1. Introduction

Banks provide commercial credit financing only if they believe the borrower can repay it (

Yang et al., 2025). To obtain assurance about repayment, banks generally require commercial loan applicants to submit audited financial statements, especially from applicants in industries or regions in which the banks do not have a large concentration of loans (

Berger et al., 2017). These financial statements serve as inputs to determine the rate of interest, whether the loans are callable, convertibility features, repayment schedules, and collateral requirements (

Shivakumar, 2013). Companies at times restate their financial statements after their initial release. Sometimes these restatements arise from normal operating practices such as mergers and acquisitions, discontinued operations, stock splits, currency issues, and changes in accounting principles (

Flanagan et al., 2008). Other times, restatements result from company errors (unintentional misstatements) or irregularities (intentional misstatements).

Previous studies have examined the effect of restatements on lending decisions (e.g.,

Graham et al., 2008;

Files & Gurun, 2018). One such study by

Schneider (

2025) involved a behavioral experiment and found that restatements do affect lending decisions. Additionally, restatements caused by irregularities have a greater adverse impact than restatements caused by errors, and restatements prompted by auditors have a greater adverse impact than restatements prompted by company management. The current study extends

Schneider (

2025) by conducting a similar experiment to address whether restatements involving revenues have a different impact on lending decisions than restatements involving expenses and whether restatements that result in increased net income impact lending decisions differently than restatements that result in decreased net income. These differential effects can be explained by signaling theory (e.g.,

Connelly et al., 2025;

Arhinful et al., 2025).

Signaling theory describes how one entity, which possesses information, communicates that information through signals to another entity that does not have that information. Because revenue recognition is considered by many to be the most important specific individual accounting issue for both users and preparers of financial reporting (

Demirkan & Fuerman, 2014), and because companies tend to manage earnings mostly through manipulating revenue recognition (

Park & Wu, 2009), restatements that are caused by improper revenue recognition may send a signal that these misstatements are more intentional than misstatements involving expenses. Likewise, restatements that decrease reported profits are considered to be more severe than those that increase profits (

Files & Gurun, 2018). Hence, a decrease in net income, more so than an increase in net income would, send a signal that company management has attempted to manipulate the reported earnings.

The experiment in this study involved the participation of 64 commercial lenders, who were given information about a hypothetical borrower. Participants assessed the risk associated with the loan applicant as well as the likelihood of credit approval. This study did not find statistically significant differences, at the current sample size, for risk assessments or probabilities of granting credit, between restatements caused by revenue misstatements versus restatements caused by misstatements of expenses. Additionally, no statistically significant differences were found at the current sample size, for risk assessments or probabilities of granting credit, between income-decreasing restatements and those involving income-increasing restatements. These results can be explained by lenders’ perceptions that restatements are not very influential in making lending decisions. At the end of the experiment, the lenders rated “whether there has been a restatement” as the least important factor in a list of seven items that might affect lending decisions. If lenders do not care much about restatements, it follows that it does not matter whether the restatements involve revenues or expenses, or whether they increase or decrease profits.

2. Previous Studies on Restatements

Prior studies have investigated financial statement restatements in the context of restating firms’ stock prices (e.g.,

Alfonso et al., 2018), turnover of executives and board members at restating firms (e.g.,

Burks, 2010), various audit issues at restating firms (e.g.,

Feldmann et al., 2009), earnings forecasts in post-restatement periods (e.g.,

Palmrose et al., 2004), and financial reporting conservatism in post-restatement periods (e.g.,

Moore & Pfeiffer, 2009).

Some studies have examined how restatement disclosures have influenced commercial lending.

Graham et al. (

2008) demonstrate that compared with loans initiated before a restatement, loans that are initiated after a restatement have higher spreads, shorter maturities, a greater likelihood of being secured, and more covenant restrictions.

Baber et al. (

2013) find that restatements increase the cost of municipal debt financing and this increase is larger when municipal governance is poor. Following restatements, municipalities tend to decrease the use of debt financing and are more likely to issue secured rather than unsecured debt.

Files and Gurun (

2018) show that restatements by peer firms in the same industry increase a borrower’s loan spread and that this increase occurs regardless of restatement severity. They also find increases in loan spreads following customer restatements, but only when the restatements are relatively severe.

In a behavioral experiment,

Schneider (

2023) finds an adverse impact on lending decisions when a borrower’s audit firm has had past associations with borrowers who have defaulted, have disclosed financial statement restatements, or have experienced regulatory enforcement actions. While that study examines how knowledge about an auditor’s past associations with restatements affects lending decisions,

Schneider (

2025) focuses on the effects of restatements themselves on lending decisions and finds that restatement disclosures have an adverse impact. Furthermore, restatements caused by irregularities have a greater adverse impact than those caused by errors, and restatements initiated by auditors have a greater adverse impact than those initiated by company management. The current study extends

Schneider (

2025) by conducting a similar experiment to address whether restatements involving revenues have a differential impact on lending decisions than restatements involving expenses and whether restatements that yield a net income increase impact lending decisions differently than restatements that yield a net income reduction.

2.1. Studies Involving Revenues and Expenses

A number of studies have examined issues relating to restatements resulting from misstatements of revenues and misstatements involving expenses.

Hribar and Jenkins (

2004) find that in their sample of restatement firms, revenue recognition issues accounted for the most frequent cause of restatements (40.4%). Likewise,

Desai et al. (

2006) report that restatements resulting from improper revenue recognition are the most common cause for restatements and also generate the largest negative stock market reactions.

Gleason et al. (

2008) find that restatements which negatively impact shareholder wealth at the restating firm also induce share price reductions among non-restating companies in the same industry. The share price decline is larger for peer companies having high industry-adjusted accruals. This accounting contagion is concentrated among revenue restatements by relatively large companies in the industry.

Findings from

Wilson (

2008) indicate a decline in the information content of earnings following restatements, but it is short-lived, lasting only three quarters after restatement disclosures. Moreover, this decline is longer lasting for companies that issue restatements to correct revenue recognition problems relative to other reasons for restatements.

Park and Wu (

2009) analyze traded syndicated loans to see how the secondary loan market reacts to restatements and they find an increased cost of syndicated bank loans after restatements. This negative loan market reaction is more severe when the primary reason for restatement is related to revenue recognition issues.

Demirkan and Fuerman (

2014) show that restatements involving revenues, far more than any other types of restatements, are associated with auditors being named defendants in lawsuits and also auditors experiencing more severe, negative outcomes from litigation.

2.2. Studies Involving Income-Increasing vs. Income-Decreasing Restatements

Some studies have examined restatements by analyzing issues relating to whether the initially reported net income was understated or overstated.

Graham et al. (

2008) reported that for their restatement sample, earnings overstatements outnumbered earnings understatements by 9 to 1.

DeFond and Jiambalvo (

1991) indicate that earnings overstatements are more likely when firms have diffused ownership, lower growth in earnings, and fewer income-increasing GAAP alternatives available. On the other hand, overstatements are less likely when firms have audit committees.

Srinivasan (

2005) finds a much higher propensity for restating firms to decrease reported net income (79% of the sample) than to increase net income (21%). Penalties are strongest for outside directors of the income-decreasing companies.

Palmrose et al. (

2004) find that more negative stock market returns are associated with restatements that decrease reported income.

Callen et al. (

2006) show that market reactions to restatements due to errors are generally negative, but market reactions to announcements of income-increasing restatements due to errors are not statistically different from zero.

Analyzing restatements due to errors,

Thompson and McCoy (

2008) demonstrate that companies reporting income-decreasing restatements were more likely to change auditors than companies with restatements whose errors did not decrease income. Consistent with this finding,

Huang and Scholz (

2012) show that restating companies are more likely to experience auditor resignations than non-restating companies and that the likelihood of resignation increases when restatements reverse a previously reported positive net income to a negative net income. These results are also corroborated by

Mande and Son (

2013), who find that the more negative the effect of a restatement on net income, the higher the frequency of an auditor switch in the following year.

Drake et al. (

2015) demonstrate that when restatements are announced, abnormal short selling is significantly higher than is typical. Short sellers tend to target small companies, whose information environments may be weaker, as well as companies making restatements that reduce previously reported net income.

Cahan et al. (

2024) examine the effects of restatements on shareholdings and find that institutional investors that have a higher level of societal trust reduce their shareholdings in restating firms to a greater degree than do institutional investors that have a lower level of societal trust. Furthermore, societal trust has a greater impact on post-restatement divestment when the restatement has decreased the firm’s net income.

3. Hypotheses

Financial statement users tend to focus more on the revenues than on expenses when analyzing earnings (e.g.,

Ertimur et al., 2003) and revenue recognition is “likely the most important, specific individual accounting issue for both users and preparers of financial reporting” (

Demirkan & Fuerman, 2014, p. 166). Thus, it can be inferred that misstatements involving revenues would be viewed as more serious than misstatements involving expenses. Furthermore, companies tend to manage earnings mostly through manipulating revenue recognition, so revenue recognition misstatements may be perceived to be more intentional than other restatement items (

Park & Wu, 2009).

Prior research on restatement disclosures also suggests that restatements arising from revenue misstatements appear to be more severe than those arising from misstatements of expenses. Studies reviewed above indicate that, relative to expense-induced restatements, revenue-induced restatements generate larger negative stock price reactions (

Desai et al., 2006;

Gleason et al., 2008), longer lasing declines in the information content of earnings following restatements (

Wilson, 2008), more adverse loan market reactions (

Park & Wu, 2009), and auditors more often named defendants in lawsuits and experiencing more severe, negative outcomes from litigation (

Demirkan & Fuerman, 2014). These arguments and prior research evidence lead to the following hypotheses:

H1a: Risk assessments will be higher for borrowers that have had restatements resulting from misstatements of revenues as compared to borrowers that have had restatements resulting from misstatements of expenses.

H1b: Probabilities of credit approval will be lower for borrowers that have had restatements resulting from misstatements of revenues as compared to borrowers that have had restatements resulting from misstatements of expenses.

Restatements that decrease the reported net income are considered to be more severe than those that increase net income (

Files & Gurun, 2018). A decrease in net income might be perceived as an attempt by company management to initially inflate the reported earnings so as to make the company appear more attractive. This would reflect negatively on company management’s credibility and, in turn, may lead to reluctance by loan officers to grant credit.

Prior research appears to support this notion that income-deceasing restatements are perceived as more severe than income-increasing restatements. The studies reviewed earlier suggest that, relative to restatements than increase income, restatements that decrease income yield more negative stock market returns (

Palmrose et al., 2004), stronger penalties for outside directors (

Srinivasan, 2005), greater likelihood of auditor switches (

Mande & Son, 2013;

Huang & Scholz, 2012;

Thompson & McCoy, 2008), more short selling behavior (

Drake et al., 2015), and a greater impact of societal trust on post-restatement divestment (

Cahan et al., 2024). Based on the above arguments and prior research, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a: Risk assessments will be higher for borrowers that have had restatements which result in decreased net income as compared to borrowers that have had restatements which result in increased net income.

H2b: Probabilities of credit approval will be lower for borrowers that have had restatements which result in decreased net income as compared to borrowers that have had restatements which result in increased net income.

4. Experimental Design and Task

The experimental design is 2 × 2 between subjects, where the independent variables are the items requiring restatement (revenues vs. expenses) and whether the restatement resulted in increased or decreased net income. The Revenues/Increase (RI) version portrays a restatement caused by improper revenue recognition that results in an increased amount of reported net income in the restated income statement. A Revenues/Decrease (RD) version involves a restatement caused by improper revenue recognition and resulting in a decreased amount of reported net income. An Expenses/Increase (EI) version portrays a restatement caused by an incorrect amount of expenses which results in an increased amount of reported net income. A fourth version, Expenses/Decrease (ED), presents a restatement caused by an incorrect amount of expenses that results in a decreased amount of reported net income. All participants were informed that the restatements resulted from unintentional errors and that the restatements were initiated by company management.

Each of the four questionnaire versions described the same case scenario which involved a commercial lending decision pertaining to a hypothetical company applying for a loan. The case provided background information about the applicant and its financial statements for recent years. The case also stated that the company’s financial statements had been audited and that the audit firm had issued a clean (i.e., unqualified) opinion.

The participants first assessed the level of risk, on a 10-point scale from very low risk to very high risk, associated with extending a four-million-dollar line of credit to the loan applicant. The loan officers then were asked to determine the probability that they would grant the four-million-dollar line of credit to the loan applicant at a reasonable rate of interest as determined by their bank. Next, the lenders rated the importance of various factors in making these lending decisions. Finally, they answered several questions involving demographic and other issues.

5. Participant Demographics

Commercial lenders located in several U.S. states were contacted by phone and asked whether they would be willing to complete a questionnaire for a study dealing with financial reporting and commercial lending. Two hundred ninety questionnaires were sent to loan officers who agreed to consider participation in the study.

A total of 64 loan officers from 47 different financial institutions participated in the study, resulting in a response rate of 22 percent. The lenders average 21.6 years of experience as loan officers, have a mean age of 51.5 years, 47.6 percent possess a masters degree or higher, and 95.2 percent are male. Close to half (46 percent) of the participants revealed that the banks they work for have more than one billion dollars in assets. A majority of the lenders (50.8 percent) indicated that they have sole loan approval authority up to a certain dollar limit, while 23.8 percent have joint authority with others, 1.6 percent have sole authority, and 23.8 percent have other arrangements (e.g., serve on a loan committee). The distribution of participants into this study’s four groups appears in

Table 1. Statistical tests reveal no significant differences for five of six demographic variables among the four groups. Only educational level yielded a marginally significant difference between the ED and RI groups.

6. Results

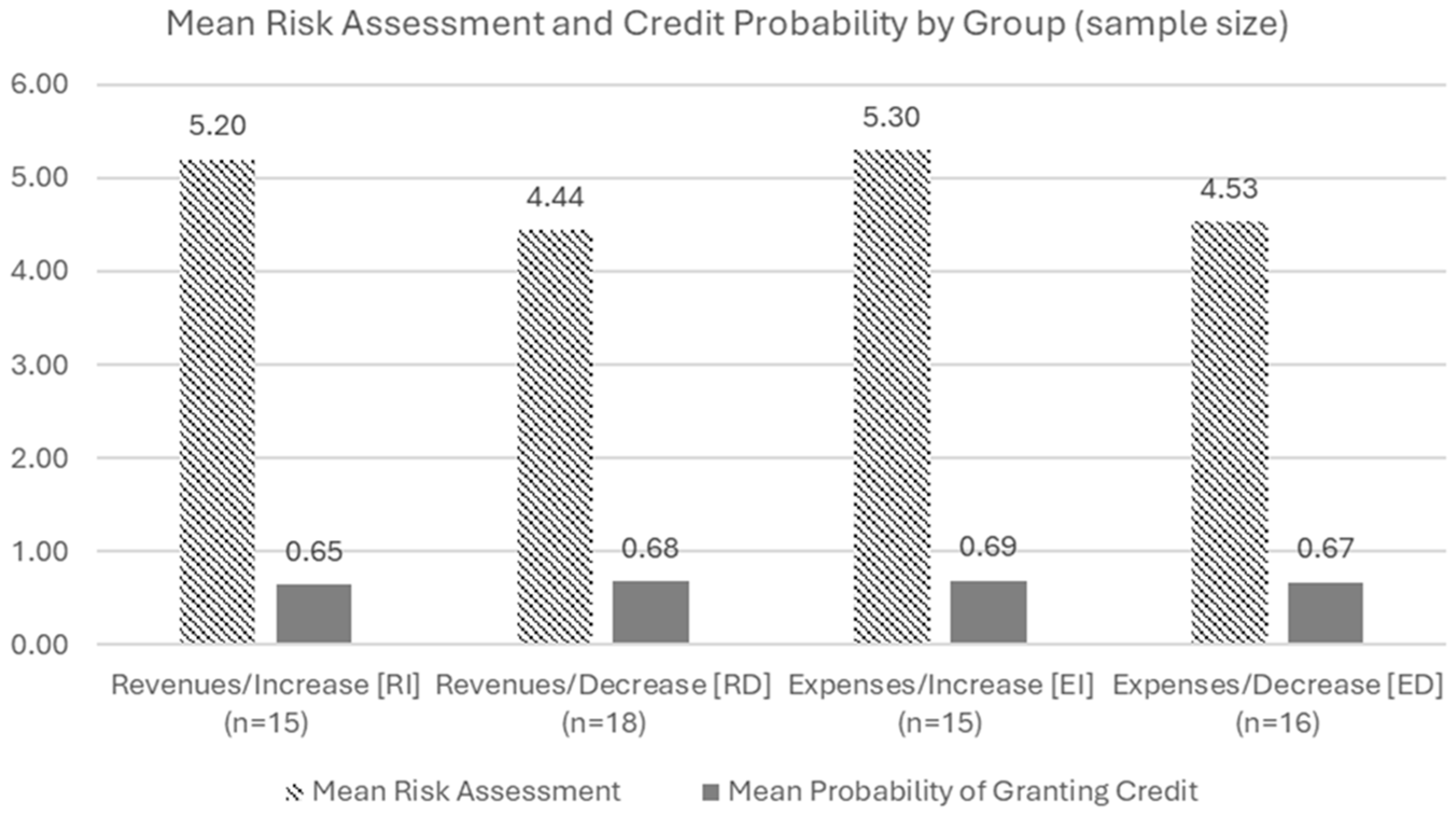

Table 1 displays the average responses to risk assessments and probabilities of credit approval for each version of the questionnaire. These averages are also shown in graphical form in

Figure 1. The overall average risk assessment (1 = very low risk; 10 = very high risk) is 4.84, ranging from 4.44 for the RD group to 5.30 for the EI group. The average probability of credit approval is 0.67, and the range is from 0.65 for the RI group to 0.69 for the EI group.

The first set of hypotheses examines the effects of restatements involving revenue misstatements versus restatements involving misstatements of expenses. The average risk assessment for the combined Revenues groups is 4.79 and that of the combined Expenses groups is 4.90. The average probability of credit approval for the combined Revenues groups is 0.67 and the average for the combined Expenses groups is 0.68. While the mean probabilities for granting the line of credit are in the hypothesized direction, the mean risk assessments are not in the hypothesized direction.

The second set of hypotheses investigates the effects of income-increasing restatements versus income-decreasing restatements. The average risk assessment for the combined Increase groups is 5.25 and that of the combined Decrease groups is 4.49. The average probability of credit approval for the combined Increase groups is 0.67 and the average for the combined Decrease groups is 0.68. Neither the averages for risk assessment nor the averages for the probability of credit approval are in the directions that were hypothesized.

To test these two sets of hypotheses, a MANOVA is performed first. The differences are not statistically significant for the income statement item, i.e., restatements involving revenues versus restatements involving expenses (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.996; p = 0.898) or whether the restatement increased or decreased the reported net income (Wilks’ Lambda = 0.927; p = 0.103).

Next, a 2 × 2 ANOVA is performed with risk assessment as the dependent variable and the results are shown in Panel A of

Table 2. The differences are not statistically significant for the income statement item (F = 0.053;

p = 0.819) nor for whether the restatement increased or decreased the reported net income (F = 2.302;

p = 0.134). An ANCOVA test with six demographic variables as covariates revealed similar results.

Another 2 × 2 ANOVA is performed with probability of granting the line of credit as the dependent variable and the results are shown in Panel B of

Table 2. The differences are not statistically significant for the income statement item (F = 0.020;

p = 0.888) nor for whether the restatement increased or decreased the reported net income (F = 0.010;

p = 0.922). Additionally, an ANCOVA test with six demographic variables as covariates produced similar results.

Additionally, ANCOVA tests for each of the two dependent variables were conducted with six demographic variables as covariates. The demographic variables are participants’ age, sex, years of lending experience, educational level, bank size, and loan approval authority. The ANCOVA tests produced similar results as the MANOVA and ANOVA tests. None of the demographic variables affected the responses.

Neither the MANOVA, ANOVA, nor ANCOVA tests support any of the hypotheses. Hence, there is insufficient evidence to conclude that restatements caused by revenue misstatements produce assessments of risk or probabilities of credit approval that are different from restatements caused by misstatements of expenses. Additionally, the results do not enable one to conclude that income-decreasing restatements yield risk assessments or probabilities of granting credit that are different from income-increasing restatements.

After responding to the two dependent variables, the lenders also rated the importance of seven factors in making their risk assessments and credit granting decisions (1 = no importance; 10 = very important). These ratings are displayed in

Table 3. The most important were “balance sheet”, followed by “income statement”, and then followed by “statement of cash flows”. The ratings for all seven factors with the exception of “whether financial statements have been restated” differ significantly from the scale midpoint of 5.5. In fact, this factor was rated least important of all seven. This may help explain the findings above that neither the income statement item (revenues or expenses) nor the directionality of the restatement (income-increasing or income-decreasing) impacts lending judgments differently. Since the existence of a restatement does not matter a great deal to lenders, then characteristics of restatements such as which income statement item is restated or the directionality of the restatement would not be expected to influence lenders judgments.

7. Concluding Remarks

This study did not find statistically significant differences, at the current sample size, for assessments of risk or probabilities of credit approval, between restatements caused by revenue misstatements versus restatements caused by misstatements of expenses. In addition, no statistically significant differences were found at the current sample size, for risk assessments or probabilities of credit approval, between income-decreasing restatements and those involving income-increasing restatements. These results can be explained by lenders’ perceptions that restatements are not very influential in making lending decisions (as implied by their rating, at the end of the experiment, of “whether there has been a restatement” as the least important factor in a list of seven items that might affect lending decisions). If lenders do not care much about restatements, it follows that it does not matter whether the restatements involve revenues or expenses, or whether they increase or decrease profits. These findings do not align with the signaling theory that served as the basis for the two sets of hypotheses. Signaling theory, which appears to reasonably explain investors’ actions in the capital market, may not apply in the same way to bank lenders. It may be that lenders have access to different information sources (internal information, relationship lending, collateral), they may have a different information hierarchy as they focus more on financial statement information (as shown in

Table 3), or they may use different cognitive models for risk assessment.

An implication is that when restatements are due to unintentional errors and initiated by company management, borrowers may not need to be more concerned that their restated financial statements involve revenue items rather than expense items or that they decrease profits as opposed to increase profits. As to implications for lenders, the null findings may indicate a general insensitivity among lenders to restatement details, or they may reflect contextual constraints of the experimental task. Perhaps lenders would react differently to restatements caused by irregularities or restatements initiated by outside auditors. Perhaps also lending decisions would be different for a larger or more risky loan applicant than was portrayed in this study. An implication for regulators is that they may not need to mandate detailed disclosures about the revenue or expense items that necessitated the restatement. An implication for outside auditors is that while they may wish to scrutinize revenue recognition more closely than expenses because the former has been found to be the cause of restatements more often than the latter, the level of scrutiny may not need to be further influenced by concern about lenders’ perceptions about revenue-related versus expense-related misstatements.

This research extends that of

Schneider (

2025), who finds that restatement disclosures have an adverse impact on lending decisions, that restatements caused by irregularities (i.e., intentional misstatements) have a greater adverse impact than those caused by errors (i.e., unintentional misstatements), and that restatements initiated by auditors have a greater adverse impact than those initiated by company management So, while the intentionality of the restatement and the party that initiated the restatement appear to influence lending decisions, this study did not find evidence that the type of income statement item involved or the directionality of the restated net income matters to lenders. The seemingly inconsistent findings between the current study and

Schneider (

2025) might be due to the different information provided to lenders—namely, the current study involved a different type of collateral, restatements in the current study resulted from unintentional errors only, whereas restatements in

Schneider (

2025) were due to errors or irregularities, and in the current study, restatements were initiated by company management, whereas in

Schneider (

2025), they were initiated by either company management or outside auditors. The current study’s results may also be viewed as inconsistent with those of

Graham et al. (

2008), who demonstrate that restatements influence lending conditions such as loan spreads, covenants, and maturities. An alternative explanation is that perhaps restatements influence the terms of the loan, but not the initial decision of whether to approve the loan.

There are potential limitations to the results of this study. Usually, commercial loan officers obtain more information about a loan applicant than they received in this study’s questionnaire (e.g., borrower reputation, relationship history). A second limitation is that this study used a single borrowing company and so the results might not be generalizable to other types of borrowing companies. The scenario involved a loan of $4 million, a specific industry, and a specific financial condition for the borrower. Therefore, the results may only apply to this exact case. With a larger or smaller loan, in a different industry, or if the company were in worse condition, lenders might pay more attention to restatements. Future studies should therefore examine the effects of restatements on lending decisions using loan applicant scenarios with different characteristics relating to loan size, company size, industry, competitive environment, and financial condition. Third, the participants were informed that the restatements resulted from unintentional errors and that the restatements were initiated by company management. Perhaps different results would have been obtained in a scenario where the restatements were caused by irregularities/fraud or where the restatements were prompted by the company’s outside auditors. Future research can address these issues. Fourth, economic consequences such as suffering losses from lending decisions were not a feature in this study’s experiment. Participants did not have any personal or institutional funds at risk in this experiment nor was their reputation at risk. This absence of monetary or reputational risk may have weakened their engagement and realism in decision-making, leading to attenuated treatment effects. Rather than eliciting loan officer’s intentions, future studies may wish to focus on lending decisions in experimental market settings where compensation to participants would be arrived at by assessing the quality of their lending decisions. Another consideration is that nearly 95% of participants in this study are male and most have over 20 years of lending experience. This demographic homogeneity could limit insight into how gender or experience diversity might influence restatement interpretation and lending decisions. This study’s results may also be taken with caution due to its relatively small sample size. The lack of significant differences obtained may have resulted from insufficient power. Finally, the study did not use a recall check to determine whether participants remembered which specific independent variable manipulation they received.