Stock Market Returns and Crude Oil Price Volatility: A Comparative Study Between Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing Countries

Abstract

1. Introduction

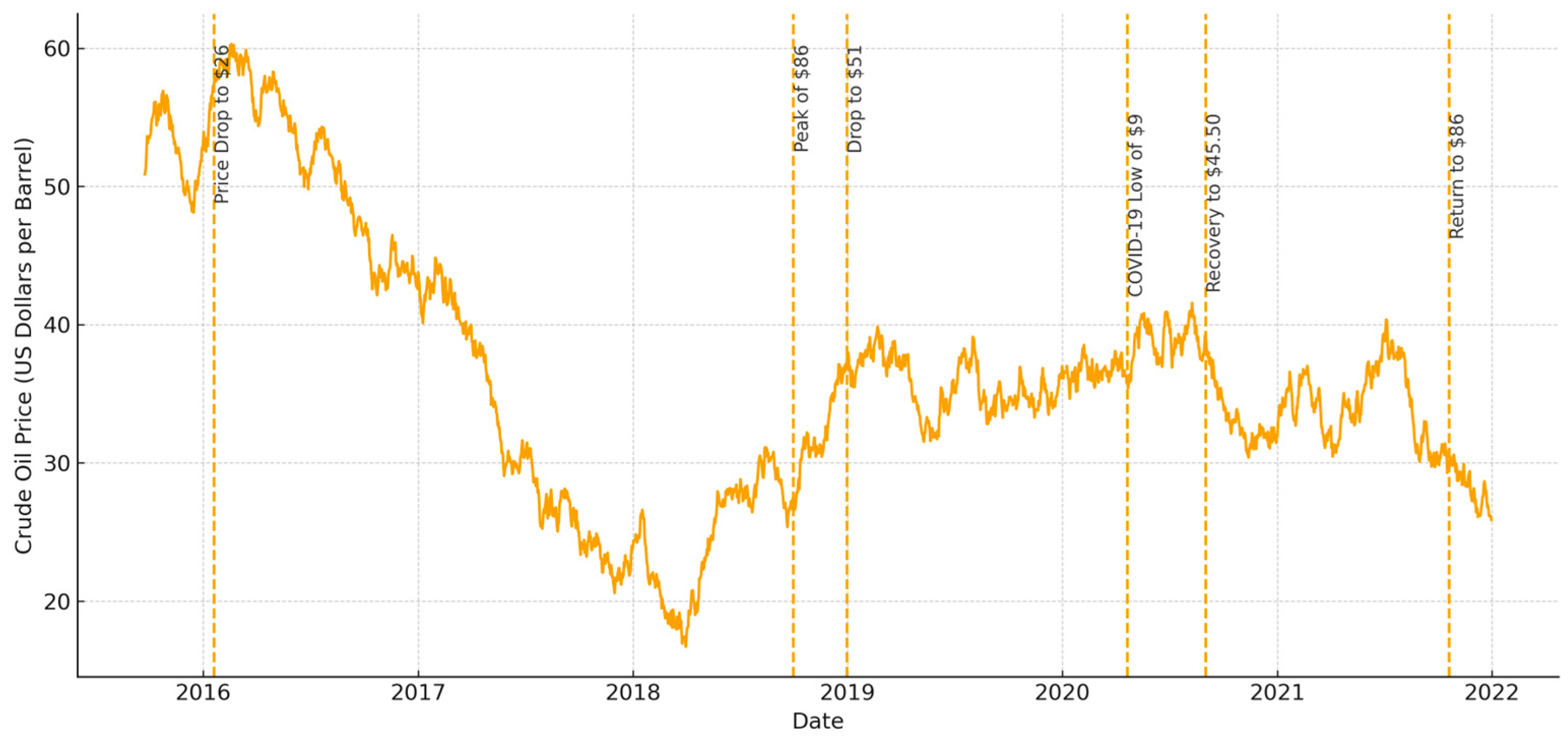

2. Data

3. Methodology

4. Results and Interpretation

4.1. Impacts of Oil Prices Pre-COVID-19

4.2. Impacts of Oil Prices Intra COVID-19

5. Robustness Checks and Summary of Results

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsalman, Z., & Herrera, A. M. (2015). Oil price shocks and the U.S. stock market: Do sign and size matter? Energy Journal, 36(3), 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Apergis, N., & Miller, S. M. (2009). Do structural oil-market shocks affect stock prices? Energy Economics, 31(4), 569–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arouri, M. E. H. (2011). Does crude oil move stock markets in Europe? A sector investigation. Economic Modelling, 28(4), 1716–1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basher, S. A., Haug, A. A., & Sadorsky, P. (2012). Oil prices, exchange rates and emerging stock markets. Energy Economics, 34(1), 227–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørnland, H. C. (2009). Oil price shocks and stock market booms in an oil exporting country. Scottish Journal of Political Economy, 56(2), 232–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buetzer, S., Habib, M. M., & Stracca, L. (2012). Global exchange rate configurations do oil shocks matter? European Central Bank. (No. 1442/June 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Caporin, M., & Mcaleer, M. (2012). Do we really need both bekk and dcc? a tale of two multivariate garch models. Journal of Economic Surveys, 26(4), 736–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chancharat, S., & Butda, J. (2021). Return and volatility linkages between bitcoin, gold price, and oil price: Evidence from diagonal BEKK–GARCH model. In Environmental, social, and governance perspectives on economic development in Asia (pp. 69–81). Emerald. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, S.-S., & Chen, H.-C. (2007). Oil prices and real exchange rates. Energy Economics, 29(3), 390–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doblas, M. P., Becaro, J. M. G., Sankar, J. P., Natarajan, V. K., Yoganandham, G., & Arumugasamy, G. (2024). Testing integrative models of the change behavior in the intention to adopt cryptocurrency. Sage Open, 14(2), 21582440241253542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engle, R. F., & Kroner, K. F. (1995). Multivariate simultaneous generalized ARCH. Econometric Theory, 11(1), 122–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filis, G., & Chatziantoniou, I. (2014). Financial and monetary policy responses to oil price shocks: Evidence from oil-importing and oil-exporting countries. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 42(4), 709–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foroutan, P., & Lahmiri, S. (2024). Connectedness of cryptocurrency markets to crude oil and gold: An analysis of the effect of COVID-19 pandemic. Financial Innovation, 10(1), 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, H. D., Hall, S. G., & Tavlas, G. S. (2017). A suggestion for constructing a large time-varying conditional covariance matrix. Economics Letters, 156, 110–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gkillas, K., Bouri, E., Gupta, R., & Roubaud, D. (2022). Spillovers in higher-order moments of crude oil, gold, and bitcoin. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 84, 398–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdi, B., Aloui, M., Alqahtani, F., & Tiwari, A. (2019). Relationship between the oil price volatility and sectoral stock markets in oil-exporting economies: Evidence from wavelet nonlinear denoised based quantile and Granger-causality analysis. Energy Economics, 80, 536–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, J. D. (1983). Oil and the macroeconomy since world war II. Journal of Political Economy, 91(2), 228–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hammoudeh, S., & Yuan, Y. (2008). Metal volatility in presence of oil and interest rate shocks. Energy Economics, 30(2), 606–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazgui, S., Sebai, S., & Mensi, W. (2022). Dynamic frequency relationships between bitcoin, oil, gold and economic policy uncertainty index. Studies in Economics and Finance, 39(3), 419–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., An, H., Gao, X., & Sun, X. (2017). Do oil price asymmetric effects on the stock market persist in multiple time horizons? Applied Energy, 185, 1799–1808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S., An, H., Huang, X., & Wang, Y. (2018). Do all sectors respond to oil price shocks simultaneously? Applied Energy, 227, 393–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, B. A., Elamer, A. A., & Abdou, H. A. (2025). The role of cryptocurrencies in predicting oil prices pre and during COVID-19 pandemic using machine learning. Annals of Operations Research, 345(2–3), 909–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilian, L., & Park, C. (2009). The impact of oil price shocks on the U.S. stock market. International Economic Review, 50(4), 1267–1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maghyereh, A., & Abdoh, H. (2022). COVID-19 and the volatility interlinkage between bitcoin and financial assets. Empirical Economics, 63(6), 2875–2901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natarajan, V. K., Abrar ul Haq, M., Akram, F., & Sankar, J. P. (2021). Dynamic relationship between stock index and asset prices: A long-run analysis. Journal of Asian Finance, Economics and Business, 8(4), 601–611. [Google Scholar]

- Park, J., & Ratti, R. A. (2008). Oil price shocks and stock markets in the U.S. and 13 European countries. Energy Economics, 30(5), 2587–2608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, S. B., & Veiga, H. (2013). Oil price asymmetric effects: Answering the puzzle in international stock markets. Energy Economics, 38, 136–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reboredo, J. C. (2012). Modelling oil price and exchange rate co-movements. Journal of Policy Modeling, 34(3), 419–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadorsky, P. (1999). Oil price shocks and stock market activity. Energy Economics, 21(5), 449–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Workman, D. (2023). Crude oil imports by country. Worlds Top Exports. Available online: https://www.worldstopexports.com/crude-oil-imports-by-country/ (accessed on 14 October 2023).

- Xiao, J., Zhou, M., Wen, F., & Wen, F. (2018). Asymmetric impacts of oil price uncertainty on Chinese stock returns under different market conditions: Evidence from oil volatility index. Energy Economics, 74, 777–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zha, R., Yu, L., Su, Y., & Yin, H. (2023). Dependences and risk spillover effects between Bitcoin, crude oil and other traditional financial markets during the COVID-19 outbreak. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 30(14), 40737–40751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-J., & Wei, Y.-M. (2010). The crude oil market and the gold market: Evidence for cointegration, causality and price discovery. Resources Policy, 35(3), 168–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| USA | CAN | UK | FRA | JAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PP | ADF | PP | ADF | PP | ADF | PP | ADF | PP | ADF |

| Bitcoin | −1.43 | −1.433 | −1.433 | −1.435 | −1.443 | −1.446 | −1.442 | −1.444 | −1.721 | −1.717 |

| Consumer Discretionary | −0.143 | −0.113 | −1.531 | −1.3 | −2.863 ** | −2.976 ** | −1.546 | −1.104 | −2.351 | −2.279 |

| Consumer Staples | −0.142 | −0.05 | −0.648 | −0.704 | −2.903 ** | −2.913 ** | −1.09 | −0.694 | −2.15 | −2.219 |

| Energy | −1.914 | −1.958 | −2.605 *** | −2.42 | −1.688 | −1.681 | −2.473 | −2.18 | −1.676 | −1.696 |

| Financials | −1.084 | −1.053 | −1.51 | −1.249 | −2.26 | −2.284 | −2.146 | −2.247 | −2.686 *** | −2.591 *** |

| Gold | −0.806 | −0.839 | −0.802 | −0.833 | −0.807 | −0.837 | −0.804 | −0.837 | −0.955 | −1.041 |

| Health Care | −0.201 | −0.1 | −4.562 * | −4.456 * | −1.886 | −1.692 | −1.097 | −0.832 | −1.737 | −1.816 |

| Industrials | −1.008 | −0.823 | −0.885 | −0.509 | −1.243 | −1.159 | −1.632 | −1.393 | −1.534 | −1.82 |

| Information Technology | 0.247 | 0.391 | −0.363 | −0.192 | −2.249 | −2.29 | −0.515 | −0.259 | −0.598 | −0.677 |

| Materials | −1.242 | −0.977 | −1.985 | −1.947 | −1.532 | −1.267 | −1.009 | −0.818 | −2.179 | −2.411 |

| Nominal Effective Exchange Rate | −2.302 | −2.26 | −2.999 ** | −2.928 ** | −3.030 ** | −2.979 ** | −1.533 | −1.46 | −2.951 ** | −3.020 ** |

| Crude Oil | −2.182 | −2.703 *** | −2.199 | −2.637 *** | −2.195 | −2.632 *** | −2.2 | −2.641 *** | −2.542 | −2.752 *** |

| Real Estate | −2.347 | −2.301 | −2.418 | −2.476 | −2.986 ** | −3.042 ** | −2.032 | −1.959 | −3.304 ** | −3.094 ** |

| Telecommunication | −4.137 * | −3.797 * | −2.177 | −1.722 | −1.378 | −1.389 | −1.806 | −1.526 | −2.316 | −2.085 |

| Utilities | −1.749 | −1.224 | −1.081 | −0.433 | −2.113 | −2.113 | −2.714 *** | −2.958 ** | −1.083 | −1.11 |

| 3-Month Deposit Rate | −1.365 | −0.686 | −1.584 | −0.822 | −1.538 | −1.215 | −3.092 ** | −2.785 *** | −13.947 * | −5.308 * |

| USA | CAN | UK | FRA | JAP | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | PP * | ADF * | PP * | ADF * | PP * | ADF * | PP * | ADF * | PP * | ADF * |

| D(Bitcoin) | −41.185 | −21.338 | −41.437 | −21.645 | −41.125 | −21.548 | −41.314 | −21.611 | −39.806 | −20.119 |

| D(Consumer Discretionary) | −45.982 | −13.144 | −42.844 | −10.191 | −36.571 | −14.592 | −38.965 | −10.527 | −40.58 | −16.186 |

| D(Consumer Staples) | −45.078 | −11.831 | −40.756 | −12.285 | −40.062 | −10.286 | −39.665 | −15.927 | −40.814 | −20.642 |

| D(Energy) | −42.525 | −10.561 | −42.057 | −11.879 | −36.186 | −14.288 | −36.145 | −13.679 | −38.135 | −38.13 |

| D(Financials) | −46.533 | −10.343 | −42.307 | −11.004 | −38.008 | −14.359 | −36.796 | −11.883 | −38.755 | −22.962 |

| D(Gold) | −38.536 | −38.529 | −38.773 | −38.77 | −38.573 | −38.571 | −38.659 | −38.657 | −37.918 | −37.778 |

| D(Health Care) | −46.004 | −12.151 | −38.494 | −10.387 | −40.718 | −14.963 | −39.662 | −13.772 | −39.033 | −16.178 |

| D(Industrials) | −44.79 | −10.672 | −44.716 | −12.289 | −38.189 | −14.637 | −38.055 | −14.845 | −39.316 | −22.673 |

| D(Information Technology) | −49.252 | −11.251 | −40.51 | −9.177 | −39.762 | −14.303 | −39.54 | −15.405 | −39.437 | −26.077 |

| D(Materials) | −42.796 | −10.993 | −39.079 | −39.079 | −40.06 | −10.438 | −42.943 | −14.069 | −38.84 | −22.16 |

| D(Nominal Effective Exchange Rate) | −39.316 | −39.316 | −38.71 | −24.517 | −38.622 | −20.756 | −43.144 | −11.592 | −39.328 | −19.337 |

| D(Crude Oil) | −41.419 | −6.385 | −41.795 | −6.482 | −41.599 | −6.398 | −41.703 | −6.446 | −38.872 | −8.492 |

| D(Real Estate) | −42.677 | −10.453 | −38.374 | −13.64 | −33.725 | −14.402 | −37.525 | −10.749 | −34.586 | −11.437 |

| D(Telecommunication) | −44.452 | −11.528 | −46.659 | −9.366 | −38.537 | −14.68 | −40.702 | −14.021 | −40.566 | −10.915 |

| D(Utilities) | −44.535 | −10.304 | −42.363 | −13.396 | −39.5 | −12.211 | −37.384 | −13.26 | −37.584 | −16.526 |

| D(3-Month Deposit Rate) | −81.149 | −9.268 | −87.317 | −8.834 | −60.821 | −19.571 | −94.561 | −10.474 | −88.567 | −10.731 |

| Sector | Oil-Exporting Countries (USA, CAN) | Oil-Importing Countries (UK, FRA, JAP) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy-Intensive Sectors | ||

| Consumer Discretionary (CD) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Energy (EN) | Significant (+) | Significant (+) |

| Industrials (IND) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Materials (MAT) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Utilities (UTI) | Insignificant | Insignificant |

| Non-Energy-Intensive Sectors | ||

| Consumer Staples (CS) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Financials (FIN) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Health Care (HC) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Information Technology (IT) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Real Estate (RE) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Telecommunication (TEL) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Other Variables | ||

| Bitcoin (BTC) | Significant (+) | Insignificant |

| Gold (GOLD) | Significant (+) | Significant (+) |

| 3-Month Deposit Rate (IR) | Significant (−) | Insignificant |

| Nominal Effective Exchange Rate (NEER) | Insignificant | Insignificant |

| Volatility Relationship | Pre COVID-19—(Oil-Exporting) | Pre COVID-19—(Oil-Importing) | Intra COVID-19—(Oil-Exporting) | Intra COVID-19—(Oil-Importing) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oil—Sectoral Stock Indices | Significant (+) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Significant (+) | Significant (+) |

| Oil—Nominal Effective Exchange Rate | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) |

| Oil—3-month Deposit Rate | Significant (−) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Significant (−) | Ambiguous |

| Oil—Bitcoin | Significant (+) | Ambiguous (Contradictory) | Insignificant | Insignificant |

| Oil—Gold Price | Significant (+) | Significant (+) | Significant (+) | Significant (+) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Almutawa, S.; Hassan, H.; Sankar, J.P. Stock Market Returns and Crude Oil Price Volatility: A Comparative Study Between Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing Countries. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120713

Almutawa S, Hassan H, Sankar JP. Stock Market Returns and Crude Oil Price Volatility: A Comparative Study Between Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):713. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120713

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlmutawa, Salman, Hussein Hassan, and Jayendira P. Sankar. 2025. "Stock Market Returns and Crude Oil Price Volatility: A Comparative Study Between Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing Countries" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120713

APA StyleAlmutawa, S., Hassan, H., & Sankar, J. P. (2025). Stock Market Returns and Crude Oil Price Volatility: A Comparative Study Between Oil-Exporting and Oil-Importing Countries. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 713. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120713