Green Bond Pricing: A Comprehensive Review of the Empirical Literature

Abstract

1. Introduction

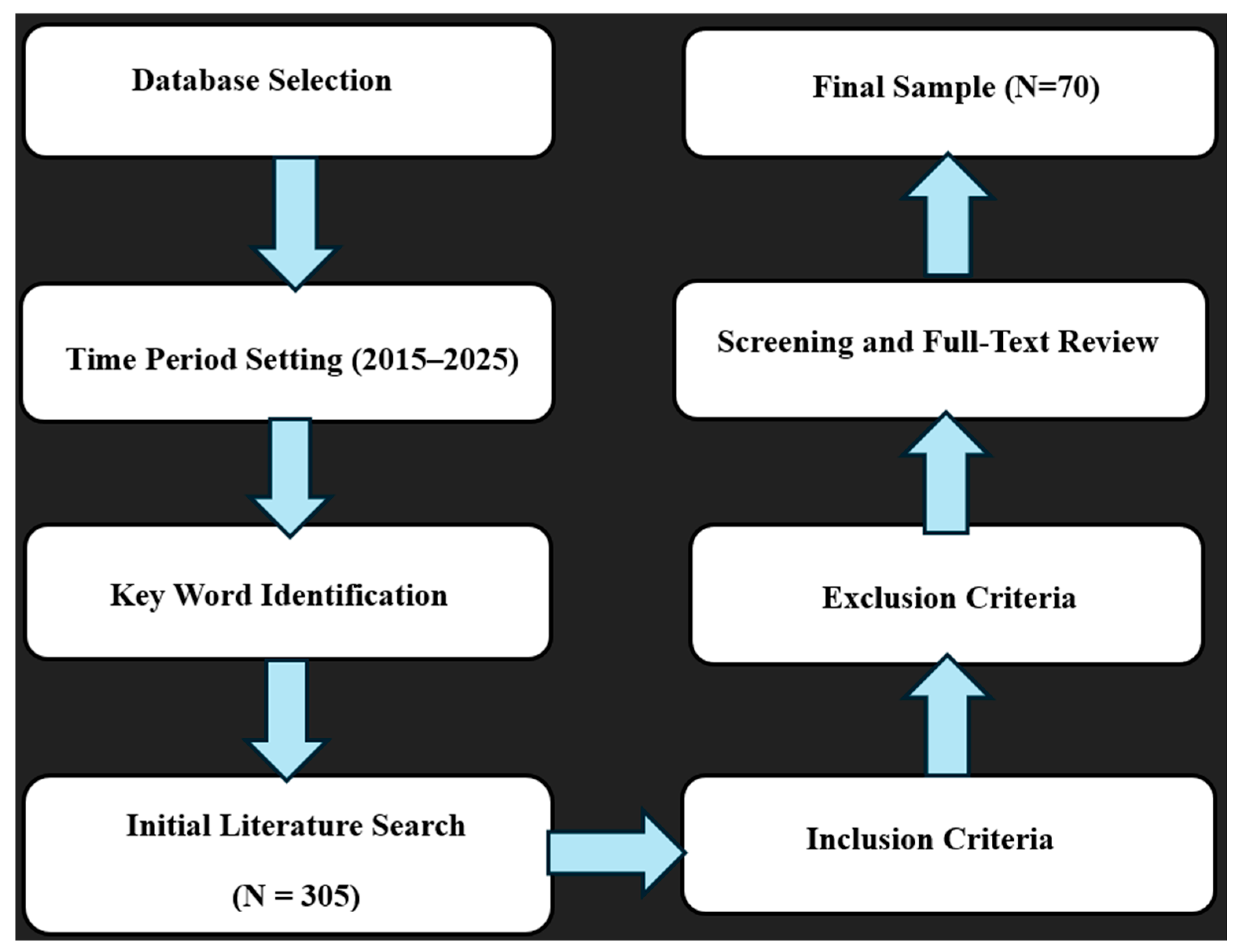

2. Research Method3

2.1. Literature Review Methodology

- (1)

- The inclusion criteria included:

- Studies focusing on the yield or price difference between green bonds and conventional bonds.

- Providing specific quantitative estimates of the green premium (e.g., spreads expressed in basis points).

- Using data on bonds issued in the actual market, covering the primary market, secondary market, or both.

- Clearly stating the data source and empirical methodology.

- Article types included: published journal articles, high-quality working papers, and policy research reports published by authoritative institutions.

- (2)

- The exclusion criteria included:

- Literature that did not involve price or yield analysis but instead focused on theoretical analysis (e.g., policy impact, status of green bond development, market structure, etc.).

- Literature only provides information such as green bond definitions, ratings, and certification mechanisms, but does not provide premium estimates.

- Literature with incomplete or untraceable data or methods, or purely theoretical in nature.

- Literature that focused on other green financial products (e.g., green funds, ESG indices, etc.) rather than green bonds.

- Non-official publications or articles of lower academic quality (e.g., master’s theses) are excluded.

2.2. Data Sources of Previous Literature

- Mainstream academic databases (e.g., Web of Science).

- Open-access academic search engines (e.g., Google Scholar).

- Professional publishing platforms and journal websites (including Elsevier, Springer, Taylor & Francis Online, and journals with high coverage of green bond research, such as Energy Economics, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, and Finance Research Letters).

2.3. Review Questions and Hypotheses

3. Geographical Trends in Green Bond Pricing Research

3.1. Global

3.2. U.S.

3.3. EU

3.4. Asia Pacific

3.5. AU

4. Data Sources and Matching Method Utilized in Existing Literature

4.1. Green Bond Database

4.2. Green Bond Study Matching Method

5. Discussion

5.1. Region

5.2. Primary vs. Secondary Market

5.3. Time Period

5.4. Size of Green Bond Issuance

5.5. Green Bond Database and Matching Method

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Green Bond Pricing Literature by Region

| Author(s) (Year) | Market Segment | Time Span | Study Region | Premium Dimension | Data | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Zerbib (2019) | Secondary market | 2013–2017 | Global | −2 bps | Bloomberg | Matching method, Fixed effect panel regression |

| MacAskill et al. (2021) | Primary & Secondary market | n.a. | Global | −1 to −9 bps | n.a. | Systematic literature review |

| Nanayakkara and Colombage (2019) | Secondary market | 2016–2017 | Global | −63 bps | Bloomberg, FRED, OECD | Panel data regression with a hybrid model |

| Dorfleitner et al. (2022) | Secondary market | 2011–2020 | Global | 0.95 bps | Bloomberg, CBI | Panel data regression with a hybrid model |

| Hachenberg and Schiereck (2018) | Secondary market | 2015–2016 | Global | −3.38 bps for A-rated bonds | Bloomberg | OLS regression method |

| Löffler et al. (2021) | Primary & Secondary market | 2007–2019 | Global | −15 to −20 bps | Bloomberg, Refinitiv Eikon, Thomson Reuters, issuer websites | Matching Method, a probit model, the coarsened exact matching (CEM) |

| Ehlers and Packer (2017) | Primary & Secondary market | 2014–2017 | Global | −18 bps | Bloomberg, Climate Bonds Initiative | Matched-pair analysis, spread comparison at issuance |

| Agliardi and Agliardi (2019) | Primary market | 2017–2024 | Global | 6.89 bps | Enel | Structural credit risk model + numerical computation + case study |

| Ben Slimane et al. (2020). | Secondary market | 2016–2020 | Global | −2 to −4.7 bps | Bloomberg | Top-down synthetic portfolio OAS comparison + Bottom-up intra-curve spread matching + Panel regression with controls |

| Benincasa et al. (2022) | Primary market | 2012–2021 | Global | −4.9 to −8.7 bps | Bloomberg | OLS regressions with fixed effects, robustness checks |

| Hyun et al. (2021) | Secondary market | 2014–2017 | Global | Labeled green bonds yield ≈ 24–36 bps lower than unlabeled green bonds | Bloomberg | Propensity Score Matching, Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM), OLS regression method |

| Caramichael and Rapp (2024) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2021 | Global | −3 bps | Bloomberg | Matching + Fixed-effects panel regressions |

| van Keppel (2019) | Secondary market | 2018–2019 | Global | −1.5 bps | Bloomberg and Thomson Reuters | Matching Methodios regressions method |

| Flammer (2021) | Primary market | 2013–2018 | Global | 0 bps | Bloomberg | Event study + Matching method |

| Lau et al. (2022) | Secondary market | 2014–2019 | Global | −1.2 bps | International Securities Identification Numbers (ISIN) | Synthetic conventional bond construction (triplets, interpolation), panel regressions with two-way fixed effects (entity and time FE), decomposition into market greenium (time-varying) and idiosyncratic greenium (bond-specific) |

| Flottmann et al. (2025) | Primary & Secondary market | 2007–2025 | Global | −1 to −6 bps | n.a. | Systematic literature review |

| Eskildsen et al. (2024) | Primary & Secondary market | 2014–2021 | Global | −6 bps | Bloomberg, Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) | propensity Score Matching (PSM) + Mahalanobis matching + panel regressions with bond & time FE, liquidity and macro controls |

| D. Y. Tang and Zhang (2020) | Primary & Secondary market | 2007–2017 | Global | −6.9 bps | The Climate Bond Initiative (CBI), Bloomberg | matched bond yield spread regressions, diff-in-diff for institutional ownership, panel regressions for stock liquidity |

| Caramichael and Rapp (2024) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2021 | Global | −3 bps | Bloomberg | Matching + Fixed-effects panel regressions + event study |

| Okafor et al. (2024) | Primary market | 2007–2022 | Global | +1 to +5 bps | Bloomberg MSCI green bond index, Sustainable Finance, Climate mitigation, Innovative Clean Technologies, and Energy Efficiency | OLS regression and fixed-effects panel regressions, using the matched pairs approach |

| Bachelet et al. (2019) | Secondary market | 2013–2017 | Global | 2.1 to 5.9 bps | Bloomberg | One-to-one matching, OLS and FE regressions on daily yield differentials; robustness with bootstrapping & Tobit models |

| Immel et al. (2021) | Secondary market | 2007–2019 | Global | −8 to −14 bps | Bloomberg | OLS regressions on bond spreads with controls |

| Wu (2022) | Secondary market | China: 2016–2019/Global: 2010–2019 | China & Global | China: 3.4 bps/Global: 12.5 bps | Xinhua Green Bond Database, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, and CBI | Event study, Matching method, Two-layer regression, Panel regressions with fixed effects |

| Østerud and Rasmussen (2019) | Secondary market | 2017–2019 | Global | −1.74 bps | Eikon, CBI | Constructed synthetic conventional bonds, Yield spread regression with liquidity proxy, Fixed effects panel regression |

| Schmitt (2017) | Secondary market | 2015–2017 | Global | −3.2 bps | Bloomberg | Construct synthetic conventional bond yield curves using Nelson–Siegel and Nelson–Siegel–Svensson (NSS) parametric models, Fixed-effects regressions with liquidity proxies, and Determinant analysis. |

| Hyun et al. (2020) | Global | |||||

| Caramichael and Rapp (2022) | Primary market | 2014–2021 | Global | −8 bps | Bloomberg, Refinitiv Workspace | Large-scale panel regressions with issuer × year fixed effects, controls for bond characteristics, yield curves, volatility, and credit spreads; robustness checks with oversubscription and bond index inclusion |

| Fatica et al. (2021) | Primary market | 2007–2018 | Global | a negative greenium for supranational (~−80 bps) and corporates (~−22 bps). Supranational ≈ −80 bps; Corporates ≈ −22 bps; Financials ≈ 0 | Dealogic DCM | OLS regressions on issuance yield spreads with controls, subsample by issuer type, robustness with alternative spread measures |

| Liaw (2020) | Primary & Secondary market | 2007–2019 | Global | n.a. | Systematic literature review | |

| Cortellini and Panetta (2021) | Primary & Secondary market | 2007–2020 | Global | n.a. | Systematic literature review | |

| Kapraun et al. (2021) | Primary & Secondary market | 2009–2021 | Global | not significant | Bloomberg, Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI) | Panel regressions of yields at issuance (primary) and yields to maturity (secondary), Matched bond pairs analysis |

| Bhutta et al. (2022) | Primary & Secondary market | Global | n.a. | Systematic literature review | ||

| Liu (2024) | Secondary market | 2011–2019 | Global | −11 bps | Bloomberg | Panel regressions with bond fixed effects, PS Matched sample regression |

| Author(s) (Year) | Market Segment | Time Span | Study Region | Premium Dimension | Data | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baker et al. (2022) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2018 | US | −5 to −9 bps | Refinitiv, Mergent, MSRB, EMMA | OLS regressions with bond fixed effects |

| Hyun et al. (2020) | Secondary market | 2010–2017 | US | −6 bps | Mergent FISD, MSRB, CBI | Matching Method, OLS regression method |

| Partridge and Medda (2018) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2018 | US | −4 bps | EMMA MSRB | Yield curve analysis |

| Baker et al. (2018) | Primary market | 2010–2016 | US | −6 bps | Refinitiv, Mergent, MSRB, EMMA | Matching Method, OLS regression method |

| Singh et al. (2024) | Primary market | 2014–2023 | US | −2.7 to −6.9 bps | Bloomberg | Propensity Score Matching + OLS regression |

| Partridge and Medda (2020) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2018 | US | Primary: 0–1 bps/Secondary: −4–5 bps | Issuer disclosures | Matched-pair analysis |

| Karpf and Mandel (2018) | Secondary market | 2010–2016 | US | −7.8 bps | Bloomberg | Yield curve, Mixed regression model |

| Kanamura (2025) | Secondary market | 2014–2022 | US & EU | −2 to −4 bps on average/−0.96 bps (US) and −0.73 bps (EU) | S&P Green Bond Index | Stochastic differential equation (SDE) model, Parameters estimated via Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE); GARCH (1,1) model |

| Karpf and Mandel (2018) | Secondary market | 2010–2016 | US | Early years (2010–2014): −7.8 bps/Recent years (2015–2016): 38 bps | Bloomberg Green Bond Database | Yield curve comparison, Oaxaca–Blinder decomposition |

| Larcker and Watts (2020) | Primary market | 2013–2018 | US | zero? Table 5 has identified the green premium | Bloomberg | Exact matched-pairs analysis |

| Author(s) (Year) | Market Segment | Time Span | Study Region | Premium Dimension | Data | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hinsche (2021) | Primary & Secondary market | 2014–2021 | EU | −0.7 bps | Bloomberg, Bundesbank, EADB Overview (25 May 2021) | Matching Method, OLS regressions with fixed effects |

| Jankovic et al. (2022) | Secondary market | 2016–2021 | EU | −6 bps (Transparency significantly lowers yields) | Climate Bonds Initiative (2022) | Panel data regression |

| Febi et al. (2018) | Secondary market | 2013–2016 | EU | −69.2 bps in 2016 | Thomson Reuters DataStream, Amadeus | Fixed effects panel regression model |

| Gianfrate and Peri (2019) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2017 | EU | −5 to −13 bps | “Bond Radar” of Bloomberg | Propensity Score Matching + OLS regressions with controls for maturity, volume |

| Wongaree et al. (2025) | Primary & Secondary market | 2016–2021 | Asia and the EU | Asia-Pacific: −9 to −10 bps (primary), −38 to −39 bps (secondary)/Europe: no significant greenium (0) | Bloomberg | Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM), Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), cross-sectional regressions with controls |

| Kanamura (2025) | Secondary market | 2014–2022 | US & EU | −2 to −4 bps on average/−0.96 bps (US) and −0.73 bps (EU) | S&P Green Bond Index | Stochastic differential equation (SDE) model, Parameters estimated via Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE); GARCH (1,1) model |

| Claasen (2023) | Secondary market | 2007–2022 | EU | Issuer-specific: 0/Issuer-unspecific: −23 to −26 bps | Refinitiv Workspace | Exact matching, Fixed-effects panel regressions |

| Berland and Aass (2020) | Secondary market | 2017–2020 | EU | 0, no significant greenium? It shows (−0.7 bps)? | Reuters Eikon | Synthetic twin matching, Panel regressions with Fixed Effects, and Driscoll–Kraay robust SEs |

| Intonti et al. (2022) | Secondary market | 2017–2022 | EU | −10 bps | Thomson Reuters Eikon | Matching method, Panel regressions with FE, Cross-sectional OLS on determinants |

| Mendonça (2022) | Primary & Secondary market | 2013–2022 | France | Primary: −19.3 bps/Secondary: −21.7 bps | Bloomberg | Matching Method |

| Author(s) (Year) | Market Segment | Time Span | Study Region | Premium Dimension | Data | Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Li et al. (2022) | primary market | 2016–2020 | China | −8.4 bps | Wind, CSMAR, Chinabond | A multivariate regression model |

| Cao et al. (2021) | Primary market | 2016–2018 | China | n.a. | iFinD database | GLS (General Least Square) methods |

| Berdiev (2025) | Primary market | 2016–2023 | Japan | −7 to 17 bps | Japan Exchange Group | Multivariate regressions (bond & firm–year FE) + robustness via fixed-effects models, same-day issuance tests, and Mahalanobis nearest-neighbor matching |

| Wongaree et al. (2025) | Primary & Secondary market | 2016–2021 | Asia and the EU | Asia-Pacific: −9 to −10 bps (primary), −38 to −39 bps (secondary)/Europe: no significant greenium (0) | Bloomberg | Coarsened Exact Matching (CEM), Synthetic Minority Oversampling Technique (SMOTE), cross-sectional regressions with controls |

| Q. Wang et al. (2019) | Primary market | 2016–2018 | China | 173 bps | the China Financial Information Network green bond database, CSMAR; Wind | Multiple Regression Analysis |

| Q. Sheng et al. (2021) | Primary market | 2016–2018 | China | −7.8 bps | CSMAR Database, Xinhua Green Finance Database | Propensity Score Matching, OLS regressions with controls |

| Fu et al. (2024) | Primary market | 2016–2021 | China | −23 bps | Wind | Propensity Score Matching, Panel regressions model, mediating effect tested via Bootstrap |

| Hao and Zhou (2025) | Primary & Secondary market | 2017–2023 | China | −8.7 bps | Wind | OLS |

| Wu (2022) | Secondary market | China: 2016–2019/ Global: 2010–2019 | China & Global | China: 3.4 bps/Global: 12.5 bps | Xinhua Green Bond Database, Bloomberg, Thomson Reuters, and CBI | Event study, Matching method, Two-layer regression, Panel regressions with fixed effects |

| Janda et al. (2022) | Secondary market | 2016–2020 | China | −1.8 bps | Thomson Reuters Refinitiv Eikon database and the Chinese iFind database | Matching method, Panel fixed-effects regressions of yield spread with liquidity proxy, Step-2 OLS regressions on determinants |

| Su and Lin (2022) | Secondary market | 2016–2021 | China | 28.14 bps | China Stock Market & Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) | Portfolio-based liquidity-sorted analysis, Pooled regressions on 9 proxies, Robustness checks |

| D. Sheng and Montgomery (2025) | Primary market | 2011–2022 | China | −12 to −31 bps | the China Stock Market and Accounting Research Database (CSMAR) and the Choice databases | OLS regressions on bond coupon rates with bond/issuer controls, Difference-in-differences (DID) around 2019 policy revision, Robustness with propensity score matching (PSM) and pooled samples |

| Lian and Hou (2024) | Primary market | 2018–2021 | China | −10 to −12 bps | The Wind Economic Database and corporate financial reports | Two-stage panel estimation, Matching method |

| Alexander and Jayawardhana (2025) | Primary & Secondary market | 2016–2024 | AU | 2 bps | Bloomberg, RBA | Matching Method |

| Verma and Agarwal (2020) | Primary market | 2015–2018 | India | CBI | SWOC Analysis | |

| Abhilash et al. (2023) | Primary market | 2015–2022 | India | −32 bps | Bloomberg, Climate Bonds Initiative | a panel regression technique with a random effect model |

| I. Tang et al. (2025) | equity market | 2010–2023 | AU | 118% | LSEG ESG database | OLS regressions |

Appendix B. Comparison of Matching and Regression Methods for Estimating Green Bond Premiums

| Method | How it Works for Green Bond Pricing | Advantages | Drawbacks | Use Conditions/Situations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PSM (Propensity Score Matching) | Matches each green bond with a conventional bond with similar characteristics (issuer, maturity, rating) to estimate the green bond premium via spread differences | Reduces selection bias; easy to implement; widely used in green bond studies | Only controls for observed variables; sensitive to propensity model specification; may lose sample size | Suitable when green bond issuance is non-random and sufficient covariates are available |

| CEM (Coarsened Exact Matching) | Coarsens covariates (e.g., rating, sector, maturity) and matches green and conventional bonds exactly within bins to calculate spread differences | Ensures better balance across key covariates; reduces dependence on model assumptions | Requires coarsening decisions; may discard large portions of data | Useful when precise control over matching covariates is critical for premium estimation |

| OLS & DID (Difference-in-Differences) | Regresses bond yields on green bond indicator, controlling for bond and issuer characteristics; DID uses pre- and post-issuance yields to isolate treatment effect (green premium) | Controls for time-invariant unobserved factors; interpretable coefficient as premium | Requires parallel trends assumption; sensitive to omitted variables and functional form | Appropriate for panel or repeated cross-section data where yields for matched green and conventional bonds are observed over time |

| 1 | According to the Climate Bonds Initiative (CBI), green bond issuance volumes continue to expand, with issuers including sovereign entities, local governments, corporations, and financial institutions, and issuance locations covering Europe, the Americas, Asia Pacific, and global markets. |

| 2 | In this study, “region” refers to the geographical market in which the green bonds were issued and analyzed, rather than the location of the authors or their institutions. |

| 3 | In this paper, the term “method” is used in two contexts: in Section 2, it refers to the literature review methodology for selecting and analyzing studies, while in Section 4.2, it refers to bond-level pricing methods, such as matching green bonds with comparable conventional bonds to estimate the green premium. |

References

- Abhilash, A., Shenoy, S. S., Shetty, D. K., & Kamath, A. N. (2023). Do bond attributes affect green bond yield? Evidence from Indian green bonds. Environmental Economics, 14(2), 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agliardi, E., & Agliardi, R. (2019). Financing environmentally-sustainable projects with green bonds. Environment and Development Economics, 24(6), 608–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexander, K., & Jayawardhana, S. (2025, January). Australia’s sovereign ‘green’ labelled debt. RBA Bulletin. Available online: https://www.rba.gov.au/publications/bulletin/2025/jan/australias-sovereign-green-labelled-debt.html (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Bachelet, M. J., Becchetti, L., & Manfredonia, S. (2019). The green bonds premium puzzle: The role of issuer characteristics and third-party verification. Sustainability, 11(4), 1098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M., Bergstresser, D., Serafeim, G., & Wurgler, J. (2018). Financing the response to climate change: The pricing and ownership of US green bonds. No. w25194. National Bureau of Economic Research. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, M., Bergstresser, D., Serafeim, G., & Wurgler, J. (2022). The pricing and ownership of US green bonds. Annual Review of Financial Economics, 14(1), 415–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, E., Fu, J., Mishra, M., & Paranjape, A. (2022). Different shades of green: Estimating the green bond premium using natural language processing. Swiss Finance Institute Research Paper Series 22–64. Swiss Finance Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Ben Slimane, M., Mahtani, V., & da Fonseca, D. (2020). Facts and fantasies about the green bond premium. Amundi Working Paper No. 102-2020. Amundi. [Google Scholar]

- Berdiev, U. (2025). What shapes greenium in bond markets? Evidence from Japan. Economic Modelling, 151, 107159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berland, A. R., & Aass, B. (2020). The Green Bond Premium—Does it appear in the European bond market? Handelshøyskolen BI. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, U. S., Tariq, A., Farrukh, M., Raza, A., & Iqbal, M. K. (2022). Green bonds for sustainable development: Review of literature on development and impact of green bonds. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 175, 121378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, X., Jin, C., & Ma, W. (2021). Motivation of Chinese commercial banks to issue green bonds: Financing costs or regulatory arbitrage? China Economic Review, 66, 101582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramichael, J., & Rapp, A. C. (2022). The green corporate bond issuance premium. International Finance Discussion Paper No. 1346. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caramichael, J., & Rapp, A. C. (2024). The green corporate bond issuance premium. Journal of Banking & Finance, 162, 107126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, J. (2017). Growing the US green bond market. California State Treasurer. [Google Scholar]

- Claasen, M. (2023). Vanishing anomaly or persisting force? Exploring the temporal variability of the green bond premium [Master’s thesis, Maastricht University]. Available online: https://core.ac.uk/outputs/621578854 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (2019). Green bonds: Global state of the market 2019. Climate Bonds Initiative. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/data-insights/publications/green-bonds-global-state-market-2019 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (2022). Sustainable debt: Global state of the market 2022. Climate Bonds Initiative. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/data-insights/publications/global-state-market-report-2022 (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Cortellini, G., & Panetta, I. C. (2021). Green bond: A systematic literature review for future research agendas. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 14(12), 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dorfleitner, G., Utz, S., & Zhang, R. (2022). The pricing of green bonds: External reviews and the shades of green. Review of Managerial Science, 16(3), 797–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehlers, T., & Packer, F. (2017). Green bond finance and certification. BIS Quarterly Review, 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Eskildsen, M., Ibert, M., Jensen, T. I., & Pedersen, L. H. (2024). In search of the true greenium. SSRN Electronic Journal. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fatica, S., Panzica, R., & Rancan, M. (2021). The pricing of green bonds: Are financial institutions special? Journal of Financial Stability, 54, 100873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Febi, W., Schäfer, D., Stephan, A., & Sun, C. (2018). The impact of liquidity risk on the yield spread of green bonds. Finance Research Letters, 27, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flottmann, C., Köchling, G., Neukirchen, D., & Posch, P. (2025). Green debt: A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Management Review Quarterly, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y., He, L., Liu, R., Liu, X., & Chen, L. (2024). Does heterogeneous media sentiment matter the ‘green premium’? An empirical evidence from the Chinese bond market. International Review of Economics & Finance, 92, 1016–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gianfrate, G., & Peri, M. (2019). The green advantage: Exploring the convenience of issuing green bonds. Journal of Cleaner Production, 219, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hachenberg, B., & Schiereck, D. (2018). Are green bonds priced differently from conventional bonds? Journal of Asset Management, 19(6), 371–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, Y., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Green bond issuance premium effect and investor incentive effect. Finance Research Letters, 85, 108042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinsche, I. C. (2021). A greenium for the next generation EU green bonds analysis of a potential green bond premium and its drivers. Center for Financial Studies Working Paper, 663, 20201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyun, S., Park, D., & Tian, S. (2020). The price of going green: The role of greenness in green bond markets. Accounting & Finance, 60(1), 73–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hyun, S., Park, D., & Tian, S. (2021). Pricing of green labeling: A comparison of labeled and unlabeled green bonds. Finance Research Letters, 41, 101816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immel, M., Hachenberg, B., Kiesel, F., & Schiereck, D. (2021). Green bonds: Shades of green and brown. Journal of Asset Management, 22(2), 96–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intonti, M., Serlenga, L., Ferri, G., & De Leonardis, M. (2022). The green bond premium: A comparative analysis. CERBE Working Paper No. 40. CERBE Center for Relationship Banking and Economics. Available online: https://repec.lumsa.it/wp/wpC40.pdf (accessed on 27 November 2025).

- Janda, K., Kortusova, A., & Zhang, B. (2022). Green bond premiums in the Chinese secondary market. IES Working Paper No. 20/2022. Institute of Economic Studies, Charles University. [Google Scholar]

- Jankovic, I., Vasic, V., & Kovacevic, V. (2022). Does transparency matter? Evidence from panel analysis of the EU government green bonds. Energy Economics, 114, 106325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanamura, T. (2025). Stochastic behavior of green bond premiums. International Review of Financial Analysis, 97, 103836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapraun, J., Latino, C., Scheins, C., & Schlag, C. (2021). (In)-credibly green: Which bonds trade at a green bond premium? Proceedings of Paris December 2019 Finance Meeting EUROFIDAI—ESSEC. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3347337 (accessed on 27 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Karpf, A., & Mandel, A. (2018). The changing value of the ‘green’ label on the US municipal bond market. Nature Climate Change, 8(2), 161–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larcker, D. F., & Watts, E. M. (2020). Where’s the greenium? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 69(2–3), 101312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, P., Sze, A., Wan, W., & Wong, A. (2022). The economics of the Greenium: How much is the world willing to pay to save the earth? Environmental and Resource Economics, 81(2), 379–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q., Zhang, K., & Wang, L. (2022). Where’s the green bond premium? Evidence from China. Finance Research Letters, 48, 102950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lian, J., & Hou, X. (2024). Navigating geopolitical risks: Deciphering the greenium and market dynamics of green bonds in China. Sustainability, 16(15), 6354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liaw, K. T. (2020). Survey of green bond pricing and investment performance. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 13(9), 193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L. (2024). Exploring the relationship between green bond pricing and ESG performance: A global analysis. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Löffler, K. U., Petreski, A., & Stephan, A. (2021). Drivers of green bond issuance and new evidence on the “greenium”. Eurasian Economic Review, 11(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacAskill, S., Roca, E., Liu, B., Stewart, R. A., & Sahin, O. (2021). Is there a green premium in the green bond market? Systematic literature review revealing premium determinants. Journal of Cleaner Production, 280, 124491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendonça, C. M. T. (2022). Are corporate green bonds issued and traded at a premium? Evidence from France [Master’s thesis, Universidade NOVA de Lisboa]. [Google Scholar]

- Nanayakkara, M., & Colombage, S. (2019). Do investors in green bond market pay a premium? Global evidence. Applied Economics, 51(40), 4425–4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okafor, A., Adusei, M., & Edo, O. C. (2024). Effects of the utilization of green bonds proceeds on green bond premium. Journal of Cleaner Production, 469, 143131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Østerud, E., & Rasmussen, A. S. (2019). The green bond premium: An extension with use of proceeds. HANDELSHØYSKOLEN BI. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., & Chou, R. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Partridge, C., & Medda, F. (2018). Green premium in the primary and secondary US municipal bond markets. Available online: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3237032 (accessed on 27 November 2025). [CrossRef]

- Partridge, C., & Medda, F. R. (2020). Green bond pricing: The search for greenium. Journal of Alternative Investments, 23(1), 49–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitt, S. J. (2017). A parametric approach to estimate the green bond premium [Master’s thesis, NOVA—School of Business and Economics & INSPER]. [Google Scholar]

- Sheng, D., & Montgomery, H. A. (2025). The financial benefits of going green: An analysis of bank performance and policy impact in China. Studies in Economics and Finance, 42(3), 553–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Q., Zheng, X., & Zhong, N. (2021). Financing for sustainability: Empirical analysis of green bond premium and issuer heterogeneity. Natural Hazards (Dordrecht), 107(3), 2641–2651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, V., Singh, S., & Jain, S. (2024). Green bond premium diagnosis: An interplay of repayment obligation structure. International Review of Economics & Finance, 96, 103689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, T., & Lin, B. (2022). The liquidity impact of Chinese green bonds spreads. International Review of Economics & Finance, 82, 318–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, D. Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Do shareholders benefit from green bonds? Journal of Corporate Finance, 61, 101427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, I., Dias, R., Mo, D., & Tian, X. (2025). When green turns brown: Green premium revisited. Finance Research Letters, 86, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Keppel, T. (2019). Exploring the green premium in corporate green bonds [Master’s thesis, Erasmus School of Economics, Erasmus University Rotterdam]. [Google Scholar]

- Verma, A., & Agarwal, R. (2020, April). A study of green bond market in India: A critical review. In IOP conference series: Materials science and engineering (Vol. 804, No. 1, p. 012052). IOP Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J., Chen, X., Li, X., Yu, J., & Zhong, R. (2020). The market reaction to green bond issuance: Evidence from China. Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, 60, 101294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q., Zhou, Y., Luo, L., & Ji, J. (2019). Research on the factors affecting the risk premium of China’s green bond issuance. Sustainability, 11(22), 6394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wongaree, P., Chiyachantana, C. N., Ding, D. K., Prasarnphanich, P., & Siwasarit, W. (2025). The pricing of green bonds and the determinants of the green bond premium in the Asia-Pacific and European markets. Journal of Open Innovation, 11(2), 100546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y. (2022). Are green bonds priced lower than their conventional peers? Emerging Markets Review, 52, 100909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerbib, O. D. (2019). The effect of pro-environmental preferences on bond prices: Evidence from green bonds. Journal of Banking & Finance, 98, 39–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Step | Method | Process of Review |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Database Selection | Mainstream academic databases (e.g., Web of Science). Open-access academic search engines (e.g., Google Scholar). Professional publishing platforms and journal websites (including Elsevier, Springer, Taylor & Francis Online, and journals with high coverage of green bond research, such as Energy Economics, Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, and Finance Research Letters). High-quality working paper platforms (e.g., SSRN). |

| 2 | Time Period Setting | 2015–2025 |

| 3 | Keyword Identification | The search protocol, 1. “Green Bonds,” 2. “Green Finance,” 3. “Climate Finance,” 4. “Sustainable Development Goals,” and 5. “Greenium”. |

| 4 | Initial Literature Search | N = 300+ |

| 5 | Inclusion Criteria | 1. Studies focusing on the yield or price difference between green bonds and conventional bonds. 2. Providing specific quantitative estimates of the green premium (e.g., spreads expressed in basis points). 3. Using data on bonds issued in the actual market, covering the primary market, secondary market, or both. 4. Clearly stating the data source and empirical methodology. 5. Article types included: published journal articles, high-quality working papers, and policy research reports published by authoritative institutions. |

| 6 | Exclusion Criteria | 1. Literature that did not involve price or yield analysis but instead focused on theoretical analysis (e.g., policy impact, status of green bond development, market structure, etc.). 2. Literature that only provides information such as green bond definitions, ratings, and certification mechanisms, but does not provide premium estimates. 3. Literature with incomplete or untraceable data or methods, or purely theoretical in nature. 4. Literature that focused on other green financial products (e.g., green funds, ESG indices, etc.) rather than green bonds. 5. Non-official publications or articles of lower academic quality (e.g., master’s theses) are excluded. 6. Studies on carbon emission, ESG corporate governance, green finance policy, and case studies, non-Scopus indexed journal. |

| 7 | Screening and Full-Text Review | N = 70 |

| 8 | Final Sample Determination | N = 70 |

| Region | No. Paper |

|---|---|

| Global | 33 |

| U.S. | 10 |

| EU/UK | 10 |

| China | 12 |

| AU/JP/ID | 5 |

| Asia Pacific all | 17 |

| Total | 70 |

| Panel A: Pooled sample | ||

| Spread sign +/− | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| Negative | 65 | −12.44 |

| No premium | 3 | 0 |

| Positive spread | 2 | 3.71 |

| Total no. of paper | 70 | −10.87 |

| Panel B: By region | ||

| Region | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| Global | 33 | −8.03 |

| U.S. | 10 | −5.14 |

| EU/UK | 10 | −14.13 |

| China | 12 | −21.88 |

| AU/JP/ID | 5 | −14.83 |

| Asia Pacific all | 17 | −21.41 |

| Total | 70 |

| Panel A: summary of the database and premium | ||

| Database | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| Bloomberg | 31 | −9.57 |

| Climate Bonds Initiative | 10 | −8.46 |

| Thomson Reuters | 12 | −13.45 |

| CSMAR/WIND | 13 | −21.88 |

| Panel B: Summary of method | ||

| Method | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| PSM | 60 | −10.34 |

| CEM | 3 | −16.21 |

| OLS&DID | 3 | −10.07 |

| Other | 4 | −9.46 |

| Panel A: Market | ||

| Market | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| Primary | 17 | −21.37 |

| Secondary | 25 | −10.36 |

| Combined | 18 | −9.82 |

| Panel B: Sample period | ||

| Period | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| Recent years | 57 | −8.79 |

| 5 years ago (<=2018) | 13 | −14.12 |

| Panel C: Size | ||

| Issue size | No. paper | Spread (Green premium) |

| >500 bonds | 31 | −8.58 |

| <100 bonds | 12 | −20.72 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liu, L.; Hu, Y. Green Bond Pricing: A Comprehensive Review of the Empirical Literature. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120689

Liu L, Hu Y. Green Bond Pricing: A Comprehensive Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(12):689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120689

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Lewis, and Yanqi Hu. 2025. "Green Bond Pricing: A Comprehensive Review of the Empirical Literature" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 12: 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120689

APA StyleLiu, L., & Hu, Y. (2025). Green Bond Pricing: A Comprehensive Review of the Empirical Literature. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(12), 689. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18120689