The Effect of Different Saving Mechanisms in Pension Saving Behavior: Evidence from a Life-Cycle Experiment

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Background Literature

2.1. Retirement Planning and Bounded Rationality

2.2. Saving Decisions in Different Environments

2.3. Saving Decisions Under Stochastic Income

3. Hypotheses

3.1. Hypothesis I: Undersaving/Overconsumption

3.2. Hypothesis II: Income Uncertainty

3.3. Hypothesis III: Savings Mechanisms

4. Experimental Design

4.1. The Consumption-Saving Task

4.1.1. Consumption Utility

4.1.2. Loss Aversion

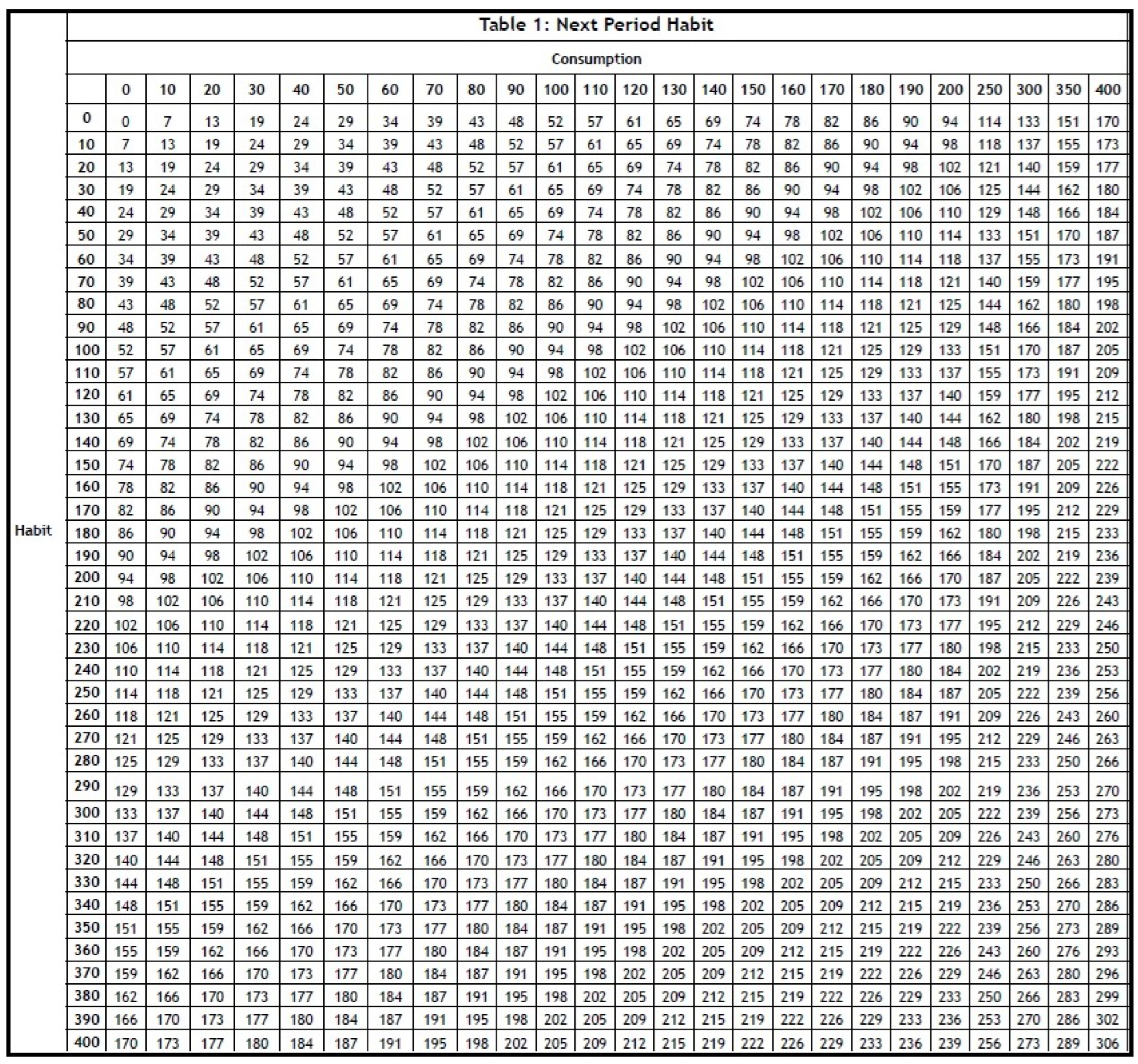

4.1.3. Habit Formation

4.2. Treatment Conditions

4.2.1. Baseline

4.2.2. Deterministic vs. Stochastic Income

4.2.3. Saving Mechanisms

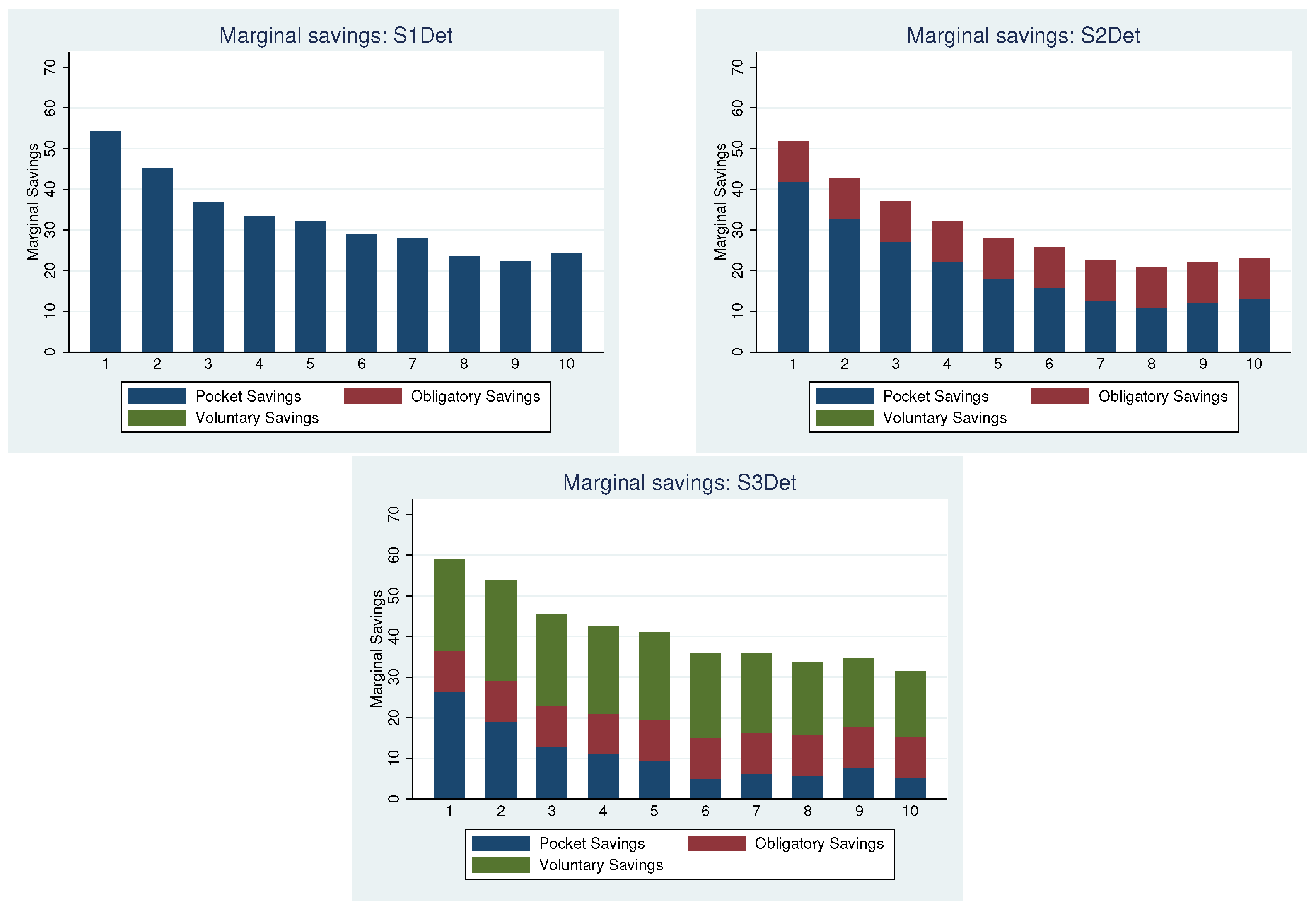

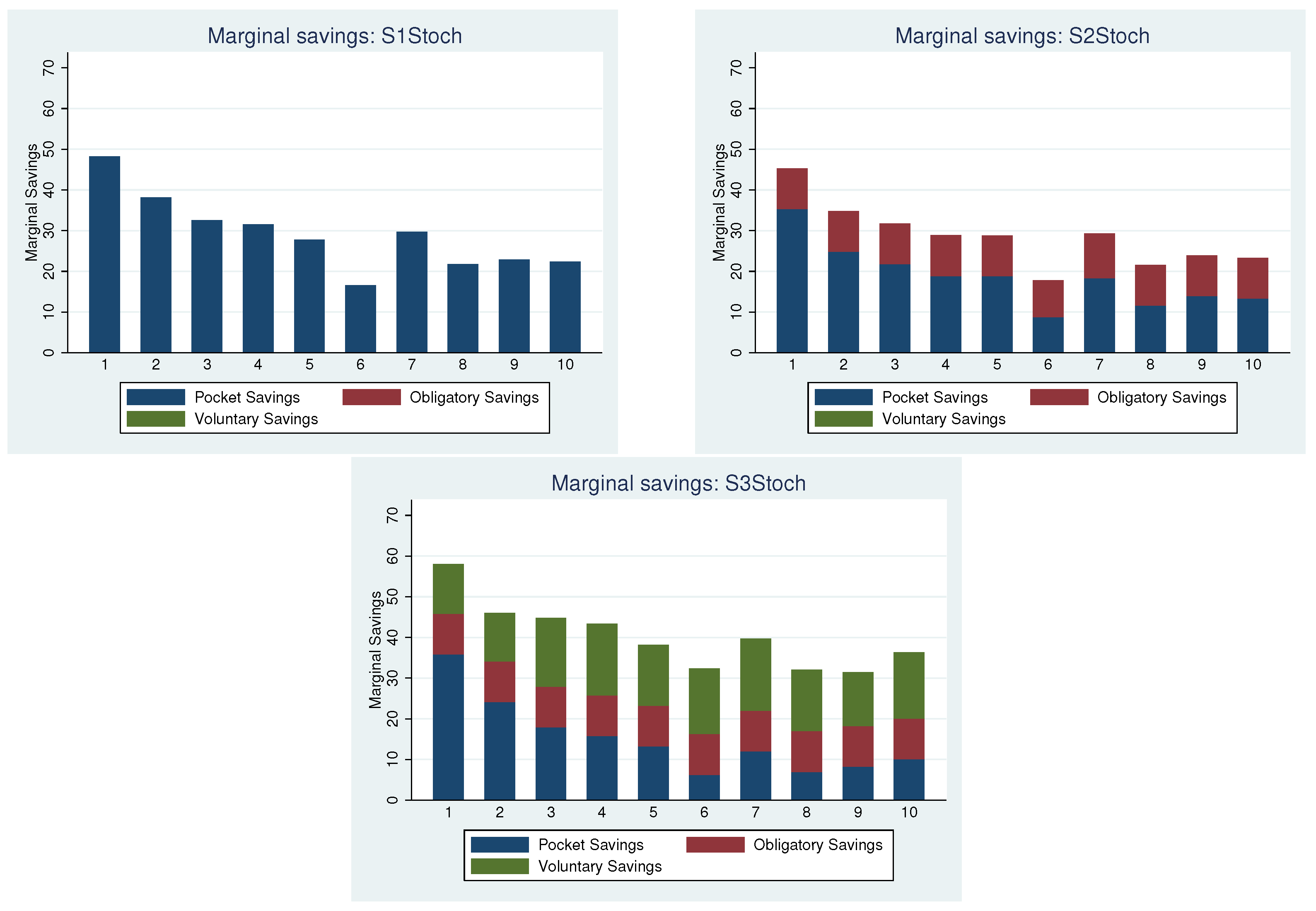

- Setting 1 (S1): All unspent income automatically becomes pocket savings (), which can be accessed at any time. Total retirement savings equal .

- Setting 2 (S2): Participants must contribute 10% of their work life income each period to an obligatory pension savings account (), which cannot be accessed until retirement starts in Period 11. During the working phase, obligatory savings increase by 0.1 × per period. Participants can still accumulate pocket savings by spending less than their disposable income, i.e., up to 0.9 × per period. At retirement, total savings are the sum of pocket and obligatory savings: .

- Setting 3 (S3): In addition to the obligatory and pocket saving mechanisms from S2, participants can also make voluntary pension savings (). Like obligatory savings, voluntary savings cannot be accessed before retirement. There is no interest advantage for holding funds in obligatory or voluntary accounts compared to pocket savings. Hence, total retirement savings are the sum of all three accounts: .

4.3. Implementation

5. Results

5.1. Sample Characteristics

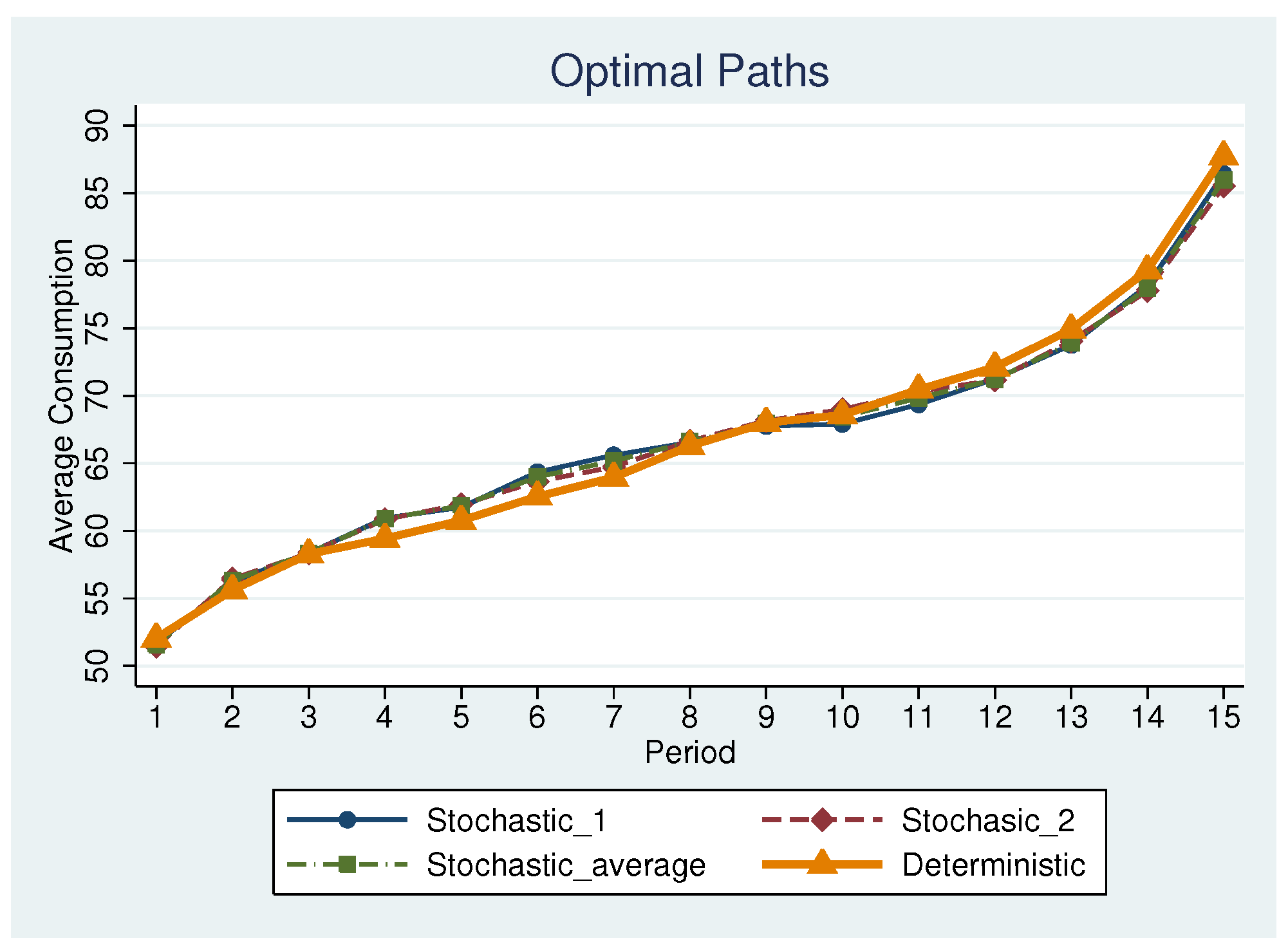

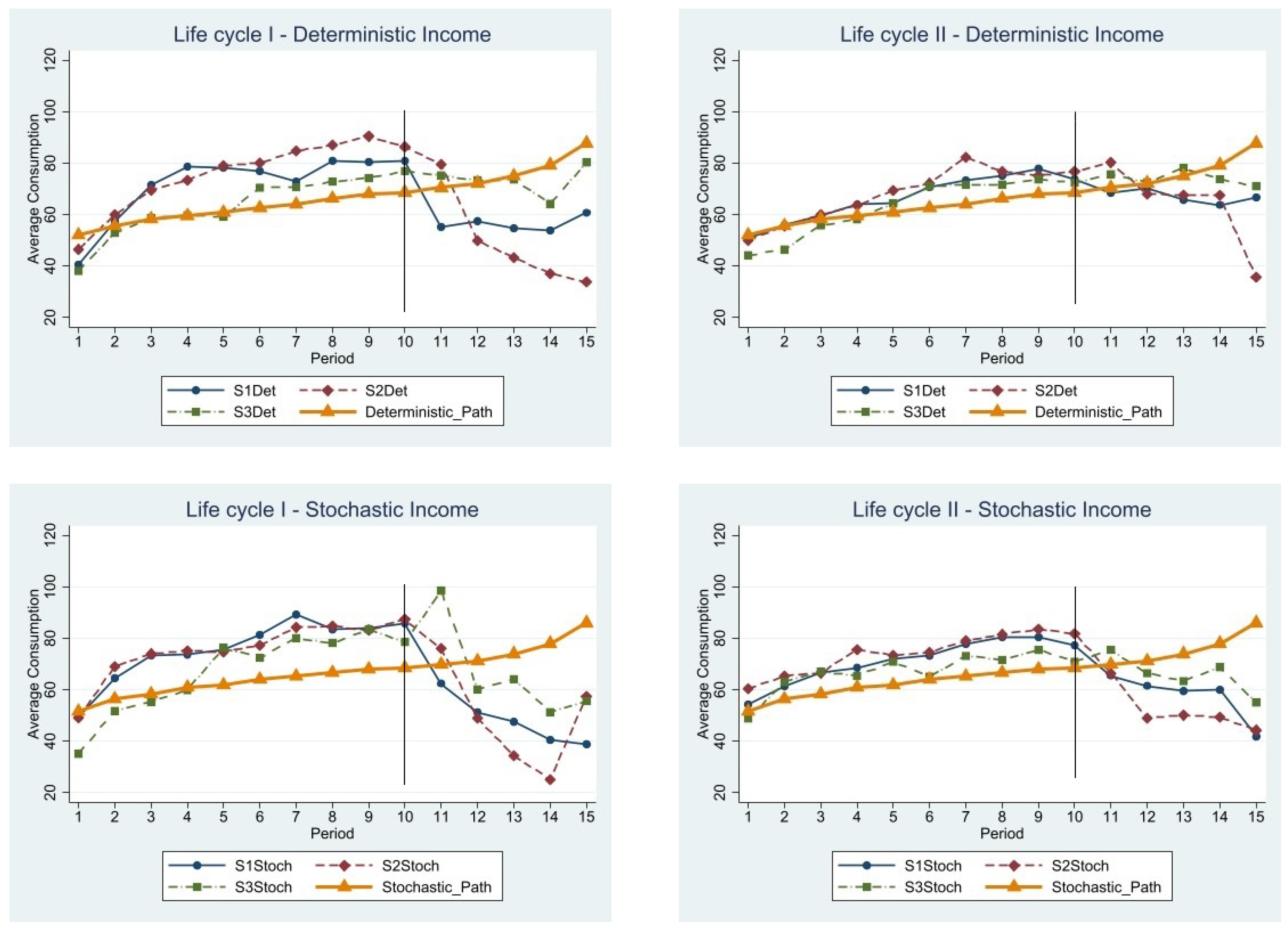

5.2. Hypotheses Ia and Ib: Undersaving/Overconsumption

5.3. Hypotheses IIa and IIb: Income Uncertainty

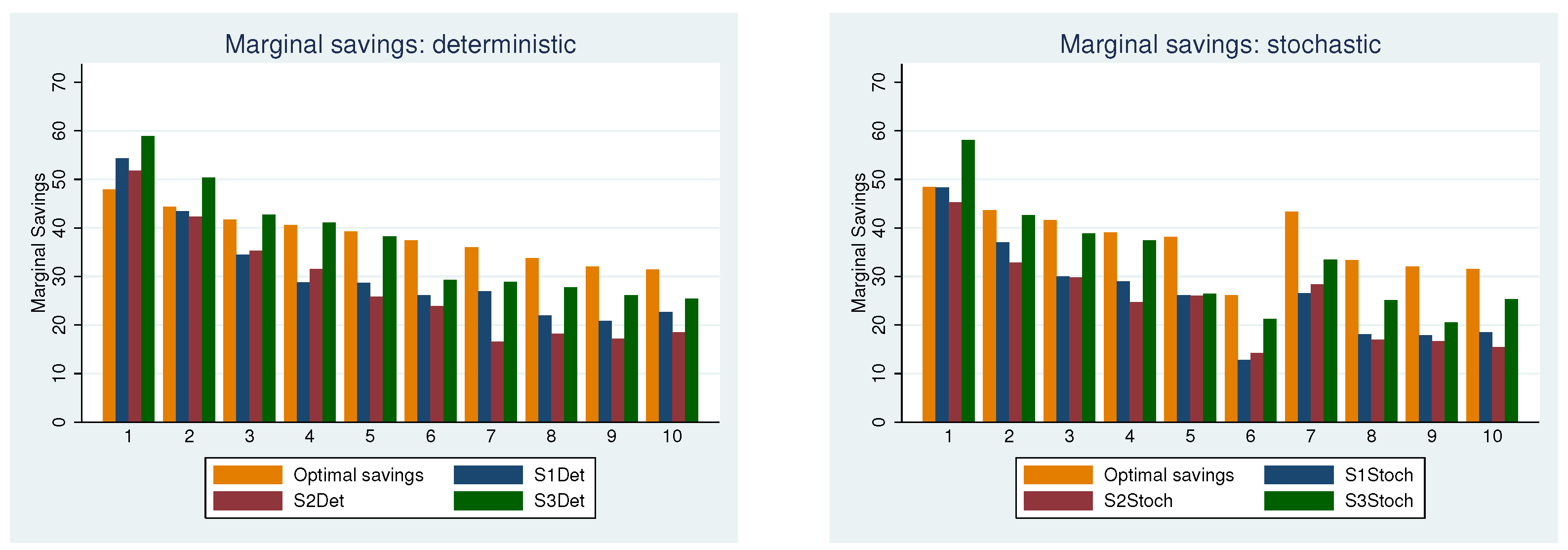

5.4. Hypotheses IIIa and IIIb: Pension Systems/Saving Mechanisms

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Formal Considerations

Appendix B. Instructions

Appendix C. Descriptive Statistics of Income Paths and Utility per Treatment

| Treatment/Period | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | Sum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deterministic | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 1000 |

| Stochastic I | 120 | 80 | 100 | 120 | 80 | 80 | 100 | 80 | 120 | 120 | 1000 |

| Stochastic II | 80 | 120 | 100 | 80 | 120 | 100 | 120 | 120 | 80 | 80 | 1000 |

| Mean | St.dev | Min | Max | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LC1 | S1Det | 1074.64 | 188.56 | 673 | 1314 |

| S2Det | 1090.07 | 126.61 | 874 | 1325 | |

| S3Det | 1118.17 | 132.22 | 798 | 1317 | |

| S1Stoch | 1070.83 | 166.12 | 750 | 1317 | |

| S2Stoch | 1036.17 | 137.03 | 723 | 1280 | |

| S3Stoch | 969.2 | 301.91 | 86 | 1323 | |

| LC2 | S1Det | 1163.4 | 131.64 | 888 | 1317 |

| S2Det | 1160.43 | 126.46 | 778 | 1323 | |

| S3Det | 1174.17 | 99.12 | 991 | 1319 | |

| S1Stoch | 1101.6 | 151.7 | 773 | 1324 | |

| S2Stoch | 1110.33 | 140.56 | 725 | 1316 | |

| S3Stoch | 1107.03 | 160.83 | 821 | 1323 |

Appendix D. Statistical Tests of Saving Mechanisms

| Life Cycle I | Life Cycle II | Treat. | Life Cycle I | Life Cycle II | Treat. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 282 | 335 | S1Det | 240 | 288 | S1Stoch | |

| 143 | 219 | S2Det | 142 | 159 | S2Stoch | |

| 66 | 63 | S3Det | 91 | 63 | S3Stoch | |

| Obligatory | - | - | S1Det | - | - | S1Stoch |

| 100 | 100 | S2Det | 100 | 100 | S2Stoch | |

| 100 | 100 | S3Det | 100 | 100 | S3Stoch | |

| Voluntarily | - | - | S1Det | - | - | S1Stoch |

| - | - | S2Det | - | - | S2Stoch | |

| 200 | 208 | S3Det | 138 | 166 | S3Stoch |

| Deterministic Income | Stochastic Income | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1/S2 | S2/S3 | S1/S2 | S2/S3 | |

| Total Savings | 0.15 | 0.02 | 0.46 | 0.00 |

| S1 | S2 | S3 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Savings | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.34 |

| Pocket Savings | 0.20 | 0.11 | 0.73 |

| Voluntary Savings | - | - | 0.17 |

| 1 | We assume that all participants have the same “lifetime”, so that we could compare their savings behavior across the same time span. If T would vary from participant to participant, the comparison of experimental results would be rather difficult. |

| 2 | Appendix A shows that the habit formation function is increasing in habit and consumption, but at a decreasing speed. |

| 3 | In previous studies, ranges from 0.1 (Fehr & Zych, 1998) to 0.7 (A. L. Brown et al., 2009). We follow Carroll (2000) in choosing an intermediate value of = 0.5, assuming equal contribution of previous period habit and previous period consumption to the new habit value. |

| 4 | See, for example, Beshears et al. (2015b) for an analysis of the pension systems in six developed countries. |

| 5 | For stochastic income, we show the average of the optimal consumption paths for Path 1 and Path 2. |

| 6 | For the comparison of observed and optimal paths, we use the average savings across the two life cycles. |

| 7 | Descriptive statistics are provided in Appendix C. |

| 8 | All regressions are checked for multicollinearity and corrected for heteroscedasticity by using robust standard errors. |

| 9 | These visual conclusions are supported by the results of a Mann–Whitney U-test, see Table A4 and Table A5 in Appendix D. We compare whether (1) pocket savings; (2) the sum of pocket and voluntary savings; and (3) total savings differ across treatments. |

References

- Agnew, J. R., Anderson, L. R., Gerlach, J. R., & Szykman, L. R. (2008). Who chooses annuities? An experimental investigation of the role of gender, framing, and defaults. American Economic Review, 98(2), 418–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnew, J. R., Anderson, L. R., & Szykman, L. R. (2015). An experimental study of the effect of market performance on annuitization and equity allocations. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 16(2), 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, N., Karlan, D., & Yin, W. (2006). Tying Odysseus to the Mast: Evidence from a commitment savings product in the philippines. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 121(2), 635–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bachmann, K., Lot, A., Xu, X., & Hens, T. (2023). Experimental research on retirement decision-making: Evidence from replications. Journal of Banking & Finance, 152, 106851. [Google Scholar]

- Ballinger, T. P., Hudson, E., Karkoviata, L., & Wilcox, N. T. (2011). Saving behavior and cognitive abilities. Experimental Economics, 14(3), 349–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballinger, T. P., Palumbo, M. G., & Wilcox, N. T. (2003). Precautionary saving and social learning across generations: An experiment. The Economic Journal, 113(490), 920–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benartzi, S., & Thaler, R. H. (2013). Behavioral economics and the retirement savings crisis. Science, 339(6124), 1152–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Harris, C., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Sakong, J. (2015a). Self control and commitment: Can decreasing the liquidity of a savings account increase deposits? (Working Paper No. 21474). National Bureau of Economic Research. Available online: http://www.nber.org/papers/w21474 (accessed on 15 January 2025).

- Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Harris, C., Laibson, D., Madrian, B. C., & Sakong, J. (2020). Which early withdrawal penalty attracts the most deposits to a commitment savings account? Journal of Public Economics, 183, 104144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beshears, J., Choi, J. J., Hurwitz, J., Laibson, D., & Madrian, B. C. (2015b). Liquidity in retirement savings systems: An international comparison. American Economic Review, 105(5), 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowman, D., Minehart, D., & Rabin, M. (1999). Loss aversion in a consumption–savings model. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 38(2), 155–178. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A. L., Chua, Z. E., & Camerer, C. F. (2009). Learning and visceral temptation in dynamic saving experiments. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 124(1), 197–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, J. R., Kling, J. R., Mullainathan, S., & Wrobel, M. V. (2008). Why don’t people insure late-life consumption? A framing explanation of the under-annuitization puzzle. American Economic Review, 98(2), 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C. F., & Ho, T.-H. (1994). Violations of the betweenness axiom and nonlinearity in probability. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 8(2), 167–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, E., & Hey, J. D. (2004). The effect of unemployment on consumption: An experimental analysis. The Economic Journal, 114(497), 660–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Card, D., & Ransom, M. (2011). Pension plan characteristics and framing effects in employee savings behavior. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93(1), 228–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C. D. (2000). Solving consumption models with multiplicative habits. Economics Letters, 68(1), 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, C. D., Overland, J., & Weil, D. N. (2000). Saving and growth with habit formation. American Economic Review, 90(3), 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, D. L., Schonger, M., & Wickens, C. (2016). oTree—An open-source platform for laboratory, online, and field experiments. Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Finance, 9, 88–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleave, B., Nikiforakis, N., & Slonim, R. (2013). Is there selection bias in laboratory experiments? The case of social and risk preferences. Experimental Economics, 16(3), 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Conway, A. R., Kane, M. J., Bunting, M. F., Hambrick, D. Z., Wilhelm, O., & Engle, R. W. (2005). Working memory span tasks: A methodological review and user’s guide. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 12(5), 769–786. [Google Scholar]

- Crosetto, P., & Filippin, A. (2013). The “bomb” risk elicitation task. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 47, 31–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidoff, T., Brown, J. R., & Diamond, P. A. (2005). Annuities and individual welfare. American Economic Review, 95(5), 1573–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J. (2008). Macroeconomics: A survey of laboratory research. Handbook of Experimental Economics, 2, 1–90. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, J., & Li, Y. (2019). Lifecycle consumption under different income profiles: Evidence and theory. Journal of Economic Dynamics and Control, 104, 74–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duffy, J., & Orland, A. (2023). Liquidity constraints, income variance, and buffer stock savings: Experimental evidence [Unpublished manuscript]. University of California. Irvine, CA, USA.

- Ebbinghaus, B. (2021). Inequalities and poverty risks in old age across Europe: The double-edged income effect of pension systems. Social Policy & Administration, 55(3), 440–455. [Google Scholar]

- Falk, A., & Heckman, J. J. (2009). Lab experiments are a major source of knowledge in the social sciences. Science, 326(5952), 535–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatás, E., Lacomba, J. A., Lagos, F., & Moro-Egido, A. I. (2013). An experimental test on dynamic consumption and lump-sum pensions. SERIEs, 4(4), 393–413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Zych, P. K. (1998). Do addicts behave rationally? The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 100(3), 643–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feltovich, N., & Ejebu, O.-Z. (2014). Do positional goods inhibit saving? Evidence from a life-cycle experiment. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 107, 440–454. [Google Scholar]

- Fenig, G., & Petersen, L. (2024). Dynamic optimization meets budgeting: Unraveling financial complexities. NBER Working Paper, 32821, 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Fréchette, G. R. (2015). Laboratory experiments: Professionals versus students. In J. H. Kagel, & A. E. Roth (Eds.), The handbook of experimental economics (Vol. 2, pp. 435–480). Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, M. (1957). A theory of the consumption function. National Bureau of Economic Research, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Fuhrer, J. C., & Klein, M. W. (1998). Risky habits: On risk sharing, habit formation, and the interpretation of international consumption correlations. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Gechert, S., & Siebert, J. (2022). Preferences over wealth: Experimental evidence. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 200, 1297–1317. [Google Scholar]

- Gourinchas, P.-O., & Parker, J. A. (2002). Consumption over the life cycle. Econometrica, 70(1), 47–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, C., & Laibson, D. (2001). Dynamic choices of hyperbolic consumers. Econometrica, 69(4), 935–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hey, J. D., & Dardanoni, V. (1988). Optimal consumption under uncertainty: An experimental investigation. The Economic Journal, 98(390), 105–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinrichs, K. (2021). Recent pension reforms in Europe: More challenges, new directions. An overview. Social Policy & Administration, 55(3), 409–422. [Google Scholar]

- Karlan, D., McConnell, M., Mullainathan, S., & Zinman, J. (2016). Getting to the top of mind: How reminders increase saving. Management Science, 62(12), 3393–3411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kappes, H. B., Campbell, R., & Ivchenko, A. (2023). Scarcity and predictability of income over time: Experimental games as a way to study consumption smoothing. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 8(4), 391–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lally, P., Van Jaarsveld, C. H., Potts, H. W., & Wardle, J. (2010). How are habits formed: Modelling habit formation in the real world. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lusardi, A. (1999). Information, expectations, and savings for retirement. Behavioral Dimensions of Retirement Economics, 81, 115. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall, A. (2005). From Principles of Economics. In Readings in the economics of the division of labor: The classical tradition (pp. 195–215). World Scientific. [Google Scholar]

- Meissner, T. (2016). Intertemporal consumption and debt aversion: An experimental study. Experimental Economics, 19(2), 281–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modigliani, F., & Brumberg, R. (1954). Utility analysis and the consumption function: An interpretation of cross-section data. Post-Keynesian economics, 1, 388–436. [Google Scholar]

- Rha, J.-Y., Montalto, C. P., & Hanna, S. D. (2006). The effect of self-control mechanisms on household saving behavior. Journal of Financial Counseling and Planning, 17(2). [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez, C., & Saavedra, J. (2015). Nudging youth to develop savings habits: Experimental evidence using SMS messages. In CESR-schaeffer working paper (2015–2018). Washington University in St. Louis. [Google Scholar]

- Rudolph, H. P. (2016). Building voluntary pension schemes in emerging economies. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2895485 (accessed on 10 April 2025).

- Skinner, J. (1988). Risky income, life cycle consumption, and precautionary savings. Journal of Monetary Economics, 22(2), 237–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. (1994). Psychology and savings policies. The American Economic Review, 84(2), 186–192. [Google Scholar]

- Tversky, A., & Fox, C. R. (1995). Weighing risk and uncertainty. Psychological Review, 102(2), 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, G., & Gonzalez, R. (1996). Curvature of the probability weighting function. Management Science, 42(12), 1676–1690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeldes, S. P. (1989). Optimal consumption with stochastic income: Deviations from certainty equivalence. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 104(2), 275–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Session | Treatment | Income per Period (ECU) | Setting | Pocket Savings | Obligatory Savings | Voluntary Savings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | S1Det | always 100 | 1 | + | ||

| 2 | S2Det | always 100 | 2 | + | + | |

| 3 | S3Det | always 100 | 3 | + | + | + |

| 4 | S1Stoch | 80, 100 or 120 | 1 | + | ||

| 5 | S2Stoch | 80, 100 or 120 | 2 | + | + | |

| 6 | S3Stoch | 80, 100 or 120 | 3 | + | + | + |

| Parameter | Description | Fraction | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female/Male | 61%/39% | 0.51 |

| Education | High School/Bachelor/Master/PhD/Other | 3%/50%/35%/11%/1% | 0.40 |

| Age | Below 20/20–25/25–30/Above 30 | 3%/56%/28%/13% | 0.13 |

| Cognitive abilities | Fewer than 4 correct answers/4–8/8–16 | 1%/13%/86% | 0.39 |

| Background | No /A bit/Some/Sufficient | 89%/8%/1%/2% | 0.64 |

| Task Understanding | None correct/All Correct | 18%/82% | 0.32 |

| Deterministic Income | Stochastic Income | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S1Det | S2Det | S3Det | Opt | S1Stoch | S2Stoch | S3Stoch | Opt | |

| Total | 308 | 281 | 369 | 384 | 264 | 250 | 329 | 379 |

| Std. Dev. | 10.63 | 11.99 | 11.42 | 5.39 | 10.55 | 9.73 | 11.70 | 7.03 |

| Deterministic Income | Stochastic Income | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Test | Comparison | S1Det | S2Det | S3Det | S1Stoch | S2Stoch | S3Stoch |

| Mann–Whitney U | Observed vs. Optimal | 0.07 | 0.00 | 0.63 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.02 |

| Wilcoxon-Signed-Rank | Life cycle I vs. II | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.17 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.04 |

| Dependent Variable: | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Points I | Total Points II | Δ Total PointsI,II | ||||

| (1) | (2) | (3) | (4) | (5) | (6) | |

| Constant | 1111.259 *** | 948.928 *** | 1162.206 *** | 1096.978 *** | 50.956 ** | 148.050 *** |

| (29.491) | (66.566) | (21.347) | (51.644) | (20.441) | (54.061) | |

| Stochastic | −70.925 ** | −70.772 *** | −59.611 *** | −61.741 *** | 11.314 | 9.031 |

| (28.382) | (27.291) | (20.477) | (19.770) | (21.262) | (20.837) | |

| Setting 2 | −12.671 | −28.050 | 2.983 | −12.389 | 15.654 | 15.661 |

| (29.591) | (30.106) | (25.719) | (24.730) | (21.980) | (21.997) | |

| Setting 3 | −32.104 | −45.677 | 8.199 | −3.924 | 40.304 | 41.753 |

| (39.313) | (37.242) | (25.829) | (24.497) | (28.241) | (27.907) | |

| Logic | 15.134 *** | 8.996 ** | −6.137 | |||

| (5.311) | (3.678) | (4.215) | ||||

| Female | −41.167 | −67.969 *** | −26.801 | |||

| (29.121) | (20.213) | (22.920) | ||||

| Observations | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 |

| R2 | 0.032 | 0.101 | 0.048 | 0.133 | 0.015 | 0.043 |

| Dependent Variable: | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Points I | Total Points II | |||

| Constant | 1253.44 *** | 1136.03 *** | 1207.71 *** | 1128.50 *** |

| (33.164) | (74.812) | (27.118) | (58.04) | |

| S3_Deterministic | 46.38 ** | 37.98 * | 24.75 | 11.90 |

| (20.47) | (20.39) | (20.85) | (20.42) | |

| St.deviation_marginal savings | −10.91 *** | −10.44 *** | −5.106 *** | −5.20 *** |

| (−1.91) | (2.04) | (1.56) | (1.54) | |

| Logic | 8.92 * | 9.20 ** | ||

| (4.84) | (3.80) | |||

| Female | −9.99 | −60.73 *** | ||

| (26.84) | (19.92) | |||

| N | 175 | 175 | 175 | 175 |

| R-squared | 0.293 | 0.311 | 0.084 | 0.161 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Angerer, M.; Hanke, M.; Shakina, E.; Szymczak, W. The Effect of Different Saving Mechanisms in Pension Saving Behavior: Evidence from a Life-Cycle Experiment. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050240

Angerer M, Hanke M, Shakina E, Szymczak W. The Effect of Different Saving Mechanisms in Pension Saving Behavior: Evidence from a Life-Cycle Experiment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(5):240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050240

Chicago/Turabian StyleAngerer, Martin, Michael Hanke, Ekaterina Shakina, and Wiebke Szymczak. 2025. "The Effect of Different Saving Mechanisms in Pension Saving Behavior: Evidence from a Life-Cycle Experiment" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 5: 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050240

APA StyleAngerer, M., Hanke, M., Shakina, E., & Szymczak, W. (2025). The Effect of Different Saving Mechanisms in Pension Saving Behavior: Evidence from a Life-Cycle Experiment. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(5), 240. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18050240