, 02010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garrouch, K. (2021). Does the reputation of the provider matter? A model explaining the continuance intention of mobile wallet applications. Journal of Decision Systems, 30(2–3), 150–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gefen, D., Karahanna, E., & Straub, D. W. (2003). Trust and TAM in online shopping: An integrated model. MIS Quarterly, 27(1), 51–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A., & Gireeshkumar, G. S. (2013). User awareness of security features in internet banking-an empirical investigation. Adarsh Journal of Management Research, 6(1), 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, L., Ahmed Abdul Nabi Al-Balushi, S., Abdul Wahab Al-Balushi, M., & Mohammed Khamis Al-Zadjali, H. (2022). Investors’ awareness and perception of P2P lending platform with special reference to investors in muscat governorate. International Journal of Innovative Science and Research Technology, 7(3), 896–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., Black, W. C., & Anderson, R. E. (2019). Multivariate data analysis (8th ed.). Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Hooda, A., Gupta, P., Jeyaraj, A., Giannakis, M., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). The effects of trust on behavioral intention and use behavior within e-government contexts. International Journal of Information Management, 67, 102553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadil, Y., Rana, N. P., & Dwivedi, Y. K. (2022). Understanding the drivers of online trust and intention to buy on a website: An emerging market perspective. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(1), 100065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jafri, J. A., Mohd Amin, S. I., Abdul Rahman, A., & Mohd Nor, S. (2024). A systematic literature review of the role of trust and security on Fintech adoption in banking. Heliyon, 10(1), e22980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaabachi, S., Ben Mrad, S., & Petrescu, M. (2017). Consumer initial trust toward internet-only banks in France. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 35(6), 903–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khairunnisa, S. A., Rahman, M. C., Apriyanti, C., Putri, D. O., & Fajrussalam, H. (2022). Perilaku Konsumtif Penggunaan online shopping dan Sistem Pay Later dalam Perspektif Ekonomi Islam. Jurnal Pendidikan Dasar, 6(1), 130–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J., & Yum, K. (2024). Enhancing continuous usage intention in e-commerce marketplace platforms: The effects of service quality, customer satisfaction, and trust. Applied Sciences, 14(17), 7617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mail Malay. (2025). Economist urges BNM, employers to tighten BNPL rules amid rising youth debt. Available online: https://www.malaymail.com/news/malaysia/2025/02/18/economist-urges-bnm-employers-to-tighten-bnpl-rules-amid-rising-youth-debt/167039 (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Manghani, K. (2011). Quality assurance: Importance of systems and standard operating procedures. Perspectives in Clinical Research, 2(1), 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D. (1995). An integrative model of organizational trust. Academy of Management Review, 20(3), 709–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKnight, D. H., Choudhury, V., & Kacmar, C. (2002). Developing and validating trust measures for e-commerce: An integrative typology. Information Systems Research, 13(3), 334–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V. (1992). Understanding consumers’ behaviour: Can perceived risk theory help? Management Decision, 30(3). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, V. (1999). Consumer perceived risk: Conceptualisations and models. European Journal of Marketing, 33(1–2), 163–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousavizadeh, M., Kim, D. J., & Chen, R. (2016). Effects of assurance mechanisms and consumer concerns on online purchase decisions: An empirical study. Decision Support Systems, 92, 79–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, Y. T. H., Tapanainen, T., & Nguyen, H. T. T. (2022). Reputation and its consequences in Fintech services: The case of mobile banking. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 40(7), 1364–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nur, T., & Azzahra, H. (2023, October 6–7). The influence of behavioral intention of using PayLater apps on consumptive behavior moderated by financial literacy. 5th International Conference on Cybernetics and Intelligent Systems, ICORIS 2023, Pangkalpinang, Indonesia. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osman, I., Ariffin, N. A. M., Yuraimie, M. F. N. B. M., Ali, M. F. B., & Akbar, M. A. F. B. N. (2024). How buy now, pay later (BNPL) is shaping gen Z’s spending spree in Malaysia. Information Management and Business Review, 16(3), 657–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, G., Mao, Y., Song, Z., & Nie, H. (2024). Research on the influencing factors of adult learners’ intent to use online education platforms based on expectation confirmation theory. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 12762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pavlou, P. A. (2003). Consumer acceptance of electronic commerce: Integrating trust and risk with the technology acceptance model. International Journal of Electronic Commerce, 7(3), 101–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pratondo, K. R., Marsudi, M., & Wijaya, R. (2023). Customer trust and interaction quality as a mediating: The effect of quality of information on purchase decision. Business Innovation Management and Entrepreneurship Journal (BIMANTARA), 2(02), 106–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purnama, E. S., Suryadi, N., & Andarwati, A. (2023). The influence of perceived risk and perceived benefits on continuance intention to adopt Fintech P2P lending mediated by trust in Indonesia. Journal of Business and Management Review, 4(10), 754–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qalati, S. A., Vela, E. G., Li, W., Dakhan, S. A., Hong Thuy, T. T., & Merani, S. H. (2021). Effects of perceived service quality, website quality, and reputation on purchase intention: The mediating and moderating roles of trust and perceived risk in online shopping. Cogent Business and Management, 8(1), 1869363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramli, R. R., & Setiawan, S. R. D. (2024). Pinjaman paylater tumbuh pesat, ada kaitannya dengan daya beli masyarakat? Halaman all—Kompas.com. Available online: https://money.kompas.com/read/2024/10/03/160333626/pinjaman-paylater-tumbuh-pesat-ada-kaitannya-dengan-daya-beli-masyarakat?page=all#google_vignette (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Rana, Md. M., Siddiqee, M. S., & Uddin, Md. A. (2025). The service quality imperative: Sustaining ridesharing adoption in the developing world. Research in Transportation Business & Management, 59, 101289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research and Markets. (2025). Malaysia Buy now pay later business and investment opportunities databook—75+ KPIs on BNPL market size, end-use sectors, market share, product analysis, business model, demographics—Q1 2025 update. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/5305023/malaysia-buy-now-pay-later-business-and?utm_source=GNE&utm_medium=PressRelease&utm_code=jh37gs&utm_campaign=2043907+-+Malaysia+Buy+Now+Pay+Later+Business+Report+2025%3A+BNPL+Payments+to+Grow+by+15.1%25+to (accessed on 20 February 2025).

- Revolusi, P. (2024). Pernyataan dirjen IKP kominfo terkait dugaan kebocoran data pribadi DJP. Direktur Jenderal Informasi Dan Komunikasi Publik Kominfo. Available online: https://www.komdigi.go.id/berita/siaran-pers/detail/pernyataan-dirjen-ikp-kominfo-terkait-dugaan-kebocoran-data-pribadi-djp (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations (5th ed.). Free Press. Available online: https://books.google.co.id/books?id=9U1K5LjUOwEC (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Saeed, S. (2023). A customer-centric view of e-commerce security and privacy. Applied Sciences, 13(2), 1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samarasekara, L., Tanaraj, K., Rajespari, K., Sundarasen, S., & Rajagopalan, U. (2023). Unlocking the key drivers of FinTech adoption: The mediating role of trust among Malaysians. Migration Letters, 20(3), 505–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, K., Asri, H. R., Gisijanto, H. A., Kencana, A. P. P., & Ramadhan, I. C. (2023). Analysis of the effect of service quality on customer loyalty and satisfaction using expectation confirmation model and servqual. JEMSI (Jurnal Ekonomi, Manajemen, Dan Akuntansi), 9(3), 812–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shamsuzzoha, A., Blomqvist, H., & Takala, J. (2023). Service productisation through standardisation and modularisation: An exploratory case study. International Journal of Sustainable Engineering, 17(1), 1154–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, M. (1973). Job market signaling. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 87(3), 355–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suh, B., & Han, I. (2002). Effect of trust on customer acceptance of Internet banking. Electronic Commerce Research and Applications, 1(3–4), 247–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szabó, K. (2024). Platforms and trust as two columns of sharing economy. Észak-Magyarországi Stratégiai Füzetek, 21(2), 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Cruijsen, C., de Haan, J., & Roerink, R. (2023). Trust in financial institutions: A survey. Journal of Economic Surveys, 37(4), 1214–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S., & Huang, Z. (2025). Trust transfer in the adoption of autonomous last mile services toward digital urban system. Digital Engineering, 5, 100030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R., Kelly, T. P., Dai, X., Zhao, S., & Hawkins, R. (2019). Model based system assurance using the structured assurance case metamodel. Journal of Systems and Software, 154, 211–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y., Ban, N., Chen, X., Wang, D., & Li, S. (2022). Trust research on Didi platform: About influencing factors and willingness to use. International Journal of Business Management and Finance Research, 5(1), 17–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J., Benbasat, I., & Cenfetelli, R. T. (2013). Integrating service quality with system and information quality: An empirical test in the e-service context. MIS Quarterly, 37(3), 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Q., & Lee, Y.-C. (2016). Influencing factors on the lending intention of online peer-to-peer lending: Lessons from Renrendai.com. The Journal of Information Systems, 25(2), 79–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y., Wang, Y., Liu, J., & Lee, K. (2024). An empirical study on the structural assurance mechanism for trust building in autonomous vehicles based on the trust-in-automation three-factor model. Sustainability, 16(18), 8258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yap, K. B., Wong, D. H., Loh, C., & Bak, R. (2010). Offline and online banking—Where to draw the line when building trust in e-banking? International Journal of Bank Marketing, 28(1), 27–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H., Khaliq, N., Li, C., Rehman, F. U., & Popp, J. (2024). Exploring trust determinants influencing the intention to use fintech via SEM approach: Evidence from Pakistan. Heliyon, 10(8), e29716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).