Unlock Your Firm Value with ESG Performance? Evidence from ASX-Listed Companies

Abstract

1. Introduction

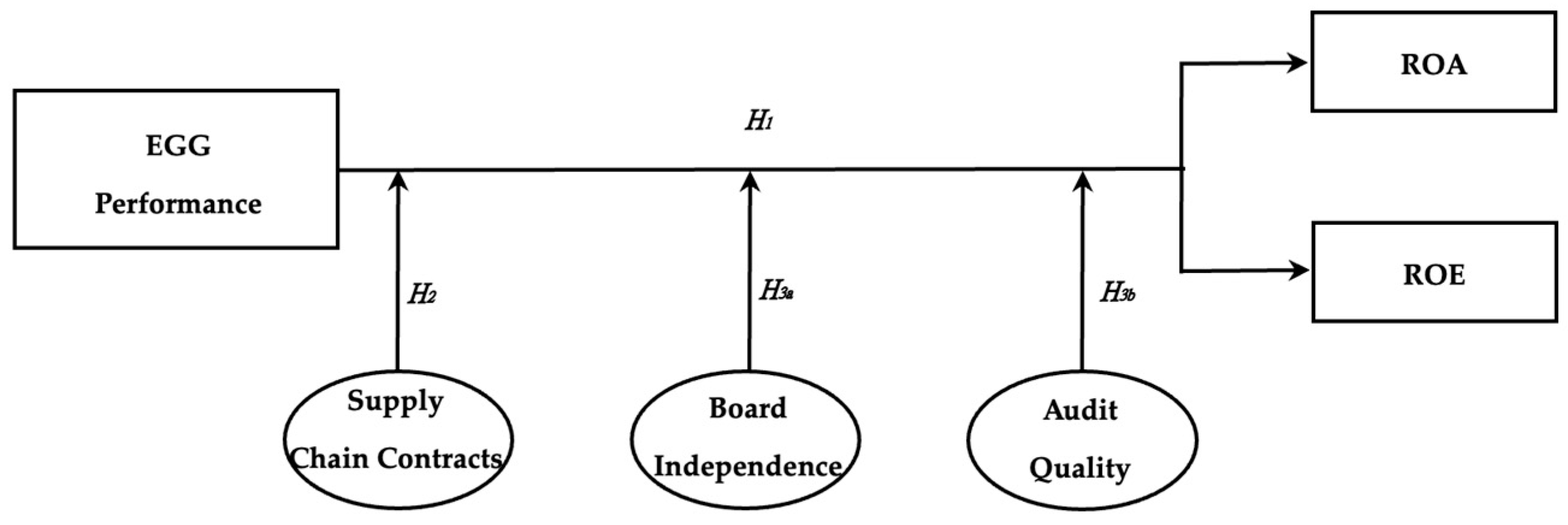

2. Literature Review, Conceptual Framework, and Hypotheses

2.1. Conceptual Framework

2.2. ESG Performance and Firm Value

2.3. The Moderating Effect of Supply Chain Contracts

2.4. The Moderating Effect of Corporate Governance (Board Independence and Audit Quality)

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample and Data Description

3.2. Variable Definition and Measurements

3.2.1. Independent Variables

ESG Performance

3.2.2. Dependent Variables

Firm Value

3.2.3. Moderating Variables

Supply Chain Contracting

Board Independence

Audit Quality

3.2.4. Control Variables

3.2.5. Empirical Models

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

4.2. Empirical Results

4.2.1. ESG and Firm Value (H1)

4.2.2. Moderating Effect of Supply Chain Partners (H2)

4.2.3. Moderating Effect of Board Independence (H3a)

4.2.4. Moderating Effect of Audit Quality (H3b)

4.3. Robustness and Endogenity Tests

4.3.1. Alternative Measure of Supply Chain Contacts

4.3.2. Excluding the COVID-19 Period

4.3.3. Weighted Least Squares

4.3.4. Propensity Score-Matching Method

5. Conclusions, Limitations, and Future Research

5.1. Theoretical Contributions

5.2. Practical Contributions

5.3. Limitations and Future Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviation

| ESG | Environment, social, and governance |

References

- Abid, A., Shaique, M., & Anwar ul Haq, M. (2018). Do big four auditors always provide higher audit quality? Evidence from Pakistan. International Journal of Financial Studies, 6(2), 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, R., El Chaarani, H., & Tao, Z. (2024). The impact of audit oversight quality on the financial performance of U.S. firms: A subjective assessment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(4), 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agyabeng-Mensah, Y., Ahenkorah, E., Afum, E., Nana Agyemang, A., Agnikpe, C., & Rogers, F. (2020). Examining the influence of internal green supply chain practices, green human resource management and supply chain environmental cooperation on firm performance. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 25(5), 585–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, W., Khan, M. A., Najmi, A., & Khan, S. A. (2023). Strategizing risk information sharing framework among supply chain partners for financial performance. Supply Chain Forum: An International Journal, 24(2), 233–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Gamrh, B., & Al-dhamari, R. (2014). Firm characteristics and corporate social responsibility disclosure in Saudi Arabia [Working Paper (International Business Management)]. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2907396 (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Aouadi, A., & Marsat, S. (2018). Do ESG controversies matter for firm value? Evidence from international data. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(4), 1027–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armour, C., Hunt, D., & Lwin, J. (2023, September Quarter). Green and sustainable finance in Australia. Reserve Bank of Australia Bulletin. Available online: https://rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2023/sep/pdf/bulletin-2023-09.pdf (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- ASIC. (2022). Improving and maintaining audit quality. Available online: https://asic.gov.au/regulatory-resources/financial-reporting-and-audit/auditors/improving-and-maintaining-audit-quality/#why (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Bacha, S., Ajina, A., & Ben Saad, S. (2021). CSR performance and the cost of debt: Does audit quality matter? Corporate Governance, 21(1), 137–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baid, V., & Jayaraman, V. (2022). Amplifying and promoting the “S” in ESG investing: The case for social responsibility in supply chain financing. Managerial Finance, 48(8), 1279–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barnea, A., & Rubin, A. (2010). Corporate social responsibility as a conflict between shareholders. Journal of Business Ethics, 97(1), 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barney, J. (1991). Special theory forum the resource-based model of the firm: Origins, implications, and prospects. Journal of Management, 17(1), 97–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, M. E., Cram, D. P., & Nelson, K. K. (2001). Accruals and the prediction of future cash flows. The Accounting Review, 76(1), 27–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bashir, Y., Zhao, Y., Qiu, H., Ahmed, Z., & Yau, J. T.-H. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance performance and value creation in product market: Evidence from emerging economies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 16(12), 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behl, A., Kumari, P. S. R., Makhija, H., & Sharma, D. (2022). Exploring the relationship of ESG score and firm value using cross-lagged panel analyses: Case of the Indian energy sector. Annals of Operations Research, 313(1), 231–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhimavarapu, V. M., Rastogi, S., Gupte, R., Pinto, G., & Shingade, S. (2022). Does the impact of transparency and disclosure on the firm’s valuation depend on the ESG? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 15(9), 410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchanan, J. L., Commerford, B. P., & Wang, E. (2021). Auditor actions and the deterrence of manager opportunism: The importance of communication to the board and consistency with peer behavior. The Accounting Review, 96(3), 141–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukari, A., Agyemang, A. O., & Bawuah, B. (2024). Assessing the moderating role of ESG performance on corporate governance and firm value in developing countries. Cogent Business & Management, 11(1). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, W., Ellinger, A. E., Kim, K., & Franke, G. R. (2016). Supply chain integration and firm financial performance: A meta-analysis of positional advantage mediation and moderating factors. European Management Journal, 34(3), 282–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charles, A., Lauras, M., Van Wassenhove, L., Tatham, P., & Pettit, S. (2010). A model to define and assess the agility of supply chains: Building on humanitarian experience. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 40(8/9), 722–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatain, O. (2011). Value creation, competition, and performance in buyer-supplier relationships. Strategic Management Journal, 32(1), 76–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C. X., Lu, H., & Sougiannis, T. (2012). The Agency problem, corporate governance, and the asymmetrical behavior of selling, general, and administrative costs. Contemporary Accounting Research, 29(1), 252–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Krishnan, G. V., Li, W., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Do big 4 auditors enhance audit quality in China? A “behind the scenes look”. Journal of International Accounting Research, 21(2), 31–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S., Song, Y., & Gao, P. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and financial outcomes: Analyzing the impact of ESG on financial performance. Journal of Environmental Management, 345, 118829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, R., Kim, H., & Ryu, D. (2024). ESG performance and firm value in the Chinese market. The Investment Analysts Journal, 53(1), 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouaibi, S., & Affes, H. (2021). The effect of social and ethical practices on environmental disclosure: Evidence from an international ESG data. Corporate Governance, 21(7), 1293–1317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christopher, M., Mena, C., Khan, O., & Yurt, O. (2011). Approaches to managing global sourcing risk. Supply Chain Management, 16(2), 67–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clément, A., Robinot, É., & Trespeuch, L. (2023). The use of ESG scores in academic literature: A systematic literature review. Journal of Enterprising Communities, 19(1), 92–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantiello, A., & Leogrande, A. (2023). The impact of research and development expenditures on ESG model in the global economy. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4414232 (accessed on 24 April 2025). [CrossRef]

- Dakhli, A. (2022). The impact of corporate social responsibility on firm financial performance: Does audit quality matter? Journal of Applied Accounting Research, 23(5), 950–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dam, L., & Scholtens, B. (2015). Toward a theory of responsible investing: On the economic foundations of corporate social responsibility. Resource and Energy Economics, 41, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Villiers, C., Naiker, V., & van Staden, C. J. (2011). The effect of board characteristics on firm environmental performance. Journal of Management, 37(6), 1636–1663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diego, J., & Montes-Sancho, M. J. (2024). Nexus supplier transparency and supply network accessibility: Effects on buyer ESG risk exposure. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 45(4), 895–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diez-Cañamero, B., Bishara, T., Otegi-Olaso, J. R., Minguez, R., & Fernández, J. M. (2020). Measurement of corporate social responsibility: A review of corporate sustainability indexes, rankings and ratings. Sustainability, 12(5), 2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dincă, M. S., Vezeteu, C.-D., & Dincă, D. (2022). The relationship between ESG and firm value. Case study of the automotive industry. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 10, 1059906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Y., Liang, C., & Wanyin, Z. (2023). Board diversity and firm performance: Impact of ESG activities in China. Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 1592–1609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drempetic, S., Klein, C., & Zwergel, B. (2020). The influence of firm size on the ESG score: Corporate sustainability ratings under review. Journal of Business Ethics, 167(2), 333–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y., Yang, F., & Xiong, L. (2023). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) performance and firm value: Evidence from Chinese manufacturing firms. Sustainability, 15(17), 12858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duque-Grisales, E., & Aguilera-Caracuel, J. (2021). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores and financial performance of multilatinas: Moderating effects of geographic international diversification and financial slack. Journal of Business Ethics, 168(2), 315–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ernst & Young. (2021). Is your ESG data unblocking long-term value? E. Young. Available online: https://www.ey.com/en_gl/insights/assurance/is-your-esg-data-unlocking-long-term-value (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Fakhfakh, I., & Jarboui, A. (2021). The moderating role of audit quality on the relationship between auditor reporting and earnings management: Empirical evidence from Tunisia. EuroMed Journal of Business, 16(4), 416–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y., Jiang, Y., Kao, M.-F., & Liu, F. H. (2020). Board independence and firm value: A quasi-natural experiment using Taiwanese data. Journal of Empirical Finance, 57, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatemi, A., Glaum, M., & Kaiser, S. (2018). ESG performance and firm value: The moderating role of disclosure. Global Finance Journal, 38, 45–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, R. E., Harrison, J. S., Wicks, A. C., Purnell, L., & de Colle, S. (2010). Stakeholder theory: The state of the art. The Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 403–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friede, G., Busch, T., & Bassen, A. (2015). ESG and financial performance: Aggregated evidence from more than 2000 empirical studies. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 5(4), 210–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H., Jiang, Q., Cifuentes-Faura, J., & Chen, Q. (2024). Corporate environmental governance and firm value: Beyond greenwashing for sustainable development. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 26, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, M., Beck, J., Kopyto, M., & Spieske, A. (2022). Determining requirements and challenges for a sustainable and circular electric vehicle battery supply chain: A mixed-methods approach. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 33, 203–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gholami, A., Sands, J., & Shams, S. (2022). The impact of corporate ESG performance disclosure across australian industries [Article]. Australasian Accounting, Business and Finance Journal, 16(4), 180–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbins, M., Richardson, A., & Waterhouse, J. (1990). The management of corporate financial disclosures: Opportunism, ritualism, policies, and processes. Journal of Accounting Research, 28(1), 121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golicic, S. L., & Smith, C. D. (2013). A meta-analysis of environmentally sustainable supply chain management practices and firm performance. Journal of Supply Chain Management, 49(2), 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gull, A. A., Saeed, A., Suleman, M. T., & Mushtaq, R. (2022). Revisiting the association between environmental performance and financial performance: Does the level of environmental orientation matter? Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 29(5), 1647–1662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutterman, A. (2023). Board oversight of sustainability: A practical guide for directors and advisors. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S. (2017). The effect of debt choice on firm value. Journal of Applied Business Research, 33(1), 135–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, O.-K., Langli, J. C., & Thomas, W. B. (2012). Agency conflicts and auditing in private firms. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 37(7), 500–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, B.-X., Chen, Y.-M., & Chen, L.-A. (2022). Corporate social responsibility and value added in the supply chain: Model and mechanism. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 174, 121302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, D. Z. X. (2022). Environmental, social and governance factors and assessing firm value: Valuation, signalling and stakeholder perspectives. Accounting and Finance, 62(S1), 1983–2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huguet, D., & López Gandía, J. (2016). Audit and earnings management in Spanish SMEs. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 19(3), 171–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, H., & Samad, F. A. (2011). Agency costs, corporate governance mechanisms and performance of public listed family firms in Malaysia. South African Journal of Business Management, 42(3), 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, E. H., Yeh, C.-C., Wang, L.-H., & Fung, H.-G. (2018). The relationship between CSR and performance: Evidence in China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 51, 155–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kao, M.-F., Hodgkinson, L., & Jaafar, A. (2019). Ownership structure, board of directors and firm performance: Evidence from Taiwan. Corporate Governance (Bradford), 19(1), 189–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keter, C. K. S., Cheboi, J. Y., Kosgei, D., & Chepsergon, A. K. (2023). Financial performance and firm value of listed companies: Financial performance measure ROA versus ROE. Journal of Business, Economics and Management Research Studies, 1(3), 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Khoe, J. P., Sutejo, B. S., & Murhadi, W. R. (2024). Corporate governance of firm performance in the non-financial sector for the 2017–2021 period. In Proceedings of the 20th international symposium on management (INSYMA 2023) (pp. 93–98). Atlantis Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-B., Chung, R., & Firth, M. (2003). Auditor conservatism, asymmetric monitoring, and earnings management. Contemporary Accounting Research, 20(2), 323–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Y., Agyemang, A., Alessa, N., & Kongkuah, M. (2023). The moderating role of technological innovation on environment, social, and governance (ESG) performance and firm value: Evidence from developing and least-developed countries. Sustainability, 15(19), 14240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozlenkova, I. V., Samaha, S. A., & Palmatier, R. W. (2014). Resource-based theory in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krüger, P. (2015). Corporate goodness and shareholder wealth. Journal of Financial Economics, 115(2), 304–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P. (2024). Corporate disclosure and firm value: Do audit quality and foreign listing matter? Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, 21, 312–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Tran, V., & Coqueret, G. (2023). ESG news spillovers across the value chain. Financial Management, 52(4), 677–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, B., Petrovits, C., & Radhakrishnan, S. (2010). Is doing good good for you? how corporate charitable contributions enhance revenue growth. Strategic Management Journal, 31(2), 182–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima Crisóstomo, V., de Souza Freire, F., & Cortes de Vasconcellos, F. (2011). Corporate social responsibility, firm value and financial performance in Brazil. Social Responsibility Journal, 7(2), 295–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limkriangkrai, M., Koh, S., & Durand, R. B. (2017). Environmental, social, and governance (ESG) profiles, stock returns, and financial policy: Australian evidence. International Review of Finance, 17(3), 461–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F., Kim, B. C., & Park, K. (2022). Supplier-base concentration as a moderating variable in the non-linear relationship between R&D and firm value. Asian Journal of Technology Innovation, 30(2), 342–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livnat, J., Smith, G., Suslava, K., & Tarlie, M. (2021). Board tenure and firm performance. Global Finance Journal, 47, 100535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lokuwaduge, C., & de Silva, K. (2020). Emerging corporate disclosure of environmental social and governance (ESG) risks: An Australian study. Australasian Accounting, Business & Finance Journal, 14(2), 35–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longoni, A., & Cagliano, R. (2018). Inclusive environmental disclosure practices and firm performance: The role of green supply chain management. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 38(9), 1815–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccarrone, P., Illuzzi, A., & Inguanta, S. (2024). Does a change in the ESG ratings influence firms’ market value? Evidence from an event study. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 17(8), 340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, M. (2015). Value-enhancing capabilities of CSR: A brief review of contemporary literature. Journal of Business Ethics, 127(2), 419–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manocha, P., & Srai, J. S. (2020). Exploring environmental supply chain innovation in M&A. Sustainability, 12(23), 10105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meckling, W. H., & Jensen, M. C. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs and ownership structure. Social Science Research Network, 3(4), 205–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendiratta, A., Singh, S., Yadav, S. S., & Mahajan, A. (2023). When do ESG controversies reduce firm value in India? Global Finance Journal, 55, 100809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mili, S. A., & Hashim, F. (2023). Board attributes and firm value: The moderating role of board meeting frequency. Global Business and Management Research, 15(3), 337–352. [Google Scholar]

- Moosavi, J., Fathollahi-Fard, A. M., & Dulebenets, M. A. (2022). Supply chain disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic: Recognizing potential disruption management strategies. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 75, 102983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moursli, R. M. (2020). The effects of board independence on busy directors and firm value: Evidence from regulatory changes in Sweden. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 28(1), 23–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nekhili, M., Boukadhaba, A., Nagati, H., & Chtioui, T. (2021). ESG performance and market value: The moderating role of employee board representation. International Journal of Human Resource Management, 32(14), 3061–3087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikbakht, Z. (2024). The relationship between cash flows of operating, investments, and financing activities with the firm value. International Journal of Finance & Managerial Accounting, 9(33), 101–112. [Google Scholar]

- Olojede, P., Erin, O. A., Asiriuwa, O., & Usman, M. (2020). Audit expectation gap: An empirical analysis. Future Business Journal, 6(1), 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omer, W. K. H., Aljaaidi, K. S., & Habtoor, O. S. (2020). Board quality, audit quality and economic firm value: The case of manufactured Saudi’s listed companies. Calitatea, 21(178), 96–102. [Google Scholar]

- Osei, A. A., Yusheng, K., Casar, A. E., Tawiah, V. K., & Angelina, T. K. (2019). Collapse of big banks in Ghana: Lessons on its corporate governance. International Institute for Science, Technology, and Education, 10(10), 27–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen, L. H., Fitzgibbons, S., & Pomorski, L. (2021). Responsible investing: The ESG-efficient frontier. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 572–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piot, C., & Missonier-Piera, F. (2017). Corporate governance reform and the cost of debt financing of listed french companies. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2018). Creating shared value: How to reinvent capitalism—And unleash a wave of innovation and growth. In Managing sustainable business: An executive education case and textbook (pp. 323–346). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Priem, R., & Gabellone, A. (2024). The impact of a firm’s ESG score on its cost of capital: Can a high ESG score serve as a substitute for a weaker legal environment. Sustainability Accounting, Management and Policy Journal (Print), 15(3), 676–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, H. U., Zahid, M., & Al-Faryan, M. A. S. (2023). ESG and firm performance: The rarely explored moderation of sustainability strategy and top management commitment. Journal of Cleaner Production, 404, 136859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. J., & Yilun, L. (2021). Firm size, firm age, and firm profitability: Evidence from China. Journal of Accounting, Business & Management, 28(1), 101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A. (2021). Board independence and corporate social responsibility reporting: Mediating role of stakeholder power. Management Research Review, 44(8), 1217–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastogi, S., Singh, K., & Kanoujiya, J. (2024). Firm’s value and ESG: The moderating role of ownership concentration and corporate disclosures. Asian Review of Accounting, 32(1), 70–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Refinitiv. (2022). Environmental, social and governance (ESG) scores from refinitiv. Available online: https://www.refinitiv.com (accessed on 8 November 2024).

- Ribando, J. M., & Bonne, G. (2010). A new quality factor: Finding alpha with ASSET4 ESG data. T. Reuters. [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, S. (2006). Over-investment of free cash flow. Review of Accounting Studies, 11(2–3), 159–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, R. M., Maldonado-Guzmán, G., Madrid-Guijarro, A., & Garza-Reyes, J. A. (2022). Does circular economy affect financial performance? The mediating role of sustainable supply chain management in the automotive industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 379, 134670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenbaum, P. R., & Rubin, D. B. (1983). The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika, 70(1), 41–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasranamam, S., Arya, B., & Sud, M. (2020). Ownership structure and corporate social responsibility in an emerging market. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 37(4), 1165–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samad, S., Nilashi, M., Almulihi, A., Alrizq, M., Alghamdi, A., Mohd, S., Ahmadi, H., & Syed Azhar, S. N. F. (2021). Green supply chain management practices and impact on firm performance: The moderating effect of collaborative capability. Technology in Society, 67, 101766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samosir, F. C. (2018). Effect of cash conversion cycle, firm size, and firm age to profitability. Journal of Applied Accounting and Taxation, 3(1), 50–57. [Google Scholar]

- Samy El-Deeb, M., Ismail, T. H., & El Banna, A. A. (2023). Does audit quality moderate the impact of environmental, social and governance disclosure on firm value? Further evidence from Egypt. Journal of Humanities and Applied Social Science, 5(4), 293–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sattar, U., Javeed, S. A., & Latief, R. (2020). How audit quality affects the firm performance with the moderating role of the product market competition: Empirical evidence from Pakistani manufacturing firms. Sustainability, 12(10), 4153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipman, J. E., Swanquist, Q. T., & Whited, R. L. (2017). Propensity score matching in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 92(1), 213–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siagian, F., Siregar, S. V., & Rahadian, Y. (2013). Corporate governance, reporting quality, and firm value: Evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Accounting in Emerging Economies, 3(1), 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, D., & Delios, A. (2017). Corporate governance, board networks and growth in domestic and international markets: Evidence from India. Journal of World Business: JWB, 52(5), 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Souther, M. E. (2021). Does board independence increase firm value? Evidence from closed-end funds. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 56(1), 313–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G. C., & Johnson, M. (2016). Integrating the supply chain … 25 years on. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 46(1), 19–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudiyatno, B., Puspitasari, E., Suwarti, T., & Asyif, M. (2020). Determinants of firm value and profitability: Evidence from Indonesia. The Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 7(11), 769–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, G., Agyemang, A., Wiredu, I., & Saeed, U. F. (2023). Green innovation and sustainable products in small and medium-sized enterprises in China: The moderating and mediating roles of technology and work engagement. Environmental Engineering and Management Journal, 22(12), 2165–2176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadros, E. (2023, December 20). One in two want government to cut use of big four firms: Survey. The financial review: Australia edition. Available online: https://www.afr.com/companies/professional-services/one-in-two-want-government-to-cut-use-of-big-four-firms-survey-20231214-p5erhe (accessed on 24 April 2025).

- Thenmozhi, M., & Sasidharan, A. (2020). Does board independence enhance firm value of state-owned enterprises? Evidence from India and China. European Business Review, 32(5), 785–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, M., Tiwari, T., Sam Santhose, S., Mishra, L., Mr, R., & Sundararaj, V. (2023). Corporate social responsibility and supply chain: A study for evaluating corporate hypocrisy with special focus on stakeholders. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 28(2), 1391–1403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsang, Y. P., Fan, Y., Feng, Z. P., & Li, Y. (2024). Examining supply chain vulnerability via an analysis of ESG-Prioritized firms amid the Russian-Ukrainian conflict. Journal of Cleaner Production, 434, 139754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2017). Does ESG performance have an impact on financial performance? Evidence from Germany. Journal of Global Responsibility, 8(2), 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velte, P. (2019). The bidirectional relationship between ESG performance and earnings management—Empirical evidence from Germany. Journal of Global Responsibility, 10(4), 322–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J. (2012). Do firms’ relationships with principal customers/suppliers affect shareholders’ income? Journal of Corporate Finance, 18(4), 860–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., & Yang, Y. (2022). An empirical analysis of the supply chain flexibility using blockchain technology. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1004007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weston, P., & Nnadi, M. (2023). Evaluation of strategic and financial variables of corporate sustainability and ESG policies on corporate finance performance. Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, 13(2), 1058–1074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieland, A., Wallenburg, C. M., Juuso, T., Harri, L., & Ojala, L. (2013). The influence of relational competencies on supply chain resilience: A relational view. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management, 43(4), 300–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, C. W. Y., Lirn, T.-C., Yang, C.-C., & Shang, K.-C. (2020). Supply chain and external conditions under which supply chain resilience pays: An organizational information processing theorization. International Journal of Production Economics, 226, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S., Li, X., Du, X., & Li, Z. (2022). The impact of ESG performance on firm value: The moderating role of ownership structure. Sustainability, 14(21), 14507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z., Lin, S., Chen, T., Luo, C., & Xu, H. (2023). Does effective corporate governance mitigate the negative effect of ESG controversies on firm value? Economic Analysis and Policy, 80, 1772–1793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J. Z., Yang, H., & Chow, C. W. (2004). The determinants and characteristics of voluntary Internet-based disclosures by listed Chinese companies. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 23(3), 191–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, J., Nozawa, W., Yagi, M., Fujii, H., & Managi, S. (2019). Do environmental, social, and governance activities improve corporate financial performance? Business Strategy and the Environment, 28(2), 286–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, B., Lee, J. H., & Byun, R. (2018). Does ESG performance enhance firm value? Evidence from Korea. Sustainability, 10(10), 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X., & Xiao, K. (2022). Does ESG performance affect firm value? Evidence from a new ESG-scoring approach for Chinese enterprises. Sustainability, 14(24), 16940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zahid, R. M. A., Saleem, A., & Maqsood, U. S. (2023). ESG performance, capital financing decisions, and audit quality: Empirical evidence from Chinese state-owned enterprises. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(15), 44086–44099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L., Dou, Y., & Wang, H. (2023). Green supply chain management, risk-taking, and corporate value—Dual regulation effect based on technological innovation capability and supply chain concentration. Frontiers in Environmental Science, 11, 1096349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J. T., Sharpe, W. H., Halabi, A. K., & Song, H. (2025). ESG performance and supply chain contracts: Evidence from ASX-listed companies. In E. Koç (Ed.), Developing dynamic and sustainable supply chains to achieve sustainable development goals (p. 38). IGI Global. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable | Definition and Measurement |

|---|---|

| Firm value (FV) | Firm value is measured using accounting-based indicators: return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE). |

| ESG score | ESG performance scores derived from Asset4 ESG data, available annually since 2002. ESG data can be used as standardized scores (0–100) or raw indicators covering environmental, social, and governance dimensions, accessible in Microsoft Excel format. |

| Supply chain contracts | Binary indicator capturing the strength and clarity of ESG-related clauses in supply chain contracts. Coded 1 if robust ESG standards are explicitly stated, otherwise 0. |

| Board independence | Percentage of independent directors on the board, calculated annually. |

| Audit quality | Binary variable indicating audit quality based on auditor choice. Equals 1 if ESG disclosures were audited by Big 4 auditors (Deloitte, EY, KPMG, PwC), otherwise 0, calculated annually (2012–2021). |

| Firm size | Firm size is measured as the natural logarithm of total assets. |

| Firm age | Firm age refers to the number of years since a firm’s establishment. |

| R&D cost | R&D cost is measured as the ratio of R&D expenditure to total sales. |

| Operating cash flow | Operating cash flow = net income + non-cash expenses + changes in working capital. |

| Debit ratio | The debt ratio represents the percentage of a firm’s assets financed through debt. |

| ESG report dummy | Binary variable indicating whether a firm has published an ESG report. Equals 1 if firms publicly disclose an ESG report, otherwise 8. |

| Board meeting | This variable is measured by the number of board meetings held each year. |

| Board size | Board size is measured as the natural logarithm of the number of directors on the board. |

| Board tenure | Board tenure is measured as the average number of years a firm’s board of directors has served. |

| Variables | N | Mean | STD | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 1.ROA | 844 | 0.037 | 0.093 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2. ROE | 844 | 0.076 | 0.208 | 0.832 * | 1.000 | |||||

| 3. ESG Score | 844 | 5.268 | 2.528 | 0.030 | −0.009 | 1.000 | ||||

| 4. Supply-chain contracts | 844 | 0.552 | 0.498 | −0.087 ** | −0.088 ** | −0.123 | 1.000 | |||

| 5.Board independence | 844 | 0.102 | 0.034 | −0.086 ** | −0.062 * | 0.172 *** | −0.091 *** | 1.000 | ||

| 6.Audit quality | 844 | 0.850 | 0.358 | −0.049 | −0.050 | −0.033 | −0.093 *** | 0.020 | 1.000 | |

| 7.Firm size | 844 | 8.424 | 1.833 | −0.002 | 0.076 ** | −0.699 *** | 0.099 *** | −0.371 *** | 0.052 | 1.000 |

| 8.Firm age | 844 | 3.478 | 0.722 | 0.010 | 0.010 | −0.209 *** | 0.042 | −0.085 | 0.083 ** | 0.231 *** |

| 9.Operating cash flow | 844 | 0.095 | 0.088 | 0.548 *** | 0.411 *** | 0.092 *** | −0.045 | 0.054 | −0.087 ** | −0.194 *** |

| 10.Debt ratio | 844 | 0.038 | 0.050 | −0.187 *** | −0.105 *** | −0.035 | −0.156 *** | 0.063 * | 0.062 * | 0.107 *** |

| 11.R&D capital | 844 | 0.004 | 0.019 | 0.169 *** | 0.164 *** | −0.045 | 0.152 *** | −0.021 | −0.075 ** | −0.020 |

| 12.ESG report dummy | 844 | 0.723 | 0.448 | −0.025 | −0.015 | −0.617 *** | 0.139 *** | −0.090 *** | 0.050 | 0.473 *** |

| 13.Board meetings | 844 | 12.250 | 4.547 | −0.158 *** | −0.108 *** | −0.009 | −0.046 | 0.133 *** | 0.091 *** | 0.089 *** |

| 14.Board size | 844 | 2.009 | 0.266 | 0.040 | 0.073 ** | −0.553 *** | 0.108 *** | −0.693 *** | 0.047 | 0.724 *** |

| 15. Board tenure | 844 | 1.755 | 0.379 | 0.099 *** | 0.063 * | 0.016 | −0.166 *** | 0.026 | 0.001 | −0.099 *** |

| Variables | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

| 8.Firm age | 1.000 | |||||||||

| 9.Operating cash flow | 0.008 | 1.000 | ||||||||

| 10.Debt ratio | 0.025 | −0.194 *** | 1.000 | |||||||

| 11.R&D capital | −0.006 | 0.128 *** | −0.055 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 12.ESG report dummy | 0.158 *** | −0.055 | 0.003 | 0.005 | 1.000 | |||||

| 13.Board meetings | −0.010 | −0.097 *** | 0.111 *** | −0.084 ** | 0.101 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| 14.Board size | 0.180 *** | −0.129 *** | −0.043 | 0.043 | 0.359 *** | −0.061 * | 1.000 | |||

| 15. Board tenure | 0.028 | 0.100 *** | 0.003 | 0.114 *** | 0.003 | −0.081 ** | −0.054 |

| DV = ROA | DV = ROE | |

|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) |

| ESG Score (H1) | 0.007 ** | 0.017 ** |

| (0.015) | (0.017) | |

| Firm size | 0.010 | 0.025 * |

| (0.138) | (0.088) | |

| Firm age | −0.006 | −0.021 |

| (0.567) | (0.361) | |

| Operating cash flow | 0.338 *** | 0.587 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Debt ratio | 0.043 | 0.272 |

| (0.736) | (0.418) | |

| R&D capital | 0.403 ** | 1.202 *** |

| (0.013) | (0.001) | |

| ESG report dummy | 0.005 | 0.011 |

| (0.659) | (0.690) | |

| Board meetings | −0.000 | −0.003 |

| (0.655) | (0.173) | |

| Board size | 0.016 | 0.041 |

| (0.505) | (0.452) | |

| Board tenure | −0.015 | −0.022 |

| (0.322) | (0.531) | |

| Constant | −0.081 | −0.145 |

| (0.289) | (0.435) | |

| Year dummies | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.269 | 0.264 |

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| ESG Score | 0.006 ** | 0.012 *** | 0.014 ** | 0.025 *** |

| (0.022) | (0.000) | (0.017) | (0.000) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.029 *** | 0.043 ** | −0.062 ** | 0.068 |

| (0.007) | (0.043) | (0.013) | (0.165) | |

| ESG Score * Supply-chain contracts (H2) | −0.013 *** | −0.023 *** | ||

| (0.000) | (0.002) | |||

| Firm size | 0.010 ** | 0.006 | 0.027 ** | 0.019 * |

| (0.038) | (0.218) | (0.018) | (0.092) | |

| Firm age | −0.003 | −0.003 | −0.014 | −0.015 |

| (0.753) | (0.723) | (0.514) | (0.494) | |

| Operating cash flow | 0.316 *** | 0.332 *** | 0.539 *** | 0.569 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Debt ratio | 0.033 | 0.028 | 0.251 | 0.243 |

| (0.675) | (0.716) | (0.159) | (0.171) | |

| R&D capital | 0.440 | 0.467 | 1.280 * | 1.329 ** |

| (0.130) | (0.104) | (0.054) | (0.045) | |

| ESG report dummy | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.009 | 0.010 |

| (0.676) | (0.622) | (0.710) | (0.667) | |

| Board meetings | −0.001 | −0.000 | −0.004 * | −0.003 |

| (0.370) | (0.556) | (0.061) | (0.102) | |

| Board size | 0.013 | 0.023 | 0.034 | 0.052 |

| (0.551) | (0.283) | (0.500) | (0.296) | |

| Board tenure | −0.015 | −0.019 * | −0.023 | −0.030 |

| (0.152) | (0.072) | (0.333) | (0.210) | |

| Constant | −0.044 | −0.065 | −0.066 | −0.103 |

| (0.540) | (0.368) | (0.690) | (0.534) | |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.282 | 0.289 | 0.272 | 0.276 |

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| ESG Score | 0.005 * | 0.017 *** | 0.014 * | 0.037 *** |

| (0.078) | (0.002) | (0.051) | (0.003) | |

| Board independence | −0.574 *** | 0.175 | −0.927 ** | 0.549 |

| (0.002) | (0.654) | (0.024) | (0.543) | |

| ESG Score * Board independence (H3a) | −0.111 ** | −0.212 * | ||

| (0.041) | (0.077) | |||

| Firm size | 0.010 | 0.011 * | 0.026 * | 0.029 ** |

| (0.127) | (0.071) | (0.082) | (0.049) | |

| Firm age | −0.005 | −0.006 | −0.018 | −0.021 |

| (0.664) | (0.577) | (0.424) | (0.359) | |

| Operating cash flow | 0.334 *** | 0.338 *** | 0.579 *** | 0.588 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Debt ratio | 0.030 | 0.026 | 0.250 | 0.242 |

| (0.816) | (0.838) | (0.462) | (0.469) | |

| R&D capital | 0.486 *** | 0.481 *** | 1.345 *** | 1.335 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.004) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| ESG report dummy | 0.008 | 0.009 | 0.015 | 0.017 |

| (0.500) | (0.450) | (0.566) | (0.522) | |

| Board meetings | −0.000 | −0.000 | −0.003 | −0.003 |

| (0.821) | (0.642) | (0.233) | (0.160) | |

| Board size | −0.054 | −0.045 | −0.081 | −0.063 |

| (0.113) | (0.185) | (0.284) | (0.400) | |

| Board tenure | −0.013 | −0.011 | −0.020 | −0.015 |

| (0.354) | (0.441) | (0.566) | (0.662) | |

| Constant | 0.112 | 0.006 | 0.188 | −0.016 |

| (0.193) | (0.951) | (0.325) | (0.939) | |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.282 | 0.289 | 0.272 | 0.276 |

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| ESG Score | 0.008 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.018 *** | 0.037 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Audit quality | −0.026 ** | 0.038 | −0.052 ** | 0.072 |

| (0.015) | (0.111) | (0.031) | (0.188) | |

| ESG Score * Audit quality (H3b) | −0.012 *** | −0.023 ** | ||

| (0.003) | (0.012) | |||

| Firm size | 0.010 ** | 0.010 ** | 0.026 ** | 0.026 ** |

| (0.041) | (0.048) | (0.020) | (0.023) | |

| Firm age | −0.001 | 0.000 | −0.011 | −0.008 |

| (0.918) | (0.975) | (0.639) | (0.722) | |

| Operating cash flow | 0.330 *** | 0.312 *** | 0.569 *** | 0.534 *** |

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | |

| Debt ratio | 0.051 | 0.061 | 0.289 | 0.309 * |

| (0.515) | (0.431) | (0.106) | (0.083) | |

| R&D capital | 0.392 | 0.401 | 1.180 * | 1.197 * |

| (0.176) | (0.165) | (0.076) | (0.071) | |

| ESG report dummy | 0.005 | 0.005 | 0.011 | 0.009 |

| (0.613) | (0.670) | (0.651) | (0.700) | |

| Board meetings | −0.000 | −0.001 | −0.003 | −0.003 * |

| (0.559) | (0.428) | (0.111) | (0.077) | |

| Board size | 0.015 | 0.022 | 0.039 | 0.052 |

| (0.481) | (0.312) | (0.438) | (0.301) | |

| Board tenure | −0.016 | −0.013 | −0.025 | −0.020 |

| (0.132) | (0.202) | (0.302) | (0.404) | |

| Constant | −0.084 | −0.156 ** | −0.151 | −0.290 * |

| (0.236) | (0.037) | (0.355) | (0.091) | |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.275 | 0.284 | 0.269 | 0.275 |

| Panel A: The number of suppliers. | ||||

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| ESG Score | 0.007 *** | 0.013 *** | 0.017 *** | 0.033 *** |

| (0.003) | (0.000) | (0.002) | (0.000) | |

| Number of suppliers | 0.004 | 0.034 ** | 0.009 | 0.091 *** |

| (0.664) | (0.023) | (0.650) | (0.008) | |

| ESG Score * Number of suppliers | −0.006 ** | −0.017 *** | ||

| (0.015) | (0.004) | |||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.269 | 0.275 | 0.264 | 0.273 |

| Panel B: The number of customers. | ||||

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) |

| ESG Score | 0.006 ** | 0.008 *** | 0.014 ** | 0.017 ** |

| (0.017) | (0.008) | (0.013) | (0.018) | |

| Number of customers | −0.023 *** | −0.011 | −0.048 ** | −0.035 |

| (0.005) | (0.376) | (0.010) | (0.218) | |

| ESG Score * Number of customers | −0.003 | −0.003 | ||

| (0.207) | (0.551) | |||

| Control variables | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 765 | 765 | 765 | 765 |

| R-squared | 0.277 | 0.279 | 0.271 | 0.271 |

| Panel A: ROA regressions | |||||||

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.010 *** | 0.008 ** | 0.015 *** | 0.009 ** | 0.017 *** | 0.011 *** | 0.020 *** |

| (0.006) | (0.035) | (0.000) | (0.015) | (0.006) | (0.004) | (0.004) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.044 ** | 0.049 ** | |||||

| (0.011) | (0.045) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.016 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Board independence | −0.372 * | 0.143 | |||||

| (0.064) | (0.752) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | −0.075 | ||||||

| (0.210) | |||||||

| Audit quality | −0.028 * | 0.030 | |||||

| (0.097) | (0.427) | ||||||

| ESG score * audit quality | −0.011 * | ||||||

| (0.076) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 |

| R-squared | 0.273 | 0.289 | 0.312 | 0.279 | 0.282 | 0.281 | 0.288 |

| Panel B: ROE regressions | |||||||

| DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.023 *** | 0.017 ** | 0.031 *** | 0.020 ** | 0.036 *** | 0.023 *** | 0.040 *** |

| (0.009) | (0.035) | (0.001) | (0.015) | (0.007) | (0.007) | (0.004) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.090 ** | 0.075 | |||||

| (0.013) | (0.169) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.028 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||

| Board independence | −0.527 | 0.510 | |||||

| (0.240) | (0.624) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | −0.151 | ||||||

| (0.255) | |||||||

| Audit quality | −0.065 ** | 0.042 | |||||

| (0.044) | (0.563) | ||||||

| ESG score * audit quality | −0.019 * | ||||||

| (0.091) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 | 605 |

| R-squared | 0.282 | 0.296 | 0.311 | 0.285 | 0.287 | 0.291 | 0.296 |

| Panel A: ROA regressions | |||||||

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.006 *** | 0.005 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.005 ** | −0.004 | 0.006 *** | 0.013 *** |

| (0.002) | (0.009) | (0.000) | (0.012) | (0.302) | (0.001) | (0.000) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.025 ** | 0.015 | |||||

| (0.018) | (0.383) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.009 *** | ||||||

| (0.003) | |||||||

| Board independence | −0.131 | −0.783 *** | |||||

| (0.293) | (0.003) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | 0.108 *** | ||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||

| Audit quality | 0.007 | 0.054 *** | |||||

| (0.295) | (0.000) | ||||||

| ESG score * audit quality | −0.010 *** | ||||||

| (0.001) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 |

| R-squared | 0.979 | 0.980 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.980 | 0.979 | 0.980 |

| Panel B: ROE regressions | |||||||

| DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.007 | 0.006 | 0.013 ** | 0.007 | 0.032 *** | 0.007 | 0.027 *** |

| (0.134) | (0.165) | (0.024) | (0.134) | (0.000) | (0.115) | (0.001) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.026 | 0.035 | |||||

| (0.271) | (0.378) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.012 * | ||||||

| (0.058) | |||||||

| Board independence | 0.017 | 1.486 *** | |||||

| (0.951) | (0.002) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | −0.284 *** | ||||||

| (0.000) | |||||||

| Audit quality | 0.020 | 0.139 *** | |||||

| (0.285) | (0.001) | ||||||

| ESG score * audit quality | −0.025 *** | ||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 | 744 |

| R-squared | 0.805 | 0.805 | 0.807 | 0.805 | 0.809 | 0.805 | 0.808 |

| Panel A: The average treatment effect on the treated sample | |||||||

| DV = ROA | ATT (t-stat) | Treated group | Control group | ||||

| ESGScoreDum | 0.020 * (1.82) | 0.051 | 0.031 | ||||

| DV = ROE | ATT (t-stat) | Treated group | Control group | ||||

| ESGScoreDum | 0.070 *** (2.84) | 0.099 | 0.029 | ||||

| Panel B: ROA regressions based on the matched sample | |||||||

| DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | DV = ROA | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.008 ** | 0.006 * | 0.015 *** | 0.006 * | 0.020 *** | 0.009 *** | 0.019 *** |

| (0.012) | (0.058) | (0.001) | (0.060) | (0.002) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.039 ** | 0.063 ** | |||||

| (0.037) | (0.039) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.016 *** | ||||||

| (0.002) | |||||||

| Board independence | −0.624 *** | 0.234 | |||||

| (0.002) | (0.595) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | −0.126 ** | ||||||

| (0.036) | |||||||

| Audit quality | −0.032 * | 0.031 | |||||

| (0.062) | (0.429) | ||||||

| ESG score * audit quality | −0.011 * | ||||||

| (0.061) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 |

| R-squared | 0.272 | 0.284 | 0.301 | 0.288 | 0.295 | 0.280 | 0.288 |

| Panel C: ROE regressions based on the matched sample | |||||||

| DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | DV = ROE | |

| Variables | (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | (7) |

| ESG score | 0.020 ** | 0.016 ** | 0.032 *** | 0.016 ** | 0.044 *** | 0.022 *** | 0.039 *** |

| (0.010) | (0.033) | (0.001) | (0.033) | (0.001) | (0.006) | (0.003) | |

| Supply-chain contracts | −0.077 ** | 0.119 * | |||||

| (0.040) | (0.079) | ||||||

| ESG score * supply-chain contracts | −0.031 *** | ||||||

| (0.004) | |||||||

| Board independence | −1.111 ** | 0.660 | |||||

| (0.014) | (0.512) | ||||||

| ESG score * board independence | −0.260 ** | ||||||

| (0.046) | |||||||

| Audit quality | −0.065 ** | 0.046 | |||||

| (0.045) | (0.531) | ||||||

| ESG Score * Audit quality | −0.020 * | ||||||

| (0.076) | |||||||

| Controls | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Year dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Industry dummies | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES | YES |

| Observations | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 | 644 |

| R-squared | 0.274 | 0.282 | 0.295 | 0.283 | 0.289 | 0.280 | 0.285 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhou, J.; Sharpe, W.H.; Halabi, A.K.; Song, H.; Colombage, S. Unlock Your Firm Value with ESG Performance? Evidence from ASX-Listed Companies. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050247

Zhou J, Sharpe WH, Halabi AK, Song H, Colombage S. Unlock Your Firm Value with ESG Performance? Evidence from ASX-Listed Companies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):247. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050247

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhou, Jingyan, Wen Hua Sharpe, Abdel K. Halabi, Helen Song, and Sisira Colombage. 2025. "Unlock Your Firm Value with ESG Performance? Evidence from ASX-Listed Companies" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050247

APA StyleZhou, J., Sharpe, W. H., Halabi, A. K., Song, H., & Colombage, S. (2025). Unlock Your Firm Value with ESG Performance? Evidence from ASX-Listed Companies. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 247. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050247