The Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Performance on Shareholder Wealth: The Role of Advisory Services

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review and Hypothesis Development

3. Data and Methodology

3.1. Sample Selection

3.2. Data Sources

3.3. Empirical Methods

4. Empirical Results

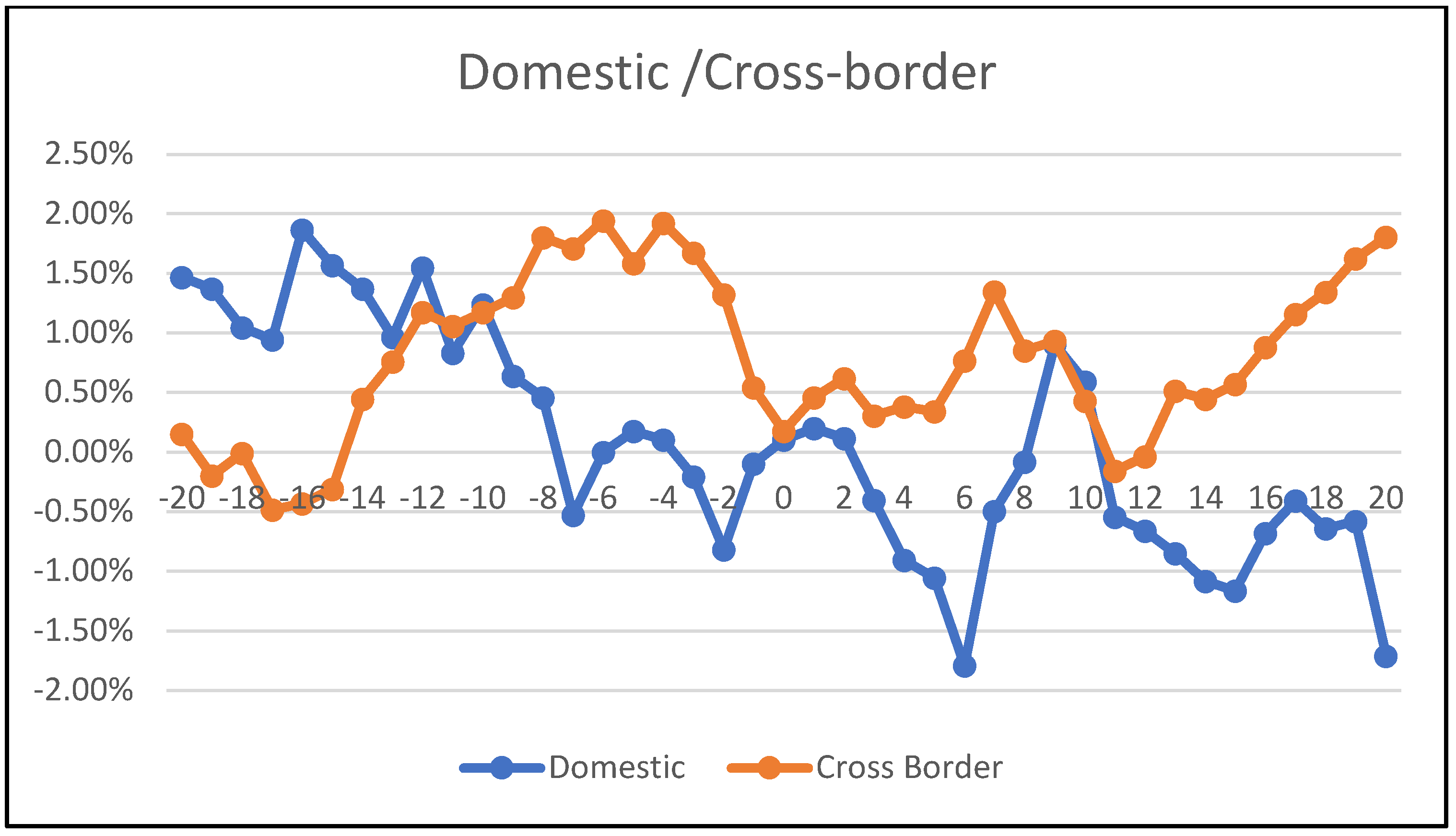

4.1. Wealth Effects of Domestic and Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions

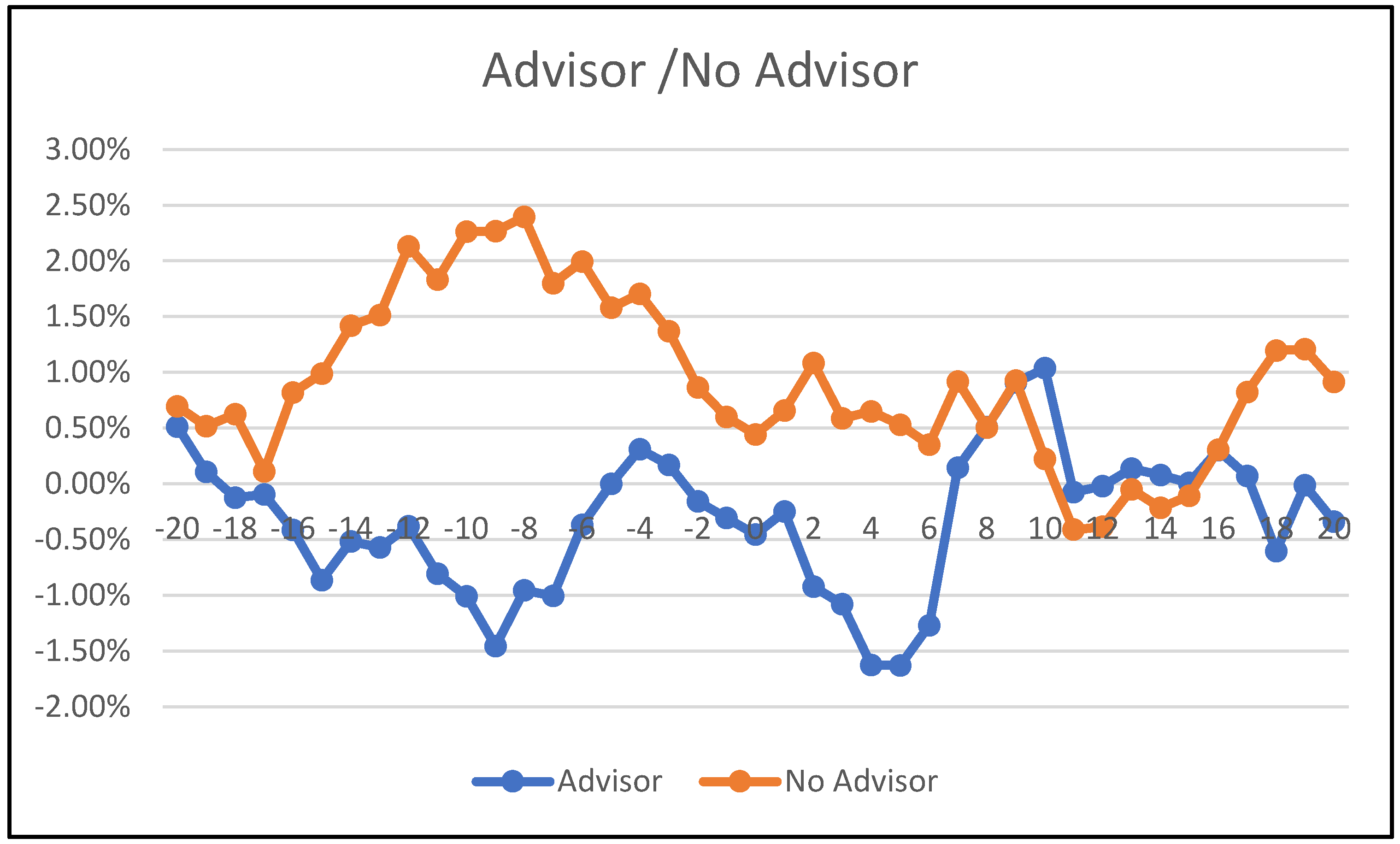

4.2. Influence of Advisor Services on Wealth Effects Through Mergers and Acquisitions

5. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Aleksanyan, M., Hao, Z., Vagenas-Nanos, E., & Verwijmeren, P. (2020). Do state visits affect cross-border mergers and acquisitions? Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aw, M. S. B., & Chatterjee, R. A. (2004). The performance of UK firms acquiring large cross-border and domestic takeover targets. Applied Financial Economics, 14(5), 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aybar, B., & Ficici, A. (2009). Cross-border acquisitions and firm value: An analysis of emerging-market multinationals. Journal of International Business Studies, 40(8), 1317–1338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, Y., & Li, J. (2023). Cross-border M&A, gender-equal culture, and board gender diversity. Journal of Corporate Finance, 84, 102527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, D., Mitra, S., & Purohit, A. (2023). Does effective democracy explain MNE location choice?: Attractiveness to FDI and cross-border M&As. Journal of Business Research, 167, 114188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boubakri, N., Cosset, J., Mishra, D., & Somé, H. Y. (2023). The value of risk-taking in mergers: Role of ownership and country legal institutions. Journal of Empirical Finance, 70, 427–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, M., Desai, A., & Han Kim, E. (1988). Synergistic gains from corporate acquisitions and their division between the stockholders of target and acquiring firms. Journal of financial Economics, 21(1), 3–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campa, J. M., & Hernando, I. (2004). Shareholder value creation in European M&As. European financial management, 10(1), 47–81. [Google Scholar]

- Chandrika, R., Mahesh, R., & Tripathy, N. (2022). Is India a pollution haven? Evidence from cross-border mergers and acquisitions. Journal of Cleaner Production, 376, 134355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaudhry, A. N., Kontonikas, A., & Vagenas-Nanos, E. (2021). Social networks and the informational role of financial advisory firms centrality in mergers and acquisitions. British Journal of Management, 33(2), 958–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X., Liang, X., & Wu, H. (2022). Cross-border mergers and acquisitions and CSR performance: Evidence from China. Journal of Business Ethics, 183(1), 255–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, C., Yang, X., Jiang, F., & Yang, Z. (2023). How to synergize different institutional logics of firms in Cross-border Acquisitions: A Matching Theory Perspective. Management International Review, 63(3), 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clampit, J., Gaffney, N., Fabian, F., & Stafford, T. (2023). Institutional misalignment and escape-based FDI: A prospect theory lens. International Business Review, 32(3), 102099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conn, R. L., Cosh, A., Guest, P. M., & Hughes, A. (2005). The impact on UK acquirers of domestic, cross-border, public and private acquisitions. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 32(5–6), 815–870. [Google Scholar]

- Danbolt, J., & Maciver, G. (2012). Cross-border versus domestic acquisitions and the impact on shareholder wealth. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 39(7–8), 1028–1067. [Google Scholar]

- Dutta, S., Saadi, S., & Zhu, P. (2013). Does payment method matter in cross-border acquisitions. International Review of Economics & Finance, 25, 91–107. [Google Scholar]

- Eckbo, B. E., & Thorburn, K. S. (2000). Gains to bidder firms revisited: Domestic and foreign acquisitions in Canada. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 35(1), 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Liu, C., & Yawson, A. (2023). Economic shocks, M&A advisors, and industry takeover activity. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 82, 102156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fieberg, C., Lopatta, K., Tammen, T., & Tideman, S. A. (2021). Political affinity and investors’ response to the acquisition premium in cross-border M&A transactions—A moderation analysis. Strategic Management Journal, 42(13), 2477–2492. [Google Scholar]

- Goergen, M., & Renneboog, L. (2004). Shareholder wealth effects of European domestic and cross-border takeover bids. European Financial Management, 10, 9–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregory, A., & O’Donohoe, S. (2014). Do cross border and domestic acquisitions differ? Evidence from the acquisition of UK targets. International Review of Financial Analysis, 31, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inoue, K., & Ings, R. (2012, April 30). Do cross-border acquisitions create more shareholder value than domestic deals for firms in a mature economy? The Japanese case. In The Japanese Case (January 1, 2012). Midwest Finance Association 2012 Annual Meetings Paper. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2048571 (accessed on 12 December 2024).

- Kaplan, S. N., & Weisbach, M. S. (1992). The success of acquisitions: Evidence from divestitures. The Journal of Finance, 47(1), 107–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashiramka, S., & Rao, N. V. (2014). Shareholders’ wealth effects of mergers and acquisitions on acquiring firms in the Indian IT and ITeS sector. South Asian Journal of Managemen, 21(3), 140. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Li, Y., Yang, R., & Li, X. (2019). How do chinese firms perform before and after cross-border mergers and acquisitions? Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 57(2), 348–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lowinski, F., Schiereck, D., & Thomas, T. W. (2004). The effect of cross-border acquisitions on shareholder wealth—evidence from Switzerland. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 22(4), 315–330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martynova, M., & Renneboog, L. (2011). The performance of the European market for corporate control: Evidence from the fifth takeover wave. European Financial Management, 17(2), 208–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, K. J., & Noseleit, F. (2021). Too many cooks spoil the broth: On the impact of external advisors on mergers and acquisitions. Review of Managerial Science, 16(6), 1817–1852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A., & Goel, R. (2005). Return to shareholders from mergers: The case of RIL and RPL merger. IIMB Management Review, 17(3), 69–79. [Google Scholar]

- Rani, N., Yadav, S. S., & Jain, P. K. (2013). Market response to the announcement of mergers and acquisitions: An empirical study from India. Vision. The Journal of Business Perspective, 17(1), 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rani, N., Yadav, S. S., & Jain, P. K. (2014). Impact of domestic and cross-border acquisitions on acquirer shareholders’ wealth: Empirical evidence from Indian corporate. International Journal of Business and Management, 9(3), 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A., & Raat, E. (2014). Acquiring control in emerging markets: Foreign acquisitions in Eastern Europe and the effect on shareholder wealth. Research in International Business and Finance, 37, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Smith, R. L., & Kim, J. H. (1994). The combined effects of free cash flow and financial slack on bidder and target stock returns. Journal of Business, 67, 281–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sudarsanam, S., & Mahate, A. A. (2003). Glamour acquirers, method of payment and post-acquisition performance: The UK evidence. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 30(1–2), 299–342. [Google Scholar]

- Tao, F., Liu, X., Gao, L., & Xia, E. (2017). Do cross-border mergers and acquisitions increase short-term market performance? The case of Chinese firms. International Business Review, 26(1), 189–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Travlos, N. G. (1987). Corporate takeover bids, methods of payment, and bidding firms’ stock returns. The Journal of Finance, 42(4), 943–963. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, M., & Boateng, A. (2009). An analysis of short-run performance of cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from the UK acquiring firms. Review of Accounting and Finance, 8(4), 431–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C., Jiang, H., & Chen, C. (2023). Differences in returns to cross-border and domestic mergers and acquisitions: Empirical evidence from China using PSM-DID. Finance Research Letters, 55, 103961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuce, A., & Ng, A. (2005). Effects of private and public Canadian mergers. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences/Revue Canadienne des Sciences de l’Administration, 22(2), 111–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z., Lyles, M. A., & Wu, C. (2020). The stock market performance of exploration-oriented and exploitation-oriented cross-border mergers and acquisitions: Evidence from emerging market enterprises. International Business Review, 29(4), 101707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Authors | Sample Periods | Sample Size | Market | Methodology | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eckbo and Thorburn (2000) | 1964–1982 | 1846 | Canada | Event Study | Domestic acquirers earn significantly higher wealth gains than cross-border acquirers. |

| Goergen and Renneboog (2004) | 1993–2000 | 187 | Europe | Event Study Methods and OLS Regression | Acquirers experience a positive abnormal return in a cross-border transaction; however, cross-border merger acquirers earn more as compared to domestic mergers. |

| Campa and Hernando (2004) | 1998–2000 | 262 | Europe | Event Study and OLS Regression | Acquirers’ return on average is zero, and there is a significant positive return to the target shareholder of cross-border mergers, with acquirers earning less as compared to domestic mergers. |

| Aw and Chatterjee (2004) | 1991–1996 | 79 | UK | Event Study | Negative return to both the acquirer and target shareholder. The UK acquirer is superior in domestic acquisitions as compared to foreign acquisitions. |

| Conn et al. (2005) | 1984–1998 | 4000 | UK | Event Study, BHAR, and OLS Regression | Negative return to the acquirer firms in a cross-border transaction. Cross-border acquisitions earn less wealth gains than domestic acquisitions. |

| Aybar and Ficici (2009) | 1991–2004 | 433 | 58 EM | Event Study and OLS Regression | Negative abnormal return for the acquirer. |

| Uddin and Boateng (2009) | 1994–2003 | 373 | UK | Event Study | The acquiring firms find a significantly negative abnormal return. |

| Martynova and Renneboog (2011) | 1993–2001 | 2419 | Europe and the UK | Event Study and OLS Regression | There are substantial share price increases at the announcement, most of which are captured by the target firm’s shareholders. |

| Danbolt and Maciver (2012) | 1980–2008 | 251 | UK | Event Study and OLS Regression | Both the acquirer and the target firms gain more as compared to domestic acquisitions. |

| Inoue and Ings (2012) | 2000–2010 | 198 | Japan | Event Study | The shareholder of cross-border deals receives a more positive return as compared to a domestic one. |

| Dutta et al. (2013) | 1993–2002 | 1300 | Canada | Event Study, BHAR, and OLS Regression | Cross-border deals generate more return than domestic deals; however, stock finances show the positive and significant impact. |

| Gregory and O’Donohoe (2014) | 1990–2005 | 119 | UK | Event Study and OLS Regression | Cross-border performance is better as compared to domestic performance; however, the acquiring firm incurs losses in cross-border mergers. |

| Sharma and Raat (2014) | 2000–2011 | 125 | DM | Event Study and OLS Regression | The developed market acquiring firm has a significant positive cumulative abnormal return in the three-day event window. |

| Tao et al. (2017) | 2000–2012 | 165 | China | Event Study | The stock market responded favorably and strongly, on average, according to Chinese listed corporations. |

| Liu et al. (2019) | 2007–2012 | 86 | China | DID Methods | The findings showed that domestic M&As outperformed cross-border M&As in terms of improving the firms’ financial performances. |

| Zhang et al. (2020) | 2000–2015 | 477 | China | Event Study and Regression | Our analysis of cross-border M&A’s data reveals that acquisitions focused on exploration perform worse on the stock market than those focused on exploitation. |

| Yuan et al. (2023) | 2010–2019 | 1616 | China | PSM_DID Methods | The outcome proved that domestic M&As can generate a higher market value than international M&As. |

| Event Window | Positive:Negative | CAAR | t-Statistics | Prob. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [−20, 20] | 29:29 | 0.018 | 0.586 | 0.557 |

| [−10, 10] | 26:32 | −0.006 | −0.318 | 0.750 |

| [−5, 5] | 22:36 | −0.016 | −1.213 | 0.224 |

| [−1, 1] | 17:41 | −0.008 | −1.260 | 0.207 |

| [0] | 22:36 | −0.003 | −1.089 | 0.276 |

| [−1, 0] | 19:39 | −0.011 | −1.846 | 0.064 ** |

| [−5, −1] | 23:35 | −0.014 | −1.416 | 0.156 |

| [−10, −1] | 24:34 | −0.005 | −0.417 | 0.676 |

| [−20, −1] | 30:28 | 0.005 | 0.304 | 0.761 |

| [1, 5] | 33:25 | 0.001 | 0.184 | 0.853 |

| [1, 10] | 36:22 | 0.002 | 0.240 | 0.809 |

| [1, 20] | 32:26 | 0.016 | 0.895 | 0.370 |

| Event Window | Domestic Mergers and Acquisitions | Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions | Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAR | t-Statistics | Prob. | CAAR | t-Statistics | Prob. | t-Statistics | Prob. | ||

| [−20, 20] | −0.017 | −0.433 | 0.665 | 0.018 | 0.586 | 0.558 | 0.035 | −0.699 | 0.487 |

| [−10, 10] | −0.002 | −0.099 | 0.921 | −0.006 | −0.318 | 0.750 | −0.004 | 0.121 | 0.904 |

| [−5, 5] | −0.011 | −0.661 | 0.508 | −0.016 | −1.214 | 0.225 | −0.006 | 0.260 | 0.795 |

| [−1, 1] | 0.010 | 0.988 | 0.323 | −0.009 | −1.261 | 0.208 | −0.019 | 1.578 | 0.118 |

| [0] | 0.002 | 0.448 | 0.654 | −0.004 | −1.089 | 0.276 | −0.006 | 1.017 | 0.312 |

| [−1, 0] | 0.009 | 1.389 | 0.165 | −0.012 | −1.847 | 0.064 ** | −0.021 | 2.160 | 0.334 * |

| [−5, −1] | −0.001 | −0.113 | 0.910 | −0.014 | −1.417 | 0.157 | −0.013 | 0.906 | 0.368 |

| [−10, −1] | −0.009 | −0.544 | 0.587 | −0.005 | −0.417 | 0.676 | 0.004 | −0.200 | 0.842 |

| [−20, −1] | −0.001 | −0.044 | 0.965 | 0.005 | 0.304 | 0.761 | 0.006 | −0.223 | 0.824 |

| [1, 5] | −0.012 | −1.043 | 0.297 | 0.002 | 0.184 | 0.854 | 0.013 | −0.909 | 0.366 |

| [1, 10] | 0.005 | 0.302 | 0.763 | 0.003 | 0.241 | 0.810 | −0.002 | 0.123 | 0.902 |

| [1, 20] | −0.018 | −0.634 | 0.526 | 0.016 | 0.895 | 0.371 | 0.035 | −1.066 | 0.289 |

| Event Window | M&A’s with Advisor Service | M&A’s Without Advisor Service | Effect of Advisor Service | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAAR | t-Statistics | Prob. | CAAR | t-Statistics | Prob. | t-Statistics | Prob. | ||

| [−20, 20] | −0.003 | −0.134 | 0.894 | 0.009 | 0.269 | 0.788 | −0.013 | −0.241 | 0.810 |

| [−10, 10] | 0.018 | 1.057 | 0.291 | −0.016 | −0.769 | 0.442 | 0.035 | 1.063 | 0.291 |

| [−5, 5] | −0.013 | −1.364 | 0.173 | −0.015 | −1.016 | 0.310 | 0.002 | 0.093 | 0.926 |

| [−1, 1] | −0.001 | −0.135 | 0.893 | −0.002 | −0.257 | 0.798 | 0.001 | 0.089 | 0.930 |

| [0] | −0.002 | −0.419 | 0.675 | −0.002 | −0.442 | 0.659 | 0.000 | 0.016 | 0.987 |

| [−1, 0] | −0.003 | −0.484 | 0.629 | −0.004 | −0.665 | 0.506 | 0.001 | 0.122 | 0.903 |

| [−5, −1] | 0.001 | 0.083 | 0.934 | −0.014 | −1.443 | 0.149 | 0.015 | 0.979 | 0.330 |

| [−10, −1] | 0.005 | 0.519 | 0.604 | −0.012 | −0.880 | 0.379 | 0.017 | 0.815 | 0.417 |

| [−20, −1] | −0.003 | −0.194 | 0.846 | 0.006 | 0.316 | 0.752 | −0.009 | −0.307 | 0.760 |

| [1, 5] | −0.012 | −1.265 | 0.206 | 0.001 | 0.094 | 0.925 | −0.013 | −0.840 | 0.403 |

| [1, 10] | 0.015 | 1.018 | 0.309 | −0.002 | −0.193 | 0.847 | 0.017 | 0.897 | 0.372 |

| [1, 20] | 0.001 | 0.059 | 0.953 | 0.005 | 0.222 | 0.824 | −0.004 | −0.106 | 0.916 |

| Variables | N | Mean | Median | Std. Deviation | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cross-Border Target | 92 | 0.630 | 1.000 | 0.485 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Advice of Investment bank | 92 | 0.326 | 0.000 | 0.471 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Method of Payment | 92 | 0.446 | 0.000 | 0.500 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| log size (Market Capitalization) | 92 | 9.884 | 9.865 | 2.153 | 4.723 | 14.864 |

| Price-to-book value ratio | 92 | 0.883 | 0.862 | 0.850 | −1.926 | 3.426 |

| CAAR, [−10, −1] | 92 | −0.007 | −0.011 | 0.095 | −0.298 | 0.329 |

| Variable | Coefficient |

|---|---|

| Constant | −0.014 |

| Cross-border deals | −0.011 |

| Advisor Services | 0.025 |

| Method of Payment | 0.039 ** |

| Log size (Market Capitalization) | −0.008 |

| Price-book-value ratio | 0.080 * |

| N | 92 |

| R Squared | 0.125 |

| Adjusted R-squared | 0.074 |

| Durbin–Watson statistic | 2.029 |

| F-Value | 2.464 |

| Probability (F-stat) | 0.039 * |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Satapathy, D.P.; Soni, T.K.; Patjoshi, P.K.; Jamwal, D.S. The Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Performance on Shareholder Wealth: The Role of Advisory Services. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020107

Satapathy DP, Soni TK, Patjoshi PK, Jamwal DS. The Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Performance on Shareholder Wealth: The Role of Advisory Services. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(2):107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020107

Chicago/Turabian StyleSatapathy, Debi Prasad, Tarun Kumar Soni, Pramod Kumar Patjoshi, and Divya Singh Jamwal. 2025. "The Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Performance on Shareholder Wealth: The Role of Advisory Services" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 2: 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020107

APA StyleSatapathy, D. P., Soni, T. K., Patjoshi, P. K., & Jamwal, D. S. (2025). The Effect of Cross-Border Mergers and Acquisitions Performance on Shareholder Wealth: The Role of Advisory Services. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18020107