Regulating Green Finance and Managing Environmental Risks in the Conditions of Global Uncertainty

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Review

2.1. Mechanisms

- −

- ESG investments, which are investments made during the manifestations of environmental (E) and social (S) responsibility, and also under the condition of the high quality of corporate governance (G) (Bhatia et al., 2025; J. Liu & Liang, 2025);

- −

- Green finance, which is financial resources aimed at environmental protection and the fight against climate change (B. Li et al., 2025; Shi & Yang, 2025);

- −

- Greenwashing, which is the practice of unfair advertising in which companies provide false information about their green initiatives and environmental parameters of their economic activities (Inderst & Opp, 2025; L. Wang et al., 2025).

2.2. Regulatory Framework

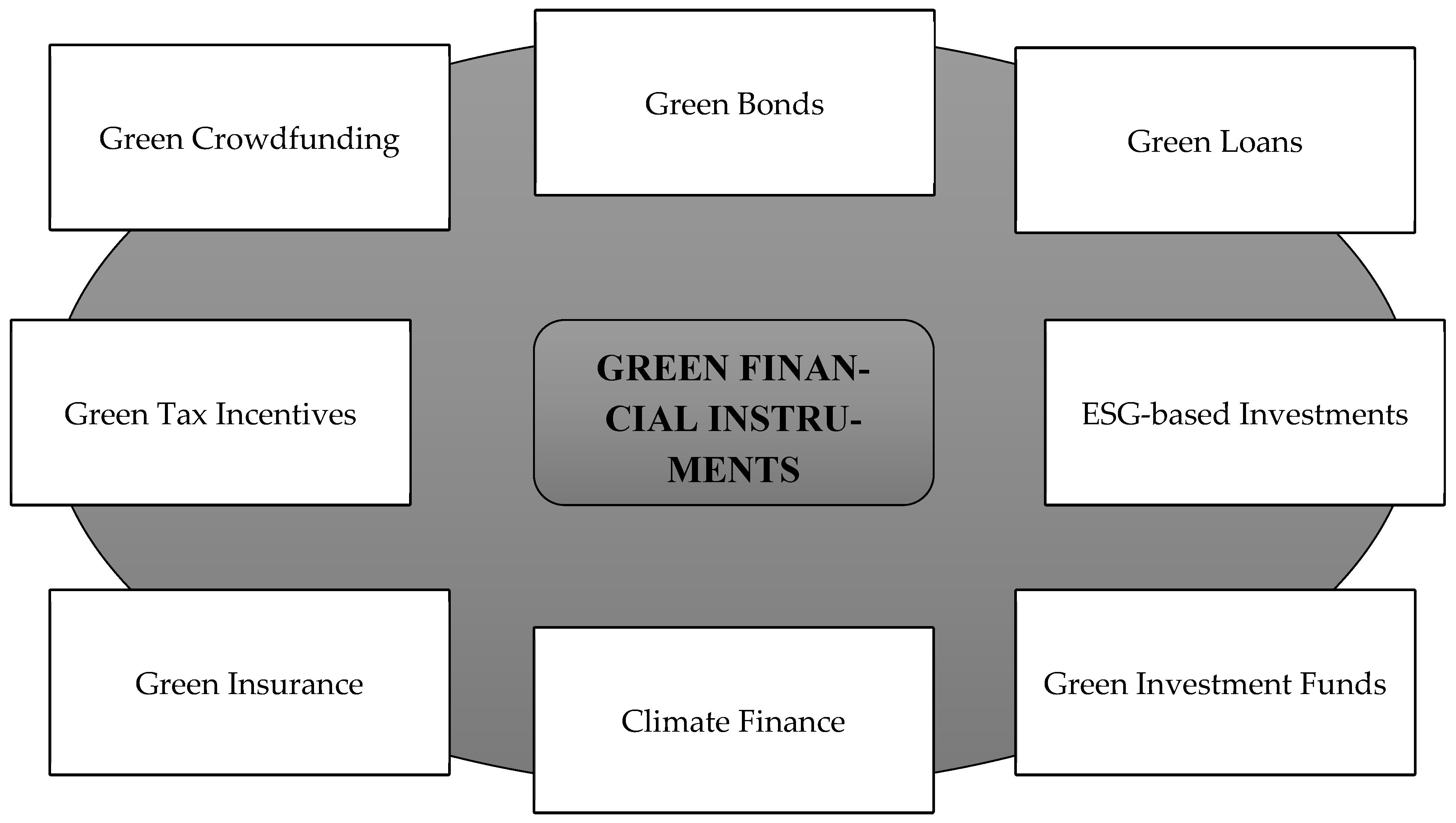

2.3. Classification and Conceptual Framework of Green Financial Tools

2.4. Empirical Results

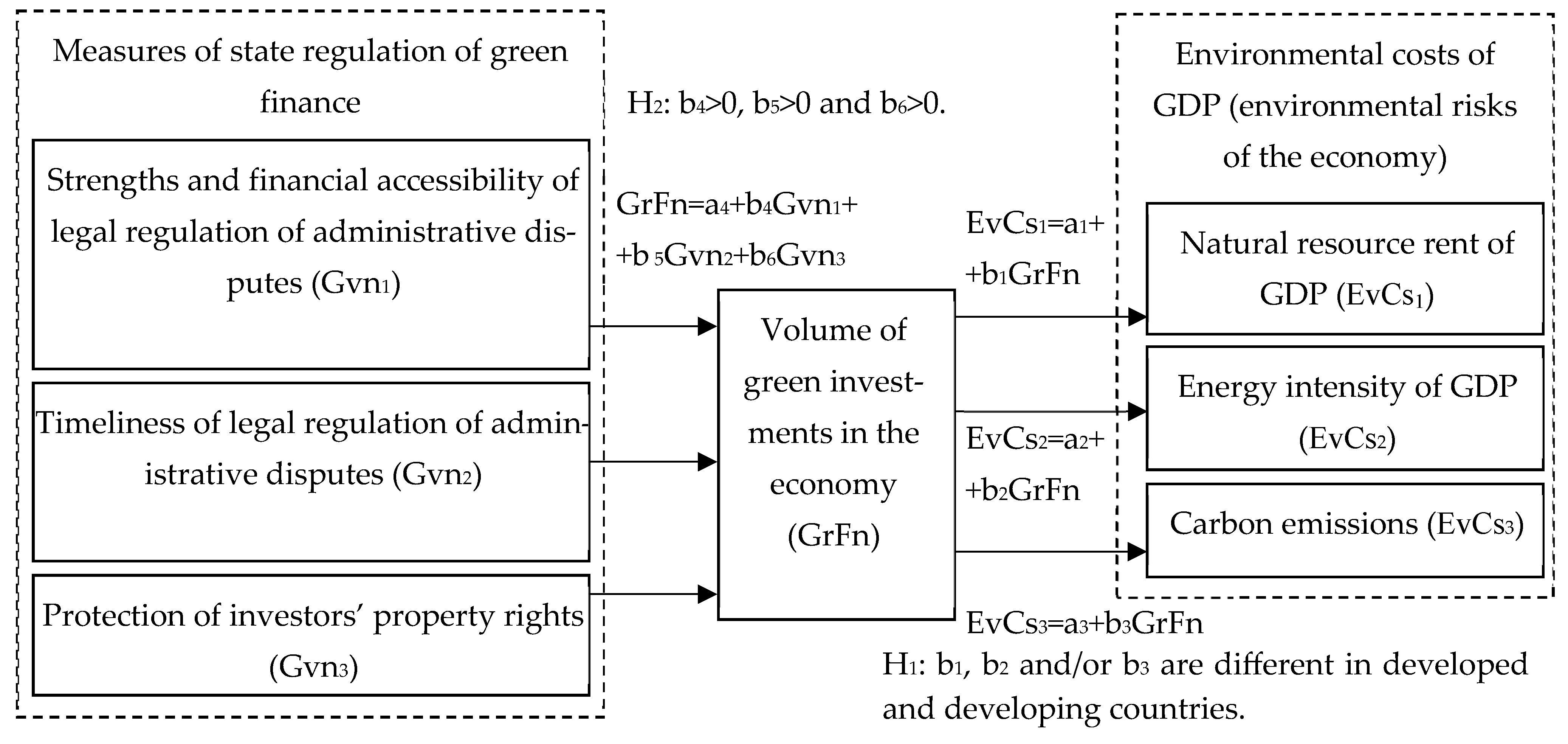

3. Materials and Methods

- −

- Environmental costs of GDP—natural resources rent (EvCs1 according to the statistics by the World Bank, 2025c), energy intensity (EvCs2 according to the statistics by the World Bank, 2025b), and carbon intensity (EvCs3 according to the statistics by the World Bank, 2025c) based on the data from Table 2—on the activity of green investment in the economy (GrFn according to the statistics by the Global Green Growth Institute (2025) based on the data from Table 1);

- −

- Activity of green investment in the economy (GrFn) on the factors of state regulation of green finance—strength and financial affordability of legal regulation of administrative disputes (Gvn1), its timeliness (Gvn2), and protection of investors’ property rights (Gvn3), according to the statistics by the UN (2025) based on the data from Table 3.

EvCs2 = a2 + b2GrFn,

EvCs3 = a3 + b3GrFn,

GrFn = a4 + b4Gvn1 + b 5Gvn2 + b6Gvn3.

4. Results

4.1. General Results

EvCs2 = −19.1298 + 0.5021GrFn,

EvCs3 = 0.0521 + 0.0014GrFn (F-test was not passed),

GrFn = 55.6649 + 14.1786Gvn1 + 1.7871Gvn2 + 0.9720Gvn3 (F-test was not passed).

EvCs2 = 17.3772 − 0.1204GrFn,

EvCs3 = −0.0045 + 0.0045GrFn,

GrFn = 42.1262 + 3.4105Gvn1 + 26.5479Gvn2 + 12.3471Gvn3.

4.2. Multicollinearity Test

4.3. Differences Between Developed and Developing Countries

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

- In developed countries, the growth of the activity of green investing in the economy leads to the reduction in almost all environmental costs of GDP: it ensures the reduction in natural resources rents and an increase in GDP per unit of energy use, but does not have a statistically significant effect on the carbon intensity of GDP.

- Unlike developed countries, in developing countries, growth of the activity of green investing in the economy leads to an increase in almost all environmental costs of GDP, i.e., systemic growth of environmental risks: an increase in total natural resources rents, a decline in GDP per unit of energy use, and growth of carbon intensity of GDP.

- Unlike developed countries, in which green investments are not determined by the influence of the factors of state regulation, the implementation of the measures of state regulation of green finance—improvement of strength and financial accessibility of legal regulation of administrative disputes, an increase in timeliness of legal regulation of these disputes, and an increase in protection of investors’ property rights—in developing countries ensures an inflow of green investments in the economy.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al-Rawashdeh, F., Alnawaiseh, M. B., Al-Faouri, E. H., Altarawneh, R. M., Alsheyyab, Y., & Mirzaliev, S. (2025). Steps toward achieving sustainable development goals: The role of carbon finance, green social behaviour and awareness, energy transition, and government governance in E7 countries. International Journal of Energy Economics and Policy, 15(3), 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- APEC Energy Working Group. (2018). Promoting innovative green financing mechanisms for sustainable and quality infrastructure development in the APEC region. Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation. Available online: https://www.apec.org/docs/default-source/Publications/2018/9/Promoting-Green-Financing-Mechanisms/218_EWG_Promoting-Green-Financing-Mechanisms.pdf (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Azimi, M. N., Raham, M. M., & Maraseni, T. (2025). Green trade, governance, finance, and energy efficiency: Shaping environmental landscape in global powerhouses. Journal of Environmental Management, 385, 125674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatia, R., Kadyan, S., Bhasin, N. K., Singh, S., & Bathla, S. (2025). Redefining investment paradigms: ESG integration and sustainable finance in new era of investing. In Global business transformation innovation technology and sustainability (pp. 31–46). CRC Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatnagar, S., & Sharma, D. (2022). Evolution of green finance and its enablers: A bibliometric analysis. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 162, 112405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemmanur, T. J., Cheng, B., Wang, Z.-T., & Yu, Q. (2025). State ownership, environmental regulation, and corporate green investment: Evidence from China’s 2015 environmental protection law changes. Journal of Business Ethics, 200(2), 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climate Bonds Initiative. (n.d.). Markets: Explaining green bonds. Available online: https://www.climatebonds.net/news-events/blog/climate-bonds-releases-updated-green-bonds-methodolog (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Dziwok, E., & Jäger, J. (2021). A classification of different approaches to green finance and green monetary policy. Sustainability, 13(21), 11902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Environmental Finance Data. (2025). Loans market growth. Available online: https://efdata.org/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Ergasheva, S. T., Zinovyeva, I. S., Abdurashitov, A. A., Kopytina, Y. A., & Makarova, T. V. (2023). ESG investments in support of the development of the green economy in Russia and central Asia. In Environmental footprints and eco-design of products and processes (pp. 419–428). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, W., Bilivogui, P., Wu, J., & Mu, X. (2023). Green finance: Current status, development, and future course of actions in China. Environmental Research Communications, 5(4), 045010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flammer, C. (2021). Corporate green bonds. Journal of Financial Economics, 142(2), 499–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C., Lu, L., & Pirabi, M. (2023). Advancing green finance: A review of sustainable development. DESD, 1, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilchrist, D., Yu, J., & Zhong, R. (2021). The limits of green finance: A survey of literature in the context of green bonds and green loans. Sustainability, 13(2), 478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Green Growth Institute. (2025). Green growth index: Simulation tool. Available online: https://ggindex-simtool.gggi.org/SimulationDashBoard/country-profile (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Global Market Statistics. (2025). Green insurance market insights|2025–2033. Available online: https://www.globalmarketstatistics.com/market-reports/green-insurance-market-13863 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Guo, M., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Identifying the nexus among green investment, economic restructuring and carbon emission: Evidence from provinces in China. Sustainable Futures, 10, 101058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inderst, R., & Opp, M. M. (2025). Sustainable finance versus environmental policy: Does greenwashing justify a taxonomy for sustainable investments? Journal of Financial Economics, 163, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. (2022). Climate change 2022: Impacts, adaptation and vulnerability. Contribution of working group ii to the sixth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change. Cambridge University Press. Available online: https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar6/wg2/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Irwin-Hunt, A. (2025). The 2024 investment matrix. fDi intelligence. Available online: https://www.fdiintelligence.com/content/9d6e552e-f390-5d39-b42c-507feda69446 (accessed on 3 May 2025).

- Kang, X., Zhang, J., Ren, W., & Shi, J. (2025). Green investment, environmental regulation, and environmental performance. Finance Research Letters, 80, 107383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kantor, O. G., Rudneva, Y. R., Dunov, D. Y., Ergasheva, S. T., & Leybert, B. M. (2023). Green finance: Analysis of prospects of the Russian market food security in the economy of the future: Transition from digital agriculture to agriculture 4.0 based on deep learning (pp. 45–56). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, B., Wang, X., Khurshid, A., & Saleem, S. F. (2025). Environmental governance, green finance, and mitigation technologies: Pathways to carbon neutrality in European industrial economies. International Journal of Environmental Science and Technology. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H., Yu, Z., Chen, G., & Nie, Y. (2025). Research on the impact of green finance on regional carbon emission reduction and its role mechanisms. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 17293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, C., Cui, P., Zhao, H., Zhang, Z., Zhu, Y., & Liu, H. (2024). Green finance, economic policy uncertainty, and corporate ESG performance. Sustainability, 16(22), 10141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J., & Liang, G. (2025). Green finance, green governance performance, and the ESG performance: Evidence from a quasi-natural experiment. Finance Research Letters, 84, 107785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K., Han, D., Li, C., & Chen, Y. (2025). Research on the impact of green finance on collaborative governance of pollution reduction and carbon reduction. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 13394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Market Research Future. (2025). Global crowdfunding market overview. Available online: https://www.marketresearchfuture.com/reports/crowdfunding-market-22857 (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Morgan Stanley Institute for Sustainable Investing. (2025). Sustainable fund returns lag peers’ in second half of 2024. Available online: https://www.morganstanley.com/insights/articles/sustainable-funds-performance-second-half-2024 (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Morningstar. (2025). Global sustainable fund flows: Q1 2025 in review. Available online: https://www.morningstar.com/business/insights/research/global-esg-flows (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Muchiri, M. K., Erdei-Gally, S., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2025). Nexus between green financing and carbon emissions: Does increased environmental expenditure enhance the effectiveness of green finance in reducing carbon emissions? Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(2), 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naran, B., Buchner, B., Price, M., Stout, S., Taylor, M., & Zabeida, D. (2024). Global landscape of climate finance 2024. Climate policy initiative. Available online: https://www.climatepolicyinitiative.org/publication/global-landscape-of-climate-finance-2024/ (accessed on 6 May 2025).

- Nedopil, C., Dordi, T., & Weber, O. (2021). The nature of global green finance standards—Evolution, differences, and three models. Sustainability, 13(7), 3723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OPEC Fund. (2025). Climate finance. Report 2024. Climate action in addressing development challenge. Available online: https://publications.opecfund.org/view/733688099/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Pangarkar, T. (2024). Green finance market surges towards USD 22,754 bn by 2033. Market.us Scoop. Available online: https://scoop.market.us/green-finance-market-news/ (accessed on 5 May 2025).

- Shi, Y., & Yang, B. (2025). Green finance instruments and empowering sustainability in East Asian economies. Humanities and Social Sciences Communications, 12(1), 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susan, E. B., & Pan, Y. (2024). Trust as a determinant of green finance through information sharing and technological penetration: Integrating the moderation of governance for sustainable growth. Technology in Society, 77, 102565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, H., Zhuang, S., Xue, R., Cao, W., Tian, J., & Shan, Y. (2022). Environmental finance: An interdisciplinary review. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 179, 121639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavares, F. B. R., Collaço, F. M. d. A., & Oliveira, M. C. (2024). instrumentos financeiros verdes e o atingimento dos objetivos de desenvolvimento sustentável nos países em desenvolvimento: Uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Boletim de Conjuntura (BOCA), 17, 433–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twidale, S. (2024a). Global carbon emissions pricing raised record $104 bln in 2023. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/global-carbon-emissions-pricing-raised-record-104-bln-2023-2024-05-21/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- Twidale, S. (2024b). Global carbon markets value hit record $949 bln last year—LSEG. Reuters. Available online: https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/global-carbon-markets-value-hit-record-949-bln-last-year-lseg-2024-02-12/ (accessed on 4 May 2025).

- UN. (2025). Sustainable development goals report 2025. Available online: https://unstats.un.org/sdgs/report/2025/The-Sustainable-Development-Goals-Report-2025.pdf (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- Verified Market Research. (2025). Green insurance market size and forecast. Available online: https://www.verifiedmarketresearch.com/product/green-insurance-market/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Wang, L., Tang, R., & Zhou, X. (2025). Financial crime risks in environmental, social, and governance (ESG) investment: Perspectives on greenwashing and false disclosure. Finance Research Letters, 85, 107856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z., He, A., & Nan, S. (2025). Green finance reform, multifaceted collaborative governance, and corporate greenwashing: Evidence from double/debiased machine learning method. Journal of Environmental Management, 383, 125466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2025a). Carbon intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP $ of GDP). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.GHG.CO2.RT.GDP.PP.KD?view=chart (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- World Bank. (2025b). GDP per unit of energy use (constant 2021 PPP $ per kg of oil equivalent). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EG.GDP.PUSE.KO.PP.KD?view=chart (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- World Bank. (2025c). Total natural resources rents (% of GDP). Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.TOTL.RT.ZS?view=chart (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- World Economic Forum. (2023). Global risks report 2023 (18th ed.). World Economic Forum. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-report-2023/ (accessed on 2 May 2025).

- Xu, Y., Wu, X., Adam, N. A., Sultan, M. S., & Sumaira, A. A. (2025). Decarbonizing growth: Nuclear energy, green investments, and CO2 emissions in BRICS economies. Annals of Nuclear Energy, 224, 111746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Category of Countries | Country | Green Investment (Score 0–100), GrFn | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Developed countries | Denmark | 71.00 | 72.77 | 72.77 | 72.77 |

| Finland | 55.01 | 56.68 | 56.68 | 56.68 | |

| Germany | 68.50 | 69.67 | 69.67 | 69.67 | |

| South Korea | 70.41 | 72.59 | 73.28 | 73.97 | |

| United States | 63.47 | 65.14 | 65.14 | 65.14 | |

| Developing countries | Armenia | 36.07 | 43.00 | 41.86 | 40.72 |

| China | 56.19 | 59.06 | 59.65 | 59.19 | |

| Malaysia | 53.68 | 58.99 | 63.27 | 65.33 | |

| Russia | 68.26 | 72.07 | 71.13 | 71.13 | |

| Slovakia | 65.76 | 66.21 | 65.07 | 69.79 | |

| Category of Countries | Country | Total Natural Resources Rents (% of GDP) | GDP per Unit of Energy Use (Constant 2021 PPP USD per kg of Oil Equivalent) | Carbon Intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP USD of GDP) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EvCs1 | EvCs2 | EvCs3 | |||||||||||

| 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Developed countries | Denmark | 0.59 | 0.45 | 0.16 | 0.34 | 24.14 | 24.72 | 25.24 | 26.72 | 0.08 | 0.07 | 0.07 | 0.06 |

| Finland | 0.56 | 0.37 | 0.29 | 0.45 | 9.45 | 9.66 | 9.47 | 10.04 | 0.14 | 0.13 | 0.11 | 0.10 | |

| Germany | 0.08 | 0.09 | 0.08 | 0.08 | 17.63 | 18.02 | 18.04 | 19.44 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.13 | 0.11 | |

| South Korea | 0.05 | 0.12 | 0.11 | 0.05 | 8.76 | 8.92 | 8.78 | 9.20 | 0.27 | 0.25 | 0.23 | 0.22 | |

| United States | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.33 | 1.28 | 10.32 | 10.97 | 11.07 | 11.17 | 0.22 | 0.20 | 0.20 | 0.19 | |

| Developing countries | Armenia | 1.10 | 2.20 | 2.42 | 7.05 | 13.94 | 12.21 | 12.52 | 13.27 | 0.13 | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.13 |

| China | 1.43 | 1.27 | 0.86 | 1.71 | 7.83 | 7.77 | 7.91 | 7.99 | 0.45 | 0.43 | 0.41 | 0.41 | |

| Malaysia | 7.33 | 6.20 | 4.54 | 6.92 | 10.87 | 10.73 | 10.68 | 11.19 | 0.24 | 0.25 | 0.25 | 0.25 | |

| Russia | 14.47 | 12.21 | 7.59 | 18.51 | 7.49 | 7.33 | 6.92 | 6.94 | 0.35 | 0.34 | 0.36 | 0.35 | |

| Slovakia | 0.29 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 0.23 | 11.89 | 11.94 | 11.60 | 12.51 | 0.17 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.16 | |

| Category of Countries | Country | Access to and Affordability of Justice | Timeliness of Administrative Proceedings | Expropriations Are Lawful and Adequately Compensated | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gvn1 | Gvn2 | Gvn3 | |||||||||||

| 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | 2019 | 2022 | 2023 | 2024 | ||

| Developed countries | Denmark | 0.76 | 0.78 | 0.78 | 0.79 | 0.88 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 0.90 | 0.87 | 0.85 | 0.87 |

| Finland | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.79 | |

| Germany | 0.79 | 0.77 | 0.76 | 0.75 | 0.83 | 0.85 | 0.80 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.91 | |

| South Korea | 0.69 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.80 | 0.81 | 0.78 | 0.75 | 0.76 | 0.77 | |

| United States | 0.44 | 0.45 | 0.45 | 0.48 | 0.56 | 0.60 | 0.58 | 0.55 | 0.70 | 0.71 | 0.71 | 0.71 | |

| Developing countries | Armenia | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. | n.a. |

| China | 0.61 | 0.65 | 0.66 | 0.68 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.60 | 0.64 | 0.39 | 0.35 | 0.36 | 0.38 | |

| Malaysia | 0.58 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.56 | 0.55 | 0.55 | 0.49 | 0.49 | 0.50 | 0.50 | |

| Russia | 0.60 | 0.61 | 0.62 | 0.63 | 0.61 | 0.58 | 0.57 | 0.59 | 0.38 | 0.36 | 0.36 | 0.35 | |

| Slovakia | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.57 | 0.62 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.68 | 0.66 | 0.67 | 0.65 | |

| Regression Statistics | Developed Countries | Developing Countries | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model for EvCs1 | Model for EvCs2 | Model for EvCs3 | Model for EvCs1 | Model for EvCs2 | Model for EvCs3 | ||

| Multiple R | 0.3611 | 0.4826 | 0.1414 | 0.3078 | 0.5488 | 0.4397 | |

| R-square | 0.1304 | 0.2329 | 0.0200 | 0.0947 | 0.3012 | 0.1934 | |

| Standard error | 0.3024 | 6.0158 | 0.0647 | 5.1085 | 2.0235 | 0.1009 | |

| Significance F | 0.1861 | 0.0685 | 0.6151 | 0.2644 | 0.0341 | 0.10097 | |

| Coefficients | Y-intercept | 1.5149 | −19.1298 | 0.0521 | −4.2401 | 17.3772 | −0.0045 |

| GrFn | −0.0177 | 0.5021 | 0.0014 | 0.1498 | −0.1204 | 0.0045 | |

| Regression statistics | Model for GrFn | ||||||

| Multiple R | 0.3053 | 0.8943 | |||||

| R-square | 0.0932 | 0.7998 | |||||

| Standard error | 6.8341 | 5.3663 | |||||

| Significance F | 0.7716 | 0.0004 | |||||

| Coefficients | Y-intercept | 55.6649 | 42.1262 | ||||

| Gvn1 | 14.1786 | 3.4105 | |||||

| Gvn2 | 1.7871 | 26.5479 | |||||

| Gvn3 | 0.9720 | 12.3471 | |||||

| Cross-Correlation | Green Investment (Score 0–100) | Total Natural Resources Rents (% of GDP) | GDP per Unit of Energy Use (Constant 2021 PPP USD per kg of Oil Equivalent) | Carbon Intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP USD of GDP) | Access to and Affordability of Justice (Worst 0–1 Best) | Timeliness of Administrative Proceedings (Worst 0–1 Best) | Expropriations Are Lawful and Adequately Compensated (Worst 0–1 Best) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green investment (score 0–100) | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total natural resources rents (% of GDP) | −0.36 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| GDP per unit of energy use (constant 2021 PPP USD per kg of oil equivalent) | 0.48 | −0.14 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Carbon intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP USD of GDP) | 0.14 | 0.03 | −0.76 | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Access to and affordability of justice (worst 0–1 best) | 0.31 | −0.61 | 0.53 | −0.57 | 1.00 | - | - |

| Timeliness of administrative proceedings (worst 0–1 best) | 0.30 | −0.64 | 0.48 | −0.53 | 0.97 | 1.00 | - |

| Expropriations are lawful and adequately compensated (worst 0–1 best) | 0.25 | −0.49 | 0.73 | −0.72 | 0.83 | 0.72 | 1.00 |

| Cross-Correlation | Green Investment (Score 0–100) | Total Natural Resources Rents (% of GDP) | GDP per Unit of Energy Use (Constant 2021 PPP USD per kg of Oil Equivalent) | Carbon Intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP USD of GDP) | Access to and Affordability of Justice (Worst 0–1 Best) | Timeliness of Administrative Proceedings (Worst 0–1 Best) | Expropriations Are Lawful and Adequately Compensated (Worst 0–1 Best) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green investment (score 0–100) | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Total natural resources rents (% of GDP) | 0.31 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - | - |

| GDP per unit of energy use (constant 2021 PPP USD per kg of oil equivalent) | −0.55 | −0.45 | 1.00 | - | - | - | - |

| Carbon intensity of GDP (kg CO2e per 2021 PPP USD of GDP) | 0.44 | 0.24 | −0.94 | 1.00 | - | - | - |

| Access to and affordability of justice (worst 0–1 best) | 0.88 | 0.09 | −0.64 | 0.67 | 1.00 | - | - |

| Timeliness of administrative proceedings (worst 0–1 best) | 0.88 | 0.13 | −0.65 | 0.68 | 1.00 | 1.00 | - |

| Expropriations are lawful and adequately compensated (worst 0–1 best) | 0.80 | −0.17 | −0.10 | 0.12 | 0.81 | 0.79 | 1.00 |

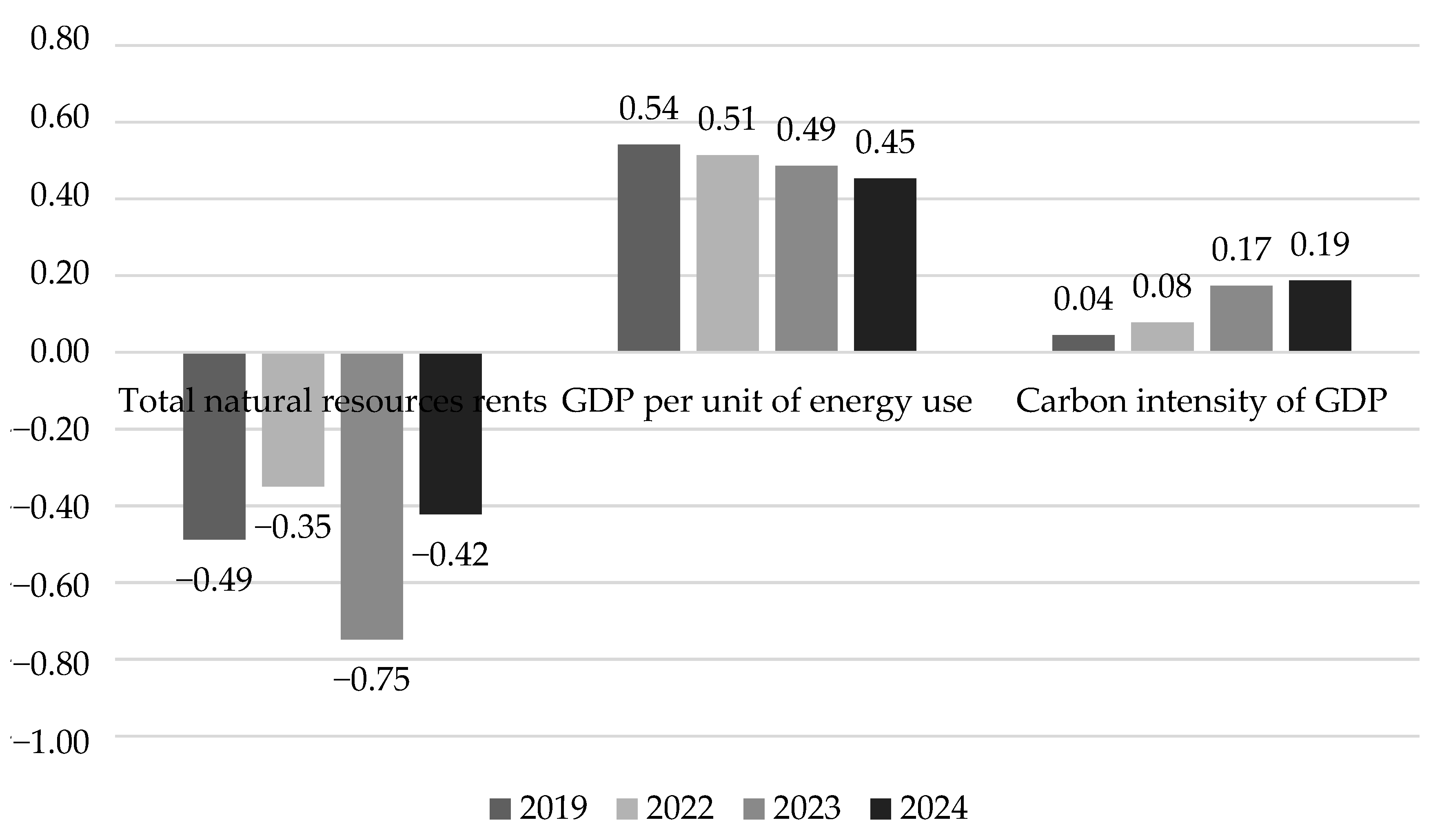

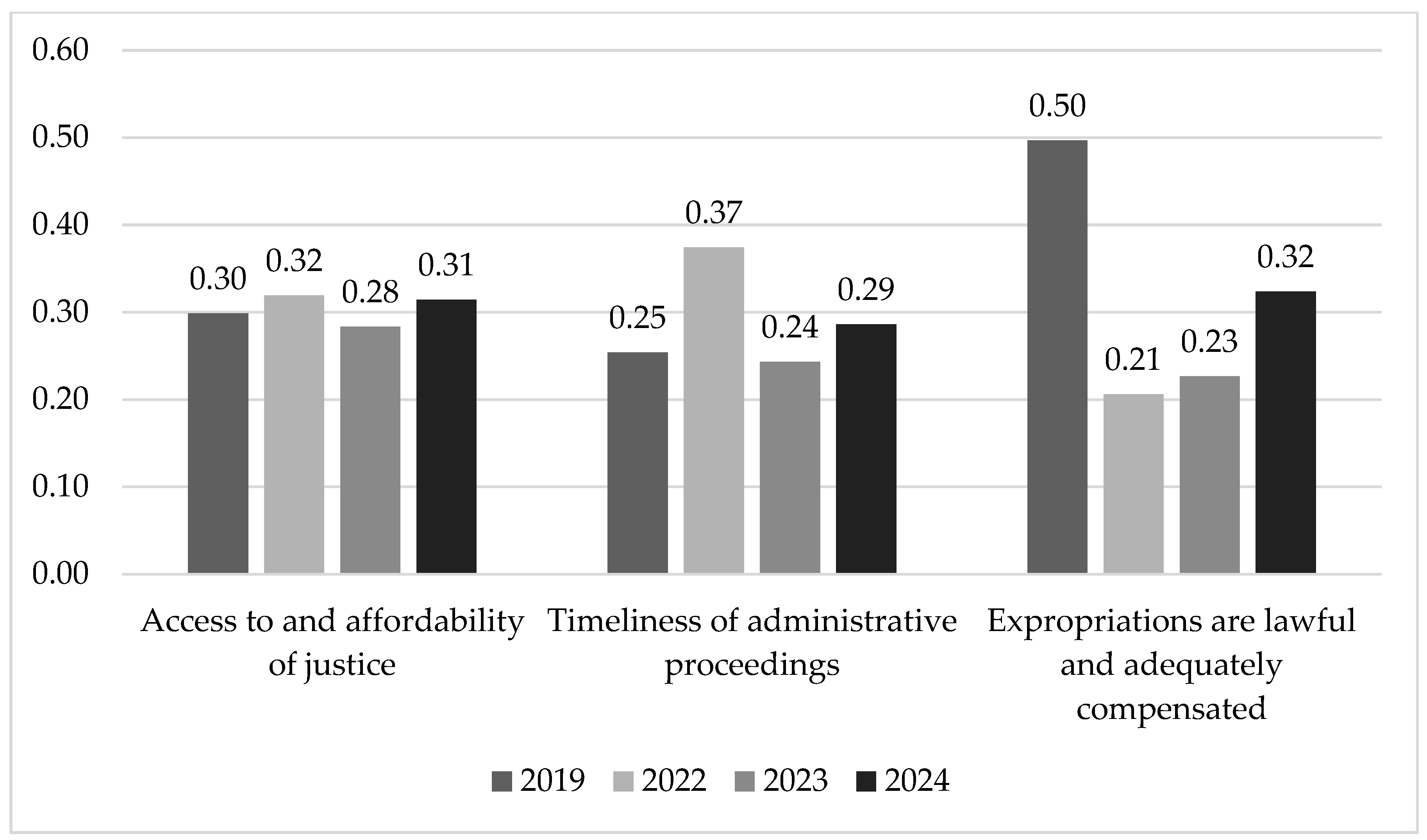

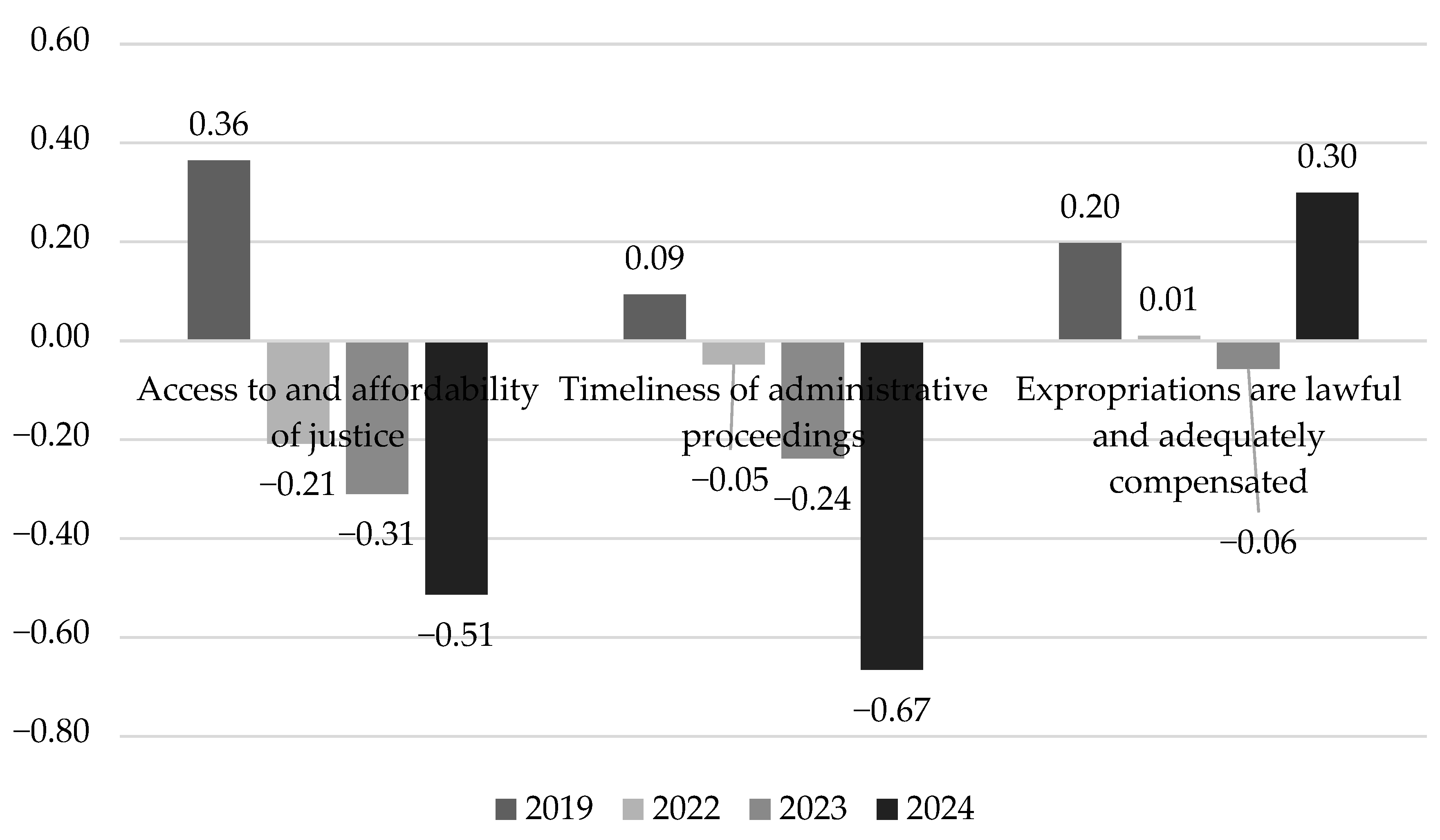

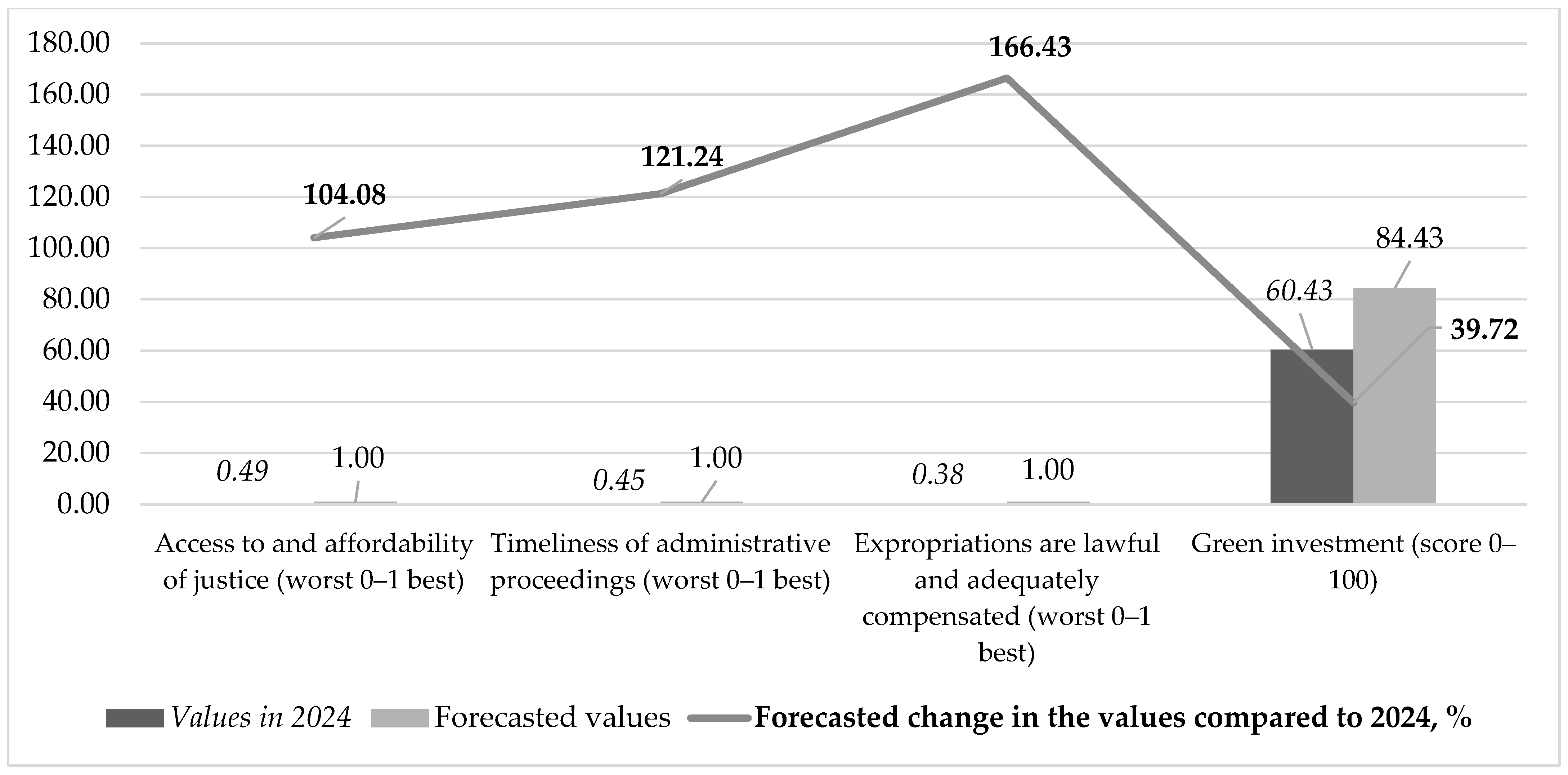

| Research Object | Description in the Past Literature | In Developed Countries | In Developing Countries | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection with Green Investment (Regression) | Change in the Connection Due to Instability (Correlation) | Connection with Green Investment (Regression) | Change in the Connection Due to Instability (Correlation) | |||

| Consequences for the environmental costs of GDP (environmental risks of the economy) | Natural resources rent | Al-Rawashdeh et al. (2025) | Positive (−0.0177) | Almost unchangeable (−0.49 in 2019; −0.42 in 2024) | Negative (0.1498) | Almost unchangeable (0.36 in 2019; −0.51 in 2024) |

| Energy intensity | Azimi et al. (2025) | Positive (0.5021) | Deterioration (0.54 in 2019; 0.45 in 2024) | Negative (−0.1204) | Almost unchangeable (0.09 in 2019; −0.67 in 2024) | |

| Carbon emissions | Lu et al. (2025) | The F-test was not passed | Almost unchangeable (0.04 in 2019; 0.19 in 2024) | Negative (0.0045) | Almost unchangeable (0.20 in 2019; 0.30 in 2024) | |

| Dependence on the factors of state regulation of green finance | Strength and financial accessibility of legal regulation of administrative disputes | H. Li et al. (2025) | The F-test was not passed | Almost unchangeable (0.30 in 2019; 0.31 in 2024) | Positive (3.4105) | Deterioration (0.46 in 2019; 0.18 in 2024) |

| Its timeliness | Susan and Pan (2024) | The F-test was not passed | Improvement (0.25 in 2019; 0.29 in 2024) | Positive (26.5479) | Deterioration (−0.67 in 2019; −0.48 in 2024) | |

| Protection of investors’ property rights | Z. Wang et al. (2025) | The F-test was not passed | Deterioration (0.50 in 2019; 0.32 in 2024) | Positive (12.3471) | Deterioration (0.43 in 2019; 0.40 in 2024) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Popkova, E.G.; Litvinova, T.N.; Petrenko, E.; Bogoviz, A.V. Regulating Green Finance and Managing Environmental Risks in the Conditions of Global Uncertainty. J. Risk Financial Manag. 2025, 18, 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100552

Popkova EG, Litvinova TN, Petrenko E, Bogoviz AV. Regulating Green Finance and Managing Environmental Risks in the Conditions of Global Uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Financial Management. 2025; 18(10):552. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100552

Chicago/Turabian StylePopkova, Elena G., Tatiana N. Litvinova, Elena Petrenko, and Aleksei V. Bogoviz. 2025. "Regulating Green Finance and Managing Environmental Risks in the Conditions of Global Uncertainty" Journal of Risk and Financial Management 18, no. 10: 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100552

APA StylePopkova, E. G., Litvinova, T. N., Petrenko, E., & Bogoviz, A. V. (2025). Regulating Green Finance and Managing Environmental Risks in the Conditions of Global Uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Financial Management, 18(10), 552. https://doi.org/10.3390/jrfm18100552