1. Introduction

Personal financial management especially can be a significant factor leading to sound decision-making processes and carrying a general postfix to socio-economic stability. It has a unique and central role in enhancing the capacity of individuals for managing resources and in providing the necessary tools for sustainable planning for the future and dealing with the complexities of the financial environment (

OECD, 2022).

According to research conducted by

OECD (

2022) on financial literacy in 39 countries, it was found that there is a lack of financial knowledge, financial attitudes, and financial behavior in marginalized populations especially. This shows the need for interventions, particularly to close the above gaps where they exist. In addition,

Roy and Patro (

2022) noted that the COVID-19 pandemic cast light on the gender gap in financial services due to socio-economic and cultural issues, thus highlighting the importance of women’s financial inclusion and sustainable development.

Recent studies also highlight the relationship between cognition and essential topics like financial access, decision, and sustainability. “Education”, “Gender”, and “Access to financial system” were found to determine financial literacy by

Ahmad et al. (

2023) and

Zaimovic et al. (

2023). Their studies support the premise of improving consumers’ financial literacy and financial literacy self-efficacy through digital financial literacy education, especially for the female populace. In addition,

Goyal and Kumar (

2020) notice new trends in financial literacy including digital finance and financial literacy among women, which provide information on areas that still require more attention in terms of research and policy-making.

Financial literacy is increasingly recognized as a critical component of economic empowerment, particularly in developing countries where financial systems are often underdeveloped and access to financial services is limited. The concept encompasses a range of skills and knowledge necessary for individuals to make informed financial decisions, manage financial resources effectively, and navigate complex financial products and services. However, significant disparities exist in financial literacy levels, particularly between genders. Research indicates that women in developing countries often exhibit lower financial literacy compared to their male counterparts, a trend that has profound implications for their economic agency and empowerment (

Atkinson & Messy, 2012;

Lusardi & Mitchell, 2011).

The gender gap in financial literacy can be attributed to various socio-economic factors, including educational attainment, cultural norms, and access to financial resources. Studies have shown that women are less likely to engage in financial education programs and may lack confidence in their financial knowledge, which further exacerbates the gap (

OECD, 2017). For instance, the OECD/INFE survey highlighted that in 19 out of 30 countries, women demonstrated lower financial knowledge than men, suggesting that efforts to enhance financial literacy must be gender sensitive to effectively address these disparities (

OECD, 2017).

Moreover, the implications of financial literacy extend beyond individual financial decision-making; they influence broader economic outcomes, including household financial stability and overall economic growth in developing regions. As women often play a crucial role in household financial management, improving their financial literacy can lead to better financial outcomes not only for themselves but also for their families and communities (

Ghosh & Vinod, 2017).

A literature review shows that, in terms of financial literacy, men are found to have relatively a higher literacy level than women across the globe, men obtained about four points higher than women on established tests in the financial literacy domain and that no country showed women performing better than men in the tests. This seems more so the case in developing countries where socio-economic factors compound the areas of disparity.

According to the literature based in Latin America and the Caribbean, women experience social constraints to financial literacy because of cultural norms and lack of education. For instance, research carried out in Brazil showed that while only 36% of female participants responded to basic financial quiz questions, 48% of males could answer (

Sarpong-Kumankoma et al., 2023). In addition, according to the latest World Bank data, the female labor force employment rate is still found to be lower than that of males with lower financial literacy (

World Bank, 2021). Altogether, these results underscore the palpable call to apply series to raise the level of knowledge regarding finances for women.

Like in many other countries, this study established that the gender difference in financial literacy exists in several Asian nations. A study conducted in India revealed that only 27% of women could be counted as financially literate compared to 50% of men (

Atkinson & Messy, 2012). Cultural factors including stereo schemata in decision-making roles reserved for women depress financial education among females. Thirdly, limited mobility and access to information mean that woman will also lack adequate knowledge to enhance their level of financial literacy (

OECD, 2020). This situation highlights the need for enhancing acceptability of financial resources for women.

Research carried out in Africa revealed that men are more financially literate than women across the continent. An analysis of a cross-sectional research survey in Ghana found out that 45% of males had an acceptable level of financial literacy, while the figure was 30% in females (

Sarpong-Kumankoma et al., 2023). This gap can be attributed to socio-cultural factors, which put more expectations on men in so far as financial decisions are concerned and restrain women’s access to education. In addition, a recent survey revealed that women in the sub-Saharan region are 33% less likely to save or invest than men. A total of 35% of male participants said they had a savings account while only 23% of female participants had the same (

OECD, 2020).

The results reported in this paper further confirm that women in developing nations of Latin America and the Caribbean, Asia, and Africa remain financially illiterate compared to their male counterparts. Both these gaps should be dealt with urgently as a way of empowering more women to take up economic activities and as a way of achieving inclusive development. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify, appraise, and summarize the literature on gender differences in financial literacy in developing countries, the reasons for such disparities, the consequences for women’s economic agency, and ways of improving financial literacy among women.

3. Literature Review

Financial literacy (FL) is a crucial driver of economic well-being, particularly in developing countries where financial inclusion remains a challenge. While numerous studies explore the relationship between FL, gender disparities, and economic empowerment, contradictions and research gaps persist. This review critically examines key contributions from

Van Rooij et al. (

2011),

Grohmann (

2018), and

Blake (

2022), identifying limitations and areas for further inquiry.

Financial literacy is often linked to financial inclusion and poverty reduction, yet disparities between men and women remain.

Kasozi and Makina (

2021) found that men in Uganda exhibit higher financial inclusion rates despite financial literacy interventions targeting both genders. However, their study does not sufficiently address structural barriers such as restrictive financial policies and cultural norms that hinder women’s access to financial services. Addressing these barriers may require more than just education; policy reforms and gender-sensitive financial products must also be prioritized.

Research consistently shows that women have lower financial literacy levels than men, leading to poorer financial outcomes (

Klapper et al., 2012) While socio-cultural norms and limited financial education are often cited as primary causes, these explanations overlook psychological factors such as lower financial confidence among women (

OECD, 2020). Addressing this requires interventions that build confidence alongside financial knowledge.

Van Rooij et al. (

2011) found that higher FL improves retirement planning in Dutch households. However, this assumption may not hold in developing economies, where informal labor markets and weak pension systems limit the effectiveness of financial planning. Similarly,

Blake (

2022) highlights women’s lag in retirement preparedness but does not fully explore how social security policies could mitigate this gap. Future research should focus on integrating financial literacy with policy interventions to ensure tangible economic benefits.

While

Klapper et al. (

2012) advocate for gender-sensitive financial education, education alone may not be sufficient.

Grohmann (

2018) highlights the need for policy frameworks to support financial literacy but fails to address how financial institutions often design products that do not align with women’s needs. Without structural changes such as wage equity, improved banking accessibility, and financial policies tailored to women, financial literacy alone may not bridge the gender gap.

Despite extensive research on financial literacy and gender disparities, gaps remain in understanding how FL translates into actual economic empowerment for women. While education is critical, it must be coupled with broader policy and institutional reforms. Future studies should move beyond individual-level financial literacy interventions and focus on systemic solutions that enhance women’s financial inclusion and long-term economic security.

3.1. Theoretical Review

In the past, financial literacy has proved to be critical in economic opportunities, especially in growth-sensitive economies where financial structures are comparatively less developed and basic financial services are still a dream for many. This theoretical research is an attempt to discuss the theoretical explanations of why gender differences exist in financial literacy, with a focus on the socio-economic determinants and consequences for women’s economic empowerment.

3.1.1. Socialization Theory

Edward Alsworth Ross (1866–1951) was a prominent American sociologist who contributed significantly to the development of sociological thought in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His work on socialization theory, particularly in his 1896 writings, laid the groundwork for understanding how individuals are integrated into society and how societal norms and values are transmitted across generations.

This theory is probably the most important when explaining the differences in financial literacy between males and females. Overall, the studies show that the so-called roles and norms given to both boys and girls from their childhood influence, their financial literacy, and financial self-efficacy. For instance, girls are brought up in a culture that requires them to be less assertive in issues to do with money; they, therefore, tend to lack self-efficacy with regard to their ability to handle money (

Drolet, 2016). These implications can be long term as documented by earlier research where women, particularly those in the developing world, are found to be less financially savvy than men. According to the results of the OECD/INFE study, women showed less financial literacy than men in 19 of the 30 countries studied (

OECD, 2017). As such, these findings highlight the importance of developing intercultural gender-sensitive approaches to diagnose the barriers to financial management knowledge and to promote females’ assertiveness from an early age.

3.1.2. Human Capital Theory

Human capital theory, pioneered by Gary Becker in his groundbreaking 1964 book Human Capital: A Theoretical and Empirical Analysis, redefined how we understand the value of education, skills, and health in economic terms. At its core, the theory posits that individuals, firms, and societies can invest in people much like they invest in physical assets to enhance productivity, earnings, and overall economic growth. Becker argued that human abilities, knowledge, and health are forms of capital, which he termed “human capital”, and that these attributes are critical drivers of economic success.

This theory of human capital places elements of personnel training and, in particular, education as fundamental determinants of economic performance. With regard to financial literacy, this theory implies that the educational gender gap greatly affects choice and consequently financial literacy levels. Girls in many developing nations attend school and pursue higher education with challenges because of social, cultural, resource dearth, and financial challenges (

Kasozi & Makina, 2021). For instance, a study carried out among participants in Brazil revealed that only 36% of female respondents had a right and accurate answer to basic financial quizzes compared to 48% of male respondents (

Sarpong-Kumankoma et al., 2023). A lack of education is not only across the state, hindering women from being financially literate, it is even preventing them from making decisions regarding savings, investments, and overall management of money.

3.1.3. Behavioral Economics

Psycho-economics is the blend of psychological factors into economic decision-making. This paper uses psycho-economics to explain the low level of financial literacy found in women despite their equal education level to their male counterparts. Research also shows that more women say they lack confidence about their financial literacy compared to men and this can keep them away from seeking information or products related to finance (

OECD, 2020). For instance,

Lunn et al. (

2018) noted that, in answers to questions about financial literacy, women were more likely than men to respond “do not know” owing to low self-confidence and not a lack of knowledge (

N26, 2020). This underlines the lack of programs that offer education but also enhance women’s confidence in the area of finance. Dealing with the psychology aspect in addition to the knowledge deficit, such programs would be much more helpful in engaging women with money.

3.1.4. Structural Inequality Framework

The structural inequality framework addresses a set of patterns that continues to cause gender imbalances in society in all sectors and specifically in the financial domain. Income disparities, employment discrimination, traditional roles of women as being subordinate to men, or lacking the ability to decide on family resources lead to high barriers to credit and education for women (

OECD, 2020). For example, through a survey conducted by

Sarpong-Kumankoma et al. (

2023), it was duly noted that cultural norms still confine women, often restricting their movements and their ability to acquire information vital for improving the literacy levels of women in the use of finances. This framework emphasizes that these disparities should be tackled through policies that are intended to improve women’s economic opportunities for empowerment. Understanding and freeing oneself from these barriers will enable policymakers to work toward improving women’s economic power.

4. Methodology

This research methodology employed a structured and rigorous approach, combining a systematic review and bibliometric analysis to explore the relationship between gender and financial literacy in developing countries. Adhering to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines, the methodology ensured transparency, consistency, and reproducibility throughout the study (

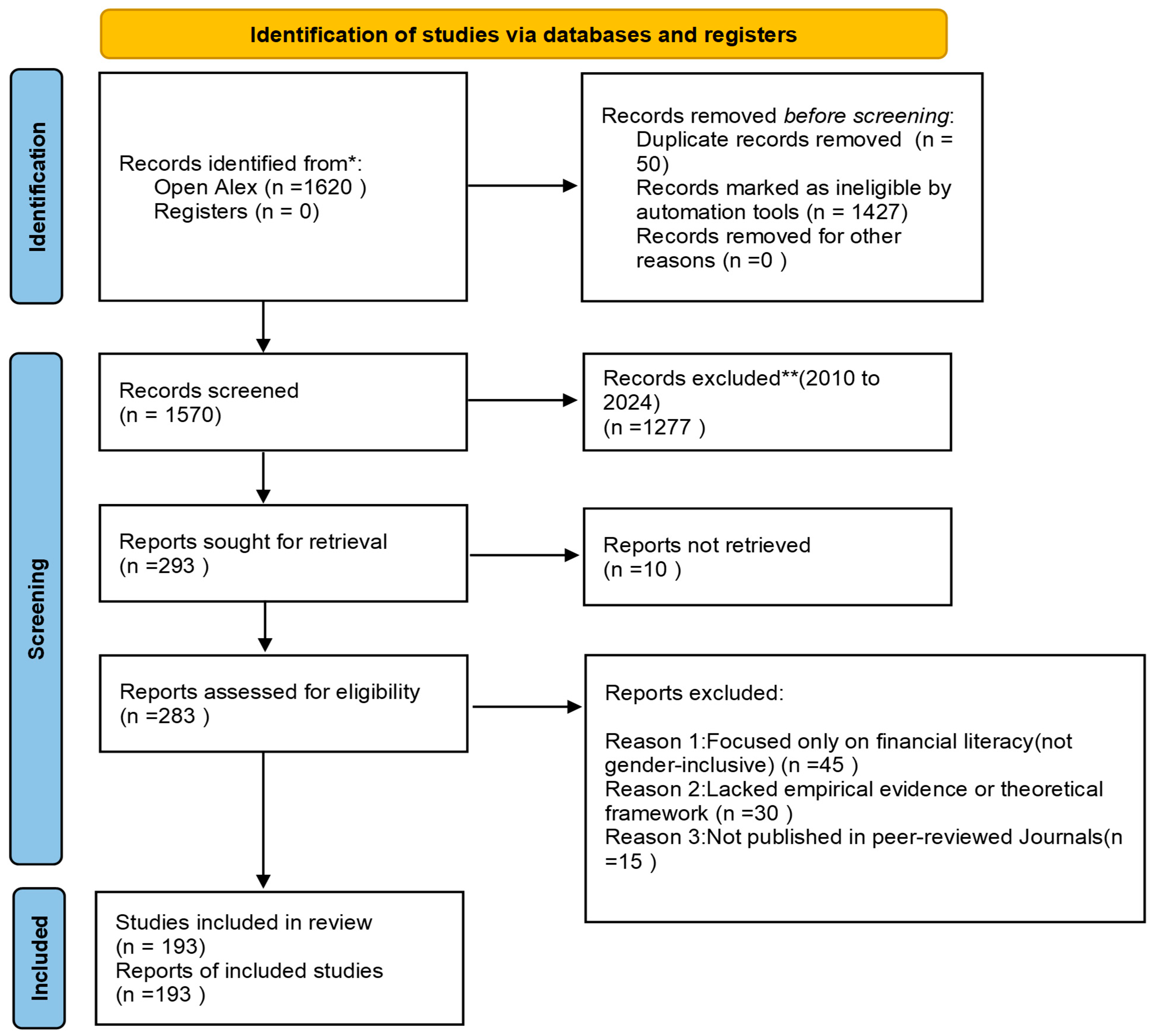

Page et al., 2021). The authors (Maina and Györk) performed a literature search in the Open Alex database. The process was carried out in several well-defined stages, including identification, screening, eligibility assessment, and inclusion of studies as shown in

Figure 1. Each of these stages was systematically executed to select studies most relevant to the research questions, providing a comprehensive understanding of the subject matter. The search was conducted from January 2010 to March 2024, ensuring a comprehensive coverage of recent and relevant studies.

4.1. Search Strategy

The search strategy was carefully designed to identify all relevant studies examining the relationship between gender and financial literacy in developing countries. To ensure a comprehensive yet focused search, a combination of specific keywords and Boolean operators was employed.

The selected keywords included “financial literacy”, “gender”, “developing countries”, “economic empowerment”, “financial inclusion”, “women”, “financial education”, “socio-cultural norms”, and “economic participation”. These terms were chosen to capture various aspects of financial literacy as they relate to gender dynamics, financial access, and broader economic engagement.

To refine the search and retrieve the most relevant literature, Boolean operators were used strategically. Specifically, searches were conducted using the following combinations:

(“financial literacy” AND “gender” AND “developing countries”)—this combination helped identify studies that directly explore financial literacy among men and women within the context of developing economies.

(“financial literacy” AND “women” AND “economic empowerment”)—this search string focused on the literature that examines how financial literacy contributes to women’s economic empowerment, including their ability to make informed financial decisions, access financial resources, and participate in economic activities.

(“financial inclusion” AND “gender” AND “developing countries”)—this search was designed to capture studies that analyze the intersection of gender and financial inclusion, emphasizing challenges faced by women in accessing formal financial services.

By utilizing this search strategy, this study ensured that relevant academic papers, policy reports, and empirical studies addressing gender disparities in financial literacy within developing countries were identified.

4.2. Identification of Records

The first stage involved an exhaustive search across multiple databases, including “Open Alex”, “Scopus”, and “Web of Science” as well as academic repositories and peer-reviewed journals, to identify studies related to gender and financial literacy in developing countries. The search was conducted on August 2024. Specific keywords and search strings were used, such as variations of the terms “gender”, “financial literacy”, and “developing countries” combined with Boolean operators (“AND”, “OR”). Filters were applied to include studies published between 2010 and 2024, in English, and in peer-reviewed journals. This search resulted in the identification of 1620 records, providing an extensive pool of studies to assess.

Following the identification stage, a significant number of records were removed prior to screening. A total of 1427 records were excluded, with the primary reasons being duplicate entries (50 records) and ineligibility flagged by automated tools (1377 records). The automated tools filtered out studies that did not meet basic eligibility criteria, such as relevance to the research topic, language restrictions, or publication type. This step helped narrow down the pool of studies, ensuring that the remaining records were more likely to provide valuable insights into the research questions.

4.3. Screening of Records

During the screening phase, the remaining 1570 records were carefully examined based on their titles, abstracts, and keywords to determine their alignment with the inclusion criteria. The screening was conducted independently by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Studies were assessed to ensure they addressed both gender and financial literacy in the context of developing countries and fit within the scope of the review’s research objectives. A total of 1277 records were excluded at this stage, primarily due to their focus being irrelevant to the topic of interest, being overly general, or falling outside the scope of developing countries. This phase helped to ensure that only the most relevant and focused studies progressed to the next stage of eligibility assessment.

The remaining 293 reports were retrieved in full and subjected to a detailed eligibility assessment. This stage involved a thorough review of the full texts of the studies by two independent reviewers to evaluate whether they met the predefined inclusion criteria. The criteria required that studies:

Focus on both gender and financial literacy within the context of developing countries

Be published in peer-reviewed journals

Provide either empirical data or a well-grounded theoretical framework

Be published between 2010 and 2024

Be available in English.

Of the 293 reports retrieved, 10 could not be accessed due to restrictions or availability issues, leaving 283 reports for further assessment. These reports underwent a comprehensive review to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the final dataset.

4.4. Inclusion of Studies

Following the eligibility assessment, 193 studies were deemed to meet all the inclusion criteria and were included in the final systematic review. These studies provided valuable empirical evidence or theoretical insights into the relationship between gender and financial literacy, with a focus on developing countries. They were published in peer-reviewed journals, ensuring the credibility and quality of the research. These 193 studies formed the core dataset for the systematic review and bibliometric analysis, providing a comprehensive foundation for understanding the state of research in this field.

4.5. Exclusion Reasons

Several reports were excluded during the review process. The primary reasons for exclusion included:

Studies that focused solely on financial literacy without addressing the gendered aspects (45 studies)

Studies that lacked empirical data or a clear theoretical framework (30 studies)

Studies not published in peer-reviewed journals (15 studies)

Studies published outside the specified time frame (2010–2024) or in languages other than English.

These exclusion criteria ensured that only the most rigorous and relevant studies were included in the review.

4.6. Data Analysis and Bibliometric Techniques

The final dataset of 193 studies was subjected to bibliometric analysis, which involved examining patterns in authorship, citation trends, and key themes in the literature. Bibliometric techniques, including citation analysis and co-authorship analysis, were used to identify influential authors, key publications, and the evolution of research on gender and financial literacy over time. This analysis provided a detailed overview of the research landscape, highlighting trends in the field and mapping out the intellectual heritage of the discipline.

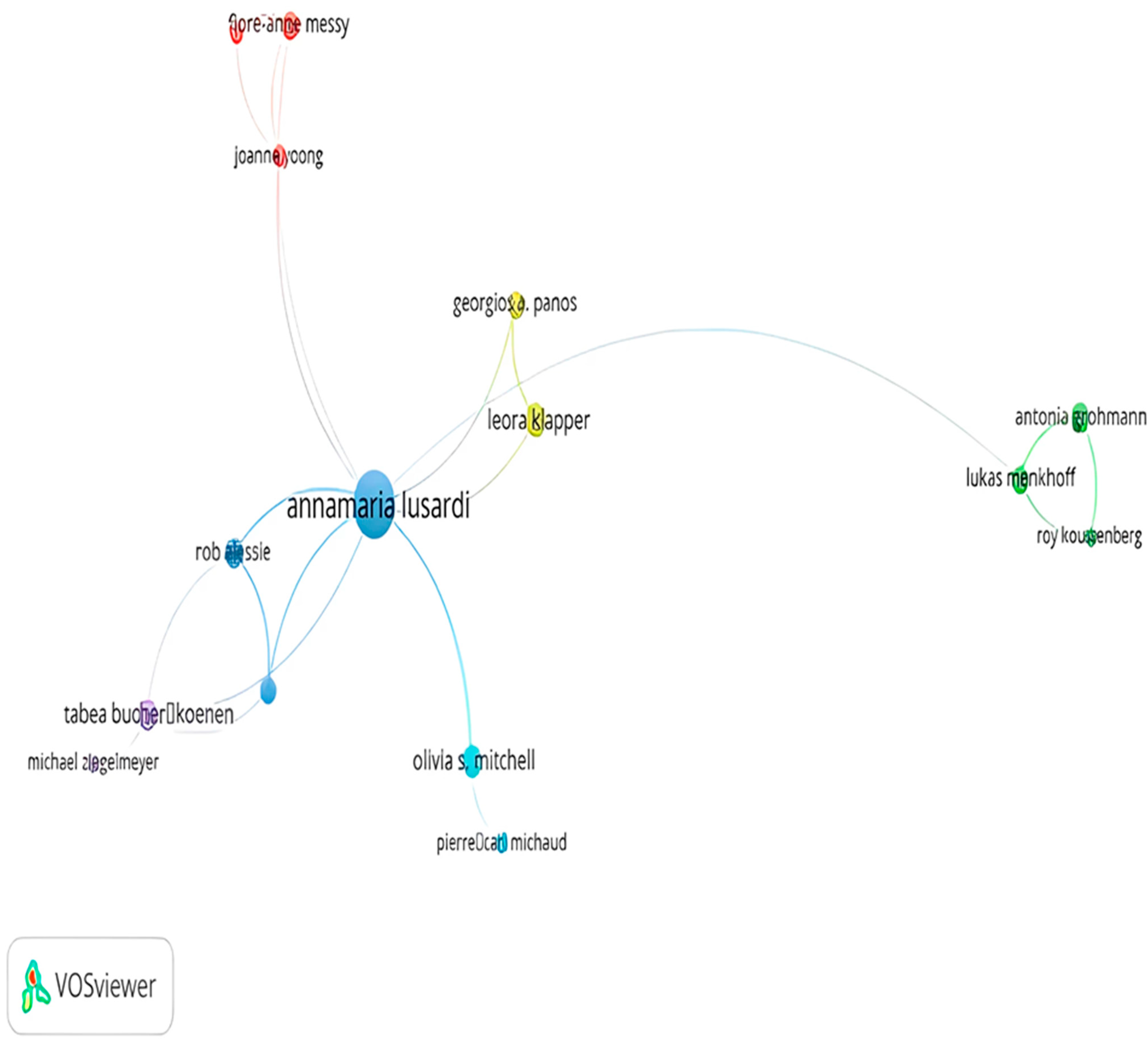

Additionally, co-authorship analysis was performed using VOSviewer 1.6.20, a tool for visualizing collaboration networks. The analysis revealed significant global collaboration in the field, with influential scholars such as Annamaria Lusardi contributing significantly to the discourse. Citation analysis further helped identify leading researchers and publications, contributing to an understanding of the most impactful work in this area.

4.7. Risk of Bias and Quality Assessment

The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool for randomized studies and the ROBINS-I tool for non-randomized studies. Two reviewers independently assessed the risk of bias and discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Studies were categorized as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias based on their methodology, data collection, and reporting.

4.8. Outcomes and Data Collection

The outcomes for which data were sought included:

Gender disparities in financial literacy levels

Factors influencing financial literacy among women in developing countries

Impact of financial literacy interventions on gender equality

Theoretical frameworks used to analyze gender and financial literacy.

Data were extracted for all outcomes reported in the studies, including participant characteristics (e.g., age, socioeconomic status), study design, and funding sources. Missing data or summary statistics were handled by contacting authors for additional information or excluding studies with incomplete data.

4.9. Sensitivity and Reporting Bias

Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess the robustness of the findings by excluding studies with a high risk of bias.

4.10. Limitations

The study relied on published research, potentially excluding unpublished studies or those not meeting publication standards, which may have led to selection bias. Additionally, the study focused on research published between 2010 and 2024, which may have omitted key studies published before this period. Variability in study design, data collection methods, and analysis approaches across studies further complicated comparisons and could affect the validity of conclusions. Despite these limitations, the study provides a comprehensive and insightful overview of the current state of research on gender and financial literacy in developing countries, with recommendations for future research directions in this important field.

4.11. Search Strategy and PRISMA Compliance

The full search strategy, including specific keywords, filters, and limits, is provided. The study adhered to the PRISMA guidelines and the PRISMA flowchart detailing the identification, screening, eligibility, and inclusion process is included as

Figure 1. Two reviewers independently screened records, assessed eligibility, and extracted data, with discrepancies resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. Automation tools, such as EndNote and Covidence, were used to manage references and streamline the screening process.

5. Result

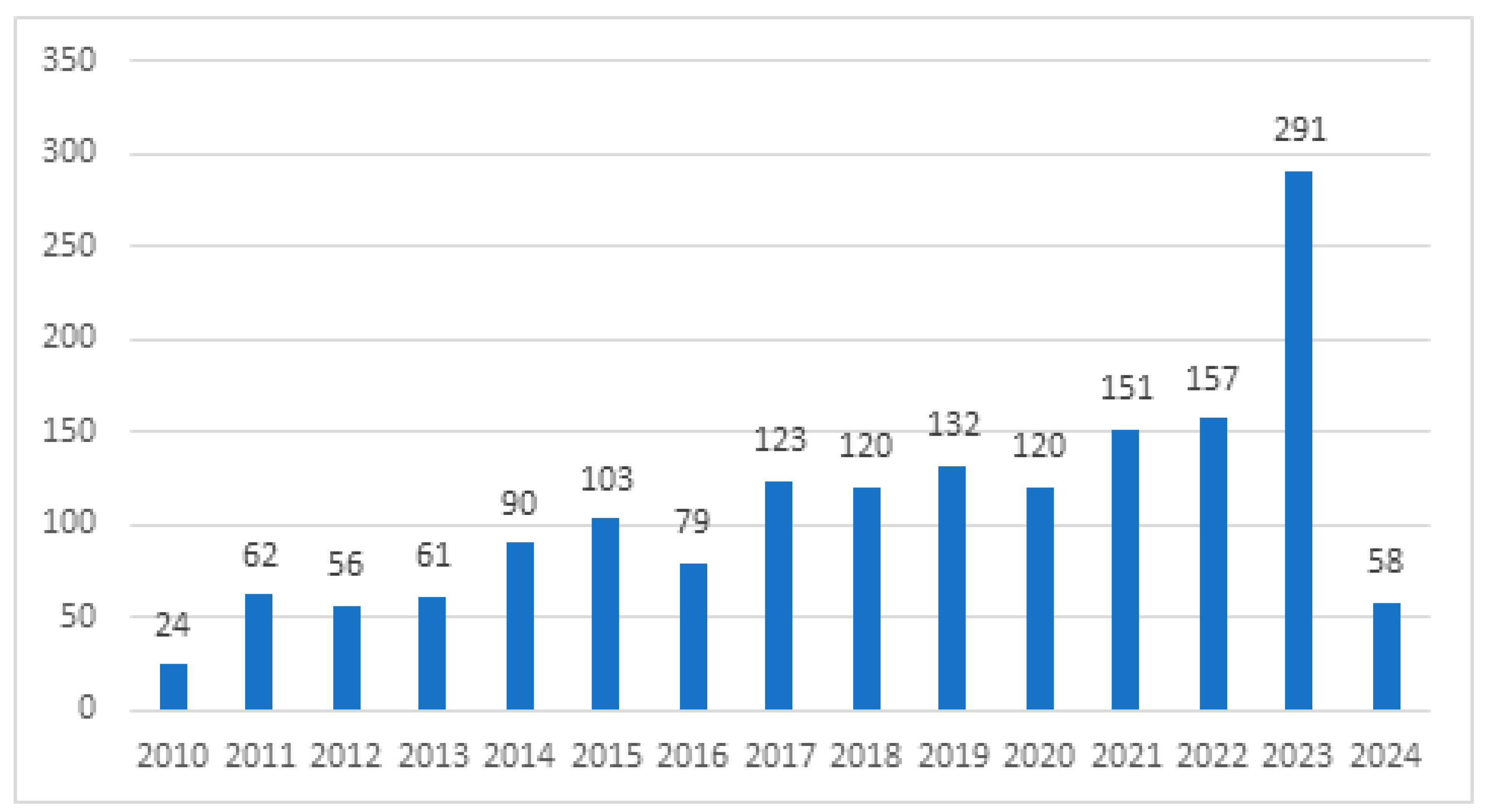

Data for this bibliometric analysis were sourced from Open Alex, an open-source and comprehensive index of the scholarly literature. The initial search yielded a total of 1620 journals related to financial literacy and gender as shown in

Figure 2.

In order to ensure relevance, these journals were screened for direct relationships between financial literacy, and gender issues. Following the application of these screening criteria, 193 journals were identified as having a significant focus on the intersection of financial literacy and gender in developing countries. To refine the selection of relevant journals, specific inclusion and exclusion criteria were established and applied as shown in

Table 1.

Once the selection of journals was finalized, several steps were undertaken to analyze the data as shown in

Table 2.

To enhance the interpretation of the bibliometric data, the study used VOSviewer software to visualize the results. This software allowed the creation of visual representations, including keyword co-occurrence maps, authorship networks, and citation patterns. These visual tools helped identify relationships between key concepts, researchers, and institutions in the field of financial literacy and gender as shown in

Table 3.

5.1. Co-Authorship

The co-authorship network presented in

Figure 3 provides valuable insights into the collaborative relationships and research communities within the field of financial literacy and gender. A prominent figure, Annamaria Lusardi, emerges as the central node, reflecting her extensive collaborations and significant influence. Her network includes key collaborators such as Leora Klapper, Rob Alessie, and Lukas Menkhoff, forming strong research communities.

The map also highlights the international nature of research in this field, with connections between authors from different countries. This suggests a growing global exchange of ideas and collaborations. Additionally, the presence of newer authors, such as Olivia S. Mitchell and Pierre-Carl Michaud, indicates the emergence of new research communities and collaborations.

Overall, the co-authorship network reveals the collaborative nature of research in financial literacy and gender. It highlights the central role of Annamaria Lusardi and Leora Klapper in shaping the field, while also demonstrating the growing internationalization of research and the emergence of new research communities.

5.2. Co-Occurrence Analysis

The co-occurrence network presented in

Figure 4 provides valuable insights into the key concepts and relationships within the field of financial literacy and gender. The central node, financial literacy, reflects its significance as a core concept. Its strong connections to economics, education, and psychology highlight the interdisciplinary nature of the field.

The network also reveals emerging trends, such as the growing interest in behavioral economics and financial inclusion. These concepts, while less prominent in the literature, suggest the evolving nature of research in this area.

Overall, the co-occurrence network demonstrates the complex interplay between financial literacy and various disciplines. By understanding the key concepts and their relationships, researchers can identify gaps in the literature and inform future research directions.

5.3. Overlay Visualization

The VOSviewer map, as presented in

Figure 5, offers an insightful overlay visualization of the co-occurrence network of keywords associated with financial literacy and gender research. This map reveals various clusters of terms, with each cluster depicted in distinct colors to represent different thematic groupings and semantic relationships.

One of the central clusters is focused on financial literacy and economics, where the term “financial literacy” is at the core, surrounded by other related economic terms such as “finance”, “monetary economics”, and “debt”. These terms are typically shown in shades of green, symbolizing their strong association with financial literacy. This cluster highlights the economic dimension of the research, underscoring the link between financial knowledge and broader economic concepts.

Another significant cluster emphasizes education and psychology. This group includes terms related to educational practices, such as “literacy” and “pedagogy” alongside psychological terms like “cognition” and “personality”. The blue coloring of this cluster points to the intersection of education and human psychology, reflecting how cognitive factors and educational interventions influence financial literacy.

A third thematic cluster centers around law and regulation, featuring terms like “equity (law)” and “regulation”. These terms are predominantly represented in yellow, suggesting a focus on the legal and regulatory framework that governs financial practices and literacy.

Additionally, there is a social and demographic factors cluster, which includes terms such as “gender”, “age”, and “income”. The red hue associated with this cluster highlights the role of social and demographic variables in shaping financial literacy outcomes, particularly how these factors intersect with gender.

In terms of relationships and overlaps, the VOSviewer map reveals that the clusters are not strictly isolated from each other. There are overlaps, especially between clusters related to education and psychology, which suggests a close relationship between these factors in shaping financial behavior and literacy. The map also shows hierarchical relationships between terms, with some representing broader concepts (e.g., “economics”) and others more specific topics (e.g., “monetary policy”).

The overall insights from the overlay visualization provide a comprehensive understanding of how various economic, educational, psychological, and social factors converge to influence financial literacy. The hierarchical structure also indicates a layered knowledge base, where more general concepts serve as the foundation for more specific research topics.

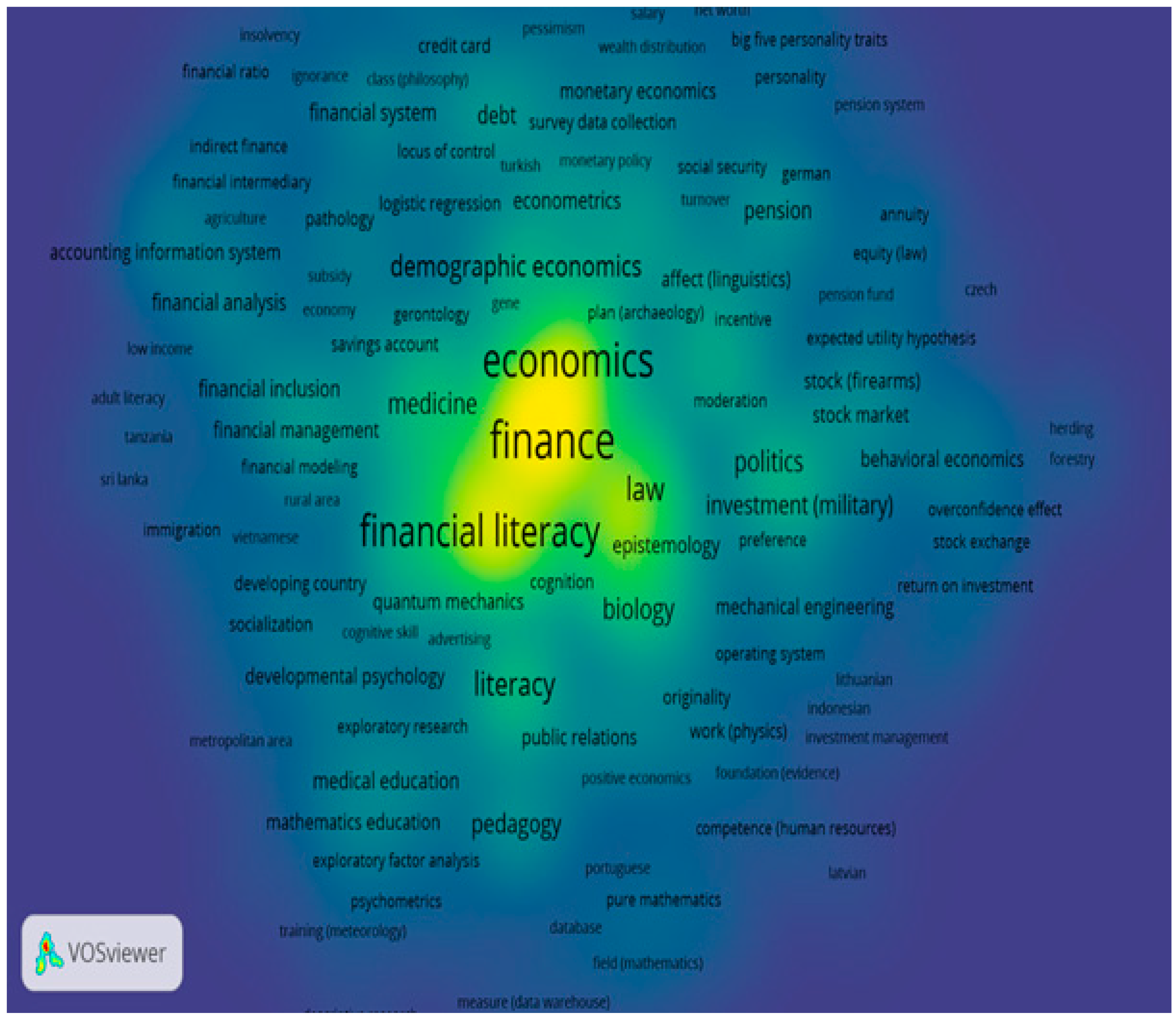

5.4. Density Visualization Co-Accurance

Figure 6 showcases a VOSviewer map that provides a density visualization of the co-occurrence network, offering a detailed perspective on the relationships among frequently co-occurring terms in the realm of financial literacy and gender. The map uses varying color intensities to denote the density of connections between terms, with darker colors indicating a higher concentration of co-occurrence.

Central clusters: The map identifies several key clusters that are densely interconnected. Notably, the financial literacy and economics cluster stands out, featuring terms like “financial literacy”, “economics”, “finance”, and “debt”. This cluster illustrates the significant interplay among these concepts, underscoring how financial literacy is closely linked with economic and financial issues. Another prominent cluster is education and psychology, which includes terms such as “literacy”, “education”, “psychology”, and “cognition”. This cluster highlights the essential role that educational and psychological factors play in influencing financial behaviors and outcomes.

Peripheral clusters: On the map’s periphery, less densely connected clusters are evident. The law and regulation cluster includes terms related to legal and regulatory aspects, such as “law”, “equity (law)”, and “regulation”. This cluster reflects how legal frameworks and regulatory measures impact financial practices. Another peripheral cluster, social and demographic factors, encompasses terms like “gender”, “age”, and “income”. This cluster reveals the intersection of social and demographic variables with financial literacy and behavior.

Overlapping clusters: The visualization indicates that clusters are not entirely separate. There are noticeable overlaps between terms from different clusters. For instance, terms from the education and psychology cluster frequently intersect with those from the financial literacy and economics cluster, suggesting a strong link between educational interventions, psychological factors, and financial behavior.

Hierarchical relationships: The map also displays a hierarchical structure within the knowledge base. Some terms appear as more general concepts, such as “economics”, while others are more specific, like “monetary policy”. This hierarchical organization reflects the broader and more specific categories within the field, offering insights into how specific terms relate to general concepts.

The density visualization effectively captures the central themes and connections within the domain of financial literacy and gender. It emphasizes the crucial role of financial literacy and economic factors while also highlighting the importance of educational and psychological influences. Additionally, the map illustrates the hierarchical nature of the knowledge base and the interconnectedness of different clusters of terms.

5.5. Citation

Table 4 summarizes key authors and their influential works within the field of financial literacy and gender. It provides an overview of their contributions based on citation frequency and relevance:

This table introduces prominent figures in the field of financial literacy and gender, highlighting their most cited works. The list includes

Van Rooij et al. (

2011), known for his influential study on financial literacy and retirement planning;

Grinblatt et al. (

2011) whose work, although not specifically titled, is widely referenced;

Klapper et al. (

2012), whose research on global financial literacy trends is highly regarded;

Grohmann (

2018), recognized for her comprehensive review of financial literacy and inclusion; and

Blake (

2022) who provides a recent review of the literature on retirement planning and financial literacy. Each entry underscores the significance of these works in advancing the understanding of financial literacy and its intersections with gender.

7. Conclusions

This systematic review and bibliometric study of gender gaps in financial literacy in developing nations has highlighted critical disparities, underlying causes, and the need for targeted interventions. Across multiple studies, women consistently demonstrate lower levels of financial literacy compared to men, primarily due to socio-cultural norms, educational barriers, and financial exclusion. These disparities limit women’s financial decision-making abilities and economic participation, reinforcing systemic inequalities.

The findings emphasize the urgent need for gender-sensitive financial education programs that address cultural and structural barriers. Policymakers should implement strategies that promote equal access to financial knowledge, enhance women’s confidence in financial decision-making, and improve the availability of financial services tailored to women’s needs. Moreover, financial institutions and governments must work together to create inclusive policies that bridge the gender gap in financial literacy.

While the study provides valuable insights applicable across various developing regions, it also acknowledges the contextual differences that influence financial literacy levels. Factors such as educational access, economic structures, and cultural norms vary significantly across regions like sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Latin America. Future research should explore region-specific challenges and best practices to ensure that interventions are both effective and sustainable.

Ultimately, improving financial literacy among women is not only a pathway to individual empowerment but also a crucial driver of economic growth and stability in developing nations. Addressing these gaps will enhance household financial management, increase women’s economic contributions, and foster more equitable and resilient economies. This study lays a strong foundation for future research and policy efforts aimed at achieving financial literacy equity and economic inclusion for all.