1. Introduction

Prior research shows that firms’ financing activities provide important information about future stock performance. Equity issuers, including IPO and SEO firms, typically experience poor subsequent returns (

Ritter, 1991;

Loughran & Ritter, 1995;

Spiess & Affleck-Graves, 1995), while share repurchases are associated with positive long-term performance (

Ikenberry et al., 1995,

2000). Debt issuance exhibits similar patterns, with issuers of straight bonds, convertible bonds, or bank loans generally underperforming after issuance (

Spiess & Affleck-Graves, 1999;

Lee & Loughran, 1998;

Billett et al., 2006).

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) unify these separate findings by introducing a comprehensive measure of net external financing and show that it is strongly negatively related to future returns. Despite its importance, the external financing relation has rarely been examined outside the U.S., motivating our investigation of whether the

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) result also holds in the Korean market.

Korea provides an ideal setting to revisit this question for two reasons. First, its financial system integrates both bank-based and market-based financing channels (

Haw et al., 2014). Bank loans are largely relationship-oriented and rely heavily on private monitoring and credit assessment (

Petersen & Rajan, 1994). Banks use proprietary information accumulated through long-term relationships to evaluate borrowers, making lending decisions less affected by short-term market mispricing. Corporate bonds, by contrast, are issued in public markets and are therefore more exposed to investor sentiment and prevailing market conditions. Second, unlike the U.S. setting, Korean cash-flow statements separately disclose bond issuance and bank loans, enabling us to construct disaggregated measures of financing flows and directly test whether market-based and bank-based debt exhibit different post-issuance performance. This institutional feature makes Korea a particularly valuable setting for studying behavioral misvaluation across debt types.

Consistent with behavioral misvaluation and market-timing explanations, we find that firms with higher levels of external financing subsequently experience significantly lower stock returns. A hedge portfolio that buys firms in the lowest financing decile (net repurchasers) and sells firms in the highest financing decile (net issuers) earns an average annual return of approximately 12 percent (t = 3.11), positive in 26 of 30 sample years. Both equity and debt components contribute to this pattern, indicating that the anomaly operates broadly across financing sources. Moreover, bond-financed firms exhibit stronger post-financing underperformance than loan-financed firms, consistent with the greater sentiment sensitivity of market-based financing. In addition to stock return effects, we find that external financing is negatively associated with future operating performance. The coefficient on net external financing is −0.079 (t = −4.76) for one-year-ahead income and −0.031 (t = −3.86) for the long-term (two- to five-year) horizon, suggesting that external financing aligns with subsequent profitability declines rather than reflecting growth opportunities.

This study makes three contributions to the literature. First, to our knowledge, it is among the first studies to examine the external financing anomaly in an emerging-market context, thereby extending the scope of prior findings beyond developed markets. Second, it provides new evidence from Korea linking debt financing, specifically the distinction between bonds and loans, to stock returns. Third, by comparing market-based and bank-based financing, we offer further support for the behavioral interpretation of financing decisions and highlight how financing channels condition the strength of misvaluation effects. Together, these findings enrich our understanding of how corporate financing decisions interact with investor sentiment and market efficiency.

The remainder of this paper proceeds as follows.

Section 2 reviews the related literature and formulates the hypotheses.

Section 3 describes the data and methodology.

Section 4 presents the empirical results and discussion, and

Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review and Hypotheses

2.1. External Financing and Stock Returns

Extensive prior research examines how corporate financing activities convey information about firms’ valuations and future performance. Much of this work focuses on equity issuance, where firms raising new equity capital tend to experience poor subsequent stock returns.

Ritter (

1991) documents long-run underperformance following IPOs.

Loughran and Ritter (

1995) and

Spiess and Affleck-Graves (

1995) report similar findings for seasoned equity offerings (SEOs), suggesting that managers exploit temporary overvaluation when issuing new shares.

Ikenberry et al. (

1995,

2000) find that subsequent stock returns following share repurchases yield positive long-term returns in the US and Canada, respectively. Using a share-issuance measure,

Pontiff and Woodgate (

2008) show that annual net share issuance is negatively related to future stock returns. Taken together, these findings suggest that equity issuance decisions often coincide with periods of temporary overvaluation, leading to systematically lower subsequent returns for issuing firms.

A smaller stream of research examines debt financing, where similar underperformance patterns are observed following bond or long-term debt offerings. Both earlier and more recent evidence show that firms issuing debt tend to experience weaker stock-market performance. Issuers of straight bonds, convertible bonds, and bank loans display consistently lower subsequent returns (

Spiess & Affleck-Graves 1999;

Lee & Loughran 1998;

Billett et al. 2006). These findings suggest that both equity and debt issuance may reflect managerial timing behavior and investor sentiment. However, most prior studies analyze these channels in isolation, leaving open the question of how aggregate external financing jointly relates to future stock performance.

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) bridge this gap by introducing a comprehensive measure of net external financing that combines equity and debt flows. Consistent with the misvaluation view of

Ritter (

2003), which suggests that firms issue new securities when they are temporarily overvalued by the capital markets,

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) document a strong negative relation between this measure and subsequent stock returns.

Hardouvelis et al. (

2012) further confirm that the negative relation between external financing and future stock returns persists across different subsamples and remains robust to alternative model specifications. More recently,

Cao et al. (

2025) extend this framework by analyzing stock-price behavior around external financing and documenting distinct pre-issuance run-ups and post-issuance underperformance consistent with market misvaluation.

Cao et al. (

2025) also suggest the need for a more integrated approach to external financing, emphasizing that previous studies typically focus on individual categories of corporate financing transactions. Moreover, to the best of our knowledge, there are few studies in emerging markets for which the external financing anomaly is the main focus rather than a secondary component. This raises the question of whether the relation documented in

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) generalizes beyond the U.S., and addressing this gap motivates our replication and extension to an emerging-market context. Korea, in particular, provides an appropriate setting in which the external financing anomaly can be re-examined given its institutional features.

2.2. Hypothesis Formulation

Building on the evidence summarized in

Section 2.1, prior studies suggest that external financing activities convey information about firms’ future performance and stock valuation.

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) show that firms with greater net external financing subsequently earn lower stock returns, a pattern consistent with temporary overvaluation rather than compensation for risk. This prior evidence provides the basis for our first hypothesis. If investors overreact to the positive signals conveyed by financing events or misprice firms’ growth prospects, firms that raise more external capital are expected to underperform in the future.

H1: There is a negative association between net external financing and subsequent stock returns.

Equity and debt financing differ in their exposure to changes in firm value (

Harris & Raviv, 1991). Equity represents a residual claim that is more sensitive to changes in market valuations and potential mispricing (

Baker & Wurgler, 2002;

Myers & Majluf, 1984), whereas debt reflects contractual discipline, creditor monitoring, and prevailing credit conditions (

Merton, 1974;

Denis & Mihov, 2003). These structural differences imply that equity and debt may carry distinct information about firms’ future prospects and therefore warrant separate examination.

H2: There is a negative association between both equity financing and debt financing and subsequent stock returns.

Korea provides a useful setting in which to examine heterogeneity across debt types because its financial system incorporates both market-based and bank-based financing channels (

Haw et al., 2014). Bank loans are relationship-oriented and rely on private monitoring and credit assessment, which allows lenders to draw on proprietary information accumulated through ongoing interactions with borrowers (

Petersen & Rajan, 1994). As a result, lending decisions by banks are likely to be less influenced by short-term valuation pressures or investor sentiment. Corporate bonds, by contrast, are issued in public markets and are more exposed to market conditions and sentiment-driven demand (

Greenwood & Hanson, 2013). In addition, Korean cash-flow statements separately report bond financing and bank loans, allowing us to identify these channels directly. If market-based financing is more sensitive to sentiment while bank-based financing benefits from greater informational advantages and monitoring, the return predictability associated with external financing should differ across these two debt categories.

H3: The negative association between financing and subsequent stock returns is stronger for bond-financed firms than for loan-financed firms.

3. Data and Methodology

Consistent with

Bradshaw et al. (

2006), our empirical design, including portfolio construction, return measurement, and regression specifications, follows their methodology to ensure comparability.

3.1. Data and Variable Construction

The sample consists of Korean listed firms on the KOSPI and KOSDAQ markets from 1994 to 2023. Financial statement data are obtained from DataGuide and TS2000, and stock return data are retrieved from DataGuide. Following prior literature, firms in the financial sector and observations with missing data are excluded. To mitigate the influence of outliers, all continuous variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. Winsorization ensures that our results are not driven by a small number of extreme observations.

External financing variables are derived from the statement of cash flows. Net external financing (ΔXFIN) is defined as the sum of changes in equity and debt financing. The equity financing component (ΔEQUITY) equals cash inflows from equity issuance minus cash outflows for share repurchases and cash dividend payments, scaled by average total assets. The debt financing component (ΔDEBT) equals cash inflows from new long-term and short-term borrowings minus debt repayments.

We further decompose debt financing into bond financing (ΔBONDS) and loan financing (ΔLOANS) based on changes in bond and loan proceeds and repayments. Income variables measure operating income scaled by average total assets. Income

t represents current income, while Income

t+1 and Income

t+2,t+5 denote future short-term (t + 1) and long-term (t + 2 to t + 5 average) income, respectively. Annual stock returns are compounded buy-and-hold returns. The size-adjusted return SRET

t+1 equals the firm’s annual return minus the value-weighted benchmark return of firms in the same size decile. We control for firm size as it is one of the most well-documented characteristics associated with cross-sectional variation in returns.

Table 1 presents the variable definitions.

Consistent with

Bradshaw et al. (

2006), we construct our main external financing variables directly from the statement of cash flows. Specifically, ΔXFIN (net external financing), ΔEQUITY (equity financing), and ΔDEBT (debt financing) follow the definitions in

Bradshaw et al. (

2006),

Hardouvelis et al. (

2012), and

Cao et al. (

2025), who similarly measure financing flows as net cash inflows and outflows related to equity and debt activities scaled by average total assets.

Our decomposition of debt financing into ΔBONDS and ΔLOANS is motivated by Korean accounting standards, which separately disclose cash inflows and outflows related to bond issuance and bank borrowings. While prior U.S.-based studies do not provide this separation due to data limitations, our definition is conceptually consistent with earlier studies on debt issuance (

Spiess & Affleck-Graves, 1999;

Billett et al., 2006), which examine long-term public debt announcements and bank loan announcements separately. Hence, our ΔBONDS and ΔLOANS extend their approaches by incorporating the respective cash-flow-based definitions used in our setting.

The income variables (Income

t, Income

t+1, Income

t+2,t+5) follow the operating-performance measures used in

Bradshaw et al. (

2006), who also examine future profitability to assess whether external financing corresponds to growth opportunities or temporary misvaluation. Finally, our measure of size-adjusted stock returns (SRET

t+1), follows

Hardouvelis et al. (

2012) and

Bradshaw et al. (

2006), who compute buy-and-hold returns net of benchmark size decile returns. Together, these definitions allow direct comparability with prior studies while exploiting additional bond–loan disclosure in Korea to extend the literature.

3.2. Portfolio Formation and Return Measurement

Each fiscal year, firms are ranked by the level of net external financing or its components (ΔXFIN, ΔEQUITY, ΔDEBT, ΔBONDS, ΔLOANS) and assigned to ten portfolios (deciles). Portfolio returns are measured over the subsequent year (t + 1), beginning four months after the fiscal year-end, as the average size-adjusted buy-and-hold returns of firms within each decile. The hedge portfolio is defined as a zero-investment portfolio that takes a long position in the lowest decile (repurchase firms) and a short position in the highest decile (issuers). This portfolio-based approach provides the first empirical test of H1, H2, and H3.

3.3. Return Regressions: One and Three-Factor Models

We estimate both a one-factor market model and the Fama–French three-factor model to evaluate whether abnormal returns associated with external financing can be explained by standard risk exposures. The one-factor model represents the traditional CAPM-based benchmark widely used in the literature, including the original analyses of external financing-related anomalies (e.g.,

Bradshaw et al., 2006). The Fama–French three-factor model is one of the most established extensions of CAPM and has been shown to explain a substantial portion of cross-sectional return variation globally, including in Asian markets. Using these two benchmark models therefore allows us to maintain comparability with existing literature while ensuring robust and interpretable risk adjustments.

To operationalize this risk-adjustment approach, we estimate time-series regressions for each decile portfolio using both a one-factor market model and the

Fama and French (

1993) three-factor model. For the one-factor model, excess portfolio returns are regressed on the excess market return as in Equation (1).

To control for size and value effects, the three-factor specification is estimated as in Equation (2)

In both models, α represents the abnormal return (alpha) and the β’s denote factor loadings. The persistence of significant positive hedge-portfolio alphas after controlling for market, size, and value factors would indicate that the external financing anomaly is not fully explained by conventional risk exposures.

The persistence of significant hedge-portfolio alphas after controlling for market, size, and value factors provides additional evidence on H1, H2, and H3. These factor-model regressions allow us to assess whether the return differentials associated with H1, H2, and H3 reflect risk compensation or mispricing.

In contrast, the cross-sectional regressions that follow quantify these effects at the firm level, allowing us to estimate the economic magnitude of financing activities. Together, the factor models and cross-sectional regressions provide complementary evidence by separating risk-adjusted performance from firm-level return implications.

3.4. Cross-Sectional Regressions of Future Returns

To test whether external financing predicts subsequent stock performance, we estimate annual cross-sectional regressions of next-year size-adjusted returns (

SRETt+1) on measures of external financing. Equation (3) is the baseline specification to test H1.

To examine the sources of this effect, we decompose ΔXFIN into its components. Equation (4) separates equity and debt financing to test H2.

Equation (5) further disaggregates debt financing into bonds and loans to test H3. This specification represents one of the key extensions of our study beyond prior research.

3.5. Cross-Sectional Regressions of Future Income

To examine whether external financing predicts subsequent changes in firms’ operating performance, we estimate annual cross-sectional regressions of short-term and long-term income on current income and external financing measures. These tests evaluate whether financing activities coincide with growth opportunities or reflect temporary overvaluation.

The short-term specification is given in Equation (6):

and the long-term specification is expressed as Equation (7):

where Income

t+1 represents one-year-ahead operating income and Income

t+2,t+5 is the average operating income over fiscal years t + 2 through t + 5.

4. Empirical Results

4.1. Descriptive Statistics

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for key variables used in this study. The sample consists of 21,829 firm-year observations from Korean listed firms. The mean value of ΔXFIN (net external financing) is 0.06, with a median of 0.017, indicating that, on average, firms raise additional external funds. The mean values of ΔEQUITY (net equity financing) and ΔDEBT (net debt financing) are 0.034 and 0.027, respectively, showing that both equity and debt financing contribute meaningfully to total external financing. Within debt financing, ΔBONDS (net bond financing) and ΔLOANS (net loan financing) account for mean values of 0.011 and 0.016, respectively, suggesting that loan financing slightly dominates bond issuance.

Median values close to zero across financing components imply that most firms experience modest financing activity, with right-skewed distributions driven by a subset of firms undertaking large issuances. Mean Incomet and Incomet+1 are 0.03 and 0.027, respectively, showing a slight decline in profitability over time. The mean of SRETt+1 is 0.026 with a wide standard deviation of 0.746, reflecting substantial variation in future size-adjusted stock returns.

Overall, the descriptive statistics indicate that Korean sample firms generally exhibit positive but heterogeneous external financing activities, moderate profitability, and highly dispersed subsequent stock performance, consistent with the patterns documented by

Bradshaw et al. (

2006).

4.2. Portfolio Returns

Table 3 reports the mean annual size-adjusted stock returns for decile portfolios formed on different measures of external financing, namely ΔEQUITY, ΔDEBT, and ΔXFIN. Each year, firms are ranked according to the level of net external financing and assigned in equal numbers to ten portfolios, with “Lowest” representing net repurchasers (firms reducing external capital) and “Highest” representing net issuers (firms raising external capital). Future stock returns are measured over the subsequent 12 months beginning four months after the fiscal year-end and are adjusted for firm size using value-weighted returns of firms in the same size decile.

Table 3 shows a general inverse relationship between external financing and subsequent stock returns. Firms in the lowest external financing decile (net repurchasers) earn an average size-adjusted return of 2.1%, whereas firms in the highest decile (net issuers) experience an average return of −10.1%. The corresponding hedge portfolio, long in the lowest decile and short in the highest, generates an economically large and statistically significant annual return of approximately 12% (t = 3.11). Similar patterns emerge when examining the equity and debt components separately: firms in the lowest equity-financing decile (net equity repurchasers) earn 5.9%, while those in the highest decile (net equity issuers) record −9.1%; likewise, the lowest debt-financing decile (net debt repurchasers) yields 4.1%, compared with −7.0% for the highest decile (net debt issuers). Overall,

Table 3 provides strong evidence that Korean firms with higher external financing activity, whether through equity or debt, tend to exhibit lower future stock returns, consistent with H1 and H2.

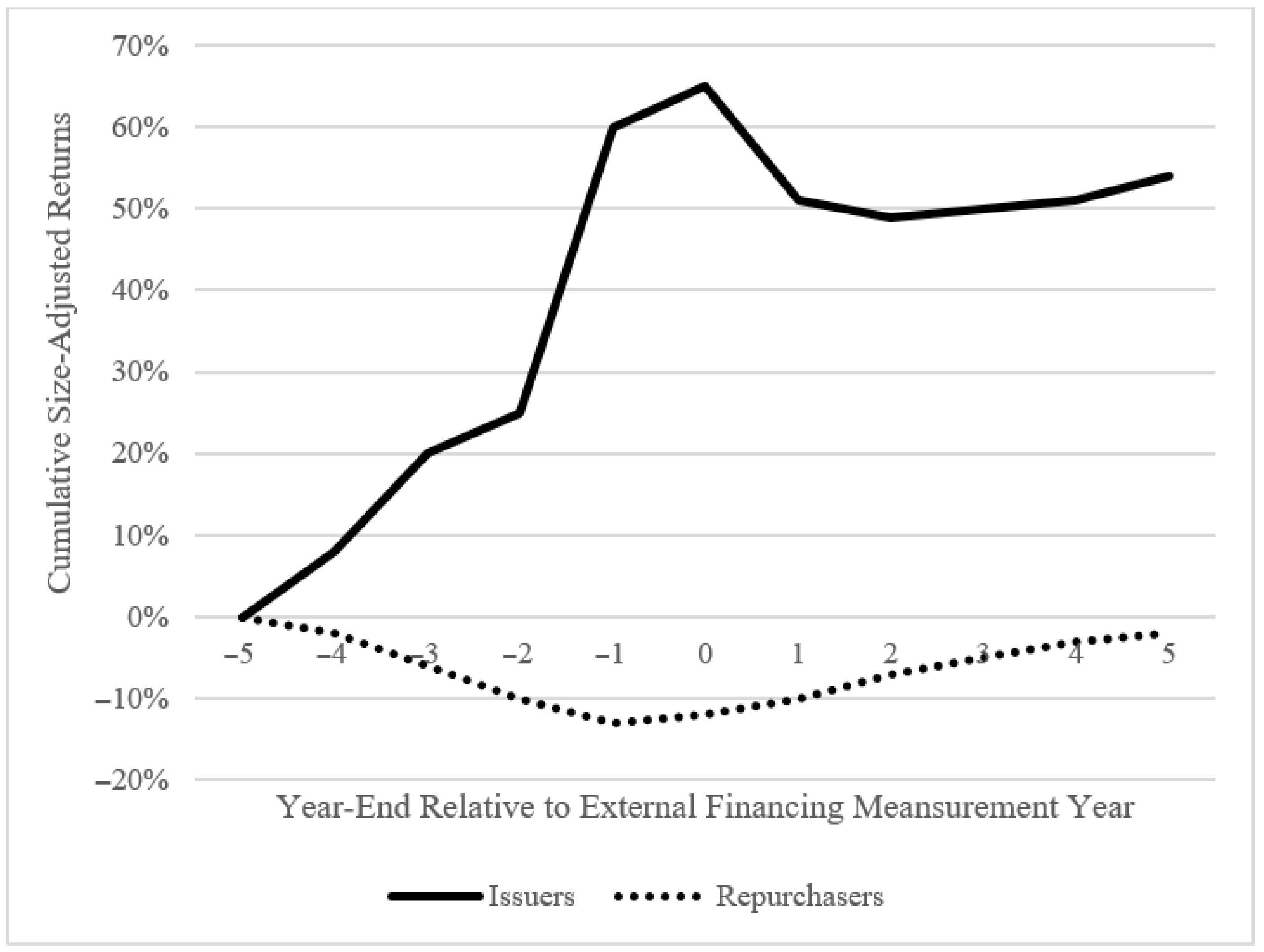

Figure 1 plots the cumulative size-adjusted stock returns for firms in the extreme external financing deciles (issuers versus repurchasers) over an eleven-year window centered on the measurement year (year 0). The figure shows a generally symmetric pattern around the financing year. Firms classified as issuers experience a pronounced run-up in cumulative returns before year 0, peaking at roughly 65%, while repurchasers show a gradual decline to about −15% over the same period. After the financing year, issuer returns flatten and partially reverse, whereas repurchaser returns recover steadily.

This pattern indicates that Korean firms tend to raise external capital following periods of strong prior performance and temporary overvaluation. The subsequent reversal in returns is consistent with the market-timing and misvaluation hypothesis, suggesting that managers issue securities when market sentiment is optimistic and prices are temporarily inflated. The similarity of this dynamic to that documented by

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) implies that the external financing anomaly extends beyond developed markets to the Korean setting.

4.3. Factor Model Results

To examine whether the negative relation between external financing and future stock returns can be explained by systematic risk,

Table 4 presents results from both the single-factor market model and the Fama–French three-factor model (

Fama & French, 1993). The risk-based view suggests that external financing may proxy for variations in systematic risk and expected returns. If this were true, controlling for common risk factors should eliminate abnormal returns.

Panel A reports the results from the single-factor market model for decile portfolios sorted by ΔXFIN. The estimated alphas display a generally monotonic decline, from 0.055 for the lowest decile (net repurchasers) to −0.126 for the highest decile (net issuers). The hedge portfolio, long in the lowest and short in the highest decile, earns a significant annual alpha of 18.1%, indicating that net issuers continue to underperform net repurchasers even after controlling for market risk.

Panel B extends the analysis using the Fama–French three-factor model. After controlling for the market (MKT), size (SMB), and value (HML) factors, alphas still display a generally monotonic downward pattern, from 0.024 for the lowest portfolio to −0.089 for the highest, yielding a significant hedge alpha of 11.3%. The persistence of significant positive hedge alphas after accounting for the three risk factors suggests that the external financing anomaly cannot be fully attributed to systematic risk.

Overall, consistent with H1 and H2, the results indicate that Korean firms with aggressive external financing earn significantly lower future returns. Even after controlling for standard risk factors, substantial abnormal returns remain, reinforcing the interpretation that the external financing anomaly primarily reflects market misvaluation rather than risk-based compensation.

4.4. Cross-Sectional Regressions

The factor-model tests and cross-sectional regressions offer complementary perspectives. The factor models evaluate whether financing-related return patterns can be explained by standard risk exposures. The persistence of significant alphas for the hedge portfolios indicates that standard risk adjustments cannot fully account for the return spread associated with external financing. In contrast, the cross-sectional regressions quantify the direct economic effect of financing decisions on future returns, providing firm-level estimates of how financing activities affect stock performance. Together, these approaches show not only that the external financing anomaly is robust to risk controls but also that its impact is economically meaningful.

Table 5 reports the cross-sectional regressions of subsequent size-adjusted stock returns (SRET₊

1) on measures of external financing. The specification follows

Bradshaw et al. (

2006), regressing future returns on contemporaneous financing activities to assess whether financing decisions predict subsequent performance. In Panel A, the coefficient on ΔXFIN is −0.190 (t = −2.57), indicating that firms engaging in greater external financing experience significantly lower future returns, consistent with H1. In economic terms, a one-standard-deviation increase in ΔXFIN corresponds to approximately a 2.6 percentage-point reduction (−0.190 × 0.137) in next-year returns, highlighting the economic relevance of this effect. When external financing is decomposed in Panel B, both ΔEQUITY and ΔDEBT load negatively and significantly in all specifications (β

1 ≈ −0.17; β

2 ≈ –0.25), consistent with H2, confirming that both equity and debt issuance are associated with weaker subsequent performance.

Panel C further separates debt financing into ΔBONDS and ΔLOANS to test whether the anomaly differs between market-based and bank-based debt channels. In the full specification including all variables, the coefficient on ΔBONDS is −0.138 (t = −2.36), and on ΔLOANS is −0.091 (t = −2.48). The difference between the two coefficients is statistically significant, indicating that the negative return–financing relation is stronger for bond-financed firms. This evidence supports H3, suggesting that market-based financing is more susceptible to behavioral mispricing, while bank-based financing is relatively insulated due to private monitoring and informational advantages. Overall, these results confirm that the external financing anomaly extends across both equity and debt markets, with its magnitude varying systematically by financing channel.

4.5. Additional Tests: Short-Term and Long-Term Profitability

Table 6 and

Table 7 present the time-series means and t-statistics from annual cross-sectional regressions examining whether external financing predicts firms’ subsequent profitability in both the short and long term. The results for short-term profitability (

Table 6, Panels A and B) show that ΔXFIN, as well as its components ΔEQUITY and ΔDEBT, are negatively and significantly related to future income, indicating that firms raising more external capital experience weaker near-term operating performance. For example, the coefficient on ΔXFIN in Panel A shows −0.079, implying that firms increasing external financing by one standard deviation experience a short-term decline in operating profitability of roughly 1.1 percentage points (−0.079 × 0.137). This pattern suggests that financing activities coincide with periods of temporary overvaluation rather than improvements in underlying fundamentals.

Similarly, the results for long-term profitability (

Table 7, Panels A and B) reveal that ΔXFIN, ΔEQUITY, and ΔDEBT remain negatively and significantly associated with future income averaged over years t + 2 to t + 5. For example, the coefficient on ΔXFIN (−0.031) implies that a one-standard-deviation increase in external financing is associated with a 0.4 percentage-point decline (−0.031 × 0.137) in long-term operating income. These findings extend the short-term evidence, implying that the negative profitability effect of external financing persists for multiple years after issuance.

Panels C of both tables further distinguish debt into ΔBONDS and ΔLOANS to examine whether these effects differ between market-based and bank-based debt channels. In the short-term regressions, the coefficient on ΔBONDS is −0.069 (t = −2.39), while that on ΔLOANS is –0.028 (t = −2.21); in the long-term regressions, ΔBONDS shows −0.055 (t = −2.92) and ΔLOANS −0.019 (t = −1.31). In both horizons, the absolute magnitude of the ΔBONDS coefficient exceeds that of ΔLOANS, and the differences are statistically significant. These results indicate that profitability deterioration is consistently stronger for bond-financed firms than for loan-financed ones, implying that sentiment-driven distortions are more pronounced in market-based channels, while the monitoring role of banks mitigates such effects.

Overall, the results from

Table 6 and

Table 7 reinforce and extend the evidence from

Table 5, confirming that external financing aligns with periods of temporary overvaluation and that its adverse effects on firm performance are both economically meaningful and persistent. The consistent post-issuance decline in profitability further suggests that investors fail to anticipate the deterioration in future fundamentals when valuing firms at the time of financing.

Across all empirical tests, a consistent pattern emerges. Firms that raise more external capital earn lower subsequent returns, both in portfolio sorts and cross-sectional regressions, and the economic magnitudes are meaningful. The hedge portfolio spread is approximately 12% per year, factor-model alphas remain economically large even after controlling for standard risk factors, and a one-standard-deviation increase in external financing reduces next-year returns by about 2–3 percentage points. Profitability tests further show that external financing is followed by sizable declines in future earnings, reinforcing that these patterns reflect temporary overvaluation rather than improvements in fundamentals. Taken together, the results provide evidence consistent with the external financing anomaly.

5. Conclusions

This study examines whether the external financing anomaly documented by

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) exists in an emerging-market setting. Using Korean firm-level data, we find a strong negative association between net external financing and subsequent stock returns. Firms that raise more external capital experience lower future returns, consistent with behavioral misvaluation and market-timing explanations. A hedge portfolio that buys firms in the lowest financing decile and sells firms in the highest decile delivers an economically and statistically significant annual return, providing clear evidence that the external financing anomaly exists in the Korean market.

When we disaggregate financing flows, both equity and debt issuance contribute to the negative relation between external financing and stock returns. Moreover, the magnitude of the return–financing relation differs across debt types: bond-financed firms exhibit stronger post-issuance underperformance than loan-financed firms. This contrast reflects an important institutional feature of Korea’s dual financial system, where market-based financing through corporate bonds is more sensitive to investor sentiment, whereas relationship-based bank lending benefits from private information and monitoring. External financing is also followed by a significant decline in operating profitability, indicating that investors do not fully anticipate future earnings deterioration. Taken together, these results show that financing decisions in Korea convey important information about temporary overvaluation and subsequent performance correction.

This study contributes to the literature in two ways. The primary contribution is to provide comprehensive evidence that the external financing anomaly documented by

Bradshaw et al. (

2006) also exists in Korea. A secondary contribution is that the magnitude of this relation varies across financing channels. The contrast between market-based bond financing and relationship-based bank lending can be examined in Korea because cash flow statements separately report bond and loan financing, unlike in the U.S. This distinction highlights mechanisms and institutional implications shaped by Korea’s dual financial system.

While these findings offer valuable insights into the Korean market, like most empirical work, this study also has certain limitations. The analysis focuses on a single country with institutional characteristics that may differ from those of other markets, so caution is needed when generalizing the results.

Future research could extend these findings by examining cross-country differences in financing structures, assessing how regulatory or institutional reforms influence the return–financing relation, or analyzing how external financing interacts with other capital market anomalies. Such work would further clarify how financing choices relate to market efficiency across different institutional environments.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.J.L.; methodology, S.J.L. and J.H.; validation, S.J.L. and J.H.; formal analysis, J.H.; investigation, S.J.L. and J.H.; resources, S.J.L. and J.H.; data curation, S.J.L. and J.H.; writing—original draft preparation, S.J.L. and J.H.; writing—review and editing, S.J.L. and J.H.; project administration, S.J.L.; funding acquisition, J.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of the data used for this study. The data were obtained from a commercial, third-party database under license and are available from the data vendor subject to their terms of use and payment of required fees.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Baker, M., & Wurgler, J. (2002). Market timing and capital structure. The Journal of Finance, 57(1), 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartram, S. M., & Grinblatt, M. (2018). Agnostic fundamental analysis works. Journal of Financial Economics, 128(1), 125–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Billett, M. T., Flannery, M. J., & Garfinkel, J. A. (2006). Are bank loans special? Evidence on the post-announcement performance of bank borrowers. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 41(4), 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, M. T., Richardson, S. A., & Sloan, R. G. (2006). The relation between corporate financing activities, analysts’ forecasts and stock returns. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 42(1–2), 53–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M., Martin, J. S., & Yao, Y. (2025). Understanding stock price behavior around external financing. Journal of Corporate Finance, 91, 102730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denis, D. J., & Mihov, V. T. (2003). The choice among bank debt, non-bank private debt, and public debt: Evidence from new corporate borrowings. Journal of Financial Economics, 70(1), 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (1993). Common risk factors in the returns on stocks and bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 33(1), 3–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, G., Giglio, S., & Xiu, D. (2020). Taming the factor zoo: A test of new factors. The Journal of Finance, 75(3), 1327–1370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenwood, R., & Hanson, S. (2013). Issuer quality and corporate bond returns. Review of Financial Studies, 26(6), 1483–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hardouvelis, G., Papanastasopoulos, G., Thomakos, D., & Wang, T. (2012). External financing, growth and stock returns. European Financial Management, 18(5), 790–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, M., & Raviv, A. (1991). The theory of capital structure. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 297–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haw, I. M., Lee, J. J., & Lee, W. J. (2014). Debt financing and accounting conservatism in private firms. Contemporary Accounting Research, 31(4), 1220–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, A., Huang, D., Li, J., & Zhou, G. (2023). Shrinking factor dimension: A reduced-rank approach. Management Science, 69(9), 5501–5522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, K., Xue, C., & Zhang, L. (2015). Digesting anomalies: An investment approach. The Review of Financial Studies, 28(3), 650–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenberry, D. L., Lakonishok, J., & Vermaelen, T. (1995). Market underreaction to open market share repurchases. Journal of Financial Economics, 39(2–3), 181–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikenberry, D. L., Lakonishok, J., & Vermaelen, T. (2000). Stock repurchases in Canada: Performance and strategic timing. The Journal of Finance, 55(5), 2373–2397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, I., & Loughran, T. (1998). Performance following convertible bond issuance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 4(2), 185–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, T., & Ritter, J. R. (1995). The new issues puzzle. The Journal of Finance, 50(1), 23–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merton, R. C. (1974). On the pricing of corporate debt: The risk structure of interest rates. The Journal of Finance, 29(2), 449–470. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Myers, S. C., & Majluf, N. S. (1984). Corporate financing and investment decisions when firms have information that investors do not have. Journal of Financial Economics, 13(2), 187–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, M. A., & Rajan, R. G. (1994). The benefits of lending relationships: Evidence from small business data. The Journal of Finance, 49(1), 3–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pontiff, J., & Woodgate, A. (2008). Share issuance and cross-sectional returns. The Journal of Finance, 63(2), 921–945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J. R. (1991). The long-run performance of initial public offerings. The Journal of Finance, 46(1), 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ritter, J. R. (2003). Investment banking and securities issuance. In G. M. Constantinides, M. Harris, & R. M. Stulz (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of finance (Vol. 1, pp. 255–306). North-Holland. [Google Scholar]

- Spiess, D. K., & Affleck-Graves, J. (1995). Underperformance in long-run stock returns following seasoned equity offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 38(3), 243–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spiess, D. K., & Affleck-Graves, J. (1999). The long-run performance of stock returns following debt offerings. Journal of Financial Economics, 54(1), 45–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).